19,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

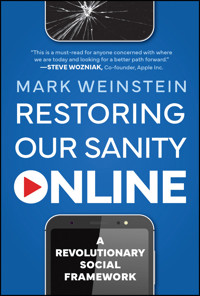

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Wissenschaft und neue Technologien

- Sprache: Englisch

“This is a must-read for anyone concerned with where we are today and looking for a better path forward.”

―Steve Wozniak, Co-founder, Apple Inc.

Big Tech is driving us, our kids, and society mad. In the nick of time, Restoring Our Sanity Online presents the bold, revolutionary framework for an epic reboot. What would social media look like if it nourished our critical thinking, mental health, privacy, civil discourse, and democracy? Is that even possible?

Restoring Our Sanity Online is the entertaining, informative, and frequently jaw-dropping social reset by Mark Weinstein, contemporary tech leader, privacy expert, and one of the visionary inventors of social networking.

This book is for all of us. Casual and heavy users of social media, parents, teachers, students, techies, entrepreneurs, investors, and elected officials. Restoring Our Sanity Online is the catapult to an exciting, enriching, and authentic future. Readers will embark on a captivating journey leading to an inspiring and actionable reinvention.

Restoring Our Sanity Online includes thought-provoking insights including:

- Empowering You—Social Media User, Content Creator

- In The Crosshairs: Privacy And Anonymity

- Saving Our Kids From The Abyss

- Surprise! Social Media Can Be Good For Your Mental Health

- Is AI The High-Tech Tattletale In Your Social Experience?

- Lifting the Veil On Bots and Trolls

- Facts, Opinions, Lies—Who Decides?

- Web3 Is Here—What The Heck Is It?

- Is There a Better Way?

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 339

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Ähnliche

Table of Contents

Cover

Table of Contents

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Introduction

1 My Adventures in Web1 and Web2: The Rise of Surveillance Capitalism

Web2: The Rise of Surveillance Capitalism

2 Uncanny Parallels: Big Ag, Big Energy, Big Tech

In the Beginning

Monopolistic Consolidation

Monopoly Practice: Short-Term Profits, Short-Changed Customers

Monopoly Practice: Turning off the Lights of Competitors

Purposeful Misinformation and PR Spin

Armies of Lobbyists

The Damaging Impacts of Big Ag, Big Energy, and Big Tech

Fines Are Ineffective

3 Promising Movements Afoot

Big Ag: Regenerative and Organic Farming

Big Energy: Renewables and Electric Cars

Where Does This Leave Big Tech?

4 Web3 Is Here: What the Heck Is It?

Web1

Web2

Welcome to Web3

The Promised Benefits of Web3 for Social Media

5 A Healthy Dose of Web3 Reality

Tectonic Trouble

6 Meet Your New Boss, Same as the Old Boss

7 Is There a Better Way?

What Is Conscious Capitalism?

Conscious Capitalism for Restoration Networking

8 Empowering You: Social Media User, Creator, Star

The Slog to Stardom

Sharing the Spoils

9 Do I Need a Social Media Wallet: Is There Money in It?

Restoration Networking Wallets

10 How Do We Overcome C-Suite Tyranny?

User Advisory Board

The Restoration Networking Institute

Changing of the Guard

11 In the Crosshairs: Privacy and Anonymity

What Does Privacy Really Mean?

How Does Anonymity Differ from Privacy?

A Brief History of Privacy

Laws Protecting Privacy

Privacy’s Stronghold: Encryption

12 User ID Verification: Friend or Foe?

Pitfalls of Anonymous Platforms

Time for User ID Verification?

Big Tech Gets Verification Wrong

Reality Check—Our Data Abounds

Putting What’s Known to Good Use

Who Does the Verifying?

Pseudonyms to the Rescue

Long Live Privacy; RIP Anonymity

13 Saving Our Kids from the Abyss

Some Benefits of Social Media for Teens

Social Media’s Harms to Kids and Teens

Meta’s Purposeful Disregard

It’s Not Just Meta

Band-Aids on Gaping Wounds

Restoration Networking Solutions to Protect Kids and Teens

How Parents Can Protect Their Kids Right Now

14 Surprise! Social Media Can Be Good for Your Mental Health

How to Protect Your Mental Health on Social Media Right Now

15 Is AI the High-Tech Tattletale in Your Social Experience?

AIIs Not New, But It Has Crossed the Rubicon

AI Know-It-All: Friend or Creep?

The AI Roadmap for Restoration Networks

16 Lifting the Veil on Bots and Trolls

What Exactly Are Bots and Trolls?

Restoration Networking Solutions on the Way

Tips for Defanging: What You Can Do Right Now

17 Balancing Act: Free Speech versus Moderation

The Six-Point Action Plan for Authentic Civil Discourse

Supporting Section 230 with Careful Reforms

18 Facts, Opinions, Lies: Who Decides?

The Checkered History of Fact-Checking

True Lies

The Streisand Effect

A Misleading Warning

Restoration Networking for Information Seekers

Hybrid Reviews

19 Seven Lessons for the Street Fight

Lesson 1: The Myth of Inevitable Dominance

Lesson 2: Change Comes from the Outside

Lesson 3: Don’t Give Up, Embrace Alternatives

Lesson 4: Customers Willingly Pay for Healthy Choices

Lesson 5: Reward Customers with Dividends

Lesson 6: Third-Party Certifiers Build Trust

Lesson 7: Regulations Work with Real Teeth

20 Welcome to Web4: The Restoration of Sanity

The Restoration Networking Constitution

Bringing It All Together

21 Taking It to the Streets

Appendix A: Advice to Legislators

Protect Kids from the Social Media Abyss

Reform Section 230 to Safeguard Fair Competition

Respect the First Amendment Rights of Social Media Companies

Antitrust Reforms to Take On Monopolies

Taming AI

Appendix B: Accountability Structures for Restoration Networking

The Restoration Networking Constitution

The Restoration Networking Institute

Restoration Networking Certification

Restoration Networking User Advisory Boards

Appendix C: Revenue Superchargers

Freemium

Ethical Advertising

Revenue Sharing with Creators and Page/Group Owners

Featured Pages and Groups

Helpful Tools for Creators

Donations

Appendix D: Seven-Point Prescription to Vanquish Bots and Trolls

Notes

Introduction

Chapter 1: My Adventures in Web1 and Web2: The Rise of Surveillance Capitalism

Chapter 2: Uncanny Parallels: Big Ag, Big Energy, Big Tech

Chapter 3: Promising Movements Afoot

Chapter 4: Web3 Is Here: What the Heck Is It?

Chapter 5: A Healthy Dose of Web3 Reality

Chapter 6: Meet Your New Boss, Same as the Old Boss

Chapter 7: Is There a Better Way?

Chapter 8: Empowering You: Social Media User, Creator, Star

Chapter 9: Do I Need a Social Media Wallet: Is There Money in It?

Chapter 10: How Do We Overcome C-Suite Tyranny?

Chapter 11: In the Crosshairs: Privacy and Anonymity

Chapter 12: User ID Verification: Friend or Foe?

Chapter 13: Saving Our Kids from the Abyss

Chapter 14: Surprise! Social Media Can Be Good for Your Mental Health

Chapter 15: Is AI the High-Tech Tattletale in Your Social Experience?

Chapter 16: Lifting the Veil on Bots and Trolls

Chapter 17: Balancing Act: Free Speech versus Moderation

Chapter 18: Facts, Opinions, Lies: Who Decides?

Chapter 19: Seven Lessons for the Street Fight

Chapter 20: Welcome to Web4: The Restoration of Sanity

Chapter 21: Taking It to the Streets

APPENDIX A: Advice to Legislators

APPENDIX B: Accountability Structures forRestoration Networking

APPENDIX C: Revenue Superchargers

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Index

End User License Agreement

Guide

Cover

Table of Contents

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Introduction

Begin Reading

Appendix A: Advice to Legislators

Appendix B: Accountability Structures for Restoration Networking

Appendix C: Revenue Superchargers

Appendix D: Seven-Point Prescription to Vanquish Bots and Trolls

Notes

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Index

End User License Agreement

Pages

i

v

vi

vii

xi

xii

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

59

60

61

62

63

65

66

67

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

109

110

111

112

113

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

153

154

155

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

172

173

174

175

176

177

178

179

180

181

182

183

184

185

186

187

188

189

190

191

192

193

194

195

196

197

198

199

200

201

202

203

204

205

206

207

208

209

210

211

212

213

214

215

216

217

218

219

220

221

222

223

224

225

227

228

229

230

231

232

233

234

235

236

237

238

239

240

Praise for Restoring Our Sanity Online

Three and a half decades ago, when I invented the web, the intention was to allow for collaboration, foster compassion, and generate creativity. It was a tool to empower humanity. Yet in the past decade, instead of embodying these values, a few social media platforms have played a part in eroding them. Restoring Our Sanity Online reveals the web’s fascinating journey with powerful anecdotes. The book’s call to action for a human-centered web aligns with my original vision. Mark Weinstein presents a new paradigm for the web and social media that empowers users, reshapes data storage around user-controlled Solid Pods, protects democracy, and eliminates surveillance capitalism. Its vision, which I share, is a digital future that prioritizes human well-being. This is a vital read.

—Sir Tim Berners-LeeInventor of the Web

Technology has a purpose: to do good and to share. Restoring Our Sanity Online is a timely and essential read for those seeking an approach to social media that aligns with this. Mark Weinstein offers a refreshing vision—users are customers to serve, not products to sell. The book presents practical solutions for social media that doesn’t rely on tracking users or targeting them with ads. It provides a blueprint for sharing profits with users while championing privacy, mental health, and authentic connections. This is a must-read for anyone concerned with where we are today and looking for a better path forward.

—Steve WozniakCo-founder, Apple Inc.

Mark Weinstein has long been a leading voice advocating for the responsible use of social media. In this important book, he brings decades of wisdom to bear on one of the most consequential issues of our times—how we can deploy the extraordinary power of social media and AI in ways that align with our collective well-being over the long term. This is essential reading for business leaders, policy makers, and citizens at large.

—Raj SisodiaCo-founder, Conscious Capitalism Inc.

Mark Weinstein’s Restoring Our Sanity Online is a compelling journey into the heart of the digital age, where the promises of social media collided with the stark realities of its influence on our lives. Combining personal anecdotes and a critical analysis of Big Tech’s evolution, Weinstein offers a hopeful narrative on how we reclaim the internet for its intended purpose–connection and community. This book is a must-read for anyone looking to understand the impact of social media and seeking practical solutions to create a healthier online environment.

—Dr. Marshall GoldsmithBestselling author, The Earned Life; Triggers; What Got You Here Won’t Get You There

MARK WEINSTEIN

RESTORING OUR SANITY ONLINE

A REVOLUTIONARY SOCIAL FRAMEWORK

Copyright © 2025 by Mark Weinstein. All rights reserved.

Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey.

Published simultaneously in Canada.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400, fax (978) 750-4470, or on the web at www.copyright.com. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, (201) 748-6011, fax (201) 748-6008, or online at http://www.wiley.com/go/permission.

Trademarks: Wiley and the Wiley logo are trademarks or registered trademarks of John Wiley & Sons, Inc. and/or its affiliates in the United States and other countries and may not be used without written permission. All other trademarks are the property of their respective owners. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. is not associated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book.

Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. No warranty may be created or extended by sales representatives or written sales materials. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for your situation. You should consult with a professional where appropriate. Further, readers should be aware that websites listed in this work may have changed or disappeared between when this work was written and when it is read. Neither the publisher nor authors shall be liable for any loss of profit or any other commercial damages, including but not limited to special, incidental, consequential, or other damages.

For general information on our other products and services or for technical support, please contact our Customer Care Department within the United States at (800) 762-2974, outside the United States at (317) 572-3993 or fax (317) 572-4002.

Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic formats. For more information about Wiley products, visit our web site at www.wiley.com.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data:

ISBN 9781394273966 (cloth)ISBN 9781394273973 (epub)ISBN 9781394273980 (epDF)

Cover Design: WileyCover Images: © 7AM/Adobe Stock,© Fotograf/Adobe StockAuthor Photo: Courtesy of Jonathan Young

With love to my dad and my kids:

You always inspire me

Introduction

I AM A passionate fan of social networking. I love its dazzling tech at our fingertips allowing us to share our lives anywhere, anytime. As one of the earliest founders in this remarkable communication revolution, I found it exhilarating to participate in the movement bringing it to life.

But my love comes with a caveat. The original vision and execution of social networking were based on an enchanting premise. Geographic distances and technology limits were eliminated. We stayed connected with friends and family in exciting and enriching new ways. An added bonus was the ability to expand our friend circles, join like-minded communities, and explore novel interests.

In its brilliant ascent, social media was leading us toward a more compassionate and connected world. Uh-oh—did we take a wrong turn somewhere?

Today, Big Tech is driving us, our kids, and society mad. The current genre of social media is a far cry from its birthright. We have a crisis on our hands, and most of us know it. We feel small and unprotected. Tech giants rule with impunity. We’re trapped in a distorted landscape, pawns of their overt and nefarious manipulations. Here’s a sobering stat: A Pew Research survey in 2024 found that “about two-thirds of Americans, 64%, said they think social media is bad for democracy.”1

It’s easy to think we’re in uncharted territory. But the perpetrations of Big Tech—manipulations, monopolies, and profits at all costs—aren’t necessarily new. There are striking parallels in Big Agriculture and Big Energy, and valuable lessons to glean.

Get ready for a fascinating read that will keep you jaw-dropped, incredulous, and chuckling along with the book’s reveals.

Together, we’ll embark on a journey to discover an authentic, uplifting, and achievable transformation of social media and Big Tech. This is the game plan for an epic reboot. What would social media look like if it nourished our critical thinking, mental health, privacy, civil discourse, and democracy? Is that even possible? Stay tuned.

This book is for all of us—from the curious and uninitiated, to casual and heavy users of social media, to parents and teachers, to techies and entrepreneurs, to investors and elected officials. Everyone is affected by Big Tech, and everyone is part of the solution.

It’s time for velocity. What we need is insight, understanding, and an implementable plan to catapult forward. How do we get there? By the end of this book, you’ll know the answers.

In your hands is the framework.

1My Adventures in Web1 and Web2: The Rise of Surveillance Capitalism

I WAS EARLY, but I wasn’t the first. Social media was born in the late 1990s. A handful of Web entrepreneurs were tinkering, independent of each other. It was a classic hundredth-monkey effect.

In 1997, my family gathered from many points for a vacation in Stanley, Idaho—population, 110. It’s a beautiful place. The landscape near the Sawtooth Mountains is idyllic both for being together and for solitary enlightenment. Perfect for expansive thinking.

Hiking around pristine Redfish Lake, the conversation was completely unintended. My 10-year-old nephew, Justin, and I fell far behind our family members. We were chattering about using the still-newfangled Web to keep us all together. Over 25 years ago, email was already antiquated and notable for its visceral void. Web-based communication tech was in its infancy. It started like this: “Uncle Markie, wouldn’t it be great if we could …”

Ten minutes into our conversation, I was overtaken by a tingling sensation, an awareness. The words jumped off my tongue. “Justin, I am going to start a company to do this, and I’m going to give you 10% of whatever I own.”

Game on.

At dinner that night with our extended family, we imagineered, taking notes on a couple of napkins about what we wanted to share online: photo albums, chats, discussions, address books, recipes, a family newspaper, a calendar, wish lists, birthday reminders, and more.

This was Web1, as it is now known. There was plenty of capital available. The internet horse was out of the barn and everyone wanted to hitch a ride—designers, engineers, marketers, executives, you name it. Web1 had its own singularity—everyone was focused on serving the end users. No one was yet enamored with their data, or algorithmic manipulation of the ads they were served, or with their newsfeeds and purchases. Eyeballs were the valued commodity; revenue models and monetization would follow later. Web1 was labeled the “New Economy.”

It was classic entrepreneurialism. In those days, there was no LinkedIn or Indeed—I placed ads in the Albuquerque Journal’s help wanted section and interviewed candidates at my kitchen table. My 1,445-square-foot home became company headquarters. Today, software engineers are everywhere in the world. At that time, there were hardly any engineers or graphic designers experienced with Web applications. Salt that with the way people accessed the Web, via dial-up. Efficiency in programming was paramount, as most sites loaded slower than pouring molasses, and many not at all. The first graphic designer I hired was well established and highly regarded. His designs were beautiful. But his Web pages wouldn’t load.

In a stroke of luck, the State of New Mexico gave my just-birthed company a $300,000 grant to remain in the state. At the hearing to consider my grant request, they first denied it—then the chair, Mr. Garcia, pulled the committee into a back room. Moments later, they reemerged.

“Mr. Weinstein,” Mr. Garcia began, “several years ago, we rejected Bill Gates’s application and he left the state …”

Gates’s dad, I later learned, beckoned him to come home to Seattle for parental funding.

Mr. Garcia continued, “After reconsideration, we are approving your request for a $300,000 In-Plant Training Grant.”

Wow! Thank you, Mr. Gates. The state also provided and subsidized sweet offices in Albuquerque’s newly built Science and Technology Park and added a custom-built server room. We were off to the races.

We grew to about 70 team members in all. Along the way, we partnered with Sun Microsystems and Oracle to build the largest commercial installation of servers in New Mexico. Every weekend we ran a full-page print ad in USA Today, promoting this newfangled social Web experience. There were billboards touting our sites. In 1998, traditional marketing techniques were the best way to reach and attract users. Our flagships, Superfamily.com and SuperFriends.com, made PC Magazine’s “Top 100 Sites” list three years in a row.1 It was one of the most prestigious accolades for websites at the time. We were participating in a new paradigm, “Community Portals” (later to be called “Social Networks”).

Web1’s colossal fall from favor with investors in 2001 hailed its curtain call. Virtually overnight, what had been an easily accessible pot of investor capital, limited only by how much dilution was palatable, dried up. Understandably, Web1’s “New Economy,” based on a site’s number of users and their anticipated future monetization rather than the tried-and-true measurement of actual revenue, profit, and loss, fell from grace. Investors panicked before seeing their companies achieve financial success. The stampede was brutal. The sudden dearth of funding caused massive failures, though everyone had bought into the paradigm. A historical event, the dot-com bubble, burst, and I was caught in the middle.

Egg on my face, guilty as charged—as I had bought into the eyeballs-first mantra and believed it was the only way to encourage hesitant newbies to step into the Web. Paradoxically, the phoenix rising—Web2 —professed the same mantra, but with a new twist: Surveillance Capitalism. Personal data analytics and targeted marketing would resolve the revenue conundrum, manipulate those eyeballs, and make profits pop like never before.

Looking back, it’s both curious and foretelling. There was a purity of purpose in Web1, the dedicated focus on serving the customer, in this case the “user,” the leveraging of rapidly iterating communication technologies. What I and a handful of other entrepreneurs were creating in Web1 is now known as “personal social networking.” Today, over 5 billion people participate in this paradigm.2 In Web2, it would become one of the most successful business models in history.

Web2: The Rise of Surveillance Capitalism

“Privacy No Longer a Social Norm, Says Facebook Founder.”3 The headline in The Guardian blared on January 10, 2010.

My mouth opened, jaw-dropped, as I witnessed Mark Zuckerberg make this bold declaration at the Crunchie Awards in San Francisco, a ceremony then widely covered in the press. Social media was invented to serve people, not spy on them. His thought process and arrogance bewildered me. His wallet was more important than the fundamental human right to privacy?

Today and for most of the 21st century, we’ve been participating in the greatest socioeconomic experiment in human history. It’s called Surveillance Capitalism. This is the elephant in every room of our lives. Surveillance Capitalism is the modern-day business model in which everything we do—morning, day, and night—is tracked, analyzed, and monetized.

Our personal information is packaged into datasets shared and sold in a hidden ecosystem of massive data companies. These data brokers generate hundreds of billions of dollars per year by collecting our data from Web and social media companies, credit card networks, retailers, and other entities. They then provide access or sell it to whomever desires it.4 Our data is then used to target and manipulate us—by advertisers, marketers, social media companies, politicians, governments, and every other person or entity that aims their dart directly at us. Our independent thoughts, critical thinking, and privacy are becoming relics of the past.

In the past two decades, the rise of Big Tech has placed human beings under nearly constant surveillance. Our phones, computers, Alexa, the Web, and everything we do online, everywhere we go, is all being tracked. Our relationships, our purchases, our finances, our health issues, our politics, our religious beliefs, our diets—you name it. It’s estimated that, by the time we reach the age of 13, about 72 million data points on each of us have been collected.5 This number is stunning and hard to grasp, but true. This data is monetized by commercial interests, stolen by hackers, and shared with governments.

How the heck did we get here? Courtesy of the premise and promise of Web2. In the ashes of Web1, companies like Google and Facebook arose and discovered they could reap more profits by spying on us under the guise of serving us. This solved the conundrum of Web1, and suddenly revenue flowed handsomely from their new targeting business models. Other companies quickly followed suit, spreading the Surveillance Capitalism business model across the world.

Today, these entities know more about us than our own mothers do. They know everywhere we go, every friend and family member, every search, every website, every health issue, every financial transaction, every fantasy and fear that we research. All these private moments are broadcast directly into the global data ecosystem. As Yael Eisenstat, former CIA analyst, diplomat, and Facebook employee, said in 2019, “Facebook knows you better than the CIA ever will. Facebook knows more about you than you know about yourself.”6

So, somebody out there is collecting all your private information. Is that such a bad thing? Yes, it is. If you want to see where Surveillance Capitalism is headed, let’s take a look at what is going on right now in China.

China’s “social credit system” tracks its citizens and imposes punishments for what it deems to be undesirable behaviors, like playing too many video games, jaywalking, and “frivolous spending.”7 Penalties include blocking citizens from getting good jobs and preventing their kids from attending top schools. And Chinese citizens have even been thrown in jail for making jokes and sharing satirical memes8 about the authorities in “private” social media chat groups.

With the help of AI, Surveillance Capitalist companies employ psychologists and data scientists to analyze and covertly manipulate our emotions, thoughts, votes, and purchases. This is a good career path if you enjoy snooping—they’re always hiring. The companies then sell access to our eyes and newsfeeds to the highest bidder. They keep us addicted to our phones, iPads, laptops, … The more time we spend on their platforms, the more data they can extract from us, and the more they can invite any paying customer to take aim at us so they can win the game.

With their deep knowledge of our psyches and emotions, the social media giants even deliberately serve us polarizing content. Why? Because outrage keeps us glued to our screens.

At the time of Zuckerberg’s declaration, my life was cozy and bountiful, but I couldn’t ignore the nagging in my soul. This was bigger than all of us; it was about the future—ours, our kids’, and the world’s.

▄ ▄ ▄

I changed my life once more, relocating in 2011 to Mountain View, California, the heart of Silicon Valley. This time, Albuquerque would not suffice for fundraising; California investors and venture capitalists (VCs) were no longer keen to get on airplanes to vet a tantalizing proposition. Their funds and countless deals were now right in their neighborhoods.

What started with focus groups in my dining room in Albuquerque and then a multiyear beta project in Sunnyvale became the Facebook alternative, MeWe. Luminaries joined MeWe’s Advisory Board, including Tim Berners-Lee, the inventor of the Web;9 Raj Sisodia, cofounder of the Conscious Capitalism movement;10 Sherry Turkle, an MIT academic and leader in tech ethics;11 and Steve “Woz” Wozniak, cofounder of Apple.12

The site and app launched in 2016, built purposefully to solve the issues perpetrated by the Surveillance Capitalists dominating social media. MeWe provided the industry’s first Privacy Bill of Rights13 for its users. While carefully protecting civil discourse, under my leadership MeWe also had no ads, no targeting, no data harvesting, no boosted content, and no newsfeed manipulation. Deploying a customer-centric freemium model, revenue came from premium features, in-app purchases, and subscriptions.

Talk about another exhilarating ride! Curiously, the promise of VC funding failed to materialize—something about having landed in Facebook’s backyard with a clear message that MeWe intended to be a direct full-featured competitor. Apps that were getting funded were more discreet, and most were launched as one-trick ponies, like Snapchat, Twitter/X, WhatsApp, and Instagram. They had unique and slim features that went viral quickly, allowing their teams to raise millions while not encroaching on Facebook’s turf.

This freezeout caused plenty of consternation and challenges but a simultaneous freedom from VC oversight and their likely dilution of MeWe’s principles. Without large, eight-figure inflows, investment capital—millions of it—was provided by a myriad of qualified investors who understood MeWe’s raison d’être.

I traveled the globe—from the USA to Asia to Europe to Latin America—to secure the company’s funding. So much for my geographical location choice to avoid just that. Funds raised were consistently deployed to stay competitive with Facebook and with the constant flow of new features and fads (1:1 communication, private and open groups, disappearing content, stories, journals, custom memes, dual camera videos, live video calls, voice memos, encrypted chat, personal cloud, etc.).

During my time there, the company won numerous accolades including being named a 2016 Start-Up of the Year Finalist for “Innovative World Technology” at SXSW; a 2019 Best Entrepreneurial Company in America by Entrepreneur Magazine; and a 2020 Most Innovative Social Media Company by Fast Company.

It became a battle of the Goliaths versus the Davids (with Goliaths consistently winning) as mainstream networks peaked and new upstarts failed. Some gained outstanding traction, notably WhatsApp and Instagram. Facebook gobbled them up among countless acquisitions. All others failed and were squashed. In the same time window, the data industry became the King Kong of it all.

To my knowledge, MeWe is one of the only apps in Web history to achieve 20 million registered users and millions of dollars in revenue without influencers, a marketing budget, or VC funds. Perhaps the numbers would have been closer to 500 million users or more if Facebook hadn’t stifled the good word about MeWe.

In federal court on August 19, 2021, the United States Federal Trade Commission (FTC) filed its amended antitrust complaint,14 stating that Facebook (Meta’s flagship) had a monopoly on the “personal social networking” market. According to the definition in the brief, a personal social network is an online platform for users to stay in touch with “personal connections in a shared social space.”

As stated in the brief, MeWe and Snapchat were the only two direct competitors to Facebook left standing. All other personal social network upstarts had either gone out of business or been acquired by Meta. None of us had upended the emperor.

Surveillance Capitalism has overrun common sense. Fundamental human principles are in peril. In its current state, Web2 is not capable of alleviating its cancers.

I left my day job at MeWe on Independence Day, 2022. New investors and a new executive team there are focused on its success. MeWe is not the solution to this Gordian knot. My mission when I started MeWe was to restore the privacy protections, authenticity, and connectivity that social media was born with. In the past decade, the problems with social media have become much bigger than any single company can solve. The blossoming of issues around mental health, election interference, biased censorship, exploiting kids, boosting, bots, trolls, and much more necessitate a different path forward. A revolutionary framework is required.

2Uncanny Parallels: Big Ag, Big Energy, Big Tech

TO WRAP OUR minds around the Web and its trajectory, it’s helpful to observe the patterns of other industries. For our purposes, let’s examine food, energy, and the Web. What do these three disparate categories have in common? Each has its own unique issues and peculiarities, but at a high level the parallels are striking, their patterns uncannily similar.

All three are essential in modern society and today are dominated by a handful of monopolistic corporations. Eerie and omnipresent, they have unprecedented power over our lives. Big Ag controls what foods we eat; Big Energy controls what energy we use; Big Tech controls what information we consume.

In the Beginning

One of the challenges in this era of Big Tech is the lightning pace at which innovation and new technologies are presented to us. This speed is historically unprecedented. In the past, a game-changing innovation such as the printing press lasted a few centuries before it was superseded. Social networking was invented in the 1990s and gained mainstream popularity in the 2000s. (Remember MySpace?) Today, over 90% of Americans1 and 60% of the entire human population2 actively use social media. In the blink of an eye, it has overtaken our lives and the world.

Concurrent with the tech revolution, there are promising grassroots movements afoot to rectify the problems of Big Ag and Big Energy. There are rapidly amplifying voices for a parallel movement to address the perils of Big Tech. Let’s take a closer look at these parallels. What are their foundations? And how did we get here?

Big Ag: The Seismic Shift

Around 10,000 years ago, humans first began to develop agriculture and animal domestication. This was a seismic shift from the nomadic hunter-gatherer lifestyle practiced by our ancestors since the dawn of humanity. From this inflection point emerged the first sedentary tribes, villages, cities, and advanced civilizations. Farming, agriculture, and animal domestication concurrently developed to feed and nourish these growing communities. Yet, over time, advances in technology and new economic models developed that distorted these practices.

For our purposes, let’s fast-forward to the mid-20th century. Prior to World War II, there was no widespread industrial farming, also known today as “factory farming.” Farms in America were small scale and usually family owned. The stores selling food produced by these farms were typically local mom-and-pops. After World War II, massive, industrialized farms (what became known as “Big Ag”) began to arise in tandem with major food retailers (“Big Food”).3 They evolved together to form today’s “seed-to-retail-sale” distribution lockstep.

Big Energy: Harnessing Earth’s Resources

For thousands of years, ancient people used coal, natural gas, and oil for heating, cooking, and lighting.4 More than 2,000 years ago, advancing civilizations then began using water wheels to harness the energy of flowing rivers (including the Roman Empire, ancient Egypt, India, and China). Believed to be the first method of mechanical energy to replace the work of people or animals, water wheels were used to irrigate crops, grind grain, and provide drinking water to villages.5 Next up, windmills came into play over 1,000 years ago. They were used in Europe, the Middle East, India, and China to pump water, grind grain, and assist with food production.6

That’s enough ancient history. Fast-forward to the Industrial Revolution of the 1800s, when the utilization of fossil fuels like coal and petroleum to power our societies first became widespread. Coal became a critical resource to power steam engines and other machinery. America’s first commercial natural gas well was drilled in New York in 1821,7 and the first commercial oil well was drilled in Pennsylvania in 1859.8 Since then, fossil fuels have become the primary source of energy across the world, providing us with heat, electricity, and fuel for transportation. While these power sources were originally intended to help us prosper, they’ve had the unintended consequence of devastating our environment, polluting the air we breathe and the water we drink.

During this period of expansion in the 1800s and early 1900s, there were some who sought alternative paths. In 1884, Charles Fritts, an American inventor, installed the world’s first rooftop solar array in New York.9 This was just two years after Thomas Edison launched the world’s first commercial coal plant. A couple decades later, in the early 1900s, visionary scientist and inventor Nikola Tesla made plans for the mass commercial utilization of renewable energy. He envisioned a world with electricity generated via solar, wind, and geothermal technologies.10

However, fossil fuels were much more accessible and affordable. They won the day and that early battle, and triggered an unrelenting domino effect. As the 20th century progressed, the energy sector became dominated by a small group of oil and gas conglomerates and utility giants, now known as “Big Energy.”

Big Tech: The Birth of the Web and Social Media

The Web and social media didn’t emerge until after Seinfeld was on the air, yet its precursors were born centuries earlier. Even before Shakespeare. The widespread distribution of targeted information informing and manipulating our philosophical and political thoughts, along with our snake oil purchase decisions, started 600 years ago. The invention of the printing press in 143611 was the sea change that launched the Information Revolution. This inflection point of innovation spread throughout the world over a few centuries. Its reign was joined by significantly advancing inventions in just the last 180 years. Examples abound, including photography, telegrams, telephones, film and video, fax machines, and cellphones.

Then came the Web in 1989, eclipsing all that came before. The world went from disjointed to utterly connected in a heartbeat. Like the printing press in its day, this technology is far ahead of any sense or sensibility we have regarding its impact on our lives, minds, and well-being. And hence, a conundrum for regulatory oversight.

While the Web was originally a bridge for communication between university scientists, Web inventor Tim Berners-Lee and his team saw far greater potential. They advocated for the underlying code of the Web to be available to all, free forever.12 What Berners-Lee didn’t realize was that his invention would become the most powerful medium for expanding communication and knowledge in the history of the world. For his unintended stroke of genius, he was knighted by Queen Elizabeth II in 2004.13

Inspired by the spirit of Berners-Lee’s vision for the Web, early social networks were designed to serve their users as cherished customers. Friends, family, and like-minded folks came together through the magic of this newfangled (and remarkable at the time) communication tech. The wrinkle is that today’s lightning pace of innovation partners perfectly with monopolistic capitalist forces. Uh-oh.

Monopolistic Consolidation

So, what has happened? The idealistic foundations of farming, energy, and the Web were overtaken by natural human greed. Over time, this avarice has led to powerful and destructive monopolies. The end results across these sectors bear uncanny similarities.

Big Ag: Factory Farming

Since World War II and the birth of industrialized factory farming, extreme consolidation has occurred across all parts of the food industry. The next time you buy steaks or hamburgers (if you’re a meat eater) at the grocery store in the United States, there’s more than a good chance they will come from JBS, Tyson, Marfrig, or Cargill. From 1982 to now, these four companies (including their subsidiaries) increased their market control of beef production from about 40% to over 80%.14 Just four conglomerates also control nearly 70% of all pork and over 50% of all poultry production in America.15 Similarly, the five largest seed suppliers increased their global market share from about 20% in 1994 to over 60% today.16

Giant conglomerates control virtually every aspect of the food production process, from selling feed to farmers to packaging meat and poultry for supermarkets. This situation has led to significantly lower pay for farmers, fewer choices and lower-quality foods for us consumers, and skyrocketing profits for Big Ag monopolies. Bill Bullard, CEO of the Ranchers-Cattlemen Action Legal Fund, stated, “We’ve never witnessed this level of concentration in the history of our industry. This situation is urgent.”17

Big Energy: Legal Monopolies

Big Energy includes the major oil and gas conglomerates that fuel most of our freight trains, trucks, ships, airplanes, and gas-powered cars. It also includes the utility giants that supply electricity to our offices, factories, homes, stores, and electric cars.

Let’s start with a glimpse at oil and gas. Hello, Model T, good-bye, horse and buggy. In the early 20th century, Standard Oil quickly rose to dominate the booming oil market, eventually owning 90% of all oil production in America.18