7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Luath Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

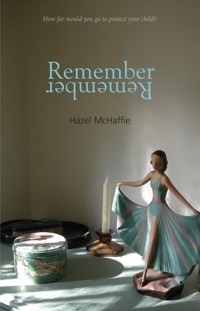

When Doris is found directing traffic in the middle of the night, her daughter Jessica is forced to put her in a home. Clearing out the family house in preparation for selling it, Jessica comes across secrets her mother kept from her long before her memory began to erode under Alzheimer's Disease. The knowledge Jessica uncovers as the family secrets are revealed and past memories are stirred, is fleshed out by the revelations Doris herself provides as her story unravels backwards. But the biggest secret of all is only brought to light when a medical research programme requires blood samples. BACK COVER The secret has been safely kept for sixty years, but now it's on the edge of exposure. Doris Mannering once made a choice that changed the course of her family's life. The secret was safely buried, but now with the onset of Alzheimer's her mind is wandering. She is haunted by the feeling that she must find the papers before it's too late, but she just can't remember...Jessica is driven to despair by her mother's endless searching. But it's not until lives are in jeopardy that she consents to Doris going into a residential home. As Jessica begins clearing the family home, bittersweet memories and unexpected discoveries await her. But these pale into insignificance against the bombshell her lawyer lover, Aaron, hands her. REVIEWS Hazel McHaffie has an extraordinary ability to create the convincing inner voice of a person with severe dementia. The result is often both funny and poignant. She raises emotional and ethical issues not as theoretical 'thin' cases, but within the richly characterised world of the novel... a good read from start to finish. PROFESSOR TONY HOPE This moving book will resonate with anyone who has 'lost' a loved one through the living death of Alzheimer's. SIR CLIFF RICHARD OBE It provides an amazing insight into the thought process of someone with dementia, as well as being a gripping and heartfelt narrative. JOURNAL OF DEMENTIA CARE This novel, I'm sure, will resonate deeply with family members and carers trying to cope wit this most distressing condition. Recommended. WWW.THEBOOKBAG.COM

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 283

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

HAZEL MCHAFFIE trained as a nurse and midwife, gained a PhD in Social Sciences, and was Deputy Director of Research in the Institute of Medical Ethics. She is the author of almost a hundred published articles and books, and won the British Medical Association Book of the Year Award in 2002.Right to Die,shortlisted for the Popular Medicine prize, was highly commended in the BMA 2008 Medical Book Awards.Remember Rememberis her sixth published novel set in the world of medical ethics.

Praise forRemember Remember:

It provides an amazing insight into the thought process of someone with dementia, as well as being a gripping and heartfelt narrative. JOURNAL OF DEMENTIA CARE

Praise forRight to Die:

There are very few novels which deal with the issues of contemporary medical ethics in the lively and intensely readable way which Hazel McHaffie’s books do. She uses her undoubted skill as a storyteller to weave tales of moral quandary, showing us with subtlety and sympathy how we might tackle some of the ethical issues which modern medicine has thrown up. She has demonstrated that hard cases make good reading. ALEXANDER MCCALL SMITH

…well written and researched…presents issues of medicine, law and ethics in a very human and readily understandable manner… BRITISH MEDICAL ASSOCIATION

We often talk about books being moving, but how many of them actually cause in the reader a strong emotional shift? We speak of books which make us think, but do they put such a fine focus on a subject that we come away feeling not only well-informed but having had our conscience exercised, or the working order of our moral compass checked? Hazel McHaffie’s novelRight to Diedoes all this and more… the issues it covers are highly topical and the questions it asks are hard ones, it’s an important book, too…its essential humanity and empathy lift it above ‘the mere facts of the case’.CORNFLOWER BOOKS

…a fine novel that travels with courage into difficult areas: incurable disease, euthanasia, suicide, faith, loss of personhood, hope and, ultimately, the nature of love in the face of serious illness. JOURNAL OF PALLIATIVE CARE

This is real life drama that’s a cut above the stories you find in weekly women’s magazines and it is hard to fault either the science or the emotions portrayed in the book…Wherever you stand on the issue, it will give you food for thought and would be an interesting title for a book club discussion, given the timeliness of the particular medical-ethical dilemmas debated.BOOKBAG

…stimulates [debate on] the ethical and moral issues brought about by modern medicine and the current law.THUMBNAIL

… very well researched, with medical and legal facts sprinkled liberally, but appropriately throughout…I recommend [it] to anyone who is interested in exploring the euthanasia debate, or looking for an emotional read.FARM LANE BOOKS

…helps the reader understand the emotions and difficult decisions behind the disease. ALS SOCIETY OF CANADA

An admirable attempt to tackle the issue of assisted suicide through fiction. ME AND MY BIG MOUTH

Remember Remember

HAZEL McHAFFIE

LuathPress Limited

EDINBURGH

www.luath.co.uk

First published 2010

This edition 2010

eBook 2014

ISBN: 978-1-906817-78-7

ISBN (eBook): 978-1-909912-83-0

The author’s right to be identified as author of this book under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 has been asserted.

The publisher acknowledges the support of Creative Scotland towards the publication of this volume.

© Hazel McHaffie 2010

Contents

Dedication

Acknowledgements

Family tree

Prologue

JESSICA

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

DORIS

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Postscript

Discussion Points for Bookclubs

To all the courageous men and women who have allowed me to walk alongside them on their journey through dementia.

Acknowledgements

Without the generosity of many people living with dementia I would never have been able to write this book. They have taught me more than they ever knew and it has been a privilege to be part of their lives. Respect for their rights to privacy precludes me from naming them but I thank them all comprehensively. Random conversations with numerous people involved in the care of people with dementia, in homes and organisations, over decades have also helped to shape my thinking. I am constantly amazed by them.

Dr Gwen Turner and Dr Richard Turner, who have a wealth of personal as well as clinical experience between them, gave me invaluable advice on an early manuscript which helped to shape the final version of this story, and I thank them warmly for their friendship and expert help. Professor Tony Hope is one of the most encouraging people I know, and I’m indebted to him for his ongoing support and reassurance, particularly at a time when he was working on his own major report about the ethical issues associated with dementia.

I’m grateful too to the team at Luath Press, and in particular, to my editor, Jennie Renton, who highlighted my faults but left me to correct them – exactly the right way to handle me! Nele Andersch proved a real friend when I needed one.

And as always, I am indebted to my family for their constant support and love. Jonathan, Rosalyn and Camille read drafts with affectionate prejudice. David meticulously proof-read the final version and gave me the space I needed to get lost in this story.

Family tree found in a handbag at Bradley Drive

Prologue

SIMON ARRIVED EARLYfor his lecture. He wanted time to size up his student audience and plan his tactics.

As the latecomers slouched in, his brain rehearsed details of the case he intended to present. He’d need to tread extra warily – too much information could so easily betray confidences.

Professor Duncan was on his feet; the buzz of young voices died.

‘Good morning. May I remind you to switch off your mobile phones, please. I’m sure the world can cope without your pearls of wisdom for 90 minutes on this particular Thursday morning.’ A pause while everyone checked. ‘Thank you. I can assure you the sense of bereavement will soon be forgotten, because our guest speaker today is Simon Montgomery-Bates. As a practising lawyer, author of six legal texts, and with something of a reputation as an after-dinner speaker, he brings a wealth of experience and skill to his presentations. I can promise you, you will be challenged, you may be shocked, but you will not be dozing during this session. And that includes you three on the back row who seem to be settling down for some kind of slumber party.’ A ripple of appreciation. ‘So, without further ado, Simon.’

Simon strolled forward, adjusting his bow tie, and let his gaze wander over the faces. Only when he had their full attention did he start to speak. He began to pace, one hand behind his back, the other clutching his lapel. All eyes followed him.

‘Ladies and gentlemen, the case I bring before you today bears all the hallmarks of a cause célèbre. We have an elderly widow with aristocratic connections and inherited wealth. We have attempted murder.’ A pause. ‘We have a lawyer-lover with a conflict of interests… no, not me, I can assure you! We have issues of mental competence; a cuckoo in the nest; tension between potential inheritors; a will that must remain sealed until the testator dies; secrets and deceptions that span decades. And yet,’ he raised one finger, ‘this is an ordinary family. They might be living next door to you… or to me. (Contrary to campus rumour, I do inhabit this planet, despite my Vulcan-like logic and detachment.) It’s highly unlikely that the names of any of these people will hit the headlines, or that they will ever appear before you in the High Court. Nevertheless, their situation poses a number of legal challenges.

‘We’ll begin with the eldest daughter of the widow, Annie. And before you start texting the News of the World, Annie is, of course, not her real name. Annie is in her sixties and in the process of clearing the family home. You… yes, the young lady there, in the red jumper… you are Annie. You grew up in this house. You love every stone of it. It’s full of memories. How are you feeling, dismantling your history?’

‘Sad? Angry? Torn?’

‘Indeed. I’m glad you included angry, because you have a brother and a sister who also grew up in this house, but they…’

JESSICA

Chapter 1

IT WAS IN THIS room that I almost murdered my mother.

My hands were actually starting to press down on her shoulders. As she sank she grabbed for the rail, missed, and began to flounder. A wave of water went over the side of the bath, soap stung my eye. I groped for the towel. By the time I could see again my rage had passed.

Looking back now, I still wonder. Would it have been better to have ended it that day? Maybe once this house is sold I shall get some kind of resolution.

The bathrooms were top priority as soon as Mother was admitted to the home. It was the smell; no amount of scrubbing or bleach would eradicate it. Floors, suites, tiles, everything had to go.

It’s a big concession having men in to do the tiling. But James was insistent. ‘OK, do the painting and papering yourself, if you must, but let me organise the bathrooms.’

They’re only young, Jake and Richie, fingernails encrusted with grout, but in a few hours they’ve finished upstairs and down. No cracks, no misalignments.

‘Nice choice, Mrs B,’ Jake said. ‘Can’t go wrong with white.’

Oh yes you can. Mother had white in here before…

‘We’ll be back tomorrow to finish the grouting. You’ll be all hunky-dory by teatime.

But I’ll be glad when they’ve gone. It’s painful having strangers in this house that’s so full of family ghosts.

It’s not the same for James.

I can see her now, the week before she was admitted to The Morningside. Hard to believe it’s been almost a year.

It was such a warm day for March I wanted to fling open all the doors and windows… except that anything open represented an escape route to my mother. She shuffled into the hall and stood passively, waiting to be led. I took her hand and inched her from room to room, willing the old familiarity to spark something in her brain.

But a packet of Ginger Nut biscuits lying on the kitchen surface generated more interest than any of my prompts. She spent 10 minutes trying to pick a flower off an embroidered cushion. I tried to distract her, like they said, showed her family photographs: no response.

The last time she’d been in this house she’d given the appearance of knowing where she was. Now even that veneer had gone. Hope died within me.

Now I have the house to myself again, I can get on with emptying cabinets. At least the kitchen doesn’t need redecorating having been completely gutted and refitted after the fire.

It had a fair hold before Bert, the postman, called the Fire Brigade. Bert knew all about Mother and when he’d smelt burning he’d charged straight into the house to check she was safe. It was empty. Mother was skulking behind the garden shed, a singed teacloth in her hand. ‘Have you come for tea?’

She’d left an empty saucepan on the electric ring, the fire chief said, then she’d dumped a pile of towels and teacloths on top of it.

‘She has Alzheimer’s,’ I explained.

‘And she lives on her own?’

The criticism stung. I’d already removed bleach, medicines, matches, scissors and knives. I visited her daily, cooked, cleaned, ironed, shopped, stuck labels on everything to remind her what it was. I phoned her frequently to check she was still there, still pretending.

It was a bleak moment standing there amidst the devastation she’d caused, facing the only possible solution.

On paper, of course, I was not alone with this.

When the diagnosis was finally pronounced my uncles, Sydney and Derek, did visit, together for moral support. But Mother dredged up an Oscar-winning performance. Her only sister, Beatrice, who saw more of the deterioration, spent so much time talking about her ailments and her activities it was doubtful whether she even registered the implications of the illness.

To an extent I could excuse that generation on account of their own advancing years, but I’ve felt far less forgiving of my own. Eugene, living in Australia, had a cast-iron reason for leaving things to me. And to be fair, he rang, he commiserated, he suggested buying in help, offered financial assistance. My younger sister, Adeline, technically should have shared the responsibility. Technically. She has more money (she works in advertising; her salary is obscene) and more time (no children or grandchildren). But in her position, she ‘cannot afford’ the slightest whiff of anything ‘unsavoury’ in her background.

And so I’m the one still taking responsibility for Mother. She may no longer be physically in my charge, but her house is.

The task of getting it into order was overwhelming, so I’m tackling a room at a time. Kitchen first – least demanding, least emotionally draining. Anything I find in these cupboards got there within the space of eleven months – the time I lived here with Mother after the fire. I make rapid progress. Cooking paraphernalia… charity shop. Shrivelled vegetables, dubious packets and tubs, glue dots, erasers, half-eaten biscuits, sticky jelly babies… straight in the bin. Nothing of any significance. Then, at the back of one of the base units, I find a box tied up with string, the knot so intricate that Houdini would have been daunted. I resort to scissors. It feels sacrilegious.

Inside I find… a treasure trove. Drawings by grandchildren; an invitation to an art exhibition in Glasgow; a school note saying Eugene has won a special Governors’ ‘Overall Improvement’ prize; a newspaper clipping showing Adeline and me holding a turnip at some agricultural show; a bundle of letters held together with a red elastic band (assorted senders: Grandmamma, Lionel, the Palace of Holyrood, me, the electricity company, social services, James, Jenners, George)…

I close the shoebox and carry it through to the hall. So many stories lie in that single hoard. Those impenetrable knots – perhaps this was Mother’s way of protecting her past; if she couldn’t get into the contents she couldn’t destroy them.

Tucked down the side of the adjoining cabinet I find an old sepia photograph of Mother’s family. The names are written on the back in a beautiful rolling hand, not hers: JACK, SYDNEY, DORIS, DEREK, BEATRICE, MAMMA. But both the name, Doris, and her face are covered in heavy ink scratchings. How sad. Was Mother aware that her identity was being eradicated by this crippling illness when she removed herself from the portrait? What must it do to a person to contemplate their own living extinction?

I let my thumb glance over the blackened spot where she once smiled. Doris: eldest daughter, mother, grandmother. It’s too easy to forget those years in the ongoing struggle with dementia.

I slip the photo into the shoebox in the hall, my mind still in the past.

The holes in the frame of the front door jerk my mind on to another crisis.

I’d only gone down to the newsagents. Ten minutes running there and back, not stopping to talk to Eunice McClarity, not waiting for the pedestrian lights to turn green. I’d left Mother asleep, knowing I must be back before she wakened.

The futility of trying to fit my key into the keyhole took a while to penetrate. It must fit. It must!

I tried a nail file. I tried phoning. I tried an appeal. ‘Mother. It’s only me, Jessica. Open the door for me, there’s a dear.’

I listened through the letterbox. What did silence denote? Unlit gas… electrical sockets… steep stairs… every hazard raced through my mind.

The policeman was sympathetic but brutally pragmatic. ‘Only one way in. Break the lock. We cannae just slip a slice of plastic in, and bingo. Doesnae work like that. But I can give you the name of a reliable bloke who’ll repair the door.’

I had no choice.

All my anxiety about the trauma of an SAS-style invasion proved groundless. Mother was oblivious to the whole operation, lying fully clothed in two inches of hot water in the bath, her head encased in a towel and fur earmuffs, her slippers soaking in the lavatory pan.

‘Did I invite you?’ she said – not to the assorted strangers storming her house; to me. Then, ‘Ring the pope. He’ll know.’

It was the last time I left her unattended.

As I pick up the sack of foodstuffs and drag it to the back door, I can’t resist a wry smile at how cross Mother had been that time Pandora tore through her cupboards, ‘saving’ her from food poisoning.

‘In my day there was no such thing as sell-by dates.’

‘Gran! It’s gross.’

Pandora. Light years away from Mother’s chaos. Judged against Pandora’s standards we are all incompetent. I wish I could rid myself of this nagging anxiety about my daughter.

But there’s work to be done before James arrives to remove the boxes and bags. Dear James. What would I do without him? I know he’ll be there until this job is done, whatever his own private reservations.

‘Yoo-hoo. Anybody at home?’

‘In the kitchen, James,’ I sing out.

‘Wow, Mum. You’ve certainly made inroads today.’

‘Scrubs up pretty well, huh?’

‘Certainly does.’

‘I’m impressed. I’ll heft these boxes out to the car, then we’ll have the space to see what’s what.’

He picks up the shoebox.

‘Not that one, James.’

‘I hope you’re not taking more of Gran’s junk back to your house,’ he says, looking at me sharply.

It’s fair enough. I can only pray I live long enough to sort everything out in my own home, so that he’s spared this task. I often think Mother will outlast me. She’s a tough cookie. She’s survived having twice as many children as I had. Her diet has been frugal but wholesome, whereas I’ve fallen into the bad habit of comfort eating. And her life now is far less stressful than mine. In a way I envy her this final freedom from responsibilities for bills, relationships, tax returns, meals, inherited genes…

But then, she’s already paid her dues. As I tried explaining to Aunt Beatrice.

‘Remember all the years she struggled. Look at everything she did for everybody else. I want her to have some luxury now.’

‘Luxury’s wasted on her. So’s sacrifice, come to that.’

‘Even if she doesn’t appreciate it, I want to know she’s getting what she deserves.’

‘Doris would have wanted her family to have everything, not to waste money on her.’

I don’t tell Beatrice the other reason. The guilt I feel.

Chapter 2

GUILT, REGRET, DESPAIR– I experienced them all in this front bedroom. It was so hard to come back. I thought I’d left it for good when I walked out of it as a bride40years before. But that mad autumn there was no other viable option. Neighbours, strangers, the emergency services – it wasn’t their responsibility to rescue Mother from the predicaments her chaotic mind got her into and no one else in the family could find space in their lives for her. So that left me.

Having a bolt-hole of my own had become a dangerous indulgence.

Today this room feels naked compared with the rest of the house, although the burgundy throw I brought with me from my own home is still on the bed. The piles of unused gifts, the broken implements, unread magazines,29bottles of oil and eleven containers of bleach, boxes of corsets, liberty bodices and vests, Lego, blankets, icing sugar, four wirelesses, a slashed pouffé… all this clutter had to go before I could reach the bed. I couldn’t afford to dither around recycling things, I simply pushed everything into the garden shed and disposed of it in the refuse collection surreptitiously, so as not to let another living soul glimpse the extent of the pandemonium in my mother’s head. Not even James.

I clung to the hope that, once she settled down with me in constant attendance, she would become more biddable, my dislocation would become more bearable. It never did. I sank exhausted into bed, rarely getting more than a couple of hours’ sleep before I was summoned by sounds of the prowling insomniac.

I bundle up the quilt and squash it into a black sack.

The furniture is flimsy in here, but my lower spine still protests as I inch it into the centre of the room. It would make excellent timber for a bonfire. I must ask James. His boys used to love making fires with him at the bottom of the garden. I picture them, swathed in the bright scarves and hats I knitted for them, crouching alongside their father, toasting marshmallows.

Perhaps not. The ‘children’ are scarcely that any more. Leanne is taller than me now. Blake ended up in a police station in December, for shoplifting a box of Roses chocolates – ‘for his nana’, he said. And where Blake goes, his younger brother, Rafe, aspires to go.

I peel back the carpet. An antique smell leaks into the room. I throw open the window but once I start to strip off the first sheets of wallpaper, I no longer notice it anyway. This is one DIY job I do enjoy. I don’t know why – a psychologist probably would. The paper is so old and dry that it lifts off in crispy swathes.

It bears the marks of nail polish and felt-tip pen and latterly, tomato paste.

Mother was supposed to be dozing in the conservatory. I’d been out in the garden hanging yet another row of sheets on the line, but… the wicker seat was empty. This bedroom was like a scene from Armageddon. I wonder, now, was she trying to paint herself back into her own territory?

From the window I can look down on the garden. The memories are kinder. Mother kneeling on the lawn, weeding; Mother raking the autumn leaves; Mother pushing the children on the swing.

‘Higher, Granny D, higher!’

I see Pandora’s pigtails being flung around in the sheer effort to touch the sky. I hear my mother’s laughter floating across the lawn as she sends her granddaughter swooping upwards, the creak of the chains, the child lifting herself right off the seat, my breath catching in fear.

Pandora. Why did I take so long to notice my daughter’s obsessive streak? She has always yearned for prestige, always cared about appearances. Aged eleven she changed the names of the family cats from Poppy and Smudge to Lady Petunia and Lord Montmorency. Should I have insisted she seek professional help when the fads evolved into compulsions? It hurts – both the behaviour, and the responsibility for it.

I keep hoping that age will soften some of the excesses but I see no sign of it. Gym-toned and botox-rigid, she finds my ‘slovenliness’ a sore trial. She’d like me to be an elegant granny for her children but I do not answer the job description. Privately, I’m a disappointment to myself as well. Why can’t I manage to keep in shape – mentally and physically? But ageing is disappointing. Health fails, memory lets you down, everything sags, the children don’t need you, friends die, dreams fade. Maybe Mother’s been spared something worse than confusion: clarity of vision! Why don’t we revere and respect the elderly in our culture, value their wisdom? Mother is why. I am why.

Pandora has consigned her grandmother to the past tense. I can understand that, but it still hurts. This is her old playmate and ally, the person who used to be first on her prayer list.

Thank goodness for James. He remains totally in league with his beloved Gran. And he seems to know intuitively how to treat her. I’ve had to learn.

Once we had the diagnosis, they gave me lists: all the things you should never do with someone who has Alzheimer’s. Absolutes, they call them.

Never argue; always agree.

Never reason; always divert.

Never lecture; always reassure.

Never condescend; always encourage or praise.

Never force; always reinforce…

Ten commandments. I pinned them up and kept looking at them, catching myself in error at least15times a day. They started to sink in… only to desert me when she drove me beyond reason.

Never shame; always distract.

You try not showing disgust when your toes slide into somebody else’s poo in your slippers!

Never say ‘You can’t’; always do what they can do.

When she’s brandishing a carving knife? Hello! Reality check!

Never command or demand; always ask.

Yeah, right! ‘Mother, would you be a dear and consider letting go of my neck? You seem to be strangling me.’

Never say ‘I told you’; always repeat.

Always repeat! How many millions of times can a human being cope with saying, ‘No, Mother, you didn’t invite me. I’m your daughter, Jessica. This is my home.’

If I hadn’t ever heard of the commandments I’d have been spared this additional layer of guilt at least. But it did get easier to trust my instincts and accept compromises. Nothing was going to restore Mother to her pre-dementia lucidity, so I could happily agree to anything. And because she wouldn’t either understand or remember what I said, I could release my frustration by adding nonsense of my own.

‘Did I invite you?’

‘No, but do please feel free to invite me in next time you decide to empty all my geraniums into the sink.’

‘Is that you, George?’

‘Well, not last time I looked, but I’ll keep checking.’

‘Where’s my purse?’

‘Let me see, it might be under the holly bush, or in the bath, or burnt to a cinder. Or it might never have existed.’

As she withdraws further and further from reality, I do periodically take stock and check that I’m not wandering into unacceptable realms. Especially when she and I are all alone.

Stay calm and patient, they say.

Try that when you’re permanently deprived of sleep, tormented and exhausted yourself,Isay.

Focus on a word or phrase that makes sense, they tell you.

And just how many times a day would that apply to the same word?

There is no off-duty, no annual leave, no retirement. At least there wasn’t, until I put Mother into The Morningside.

Which is why I’m stripping this room and closing down the family home.

There, that’s the paper all off. A cup of tea calls.

I take the mug outside and look up at the house from the garden seat. It’s a solid building, well proportioned. It should fetch a good price. Enough to pay… say it quickly… £968.80 a week – a week! £50,000 a year. As long as she doesn’t live too long beyond the doctors’ predictions, and inflation doesn’t double that figure.

Given the sums involved, I needed my siblings to help me make the decision about selling. Eugene left the final word to me.

‘Jess, you’re the one who’s seeing Mother all the time. If it means selling the old house to pay for the care, that’s fine by me. You’re the boss. I must try to get back before she forgets who I am.’

It’s probably too late for that, Eugene. But how about coming for me?

My sister, who ‘pops up’ from London once a year and has never taken responsibility for Mother, didn’t let that hold her back.

‘I don’t know, houses are a sound investment. Once it’s sold, that’s that. If we hang on to it, it will keep appreciating in value. You could think about letting. There must be a big demand for rented properties in Edinburgh.’

I shouldn’t have been surprised. Her response to Mother coming to live with me had been even more breathtaking.

‘How about if I try to free up a week in the summer? We could go shopping, do things together like we used to. A bit of retail therapy works wonders.’

‘What about Mother?’

‘She’d be OK for a couple of hours, wouldn’t she?’

‘No, Adeline, she would not. She can’t be trusted alone for a couple of minutes, never mind hours. She needs constant supervision.’

‘Oh. I see. Well, why don’t we buy in some help for that week? I’ll share the cost. They could look after her while I take you out shopping. My treat.’

I kept the explosion for James, who was typically pragmatic.

‘Don’t give it another thought, Mum. Gran has to go into care, and the only way we can afford the kind of care we want for her is to sell her house. Full stop. Adeline’s loaded, she doesn’t need Gran’s money. Uncle Eugene says do what you have to do. You – and Pandora and me – all say, sell up to pay for somewhere decent. End of story.’

Aunt Beatrice rang at 11 in the evening to add her opinion. I’d just battled Mother back into bed for the third time and flew to stop the phone wakening her again.

The preliminaries were cursory. She clearly had an agenda.

‘D’you know what’s in her will, Jessica?’

‘No. Why?’

‘What if she’s specified who the house goes to?’

‘While she’s alive her own needs take precedence, surely? Whatever the house makes is for her benefit.’

‘You’re her executor, aren’t you?’

‘James and I both are.’

‘And that was Doris’s choice?’

‘It was. We did it all properly when she was perfectly competent to make that decision and hand over power of attorney against the day when she couldn’t decide for herself.’

‘Hmm.’

‘It makes sense, doesn’t it? I’m on the spot. And James is good on the money side.’

‘And he’s your son.’

‘But we’ve consulted Eugene and Adeline on everything. We’re presuming Mother will have left the house and her possessions to all three of us children equally – or our heirs. If you know differently, now’s the time to say so.’

‘It’s just that I know Adeline isn’t happy.’

My sister was defensive when I reported this conversation.

‘I only asked Aunt Beatrice what she thought because you didn’t seem to be listening to what I wanted at all.’

‘I was listening, but all you could talk about was shopping! Mother’s a danger to herself and everyone around her these days. I don’t seem to be able to get you to accept the fact she needs supervision 24/7. We don’t want to dump her in some grotty place.’

‘No, of course we don’t…’

‘Even if we went for no more than the basics, we’d have to sell. I thought you agreed to go for the best. She’s our mother!’

‘Well…’

‘She doesn’t need her house any more. And it’s her house. Her money. For her care.’

‘Aunt Beatrice reckons we ought to know what’s in the will before we decide.’

‘Well, we can’t. The lawyer told us that we can’t. Mum insisted.’

‘You might be going against her wishes.’

‘Adeline, if you have a problem with me dealing with Mother’s affairs, why don’t you come right out with it? I can’t be doing with all this...’

‘It’s not easy, being down here…’

‘OK, how about a swap? You come up here and take care of Mother and I’ll stay in your flat until you’ve decided what’s best.’

‘Don’t be silly. What about my job?’

‘I used to have a job too, remember? I was a teacher six years ago.’

‘How much money does Mother have in the bank? Is there enough to keep her in the home for a couple of years, and then see if… well, if she’s still around?’

‘For goodness sake! If James and the lawyers say it isn’t enough and we have to sell the house, that’s enough for me. This is James we’re talking about. Her grandson. Look, if you can see any other way of finding the money, then talk to the lawyers yourself. But remember, Mother’s still here needing round-the-clock care, so it’d better be this week rather than next year.’

‘There’s no need to snap, Jessica. I’m only asking. I’m reliant on other people to fill in the gaps.’

‘So tell me, what do I do with Mum? Because something has to happen. Things can’t go on the way they are.’

‘Let me think about it. I’ll get back to you.’

Adeline has an unnerving ability to shake my confidence. What if Mother has left the house to someone specific? I ring the lawyer, but he reiterates: ‘Mrs Mannering’s stipulation is, none of the family may know the contents of the will while she’s alive.’ He can’t go against that instruction without her consent, and she’s in no position to consent to anything, but he confirms that the sale of her house in the current circumstances conforms with the spirit of her wishes.

On hearing that, Adeline sniffed; Aunt Beatrice maintained her silence.

Neither can find a slot in their busy schedules for a trip to Scotland. Not even for shopping.

Today when James arrives, the will crops up in conversation and he has another conundrum for me.

‘I’m not sure if I’m meant to tell anybody about this, but since we’re talking finance… over the years, sums of money have been deposited in Gran’s bank account. Sizeable sums. Anonymously. Do you know anything about them?’

‘No.’

‘Hmm. Odd.’

‘Have you asked the lawyer?’

‘Yep, but he doesn’t know – or won’t say.’

‘Maybe it’s Adeline’s conscience-money!’ I say.

‘Without broadcasting her generosity? I don’t think so.’

‘Maybe Mother has a secret admirer.’

‘A billionaire toyboy!’ he laughs. ‘Way to go, Gran!’

‘It’s not impossible, you know. Just because a woman’s past her prime, doesn’t mean…’ I didn’t intend the heat.

I turn away and apply myself to filling another hole.

‘Mum?… Do I smell a story?’

‘It’s nothing.’

‘The kind of nothing that makes my mother blush? Come on.’

I can’t.