Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The Lilliput Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

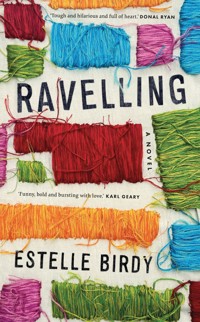

SET IN DUBLIN'S LIBERTIES, Estelle Birdy's explosively original debut Ravelling channels the energies and agonies of young men let loose in the city, their city, navigating the tumultuous trajectory of youth and young manhood, where they balance their hopes with the harsh realities of their present. Hurtling between friendships, feuds, drug-deals, family and brushes with the law, this is modern Dublin as never before portrayed. Ravelling follows Deano, a weed-smoking hurling star, living with his aunt in an about-to-be-demolished flat; Hamza, a Pakistani Muslim atheist and precocious academic, who sells his ADHD drugs to the kids in a private school; Oisín, empathetic and iron-willed, who has begun to see his dead brother at the end of his bed; Congolese nature lover, Benit, who just wants to relax and hurl with the lads; Karl, a maybe-gay fashionista, dreaming of something better while immersing himself in his art. Bound by friendship, place and the memories of those who've died too soon, these young men grapple with race, class, sex, parties, poverty, violence and Garda harassment, all while wondering what it means to be a man in twenty-first century Ireland. 'Ravelling masterfully evokes the fragility and beauty of human relationships. It's funny, bold and bursting with love. There's no moral here, just an ode to community, a burning sense of youth and a plea for a society pushed to the margins.' KARL GEARY 'A glorious novel, tough and hilarious and full of heart. What a writer! Every line sings from the page.' DONAL RYAN 'Written in fluent, truthful prose, with humour and empathy abounding.' SEBASTIAN BARRY 'A brilliantly profane, hilarious ride through the Liberties … Ravelling lays a sparkling new Dublin over the old. A revelation.' LAUREN MACKENZIE

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 581

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

RAVELLING

RAVELLING

Estelle Birdy

THE LILLIPUT PRESS DUBLIN

First published 2024 by

THE LILLIPUT PRESS

62–63 Sitric Road, Arbour Hill

Dublin 7, Ireland

www.lilliputpress.ie

Copyright © 2024 Estelle Birdy

Paperback ISBN 978 184351 8648

eISBN 978 184351 9027

Quotation from 'The Rebel's Silhouette' by Faiz Ahmed Faiz, translated by Agha Shahid Ali, 1991 by permission of University of Massachusetts Press.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means without the prior permission of the publisher.

A CIP record for this title is available from The British Library.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

The Lilliput Press gratefully acknowledges the financial support of the Arts Council/An Chomhairle Ealaíon.

Set in 11pt on 14pt Minion Pro by Compuscript Printed in Sweden by ScandBook

For Dublin and her Dubs, including my own lovely four.

Autumn

1

DEANO

Normal funeral. All guilt and umbrellas. Lashing, bit cold for early September.

Deano lanks against the church wall, waiting. Gives the chin to the women sharing brollies just inside the railings. Sadie from the flats shop, with the big orange head on her, Rita from the dry-cleaners, groomed within an inch of her life, Doreen from the Tenters Residents Association, who has managed, for once, to leave that weepy-eyed bichon frise out of her arms. The mental trio turns at the sight of Hamza and Benit coming through the gate to line up beside Deano. Bout time.

A string of frayed yellow-and-white bunting – some novena or saint’s bones tour – flaps over their heads, dripping massive raindrops that roll down the back of Deano’s stillpeeling neck. Stings like fuck. There’s no point in him even trying that tanning craic: the freckles are never gonna join up. The aul ones mutter to each other, looking over at himself and the lads. Hamza, rubbing that full black beard of his, grins and mumbles something about Allah in the women’s direction. Benit digs his hands deep into his jeans and whispers:

– If you go full Allahu Akbar on them like that time on the bus, I’m leaving, yeah? Why we standing in the rain? Let’s go in.

– Nah, we’ll wait out here for the boys. And those aul ones will be more worried about you than me, gangsta-man.

– Yeah, did you have to wear that do-rag, Benit? Deano says.

– Yeah I did have to wear the do-rag, Benit says, hopping from one foot to the other. Black. For the funeral. Gotta keep the hair right, fam. It’s raining like. ’Mon, can we not go in?

– Nah, just stay here. See them aul ones? They know the story. You stand outside till other people come.

– It’s Baltic. There’s people inside already. I can see them.

– Fuck’s sake Benit would you ever quit whinging? Deano says. Boys said meet outside. They’re on their way.

– But it’s raining, fam!

– Sherrup faggot, Hamza says, and Deano smiles just a little.

The aul ones hear that alright. Muttering, shaking their heads and gathering closer, their backs and umbrellas forming a shield.

– There were loads at my grandad’s funeral, Benit says. Pouring out the door they were. Had to get speakers put up outside. Mobbed, cos of his anti-drugs stuff, back in the day.

– Your famous white grandad, Hamza says. No one’s coming to this one at all. Jack’s just another dead junkie. He was trying, you know? Coming to mosque and all.

– Like the mosque was what Jack needed, Deano says.

– People were helping him like. He came on a hike up the mountains with us. Those aul ones are just here for the gossip. Probably didn’t even know him.

– Come on, leave them be, Benit says. Look, here’s the boys now.

Down the street, Oisín – blond and tanned – is chatting away with roundy Karlo, fish-belly white and always smiling. Even today.

– Sup, Benit says.

– Alright?

– Going full Kendrick with the do-rag, Benit? Oisín says.

– Am a real nigga, not a wannabe.

– Would you ever quit, Benit? Oisín says, looking over at the women.

– Nigga’s gonna speak if a nigga’s gonna speak. See you’re doing your bit to raise the bar there, as usual, Karl. Nice.

– Yeah, d’yeh like it, Benit? I’ve me Givinchy under the jacket, Karl says. Bitta respect for the man in the box, know what I mean? See me new Louboutins?

He turns his feet from side to side, showing off the rubbery spikes on the tops of his shoes.

– Yeah, the homeless lad’ll appreciate you wearing a five-hundred-quid top to his funeral, Oisín says.

Hamza frowns.

– You really spend five hundred quid on that top, man?

Seriously?

– Nah, only three. Sale price.

– You’re working in Penneys, and you’re spending everything you get on fucking labels?

– Yeah, and I look fresh, Karl says, flipping up his collar.

– In fairness, he does. Respect, Benit says, fist-bumping Karl.

The rain eases a bit, as two black limos glide up to the gates. The huddle perks up. Rita and Sadie suddenly look all mournful, blessing themselves like they’re on the telly. Sadie drops her chins to her chest but keeps her eyes fixed on the limos. Everyone’s getting edgy before the driver of the first one gets out and opens the back door. One stick-thin, black-stockinged leg comes out, then another.

– Those are some heels, Oisín says.

The driver offers his arm and a leather-gloved hand grabs it. It’s not that cold like. A big black hat with a veil appears. Straightening herself as the driver holds an umbrella over her, the woman lifts the veil. Fly shades. She pops a foot-long cigarette holder into her mouth and waggles it up and down between scarlet lips. The driver, looking confused, pats his pockets.

– Fucking hell, boys, Karl whispers. This is the best.

– His mam, is it? Benit says.

– Nah, Sandra’s his mam, says Oisín. The big one. Lives down the road.

– No, Hamza says. Sandra’s his foster mum.

– Who else would it be in anyway? Has to be his ma, says Karl, patting himself.

Jaze, he loves that jacket.

– Can we’ve a bitta respect for Jack, boys? That’s why we’re here, Deano says.

He heads over to the limo, pulls out the Zippo June got him for the birthday, and lights the woman’s smoke. Check her out.

– You his mam? he asks.

– I am, yes, she says, smiling broadly.

Those lips look like they could explode any second and she’s fooling no one with that fake posh accent. Yeh can’t trust a Dub who doesn’t wanna be a Dub, as Deano’s da used to say.

All the flats know about Jack’s real mam. The parties in the flat with the kids left out on the green, nothing but a Formica table and a soaking armchair for shelter. The batterings, the social workers and the constant garda visits. This yoke with the fancy hat didn’t even have the excuse of being a junkie like Deano’s ma.

Jack told them his ma didn’t have a pot to piss in over there in Birmingham. That’s why she could never help him out or give him a place to stay off the street, he said.

So who the fuck was paying for all of this gear?

A young one gets out of the second car, pulling at the bottom of her black elasticky dress. No hat, about their age, nice pair of tits, serious arse, ironed scarlet hair. She looks over at the lads and the waterworks start. Jack’s mam teeters away, puts her arm around her. The young one shrugs her off. The aul one hisses something into the girl’s ear, then spits onto a wad of kitchen towel, fished out of the sequinned handbag dangling from her wrist, and makes to scrub the girl’s face. She lashes out, slapping the woman’s hand away.

– Me make-up, Mam!

She looks the business, this girl. Orange, obviously. Tarantula eyelashes, and her face is a bit patchy after the kitchen towel and spit. But still.

Deano strolls back to the lads, glowering.

– Not to be trusted, he says out of the corner of his mouth.

The aul one especially. The younger one but …

– Sister? Karl asks.

– Come on, boys, let’s go in, Hamza says, smirking at Benit. Why we standing out here? Sure it’s lashing.

*

Inside, the guest of honour is already there, lying in a wicker coffin on a trolley near the altar. There’s a table with a framed photo of Jack, smiling and looking a lot fuller in the face than Deano remembers. A wreath of blood-red roses lies at the foot of the trolley.

The old priest had notions, was dead proud of the fact that he got some Polish artist who did gruesome paintings of life under the commies to do the stations of the cross that line the walls. One of the green electric candles that light the paintings is flickering on and off, making Jesus falling for the third time look like a scene from Insidious.

– Fuck, they’ve Jack like a basket a chips in Zaytoon, Deano whispers into Oisín’s ear. There’ll be marks and all on his neck, don’t wanna see that. Go up near the middle there.

– The coffin’s not open, for fuck’s sake, Deano.

– I’m going up the front, Hamza says.

– That’s for family, Deano says.

– We are his family, Hamza says.

– There’s Sandra up there at the front, and the pair outside, Deano says. They’re family. We’re going middle.

– I’m not sitting beside no feds, fam, Benit says.

Community Garda Gerry and Sergeant Dwyer are staring into their laps, arms folded. Gerry’s all about building bridges. Dwyer’s a traditionalist, thinks a few digs out the back of Kevin Street is all these young fellas need. They’re already being given a wide berth by the rest of the small crowd: a few scrubbed-up homeless lads from around Camden Street, a clatter of women from the flats, and Sadie & Co.

Garda Gerry has been popping up round every bleedin corner, over the past few weeks, with his Mullingar chucklehead, talking like a turkey, trying to have the craic. He’s an embarrassment.

– Ah yeah, hadn’t seen them, definitely go further up than them, Deano says, pushing past the others to lead them up to a pew a few rows behind Sandra and her younger foster kids.

Hamza turns to grin at the guards, who stare back, stonyfaced.

– There’s always guards at funerals, Deano says. Hamza laughs.

– No there’s not, you mad rat. Just the funerals you go to.

Right enough, there’d been swarms of guards at Deano’s da’s funeral. Along with most of the flats. Shot in the street in front of Deano. They’d been walking home from hurling. His da wasn’t even caught up in anything.

The click of heels on the tiled floor and the noisy sniffling draws everyone’s attention to the mother and daughter, as they carry in a plastic-flowered ‘SON’ wreath. The mother plops it on top of the roses. Pressing it down with the pointed toe of her shoe for good measure. Loadsa flapping and sighing and the pair take their seats in the first pew, across from Sandra and the kids.

The undertaker, a lanky grey man, silently appears at the end of the lads’ pew, crouching down beside Deano.

– Excuse me, are you friends or family?

– Neither, says Hamza, leaning across.

– We’re friends, Deano says, digging Hamza in the ribs.

– The family, Marian and Candy, have asked us to ask you young men to help carry the coffin after the service.

– No problem, mate, Deano says. Give us a shout when you need us.

– Candy? Hamza says, when the undertaker’s out of earshot. Fucking Candy?

The priest starts proceedings.

– One of yours Benit, Hamza says, biting his lip. Can’t understand a word he’s saying.

– Says the Paki. Sounds Nigerian, not one of ours, fam.

The priest raises his voice a bit and pulls the microphone closer, as the sniffling from the first pew turns to sobbing.

– I had the privilege of meeting Jack on several occasions in recent times. He was a young man with a big heart. But life took its toll, as for so many, and he was no longer able to cope. This is a time to pull closer …

The wailing grows louder, bouncing off the walls, drowning out the poor priest. Sadie’s crowd sit taller in their seats, lamenting not having come further up the church, probably. Outta nowhere, at the front, Candy’s up out of her seat.

– Don’t leave me, Jack!

She lashes herself over the coffin, sobbing.

– What the fuck? Karl says, under his breath.

The priest pauses for a second, takes a couple of steps forward, thinks better of it, and retreats back to his mic. He’s mumbling something about the community of God but no one’s listening now. All eyes on the girl. The mother stands up, shrieks and clutches her chest. For the love of fuck. Candy, thrown by the competition, by the looks of it, hitches her dress up even further and paces up and down alongside the coffin, like a cat about to drop kittens. The mam gets louder, shriller.

– That stained glass won’t last much longer if this keeps up, Hamza says.

The young one stops and starts fumbling with one of the coffin’s leather straps, struggling with the buckle. And just like that, she throws the leg over, giving everyone an unmissable flash of white knicker.

One of her hold-ups snags on the wicker basket. It tilts and slides a little to the right. The mam stops her screeching. For a bit, the creak of the coffin, the rattle of the metal trolley and the thud of heavy platform shoe on stone – as she hops about with one leg caught on the wicker – make this kinda music beat that echoes all over. And then she does it. She twists and turns and she’s suddenly lying face-down on top of the coffin. The priest looks frozen to the spot. There’s gasps and screams. The trolley shakes. The coffin slides a bit more, then does a nearly ninety-degree spin and starts to wobble, Candy clinging to it.

The lads shoot out of their seats. Benit launches himself at the base of the trolley, gripping the legs. Deano and Hamza grab the girl’s arms. Others slide the coffin back into place, just as the breathless undertakers arrive. Without so much as a glance in the direction of the mother and daughter, the grey men tighten the coffin straps.

– Sit down and don’t fucken budge, Deano says, through clenched teeth, into Candy’s face.

One’s as bad as the other. The mother glares at the daughter, dry-eyed.

Sandra, catching Deano’s eye, mouths, ‘Thank you’, and gets back to fidgeting with her soggy tissue. Her kids gawk at the two women across the aisle, then whisper amongst themselves. The priest, still looking stunned, half-smiles at Benit when he says, brushing himself down:

– Right, you get on with it there, Father.

The two Guards sit back down and Gerry, catching Deano’s glance as he gets back to his pew, gives him a good-man-there-now garda blink. Back in their seats, the five of them look straight ahead. Jaysus. What can yeh say?

The priest fiddles with the mic and backtracks.

– I met Jack on many occasions in recent times. A young man with a big heart. Life broke him.

The air is heavy with the smell of burning wax and some kind of perfume that’d make you puke. At communion time, the lads stay where they are. A woman on the balcony starts singing ‘In the Arms of the Angel’ in an opera voice and someone beside Deano sniffles. Deano doesn’t look but Karl’s shifting about like he needs a shite, and then he coughs. Benit starts whispering to Hamza again:

– Your folks know you’re here?

– No.

– They think you’re in school? School’ll be looking for a note. You gonna tell your folks you were in a church, fam?

– We’re Pakis, not aliens like. We’re okay with churches. And, you know, going to our mates’ funerals. What are you on about anyway, I’ve had to sit here through all of your communion trainings and shit?

– Forgot you were here.

– Nice. Yeah, and the funerals. Yep, all the funerals.

– There’s loads of non-Muslims in Pakistan anyway.

– No way fam. You’re not all Muslamics?

– There’s about twenty billion non-Muslamics lurking in Punjab. Christians, they get everywhere.

– Boys, keep it down, yeah? Deano says.

– Like the rest of this crowd? Hamza says, eyebrows raised. But he shuts up.

The priest, looking shook, struggles through the rest, waving the big gold incense thing a bit too fast, making Deano sneeze. Outside, they lift Jack onto the back of a horse-drawn hearse. The black horses stand quiet, as Karl, Oisín and Hamza rub their muzzles, murmuring, running their fingers through the bridle plumes. They’re real horsey people, bought a pony between them when they were fourteen. Deano loved that, sitting around the stables, out the back of Thomas Street. The lads mucking about. Karl has a way with horses – in the blood. Chose them a good one up in Smithfield. Sold her on to the lads with the carriages up at Guinness’s.

At the burial, the priest announces that the family wants to welcome all the mourners to Sheedy’s for something to eat afterwards.

– Jesus, Sheedy’s! Who’s on for getting shivved before we can get the sambos into us? Oisín says. We all in so?

Not one of them has ever actually been into Sheedy’s. They’ve just heard all the stories, and everyone knows the kind of scald that smokes outside the kip. Karl’s cousin had the shit kicked out of him in there by Wino Nestor. That was the month after the cousin got out of the Joy for the second time, after robbing a picture out of a house in Ballsbridge. Deano heard they were cleaning the walls in Sheedy’s for weeks after. Had to paint the place. Only the really bad bits but.

*

It’s early afternoon when they get to the pub on Cork Street. Apart from the guards, looks like everyone from the church is here. Even the priest’s made it. Sitting alone at the bar, head in hands, nursing a whiskey. Sadie and her crowd, with the women from the flats and Sandra (minus the kids), have formed a big group in one corner. Oisín’s mental next-door neighbour, Pearl, is stuck in another corner, looking like someone stood her up against a radiator and she melted. So, this is where she disappears to every morning. A row of small stools, propped against each other at jaunty angles, forms a barrier to one of the mezzanine areas. A scrawled sign stuck to the handrail announces ‘Resurved Funarel’.

– I’m bursting for a piss, Oisín says.

– Follow yer nose there for the jacks, Deano says.

On his way, Oisín nearly face-plants when his foot gets caught in the pulled threads, like mantraps, that are all over the scratchy mustard-and-red carpet. Jack’s mam, hatless now, jetblack hair scraped into a bun that leaves her eyes slitty, makes a beeline for them as she comes out from what smells like the pub’s kitchen.

– Boys! Men! she says with a wink. They’re making us up baskets of chips and chicken nuggets first. There’s punch on the way. Well, sangria really. Keep the summer going, I always say. You’d like that, wouldn’t yiz? We’re going to lay everything out up there, we’ve got girls coming in to serve, and we’re just going to keep it coming, all day and all night. Give Jack a great send-off.

She dabs her eyes with a Santy-covered paper napkin. No one says a word.

– I’m Marian, she says, offering her hand, the chips in her sparkling nail-polish showing the grime underneath.

They each give their names and no more. Then stand looking at her again.

– So, how did you all know Jack? she asks.

Fucker doesn’t give a shite.

– Met him when he was begging on Camden Street. We’re in Colmcille’s. We’d see him at lunchtime, Deano says.

– We’d go for lunch with him sometimes, Hamza says, playing nice.

– You’re all still at school? I can’t believe that, and the size of yiz, she says, smiling. Leaving Cert, I suppose, with you being so big?

– Yeah, Deano says, not giving her an inch.

– So, it’s a big year for you boys, then? Very important.

– Yeah, we’ll take it very seriously.

She bristles, then pastes the smile back on her face.

– Well men, eat when the food comes and drink up, she says, waving her hand towards the mezzanine as she glides back towards the kitchen, reaching up to give Oisín’s shoulder a quick squeeze as he passes.

– Where’s Candy, I wonder? Benit says.

– Probably back there in the kitchen, Karl says.

– Would yeh? Oisín asks.

– Fuck off, no! Deano says. The state of her. Would have, obviously. But she’s fucken tapped.

– I would. She’s still a ride, Oisín says. Looper or not.

– Peng ting, Benit says, eyes closed, nodding.

– Peng ting! She’s fucking manky, Deano says. She was just riding her brother’s coffin for fuck’s sake! You don’t even get with white girls, Benit. What are yeh on about?

– Still recognize a sweet one, fam, no matter how devoted I am to the sisters, Benit says, blowing a kiss into the air. Bunda too, innit?

– Oh yeah? Deano says. I’ll be watching you and Christina, from now on.

– That’s rotten fam, Benit says, shaking his head. You know Christina’s the queen, fam. And also my sister.

– And also a dyke, Karl says, helpfully.

– Yeah, cos only dykes don’t fuck their brothers right, Karl? Oisín says.

– She’s his white sister though, she’s not even related to him, Hamza says. Not really. If they wanted to get it on, there’s nothing stopping them.

– I only said that Candy’s a peng ting and youse are all about riding sisters. Paedos.

– And I only said that Candy’s fucken grim for riding her brother’s coffin. In front of a whole church-load a people. Simples.

– Would you though, Karl? And you a man of style and taste, Benit says.

– Nah.

– See? Cos she’s a coffin-shagging weirdo, says Deano.

– Something like that, yeah, Karl says, his face going pink.

– Yeah look, we get a drink while we’re waiting for this sangria gear?

The Shake’n’Vac scattered earlier – for the funeral, you know yourself – only barely masks the bang of stale drink, piss and puke, but it’s enough to set off Deano’s sneezing again as they head to the bar.

– No drink for me. Mum’ll smell it off me the minute I get home, Hamza says. I’ll just have a 7up please.

The massive barman tuts, rolls his eyes and slides the 7up along the bar. Fishing his ID out of his inside pocket, Deano studies the hulk’s thick arms, the sweat patches on his white shirt, and what looks like a blob of mayo on the loosened black tie that hangs over his belly. That fella’d fold yeh.

About to order, something at the back of the cavernous pub catches his eye: light on the oily, greying locks maybe. Up a few steps, in the plush area, Wino Nestor has an unobscured view of the front door. He’s nicely settled, with a few of his crew, a pint of blackcurrant in front of each of them. Wino sits back, folding his arms, staring down at Deano. Fuck this.

– Lads, I’ve no money on me, Deano says. Gonna head back to the gaff and get some. Some green at home too. I’ll bring it back.

– But we just got here, Karl says. He follows Deano’s gaze.

– Oh.

– Who’s that? Hamza says. Oh. Ah no, here, you’re not leaving because of him. No fucking way. It’s our mate’s funeral. He doesn’t own the place.

– I’ll be back. I’ve money at June’s. Just gonna get it, Deano says.

– Guess who’s not coming back, Hamza shouts after him as he bolts out the door.

*

Like a bleedin miracle, when he steps outside Sheedy’s door, the rain has dried up, the sun’s out. Starting to sweat, he stalks down the street, towards the flats. No fucken way, no fucken way, is he sitting trapped in there with Wino. And him smirking his greasy head off. The same way he did at Deano’s da’s funeral. Shaking Deano’s hand outside. Sorry for your trouble. Yeah, yeh are, yeh cunt. Sorry for me trouble.

Passing the building site, where the Donnelly Centre used to be, someone shouts.

– Alright Deano?

Callum, left school after his Junior Cert, has his own motor an all now.

– Yeah, grand. Just at a funeral. Yeh know Jack, the fella from Camden Street?

– Yeah, no. Who?

– Doesn’t matter. Homeless, he was. Me and the boys knew him. Killed himself.

– Ah fuck, sorry, yeah. Heard about him, I think, Callum says, pulling an invisible noose around his neck, his tongue lolling out the side of his mouth.

– That’s it, yeah. You still working the sites then? Good money? What’s this yiz’re building?

– Student accommodation. Fancy shit like. Yeah, it’s deadly so it is, the money. Still living with me ma. But I’ve got the Civic and a bird from Sandycove. Smokin, she is.

– Sandycove me hole. Dún Laoghaire is it? Does she actually know yeh? White stick, has she?

– Fuck off, Deano. You’re the one still going into that kip every day. Me, I’ve got it made. Deadly bird. Wads a cash. Going Crete in a couple of weeks. Send yeh a postcard.

– Whatever. I’m heading. Watch yeh don’t get that Sandycove one up the pole. You’ll have to get rid of yer Civic then, get one of them people carriers, Deano says, walking away.

– Not a hope, Deano, she won’t let me ride her, Callum shouts after him.

Zero chance of Callum ever being with a young one he’s not riding. Everyone knows he’s got two others pregnant already. Went to England, both of them. At least the Sandycove one’ll be able to get it done here now.

On the avenue, he passes under the eye of the Garda CCTV pole that towers over the entrance to the flats. Snitchy and Titch – what age are they, no more than fifteen – are leaning against the outside of the closed butcher’s, hands tucked into their tracksuits, feeling their balls. Deano tried that for about a month when he was that age, staunching around, hands in his cacks. Oisín asked him what the fuck was wrong with him going around like a prick, mauling his cock. So Deano quit doing it.

A few ten-year-olds on bikes and scooters are hovering around – the real distributors. As soon as Deano turns the corner of his block, out of sight of the CCTV pole, Snitchy is up his arse.

– Are yeh looking, Deano?

– Nah Snitchy, I’m grand.

– I can get yeh anything, Deano. K, Mandy, whatever.

Deano stands and takes Snitchy in. Deano’s strictly a naturals man these days: green, hash, mushrooms the odd time, nothing heavy. Pills now and again, but he’s mostly given that up. White man’s food, as Benit says. And here’s Snitchy, all five foot of him, offering him Dublin’s best. And Snitchy’ll get clipped in some filthy jacks of some scabby pub when he’s of no use or when he scopes the wrong bird or when he breaks up the wrong fight, like Deano’s da. And no one will give a shite, except Snitchy’s ma.

– Nah thanks, Snitchy. I’m grand, seriously.

Snitchy drops to a whisper and winks:

– Any other gear? Have some Canada Goose coming in.

Deano shakes his head, laughing.

– I’ve a couple a knives. Nothing that’ll get yeh in any trouble, know what I mean?

– I’m grand, Snitchy.

– OK Deano. Yeh know where I am, yeah? Yeh have me number?

– Yeah, I have yer number.

*

Deano climbs the stairs to the flat. It’s the only one not boarded up on this landing. They reckon they’re regenerating the flats. They’ve been reckoning that ever since Deano can remember. Most of the other blocks are knocked this ages, but nothing’s ever been built.

June used to say she was born and raised in these flats and she wanted her kids to grow up round here but they’ve been waiting so long she’s had to give in. She’ll look at other areas now, as long as she gets a house and a garden; she’s done her time in the flats and most of the decent people are gone already. Like her full-time job it is, getting herself moved up the list, hassling the Corpo. She’s down there every day nearly, talking to social workers and housing officers and whoever’ll listen. Says she’s ready to move out as soon as they offer her something proper.

Andrea, one of the twins born premature, has fucked-up lungs. The damp in the flat is killing her. June won’t move to a private place but. They’d lose their place on the list, and there’s no way she’s ending up with some HAP landlord fucking her over. Says her da would turn in his grave if she gave up on Corpo housing. Reckons they might have a house down in Crumlin. There’s no way Deano’s moving to Crumlin but. Fucking savage they are down there. He’s told her he’ll stay in a friend’s gaff till after the Leaving, if he has to. Oisín’s ma offered and Karl’s, but there’s no way he’s kipping in Karl’s with that cousin of his fucking around, getting the place raided. So Karl’s is out but maybe Oisín’s. Anyway, he’s not going Crumlin. No fucken way.

He lets himself into the flat. The familiar stink of bleach nearly knocks the head off him. June never quits with it, worse than anyone else in the flats, permanently at war with the black mould.

– Ah, hiya Deano, June says.

Ach, she should be collecting some of the kids at this hour.

– I’m not really back, Deano says, disappointed that he’s not going to have the place to himself.

– You left all your bedding on the sofa, this morning Deano. Put it away, will yeh?

– Yeah sorry. I was in a rush.

– Do it now love. So we can use the sofa this evening, yeah?

He pulls the sheet off, bundles up the duvet and pillow and shoves it all in the box in the bedroom, where all five of June and Robbie’s kids sleep.

– The kids are at sports day, she says, while she runs a duster round the door jamb. I ran into yer mam today, Deano. She was asking after you.

Deano freezes.

– She looks better, Deano. Says she’s trying to get on some course.

Deano blinks and blinks and blinks and keeps his eyes fixed on June’s face and doesn’t panic, doesn’t panic at all.

– Ah, hun, I’m just telling you. She does look a good bit better than the last time I saw her. Birmingham, that’s where she was. Cleared out of it to get sorted, she says. She’s maybe getting herself together?

He hasn’t met his mam in the three years since he’d been taken off her, when she couldn’t even get it together to get them a hostel for the night and June, his da’s sister, had taken him in.

– Where’d you meet her? Was it round here? he says, quietly, looking at the floor.

– No, down in Rathmines. I was walking back to the bus stop, and she just came round the corner.

Rathmines! That close.

– She living there now?

– Dunno. I didn’t want to bombard her with too many questions, Deano. She was friendly. Not angry with me, like before.

Every time it’s on the news that a woman’s body’s been found in a house or a flat or a bog hole in the mountains, Deano’s waiting for the knock at the door to tell him he needs to go and identify her. He doesn’t know which he’s spent more time thinking about or which’d be worse: her being dead and him having to hear what happened to her, or her being alive, living round here, and him having to see her scamming and stroking and being wasted as fuck, with not a tooth in her head.

– Deano, you alright? Should I not have said? She looks better. People can get better. Looks like she might be on methadone. The moon face, yeh know? She wasn’t always like this, Deano.

– Was she talking right?

June looks a bit sketch.

– A bit slurred, maybe? But she was all there. Better than I’ve seen her in years. She gave me her mobile number.

– I don’t want it.

– I’m not saying you want it. Just that I have it. You alright, love? You’re pale.

– Yeah, I’m grand. Can I go into the kids’ room for a liedown? I wanna go back to the funeral. Me belly’s hurting but. Just need a lie-down.

– The afters? Where is it?

– Sheedy’s.

– Ach Sheedy’s, Deano! You shouldn’t be round there. There’s all kinds in there. Are the rest of the fellas there? Is Oisín there?

– Yeah. Be grand, June. It’s a funeral. Jack’s ma, the real one, has it organized.

– Jesus Deano! Jack’s ma’s there! That’s about the size of it. If you go back, make sure you stick with the lads and come home early, right? Or I’ll be round for you. And don’t think I won’t. I’ll reef you out of it, do you hear me? Karl there, with what happened the cousin?

Deano feels his body get heavy. He needs to get horizontal, quick.

– Yeah look, I’ll have a lie-down. I’ll just go back for a while, right?

– I don’t want you drinking. I know you’re eighteen, but still. Not round there. Wino and his people drink in it. We don’t want to be around that lot. You don’t know who you’re talking to round there.

June doesn’t even drink, herself. Says it causes too much hassle. Robbie, her fella, drinks the odd time. Nothing serious.

Deano crawls onto the Spider-Man-covered bed. His belly hurts, and his throat’s still aching, and Jack’s dead and everything’s gone to shite.

*

When Deano gets back, there’s six or seven red-faced men and a couple of complete yackballs blocking the footpath outside Sheedy’s. They get the measure of him, once they see him under the lights, and clear a pathway. Deano’s happy, relaxed even. Half a joint of Gracie’s best and he’s flying. He shoves open the door and gets blasted by a wave of Celine Dion. The place is heaving. He pushes through the crowd, scanning over everyone’s heads. Shoals of crushed plastic cups, oozing the last of their dark pink liquid, are gathering along the skirting boards. Two young ones – not bad, not bad at all – try to squeeze through to the food area, one of them holding up a foil tray with a mountain of cocktail sausages and the other carrying a platter of limp, yellowy vol-au-vents. People grab fistfuls of sausages and look dubiously at the vol-au-vents as they pass.

– I wouldn’t mind giving you the sausage, love, a heavily pregnant fella says to one of the young ones.

– Any tickles? another shouts into the blondie one’s face and goes to poke her exposed armpit.

In the food area, the white paper tablecloths are soggy and torn. Jim Harrison, one of Wino’s heavies, is resting his fat arse onto the pink-stained corner of the food table. Legs akimbo, sniffing and rubbing his nose, he flashes a Joker grin at the young one in the red dress who’s wobbling between his feet.

– C’mere to me, pet, Jim says, as he pulls the girl tight against his belly. Turn round there a minute and I see what yer like from behind.

His mates let out a whoop as he flips the girl and thrusts himself against her arse, his tongue sticking out of the corner of his mouth. Where the fuck are the boys?

He finally finds Hamza, looking well settled into the snug beside an aul fella. He seems seriously mellow, and signals to Deano that he’s been puffing on an invisible pipe.

He pulls up a stool and squeezes into the corner beside Hamza, who’s now grinning up at the ceiling. He starts laughing and puts his phone down on the table for Deano to see him texting his mam. Pointless, since it’s all in jabber-jabber.

– Staying in Oisín’s tonight to go over maths, Hamza explains.

Ah, sure. Deano cops how much of a jocker Hamza’s in when, still laughing, he grabs a fistful of each of his own cheeks. To see can he spread the smile to his hands, he says.

– Smiling hands. Deadly, Deano says as he shoots a glance at the aul fella.

– What’s goin on? Is it a party or what? the old man says, eyes still fixed on the door of the snug.

– A funeral, Deano says.

– Whose funeral? I didn’t hear.

– Name was Jack Larkin, Hamza says, straightening himself.

– Jack Larkin, Jack Larkin. No brother of yours with a name like that. I say, no brother of yours, wha?

He cackles, sticking out his tongue, revealing few teeth.

– No brother of yours.

It’s hard to know what to do in these situations, at the best of times. He’s old, so Hamza’s never going to tell him to fuck off. Deano’d normally say something but Hamza’ll only be pissed off at him hassling an aul fella. And Hamza’s just so happy-looking. The man’s, like, crazy old. And he has three empty pint glasses in front of him and a half-full one in his hand. The stained glass and wooden walls of the snug move closer. Deano’s feeling that blunt a bit more now.

– No, he wasn’t my brother, Hamza says. He was my friend.

– Is that right? What age was he?

– Twenty only.

– Twenty? That’s a holy terror.

Now Hamza looks not so happy. And Deano definitely isn’t happy. Jack under all that soil. The door of the snug gets pulled open by a wiry barman, who’s joined the big lumpy one from earlier. He gives Hamza the once over but barely glances at Deano.

– You alright here, Marty? the barman says. Same again?

– I will, yeah.

– You? the barman says to Hamza, in a way that says he has no time for Hamza’s nonsense, whatever that nonsense might be, now or in the future.

– No, I’m okay, thanks, Hamza says.

– Deano? the barman says.

No point even thinking about why he knows his name.

– Nah, I’m grand, thanks.

The barman, lips pursed, picks up the glasses and leaves.

– Whoever heard of that? Refusing a pint? And none in front of you. Easy knowing you’re no Irishman. I say, easy knowing you’re no Irishman, the aul fella says to Hamza.

– I’ve no money.

– Cavan, is that where yer from? he says, finding himself very funny again.

Benit and Oisín tumble through the door of the snug, arms around each other.

– Jaysus, more of them. Youse are no brothers of the dead fella either, are yiz?

Benit and Oisín look at each other, then back at the Marty fella.

– What? they say, in unison.

– Sit down here a minute, the aul fella says. Shove up there you, yeh mad face-holding fella. Where are youse lads from?

– Carman’s Hall, Benit slurs.

Deano feels dreamy again, it’s coming in waves. Happy, sad, happy, sad. Suppose with the tan, Oisín does look a bit foreign.

– Carman’s Hall! the aul fella says. Would you ever get away ourrah that, you’re as black as me boot. Where are you really from?

– You mean where’s my family really from? Congo, is that what you’re looking for? Benit says, smiling.

– Born in Congo, made in the Liberties, Hamza says, delighted with himself.

The aul fella puts down his pint and looks into the distance, twiddling his thumbs. Is he going to lose the cool altogether? The lads side-eye each other. The aul fella clears his throat.

– I, eh, I spent a bit of time beyond in Congo meself. Long time ago now, long time. The best of people there. The worst of things done to them.

He lifts his pint to his lips, a slight shake in his hand.

– No way! Benit says. What were you there for?

– Jadotville, son. Jadotville. Have you heard tell of that place?

– Nah. In Congo?

– It is. Likasi, it’s called now.

– That’s in the other Congo.

– Ah, you’re Brazzaville so? Congo-Brazzaville. That’s the place. I went back there. After Jadotville. Cyprus too.

– Cyprus isn’t in Congo, Benit says.

– No, you’re not wrong there, son, it’s not. Yiz had a hard aul time of it over there in Congo. Both parts. Still not great, I believe.

– It’s better now, where I’m from, Benit says. I’ve been in Ireland a long time.

– Bet you saw things none of these lads in here’ll ever have to see, son.

Benit sticks out his bottom lip and frowns.

– Yiz never had it easy from the time of that bastard Belgian, did yiz? Not right what was done to your people, son. D’yiz want a pint? Come on, he says, pulling at the pocket of his trousers.

– Nah, you’re alright, Benit says, searching the faces of the others for some clue for what to do.

– Won’t hear of it, the aul fella says, dragging out bundles of crumpled notes. Yiz’ll share a pint with an aul soldier. Marty’s the name.

Deano sees the water pooling in the crags underneath his eyes, as he rubs his nose with the back of his hand.

– Yes, we’ll all have a pint, thank you, Hamza says.

*

This isn’t so bad. No one’s forgetting Jack like. Really they’re not. And them vol-au-vents with the curryish shit in them were actually alright. Deano stumbles on the way to the jukebox yoke. Those fucken mantraps! He drops down onto his hunkers. He’s gonna get this sorted for once and for all. What if some aul one got caught in this? He pulls and drags at the nylon threads but they just won’t break. This is a job for Benit and his bag of tools. Wherever he is.

A gap opens up in the legs surrounding him and there he is, still in his lair. Thought he was long gone. How could he miss him? Wino, giving him the stare, and him crouched on the floor.

He beckons him up. What are you supposed to do? No panic. He gets up – fuck the aul ones, they’ve survived this long sure – and walks over to the table. He’s towering above them. All the big men.

– Everything alright, Dean? Wino says.

– Yeah.

– Family alright? How’s June and the kids? Doing well? Nice. Bring up June. Wino’s just that kind of a fella.

Rat-faced, perma-tanned, the faded scar on his face where someone had cut him an extra-wide smile years before slightly hidden by his chin-length, oily hair. Is it a dye job? Probably not. He’d have to be getting locks of grey streaked through it in the hairdressers and even the fruitiest barbers wouldn’t do that for yeh.

– They’re fine, thanks. Wino’s eyes glitter.

– Good, good. That’s what I like to hear. Terrible about that young Larkin fella, wasn’t it? Least I could do, give him a good send-off. Go back a long way, meself and Marian. Business wise. Hear you were a friend of his. Shame, the way he went. That young one was awful upset in the church.

There’s a bit of a glint in his eye as he scans the room.

– Go and have some punch there, Dean, there’s more nosebag on the way. Saw you ran off earlier. Glad to see you’re back. Still at the – what’s this your sport is?

Deano clamps his jaw shut. Wino bangs the side of his head with the heel of his hand, like he’s trying to knock the word out of his brain.

– Hurling.

The two thicks on either side of Wino smirk. One of them makes a clicking sound with his tongue.

– Go on, Dean. Help yourself.

That’s him dismissed. Walking down the steps, Wino shouts after him,

– I’ll be seeing you, Dean.

*

There’s a massive sing-song going on, people ring-a-rosying as the light declines, and Deano camos himself, hunkered down in the corner. Play a bit of Tetris on the phone, take the mind off. Snivelling cunt, Wino. Benit and Candy are sitting on low stools in front of him, hiding him from view. Karl, rubbing his belly, plate in hand, says:

– That’s it boys. Time for me supper and he heads off back up onto the mezzanine.

That’ll be the fourth refill that Deano’s seen him get.

– Is that your real name? Benit says. Candy?

– Well, yeah but I changed it, like. Me mam gave me a stupid name. So I changed it to a normal one.

– Candy?

– Yeah.

– What was your other name?

– Pocahontas.

Jaysus. Deano pauses the game, looks up at the pair.

Benit stares at her, poker-faced. Then they both erupt. Benit’s laughing so much, he’s in danger of falling off his stool. It’s not that funny. They start into some convo about books and shite. Benit’s bullshitting for Ireland. Desperate for his hole. She’s smart though. Mental, but smart. Says she was doing three A-Levels before she came back. Then Jack happened.

– So, me and Mam came home for a wedding thing and then I was just in Dublin and then I met Jack in the Green and we just got chatting. He recognized me from photos. I’d no idea. Didn’t even know he was homeless, like. And we hadn’t seen each other since I was a baby. I didn’t even know him, you know?

– Yeah, he said, Benit says.

– Did he say much about me? Candy says.

– No.

– I loved him, you know? Proper. He was lovely, special, you know? she says.

Yeah, Benit does know. And so does Deano. And more than you, Missus. Silent tears are running down her cheeks. Fuck it, maybe she is really upset.

Benit puts his arm around her.

Deano catches Wino moving through the crowd still up on the mezzanine, glad-handing a few of the aul ones like a politician at Croke Park. He turns, throwing serious shade Benit’s way. Benit, oblivious, pulls Candy closer. That’s a mistake, by the look on Wino’s face. Deano sinks lower and gets back to his game. Sheedy’s was a bad idea.

*

The place quietens down when the coke-heads storm out to their waiting taxis – ready to shout their shite opinions into the faces of the barmen and punters in the clubs in town. Deano says he wants to head off. Benit, who’s out for the count, facedown on a pile of coats, gets dragged up by Deano and Karl, who apologize to the last of the women for the drool on their jackets. They search everywhere. Message him. Call him even. No sign of Hamza.

– Must have gone home earlier, Oisín says.

– Yeah, he wasn’t too bad, must be planning to go to school in the morning, after all, Deano says.

Rambling down the street, Benit yawns loudly and they stop at a lamppost. A pair of runners swings on the wire overhead.

– What did he say to you, Deano? Oisín says.

– Who?

– You know who. Wino. When you were up at his table talking to him. What’d he say?

– Haven’t a clue what yer on about, Deano says, staggering against the stone wall of the health board offices. Boys, I’m heading in here for a kip.

He drifts across the Weaver Park grass towards the playground, heading for the kids’ crawl-through pipes. Himself and Benit kipped in there one night last summer. One each. Just couldn’t make it home.

– Deano come on, your gaff ’s just there, Oisín shouts after him, but Deano just waves him off.

– Ah look, Deano, must be love! Benit says. Deano stops and turns around.

– Story? he says, as he walks back towards them.

In the laneway opposite, Deano can just about make out a couple facing each other holding hands. Big deal. He’s sleeping in the pipes. Tight and safe.

– No way I can go to school tomorrow, man, Benit says, pushing his do-rag back into position. Not after that.

– Lightweight, Karl says.

The couple in the lane breaks apart.

– That’s Candy! Karl says, as the girl comes out into the light on Cork Street.

– Someone got lucky tonight, Oisín says. Right, see yiz whenever, I’m heading.

The fella comes out of the laneway’s shadows, hands in pockets.

– Ah, hiya lads, he says. OK, so can I stay at yours, Oisín?

They stare at him, open-mouthed, as he strides past them towards Oisín’s.

– You are fucking joking, fam! Benit shouts after him. Hamza turns to face them.

– What? he says, shrugging.

2

KARL

On the Luas, Karl shifts out of the way of the woman with the buggy. Small and dark, linen dress, loafers. Brown Thomas, for sure. Balancing her iPhone and one of them bamboo coffee cups over her kid’s head, she looks Karl up and down and thinks better of saying thanks.

His mam’s voice’s in his head, banging on about having to leave his job in Penneys now that he’s in Leaving Cert, drowning out Kanye on the headphones. Would he have these AirPods if he wasn’t working? No. Would he have these VaporMaxes? No. Would he have been able to buy her the birthday nails voucher for that swank gaff in Donny-brook? No. There’s no chance, no chance, he’s giving up this job. And it’s not like he’s going to do amazing in his Leaving in anyway.

He shoots Deano a message.

Story. U going out after?

If he’s hurling, Deano won’t get back to him till lunchtime, but. At the earliest. Since the funeral and maybe Wino talking to him, Deano’s started this kinda snakey shite that Karl can’t quite work out. Wouldn’t even come out to help last night when Karl was giving the brothers a dig-out, collecting for the flats bonfire. Karl and Deano are a bit old to be at it for themselves anymore, but Deano’d never normally pass up the chance to help the flats out – even not his own flats – with a bit of collecting, carrying tyres over his shoulders, steering shopping trolleys full of crates. And Karl could’ve done with Deano’s long legs when he was trying to get back out over the warehouse wall with the pallets for Frankie and Jackie. Something’s not right with Deano but he’s telling Karl nothing.

*

He gets into the shop, dumps his bag in his locker and heads to the kitchen. It’s good when it’s quiet like this. The world is just beginning to wake up and you’re the only one there to see it.

The lads keep on at him that he needs to lay off the fries and get back to the hurling but seriously, who can say no to the full Irish before work? And he hasn’t actually played since primary school. Apart from the egg, he’s taken to grilling everything. Healthier. Doesn’t taste right but. This used to be his and Hamza’s thing, the brekkie in the morning. Then Hamo got the Brown Thomas job over the Christmas and that was it. Says it’s closer to home than trekking out to Dundrum but everyone knows it’s because he wants to hang out with the yuppies, studying them, as he says. Not that it’s all bad being out here without the boys. Sometimes, some things are kinda better without them.

Suddenly, his eyes are covered by hands that smell of strawberries. Tanya.

– Guess who? she says.

– Some Clonskeagh skank? he says, trying to sound bored.

– How’s my favourite chipmunk? I swear you’ll be the youngest heart-attack victim in the world with those breakfasts.

Tanya’s tanned. Like real tan, from the sun, in Spain. Not Salou, but. The family has a villa near Barcelona. So, she’ll be going for a little top-up at the mid-term, and the family pops over sometimes just for the weekend. Yeh know yerself. Then it’ll be into winter and skiing. She comes back with a tan from that too. It’s usually really sunny on the slopes, she says. The snow reflects the light. Karl never got a tan in Dublin during the big snow last year. That’s all Karl knows about tans and snow.

She called him on the second day of that big snow and brought over her snowboard and gave all the lads a shot of it in the Phoenix Park. Best day ever. The boys think he spends all his money on clothes. Not all. Some goes to the Credit Union – into the secret holiday fund. Karl’s going snowboarding for real. Maybe even skiing.

Tanya’s last working weekend next week. She fought with her parents to stay at it, but she has grinds starting on Saturdays and it isn’t like she needs the money in anyway. She wanted to get into Harvey Nicks, of course, or even House of Fraser but they were full up. She’s happy enough now though. Penneys is pretty cool. All modern behind the scenes, it is.

She slides into the seat beside him. He grins at her, chewing hard on a gristly rasher.

– Gonna miss me?

– Get over yourself, chipmunk, she says, swiping a sausage and taking a bite.

Karl grimaces. She knows full well that messing with the brekkie proper pisses him off.

– I’d better eat the rest of that, hadn’t I? Unhygienic for you otherwise, she says smiling, reaching for the sausage again.

He blocks her hand.

– Touch my sausage and I swear, I’ll bleedin batter yeh, he says, his mouth still full of rasher.

She pulls her hand back, wipes her shellacked fingers slowly on a paper napkin and arches one perfectly shaped eyebrow.

– I wouldn’t dare touch your sausage, Karl.

– Ah yeah? I wouldn’t give yeh the chance, yeh minger. She rolls her eyes.

– Aww, I love it when you do your skanger talk, Karlo. Do it again.

He cranks it up, enjoying himself now.

– You callin me common?

She laughs and sticks her feet up on the side of his chair, then puts a serious head on.

– Know the way I’m leaving here next week?

– Yup.

– Well …

Damien bursts through the door. Damo, the type of fella who wouldn’t go north of Lansdowne Road without a Garda escort. Except for that one time when he was a kid and his old mon brought him to a corporate box in Croker for the England–Ireland rugby match. The atmo was electric mon. The Bollinger was flewing. Damien couldn’t have been more than six or something – Karl looked it up – 2007.

– Hello, hello. Ready for another day, are we? Damien chirps like a thick-necked canary.

Damien has the entourage in tow. All the new ones, following him around everywhere he goes. Karl overheard him telling his groupies that his job title was ‘Customer Service Moving into Management’. Bit weird for a spa who only works Saturdays, but this lot are lapping it up. He’d have got a slap long ago if he’d started his crap round Karl’s way, straight up. That’s the problem with the likes of Damien, but. They’ve never got a slap, nor even the threat of a slap, and they never will get a slap, and that’s the end of it.

Damien’s told everyone his da is some big shot law fella or government fella or some shite like that. His da made him get a summer job, told him it’d be good for him, and now he’s still here at weekends. Damien’s kind’d normally be out playing rugby or whatever it is they do, but poor little Damien here has to hang out, tidying up the men’s sportswear. The supervisors keep finding him sloping around the bras, but. Been thrown out of lingerie at least three times, Karl’s heard.

– Hey, Ton! Looking gorge, Damien says.

– Hi Damien, she sighs.

– Doing anything I wouldn’t do this weekend? he says, resting his hands on her shoulders.

He’s fucking seventeen like. Acting like a fifty-year-old paedo. Karl pretends he can’t see Damien, finishes up the breakfast, staring straight ahead, crunching down on the crackly bit of egg, thinking of his ma. She makes the eggs soft and smooth. Karl can never manage it. Like feckin rubber, they are.

*

The morning passes quickly, busy from the start. Which is good. The day’ll fly and he wants to get out with the boys. Deano mostly. A woman crashes his daydream – asks him for the khaki capris in size ten. Ambitious, with those hips. Tells her that whatever they have is already out on the floor but then, looking at her disappointed face, says:

– Ah, no, maybe. I’ll go check in the stockroom for you.

He bounces along the hallway, checking his phone, opening IRQaeda group chat.

Deano:

Later P4F smoke, round Hamzas gaff, his ma in Pakiland

Hamza:

No way. Going mosque.

Deano:

Fuck off ya snake. Saturday no mosque. U smashing candy?

Hamza:

Nah, going mosque. No Candy.

Benit:

Ye right know u hittin dat she got jungle fever.

Hamza:

Am brown. Not black, nigga.

Benit:

Black enuf for candys jungle fever

Deano:

Some snake, leaving the boys for randy candy

Hamza:

Not with Candy. Leave her alone.

Deano:

Yup u hittin dat

Hamza:

Shut the fuck up.

This’ll go on and on. Hamza’s been denying it since the funeral, but Benit’s sure he saw them out in Blanch together, when Benit was out playing basketball with the black lads. And some of Karl’s Girls (as the group of fourteen-and fifteen-year-old flats girls call themselves) swore they saw Hamza down in Ringsend last week, with some young one with scarlet red hair. But when they shouted over to him, Hamza looked away, like he didn’t know Karl’s Girls (which Hamza definitely does). So maybe it wasn’t Hamza after all. Karl doesn’t get it. Not that he would. But none of the boys can. Candy, like?

He pushes open the outer door of the stock area. And that’s when he hears them, inside in the room.

– No fucking way, you can’t invite that pov. He’ll probably bring a gang of those scummers with him. Remember the time they met him outside here? Jesus, Ton. United Colours of Knackeragua. Cop on.

– You’re such an asshole, Damien.