Robert Mangaliso Sobukwe E-Book

10,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Jonathan Ball

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

A collection of thought-provoking and moving essays on Robert Sobukwe, commissioned and edited by his biographer and friend Benjamin Pogrund. Sobukwe was a lecturer, lawyer, founding member and first president of the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC), and Robben Island prisoner.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

Robert

Mangaliso

Sobukwe

New Reflections

Edited by Benjamin Pogrund

Jonathan Ball Publishers

Johannesburg & Cape Town

Table of Contents

By the same author

By the same author

War of Words: Memoir of a South African Journalist

Nelson Mandela

Drawing Fire: Investigating the Accusations of Apartheid in Israel

Shared Histories: A Palestinian-Israeli Dialogue (co-editor)

Southern African Muckraking: 300 Years of Investigative Journalism that has Shaped the Region (part-author)

1938: Why We Must Pay Close Attention Today (part-author)

In memory of two friends and soulmates,

Bob Sobukwe and Ernie Wentzel

About this book

THE LETTER OF INVITATIONthat I sent to the contributors explains the purpose of this book:

It will be a collection of viewpoints from significant and interesting people about Robert Mangaliso Sobukwe:

(a) His life and work, and/or

(b) His current, and possible future, relevance.

Views can be supportive and/or critical. We want frank assessments and insights. The book is of course set within the South African context – past, present and future. But because of Sobukwe’s pan-Africanism, with his vision of a United States of Africa, writers can if they wish extend into the continent.

The responses were enthusiastic, and I thank all the writers who agreed to take part. They lead busy lives and many are prominent public figures. They gave time and energy to write a chapter and were helpful and courteous in dealing with my questions.

This book does not seek to present a cross-section of South African views. Instead, a mixture of logic and quirkiness went into deciding whom to invite: a particular person had expertise in regard to current events or pan-Africanism, or I thought he or she might have an unusual perspective. In the process I have renewed friendships from the past and have made new friends.

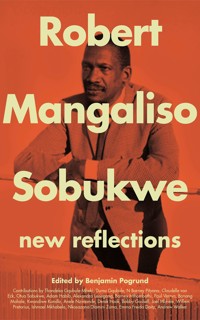

Jeremy Boraine, publishing director of Jonathan Ball Publishers, backed the idea for this book from the start, and generously left it to me to decide who would write. My thanks, too, to Alfred LeMaitre: the text has greatly benefited from his sensitive and professional editing. And thank you to the imaginative Michiel Botha, who designed the cover.

Author Peter Storey, and Gill Moodie of Tafelberg Publishers, kindly gave permission to publish an extract from I Beg to Differ.

I am grateful to my wife, Anne, for comments about the texts; to my son, Gideon, for suggesting possible contributors; and to Miliswa Sobukwe and Derek Hook for their support.

Benjamin Pogrund

October 2019

The man whose sacrifice and suffering changed South Africa

Benjamin Pogrund

Benjamin Pogrund was deputy editor of the Rand Daily Mail in Johannesburg and pioneered the reporting of black politics and existence in the mainstream South African press. He was also the southern African correspondent of the Sunday Times and TheBoston Globe. He was a close friend of Robert Sobukwe and wrote his biography. His other books include Nelson Mandela, War ofWords: Memoir of a South African Journalist, Drawing Fire: Investigating the Accusations of Apartheid in Israel,and Shared Histories: A Palestinian-Israeli Dialogue. He lives in Jerusalem.

ROBERT MANGALISO SOBUKWE’S DEFIANCEof apartheid on Monday, 21 March 1960 dramatically changed South Africa and ignited inter-national campaigning to end white rule. On that day, as leader of the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC, later the Pan Africanist Congress of Azania), he urged blacks to leave their passes at home and offer themselves for arrest at the nearest police station. The pass was the booklet used for apartheid control, recording the details where blacks could live and work; men and women had to carry it at all times or face immediate arrest. The anti-pass protest led to the police opening fire on unarmed demonstrators at Sharpeville, killing 69 people.1

Sobukwe called for ‘Service, Sacrifice, Suffering’ and said that he would not ask anyone to do what he would not do himself. He was the first to offer himself up for arrest and was sent to prison. Feared by the government, he was never allowed to be free again until his death 18 years later.

Sharpeville was so fundamental a turning point in the country’s history that today’s democratic South Africa observes 21 March every year as Human Rights Day. Reflecting its world impact, UNESCO marks this date as the International Day for the Elimination of Racial Discrimination.

Yet, despite Sobukwe’s significance in the struggle for freedom, he is unknown to the world and is ignored by many, perhaps most, South Africans. On the other hand, those who know of Sobukwe revere him as a shining exemplar of integrity for a country which, a quarter century after the end of apartheid, is beset by deep corruption and gross social and economic inequalities.

Sobukwe was born in a ramshackle black ‘location’, as the ghetto areas were known, outside the small town of Graaff-Reinet, where it was said that ‘even the dogs bark in Afrikaans’. His father, Hubert, a labourer, had been to school; his mother, Angelina, was a domestic worker and illiterate. They pushed their children to study: his father brought home discarded books from the local library (for whites only); his mother, books from white families for whom she worked. Sobukwe became not only a political leader but also an outstanding intellectual, and was nicknamed ‘Prof’. His elder brother, Ernest, was one of the first black bishops in the Anglican Church.

Sobukwe learnt his politics while studying at the blacks-only University College of Fort Hare (now the University of Fort Hare) in the late 1940s. He embraced African nationalism as the new thinking in fighting white rule. He put his views into practice as a leader in the Youth League of the African National Congress (ANC): in 1949, at the ANC’s annual conference, he helped secure a radical change in policy through the adoption of the Programme of Action. The essence of the Programme of Action was non-collaboration with the oppressor, a refusal to cooperate in implementing the growing tyranny of apartheid laws. It led the ANC to launch the Defiance Campaign in 1952, with some 10000 people of all races breaking the law and being prosecuted for using racially ‘wrong’ entrances to post offices and railway stations, or sitting on segregated park benches. But the ANC halted the campaign after the government enacted harsh new penalties and longer prison sentences, and with lashes for repeat offences.

Sobukwe and his supporters, calling themselves ‘Africanists’, accused the ANC of betraying the Programme of Action by failing to mount any more radical campaigns. They blamed communists, especially minority whites and Asians, who had been secretly influencing the ANC since the banning of the Communist Party in 1950. Amid angry internal conflict, the Africanists broke away from the ANC and in April 1959 created the PAC, with Sobukwe unanimously elected president.

He set out the main aim of the PAC: white supremacy must be destroyed. African people could be organised to do this only under the banner of African nationalism in an all-African organisation to ‘decide on the methods of struggle without interference from either so-called left-wing or right-wing groups of the minorities who arrogantly appropriate to themselves the right to plan and think for Africans’.2 Sobukwe rejected the ‘multiracialism’ of the ANC, which allowed only blacks as its members but worked with separate racial organisations for whites, coloureds and Asians in the Congress Alliance. He spoke instead of the ‘Human Race’ and sought ‘the government of the Africans, by the Africans, with everyone who owes his only loyalty to Africa and who is prepared to accept the democratic rule of an African majority being regarded as [...] African. [The PAC] guarantees no minority rights because [it] think[s] in terms of individuals, not groups.’3 And, new to the black struggle within South Africa, Sobukwe looked northward to the wave of new states obtaining their independence from European colonial powers and proclaimed the vision of a United States of Africa.

It was a powerful message, and he was hailed for revitalising and developing African nationalism. But his call for ‘Africa for Africans’ drew accusations of anti-whiteism from the mainstream press, uniformly white-owned and staffed overwhelmingly by journalists entirely ignorant of the forces at work among blacks. The negative racist image projected at this time was to persist down the years and, although entirely untrue about Sobukwe, would later be reinforced by the actions of other PAC members.

Within less than a year of the founding of the PAC, Sobukwe launched the first major campaign, aimed at the hated pass, the ‘distinctive badge of slavery and humiliation’, as he described it. But he first had to wrestle with himself: he was on the faculty of the University of the Witwatersrand (Wits University) in Johannesburg – a rare status for a black person – albeit as a ‘language assistant’ because he was denied the rank of lecturer. Although his parents were Sotho and Xhosa, he was a fluent linguist and was teaching Zulu to white students. It was at this time that the (white) Rhodes University, in what is now the Eastern Cape, offered him even greater status, as a full-time lecturer; he and his family would enjoy security and live well. He agonised and decided to turn it down, believing that his life’s mission was to commit himself to gaining freedom for his people, whatever the consequences.

He wrote to the commissioner of police about the coming launch of the anti-pass campaign. He said it would be non-violent and warned against any provocation by the police (political protests by blacks often ended with police shooting and deaths). At sunrise on the fateful Monday of 21 March, he and a small group of men – no women took part – walked to the Orlando police station in the vast black township of Soweto and demanded that they be arrested. Sobukwe was supremely confident that blacks would respond in huge numbers to his personal example: they would do so, he believed, because of their loathing of the pass system and due to the passion of his African nationalist call. He miscalculated. He also had to contend with the government’s massive intimidation of blacks. Countrywide, only small numbers of people responded – except notably in Sharpeville township, nearly 60 kilometres from Johannesburg, where up to 20000 people gathered outside the police station, and in Cape Town, where thousands protested.

The Sharpeville killings, in which scores of protesters were shot in the back as they fled, set off national and international outrage. The Afrikaner nationalist policy of apartheid – racial separateness to ensure control and privilege for the country’s white minority – had begun in 1948. Such brazen official racism, only three years after the end of Nazism and the Holocaust in Europe, had created much outrage in the world. The killings at Sharpeville and the turbulent and oppressive events that followed catapulted apartheid onto the world’s front pages. Condemnation of apartheid soared, in international forums and in popular protests and boycotts. South Africa became the polecat of the world and remained a target of attack for more than thirty years until non-racial democracy was finally achieved in 1994.

In South Africa, blacks turned to mass strikes and riots. By 25 March, the government was so rattled by the unprecedented scale of the unrest that it announced the suspension of pass arrests, giving the PAC an exceptional victory. The ANC had rejected Sobukwe’s appeal to join the anti-pass action but, responding to the public rage, on 28 March its leaders publicly burned their passes and declared a national day of mourning. Sobukwe, locked up in prison, criticised them as unprincipled opportunists. In Cape Town on 30 March, a PAC leader emerged – a young university student named Philip Kgosana – who led 30000 blacks in a march to the city centre, stopping them four blocks from the whites-only Parliament. The marchers scrupulously obeyed Sobukwe’s instruction to be peaceful. But the government was terrified that they might tear the city centre apart and promised Kgosana a meeting with a cabinet minister if he marched the crowd back to the townships. He did so. But he was a victim of cynical crookery: when he returned for the meeting later in the day, he was seized by the police, detained and kept without trial for four months.Armed police and soldiers surrounded and moved into the townships in strength and, going from door to door, brutally suppressed protest.

The government could do what it wanted because on that day it declared a state of emergency. In mass raids by the security police, about 1800 people of all races with any history of opposing apartheid were detained without trial, as well as another 18000 blacks deemed to be ‘vagrants’. On 8 April, the PAC and the ANC were declared illegal. On 9 April, in the fevered climate of the time, a white farmer shot the prime minister, Dr HF Verwoerd; he survived, and the farmer was said to be insane. On 10 April, pass arrests resumed. The government was again in control. But the country, shaken to its roots, was changed forever.

The defects of the PAC’s campaign against the pass system now became evident.The entire National Executive, except for two members, had willingly gone to prison with the slogan, ‘No bail, no defence, no fine’. It was brave, noble and inspirational. It was also politically naive because the organisation was so new that there was no second level of leadership to take over. For the next two years, the effective president was a shy and inarticulate man who had been doing some typing in the PAC’s office.

In Johannesburg, Sobukwe and his colleagues were charged with and found guilty of ‘incitement’. He was sentenced to three years’ imprisonment with hard labour. Breaking the campaign promise, the PAC men lodged an appeal, but lost. There was no early parole. As the date of Sobukwe’s release – 3 May 1963 – approached, the government rushed a special law through Parliament specifying that a security prisoner could continue to be kept in jail without trial for a year at a time, renewable indefinitely. Dubbed the ‘Sobukwe Clause’, it was only ever applied to Sobukwe himself. He was taken to Robben Island, off the Cape Town coast, the new maximum-security prison for the rising number of political prisoners after Sharpeville. All the warders were white.

Sobukwe was kept on his own in two sparsely furnished rooms inside a barbed-wire stockade, guarded day and night. He could wear his own clothes, his food was provided from the warders’ kitchen, he could work on his university studies and he could write and receive a restricted number of letters (but was never told whenever warders seized these). He could have occasional visitors, and later his wife, Veronica Zodwa, and their four children were allowed to spend a week locked up with him, but he had to pay for their meals. There was no contact with the rest of the prisoners on the island, except sometimes a distant view when they were taken to work.

— —— —

Bishop Peter Storey was a young Methodist priest when he was assigned to minister to the prisoners on Robben Island. In his book I Beg to Differ (Tafelberg, 2018), he gives a moving account of his encounters with Sobukwe:

Sobukwe had been a Methodist lay preacher, so I asked to see him. I was refused at first, but some persistence revealed that the authorities were legally obliged to give me access. For every visit, however, I had first to get written authority from the Chief Magistrate of Cape Town.

By the time I visited him, Robert Sobukwe had already earned the grudging respect of his gaolers. My driver, a tough non-commissioned officer in his fifties, remarked that none of the baiting by bored young guards around the perimeter had succeeded in evoking a reaction from him. ‘Every morning, this man comes out of his house dressed as if he is going off to work,’ he said. ‘He is very dignified.’

As we approached the weathered hut, I wondered what kind of welcome I would receive. The SABC and the press had portrayed Sobukwe as a dangerous black nationalist with a hatred of whites. Would he want to see me – a young white minister?

Sobukwe met me on the steps of his bungalow. I was immediately struck by his handsomely chiselled features and patrician bearing. Tall and wiry and dressed in neat slacks and a white shirt and tie, he offered me a guarded but polite welcome, inviting me inside as if this was his own home and I was a guest coming for tea. The room we entered served as both bedroom and living space, with a neatly made bed, a simple bedside cabinet, a table and chair, and a small bookcase. It was spartan but adequate. Sobukwe gestured to the only chair and sat on the edge of the bed. Conversation was desultory at first. I knew he was sizing me up and didn’t blame him. I said that many Methodists would be excited to know that one of our ministers had got to see him.We swopped names of mutual acquaintances and stories of Healdtown, the Methodist college both he and Nelson Mandela had attended. It was the year that Reverend Seth Mokitimi was about to be elected the first black President of MCS (Methodist Church of South Africa) and he spoke admiringly of Mokitimi’s influence as a chaplain and housemaster at Healdtown.

Our conversation soon warmed, and after that, each time I came to the island we were able to have about thirty minutes together. He had a consistent aura of calm about him, sucking contentedly on his pipe while we talked. He chose his words carefully, spoke quietly, and had a gentle sense of humour. Our discussions were perforce circumscribed, always in the presence of the guard, who stood near the door, pretending to be uninterested. Even so, it was possible to engage something of the depth and breadth of his thinking. His Christian faith was informed by wide reading and it was quite clear that he saw his political activism as an extension of his spirituality. He was excited by Alan Walker’s 1963 preaching campaign in our country, and the furore around Walker’s challenge to the apartheid state. This was the kind of witness he expected of his own church leaders, only to be frequently disappointed. He was impressed when I told him I was hoping to go and work under Walker for a year. I was later permitted to bring him a few theological books, and included all of Walker’s writings. Both of us being pipe-smokers, I could also bring his favourite tobacco and we used to chuckle that both this Methodist minister and lay preacher had a taste for Three Nuns blend.

Robert Sobukwe impacted me very powerfully. For all my contact with black South Africans, here, for the first time, I was engaging with somebody risking all for the liberation of his people. The calibre of this man, the cruel waste of his gifts, and the silence of most South African Christians around his incarceration, touched me to anger. On his part, he always expressed genuine appreciation of our times together, but even though I was the only person, apart from his captors, ever permitted to see him, I sensed that he would never put too much trust in these visits. Why should he place faith in this white man, any more than any other? I always came away angered and ashamed. Once, when leaving him, I expressed my shame that I could depart the island so freely, leaving him a prisoner. His response was quick. Gesturing toward Cape Town, with its Houses of Parliament occupied by his tormentors, he said, ‘I’m not the prisoner, Peter – they are.’

Every visit made it more evident to me why the apartheid government feared Robert Sobukwe so much.

—

Sobukwe’s isolation and never knowing when he might be released went on for six years. He was allowed occasional visitors, and he told one of them that he was forgetting how to speak. The strain finally began to tell and he was hurriedly removed from the island and banished to Kimberley, 480 kilometres west of Johannesburg. He was dumped among strangers in a large house with little furniture in Galeshewe township. Veronica Zodwa (who later also used the name Zondeni) joined him. He was subjected to severe restrictions: house arrest from sunset to sunrise and over weekends. He could not be with more than one person at a time. Nothing he said or wrote could be quoted. He was not allowed to leave the township and could not enter schools or factories without permission. Despite the obstacles, he qualified as an attorney and opened a practice. He was called the ‘social-welfare lawyer’ because he charged clients little or nothing.

After nine years, he was diagnosed with lung cancer. The restrictions on his freedom of movement delayed getting treatment that might have saved his life. A doctor who met him then spoke of his ‘grace and dignity’. A former Methodist minister quoted the dying Sobukwe as praying: ‘Father, forgive them … Take away all bitterness from us and help us to work for a country where we will all love each other, and not hate each other because hate will destroy us all.’ He died in February 1978 and was buried in Graaff-Reinet.

The reason for the extreme restrictions was simple: the government feared Sobukwe. It feared his personal strength and courage, his commitment to fighting for freedom, his eloquence, his quiet charisma and his enunciation of African nationalism. He was closely watched during his initial three years in jail, and the security authorities concluded that this was an enemy too dangerous to be let loose. The same happened on Robben Island, this time to the extent that within the first year the government in effect threw away the key and decided to let him rot in virtual solitary confinement. Only the deterioration in his health led to his banishment to Kimberley, where he was always under surveillance and his visitors followed.4 The police were not always successful: the next crop of political leaders in the Black Consciousness Movement (BCM) regularly slipped in to seek his views.

Keeping Sobukwe out of public sight for so many years, and the pitiless treatment that was meted out to him, inevitably gave rise to rumours. Three in particular have spread, although none have any basis in fact. The first is that on Robben Island his food was laced with broken glass with the intention of harming or killing him. This did indeed happen on one occasion, but there is no reason to believe that it was an official action; indeed, the prison authorities were highly alarmed by it. Second is the allegation that his death was caused by poisoning. But the facts are that he had tuberculosis as a young man, he was a smoker for much of his life and he was a victim of lung cancer.

The conspiracy stories persist, and with time grow even more lurid. Thus, ‘he was fed glass’.5 And, even more absurdly, the ‘authorities allegedly continually mixed his food with the glass of a finely crushed bottle to covertly kill him through a slow and painful death, medically diagnosed as cancer’.6 In a wholesale collection of fabrications, he was said to have been ‘poisoned on Robben Island’; he was ‘systematically assassinated … by the collaboration of the racist apartheid state with the medical establishment’; at Cape Town’s Groote Schuur Hospital he was operated on for ‘an alleged cancer tumour’ by Dr Chris Barnard (the heart-transplant surgeon) ‘without the knowledge of his family’; he ‘did not die a natural death’.7 (For the record: it was cancer, Dr Barnard was not the surgeon, and the family was fully informed.)

The third spurious claim has to do with the fact that no TV footage of Sobukwe exists, nor has any recording of his voice been found. This has spawned allegations that his voice has been deliberately obliterated by unnamed enemies in order to wipe him out of history. However, the explanation is straightforward: when he was a free man, TV and audio recordings were unusual in South Africa; then he was locked in prison out of sight and sound for nine years; and when he was banished to Kimberley, he was under banning orders that made it illegal for anything he said to be recorded or reported. The security police were watching him: they could have intercepted anyone making a recording – and Sobukwe would have faced serious criminal charges for breaking his banning order. So, no recordings of his voice were made. It would have been too dangerous.

Does it matter that these falsehoods and distortions are being peddled? Robert Sobukwe lived a life of personal honesty and integrity. His legacy demands that his life story be told untainted by untruths circulated by people who either don’t know or are playing to some political agenda of their own. He suffered so terribly under apartheid that there is no need to invent or exaggerate what happened to him. Sticking to the truth is enough and is what he deserves.

—

Post-Sharpeville, with the PAC and ANC proscribed and driven underground, many blacks despaired of whites ever peaceably yielding power. Unknown to Sobukwe, a movement dedicated to the mass murder of whites emerged inside the PAC: called Poqo (Our Own), it carried out several attacks until the police learnt of its existence, only days before countywide violence was due to start. More than 3 200 men were arrested; their trials went on for months, and led to the imposition of the death penalty or lengthy prison sentences on Robben Island.

The PAC’s general secretary, Potlako Leballo, after two years in prison, left the country to lead Poqo, and then the PAC, in exile. As a speaker, Leballo could bring a crowd to its feet within minutes with a screaming, incoherent rant against whites. The PAC enjoyed support in newly independent countries because of its Africanism, but Leballo squandered this goodwill. The PAC fell into internal murders and theft of funds. Out of Poqo came the Azanian People’s Liberation Army (Apla), which, right until to the coming of democracy in 1994, was killing white civilians under its slogan of‘One settler, one bullet’. In the general elections that year, the PAC won 1.2 per cent of the votes; later this slumped to 0.7 per cent. Today’s PAC can hardly be compared with the organisation led by Sobukwe. Still riven by dissent, its president, Narius Moloto, claims that the PAC has 100 000 members.8

The ANC, on the other hand, maintained its dominance. Together with the Communist Party, it formed Umkhonto we Sizwe (Spear of the Nation) in 1961 to mount armed resistance against apartheid. It decided to attack property, not people, and this policy was largely adhered to in the years that followed. The ANC opened its membership to people of all races in 1969. It won overwhelmingly in the democratic elections of 1994, under the leadership of Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela, who earned national and international admiration for his humanity and lack of bitterness towards the whites who had kept him imprisoned for 27 years. He and Sobukwe had been colleagues in the ANC, but the PAC’s breakaway made them political rivals. They were brought together at one time in Pretoria Prison, sitting side by side on the concrete floor repairing canvas mailbags and discussing who was the world’s best English-language author.

The ANC has retained political power, though its popular support has been slipping. It honours the leaders of its struggle against apartheid, with Mandela deservedly the icon, but brushes rivals aside, Sobukwe more than anyone else. His name is even usually excluded, along with that of the PAC, from references to the turning-point Sharpeville massacre. It is as though he had nothing to do with it. Denied national recognition, Sobukwe has been written out of history.

However, Mandela himself, while president, did not forget Sobukwe. A simple ceremony in December 1997 to present Sobukwe documents to Wits University’s Africana Library was transformed into a special event because Mandela heard of it and came ‘to pay homage’ to Sobukwe.9

—

South Africans have freedom. And millions are better off in their daily lives. Yet the dreams and hopes of millions have not been realised: they lack clean water, they cannot get work, they live in iron and cardboard shanties, their children get low-quality schooling and healthcare is poor. HIV/Aids is widespread. They suffer robbery, murder and rape. Their plight, caused by government failure and incompetence, grew more acute during the nine years that Jacob Zuma was president: the cost of so-called state capture – corruption by private individuals and corporations in league with the highest levels of officials – cost the country many billions of rands. Zuma was deposed in February 2018 and replaced by Cyril Ramaphosa, who has a long way to go to repair the damage.

Starting only a few years ago, Sobukwe’s name began to circulate as an example of what a leader should be: one with honesty, integrity and commitment, who would not have tolerated the harsh social inequalities of today. And with pressure mounting for redistribution of land, to make reparation for the land historically stolen by whites from blacks, there is renewed interest in Sobukwe’s African nationalism (although his qualification that ‘Africa for Africans’ is colour-blind is not always appreciated).

As a sign of changing attitudes, in September 2017, Wits University named the central building at the heart of its campus the Robert Sobukwe Block – with a bit of rewriting of history by saying Sobukwe had been a ‘lecturer’. Criticism of the lack of recognition of Sobukwe has become a repeated, often angry theme. Early in 2018, a newspaper headline read: ‘Conspiracy of silence circles Sobukwe’.10 Another headline was, ‘The nation needs a Sobukwe Day’, noting that he ‘deserves to be honoured more substantially by the national government in recognition of his leadership and sacrifice’.11 In a letter to The Star, a reader complained: ‘Sobukwe’s ideas and teachings remain suppressed, and I am also a victim of that unjust act. For 12 full years of my life in a government schoolI have never heard of his name, or even his organisation …’12

Great plans to lionise the memory of Sobukwe as an ‘intellectual and leader’ referred to plans by the Vaal University of Technology to establish an African cultural museum.13 A review of TheBlack Consciousness Reader14 said: ‘Forgotten heroes deliver a timely lesson on struggle: New book places young lions like Mangaliso Sobukwe at the front of the fight against apartheid and colonialism’.15 Getting to the nub of it was an article by Panashe Chigumadzi titled ‘ANC version of history overshadows the real story of resistance’,16 while a letter to the Sunday Times was topped by the headline: ‘History belongs to the victors’.17

In 2019, Wits University Press published Sobukwe’s Robben Island correspondence. Titled Lie on Your Wounds: The Prison Correspondence of Robert Mangaliso Sobukwe, the book was edited by Dr Derek Hook of Duquesne University, Pittsburgh. The psychologist and educationist Professor N Chabani Mangani said the letters ‘represent the height of human decency in the face of unmitigated racist apartheid white tyranny’.

—

Veronica Zodwa Zondeni lived for 40 years after her husband’s death. She had been steadfast and she went on enduring, with immense dignity. Shy and reticent, Veronica avoided publicity but fought unremittingly for her husband and family. The government ignored her until very late in her life when she – aged 90 – was given a national honour in April 2018; she was too ill to attend the ceremony in Pretoria. One writer said of the belated recognition that it was ‘a shameful indictment on the conscience of a government that is structurally biased and selective in whose contributions and legacies it celebrates and whose memories it remembers’.18 Veronica passed away on 15 August 2018. President Cyril Ramaphosa ordered flags to be flown at half-mast and for her to have a ‘Category 2’ state funeral. Unfortunately, the ANC showed arrogance and insensitivity in running the funeral, starting with the cabinet minister in charge giving the ‘Amandla!’ (‘Power!’) salute – the hallmark of the ANC – rather than the Africanist ‘Izwe Lethu’ (‘It is Ours’) salute. . A group in the divided PAC took over and ordered the government leaders to leave. The funeral was chaotic and did not do Veronica justice.

Among the countrywide outpouring of tributes to her was this Facebook post on 18 August 2018 by Modise Moiloanyane:

Mama Sobukwe! May your soul rest in peace! Please convey our warm greetings to Prof! You have run your race, you were a revolutionary and played a gallant role amongst our Women warriors. Many don’t know your struggles, many don’t even know you. Many suppressed who you are and your contribution to our beautiful land. Many and most of them in power are and were afraid to tell us about you and Prof Mangaliso Sobukwe because they know that your contributions to our free land will dwarf their claim to victory. We love you and may you rest in peace amongst our gallant martyrs!

—

That Sobukwe’s memory and example are at last coming to the fore was projected in a large headline in The Star in July 2018: ‘The indomitable spirit of Sobukwe is testament to our African agenda.’19 It wasn’t only the words and the thought but also the writer who made this so striking, even startling: she was Dr Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma, who is in the top ranks of the ANC leadership, came close to winning the presidential contest against Ramaphosa in 2017, serves as a minister in the Presidency, and is a former chairperson of the African Union.

At a personal level, there is Johnson Mlambo. At the age of 23, Mlambo was sentenced to 20 years’ imprisonment for his involvement with Poqo. He served his sentence in full. He was tortured by sadistic warders on Robben Island. Once, warders buried him up to his neck in the ground and urinated on his face. He still suffers back pain from the blows and kicks. After his release, he escaped from the country and led the PAC in exile. He now lives quietly outside Johannesburg with his wife, Nomsa, who he met after his prison term. He never met Sobukwe but saw him at a distance on the island. Mlambo explains Sobukwe’s profound effect on his life:20

To inspire us to leave our passes at home and surrender ourselves was a very big task. The police couldn’t believe that these people who were always running away were able to come and say they wouldn’t carry passes any more. Sobukwe lived up to his commitments. I was saying to myself as a young man, if this man who is the best of all of us, could sacrifice his very high position at the university, could sacrifice his own peace and welfare, why can’t I emulate him?

A voice that could not be silenced

N Barney Pityana

Nyameko Barney Pityana was a founding member of the Black Consciousness Movement (BCM). Banned by the government, he went to study theology at King’s College London, and was ordained as an Anglican Church minister. He was Vice Chancellor of the University of South Africa (Unisa) and is Professor Emeritus of Law. He is Visiting Professor at the Allan Gray Centre for Leadership Ethics (AGCLE) at Rhodes University, and a Fellow at the Stellenbosch Institute for Advanced Study (STIAS), Stellenbosch University.He holds the Order of the Grand Counsellor of the Baobab (Silver).

ROBERT MANGALISO SOBUKWE, POPULARLYknown as ‘Prof’, was at the prime of his life when he passed away on 27 February 1978, at the age of 53. However, he had packed so much into a young and brief candle of a life that his example is of enduring significance and meaning for South Africa. After all, he was 35 when he led a demonstration by the Pan Africanist Congress of Azania (PAC) against the pass laws, confronting a system of injustice with the moral power of defiance. For that he paid dearly. He was jailed for three years, after which, by a device that came to be known as the Sobukwe Clause of the General Law Amendment Act, he was kept in solitary confinement on Robben Island and then banned and banished to Kimberley. He died without ever having tasted freedom since 1960.

The PAC held its founding congress on 6 April 1959, with Sobukwe as its inaugural president.The PAC was a faction of pan-Africanists who had left the African National Congress (ANC) out of disillusionment with the adoption of the Freedom Charter in 1955.At the time, the PAC promised to bring vigour and a radical posture to resistance against apartheid. More importantly, the PAC redefined its ideological position as both pan-Africanist and unapologetically radical in the urgency and methods of struggle. For that, the PAC attracted a great deal of attention in its early life and drew into its ranks many younger African activists who were eager for a phase of struggle defined by an uncompromising impatience for freedom.

One must remember that the PAC operated for barely one year before the 1960 campaign against the pass laws that resulted in the Sharpeville massacre, and the demonstration that led to Sobukwe and many leaders of the PAC being arrested and incarcerated for long periods. This meant that this young political organisation might not have been firmly established enough before the events that shook it to the core in 1960 crippled its capacity to function effectively.Yet, remarkably, the PAC did make its mark in the politics of liberation of South Africa and competed as equals with the ANC, the much older and more traditional political organisation of the mass of the oppressed people of South Africa. Even more so, as the ANC and the PAC were banned organisations under the most repressive security laws of the apartheid regime, the PAC was never able to develop a strong culture of leadership and to become as deeply established in the minds of the masses as was the case with the ANC.

The span of lawful operation of the PAC was exceedingly short – less than one year! But the PAC never died. Strategies and tactics changed even though many of its leaders were in jail, but more importantly, the PAC adopted armed struggle and established the Azanian People’s Liberation Army (Apla). The assessment of the effectiveness of the PAC as a liberation organisation alongside the ANC is not the subject of this chapter. What it seeks to do is to assess the legacy of Robert Mangaliso Sobukwe, his ideas and their influence on subsequent developments in South Africa’s political and constitutional landscape.

—

The funeral of Zondeni Veronica Sobukwe, Robert Sobukwe’s widow, who died aged 90, was held at his birthplace, Graaff-Reinet, on 25 August 2018. President Cyril Ramaphosa declared it a special official funeral in honour of Mrs Sobukwe, and no doubt of her pre-deceased husband. As it turned out, the funeral became a spectacle on the sad state of affairs in Sobukwe’s beloved PAC. Factions of the PAC denounced the party’s leadership and appeared to pledge allegiance to a former president who had been expelled from the party but who remained its sole representative in Parliament in defiance of the party.

More dramatically, the confusion not only pained the Sobukwe family, who were in mourning, but also undermined the family’s efforts at conciliation by seeking to negotiate with all the factions of the PAC to ensure a funeral that would be worthy of the honour justly deserved by Mrs Sobukwe.

Finally, the histrionics of the day were directed against the very idea of a ‘state funeral’. Significantly, the protesting faction rejected the role undertaken by cabinet ministers deployed for the occasion, including the deputy president, who was to deliver a eulogy on behalf of the government. There was contestation about the role of the South African National Defence Force (SANDF), and the Chaplain-General, and most explosively, against the use of the South African flag that had draped the coffin of the departed.

I attended the funeral as a speaker from the National Foundations Dialogue Initiative (NFDI), a collection of foundations established to champion the legacies of former leaders in the liberation struggle, and which continue to seek to advance a vision of South Africa established under the constitutional democracy model of the new dispensation since 1994. As the Robert Sobukwe Trust is an affiliate member of the NFDI, it was correct for the NFDI to attend and to honour such a stalwart of our struggle as Mrs Sobukwe. In the event, I found myself occupying a front row in the dispute that unfolded.

There were moments when I became confused about what exactly the dispute was about. Was it about the struggle for ascendancy and relevance within the PAC, or was it a more fundamental dispute about the nature of the South African state? It may well be the case that the two questions are interrelated and suggest that, in the minds of at least some within the PAC, the struggle was not resolved in 1994, and that the factional struggles within the PAC have, in part at least, to do with the ideological questions about South Africa and its future.

I remembered that the PAC had chosen to remain outside the Convention for a Democratic South Africa (Codesa) process from 1990 that led to the constitutional democracy on which we now pride ourselves. The party did not seem to have a common negotiating position about how to resolve the question of apartheid. It must be recorded that even up to 1993, acts of violence attributable to Apla were staged in places such as Cape Town and elsewhere. When the PAC eventually decided to agree to contest the 1994 general elections, it had neither the resources nor the organisational power, nor a coherent message to offer to the electorate. No wonder, then, that it received less than one per cent of the popular vote.