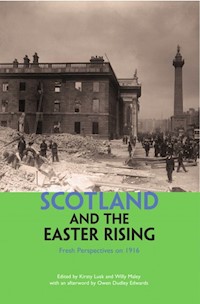

Scotland and the Easter Rising E-Book

Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Luath Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

The story of the Rising is still being told, and in these pages the reader will find much to ponder, much to discuss, and much to disagree with. From the Introduction by Kirsty Lusk and Willy Maley On Easter Monday 1916, leaders of a rebellion against British rule over Ireland proclaimed the establishment of an Irish Republic. Lasting only six days before surrender to the British, this landmark event nevertheless laid the foundations for Ireland's violent path to Independence. It is little known that James Connolly, one of the rebellion's leaders, was born in Edinburgh's Cowgate, at the time nicknamed 'Little Ireland', or that another key figure in the events of Easter 1916 was a young woman from Coatbridge, Margaret Skinnider. These and other surprising Scottish connections are explored in Scotland and the Easter Rising, as Kirsty Lusk and Willy Maley gather together a rich grouping of writers, journalists and academics to examine, for the first time, the Scottish dimension to the events of 1916 and its continued resonance in Scotland today. ALLAN ARMSTRONG • RICHARD BARLOW • IAN BELL • ALAN BISSETT • JOSEPH M. BRADLEY • RAY BURNETT • STUART CHRISTIE • HELEN CLARK • MARIA-DANIELLA DICK • DES DILLON • PETER GEOGHEGAN • PEARSE HUTCHINSON • SHAUN KAVANAGH • BILLY KAY • PHIL KELLY • AARON KELLY • JAMES KELMAN • KIRSTY LUSK • KEVIN MCKENNA • WILLY MALEY • NIALL O'GALLAGHER • ALISON O'MALLEY-YOUNGER • ALAN RIACH • KEVIN ROONEY • MICHAEL SHAW • IRVINE WELSH • OWEN DUDLEY EDWARDS Featuring a mix of memoir, essays, poetry and fiction this book provides a thought-provoking and necessary negotiation of historical and contemporary Irish-Scottish relations, and explores the Easter Rising's intersections with other movements, from Women's Suffrage to the 2014 Scottish Independence Referendum.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 433

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Scotland and the Easter Rising

Scotland and the Easter Rising

Fresh perspectives on1916

edited by

KIRSTY LUSK and WILLY MALEY

with an Afterword by

OWEN DUDLEY EDWARDS

First published 2016

ISBN: 978-1-910745-36-6

eISBN: 978-1-910324-79-0

The authors’ right to be identified as author of this book

under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 has been asserted.

© the contributors 2016

This book is dedicated to the memory and the mind of Ian Bell, who passed into history as this collection was going to press, and whose last words of the piece he wrote for this volume may stand as an epitaph of sorts: ‘But silence, as my grandmother knew, falls away in time. Then you must speak for yourself.’ We are left to contend with his silence now, to learn from his words and wisdom, and to speak for ourselves.

Contents

Acknowledgements

Timeline

Introduction

KIRSTY LUSK AND WILLY MALEY

Not only was the Easter Rising an attempt at declaring Irish independence from Britain, it was also a statement of equality and equal suffrage for women and the first attempt to assert a Socialist Republic.

To Shake the Union: The 1916 Rising, Scotland and the World Today

ALLAN ARMSTRONG

The words of James Connolly proved to be remarkably prophetic. In ‘Labour and the Proposed Partition of Ireland’ Connolly warned there would be ‘a carnival of reaction both North and South’, if the uk state was able to impose such a settlement.

The Shirt that was on Connolly: Sorley MacLean and the Easter Rising

RICHARD BARLOW

For the Scottish Gael Sorley MacLean, the ghostly attendance of Connolly is affirmed through his absence and the ‘red rusty stain’ forms a nexus of some of the poet’s great themes: wartime heroism, Marxism, and the fate of the Gaelic world.

Connolly and Independence

IAN BELL

I don’t remember his name being mentioned during the long argument that preceded Scotland’s independence referendum in September 2014… The fact remains that when it mattered most his birthplace excluded Connolly yet again.

A Terrible Beauty

ALAN BISSETT

Da, says Chelsea. This is the best experience ay ma life. Look at it. Scotland’s wakin up, Da. Scotland’s wakin up!

Who Fears to Speak?

JOSEPH M BRADLEY

Few in Scotland have heard of Irish-born Padraic Pearse and Englishborn Tom Clarke, two of the seven signatories to the historic Easter Proclamation, and seven who form half of the 14 executed by British Army firing squads in its immediate wake.

‘They will never understand why I am here’: The Irony of Connolly’s Scottish Connections

RAY BURNETT

Partly in terms of content, and entirely in terms of method, Connolly’s explicitly ‘land and labour’ approach to the lessons of the past had direct relevance to Scotland.

Anti-imperialist Insurrection

STUART CHRISTIE

Despite the heroic attempts by Connolly, Larkin and their comrades of the ICA on Easter Monday 1916 to break the alliances between the financial circles of Ireland and the British Empire and establish a genuinely worker-friendly democratic socialist Republic, by 1923 the links between those countries’ ruling elites remained unbroken and the hopes and dreams of the men and women who sacrificed their lives for a new Ireland had been hopelessly corrupted, and their ideals abused and manipulated out of all realistic shape.

Commemorating Connolly in 1986

HELEN CLARK

Not all visits however were welcome; some young men stormed in, and wanted to know the name of the person who set up the exhibition so they could ‘fill them in’. On a similar note, in the People’s Story Museum we have a panel with a photo of James and Lillie Connolly with their daughters Mona and Nora. This photo was slashed with a knife in about 1992.

The Behans: Rebels of a Century

MARIA-DANIELLA DICK

In addition to Connolly, there would be another Irish-Scottish connection for the Behans. If they had been connected through republican and socialist politics to one Scotsman, they were also to take those politics to Scotland.

After Easter

DES DILLON

Liberty. Rising. James Connolly tied to a chair. Sinn Féin rebels whispering partition. Civil War.

Margaret Skinnider and Me

PETER GEOGHEGAN

Margaret Skinnider never appeared in the history books that I devoured as a lank-haired teenager in Longford. I had never heard her name until I started going to Coatbridge in 2014, ahead of the independence referendum.

A Beautiful Thing Wronged

PEARSE HUTCHINSON

I want to wear an Easter Lily in honour of Pearse and Connolly and all their comrades; of my father and mother and all the other sacrifices; of all the suffering generations – Black and Basque and Irish.

Home Rule, Sinn Féin and the Irish Republican Movement in Greenock

SHAUN KAVANAGH

The Easter Rising and its aftermath, like the Great Famine, became embedded within the psyche of the Greenock-Irish enclave, whether Irish-born or not. It was a lasting reminder of their roots, and their ‘curious middle place’ between a Scottish and Irish Catholic identity.

Homecoming

BILLY KAY

To me, as a Scottish nationalist, identifying with 1916 and the successful independence struggle of a fellow Celtic nation was the most natural thing in the world.

James Connolly’s Stations

PHIL KELLY and AARON KELLY

1916 instructs that full democratic equality requires those who want and need it to fight on and to fight hard against the grinding, obdurate violence of the world.

A Slant on Connolly and the Scotch Ideas

JAMES KELMAN

Essential strands of our history are not generally accessed through popular media and ordinary educational resources. We contend with sectarianism, racism and assorted prejudice; historical misrepresentation, disinformation, falsification, and occasional outright lies, alongside everyday British State propaganda.

Short Skirts, Strong Boots and a Revolver: Scotland and the Women of 1916

KIRSTY LUSK

By bringing female voices back into the narrative of the Easter Rising perhaps it will be possible to take a step towards reconciliation and a fuller understanding of the importance of its legacy for Scotland today.

Irish Kin under Scottish Skin

KEVIN MCKENNA

Ireland has been the mother who gave me up for adoption and I have been the reluctant son, torn between love and resentment. Such is the contradictory love-hate relationship my generation of Scots-Irish has with the old country.

‘Pure James Connolly’: From Cowgate to Clydeside

WILLY MALEY

Those whose families left Ireland in the wake of Famine feel part of a great diaspora, and thus entitled to self-describe as Irish. Many Irish and Scottish socialists had cross-cultural connections and cross-water connections.

‘Mad, Motiveless and Meaningless’? The Dundee Irish and the Easter Rising

RICHARD B MCCREADY

The Easter Rising in 1916 was one of the pivotal events in modern Irish history. Its effects and the events after it had a profound effect not just on Ireland but also on the rest of the United Kingdom. The Rising and subsequent events had a lasting impact on the Irish Diaspora, not least in Dundee.

MacLean in the Museum: James Connolly and ‘Àrd-Mhusaeum na h-Èireann’

NIALL O’GALLAGHER

An Irish revolutionary from an Edinburgh slum, Connolly was an important figure throughout MacLean’s career. The poet’s fullest tribute to the leader of the 1916 Rising had to wait until the 1970s, the decade in which MacLean’s earlier work was republished with facing English translations, the decade in which Scottish nationalism became a serious political force and in which bloodshed in Ireland reached levels not seen for decades.

Scotland is my home, but Ireland my country: The Border Crossing Women of 1916

ALISON O’MALLEY-YOUNGER

While Pearse’s messianic rhetoric appears to mark the Easter Rising as a solely male affair, an expanding body of scholarship has shown that women, across a variety of classes and ranks were key participants in the events of 1916.

To Rise for a Life Worth Having

ALAN RIACH

Easter 1916 recollected may be a reminder of failure, violence, bloodshed, vicious state reprisal, and how public sympathies change, but in a broader context, and in more intimate ways, it may also be an enactment of virtues: different co-ordinate points, strengths, suppleness and subtlety, loyalty, determination, hope: a play, a drama, a weathering of storm, coming to rest in the prospect of a future, in Scotland as in Ireland, most apt for 2016.

‘Let the People Sing’: Rebel Songs, the Rising, and Remembrance

KEVIN ROONEY

Those preparing to celebrate the centenary of the Easter Rising should seize on this occasion to show a new tolerance. James Connolly could, if we allowed him, be a unifying figure in present-day Scotland.

Before the Rising: Home Rule and the Celtic Revival

MICHAEL SHAW

Arthur Conan Doyle, a Scot of Irish descent and twice a candidate for the Liberal Unionists in Scotland, made a striking conversion to the cause of Irish Home Rule in 1911, influenced by his friend Roger Casement, on whose behalf he petitioned the British Prime Minister in 1916.

‘Hibernian’s most famous supporter’

IRVINE WELSH

It seemed important to him that she knew that Connolly was a socialist, not an Irish nationalist. – In this city we know nothing about our real identity, he said passionately, – it’s all imposed on us.

Afterword: Scotland 2015 and Ireland 1916

OWEN DUDLEY EDWARDS

The Irish past summons us provided we keep it as tutor not as jailer. The Scottish future can remain one of ideals provided we blunt their agency for hurt.

Contributors

Endnotes

Acknowledgements

The editors wish to thank the following for their invaluable help with this book: Dermot Bolger, Pat Bourne, Stephen Coyle, Owen Dudley Edwards, Ellen Howley and Gavin MacDougall. A collection like this depends above all on the quality of its contributions, so we also wish to thank our contributors for the range and richness of their submissions and for the passion and enthusiasm they showed for the project. The editors wish to extend a special and heartfelt thanks to Lotte Mitchell Reford and Jennie Renton at Luath, whose heroic efforts in getting this book into print provided the perfect finish to what was a collective effort from the start. Their voices are a vital part of this volume too.

Timeline

1792 – Thomas Muir speaks to convention of Scottish societies sympathetic to the French Revolution, reading an address from the United Irishmen, is soon arrested and eventually sentenced to transportation.

1820 –Weaver Andrew Hardie is executed at the culmination of the 1820 Glasgow Rising.

1845–9 –Potato blight causes Famine in Ireland and prompts mass emigration around the world, including Scotland. Between 1841 and 1851, the Irish population decreased by 20% with over 80,000 Irish people coming to Scotland over this ten-year period. By 1851 7.2% of Scotland’s population was Irish-born.

1848 –Fifteen thousand Chartist radicals gather at Calton Hill to protest the arrest of two of their leaders.

1865 –Greenock Irish National Association founded.

1868 –June: James Connolly born to Irish parents in Edinburgh.

1882 –James Connolly joins the British army, lying about his age. He deserts seven years later in 1889, and marries Lillie Reynolds.

1888 –Scottish Labour party founded by RB Cunninghame Graham and Keir Hardie.

1889 –July: Charles Stewart Parnell makes his first political visit to Scotland and is made a Freeman of Edinburgh. Parnell makes a public speech on Calton Hill.

1890 –James Connolly joins the Scottish Socialist Federation.

1891 –October: Constitutional nationalism suffers a severe setback with the death of Charles Stewart Parnell, after corrosive split.

1892 –May: Margaret Skinnider born to Irish parents in Coatbridge.

November: James Connolly joins Scottish Labour Party.

1893 –Nora Connolly, second child to James and Lillie Connolly, is born in Edinburgh.

1894–5 –James Connolly stands twice for elections to Edinburgh Council. He is unsuccessful on both occasions.

1895 –First Gaelic League branch outside of Ireland is formed in Glasgow. The Pádraig Pearse branch remains active in 2016.

1896 –May:James Connolly moves to Dublin with his wife Lillie and takes a job as a secretary of the Dublin Socialist Club.

1902 –June: Patrick Pearse visits Glasgow to give an Irish Language lecture on 8 June. It is his second visit to the city, the first being in 1899.

1903 –Sean Mac Diarmada, one of the seven signatories of the Proclamation of the Irish Republic, moves to Edinburgh for work. He returns to Ireland before the end of the year. Mac Diarmada would go on to become the contact point for Glasgow Volunteers prior to the Rising.

1905 –November: abstentionist nationalist party, Sinn Féin (We Ourselves), is established.

1912 –April:Third Home Rule Billintroduced to Parliament which would establish an Irish parliament to deal with Irish affairs. The bill is due to come into effect in 1914.

May:James Connolly proposes the establishment of an Irish Labour Party at the annual trade union conference. The motion passes 49 votes to 19.

September: Over 500,000 Irish Ulster Unionists sign the Ulster Covenant pledging to block any attempts to implement Home Rule. Anybody who could prove they were born in Ulster could sign: around 2000 signatures from England and Wales.

1913 – January:Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) established to prevent the introduction of Home Rule.

August: Organised by Jim Larkin, founder of the Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union (ITGWU), and James Connolly, thousands of workers across Dublin go on strike for improved conditions and better pay. This event, known as the Dublin Lockout, lasts five months until January 1914.

September: James Connolly, in prison for his part in the Dublin Lockout, goes on hunger strike.

November: Connolly, along with Jack White and Jim Larkin, establishes the Irish Citizen Army (ICA) to protect striking workers.

11 November: First meeting of the Irish Volunteers, formed in response to the UVF in order to protect the Irish people.

1914 –April: Cumann na nBan (The Women’s League) founded as a volunteer force for women to work with the Irish Volunteers.

July: 900 rifles are landed at Howth by theAsgard. Nora and Ina Connolly participate in their dispersal. Later that day, the King’s Own Scottish Borderers shoot four civilians on Bachelor’s Walk.

August: Britain declares war on Germany. Scotland sends 690,000 men to the front. Home Rule Bill is postponed for the duration of World War I.

September: The 1914 Home Rule Act is passed. With the outbreak of WWI it is postponed for minimum of 12 months. As war continues beyond 1915, the Act does not come into force and is eventually replaced with Government of Ireland Act in 1920.

1915 –February: Scottish politicianJohn Campbell Hamilton-Gordon, 1st Marquess of Aberdeen and Temair, resigns from his second term as Lord Lieutenant of Ireland.

May–September: Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB), a republican organisation established in 1858 to fight for Irish Independence, establish a military council. Believing, with the outbreak of war, that ‘England’s difficulty is Ireland’s opportunity’, they begin planning a Rebellion.

December: Having joined the recently formed Glasgow branch of Cumann na nBan, Margaret Skinnider travels to Ireland smuggling bomb-making equipment under her hat, at the invitation of Countess Markievicz. Irish Volunteers from Glasgow are regularly smuggling weapons and explosives to Countess Markievicz and Sean Mac Diarmada in preparation for action.

1916 –January: James Connolly joins IRB military council, adding the forces of the ICA to the planned Easter Rising.

February: Conscription is introduced in Scotland. When members of the Glasgow Irish Volunteers are conscripted, they travel instead to Ireland and join the Kimmage Garrison.

April: John Maclean is imprisoned in Edinburgh Castle for sedition, where he expresses support for the Rising.

18 April: Patrick Pearse visits the Kimmage Camp to give talk to Volunteers including the Glasgow participants in the Rising. The Kimmage Garrison is 56 men strong.

21 April:The Audarrives at Tralee Bay carrying 20,000 German rifles for the Rebellion but goes unmet by leaders of the Rising.

22 April:The Audis captured by British forces. Sir Roger Casement is arrested.Eoin MacNeill, commander-in-chief of the Irish Volunteers, issues call to forces not go out on Easter Sunday as planned.

23 April (Easter Sunday): Meeting of the Military Council to discuss the situation. The Rising is put on hold until the following day.

24 April (Easter Monday): The Rising begins at noon. James Connolly commands military operations from the Headquarters at the General Post Office (GPO) throughout the week. A skilled markswoman, Margaret Skinnider takes position as a despatch rider and sniper at the Royal College of Surgeons on Stephen’s Green. TheDundee Evening Telegraphwrote: ‘Revolt in Ireland – Indications that it is spreading’.

26 April: Skinnider is shot three times attempting to set fire to houses in the nearby Harcourt Street. After the surrender Skinnider is brought to St Vincent’s hospital where she remains for several weeks. Despite being questioned by police, she is released on medical grounds and gains a permit to return to Scotland.

27 April: Connolly is severely wounded.

28 April:Charles Carrigan, an Irish Volunteer from Glasgow, is shot in Moore Street leading the charge with The O’Rahilly. It is his 34th birthday.

29 April:Leaders surrender to British army.

3 May: Glasgow Volunteer John McGallogly is court-martialed alongside Willie Pearse and sentenced to death. His sentence is repealed to life imprisonment.

3–12 May: Leaders of the Rebellion are executed by firing squad at Kilmainham Gaol over a nine-day period. This includes James Connolly who, due to his injuries, has to be tied to a chair for his execution on May 12. He is the last leader to be executed by firing squad.

June:James Connolly’s older brother, John, dies in Edinburgh and is buried with full British military honours.

August: Sir Roger Casement executed in London for treason. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle is amongst those who plead for clemency on his behalf.

Two hundred Irish revolutionaries are brought to Barlinnie Prison in Glasgow. They only remain a short period of time before being moved to Frongoch in Wales. Part of the reason is the sympathy shown to them by the Irish community and Scottish suffragettes.

December: Margaret Skinnider travels to New York, joining Nora Connolly.

1917 –Margaret Skinnider tours America speaking about the Rising and gathering support for the Republican cause. Her autobiography,Doing My Bit for Ireland, is published in New York. Before the end of the year, she returns to Dublin, taking up a teaching post.

1918 –Nora Connolly O’Brien writesThe Unbroken Tradition, her account of the events of Easter Week, while staying in New York with Margaret Skinnider.

November: End of World War I.

December: Sinn Féin wins landslide victory in Westminster elections. Members do not take up seats in Parliament. Countess Constance Markievicz is elected first female MP.

1919 –January:Sinn Féin establish an Irish government (Dáil Éßireann) in Dublin. Two days later an isolated attack on a member of the armed police force, the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC), sparks a series of violent events and guerrilla warfare which lasts three years and is known as the Irish War of Independence. During this time, Sinn Féin membership in Scotland rose to around 30,000. Margaret Skinnider is particularly active in the War throughout 1920/21.

Emergence of Irish Soviets and revolutionizing of large parts of the country.

1921 –July: A ceasefire is declared.

December: After weeks of talks and negotiations, the Anglo-Irish Treaty is signed by Michael Collins and Arthur Griffith. It allows for the establishment of an Irish Free State, although the King would remain Head of State. It also firmly establishes the border between Northern and Southern Ireland. Opinion is polarised in Ireland.

1922 –June: Due to fierce opposition to the terms of the Treaty, Civil War erupts in Ireland. During this time Margaret Skinnider works as Paymaster General for the Provisional Irish Republican Army until her arrest on 26 December for possession of a revolver and her subsequent imprisonment. Nora Connolly, James Connolly’s daughter, takes over Skinnider’s position as Paymaster General until her arrest in 1923.

December: Southern Ireland becomes the Irish Free State.

1923 –February: Margaret Skinnider goes on hunger strike in opposition to the signing of the Anglo-Irish treaty.

May: Civil war ends as Anti-Treaty forces are significantly diminished.

1925 –Margaret Skinnider is denied her military pension on grounds that it only applied to male soldiers.

1933 –The Connolly House in Dublin is attacked repeatedly, and attackers offered illicit sanction by the Church and main political parties.

1934 –April: Scottish National Party (SNP) founded with merger of the National Party of Scotland and the Scottish Party.

1936 –Communists and Socialists including James Connolly’s son Roddy and Scottish MP Willie Gallacher are assaulted at the Easter Parade on 20th anniversary of the Rising.

1938 –Skinnider is finally awarded her military pension.

1949 –April: As the Republic of Ireland Act 1948 comes into effect, Ireland becomes a fully independent nation.

1968 –June: Plaque to commemorate James Connolly’s birthplace is erected in the Cowgate, Edinburgh. Official state commemoration also included naming a train station in Dublin after him.

1971 –October:Margaret Skinnider dies in Dublin. She is buried beside famous revolutionary Countess Markievicz in Glasnevin cemetery, Dublin.

1999 –12 May: First meeting of the devolved Scottish Parliament takes place.

December:After years of unrest and violence in Northern Ireland, the Good Friday Agreement is signed, signalling a degree of peace in the North.

2014 –September: Scotland holds referendum on Independence which is rejected 55% to 45%.

2015 –May: SNP win 56 out of a potential 59 seats in an historic result in the UK General Election.

2016 –April:Centenary of the Easter Rising. Glasgow City Council is planning a memorial of the Irish Famine.

Introduction: Remembering the Rising

Kirsty Lusk and Willy Maley

Scotland and the Easter Risingis a title that will raise a few eyebrows as well as some hackles. The Rising is a defining moment in Irish history, and much of the focus in the centenary year will be on how it laid the foundations of a nation in the form of the Irish Republic. But the events of 1916 are also of enormous importance for Scotland, for the Irish in Scotland, and for Irish-Scottish relations. Edinburgh-born James Connolly was one of the leaders of the Rising, and one of the seven signatories of the Proclamation of the Irish Republic on Easter Monday, 24 April 1916. Connolly and his socialist politics were shaped in Scotland. Yet Connolly’s Scottish birth and upbringing is often reduced or overlooked in accounts of the Rising, as is his early stint in the British Army, because these are awkward facts that complicate the motivations behind the Easter Rising. With conscription in effect in Scotland and the First World War at its height, the Rising and Connolly’s involvement in it were figured in Scottish newspapers as acts of betrayal. Ironically, Connolly’s father moved to Edinburgh from the ‘Scotstown’ area of Ballybay, County Monaghan. Connolly’s motivation, background, politics and Scottish connections have yet to be thoroughly explored, or widely acknowledged, perhaps because they threaten to challenge official histories of the Rising. The part played by the diaspora is exemplified by Connolly’s presence at the heart of the Rising.

We are still coming to terms with the complexity of Irish-Scottish relations and Scotland’s role in the making of modern Ireland. That relationship was characterised by Connolly’s Clydeside contemporary, John Maclean, in the title of one of his pamphlets as The Irish Tragedy: Scotland’s Disgrace(1920). Maclean was responding to a moment of crisis and danger, when Scottish troops were being used to suppress Irish aspirations to independence. Links between the two countries are more nuanced, less negative, than the parcelling out of ‘tragedy’ and ‘disgrace’ would suggest. Indeed both Connolly and Maclean can be seen as architects of a Celtic communism committed to forging more positive and progressive bonds between these neighbour nations than the forced marriage of union and empire, with its legacy of sectarianism and its policy of divide and rule – ‘Scots steel tempered wi’ Irish fire’, in the words of Hugh MacDiarmid. The Irish-Scottish relationship has too often been viewed through an Anglo-Irish or Anglo-Scottish lens, with the dominant partner in the Union dictating the terms of debate. It is time to reconfigure that debate in Irish-Scottish terms.

The purpose of this book is to draw attention to the Scottish dimension of the Easter Rising, and to explore that dimension from a variety of perspectives. Connolly is obviously the most significant figure connecting Scotland with events in Ireland in 1916, but he is not the sole focus forScotland and the Easter Rising. Another leader of the Rising, Sean Mac Diarmada, worked as a gardener in Edinburgh in 1904. The role of Irish revolutionary groups on Clydeside in the lead-up to and during the Rising is a neglected subject, as is Scottish support for the Irish Citizen Army and the attitude of the revolutionary left, including John Maclean, to the Rising.

Not only was the Easter Rising an attempt at declaring Irish independence from Britain, it was also a statement of equality and equal suffrage for women and the first attempt to assert a Socialist Republic. Women like Coatbridge-born Margaret Skinnider, author ofDoing My Bit For Ireland(1917), played a key role in the events of Easter 1916. Born of Irish parents, Skinnider declares at the outset of her memoir of the Rising, in which she was actively engaged, ‘Scotland is my home but Ireland is my country’. The suffragettes’ struggle for women’s rights also impinged on the struggle for independence. Skinnider observed that women:

had the same right to risk our lives as the men; that in the constitution of the Irish Republic, women were on an equality to men. For the first time in history, indeed, a constitution had been written that incorporated the principle of equal suffrage.

Skinnider also mentions the support of the Scottish suffragettes for the Irishmen held in prison in Glasgow after 1916 and suggests that it was this sympathy, along with that of the Irish in Glasgow, that led to them being moved elsewhere.

Had Scotland voted Yes in 2014, it would have secured its independence in 2016, the centenary of the Easter Rising, led by a socialist republican from Edinburgh. Irish and Scottish histories have long been entwined and determined by relations with England and the British state. As that grip loosens there is the prospect once more of radical change and new connections and conversations. This book brings together a range of historians, writers and relatives of participants in order to explore Scotland’s role in the Rising and the legacy of 1916 in Scotland today. The essays and interventions gathered here are variously critical, cultural and creative; they are never cosy, comfortable or complacent. History is an open book, not a closed door. The story of the Rising is still being told, and in these pages the reader will find much to ponder, much to discuss, and much to disagree with. This collection challenges official histories of Easter 1916 by reflecting the alternative narratives that were at work within the Rising itself and presenting different perspectives on the Scottish dimension. It is also a collection that reflects on the complexity of Irish-Scottish connections today. These articles are complementary and contradictory, clashing and conciliatory, as they look from influence to legacy, from active participation to cultural commemoration, from Ireland to Scotland and back. Irish and Scottish histories have long been connected and determined by relations with the dominance of England within the British state. As that grip loosens there is the prospect once more of radical change and new connections and conversations. The questions of independence and equality raised by Easter 1916 remain relevant today, which is why remembering the Rising, in all its richness and diversity, is vital not just for the Irish in Scotland but also for Scottish civic society as a whole.

The roads towards Scottish and Irish independence have been long and are still to reach their destinations. Scotland and Ireland have a shared history of strife and played a marked role in each other’s increasing closeness to independence – as evidenced throughout this book. While the differences between their respective journeys to that goal in the past 100 years have often been figured in terms of their relationship with violence – setting the armed uprising and execution of its leaders by the military in 1916 against the constitutional referendum in Scotland in 2014 – this perspective overlooks the ways in which Ireland and Scotland are connected, their national struggles entwined in a palimpsest where influence and alteration and reaction have been key aspects. It also distracts from the remarkable similarities in the increasing national movement in Ireland of the early 20th century and Scotland in the 21st century. The roots of both can be found in not just nationalist feeling but also a driving urge to change social conditions through self-determination; in increasing gender equality; in youth engagement with politics; in the importance of the media, literature, theatre, speeches and music. In this book there are essays that respond to all these key aspects, the writers bringing their own experiences and understandings to bear on what remains a complex but critical historical event. Opening the debate and raising awareness of these different voices, there is perhaps the first step towards reconciliation, because without open discussion that will never be possible.

To Shake the Union: The 1916 Rising, Scotlandand the World Today

Allan Armstrong

ON THE 50TH anniversary of the 1916 Rising, Charles Duff, a former member of British intelligence, who had resigned in 1937 because of Foreign Office support for Franco in Spain, wrote a book entitledSix Days to Shake an Empire.The inspiration for this title came from the American socialist journalist John Reed’sTen Days that Shook the World.Written in 1919, this book had anticipated a global revolutionary transformation following the 1917 Revolution, triggered by the Bolshevik seizure of power in Petrograd in October.

By 1966, in the last year of Duff’s life, and with the benefit of hindsight, he could clearly see the ongoing break-up of the British Empire. This was recognised even by Conservative Prime Minister, Harold Macmillan in his 1960 ‘Wind of Change’ speech. However, in contrast to the thoroughly shaken British Empire, Reed’s new international revolutionary order, predicted in 1919, had not come to pass.

Yet no book has been published to argue that the 1916 Rising was ‘Six Days that Shook the Union’ – the Union in question being the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. For Reed had his sights set upon the whole world; whilst Duff limited his analysis to the ‘dissolution of the British Empire into the British Commonwealth of Nations.’ Only Ireland was ‘finally accepted in 1949 as being a “foreign country”’, which, in its ‘rather detached role… was not in the least concerned whether others followed suit or not.’

Duff was making a fairly accurate assessment of the conservative foreign policy of Sean Lemass’ Fianna Fail government in the 1960s (with the US gaining more influence at the expense of the Vatican). Meanwhile, north of the border, Terence O’Neill’s Ulster Unionist government made no attempt to challenge the UK’s own conservative foreign policy. This was also drawing the UK ever closer to the USA, as post-Second World War British governments increasingly accepted their now subordinate position in the global order. Furthermore, Irish partition was by then such an established part of the political and social landscape that even O’Neill felt he could tentatively pursue a ‘good neighbour’ policy and invite Lemass to Stormont in 1965.

Thus, Duff wrote his book before the tensions brought about in Northern Ireland by the 50th anniversary of the 1916 Rising. His book was also completed before Gwynfor Evans took the Carmarthen seat for Plaid Cymru in the 1966 by-election and fully a year before Winnie Ewing took the Hamilton seat for the SNP in the 1967 by-election. If the days marking the future of the British Empire were clearly numbered by 1966, the future of the Union still seemed secure.

Today, it is widely recognised that it was the ‘failed’ 1916 Rising, which catapulted Sinn Féin to its electoral triumph in the 1918 Westminster General Election. Sinn Féin won 73 out of 105 Irish seats. Over the next five years, the Irish Revolution was to prise 26 counties away from Westminster control, and to establish an Irish Free State recognised by the League of Nations. This Irish Revolution was very much seen as a threat to the Union.

In order to roll back this Irish Revolution, the UK state refused to recognise Sinn Féin’s electoral mandate, imprisoned members of the new Dáil, and launched a ferocious military campaign to suppress any exercise of Irish self-determination. This challenge was only eventually contained through the bloody enforcement of Partition and by providing support to the Free State forces in the Irish Civil War between 1922 and 1923. The essentials of the new British imposed partitionist settlement still remained in place in 1966. The words of a certain James Connolly proved to be remarkably prophetic. In ‘Labour and the Proposed Partition of Ireland’ (Irish Worker, 14 March 1914) Connolly warned there would be ‘a carnival of reaction both North and South’ if the UK state was able to impose such a settlement.

However, roll forward to 2016, and the Union is being shaken once more. The Scottish referendum campaign, from 2012 to 2014, brought about its own democratic revolution. 97% of those eligible registered to vote; and 85% actually voted, the highest participation rate ever recorded in electoral politics within the UK. The campaign extended from city housing schemes, long abandoned by official party politicians, to small town and village community centres throughout Scotland.

Nearly every official media outlet was on the unionist No side, including the BBC, which fell into a default defence of the word signified by its first initial. The mainstream parties, Conservative, Lib-Dem and Labour, all put aside their differences and united in Better Together to defend the Union.

The unionists were countered by Yes supporters resorting to independent media and online communication. Beyond the official SNP Yes campaign could be found the Radical Independence Campaign, Women for Independence, Asians for Independence, and even English People for Scottish Independence. The new Scottish nation being sought was not ethnic but civic, open to all who choose to live here.

Yet, as in 1916 Ireland, the Scottish campaign to exercise national self-determination was ‘defeated’. There was only a 45% Yes vote on 18 September 2014. Nevertheless, such has been the impact of Scotland’s democratic revolution that, as in 1918 Ireland, this ‘defeat’ led to an unprecedented nationalist electoral victory. The SNP took 56 out of 59 Scottish seats in the May 2015 Westminster General Election. Despite some unionist attempts to make a separate ‘Ulster’ out of the Shetlands and Orkney, even there it was a close-run thing.

So, once again, a panicked UK state, British government and the mainstream unionist parties, drawing on their long historical experience, have all been making attempts to roll back democratic revolution and to imprison it within the conservative and reactionary institutions of the UK state, particularly Westminster.

First came Lord Smith’s enquiry to sideline the empty federalist promises made by Gordon Brown during the referendum campaign. Then came Cameron’s official Con/Lib-Dem coalition response, which was to further dilute even Lord Smith’s proposals. Now, in the aftermath of the May General Election, the new aim is to ‘house train’ the SNP’s 56 MPs.

The likely consequences of such pressures can best be understood when the political and social differences between 1918 Sinn Féin and post-2015 SNP are taken into account. Although Sinn Féin sought the creation of a new Irish ruling class, drawn not from the old Ascendancy, but from the small farmers and Irish professional classes, by 1918, Sinn Féin had become openly republican and was strongly anti-British imperialist.

Today’s SNP leadership also represents a wannabe ruling class, seeking to win over Scottish business leaders, local corporate managers, as well as state and private professionals to its project. But their challenge is not so radical as Sinn Féin’s in 1918. The SNP government’s ‘Independence-Lite’ proposals accept the British monarchy, and hence the long reach of the UK state’s Crown Powers. They also accept Scottish military subordination to the British High Command and membership of NATO, and hence continued participation in US/British imperial wars.

Politically, the SNP more resembles the pre-First World War Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP). Whilst the IPP included sentimental supporters of Irish independence, in practical terms, it sought Irish Home Rule, or what today might be termed ‘Devo Max’. It accepted the continued existence of the imperial parliament at Westminster and looked for an enhanced Irish role within the British Empire.

On paper, the IPP offered no challenge either to the continuation of Westminster or the British Empire. However, a British ruling class, facing mounting economic and military (especially naval) challenges to their global supremacy, was not willing to experiment with constitutional change and come to some new accommodation with the IPP. Instead conservative unionism depended on reactionary landlords and empire-dependent business owners, particularly in the Clyde/Laggan/Mersey triangle. As a consequence, a policy of intransigence was pursued. A civil war was planned to prevent the implementation of the Third Irish Home Rule Bill in 1913–14. Significant sections of the British ruling class welcomed the First World War to avoid this prospect.

Today the SNP leadership confronts a British ruling class more tied to the City of London. Having, with some difficulty, managed their retreat from the formal Empire (as witnessed by Charles Duff in 1966), the City is very dependent on the informal ‘empire’ of global finance. Above all else, the City wants to retain its leading role in this arena. To do this, it needs the unquestioned backing of the UK state, something all the unionist parties have ensured. However, under the current ruthless global corporate order, any state that is unable to hold its territory together will soon be thrown to the dogs. Add to this the uncertainties brought about by the 2008 Financial Crash and it is easy to see why all the mainstream unionist parties are opposed to any potentially destabilising constitutional experimentation. And that goes not just for ‘Independence-Lite’, but for ‘Devo Max’ too.

Up against this, there is a limit to what can be done by 56 SNP MPs in Westminster. This is why Scotland’s democratic revolution has also been a challenge to the SNP leadership. Issues have been raised which can not be satisfied through conservative constitutionalist politics, or mild social democratic but still neo-liberal economics. This is why the SNP leadership has put a lot of effort into hoovering up all those Yes voters, and as new party members, and has tried to convert them into cheerleaders for their 56 MPs at Westminster and 64 MSPs at Holyrood.

The SNP leadership is very wary of the radicalising potential of the movement for Scottish self-determination, based on the republican principle of the ‘sovereignty of the people’. This is why they have gone back to their earlier support for the liberal reform of the existing UK constitution, based on the principle of the sovereignty of the ‘Crown-in-Parliament’. Thwarted by Miliband’s rejection of SNP overtures before the 2015 General Election, they are struggling to find liberal unionist allies at Westminster for their ‘Devo Max’ proposals.

Of course, it was mainly the horrors of the First World War that led to the drift of support from the constitutional nationalist IPP in 1914 to the now republican and anti-imperialist Sinn Féin by 1918. In this respect Scotland today’s gradual democratic revolution has been in stark contrast to Ireland’s 1916 Rising. The SNP government produced no Scottish equivalent of the 1916 Proclamation of the Irish Republic,but published itsWhite Paper, based on its ‘Independence-Lite’ proposals to be negotiated with Westminster. Instead of convening a constituent assembly to embody the sovereignty of the people, a Yes vote would have led to negotiations with Westminster. Selected unionist MSPs would have been brought into the SNP’s ‘Team Scotland’. The road to a new Scottish Free State was to be opened without Ireland’s initial republican challenge, or its subsequent counter-revolutionary clampdown.

Nobody would wish a world war to bring about the radicalisation of the struggle for national self-determination. Therefore, the issue facing us today is whether the political conditions exist which could not only shake but break the Union.

A key component of the 1916 republican coalition was James Connolly’s Irish Citizen Army (ICA). This had been born in the economic, social and political maelstrom brought about by the 1913 Dublin Lockout. In this immediate pre-war period, whilst Connolly still lived in Belfast, he promoted autonomous women’s organisation in the Irish Textile Workers Union alongside Winifred Carney (as part of the ICA, she was to join Connolly in Dublin’s General Post office in 1916). He was also a supporter of women’s suffrage, another radical movement of the time.

Furthermore, in the context of the pre-war campaign to win Irish Home Rule, Connolly was central to the development of the new Irish Labour Party (ILP). The ILP was to campaign for independent working-class interests in any new Dublin Home Rule parliament. And, along with the majority of socialists in the Second International, Connolly opposed the ever-growing warmongering of competing imperial states, especially the UK and Germany. Nevertheless, the First World War still went ahead.

Today, people are more aware of the horrors brought about by world wars. Despite the British government’s attempts to promote First World War commemorations to ease the way for more military interventions, the memory of such wars and the debacle of post-2003 Iraq make it harder for the ruling class to whip up jingoism. There is also considerably greater support today for social and national and movements based in countries suffering brutal imperial repression, such as Palestine.

Women’s suffrage was not won in the UK before the First World War. Yet who would have thought, even a decade ago, that Ireland (or 26 counties of it, anyhow) would vote for gay marriage. This has provided a new cross-border challenge to reaction in Northern Ireland, with the potential to cross the Catholic/Irish and Protestant/‘Ulster’-British divide in a way other political, economic and social movements have found it difficult to achieve.

Therefore, a political space is opening up in which we can look again at the 1916 Proclamation of the Irish Republic. However, just as James Connolly would have argued, this would not be some nationalist endpoint, but a contribution to a renewed international struggle. This was closer to John Reed’s vision than to Charles Duff’s. The Union should not only be shaken but broken, showing that Another Ireland, Another Scotland and Another World Are Possible.

The Shirt that was on Connolly: Sorley MacLean and the Easter Rising

Richard Barlow

Anns na làithean dona seo is seann leòn Uladh ’na ghaoid lionnrachaidh ’n cridhe na h-Eòrpa agus an cridhe gach Gàidheil dhan aithne gur h-e th’ ann an Gàidheal, cha d’ rinn mise ach gum facas ann an Àrd-Mhusaeum na h-Èireann spot mheirgeach ruadh na fala ’s i caran salach air an lèinidh a bha aon uair air a’ churaidh as docha leamsa dhiubh uile a sheas ri peilear no ri bèigneid no ri tancan no ri eachraidh no ri spreaghadh nam bom èitigh: an lèine bh’ air Ó Conghaile anns an Àrd-Phost-Oifis Èirinn ’s e ’g ullachadh na h-ìobairt a chuir suas e fhèin air sèithear as naoimhe na ’n Lia Fàil th’ air Cnoc na Teamhrach an Èirinn. Tha an curaidh mòr fhathast ’na shuidhe air an t-sèithear, a’ cur a’ chatha sa Phost-Oifis ’s a’ glanadh shràidean an Dùn Èideann.

In these evil days when the old wound of Ulster is a disease suppurating in the heart of Europe and in the heart of every Gael, who knows he is a Gael I have done nothing but see in the National Museum of Ireland the rusty red spot of blood, rather dirty, on the shirt that was once on the hero who is dearest to me of them all who stood against bullet or bayonet or tanks or cavalry or the bursting of frightful bombs: the shirt that was on Connolly in the General Post Office of Ireland while he was preparing the sacrifice that put himself up on a chair that is holier than the Lia Fail that is on the Hill of Tara in Ireland. The great hero is still sitting on the chair fighting the battle in the Post Office and cleaning streets in Edinburgh.

(MacLean, 270-1)

SORLEY MACLEAN / SOMHAIRLE MACGILL-EAIN’S ‘National Museum of Ireland / Ard-Mhusaeum na h-Éireann’ brings together contrasts of presence and absence, past and present, nationalism and socialism, bardic utterance and private reflection, all with a deft economy. MacLean’s poem was written in 1971 – at the height of the conflict in the north of Ireland – a year in which the poet ‘takes part in the first Cuairt nam Bàrd (‘poets’ tour’), visiting a series of locations in Ireland in the company of Colonel Eoghan Ó Néill, and receives a standing ovation at Trinity College, Dublin’ (MacLean, xlix). MacLean’s visit, combined with the ‘evil days’ of the so-called ‘Troubles’ in the North, leads to a contemplation in the poem of earlier Irish history, and the festering laceration of Ulster is connected with Connolly’s wounding in the Dublin General Post Office (GPO) in 1916 (see also the ‘tormenting wounds / cràdhte, fo chreuchdaibh’ in the poem ‘Séamas Ó Conghaile’ / ‘James Connolly’, MacLean, 442-3).1But how can the ‘old wound of Ulster / seann leòn Uladh’ be in the ‘heart of Europe / cridhe na h-Eòrpa’? Despite its north-western position in (or rather off) Europe, Ulster is the ‘heart’ of the continent for MacLean because the fate of the Gaels or what Joyce called the Celtic World’ (Joyce, 124) are absolutely central to MacLean’s concerns.

As is well known, Connolly was badly injured by a bullet during the British assault on the GPO, a location where he was commanding military operations during the Rising (MacLean’s attention to wartime bodily injury may have a biographical connection – he was seriously wounded by a mine at the Second Battle of El Alamein in 1942).2However, the ‘rusty red… rather dirty’ bloodstain on Connolly’s shirt exhibited in ‘National Museum of Ireland’ contrasts with the strange imagery of orderliness and cleansing at the poem’s close: ‘[t]he great hero is stil… cleaning streets in Edinburgh / [t]ha an curaidh mòr fhathast… a’ glanadh shràidean an Dùn Èideann’ (Connolly grew up in Edinburgh’s Cowgate, the son of Irish immigrants). Furthermore, the sacred terms used in the poem – ‘sacrifice’, ‘holier’ – effectively frame the Rising in orthodox Pearse fashion, as a noble, sanctifying ritual. Perhaps this should not be that surprising, since even the Marxist Connolly eventually began to conceive of the Rising in these terms.3Connolly’s shirt becomes, for MacLean, a quasi-religious icon, an object to be venerated. Compare ‘Calbharaigh’ / ‘Calvary’, where the poet rejects Christianity in favour of contemplating a ‘foul-smelling backland in Glasgow… where life rots as it grows / air cùil ghrod an Glaschu / far bheil an lobhadh fàis’ and on ‘a room in Edinburgh… where the diseased infant writhes and wallows till death / air seòmar an Dùn Èideann… far a bheil an naoidhean creuchdach / ri aonagraich gu bhàs’. In both poems larger or distant themes are linked to more immediate or local concerns, and, crucially, back to Scotland (here again we have MacLean presenting social and political issues with a vocabulary of disease, injury, and death).

Of course, Connolly is a heroic figure to MacLean not simply because of the Edinburgh/Scotland connection but also through the linkages of class-consciousness and anti-colonial sentiment. The poem also suggests that MacLean regards Connolly as a fellow Gael (although Pearse was the Irish language advocate of that era, not Connolly). Mainly, MacLean’s admiration is a result of Connolly’s Marxism and the action he took in the April of 1916. As Raymond Ross notes, ‘throughout MacLean’s poetry… we are confronted with images of, and references to, heroic figures whose moral or political passion is evident through action’ (Ross, 97). ‘Names like Lenin, Connolly, John Maclean etc. are more to me than the names of any poets’ MacLean once stated (MacLean, qtd in Ross, 94). MacLean’s radicalism stemmed from the history of his island and his people:

[h]is great-grandfather was the only one of his family who had not been evicted to Canada or Australia during the Raasay clearance of 1852–4, and two of his paternal uncles had been friends and fellow-workers of John Maclean, who MacLean once described as ‘the last word in honesty and courage… a terrific man’ (Black, xxix).

As Raymond Ross writes, ‘[m]uch of MacLean’s subject matter, embodying as it does a Marxist outlook, is political’ (Ross, 92).

‘National Museum of Ireland’ also demonstrates MacLean’s heavy emotional investment in Gaeldom as a whole. The attention paid to Irish and Scottish connections here and elsewhere in his work comes from MacLean’s sense of being a poetic spokesman of a specific people and community. The lines ‘every Gael… who knows he is a Gael / gach Gàidheal… dhan aithne gur h-e th’ ann an Gàidheal’ and the movement from the Dublin GPO to the streets of Edinburgh are part of this. Elsewhere, as Christopher Whyte has written, MacLean ‘envisages a kind of utopia, where the divisions between Scots and Irish are negated’ (Whyte, 73)4and his ‘utterance’ has ‘a public, bardic strain’ (Whyte, 157). Similarly, Seamus Heaney has written of hearing MacLean reading his poems in Gaelic:

this had the force of revelation: the mesmeric, heightened tone; the weathered voice coming in close from a far place; the swarm of the vowels; the surrender to the otherness of the poem; above all the sense of bardic dignity (Heaney, 2).5

And yet, as Whyte has written, the ending of ‘National Museum of Ireland’ ‘suggests that the miracle it embodies is dependent on the poem’s individual consciousness’ (Whyte, 74). The poem is an unusual synthesis of a declarative public statement and a personal, lyrical epiphany. All of this is achieved with a Modernist frugality and the kinds of ‘juxtaposition and paradox’ (Thomson, 268) utilised in theDàin do Eimhir.

MacLean’s ‘National Museum of Ireland’ is also an amalgam of a form of nationalism (if we can consider Irish and Scottish Gaeldom as a kind of ‘nation’ – at the very least the poem is an expression of a sort of communalism based on linguistic links and shared experiences of English colonialism) and of socialism, a synthesis not dissimilar to the Rising itself. The Rising can be considered, to some extent, as a synthesis of socialism and nationalism given that it relied on the merging of Connolly’s Irish Citizen Army with the Irish Volunteers and Cumann na mBan. Furthermore, the poem displays in miniature the central concerns and influences of the Scottish Literary Renaissance (SLR), of which MacLean’s earlier poetry was a crucial part: an interest in national (or Gaelic identity) and national revival as well as Irish intellectual, cultural, and political connections. There was a strong Irish influence on the SLR as whole, especially on Hugh MacDiarmid, who:

welcomed Irish immigration into Scotland, as sustaining ‘the ancient Gaelic commonwealth,’ while by 1930