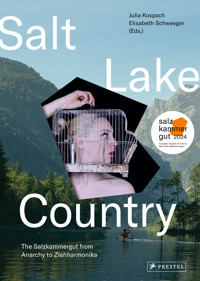

Salt Lake Country E-Book

26,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Prestel

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

A story about the Salzkammergut region as the heart of Austria - European Capital of Culture 2024.

Naturally compact, with its characteristic mountains, lakes and rivers that divide as well as connect, the Salzkammergut typifies many other parts of the world, showing how we can meet the increasing political, cultural, commercial and environmental challenges facing Europe and the globe.

60 short essays, cartoons and literary and artistic opinion pieces offer a range of perspectives on the region and its nature, culture, history and people. Written by renowned figures from literature, the sciences and art, the essays are informative, educational, effusive, critical and witty, and give deep insights into the Salzkammergut.

Contributors include Bettina Balàka, Markus Binder, Isolde Charim, Conchita Wurst, Mareike Fallwickl, René Freund, Barbara Frischmuth, Hubert von Goisern, Andrea Grill, Rudolf Habringer, Gerhard Haderer, Angelika Hager, Bodo Hell, Johannes Jetschgo, Franz Kain, Günter Kaindlstorfer, Edith Kneifl, Julia Kospach, Sarah Kuratle, Nicolas Mahler, Stephen M. Mautner, Eva Menasse, Nick Oberthaler, Walter Pilar, Helga Rabl-Stadler, Hans Reschreiter, Andrea Roedig, Franz Schuh, Elfie Semotan, Magdalena Stammler, Liv Strömquist, Anton Thuswaldner, Bernadette Wegenstein and more.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

ANARCHISCHER GEIST

THE SPIRIT OF ANARCHY

ATTERSEE

ATTERSEE

DER BERG SPRICHT

THE MOUNTAIN THAT SPEAKS

BERNHARD, THOMAS

BERNHARD, THOMAS

BRAUCHTUM

CUSTOMS

CUM GRANO SALIS

CUM GRANO SALIS

DACHSTEIN

DACHSTEIN

DIRNDL

DIRNDL

DREIUNDZWANZIG FÜR VIERUNDZWANZIG

TWENTY-THREE FOR TWENTY-FOUR

DIE EHRENWERTEN

HONOURABLE MEN

ENGE

SHUT IN

DER ENTHUSIAST

THE ENTHUSIAST

ES WAR EINMAL...

ONCE UPON A TIME...

EX LIBRIS

EX LIBRIS

FEMINISTISCHE GSTANZLN

FEMINIST 4-LINERS

FEST IM SATTEL

THE PLACE NO MAN CAN GET TO

FILMWELTEN

FILM WORLDS

FRAUENALLTAG IM SALZGEBIRG

WOMEN IN THE SALZGEBIRG

GEHEIMSACHE

STRICTLY CONFIDENTIAL

GENIALES VERSTECK

INGENIOUS HIDEOUT

GLAMOUR

GLAMOUR

HABSBURG FOREVER

HABSBURG FOREVER

HANDWERK

THE CRAFTS

HIMMEL UND HÖLLE

HEAVEN AND HELL

JA, BITTE

YES, PLEASE

JODELN

YODELLING

DES KAISERS GELD

THE EMPEROR’S RICHES

KERAMIK

CERAMICS

KITSCH & KLISCHEE

KITSCH & CLICHÉS

KOEXISTENZEN

COEXISTENCES

KREISLAUFWIRTSCHAFT

CIRCULAR ECONOMY

LEDERHOSEN

LEDERHOSEN

LEERSTAND & VERSIEGELUNG

VACANCY & SOIL SEALING

MA, IST DAS SCHÖN!

SOOO BEAUTIFUL!

NARZISSE

NARCISSI

NEIN, DANKE

NO, THANK YOU

NEXT GENERATION YOU

NEXT GENERATION YOU

OVERTOURISM

OVER-TOURISM

PARALLELWELTEN

PARALLEL WORLDS

QUEER

QUEER

DIE RÜCKKEHR

THE RETURN

SALZBURG-CONNECTION

THE SALZBURG CONNECTION

SCHNEE

SNOW

SCHNÜRLREGEN, ADÉ

THE END OF RAIN

SEE

LAKE

SEHNSUCHT

LONGING

SISI 1 ROMYFIZIERUNG

SISI 1 ROMYFICATION

SISI 2 IM SPIEGELSAAL

SISI 2 IN THE HALL OF MIRRORS

TRADITION

TRADITION

TRAUNSEHER

TRAUNSEHER

ÜBERLEBEN

SURVIVAL

VEREINSKULTUR

CLUBS AND SOCIETIES

VERGESSENER SALON

THE FORGOTTEN SALON

EINE VOGELGESCHICHTE

BIRD STORY

VON EINEM, DER AUSZOG, UM WIEDERZUKEHREN

ON LEAVING HOME – AND THEN RETURNING

WALD

WOODS

WARTEN AUF FRAU WOLF

WAITING FOR FRAU WOLF

WIDERSTAND

RESISTANCE

ZAUNER

ZAUNER

ZIEHHARMONIKA

DIATONIC ACCORDION

Appendix

Glossary

Register

Vitae

INTRODUCTION

The Salzkammergut – so beautiful, so full of contradictions, so headstrong. And now it’s a European Capital of Culture. For the first time in the history of the Capitals of Culture, an Alpine region has won the title; an Alpine region in Austria where 23 communities have come together to form the European Capital of Culture Bad Ischl Salzkammergut 2024 and mark the occasion by addressing their history, taking stock of their present and envisioning their future.

Historically, the nature, economic environment, society, culture and people of the Salzkammergut have very much been shaped by the “white gold” that is salt. The salt trade has nourished and enriched the region and connected it with the rest of the world. It has also attracted wealthy and powerful people, who have left their mark, with the Viennese court and its entourage making the Salzkammergut a byword for summer retreats: with the arrival of city-dwellers and their culture, it became a sought-after place where people longed to be.

Naturally compact, with its characteristic mountains, lakes and rivers that divide as well as connect, the Salzkammergut typifies many other parts of the world. It reflects the global divide we see between the industrialised north and the agrarian and tourism-based south, albeit in condensed form. The region represents both a shining example and a testbed for exploring how we can rise to the political, cultural, commercial and environmental challenges facing Europe and the world.

To portray such a historic region and its nature, cultural history and people in their full complexity is almost impossible to do exhaustively. For this reason, this book of prose, poetry and pictures sets out to deliver a renewed survey of the Salzkammergut: in essays and images, poems and drawings, cartoons and paintings, short stories and life stories, conversations and pictures, finds and discoveries, and from prospective and retrospective viewpoints. Informative, educational, effusive, critical and witty, the writings combine to form an extensive, kaleidoscopic view of the Salzkammergut and of the soul of this vibrant rural region. They shine a light not just on its radiant beauty but also on its darker corners. Each chapter explores its own area of detail – but together the texts read like a pointillist painting and ideally broaden the reader’s view of the Salzkammergut. Liberated from the often overwhelming postcard idylls and stubborn clichés, they offer a surprisingly fresh and novel perspective, revealing how numerous small elements – the 23 very diverse communities – together create a bigger picture: the Salzkammergut, its three constituent federal states Upper Austria, Styria and Salzburg, Austria and beyond.

The themes in this book are organised alphabetically by their German titles, like dictionary entries from A to Z. From anarchy and confinement, dirndl-dresses and lederhosen, and lakes and snow to the Habsburgs and overtourism, queerness at carnival and Ziehharmonika accordions, each subject area relates directly to the Salzkammergut, reflecting the everyday, shining a light on the past, and bringing background to the fore. Feeling the pulse of the Salzkammergut, the reader is invited to zero in on details but also to zoom out again for a birds-eye view. The chapters of this book are written by people with close ties to the region, who have been shaped by it or grew up here – but also by people taking an outside view and comparing the Salzkammergut with other places. And then there are those who only came into contact with the Salzkammergut through its Capital of Culture status, or whose artistic works deal with materials and themes that are important for the region.

The images we have combined with the texts only rarely illustrate directly what the text is about. Far more, they are art- and craftworks in their own right, sometimes complementing what has been written, sometimes adding a note of irony, a contrast or an extra dimension, and on occasions being only loosely associated with it. The images tell their own visual story of the Salzkammergut and of the diverse worlds of national and international artists converging here in the year of the Capital of Culture.

Effusive or melancholic, provoking smiles, astonishment, shame, enthusiasm, laughter or tears – this book is a critical declaration of love to the Salzkammergut, its people and its visitors. ■

Julia Kospach Elisabeth Schweeger

Anarchischer Geist

The Spirit of Anarchy

René Freund

Observations on the flourishing stubbornness,resistance and traditions in the Salzkammergut

On 30 April, villages across the Salzkammergut put up their maypoles. According to ancient tradition, the maypoles must be closely guarded until the morning of 1 May, not just so they don’t get damaged by Walpurgis Night witches but also so they don’t get pinched by some dauntless lads from a nearby village. Which would, of course, mean total humiliation for the victims of the theft.

Maypole stealing isn’t actually covered by the law, so it’s quite anarchic in and of itself. But in one instance anarchy turned to recklessness when a closeknit gang from a small village in the Salzkammergut hit on the idea of stealing the maypole in Linz. The young men got into a semi-trailer and drove off to the town’s main square without thinking anything of it. There, they chopped down the unsupervised maypole, loaded it up and took it away. Legend has it that the next day the Mayor of Linz flew into an absolute rage, but he still had to pay a ransom of a few crates of beer to get his maypole back.

A placard in support of the deeply rooted local tradition of birdcatching, Bad Goisern, 2005

HANGING SANTAS

Still in the spirit of anarchy but in a different season, here’s a story that came to pass one Advent. One morning, much to their surprise, the people of a village near Lake Traunsee woke up to find Santa Clauses dangling from their lamp posts. They were the kind of lit-up, scaling-a-wall Santas you can buy at the DIY shop and that people-with-absolutely-no-taste like to stick on their houses for Advent. In protest at their ugliness – and perhaps at the imperialism of the US Santa – local arbiters of style had kidnapped and subjected them to mass public execution. Ho, ho, ho! Not a pretty sight. But then nor are Santas climbing up houses.

There is, of course, a difference between political and personal anarchy. The spirit of anarchy in the Salzkammergut is very clearly the latter: people like to attract attention to their personal protests and often do so in highly novel ways. But you do need to keep your wits about you, as in this part of the world the line between anarchic intervention and mob justice is pretty blurred.

And protests are not always non-violent either. I once heard about a farmer who wanted to sell a piece of land to a supermarket chain. When word got out, a group of locals got together, pulled a sack over his head and roughed him up until he gave in. Another time there was a forester who had warned people to keep to the rules. He woke up one morning to find his garden fence had been adorned – with the severed heads of stags impaled on the pickets.

SHOCKING FRANKNESS

In my first few years in the Salzkammergut I found the prevailing ‘directness’ – to use a euphemism – of communications here slightly disconcerting. But with time I have come to understand the great benefit of it, which is that I get to be straight with people as well. Not beating about the bush like the Viennese do took some getting used to. As did the frankness of people like the organiser of one of my local readings, who said to me afterwards that this time my performance had been “really crap”.

In this part of the world people don’t take offence that easily. In fact, it’s good form to be a little quarrelsome.

HIGHPOINTS OF INSTITUTIONALISED ANARCHY

Here in the Salzkammergut a certain lawlessness is normal and practised with pleasurable defiance. I often get the impression everyone just does what they want – which is also a form of anarchy: if you feel like mowing the lawn on a Sunday, then you do. There’s always a power saw clattering and growling somewhere as well, no matter what time of day or night, be it on public holidays or weekends. As for the moped rider who saves me the bother of setting an alarm by howling past my house at half past six in the mornings on his selftuned set of wheels: in Vienna he wouldn’t have lasted ten minutes before being taken off the road. And then there’s the community-spirited neighbour who, at a town hall meeting with the Mayor, requested a 30 kilometre an hour speed limit for the centre of Grünau. She nearly suffered the same fate as the Santas I mentioned at the beginning. Thirty? It’s alright in Paris, but here? No way! It’s alright in Bad Ischl too. Which just goes to show how unfathomable the locals are in their stubbornness.

Some traditional events also border on illegality, like Krampus Day, when the eponymous horned figure punishes badly behaved children by striking them with birch rods. Nowadays, in many areas word has spread that it’s actually illegal to hit your kids, but for several years mine were absolutely fascinated by Krampus, who exists somewhere between mythological anarchy and toxic pedagogy. On the one hand they were terrified of his intimidating helpers who could deliver quite a blow with their birch rods. But on the other they enjoyed the test of courage: on 5 December they would venture into town to taunt Krampus and co from afar before and then scarper as fast as they could.

The highpoint of institutionalised anarchy is the logical contradictio in adjecto that is the annual Fasching celebration, in carnival season. Before Christmas has even arrived, middle-aged men in particular will already be getting glassyeyed at the very thought of the joy and lust of the upcoming Fasching. Because that’s when they get to spend three days being what they find totally wrong the rest of the year: noisy and rude. For three days they can be all the things they moan about at their local the rest of the time: Arabian princes, travellers or even transgender people. Whatever next?!

At Fasching, super-serious men will suddenly be seen staggering about in long, blond wigs and women’s clothes, holding a cigarette in their right hand and a bottle of beer in their left; meanwhile normally “decent” women will indulge in the kind of promiscuity that is usually the preserve of males. The rag procession of Fetzen Monday in Ebensee was not properly appreciated by the US army either, who in 1946 responded to the seemingly threatening mob by deploying a heavily armed unit to keep things under control.

ALCOHOL, NOT ANARCHY

Most of the time, though, Fasching happens on the beer-and-booze side of the not-always-clear delineation between emotion and sentimentality, where there’s murky emotionality rather than clarity of the heart, and alcohol rather than anarchy.

Sometimes, however, the people of Salzkammergut are demonstratively law-abiding. Beside a junction at the far end of the Almtal valley there’s a sign that always makes me smile. It stands in a place where, from this point on, there’s nothing but animals, mountains, lakes, forests and streams. There, written in big letters, is the polite reminder: “No noise and no littering, please!” Anarchy, yes. But certainly not here in our beautiful countryside. ■

►Customs 26Queer 182Clubs and Societies 234Bird Story 240

Attersee

Attersee

Gerhard Haderer

Caricature of a majestic lake that basks in the glory of its connections to Klimt, Mahler & co and whose shores are now barely accessible to the general public. ■

Susie won’t eat t’soup.

T’soup be too sweet fah ah.

Tell ah to eat t’sauce then.

T’sauce be too sour fah ah.

Or too caud.

What’s too caud fah Susie?

T’sauce.

Tell ah t’ put it in t’sun then.

Upper Austrians.

Definitely.

►Customs 26The Salzburg Connection 192Clubs and Societies 234

Der Berg spricht

The Mountain that Speaks

Hans Reschreiter and Kerstin Kowarik

What the history of salt mining in Hallstatt tellsus about 7,000-plus years of human history,and trade and migration as a powerhouse ofcivilisation over the ages.

The Salzberg (“salt mountain”) in Hallstatt speaks – and tells its own unique stories. It speaks of how it rose from the oceans over 250 million years ago, and of the last several millennia. Listening to it is easy because there’s nothing there to distract you. A hundred metres under the ground, it’s almost completely silent. Here and there the murmurs of the giant ventilators can be heard that keep fresh air moving through the mountain, but other than that, it’s quiet. Unusually quiet. As you listen to the mountain and its tales, your concentration is heightened not just by the silence but also by the absence of mobile telephony and internet reception.

And then there’s the all-enveloping darkness. The only light is the beam from your headlamp. Not even out of the corner of your eye do you see any kind of distraction, focusing purely on what’s under your own spotlight. It’s a very special place, a place where you can listen closely to what the mountain has to say and make out the stories it tells about the miners who have worked there over the last few thousand years.

THE SALZBERG – A TIME CAPSULE

Archaeologists from the Natural History Museum in Vienna and miners from the company Salinen Austria AG have been going into the Salzberg in Hallstatt together for more than 60 years. They go to listen not to a normal mountain but to the oldest rock-salt mine in the world, for research. People have been mining salt here for 7,000 years – and still do today. Thanks to its unique salt production, the Salzberg mine in Hallstatt is the epicentre of the oldest stillactive industrial and cultural landscape in the world: the Salzkammergut.

The mountain tells its story in extraordinary detail. Everything that’s been left behind in the tunnels and massive rooms over thousands of years by miners going about their work has been preserved by the salt and remains pristine to this day. So, the Salzberg is like a time capsule, a place where time stands still. To be in the middle of a space like this and sense the unchanged traces of the millennia feels truly special, and comparable experiences can be found in just a small number of rock-salt mines around the world: the Dürrnberg mountain of Hallein in Austria, Chehrabad in northwest Iran and Duzdaği in Azerbaijan.

3,000-year-old wooden steps in the salt mine at Hallstatt. Their construction and state of preservation are unique worldwide.

UNIQUE WORLDWIDE AND SURPRISINGLY SUSTAINABLE

The many countless tools, equipment and expendable items that lie preserved in the Salzberg paint a vivid picture of the mining world in the Bronze Age and the Hallstatt period. The miners’ activities and lives can be reconstructed and regularly offer surprises. 3,000 years ago miners were perfectly organised and set up an infrastructure that would last for several generations using high-quality, specially crafted equipment. Bronze Age miners would use sophisticated stairway constructions and transport sacks unlike anything seen anywhere else in the world. And even longer ago, they were already digging down to extraordinary depths, requiring vast amounts of wood to support the tunnels and shafts, make tools and produce spills to illuminate the mine. But although the mines used so much wood, the foresters of Hallstatt were able to manage their land sustainably, accepting the limitations of the landscape – as they do to this day. Unlike copper mines around that time, which ruthlessly exploited the land and destroyed their own resources, Hallstatt remains an absolute pioneer in the field of sustainability.

HALLSTATT – THE NAME OF AN ENTIRE ERA

In pre-historic times mining operations in Hallstatt were disrupted by several massive landslides – another story the mountain tells. 100 metres under the ground entire trees can be found, roots and all, along with still-green tussocks of grass washed into the mountain by the moving earth. Every time a disruptive event like this happened, the miners would start afresh afterwards. Around 700 BC – by which time iron had been discovered, in an epoch the archaeologists have now named the Hallstatt period – mining operations became more extensive than anything that had gone before. Miners drove chambers into the mountain that were over 300 metres long and could reach heights of over 20 metres – roughly the size of a seven-storey building. Hallstatt became the biggest known mine in pre-literary history worldwide.

Thanks to its salt, Hallstatt also grew into one of the richest communities in central Europe, as is evidenced by the extraordinary grave goods in the cemetery on the Salzberg. Examinations of the wear and tear on skeletons there show that, for all the incredible wealth, everyone was made to toil: children, young people, women and men were all labourers in salt production.

WEALTH FROM SALT PRODUCTION AND CONNECTIONS

So vast were the mining chambers of the Bronze Age and Hallstatt period that they were able to produce well over a tonne of salt per day. But output of these dimensions required a highly efficient transport network in and around Hallstatt, so from 1000 BC a system connecting a series of hubs across the landscape was established – and it worked to perfection. European trade routes were not just used to distribute salt, however; goods also travelled in the opposite direction, towards the mines in Hallstatt, as major centres of production are always centres of consumption too. Around the Salzberg, logistical feats were performed. The sizable mining community was reliably supplied with vast quantities of food, tools, equipment, clothes and consumables, such as spills for lighting and pick handles. Also finding their way into the narrow Salzberg valley were amber from the north, ivory from Africa and luxury foods, such as wine from Slovenia and northern Italy, and walnuts and snails from the south.

Over many centuries – and indeed millennia – the network around salt and the foods, operating tools and transport needed for its production gave rise to an all-embracing and fully connected production and transport landscape. The entire population, every farm animal and all the usable land, forests and waterways operated for a single common goal: the production and transportation of salt.

To understand the impact, across millennia, of intensive land use for the production and transportation of salt, just listening to the Salzberg is not enough. Further traces of environmental change are found in the layers of sediment at the bottom of the lakes and bogs of the Salzkammergut. They have been the subject of research for many years and reveal that the salt network was built to be not just sustainable but also stable enough in terms of its organisation to withstand climate changes, natural disasters and political and social transformations over many thousands of years.

LEARNING FROM THE PAST TO BUILD A BETTER FUTURE

By listening to the Salzberg and the ground of Salzkammergut, we can learn not only about the past but also about how intensive agriculture and near-industrial mining can continue sustainably for incredibly long periods and networks can be structured to meet the most diverse challenges. In times of war, and of environmental, climate and resource crises in particular, this knowledge will be essential to us. Archaeology can be research for the future: to learn from the past, understand the present better and make a meaningful contribution to shaping what lies ahead.

Inside the Salzberg and in the ground of the Salzkammergut, countless secrets and wisdom lie buried. Some have already been revealed and can now be enjoyed in museums across the region or in the Salzwelten (“Salt Worlds”) of Hallstatt. And as techniques and technologies continue to improve, we can listen even more closely to the mountain. There will be plenty to hear in the years to come! ■

►Cum grano salis 30The Emperor’s Riches 118Circular Economy 135

Bernhard, Thomas

Bernhard, Thomas

Rudolf Habringer

A satirical dramoletin three stops

STOP 1: THOMAS BERNHARD RETURNS FROM THE DEAD

Sensational return to Austria

Gmunden, Ohlsdorf. (Salzkammergut Rundschau newspaper, APA)The entire literary world is in turmoil. In the summer of 2004, more than fifteen years after his alleged death, the Austrian writer Thomas Bernhard will be returning to his home in Upper Austria for a few weeks, it was announced a few days ago. According to a communique by the Upper Austrian government, Bernhard – who officially died in 1989 in Gmunden and was interred in Vienna – had retired to a remote finca on the Balearic Island of Mallorca for “health and artistic” reasons and spent the twilight years of his life there. During his time on the Mediterranean island, he is said to have produced a series of literary works that will be presented to the public on his return to the Traunsee region. It is unclear whether the author will appeal for the annulment of his will on returning to Austria.

According to their initial statements, the governor of Upper Austria and the Salzkammergut Tourism Association have responded “with pride and delight to the news that one of the literary greats of this country will return home”. In 2004 the Salzkammergut’s summer programme of culture and events will centre entirely on Thomas Bernhard.

STOP 2: THOMAS BERNHARD’S FIRST MALLORCA TEXT DISCOVERED

From the secret files of the Salzkammergut Tourism Association:

10 May, Note to the fileThe first draft from the office of Mr Bernhard was presented today. Please find enclosed the full text.

Gmunden. A Censure.Gmunden is the most beautiful place I have ever seen. But it is also the shabbiest. In fact, the whole area frightens me. What frightens me even more is the town, which is populated by very small, stocky alpine individuals who can only be described as moronic. No taller than 1.60 m on average, they stagger about the streets, populating the esplanade in a frenzy around Liebstatt Sunday every year at the end of Lent. Without exception their feet are clad in hobnail boots crafted in Goisern and their heads – by decree of the Mayor! – in grey felt hats. And when it rains, the inhabitants of Gmunden all run around in those ghastly green coats with pelerines.

Every weekend the Gmunden-folk set out in their droves and climb the Traunstein. Not a Sunday passes without a walk or an ascent of the Traunstein, whatever the weather. So unrelenting is their state of mind that it inevitably leads to devastating and ultimately fatal disasters. Imagine myriad Gmundeners setting off every weekend to climb the Traunstein, only for a few hundred of them to be fished out of the Lake Traunsee the next day, their bloated corpses washed ashore. Whole streets of them. In the summer they fall down the Traunstein, in the winter they fall through the thin ice on the lake and drown. Or, if they can fight their way to the other end of the lake, they are killed by the townsfolk of Ebensee, who are known for their violent tendencies. It’s a brutal place where murder and manslaughter, assault and fornication, treachery and cunning top the list of atrocities. Here, everything is party-political. Because that’s all there is. Everyone is either Conservative or right-wing, Catholic or Nazi, or both at the same time. Anything else is not tolerated.

I swore to myself that never, ever would Gmunden society or the betrayal of Schloss Orth castle have anything more to do with my work or, therefore, with my life. Now, after almost fifteen years to reflect and recover, I have returned to this place to find that my last will and testament has been shamelessly breached, my private home obscenely turned into a museum, and my life’s work degraded to kitsch, run down by tourist organisations for industrial use and “pinkified” in the festival colour.

Isabella Kohlhuber’s artwork Aus dem Gesetz (“From The Law”), 2016

Note to the file of the Salzkammergut Tourism AssociationThomas Bernhard’s prose piece Gmunden. A Censure can only be considered inexpedient and counterproductive to the idea of attracting tourists to stay in our beautiful destination. The Tourism Association is unable to accept this version of the text for public consumption. We hereby request that it is revised and corrected as soon as possible to present in a more positive light the key aspects of tourism in Salzkammergut (such as scenery, town, festival, castle hotel).Our decision will be forwarded to the office of Mr Bernhard for information. (…)

STOP 3: THOMAS BERNHARD’S SECOND MALLORCA TEXT DISCOVERED

From the secret files of the Salzkammergut Tourism Association:

9 June, Note to the fileToday a second, revised version of the Gmunden text has been presented. The Salzkammergut Tourism Association has unanimously approved the text for publication. It now reads as follows:

Gmunden. A Revelation.

Gmunden is the most beautiful place I have ever seen. And it is also the most perfect. In fact, the whole area is splendid, I find. What’s even more splendid is the town, which is populated by very tall individuals with intellectual minds who can only be described as cosmopolitan. Without exception their feet are clad in hobnail boots crafted in Goisern and their heads – thanks to the Mayor! – in grey felt hats. And when it rains, the inhabitants of Gmunden don their splendid green coats with pelerines, which are typical of this region.

This town is incessantly visited and admired by art-lovers from around the world. It incessantly exudes an aura of art, music, literature. Incessantly there prevails an atmosphere of lightness and absolute concentration on the arts. And incessantly, the town successfully masters the art of absolute concentration on the arts and thus the highest art of concentration on the arts. For intellectuals, the festival town on the shores of Lake Traunsee is no less than the pinnacle of achievement in the arts. And that is the truth.

Every weekend the Gmunden-folk set out in their droves and climb the Traunstein. Not a Sunday passes without a walk or an ascent of the Traunstein, whatever the weather. Splendid is the physical state of mind that leads so inevitably and regularly to outstanding and ultimately epoch-defining existential and physical achievements. This place is unlike anything that can be found anywhere else. It is different in every respect.

Whereas in other parts of Austria, everything is party-political, Gmunden feels as though it is not even in Austria. Whereas in other parts of Austria, everyone is either Conservative or right-wing, Catholic or Nazi, or both at the same time, such unculturedness is not tolerated here in Gmunden.

Now, after almost fifteen years to reflect and recover, I return to this place to find that my private home has been turned into a museum in an exemplary fashion and my life’s work developed into an epoch-defining oeuvre used for intellectual and scientific purposes. ■

►Once Upon a Time 56Film Worlds 74Ceramics 122Sooo Beautiful! 150The Forgotten Salon 236

...

Ende der Leseprobe

Der Verlag behält sich die Verwertung der urheberrechtlich geschützten Inhalte dieses Werkes für Zwecke des Text- und Data-Minings nach § 44 b UrhG ausdrücklich vor. Jegliche unbefugte Nutzung ist hiermit ausgeschlossen.

COPYRIGHT NOTICE

The publisher expressly reserves the right to use the contents of this work that are protected by copyright for the purpose of text and data mining in accordance with Section 44 b of German copyright law [Urheberrechtsgesetz – UrhG]. Any unauthorised use is hereby excluded.

The publisher has endeavoured to locate all copyright owners. When this has not proved possible in individual cases, the publisher will pay remuneration for justified claims in line with customary practice in the sector.

Copyright Prestel Verlag,

Munich · London · New York, 2024

in der Penguin Random House Verlagsgruppe GmbH,

Neumarkter Strasse 28, 81673 München

Edited by Julia Kospach and Elisabeth Schweeger for European Capital of Culture Bad Ischl Salzkammergut 2024.

Project coordination for the publication, dramaturgefor the European Capital of Culture Bad Ischl Salzkammergut2024: Jana Lüthje

Translated from German (unless indicated otherwise) by:Melanie Girdlestone, wordweaver.de

Edited by: Barbara Holland

Coordinated by: booklab GmbH, München

Lithography by: Regg Media GmbH, Munich

Cover design by: Büro Jorge Schmidt, Munich

Design and typesetting: Büro Jorge Schmidt, Munich

ISBN 978-3-641-32044-7V001

www.prestel.de