14,39 €

Mehr erfahren.

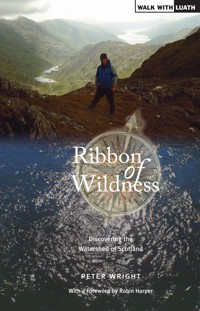

- Herausgeber: Luath Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Serie: Ribbon of Wildness

- Sprache: Englisch

The Watershed of Scotland is a line that separates east from west; that divides those river basin areas which drain towards the North Sea on the one hand, and those which flow west into the Atlantic Ocean on the other. It's a line that meanders from Peel Fell on the English border all the way to the top at Duncansby Head, near John O'Groats - over 745 miles, through almost every kind of terrain. The Watershed follows the high ground, and offers wide vistas down almost every major river valley, towards towns and communities, into the heartlands of Scotland. Ribbon of Wildness provides a vivid introduction to this geographic and landscape feature, which has hitherto been largely unknown. The rock, bog, forest, moor and mountain are all testament to The Watershed's richly varied natural state. The evolving kaleidoscope of changing vistas, wide panoramas, ever present wildlife, and the vagaries of the weather, are delightfully described on this great journey of discovery. Along the route of the Watershed the general emptiness of the journey will strike the walker all the way, creating a unique, beautiful, spiritual dimension to the walk. BACK COVER: If you've bagged the Munros, done the Caledonian Challenge and walked the West Highland Way, this is your next conquest. The Watershed of Scotland is a line that separates east from west; that divides those river basin areas which drain towards the North Sea from those which flow west into the Atlantic Ocian. It's a line that meanders from Peel Fell on the English Border all the way to the top of Duncansby Head, near John O'Groats - over 745 miles, through almost every kind of terrain. The Watershed follows the high ground, and offers wide vistas down major river valleys, towards towns and communities, into the heartlands of Scotland. Wakj the Watershed in eight weeks. Tackle short sections over a weekend. 7 route maps. Over 30 colour photographs. Ribbon of Wildness provides a vivid introduction to this geographic and landscape feature, which has hitherto been largely unknown. The rock, bog, forest, moor and mountain are all testament to the Watershed's richly varied natural state. The evolving kaleidoscope of changijg vistas, wide panoramas, ever-present wildlife, and the vagaries of the weather, are delightfully described on this great journey of discovery.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 415

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

PETER WRIGHT walked the Watershed of Scotland in 2005. It took him 64 days to cover the whole 1,200km, 745 miles, and he was struck by how much of the route went through wild land. He started to write this book as a journal of his journey, but soon began to research and find wider evidence for his observations of the wildness. He has long been interested in Scotland’s natural environment and history, having volunteered with both the John Muir Trust, and the National Trust for Scotland. He has worked for some 20 years developing the Duke of Edinburgh Award in the Edinburgh area, for which he received the MBE. The National Trust for Scotland presented him with the George Waterston Memorial Award for outstanding voluntary commitment. Peter was instrumental in establishing The Green Team, and is now its honorary Patron.

Ribbon of Wildnessgives a vivid introduction to this hitherto largely unknown geographic feature.

THE GEOGRAPHER, Royal Scottish Geographical Society

[Ribbon of Wildness]is something truly special and an immense celebration of the best of Scottish landscape.

RORY SYME,John Muir Trust Journal

Ribbon of Wildnesswill inspire others to view more than a few of the wondrous landscapes of Scotland whilst basking in their wildness.

SCOTTISH WILDLIFE MAGAZINE, Scottish Wildlife Trust

A remarkable and incredible journey which others will most surely want to tackle.

THE HOUR, STV

Absorbing account of a strenuous and meandering walk from Peel Fell on the Border to Duncansby Head, Caithness – all without crossing a stream.

SCOTLAND IN TRUST MAGAZINE,National Trust For Scotland

John Muir would have been proud of this tremendous wild journey. Scotland’s watershed is a remarkable feature of our country, and unites wild places; both familiar and remote. This unique Ribbon of Wildness leads us on an insightful exploration of our precious wilder land and its people.

I HUTCHISON, Chairman, The John Muir Trust

Ribbon of Wildness

Discovering the Watershed of Scotland

PETER WRIGHT

LuathPress Limited

EDINBURGH

www.luath.co.uk

First published 2010

Reprinted with minor changes 2011

Reprinted 2012

ISBN (print): 978 1906817 45 9

eBook 2013

ISBN (eBook): 978-1-909912-22-9

Maps by Jim Lewis

The author’s right to be identified as author of this book under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 has been asserted.

© Peter Wright 2010

As we approach 2014, the centenary of the death of John Muir, this book is dedicated to his memory and the inspirational legacy he has left for us to enjoy.

Contents

Map

Foreword Robin Harper MSP

Preface

Acknowledgements

CHAPTER ONE Introduction

CHAPTER TWO The Reiver March

CHAPTER THREE The Laich March

CHAPTER FOUR The Heartland March

CHAPTER FIVE The Moine March

CHAPTER SIX The Northland March

CHAPTER SEVEN Conclusion

APPENDICES

ONE Munros and Corbetts on the Watershed

TWO Key Areas with Conservation and Biodiversity Objectives

THREE Agencies and Organisations with an Active Conservation or Biodiversity Role

FOUR Land Classification and Capability for Agriculture on the Watershed

Bibliography

Map of Scotland showing the Watershed, North Sea and Atlantic Ocean

Foreword

IT IS WITH THE GREATEST of pleasure that I sat down to write a few words by way of introduction to this highly original work. Peter has dedicated most of his working life to encouraging young people to get into the outdoors, not least through his huge contribution to the development of the Duke of Edinburgh’s Award in Scotland, his creation of The Green Team, and his part in the development of the John Muir Award. Ever since Rev A.E. Robertson climbed all of the 238 then known mountains in Scotland over 3,000 feet, we have been more than mildly obsessed with seeing the hills as simply a challenge in themselves – an environment to be conquered.

Peter’s approach is more leisurely and thoughtful, and provides a very distinctive view of a Scotland whose history, politics, geography and landscapes have been subtly shaped on either side of the windy ridges which sweep northwards all the way from the Lowlands to Caithness.

To the west, the Gaels, Norsemen and the Earls of Orkney, to the east the Picts and the Britons, and to the south the Romans, Angles and Saxons; these ridges kept cultures apart and slowed the rate of assimilation in such a way that the spirit, the cultural song of these diverse interests, survives in so many ways that add to the present richness and value of our heritage.

You can stride with Peter on this journey, on your own ribbon of wildness and appreciate the full richness of the landscapes that fall away on either side of it. You can experience the beauty and the contrasts between the wetter west with its lochs, woods and rocky shorelines, and the softer straths of the east, and reflect on how these landscapes shaped our history, psyche, and our cultures down the centuries. You will be moved; it will undoubtedly raise your spirits.

Thank you Peter for a gentle view, your perception of our landscapes shaped by a journey, a thoughtful stroll rather than just a physical challenge; an engagement with what lies beside and behind us, as well as that which lies ahead, a truly original and three-dimensional view.

Robin HarperMSP, 2010

Preface

Ribbon of Wildnesshas been well received across a broad spectrum of interests throughout Scotland. Rapid sales, widespread invitations to give talks and take part in events, positive reviews and comments, growing evidence that it is beginning to inspire some pretty ambitious plans, and so much more, are all testament to the book’s popular appeal. This is all the more pleasing given that it had not really been in my mind to write a book about the Watershed when I undertook that epic walk in 2005. But the notion of a ribbon of wildness somehow emerged as I contemplated all of the landscapes I was experiencing, and as I followed a line created simply by the hand of nature, it became evident that there was something to write about. If the Watershed was, as I suggest, ‘the sleeping giant of the Scottish landscape’, it has most assuredly begun to be roused – or opened one eye, at least.

What pleases me most is, of course, the evidence that the Watershed is beginning to be appreciated, understood and valued, and is providing inspiration simply by what it is – largely continuous wildness. That prevailing characteristic and quality on such an immense scale is special, unique even.Ribbon of Wildness: Discovering the Watershed of Scotlandhas added a truly new dimension to our understanding and potential enjoyment of Scotland’s countryside through this distinctive ribbon of hill, mountain, moor, bog and forest. I have no doubt that this reprint, which contains a few necessary updates, corrections, and perhaps the occasional improvement to the text, will be widely sought and give added energy to the plans that are taking shape in many quarters.

In the few years since I walked and then wrote about the Watershed, there has been one major and all too rapidly growing imposition on our landscapes. As I talk to people the length of the land, it is clear that there is genuine alarm at the seemingly inexorable spread of wind farms – especially in the more prominent locations of ridge and skyline. If I was somewhat ambivalent about the issue in the first printing ofRibbon of Wildness, I take a new stance in this one. Wind farms are a blot on the wildness of the Watershed, and should therefore be strenuously opposed on and around it. To those community groups that have the task of presenting a compelling case to conservetheirbit of wildness, I gladly add my voice. I very much hope that this book and all that it represents will add strength to these campaigns.

In the first year since its publication,Ribbon of Wildnesshas made a difference and had some worthwhile impact. It is a tantalising thought to ponder where all this will be in five years time! Patience must however prevail and, in the meantime, do enjoy all that is within these pages.

Peter Wright,2011

Acknowledgements

THE GENESIS OFRibbon of Wildnesslay in a long and largely solo walk, but many people – both friends and strangers – helped along the way and the whole experience was undoubtedly enriched by their generous interest and support. The process of research for the book was similarly helped in no small measure by advice that was freely given, and the enthusiasm of the many people that I consulted. The list of all those who have helped would be a lengthy one, and might well run the risk of appearing as a litany of names and interests. And there would be the danger of causing offence by inadvertently omitting some who had in good faith been unstinting with their contribution. So the prudent, but no less sincere course, is to record an all-embracing ‘thank-you’, with my genuine gratitude to each and every one who played a part in shaping what appears here in this book; your help is warmly appreciated.

I make one exception, though. My family has been very understanding, and shown a lot of patience, as I have become somewhat engrossed in this great interest. So I want them to know that their support is not received lightly; I am immensely grateful.

CHAPTER ONE

Introduction

THE GREAT ENVIRONMENTALIST John Muir (1838–1914), in summing up his introduction to nature wrote, ‘When I was a boy in Scotland, I was fond of everything that was wild, and all my life I’ve been growing fonder and fonder of wild places and wild creatures’.This pithy observation will have struck a clear chord with countless people in Scotland and beyond, as it echoes down the years to the present day. For many of us it is the wild places, and their spirit of wildness, which give the defining inspirational experiences; we are at one with the immense quality and diversity of our surrounding landscapes. With Muir, we grow ever fonder of Nature and her wildness.

And there is delight for us in the detail as well as the grandeur – moments of pleasure to be had in coming upon a single wild flower, or the enchanting sound of the skylark on the moor, every bit as much as the bigger landscape and wide mountain vistas. We are in its thrall.

Perhaps it was simply the desire to tackle a really challenging journey that prompted my interest in this venture, for having done a number of coast-to-coasts, and other such walks, I developed an appetite for more. Some of the books about long walks that I had read had prompted me to think of something ambitious of my own, and a wider passion for Scottish landscape, combined to pose a quest for the largely unknown. It was somewhere amongst this jumble of tantalising imaginings, that I conceived that Scotland must have a watershed. One of the few subjects that I had any great interest in at school was geography, and that interest had lingered down the years, so the idea of a watershed (which I will expand on shortly), seemed appealing. Thus, I got the necessary research underway, and started planning for what would be a logistical challenge in itself.

So, what started as a mental exercise, turned into a physical epic, and has become my great passion – for reasons that will most surely become evident. Writing a book about it, or more precisely, about what I discovered over 64 days of walking and my subsequent research, has all taken me down a track that I never envisaged. I had thought that simply walking it would be enough, but something even bigger, every bit as compelling and immensely enriching has grown from my challenge.

It is my great privilege to share some of this experience with those who care to readRibbon of Wildness,and to discover why I have chosen this title. They may well see Scotland, her landscapes, our interaction with them, in an entirely new light. They may just see the possibility of a new challenge, and all the delights that this could bring.

To start with, we must look briefly at some of the forces and timescales that created the Scotland we know and value today. Here we find that this landform evolved like a vast three dimensional jigsaw puzzle, with a number of the pieces coming together having variously drifted half way across the face of the planet. Scotland is the sum of its parts, and took a great many millions of years to develop. The oldest rocks here are amongst some of the most ancient on earth, at over 4,000 million years. They, along with their younger neighbours, were at times submerged under the oceans, or drifted as the sands of the hot deserts, or lay as the floor of vast swamps. They were then either thrust upwards by forces that are almost beyond comprehension, or were subjected to great heat or severe cold. They were compressed by the immense weight of overlying layers of rock, or the ice cap that lay on top, and was a mile or more deep. In places volcanic action further mixed the chronology of the different strata that make up the layers. Younger rock poured out on top of much older, with almost cataclysmic compression. The force of colliding tectonic plates caused further distortion and twisting, and in time great cracks appeared and sliced across the crust. The land on either side of these fault lines experienced further change, with the two sides moving sideways and very slowly in opposite directions. In some locations the immense pressures involved in this distortion of the earth’s crust caused one side of the fault to over-ride the other, forcing the lower level down into the earth’s mantle, and thus creating a geological conundrum. Fire, water, movement, time, fracture and eruption are just some of the direct causes of what lies beneath, but are fundamental to the landscape of Scotland we see today.

That is not all, for a number of Ice-Ages, the most recent ending only 11,000 years ago, left their mark. Having ground down and removed the surface rocks, they eroded ever deeper into the crust. Thousands of metres of rock were removed in the process and then as the ice finally melted sea levels rose; as with a great sigh of relief parts of the land rose too, when the great weight of the ice, which had borne down upon it, finally disappeared. Two thirds of what became Scotland almost separated from the rest and would have become another island, but the tide turned, and the shape of the land that we know and love was established.

Stone Saga

Gradually the land was colonised by plants, birds and animals which migrated northwards across the land bridge that then linked us to mainland Europe. Gradually too our landscape took on a fertile living mantle, and the round of the seasons established a perceptible pattern from year to year. But climate change – yes, there is nothing new about that – heralded colder and wetter conditions, which had a lasting impact. We can still see evidence of this today, in the large areas of peat that started to form during this period. And finally, the actions of man over the last ten or more millennia, have left their mark as we have used and abused the resources of nature at our disposal. So what we have today in our landscapes is the product of a multi-dimensional geological process, with the impact of climate changes and the lasting affects of our own efforts. James Hutton (1726–97), the founding father of much of our geological understanding, in describing geological processes saw ‘... no sign of a beginning, and no sign of an end.’ A contemporary of his wrote ‘... we grew giddy as we gazed into the abyss of time.’ This helps to put our own relative insignificance on the face of the earth into some perspective, but as we shall see our actions have probably had a greater effect than our brief tenure might otherwise justify.

How do we make sense of this rich tapestry – our landscape? Well, the best way to start is simple and practical, with a visit to the higher ground; for it is from some elevated vantage point that the patterns and variety of the countryside becomes clear. From the higher ground we can see the valleys, lochs, hills, moors, fields, distant coast and islands unfold into wide panoramas which expand outwards to the horizon. The Watershed is on the higher ground, it is the continuous spine of Scotland, and it is from this elevation that our great country can be viewed and appreciated, in a novel and immensely revealing way. This book invites you to make a journey of discovery of much that this geographic feature has to offer. It has been obscure until recently, but certainly now merits wider appreciation; it is a sleeping giant that begs to be woken by popular interest and involvement. And the word giant is apt, for the Watershed is on a grand scale at some 1,200 kilometres from end to end, and an average elevation of around 450 metres above sea level. It is consistently on the higher ground.

It will be argued that it is a unique linear geographic feature, that its distinctive quality is that it is relatively wild, or wilder throughout – that there can be no other single entity in the physical geography of Scotland that largely maintains this character on such an epic scale. The Watershed truly is an artery of nature, which flows all the way from Peel Fell on the border with England, to distant Duncansby Head, overlooking the waters of the Pentland Firth, with the Orkney Islands beyond.

The description of what the Watershed is that establishes its linear location is not complicated: any map of Scotland shows that its landform faces in two distinct directions: east towards the North Sea on the one hand, and west to the Atlantic Ocean on the other.

Now imagine that you are a raindrop about to descend on Scotland: whether you end up in that ocean or that sea will clearly be determined by where you land, and the Watershed is the defining line. And although it is a rather rambling line, it is none the less definitive. If, as that raindrop, you land to the east of the line, then by bog, burn and river, you are bound for the North Sea, and should you land on the other side of that line, then you are westward, and Atlantic bound.

This simple definition does require further examination; some explanation is called for.

As recently as 6,000 years ago, before sea levels rose to their current levels, what we now call mainland Britain was physically part of Europe, with a large area of land called Doggerland filling the English Channel and the southern part of the North Sea. At the northern end of the UK, what later became the Orkney Islands formed a peninsula at the upper extremity of this very different looking landmass. But then, as now, there was a distinct body of water to the east, which was to become recognised as the North Sea, and all of the water to the west of this was the Atlantic Ocean, or connected directly to it. Thus what we now call Scotland has, since at least the end of the last Ice-Age, had a clear east-west divide, and that line of demarcation has since extended northwards through Orkney and beyond, to the Shetland Islands. This has been critical in helping to determine the northern terminus of the Watershed on the mainland of Scotland.

Each major part of the Watershed has a distinctive geological and physical character, and the main fault-lines form the points of transition from one to the other. It is largely from this that each section derives its’ particular landscape type and special qualities.

There have been a small number of people who have walked versions of the Watershed, most notably Dave Hewitt. His excellent book on his trek entitledWalking theWatershed,set the northern end at Cape Wrath – the top left hand corner. Whilst his account of his journey makes an excellent read, and has a compelling narrative about what can only be described as a very demanding continuous walk, I differ on the significance of where the Watershed ends in the north. He was, I believe, enticed by the promise of including Foinaven in his journey, and hence heading towards the wilds of Cape Wrath. However, I would argue that there is only one geographically correct Watershed, and the North Sea-Atlantic Ocean divide is the simple key to it. This very clearly brings both of the island groups of Orkney and Shetland into the picture. The body of water off the short north coast of Scotland is most certainly part of the Atlantic Ocean. Were you to stand on the western shores of either Orkney or Shetland, and remark to yourself and your companions ‘next stop America’, your gaze would be across the Atlantic swell. Finally, the rocks from which both Caithness and Orkney are formed show geological continuity; these areas are part of the same structure. From all of this, it can be seen that the northern terminus of the geographic Watershed on the mainland is firmly anchored to Duncansby Head.

So, whilst the definition of the watershed is fairly simple, and plotting it on a map is relatively straightforward, it begs the question as to what and where are the existing geographical or cartographic references to it? The answer would appear to be that there were none; there were no maps showing the Watershed in its entirety – I could find nothing definitive. Having been unable to unearth any precise references to it, I decided to do something about this gap in our available material, and this book is the result.

Having defined what I meant by ‘the watershed’, and clarified its geographic credentials, I started with arguably the two most significant geographic organisations: The Royal Geographic Society and The Royal Scottish Geographical Society, and I drew a blank with both. Neither organisation could provide any reference to what I was looking for. I then wrote to a number of seemingly appropriate academics on the subject, and again drew similar blanks. I dug deep into the very comprehensive and contemporary publicationScotland – Encyclopaedia of Places and Landscapes(2005), but still the Watershed remained elusive. I visited the National Library of Scotland Map Library at Causewayside; still nothing! A good friend who is both a geographer and climber pointed me in the direction of Francis Groome’sOrdnance Gazetteer of Scotland(1884), and this set the quest rolling. Here I did find an unequivocal definition of the northern end – Duncansby Head.

This quest had intrigued me, not least because in this day and age, when it would seem as if everything has already been weighed, measured and counted, it was strange to find something as seemingly simple as the Watershed unaccounted for. And this became even more tantalising as the watersheds of other countries and continents are both defined and well known. In the Americas, the watersheds of both North and South are almost celebrated, and closer to home Nicholas Crane’s wonderful bookClear Waters Rising,which is about his 10,000 kilometre journey along the watershed of mainland Europe, from Cape Finisterre to Istanbul, is popularly acclaimed. These watersheds are very much on their respective maps.

It is perhaps useful at this stage to consider at what point in the development of the mapping of Scotland that the Watershed could have been plotted with any accuracy. When was it that maps had reached a sufficient degree of sophistication, with enough key information, to allow for a reasonably placed line to be drawn?

In the second century AD, Ptolemy produced a map of the British Isles for the benefit of the Roman administration, and given that much of Scotland was beyond the accepted limit of both the Roman Empire and its occupation or incursion, the map was somewhat vague as to what lay beyond their frontiers. Scotland is depicted as being orientated west to east, thus lying at right angles to England. The original of this map has been lost, but a 12th or 13th century copy survives. From this and other related references, a version was printed in the late 15th century. There are a number of recognisable features on this map including some of the major firths and rivers, but the layout and information is wholly insufficient to draw any watershed. Similarly, the Gough map of about 1360, whilst pointing Scotland correctly on its north-south axis, and showing some features that we would recognise, offers a confusing correlation of other features; it lacks a convincing overall shape. By 1546, Lilly had drawn a map which was getting much closer to the Scotland we know, but certain key features were either missing or still misplaced.

Just twenty years later, in about 1566, two maps appeared which did offer a much clearer picture in terms of shape, key features and their correlation to each other. An anonymous Italian map almost provides the necessary detail and in the right place, but it put the Great Glen crossing at the wrong end of Loch Lochy, and so fails the test. Lawrence Newell’s map, on the other hand, offers a convincing route around and between all of the key features for plotting the Watershed. Critically, it locates the Orkney Islands in exactly the right place off the far north east coast. Thus, 1566 or thereabouts is the essential date for determining the point at which map making, and the surveying techniques to go along with it, had advanced sufficiently to show most of the major rivers flowing in the correct direction, and their correlation one with the other. In theory therefore, the Watershed could have been plotted almost 450 years ago.

While there are a number of other maps from this period which would also serve to show that mapmaking had become much more sophisticated, it took another 100 years for an atlas to appear, which would be the defining publication. Joan Blaeu’sAtlasof 1665 provides a series of maps which not only show clearly the upper reaches and profiles of all of the river catchments, but also some very useful information about the general locus of the Watershed. The maps would appear to have been surveyed and hence drawn from the perspective of the lower ground; the more populated areas of the river valleys. From there, they project an image of the headwater areas as sparsely populated, with very few settlements. These areas are shown in a vague manner, with the county or geographic area boundaries sweeping through a seemingly unknown terrain; through landscapes with apparently few defining features – areas of little significance. Perhaps this says more about how these areas fitted into the warp and weft of community life than anything else. At that time there were very few roads, and wherever possible, water and sea travel was still very much the norm. The higher, remoter areas were undoubtedly less well known, and indeed of lesser importance. Their relative emptiness was real; they offered few resources that could be exploited, they were more exposed and much less fertile.

The first six-inch to the mile Ordnance Survey maps do show a watershed in a number of places, notably in the far north. These are drawn in a series of generally straight lines linking specific identifiable points, and therefore have what may be described as a rather mechanistic approach to something which in reality should be shown as an organic flowing line; for the Watershed is just that. Those areas in which a watershed is shown are far from comprehensive, and a number of lesser watersheds between river valleys are shown. So it is fair to conclude that the intention was not to delineate and show the Watershed as a whole, but rather to include a watershed when this seemed appropriate.

Part of the image of the border between Scotland and England is its troubled but colourful history. It is an area filled with the romance of stories of war and pillage, of great families constantly struggling to assert their power and control. For not only was much of this strife about the meeting of two nations frequently in dispute, but local feuds played a major part too. It is this legacy, in the form of the Border Ballads and tales that have been handed down as a celebration of great deeds, loves lost and won, truth, loyalty and despair.

Indeed, the line of the border itself took a long time to become recognised and accepted, especially at the eastern end around Berwick-upon-Tweed. But the border line as we know it today was established in 1249 with the Laws of the Marches and further ratified in 1328 at the end of the 30-year Wars of Independence – with some subsequent minor adjustments, and not a little continuing political assertion, even to the present day. The word Marchis given to meanaboundaryorfrontier; and we will hear a lot more of this. In the context of the border it is used to describe three divisions or sections, along with the hinterland on either side of this border. Each of the three Marches had its own wardens, legal and organisational arrangements; each had its own distinctive mechanisms for resolving, or attempting to resolve peaceably, disputes and offensive deeds. The three Marches were the Eastern, Middle and Western.

What is it then that determines the start or southern end of the Watershed of Scotland?

Firstly, a look at the English side to discover what forms the northern end of the watershed of England. The eastern side is straightforward, with the basin of the River Tyne which drains into the North Sea below Newcastle-upon-Tyne and which comes westwards as far as Haltwhistle on Hadrian’s Wall. But the west is less clear, as on the Western March, the border follows the Kershope Burn and the River Esk, and then jumps west to pick up the River Sark just north of Carlisle. Much of the Esk above Canonbie is in Scotland forming Eskdale, which of course rises on Eskdalemuir.

South of Kershope Forest, three rivers form the northern tributaries of the River Eden catchment which flows through Carlisle, and thence into the Solway Firth. The Rivers Lyne, King Water and Irthing respectively form the upper reaches of the western side of the watershed of England. Put simply, the River Eden and its catchment flow into the Solway Firth in the west, and the River Tyne and its catchment drains east into the North Sea. From this, the critical point is to discover where the divide appears on the border itself.

The Middle March of the border extends some 50km south west from the Cheviot to the Kershope Burn, 5km south of Newcastleton. On the English side, the Watershed comes from the south west to Peel Fell from the Larriston Fells via Deadwater. And from Peel Fell it then runs north to Hartshorn Pike, with the Scaup Burn draining to the Kielder on the one hand, and the Peel Burn draining to the Liddel Water in Liddesdale on the other. The border is therefore not quite on a watershed line between the Kielder and the Tweed catchments in this area. But further to the north east, they merge again at Carter Bar.

The summit of Peel Fell is some 50 metres or so on the English side of the border and at 602 metres is the highest point in this area. Given the drainage patterns around it, it is the logical, if not the exact, starting point for the Watershed of Scotland. The wordpeelhas a number of recognised meanings, and in this context is seen to refer to asignificant boundary– which the border most certainly is. Thus the meaning of Peel Fell can be interpreted as theboundary mountain.

Throughout the last 1,000 years of history, much of the Watershed of Scotland has been a boundary in one form or another. But it is as if it had been drawn on a map with invisible ink and needs some magic formula to be brushed on to make the line appear fully, for there are many different layers of traditional boundaries waiting to be revealed. In addition to this great east – west demarcation, it has been throughout history, and indeed continues to be, a variety of different boundaries or marches. A journey back through the pages of history begins to reveal its significance. Some 220km of the Watershed currently forms the boundary between different Local Authority areas, and thus almost one fifth of its length has a contemporary legal status, with these boundaries having been established as recently as 1996. Prior to 1975, when the old County structure disappeared, as much as 35 per cent of the Watershed was drawn as County boundary. And, since the origin of many of the counties was the earlier sherriffdoms, we see these boundaries stretch well back into medieval times.

A study of Andy Wightman’sWho Owns Scotlandshows that as much as 70 per cent of the Watershed still forms a boundary between different estates or other land holdings. There is a fence, or the remains of a fence-line, along almost three quarters of its length, and a drystane dyke on a number of short stretches. As a boundary, it will appear on countless title deeds as a March to many a farm, forest or shooting estate. The shepherds, foresters and keepers will know it well, but it is very much at the hinterland of the holdings that they patrol, and therefore the least utilised part of them. It is at the extremity – the wildest part.

Until comparatively recent times, the Parish played a major part in people’s lives – including matters of church, education, some significant aspects of administration, and social organisation in societies and other local associations. Although there were changes over the years with a slow process of Parish divisions or amalgamations, and transfer from one presbytery to another, the picture remained largely stable for hundreds of years. And this Parish structure, which was at the heart of local life, dated back to Mediaeval times. It was, however, a casualty of the Local Government re-organisation of the mid-70s, and the Parish boundaries were removed from the popular Ordnance Survey map series at about the same time. The sense of local identity which this Parish structure had maintained was replaced by the new concept ofcommunity, and the establishment of Community Councils. With as much as 80 per cent of the Watershed having formerly been Parish boundary, its significance to people living on either side of it today continues. It now marks out the upper extent of their Community Council or school catchment area, and the area of benefit for other local associations. In some places, the advent of greater mobility, which the car has brought, will have had an impact on how local is indeed local, especially in the realms of economic activity, but the concept oflocalprevails none the less.

The significance of the Parish boundary was further reinforced in historical times when witches, villains and, tragically, suicides could not be buried in consecrated ground. In such cases, a kind of no-mans-land on the Parish boundary was often chosen. How many such unmarked graves are there on the Watershed itself? No one will ever know.

So, as the magic formula is painted onto the map, and the layers of demarcation, organisation and sense of place for local people do indeed begin to emerge, it is clear that all but a small proportion of the Watershed has significance as a boundary of one sort or another. And these boundaries continue to influence people’s current thinking, identity and activity, to the present day.

When I finally set out to take a pencil and plot the Watershed on a map, the concept was relatively simple, for many of the factors I have described were fairly clear. The only real prerequisite was an ability to read and interpret a map, so the starting point was a paper exercise – no boots or walking poles required. The major river valleys and their tributaries were clearly marked, but there were a few areas which needed some more careful consideration, and these included:

Coulter to Biggar Common

Black Law wind farm to Kirk o’ Shotts transmitter

Cumbernauld

Carron Reservoir in the Campsie Fells

The Great Glen crossing

West end of Loch Quoich

Rhidorroch in Wester Ross

The northern terminus

As these sections were finally clarified thanks to some very helpful advice from Walter Stephen, a clear line was completed on my large bundle of 24 different 1:25,000 OS sheets. It was a great revelation.

The Watershed has been described as lying on the higher ground, and with an average elevation of some 450m above sea level, it is indeed often in the clouds. The lowest point is at Laggan in the Great Glen: a mere 35m, whilst the highest point is Sgurr nan Ceathreamhnan in Kintail at 1,151m. It starts at 602m on Peel Fell, finishes at 60m above the waters of the Pentland Firth, and takes in a commendable 44 Munros (mountains over 3,000ft) along the way.

It is the elevation of the Watershed that is one of its supreme qualities and makes it special. It offers wide views to the traveller, with great panoramas across vast swathes of mainland Scotland and beyond. A journey on the Watershed presents an unfolding and evolving kaleidoscope of landscape and Nature; Scotland the Best, viewed consistently from an elevated position. And it is this which gives it a unique distinction – as a single geographic feature running the length of the land, which lays the headwaters of most of the major river catchments and systems at its feet. It is a linear vantage feature from which the eye is led outwards and down the river valleys and lochs towards the coast, thus providing a tangible geographic and visual link to many of our urban settlements and wider landscapes.

The elevation of the Watershed has had another significant effect, one that generally maintains its relative wildness throughout. As our distant ancestors gradually settled and made use of the available resources around them, they chose first the coasts, islands and the lower reaches of the river plains. The process of settlement then continued further upstream, and out into the wider countryside, which saw their impact on the landscape grow and expand. Forest clearings and the emergence of basic farming, building, burial and celebration all show now as markings or shadows in the earth. And this process continued with the Roman invasion in some areas, and the seemingly empty period that followed their departure. The Church made its mark with the growth of monastic settlement and economic exploitation over wide areas, and these were in turn carved-up during the Reformation to herald the new regime. Great estates, industrialisation and an increasing urban population with its needs, all contributed to an ever-changing landscape. A myriad of other land-altering influences have all come and gone and left their mark. But throughout much of history, the higher ground had little to offer or exploit; it was the least affected by man’s efforts. Sheep and deer grazing may have had some impact on these elevated areas, but the general impression is of wilder and untamed terrain.

What then of the social and economic place of the Watershed today? In addition to its varied and only slightly diminished role as Local Government or estate boundary, the Watershed has been and continues to be a boundary in other ways. Because of the local identity which still prevails around villages and towns, the community and social organisation which this brings tends to turn its back on the higher ground; local people’s orientation is towards their own side of the Watershed, facing downstream. Without being necessarily conscious of its particular status, people’s communities of interest are demarcated in part by the Watershed. Communication plays a significant part in this, for even in this age of motor transport, there are nonetheless fewer roads and railways crossing the Watershed than there would be elsewhere further down in the river valleys. And there are no such lines of communication running along the Watershed – it is our empty quarter. If its place as a boundary of one sort or another can simply be seen as one of the majorcauses, then theeffectis its wildness.

In the past, self-sufficiency in each community for its needs, including food, materials, manufacture and commerce, would have served to limit the need to transport across the Watershed; other more accessible sources and resources would have been used when the need arose. This is not to say that people did not cross the Watershed, as there is indeed plenty of evidence where path and track crossed, but there is no doubt that it was an inhibiting factor. Whilst the decline in local production for local use has been largely replaced by national and international markets, there remains the vestige of local influence in some of the services and the more recent drive to create local markets.

That the route of the Watershed is distinctively wilder in character throughout its long meander as the backbone of Scotland is hardly surprising. As a boundary, it is at the outer limit of community, Local Authority and estate, beyond the pace of everyday life and use. Its elevation puts much of it beyond, indeed well beyond, the commercial tree line. The terrain it crosses is therefore amongst the least cultivated and wildest land, but herein lies the paradox.

The temptation to regard hill, mountain and moor, especially the more scenic areas, as entirely natural and unaffected by the actions of man, is a mistake. Whilst the tourist literature and romantic song may wax lyrical about the ‘bonnie purple heather’, or even make bolder statements about ‘last great wildernesses’, they would be misguided. There are very few places anywhere in Scotland that have either not been affected by human action in the past, or have retained a truly natural state. For much of Scotland was originally covered in trees, and what was subsequently called the Forest of Caledon, with some form of woodland cover extending well into the mountainous areas, with the more elevated areas as patchy scrub, and only the higher summits clear of it. The start of felling to make way for early forms of farming and construction dated back to the times when we made that transition from hunter-gatherers to farmers; to the point at which we became more settled. The loss or removal of trees and the erosion of forest cover is one of the significant factors in altering the nature and appearance of the landscape and its biodiversity.

Climate change some 5,000 years ago wrought further change, as cooler and wetter conditions prevailed. This period heralded the start of the formation of peat and peat-bog on a major scale in most areas; many areas of the ancient forest succumbed to this hostile habitat, and the great tree stumps which we often see today, either sticking forlornly out of the side of a peat hag or standing skeletal in the heather, are often the legacy of that climate change. The impact of this, and the evidence it has left, can be seen in many locations on the Watershed and in the surrounding landscapes.

Fast forward a few millennia then, and into the agricultural and industrial revolutions of the 18th and 19th centuries, and huge swathes of fertile land were given over to productive use. Whilst the higher more remote areas largely escaped these dramatic forms of change, they did nonetheless experience slower, but often equally profound, alteration. Over several hundred years, sheep grazing, and an increasing deer population, and a number of natural processes have gradually eroded tree cover, including those areas which are so keenly regarded as being in their natural state. Overgrazing by both species set in a cycle of decline; young tree shoots were eaten, the woodland became singularly mature, old trees fell, and there was nothing to replace them. The inevitable outcome of this process which may have taken many hundreds of years to evolve is an arboreal desert. This in turn altered the entire ecosystem, and changed everything which grew in it or sought to live on it.

There are differing theories about the overall extent of woodland loss, at what rate, and in which periods in history; and other factors have played a part too. Great loss there has been, and this has undoubtedly changed both the character and appearance of much of our landscape. It has affected the true extent of its wildness.

The definition of the term ‘wild land’ and the concept of wildness have been given greater clarity in the Scottish Natural Heritage (SNH) policy statement onWildness inScotland’s Countryside. This offers the useful distinction betweenwildness as the quality enjoyedandwild-land or places where wildness is best expressed. It expands on the importance of land use planning as the key to protecting wild land, giving Local Authorities the lead in ensuring that this is carried out effectively in their respective areas. It goes on to propose the six key attributes in the identification of wild land:

• Its perceived naturalness.

• Lack of constructions or other artefacts.

• Little evidence of contemporary land uses.

• Rugged or otherwise challenging terrain.

• Remoteness and inaccessibility.

• The extent of the area.

Having walked the whole Watershed, my direct experience is of frequent evidence of all six of these attributes, in varying degrees and combinations, and of the very largely continuous wildness as thequality enjoyed.

Clearly not all areas which might be accredited as being wild land would fully match all of these criteria, but this does offer an important yardstick in helping to pin down the principal characteristics. The report does acknowledge too that some wild land could be ‘quite close to settlements’ – the assumption that it is to be found in only the remoter uninhabited areas is misleading. This raises the issue of fences and dykes (or their remains which may be of Victorian vintage), ancient cairns, bothies, tracks, trig points, masts, pylons, and hydro-electric installations; many of these are to be found in the major wild areas. But the list of attributes of wild land provides a valuable mechanism for objectively identifying these areas.

The John Muir Trust (JMT) seeks to achieve its mission ‘to conserve and protect wild areas of the UK in their natural condition, so as to leave them unimpaired for future enjoyment and study’, through its care for wild land, wildlife, education and adventure. It has done much to establish that whilst people and wild land are inseparable, their awareness and actions are critical.

A further major milestone in promoting the care of the natural world and wild places in Scotland was reached in July 2005 when the concordat between SNH and the JMT was signed. This was informed by the earlier SNH policy onWildness in the ScottishCountrysideon the one hand, and the JMT’sWild Land Policyof 2004 on the other. It is a seminal agreement between the two key players in this field; one which will serve the interests of wild land appreciation and protection well into the future. It establishes the importance of the concept of wildness and its immense value to those who live, work and play in Scotland. A number of subsequent and indeed continuing initiatives serve to ensure that this is an evolving and progressive process.

The classification of land for agricultural purposes offers the next very useful picture in relation to the Watershed, and its suitability or otherwise, for cultivation or grazing. There are seven broad categories of potential land use:

Class Potential capability

1 Of producing a very wide range of crops

2 Of producing a wide range of crops

3 Of producing an average range of crops

4 Of producing a narrow range of crops

5 Is improved grassland

6 Is rough grazing

7 Has very limited agricultural value

Some 88 per cent of the line of the Watershed falls within either the Class 6 or 7 categories, and therefore has very limited or no agricultural value whatever. About 8 per cent would be deemed to fall within Class 5, and is thus uncultivated but capable of being used only for grazing purposes. The proportion of the Watershed which fits into Class 4 is limited to some 2.5 per cent, which could produce but a narrow range of crops, whilst only 1.5 per cent at most would be within Class 3, and support even an average range of crops. There is no Class 2 or Class 1 land anywhere on the Watershed. This exercise shows that by far the majority of the line of the Watershed is across land which is non-arable and of limited or no use agriculturally.

In gradually building the picture of the underlying factors which either serve to contribute to, or indeed define, the wilder characteristic of the Watershed, so the argument for its distinctive contribution to the geography of Scotland is expanded too. And the notion of aRibbon of Wildnessmoves on from being a rather subjective observation to a case that bears much wider scrutiny.

Although it is the hills and mountains that form the milestones along the Watershed, because theyarethe higher ground and establish the divide, it is the major rivers and their catchments that truly place the Watershed in its wider Scottish context. They describe the direction which water will take to ocean or sea; they are part of the bigger picture and provide the route for that watery journey. The author Neil Gunn, evocatively describes the life of a river:

Going from the mouth to the source, may well seem to be reversing the natural order, to be going from the death of the sea, where individuality is lost, back to the source of the stream, where individuality is born.