Scotland the Brave? E-Book

Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Luath Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

Politics took a decisive turn twenty years ago with the birth of the modern Scottish Parliament. People in Scotland want to 'make a difference' and build a better future. Scotland the Brave? offers both an acute assessment of where we are today and a route map to the future. Editors Gerry Hassan and Simon Barrow have brought together an impressive array of Scottish and international voices to cover concerns including the economy, environment, social policy, beliefs, human rights, media and culture. After two decades of significant change, the contributors describes how wealth is created and distributed in Scotland; ways of addressing social divisions and inequality; the needs to respond to the climate emergency, as well as considering challenges to democracy. This book provides powerful, non-partisan visions for the future that indicates how we can rise to challenges of our times and truly become 'Scotland the Brave'.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 638

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

In Memory of Kenneth Roy and Ian Bell

First published 2019

ISBN: 978-1-912387-61-8

The paper used in this book is recyclable. It is made from low chlorine pulps produced in a low energy, low emission manner from renewable forests.

Printed and bound by Bell & Bain Ltd., Glasgow

Typeset in 10.5 point Sabon by Lapiz

The authors’ right to be identified as authors of this work under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 has been asserted.

© the contributors

Contents

Acknowledgements

INTRODUCTION: Scotland the Brave? Assessing the Past Twenty Years and Mapping the Future

GERRY HASSAN AND SIMON BARROW

CHAPTER 1: How Scotland Can Keep Breathing

NEAL ASCHERSON

Section One – Scotland’s Economy

CHAPTER 2: The Political Economy of Scotland Twenty Years of Consequences

CRAIG DALZELL

CHAPTER 3: The Scottish Economy, Ownership and Control

NEIL McINROY

CHAPTER 4: Breaking with Business As Usual

MIRIAM BRETT

Section Two – A Social Justice Scotland for All?

CHAPTER 5: A Socially Just Scotland?

KIRSTEIN RUMMERY

CHAPTER 6: Scottish Education Since Devolution

JAMES McENANEY

CHAPTER 7: The Early Years Are We Doing Our Best for Children from Birth to Eight?

SUE PALMER

CHAPTER 8: Higher Education and the Scottish Parliament New Players in an Old Landscape

LUCY HUNTER BLACKBURN

CHAPTER 9: Public Health Progress?

GERRY McCARTNEY

CHAPTER 10: The Catalytic Converter Twenty Years of Devolution Preserving NHS Scotland as a Nationalised Health Service

ANNE MULLIN

CHAPTER 11: Housing Policy Exposing the Limits of Devolution and Ambition

DOUGLAS ROBERTSON

CHAPTER 12: Mark and Measure Judging Scotland Through Punishment

FERGUS McNEILL

Section Three – Scotland’s Public Realm

CHAPTER 13: Making Participation About People An Exchange

JIM McCORMICK AND ANNA FOWLIE

CHAPTER 14: Banning the Box Humanity and Leadership in Scotland’s Public Services

KARYN McCLUSKEY AND ALAN SINCLAIR

CHAPTER 15: Gender, Power and Women

ANGELA O’HAGAN AND TALAT YAQOOB

CHAPTER 16: Generational Gridlock Scotland?

LAURA JONES

CHAPTER 17: Rainbow Nation A Story of Progress?

CAITLIN LOGAN

CHAPTER 18: Race Equality and Nationhood

NASAR MEER

CHAPTER 19: Managing Democracy

KATIE GALLOGY-SWAN

CHAPTER 20: The View from Constitution Street

JEMMA NEVILLE

CHAPTER 21: Scotland’s Environment Beyond the Fossil Trap Imagining a Post-Oil Scotland

MIKE SMALL

Section Four – Cultures of Imagination

CHAPTER 22: Twenty Years of the Press and Devolved Scotland

DOUGLAS FRASER

CHAPTER 23: Broadcasting in Scotland

BLAIR JENKINS

CHAPTER 24: Arts in Hard Times

RUTH WISHART

CHAPTER 25: Beyond the Macho-Cultural Scottish Literature of the Last Twenty Years

LAURA WADDELL

CHAPTER 26: The Carrying Stream Twenty Years of Traditional Music in Scotland

MAIRI MCFADYEN

CHAPTER 27: Architecture and Design

JUDE BARBER AND ANDY SUMMERS

CHAPTER 28: Scottish Football in the World of Global Money

JIM SPENCE AND DAVID GOLDBLATT

CHAPTER 29: Religion and (Beyond) Belief in Scotland

SIMON BARROW WITH RICHARD HOLLOWAY AND LESLEY ORR

Section Five – Place and Geographies

CHAPTER 30: The Land Question

ANDY WIGHTMAN

CHAPTER 31: The Place of Gaelic in Today’s Scotland

MALCOLM MACLEAN

CHAPTER 32: Edinburgh Calling

GEORGE KEREVAN

CHAPTER 33: Glasgow A Knowledge City for the Knowledge Age

BRIAN MARK EVANS

CHAPTER 34: Conversations About Our Changing Dundee

GILLIAN EASSON AND MICHAEL MARRA

CHAPTER 35: Aberdeen A City in Transition

JOHN BONE

CHAPTER 36: Life in the First Minister’s Constituency A Story of Govanhill

CATRIONA STEWART

Section Six – The Wider World

CHAPTER 37: Defending Scotland

WILLIAM WALKER

CHAPTER 38: Security Matters

ANDREW W NEAL

CHAPTER 39: Who Owns the Story of Scottish Devolution and Social Democracy?

GERRY HASSAN

CHAPTER 40: The Art of Leaving and Arriving Brexit, Scotland and Britain

FINTAN O’TOOLE

AFTERWORD: After the First Twenty Years and the Next Scotland

SIMON BARROW AND GERRY HASSAN

CONTRIBUTORS

Acknowledgements

The purpose of this book is to understand the Scotland of the past twenty years, and to do so in a way which examines society, the economy and culture, and hence, politics and power in the widest sense. In so doing we have asked contributors to assess what has changed and what has not, and to make an evaluation of where we are and future challenges.

In such an all-encompassing project, there are numerous challenges. One is the breadth and balance of contributors, mixing the established with the emerging voices. Another is in style, combining different takes and tones – from the general overview to the specific, and from the conventional essay to the conversation between two and, on one occasion, three people.

Equally challenging has been where to draw the boundaries of such an ambitious project. Hence, we have included reflections on religion, art and football – the latter of which touches on wider issues about culture, place and identity in a world of globalising capitalism. We have planned this volume so that it makes a serious contribution to contemporary Scottish history.

A project like this is, by necessity, a collective effort. First and foremost, we would like to thank the stellar range of contributors who gave their time, insights and expertise for the following pages. We often asked the impossible in terms of briefs, and in each and every case were met with encouragement and positivity.

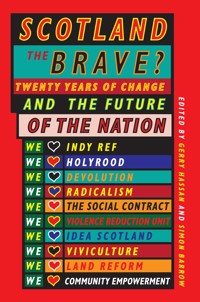

Sincere thanks are due to numerous people who gave advice in shaping this book. This includes Philip Schlesinger, Iain Macwhirter, Angela Haggerty, Peter Geoghegan, Willie Sullivan, Isabel Fraser, Madeleine Bunting, John Harris, Danny Dorling, Nigel Smith, Carol Craig, Katherine Trebeck, Joe Lafferty, Joyce McMillan, Michael Gecan, Kirsty Hughes, Mike Small, Jordan Tchilingirian, Sarah Beattie-Smith, Carla J Roth, Rosie Ilett and Vivienne Wilson. A big thanks to artist Ross Sinclair for working with us to come up with our striking cover, which succeeded in doing something different and eye-catching.

We would also like to acknowledge and thank Luath Press, Gavin MacDougall and all his staff. They have been passionate about this book and we would like to honour the wider contribution that Gavin and his team at Luath have made to the political and intellectual life of this country in recent years. They have made our public debates richer. We record our appreciation of this and our relationship with them.

Gerry Hassan

Simon Barrow

INTRODUCTION

Scotland the Brave?Assessing the Past Twenty Years and Mapping the Future

Gerry Hassan and Simon Barrow

SCOTLAND HAS CHANGED dramatically over the past twenty years. Until 1999 Scotland was governed from Westminster and for 18 years (between 1979 to 1997) by the Conservatives, elected on a minority and diminishing vote. Domestically, politics was defined by single party domination of the system in which Labour were the beneficiary, and which the SNP and Liberal Democrats occasionally shook but did not seriously challenge. By the 1997 election, a sizeable majority of public opinion had given up on the old political order and coalesced around a home rule consensus that found expression in the 74 per cent vote for a Scottish Parliament in the 1997 referendum.

The establishment of Parliament aided a dramatic shift in the country’s public affairs and ethos. Politics, voice and legitimacy that were once situated at Westminster became increasingly located at home over the next twenty years. Scotland changed in numerous other ways – from the economy, society, the public realm, place, culture to geopolitics. How Scotland has seen itself, and has been perceived by others, has shifted – aided by the movement of deep tectonic plates in each of these areas.

We are still in the midst of this change and the twentieth anniversary of the Scottish Parliament offers the opportunity to assess a Scotland beyond the narrow politics of devolution. In these pages we therefore address a wider canvas. This includes what has changed and what has not changed over this devolution era; understanding where, and how far, we have come, and what the contours and challenges of the future might look like. We review the consequences of this change, who and what have been the forces shaping it; who has gained and who has lost and assess the Scottish experience in the context of longer-term transformations here and across most of the developed world. This is a book about politics in the widest sense that touches each and every one of us in our everyday lives.

Scotland the International

The Global Picture

Scotland’s transformation over the past two decades is part of a bigger global picture and involves homegrown change. It is important to understand the impact of the former. Across the West there has been a crisis of mainstream politics: the hollowing out of and discrediting of neo-liberalism – the idea that a corrupted version of markets and rigged capitalism should be the solution to most public policy choices – combined with the retreat of moderate forces of the centre-left and social democracy.

We have also witnessed the crisis of modernity – of left, right and nearly every other persuasion – and the related idea of progress, and with it the notion that the future was always going to be better than the present. In relation to this the time honoured twentieth century methods of agency – trade unions and collectivist institutions on the left and those of traditional authority and deference on the right – have retreated in the face of individualism, economic and social change and the onward march of the market (Arrighi, 2009).

In the place of this, new voices and movements have appeared. It is now close to cliché to talk about the rise of xenophobes and populists from UKIP to France’s Front National (now National Rally), to the German AFD (Alternative für Deutschland), and the Trump phenomenon. But it is also true that other currents have emerged – Podemos in Spain, Syriza in Greece (before it had to face EU imposed austerity), the realignment of the German left and the left-wing upsurges in the British Labour Party and the US Democrats.

There has emerged the salience of identity and belonging – much of which relates to big questions and forces redefining society. Identity politics have come to be seen as critical and often fraught with battle lines on gender, sexuality, ethnicity, race and numerous other areas (Mouffe, 2018). They have become defined by charges and counter-charges with some using the assertion of their identity to find status and voice, while others have used it to claim this has all gone too far and is too atomising, precious and illiberal. What is often missed is that all politics has always, to some extent, been a form of identity politics.

These shifts have occurred against a backdrop of enormous changes in the world economy, the shaping of capitalism and how wealth and power is accumulated and exercised. Massive amounts of new wealth have become concentrated in very few hands. The Oxfam statistic reminds us that the 26 richest billionaires in the world own as much wealth as the 3.8 million people who comprise the poorer half of humanity. This is a scale of inequality that will never be redressed just by national governments, the philanthropy of the rich or ‘trickle-down’ economics (The Guardian, 21 January 2019).

At the same time, mainstream politics has struggled to address issues beyond the short-term: the electoral cycle, climate change, environmental damage, species extinction, the long-term demographics of the West and tensions around immigration and population movement. When there has never been more need for politics to involve leadership, honest conversations and taking difficult longterm decisions, it has never been so lacking. In this we have to ask: is Scotland really that different? Can we rise to the challenges of our times and can we be ‘Scotland the Brave’? And, if we answer in the affirmative what does that entail and what would it look like?

Scotland’s Journey Over the Past Twenty Years

The Scottish Parliament and devolution generated a new political environment, one which created numerous differences compared with the previous Westminster order. First, it brought democratic voice, debate and legitimacy to the heart of government – something that had been increasingly lacking.

Second, it injected accountability and scrutiny into aspects of public life that had previously been left unexamined. Sometimes formally via the Parliament, sometimes informally – through devolution acting as a catalyst in public life.

Third, it introduced a more pluralist politics, where all political parties, with the exception of the 2011 election, had to recognise and act in cognisance with the knowledge that they were popular minorities. Westminster politics and the distortions of the first past the post (FPTP) system had disguised this for decades.

Fourth, it reinforced Scottish politics as being characterised as social democratic and of the centre-left, even in the process moderating the voice of the Scottish Conservatives (at least in comparison to the direction of the British Conservatives).

Fifth, politics was further influenced by the fact that the main contestation in terms of parties and competing governments was, until the 2016 election, between Labour and the SNP. These two parties who placed themselves on the centre-left and often competed on the same terrain for the same voters.

Sixth, political debate, particularly in the first decade, became about public spending and its growth, allocation and winning extra remuneration. Even once retrenchment and austerity came, much of the political debate remained about spending and public services. This may eventually wither as the Parliament assumes more taxation powers, and more powers generally, but we have yet to see this effect.

Seventh, the establishment of a Scottish Parliament and Executive/Government led to these new institutions asserting themselves and accumulating more powers. Thus, local government faced growing constraints, while numerous public bodies underwent reorganisation that amounted to further centralisation and standardisation – a trend evident under Labour, the Liberal Democrats and the SNP.

Another dimension of devolution was that it contained within its own idea its own demise – with Scottish politics inexorably moving beyond its original parameters. The Scottish Parliament quickly became the main political institution in the country; the arrival of the Scottish Government produced an embryonic state and quasi-independence even before the momentum towards an independence referendum. At the same time, the constitutional framework of the UK struggled to adapt to and to accommodate a freshly assertive autonomy and voice north of the border.

Devolution and a New Public Space

The Scottish Parliament contributed to the creation of a new public space and stage, a new political system, and a different political culture. In this there were many continuities with the Westminster order as it manifested itself in Scotland, but it was also the birth of something new – with a dynamic and dynamism of its own.

In the course of twenty years, the Scottish Parliament and Executive/Government has established itself solidly, following a shaky start. There were the brief periods of the Donald Dewar and Henry McLeish administrations that never found their level – lacking both leadership and a sense of inner discipline, critics felt. The Jack McConnell administration stabilised the situation, but was widely viewed as uninspiring, characterised by the phrase ‘do less, better’ – hardly a clarion call to change the world.

Eventually, the new institutions found their feet, aided by the move of the Parliament from the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland in 2004 to the new Holyrood building designed by the late Enric Miralles, the Catalan architect and EMBT architects – its cost overrun was another blight in the Parliament’s early years. A significant development was the decision of the SNP, upon winning the 2007 election, to rename the Executive as the Scottish Government – a symbolic move that spoke to the nationalists’ ambition and aspirations for Scotland as a nation.

A defining characteristic of much of the SNP period in office – first under Alex Salmond and then Nicola Sturgeon – was a reputation for competence, widely acknowledged after the previous Labour-dominated era. Yet, as the years of SNP rule passed, this technocratic, managerialist approach began increasingly to be taken for granted and even discounted. Moreover, its growing limits became more apparent – particularly in light of the harsher climate of cumulative public spending constraints and Westminster imposed austerity.

Many observers started to ask: where was the radicalism, the ability to think longer-term and the willingness to ask difficult questions on a range of issues? Where was the boldness or desire for change on educational attainment, health service reform or local government taxation, for instance? Action on these and a host of other issues would create winners and losers, and hence political turbulence, which would require leadership and debate. Where in effect was the ‘Scotland the Brave’ that many people liked to think of?

The Strength of Scotland’s Social Democratic Politics

Scotland over these past two decades has adopted a distinctive political path. It could be characterised as representing a communitarian and social democratic mindset – with an emphasis, where possible, upon universality and inclusivity over selectivity and targeting. There has been an explicit reference to a ‘Scottish social contract’ which connects all of us from cradle to grave and invokes a concept of citizenship which aspires to be enlightened and progressive (The Times, 7 November 2017).

In this, there was an element of self-congratulation and over-defensiveness in the face of criticism that characterised both the Labour and SNP eras. This has seen a lack of interest in detail and the distributional consequences of decisions – such as free care for the elderly, abolition of tuition fees and the Council Tax freeze – all of which assisted those on above average incomes and penalised the poor and disadvantaged.

This centre-left sentiment left several questions unexplored. Where, for example, were the guiding lights of Scotland’s political prospectus? In terms of values these were, more often than not, beyond the official platitudes of the Government’s strategy documents. The assumption was always that public services were informed by a set of progressive, humane and compassionate grounds. But this was often more implicit and rarely fully articulated so that it could be investigated along with the relationship between values, rhetoric and reality.

How otherwise could a social contract and a social democracy be a living, evolving one which renewed, adapted and improved in light of circumstances? The two main parties of the centre-left – the SNP and Labour – have both, over the devolution era, shown a conspicuous lack of interest in rigorous, intellectual ideas.

The SNP has suffered from a dearth of original thinkers, with the obvious exception of, on domestic concerns, the late Stephen Maxwell, with his case for left-wing independence and his critique of the Scottish middle-class settlement. There were also Neil MacCormick’s ideas on post-sovereignty and the distinction between existential and utilitarian nationalisms (see Maxwell, 2012, 2013; MacCormick, 1999). Both men were part of the pre-Parliament generation, before the rise of the party’s managerialist political class.

Similarly, Labour have produced no coherent political ideas over the period – for all the interventions of Gordon Brown and Douglas Alexander as well as Henry McLeish, former First Minister (see Brown and Alexander, 1999; 2007; McLeish, 2014; 2016). The last Labour thinker in Scotland with an impressive pedigree was JP Mackintosh, academic and Labour MP for Berwick and East Lothian, whose premature death at the age of 48 in 1978, illustrated the overall paucity of thought in the party (Drucker, 1982).

A larger point is the absence over the course of the past two decades of rigorously intellectual political work. There has been lots of politics beyond thinking about the Parliament – from commentators, activists, campaigners, NGOs, academics and policy experts. But something has been noticeably missing from the public sphere and what William Mackenzie called ‘the community of the communicators’ (Mackenzie, 1978).

This is not to say that there have not been ideas and initiatives to try to frame and understand society. But there has been a lack of deeper thinking and greater ambition, along with critical analysis, which has had an impact on the public sphere. The Parliament has instead reflected a sense of deep-seated pragmatism, drawing from the existing well of centre-left politics. Alongside this it has represented a sense of being – and an expression of identity and political community – not so much in terms of the detailed actions of the Parliament, but what it stands for and the very idea of it.

Moreover, the contested site of the public sphere has included an evolving politics and sense of place which has increasingly made Scotland feel like a different country from the rest of the UK. This complex, but fragile ecology has been underlined by its setting: a ‘dualistic public sphere’ alongside a London-centred public sphere – which continues to impact Scotland and has definitely dominated the airwaves post-Brexit vote (Hassan, 2014b; Schlesinger, 2019).

Elitist Scotland vs. Egalitarian Scotland

As Scotland has grown more autonomous and diverged from the UK/RUK, aided by the inexorable right-ward drift of British politics, it has made the need for more self-reflective debates about the state of the nation even more important. Hence, beneath an inclusive, Panglossian social democratic sentiment sits a set of characteristics which demand scrutiny and action. They raise the question of whether we are truly an egalitarian nation, or just a continuation of inherited elitist practices. These include the critical issues set out below.

First, Scotland’s elite are unrepresentative and self-reproducing (as are elites in the rest of the UK) with 57 per cent of university principals and 45 per cent of senior judiciary being privately educated. This is compared with 55 per cent and 71 per cent across the UK. Our country emerged less elitist than the rest of the UK in parliamentarians: with 20 per cent of MSPs being privately educated (and 43 per cent going to one of Scotland’s four ancient universities), compared to 33 per cent for Westminster’s MPs (and 24 per cent going to Oxbridge). All figures are for 2015 (Social Mobility and Child Poverty Commission/David Hume Institute, 2015).

The aforementioned study concluded:

the top of Scottish society is significantly unrepresentative of the Scottish population – though less so than the top of British society – with almost a quarter (23 per cent) of those in the professions we looked at educated privately at secondary education level compared to just over 5 per cent of the Scottish population as a whole and almost two thirds (63 per cent) having attended an elite UK university (Social Mobility and Child Poverty Commission, 2015).

Second, over the devolution era, Scottish measurements of inequality do not show any indication of progress in tackling this blight. Take the Gini coefficient – if it equals 0 it means everyone has the same income and if it equals 1 it means one person has all the income. One study gives an overall Scandinavian average rating of 0.25 and puts Scotland at 0.30 in 1996–97 and 0.34 in 2015–16 with it remaining in the 0.30–0.34 range for the whole two decades (Scottish Government, 2017; Pryce and Le Zhang, 2018). This makes Scotland only slightly less unequal than Great Britain over the period, a difference accounted for by the London-effect. Similarly, if we look at inequality by neighbourhood, proximity to crime, air pollution and housing quality, Scotland has not been making any real progress (Pryce, op. cit.).

Third, the seismic health inequalities which have disfigured Scotland for too long continue unabated. Many figures can be used to underline this, but one produced by Save the Children is stark: a child born in 2013 in Lenzie, a suburb of Glasgow, is predicted to live 28 years longer than a child born in Calton in the east end of the city in the same year. The harsh reality of this divide is that only 8.2 miles separate these two areas, working out at a 3.4-year life expectancy gap per mile (Save the Children Fund, 2013).

Fourth, Scotland has long been marred by a culture of violence – in which there has been improvement for the better recently. The country had a state approved practice of violence against children, only banning belting in schools in 1987 (with this happening due to pressure from the European Court of Human Rights). Today, despite this change and active proposals for a ban on smacking children, 22 per cent of children are still subjected to frequent physical punishment, mostly at the behest of their parents (Marryat and Frank, 2019).

Fifth, Scotland’s record of political participation is not entirely positive in recent years. We can all be proud of the 84.6 per cent turnout in the 2014 independence referendum, but democracy is not a one-off. It is a continuous process. There has been widespread complacency among both Yes and No campaigners about the ‘missing Scotland’, and in particular the ‘missing million’ voters who had not voted in a generation having previously done so – and who turned out in the Indyref (Hassan, 2014a). Many seem to believe that this systematic exclusion has been permanently addressed by voting once in a referendum, oblivious to what has failed to come after 2014.

The reality is that Scotland’s record of political participation, as measured by the minimum of turnout at successive Scottish Parliament elections, has never been as high as Westminster. Across five Scottish elections it has ranged from 58.2 per cent in 1999, 49.4 per cent in 2003, 51.7 per cent in 2007, 50.3 per cent in 2011 and 55.6 per cent in 2016. Westminster turnout over the period 1997–2017 has been 71.3 per cent, 58.1 per cent, 60.8 per cent, 63.8 per cent, 71.1 per cent and 66.4 per cent (Curtice, 2019). Thus, Scotland has become, Indyref apart, accustomed to the politics of a truncated electorate; those who vote are more affluent, middle-class and older than the electorate overall, and non-voters are poorer and younger. This has consequences for our political debate and the choices politicians feel they can make.

These and other salutary facts need to be placed centre-stage, both in assessing the impact of devolution, but also in critically informing discussions about the route-map for the future. The Scottish Parliament has accrued more powers through the Scotland Acts of 2012 and 2016, and more are coming its way. Beyond that, the way Scotland thinks, and talks, has gone through the democratic revolution of Indyref, which certainly contributed to a wider debate about the country’s future. This should not be understood as an isolated event, with the normal service of top-down politics continuing as if nothing much had changed. But neither has it been transformational. There has been regression.

Different Scottish futures have been present in the past and have mobilised people to action. Such a vision was contained in the Labour story of Scotland in the 1950s and 1960s, with its focus on lifting up working-class people, widening opportunities and life chances. Similarly, the SNP prospectus offered in 2007 and 2011 was fundamentally future-focused. In 2007, informed by positive psychology, it emphasised the upside of a self-governing nation. Different visions of Scotland and the future were also evident in the 2014 referendum, galvanising a significant part of the Yes campaign. These mobilising stories are vital to the shape of the future which is being made in the here and now. It is to that future we now turn.

The Terrain of the Scotland of the Future

The Scotland of the future and of the next twenty years cannot, and will not, be a mere projection of today’s country. At best, the linear optimism that is the inherent message of globalisation (ie that the only version of the future possible is an enlarged version of today in consumption, goods, and markets) has to be challenged (Hassan et al, 2005). It is a faux optimism that masks a profound pessimism – the future has already been decided by the rich and powerful and the rest of us have no choice but to buckle down and accept it.

The parameters of ‘continuity Scotland’, of devolution, business as usual and of institutional capture informed by the assurances of the managerial class will not be adequate in light of pressures coming down the line. How do we collectively find a set of directions which begin to sketch out the contours of what is to come?

Answers to this will not be found solely by looking at constitutional change, whether pro-union or pro-independence. The former needs to come to terms with the fundamental shortcomings of the UK as it is. How its economy, society and culture is increasingly focused on a winner-takes-all global class centred around London and the South East, and how all of this impacts Scotland and the northern regions of England.

The pro-independence movement cannot be based on the abstract principle of ‘independence now – and let us worry about the detail later’. Apart from the fact that this offer is unlikely to bring over enough floating voters to win decisively, there is the warning from Brexit about winning a major constitutional referendum on a broad principle, but without any agreed offer. That will not happen in Scotland, but there is still political pressure to postpone all sorts of big discussions to the other side of a future referendum. This limits debate now and has a detrimental effect on the choices and style of the Scotland that will emerge in the future.

A more open-minded debate is needed. One which goes past the constitution and even politics. It should raise the question of who are the change-makers and what qualities do we need to nurture and nourish in the present to facilitate this? Where are the interpreters and makers of Scotland’s future now? Some are already with us, doing the work and activities creating that change. They sit in numerous communities and organisations but are often found outside conventional settings. Instead, they are located in DIY organisations and the ‘third Scotland’ – of self-organising, self-determining activities – that emerged so powerfully in the Indyref campaign. This is more about an independence of mind, spirit and action – an autonomy of social practice – than constitutional change alone.

We see many examples of such action in the pages of this book. It can be found in the pioneering work of the Violence Reduction Unit (VRU) who contributed to challenging Glasgow’s, and then Scotland’s, culture of violence. Their initial strapline, ‘violence is preventable, not inevitable’, spoke to a refusal to accept the status quo and the fatalism that change was not possible. It then took on what were seen as immovable, taboo subjects like toxic masculinity, that sees men harm themselves, other men, women and children, as well as gang culture (Carnochan, 2015).

Such qualities can also be found in such initiatives as the Sistema Big Noise project. It set down roots in the Raploch estate in Stirling, using the power of music with young people to build confidence and social skills. It has proven so successful that it now exists in three of Scotland’s other cities: Glasgow, Aberdeen and Dundee.

They can be found equally in the life-affirming work of Galgael in Govan, in the heart of Glasgow. This has, over the past twenty years, provided space and sanctuary by using the ancient Viking skills of shipbuilding to reach out to a troubled generation of men and women, aiding them through reskilling. But, even more than that, it contributed to people finding a new purpose and confidence in life, while remaking the idea of community.

Another example is the range of community buy-outs that came after the land reform legislation passed by the first Scottish Parliament. The experience of the island of Eigg pre-devolution has been followed by a number of other cases such as the island of Gigha and estates in North Harris, Glencanisp and Drumrunie, and South Uist: all of which have proven successful and sustainable. Yet, the impetus gained from the initial legislation slowly petered out – a product of over-complicated process, a failure of national leadership to champion local energies and, from 2007, the relative lack of interest from the SNP in continuing the momentum of change (Hunter, 2012). Still, the buy-outs so far have shown what could be achieved by small groups of people coming together, not giving up and not listening to naysayers and pessimists saying that nothing would ever change.

Some of the same virtues can be identified in the steadfast commitment of community projects such as the Govanhill Baths in Glasgow. They took on their local council after it closed the baths in 2001. The community stayed for the long term, dug in and won. They were handed back ownership of the baths in 2019 to develop an ambitious community-led, and owned, health and well-being centre. The neighbourhood is the focus of a chapter – looking at the mix of vibrancy and problems it contains – which, because it sits in First Minister Nicola Sturgeon’s constituency, has attracted much right-wing media and commentary of a kind that is frequently not helpful and often not even bothered with accuracy.

If these currents of radical change are to be sustained, they need to find support, champions and resources. But its energy rapidly burns up and leaves one stranded, needing additional resources – an argument Fintan O’Toole explores at further length in his contribution to this book (O’Toole, 2014; see Walzer, 2015). They need a different kind of politics and a commitment to public services that can enter into genuine collaboration with places of innovation. This does not come easily and entails a fundamental rebalancing of how the state and public agencies act and relate to its citizens. It involves becoming a different kind of state. This was the implicit offer tantalising glimpsed in the latter stages of the 2014 independence referendum. But it is much harder to make real than the rhetoric suggests.

Maybe part of this promise in 2014 was a chimera that people wanted to believe. But it nonetheless captured the hopes and aspirations of a large part of Scotland who do not believe in old-fashioned state power no matter how benevolent it claims to be. Younger people in their twenties and thirties, in particular, feel let down and even abandoned by the state (which in most cases here means the British state) across the developed world. This requires a different approach to rebuilding trust and supporting people than simply hankering after the past.

There is a wide set of ideas and insights that can be drawn upon to chart our way to a different future. They point towards a path navigating away from the twin pillars of a supposedly enlightened, but often centralised and monolithic, state and of abandoning people to the mercy of an often-rigged market capitalism which lacks compassion or humanity in the harm it is inflicting – economically, socially and environmentally.

This path emphasises remaking relationships both in work and society. They are what gave rise to the Violence Reduction Unit. Such impact, the ideas of ‘radical help’, of self-organisation, remaking the state and the notion that the state has to have the courage and belief in people to let go in a manner which lifts people up, rather than abandoning them (Cottam, 2018; Goss, 2014). That, after all, was the vision inherent in books such as Lesley Riddoch’s Blossom. Blossom found an audience in the Indyref, but it has not yet translated from an attitude into an actual practice (Riddoch, 2013). All of this enjoys a rich resonance with older Scottish radical traditions that predate the rise of Labour state-ism in the Independent Labour Party (ILP), and others emphasising self-government as an organising set of principles for society – not just relying on a Parliament in Edinburgh.

Such thinking showcases the limitations of inherited, dominant political perspectives – from conventional social democracy to the bankruptcy of the neo-liberal project. It also underlines that no matter how ‘civic’, progressive and outgoing our nationalism is in intent, it does not, on its own, offer a sufficiently imaginative guide for the future. In the words of Fintan O’Toole, civic nationalism is like ‘a rocket fuel’, it can take you far in the initial stages, aiding the setting up of a new nation state. But its energy rapidly burns up and leaves you stranded, needing additional resources (O’Toole, 2014; see Walzer, 2015). That future terrain is one centred on self-determination, which is localist, feminist, empowering and green.

The Problem with Britain Beyond Brexit

One important dimension that has to be taken into account in charting Scotland’s future is the long-term direction of the British state, the crisis of that state and the exhaustion of the Tory and Labour versions of Britain, which have been exposed further, but not created, by Brexit (see Bogdanor, 2019).

The British state showed historic adaptability in legislating for a Scottish Parliament and a Welsh Assembly in 1997–98, preceded by affirmative referendums. It had the statecraft and intelligence to support the Northern Irish peace process leading to the path-breaking Good Friday Agreement (GFA) in 1998. This, of course, has been in danger of being undermined by Brexit and by the intransigence of hard-line Brexit advocates in the Tory Party.

But, long before Brexit, the UK had showed its long-term inability to reform and democratise. What we have seen in recent years has been the retrenchment of a unitary state nationalism, forgetting the inconvenient fact that the UK is not, in its character and make-up, a unitary state, but a union state made up of four nations.

In the years of devolution before Brexit, the UK saw Scotland, along with Wales and Northern Ireland, as boxes ticked, not as part of a larger story about an evolving, decentralising UK. There was no formalising of relationships between the devolved territories and the political centre. There was no codification or entrenchment of this supposed new settlement, and no remaking of Westminster and Whitehall. For all the talk over twenty years of the UK slowly moving to a federal or quasi-federal system, it has never amounted to anything substantive.

On the contrary, there has actually been retreat and denial. A remade UK had to ensure that its political core understood that it had to change and doing so – recognising that the way it did politics, and saw itself, was a problem. But, no real signs of this changing consciousness ever emerged under Labour, and certainly not under the Conservatives, with or without the Liberal Democrats. Instead, the United Kingdom has increasingly resembled a divided kingdom, with a unitary state mindset at the centre of what is, in fact, a union state. Then along came Brexit to add to these deep tensions.

Brexit is a product of a deeply rooted Euroscepticism in an English political imagination dominated by a reactionary form of nationalism. There are other Brexit sentiments, such as the historic Jeremy Corbyn-John McDonnell ‘Left Exit’ (Lexit) opposition to the EU. They have aligned themselves with this project and aided it, both in the 2016 referendum and afterwards. Brexit represents many failures, including that of pro-Europeans and progressives across the UK, but it is also a failure of alternative Englands to find voice and take on the forces of reaction and conservatism (Barnett, 2017). After all, there are numerous other English traditions and radicalisms which have at times found the strength and popular support to combine with Scottish, Welsh and Northern Irish sentiment to create majority coalitions for far-reaching change across these isles.

However, this alternative prospectus looks increasingly less likely in the future. This is not just because of the forces of backward English nationalism, which do not (for all their noise and disruption) speak for a majority in England and are probably still not even a majority in the Tories (although that may change). But because of the fragmentation and near-disappearance of any kind of homogeneous ‘British politics’ beyond Westminster. This makes it nigh impossible to conceive of a radical Labour Government coming to power under Corbyn, or a Corbynista successor, and implementing the kind of programme which it would like to do, and which deals with the structural inequities which disfigure the economy and society. It would either be blocked by establishment forces, fall through its own internal divisions, be scuppered by Brexit or otherwise dilute any radical plans, with the prospect of a reactionary backlash taking the UK further rightwards. All of this has implications for Scotland today and the future path it chooses to take.

Avoiding Scotland’s Groundhog Days

In these tumultuous times it is understandable that some people want to cling to the idea that political change is easy. That all that is required is the ‘will to power’, a leadership with the right line and not compromising in the face of adversity. That, after all, has been part of the appeal of Brexit, Corbyn, Trump and even some independence claims pre- and post-2014.

Yet, it is also true that too many people in Scotland are trapped by events of the recent past, and this stretches out beyond 2014, and even the devolution era. They look to the landscape and transformation of the country over the last 40 years, particularly by Thatcherism and what came after. The Thatcher Government presided over hugely unpopular economic and social policies, from painful deindustrialisation, to public spending cuts and privatisation and the hugely divisive poll tax. It is difficult, 40 years after this political revolution, to begin to gauge how fierce this attack felt at the time to so many people in Scotland and elsewhere. It is heightened now by the Tory lack of a mandate and a widening democratic deficit between Scotland and Westminster.

The economic and social changes which the Thatcher Government encouraged and aided – from the decline of steel, iron, mining, shipbuilding and away from traditional male dominated industries, along with the rise of new, service sector employment, would have happened without Thatcher and her ideology. It would have occurred, as it did in many other countries, in a much more managed and humane way, while protecting profitable parts of manufacturing. People would have felt less that it had been imposed upon them with destructive force.

This is less an argument about Thatcherism than it is about how the past is remembered and interpreted, the role of collective memories and how these impact on the present and future choices (Torrance, 2009; Stewart, 2009). Hence, a powerful part of Scotland’s political discourse after Thatcherism has been shaped by what has been called, in a very different context, the ‘children of the echo’ by Jarvis Cocker (Cocker, 2012). He was talking about the continued obsession with the 1960s and the mining of it with ever-diminishing returns. That decade was, he believes, a ‘Big Bang’ of imagination and creativity, which people have drawn from and referenced to, to the point that they have become plagiarists and copyists – Britpop being an obvious example of this, as Cocker concedes.

In Scotland, a large swathe of political debate on the centre-left and the left is seen through the prism of the 1980s and Thatcherism. It often adds the New Labour decade and Blairism onto the charge sheet, presenting them as an accommodation and even an extension of the dominance of the right. In this mindset, it is possible to frame most of the last 40 years of the UK in a caricatured way, which takes away any nuance or attempts at change. Such a view was expressed by the likes of former Communist and UCS work-in leader Jimmy Reid – who was otherwise capable of highly genuinely creative thinking – when he stated: ‘When New Labour came to power, we got a right-wing Conservative Government’ (quoted in Daily Telegraph, 11 August 2010).

This is a Scottish equivalent of the ‘children of the echo’ that poses a simplistic, linear and bleak picture of the past. 1979 is presented as ‘Year Zero’, and everything that happened after seen as negative, a loss and imposed on us. This is contrasted with the Scotland of today, and more often than not with pro-independence views, to assume and assert the character of radical views in the present. Neal Ascherson was tempted to do this in the last stages of the 2014 debate, when he argued for independence on the grounds that the UK had degraded itself to a ‘Serco state’, defined by privatisation and outsourcing, while overlooking the presence of such activities under the watch of devolution (Ascherson, 2014). This is a classic case of over-stating differences, one which masks the difficult choices we face in Scotland about public services, opposing privatisation and developing new models.

Scotland After Devolution

A Politics of Self-Government

We have to come to terms with the complex shifts that have happened in our country and society over recent decades, both under devolution and beyond, and locate them in the context of longer-term trends. These include the weakening of old collectivist norms, traditional forms of authority and power, and the rise of individualism – not all of the latter is reducible to right-wing reaction. For example, such a loosening up of society has aided Scotland to become more at ease with diversity, more multi-cultural, more pluralist and tolerant across a range of indicators – progress in LGBTQI+ rights being just one of the most striking. Connected to this is the decline of deference and hidebound forms of moral authority often associated with the Kirk, along with other types of social conservatism and the authoritarianism they often displayed. This has been an enormous gain for Scotland. Indeed, it has been such an all-encompassing change that it is often not even commented upon now. But it also raises serious dilemmas about what constitutes appropriate moral authority, and how we set agreed rules in a more diverse disputatious society.

Scotland has also experienced two ‘Great Disruptions’, seen in the independence referendum and then Brexit. The first a home-grown explosion of energy, and the second mostly imposed by English voters and motivations, with only a minority of voters in Scotland supporting it.

Some see the current climate of instability as one that calls for another Indyref as soon as possible. But this is a politics that puts process, the calling of a referendum and its timing centre-stage, rather than its substance. It chooses to ignore difficult questions. How it is possible to respect one majority while attempting to overturn it? How do we use referendums in a political culture which has not agreed a formal framework for them? That involves thinking about who calls them, how they are called, qualified and super majorities and how one mandate can supersede another. These concerns have all been fleshed out in public in the debate on a second EU referendum, or the ‘People’s Vote’, but they are just as germane to any future independence vote. They are as much about how to hold people with different desires in some sort of commonly accepted democratic space, while dividing on a major change, as they are about the mechanics and calculation of the process.

The increasingly self-governing Scotland that is now evident, and which all of us have played our part in bringing into being, faces many difficult choices and debates. But, in this it cannot be reduced to a politics centred simply on the date of any future independence vote, or upon constitutional politics. Rather, it is about the sum total of our actions: how we act, interact and respect one another, how we build each other up and our capacity to be a different kind of society from the present.

That Scotland involves a politics that is about much more than Holyrood and its 129 elected politicians, or the Scottish Government and its formal powers. It is about a Scotland where the Parliament and its politics are a catalyst for, and reflective of, further and wider change; where it plays its part in encouraging and supporting people to take more decisions regarding their lives.

Twenty years ago, there were two competing visions of the Parliament and the devolution on offer. The first was of the Parliament as an intrinsic idea – an institution as an end in itself and as a political voice and expression. In this account, the Parliament speaks for Scotland, whereas previously there was no voice. The second perspective was of the Parliament as an instrumental idea – of a means to an end, to develop a Scotland where power was shared and diffused through the community of the realm and held by all of us to aid our betterment.

Of course, the two overlapped in a number of respects, but they also point to different ideas about political authority, voice and ultimately purpose. One is more essentialist and uncontested in the way it poses these ideas; the other more qualified, contested, fluid and open to constantly evolving. The former draws more from 19th century notions of sovereignty, whereas the latter sits in the tradition of pooled and shared sovereignty. Given Scotland has a deepseated backstory of popular sovereignty (the ‘claim of right’) dating back 700 years, it is appropriate that we embrace it, renew it and apply it in our modern setting.

These two narratives illuminate the different paths Scotland has before it, one of which we have to choose. They have within them competing, contrasting futures: one where it is enough to have a self-governing Parliament and assertive Government; another where self-government amounts to the combined actions of millions of us as citizens, individuals and voters, practicing every day the democracy that Scotland could become and, in so doing, making us the kind of society where we make our collective future together. The first is about devolution and remaining within its paradigm or a very limited form of independence; the second is about transcending the constraints of devolution and involves a politics beyond the political classes. However, the constitutional question is shaped and handled, only one of these futures is worthy of the title ‘Scotland the Brave’.

References

Arrighi, G. (2009), The Long Twentieth Century: Money, Power and the Origins of Our Time, London: Verso Books.

Ascherson, N. (2014), ‘Scottish Independence: Why I’m Voting Yes’, Prospect, September 2014, available online at: www.prospectmagazine.co.uk/politics/independence-referendum-why-im-voting-yes

Barnett, A. (2017), The Lure of Greatness: England’s Brexit and Trump’s America, London: Unbound Books.

Barrow, S. and Small, M. (2016), Scotland 2021, Edinburgh: Ekklesia and Bella Caledonia.

Bogdanor, B. (2019), Beyond Brexit: Towards a British Constitution, London: I.B. Tauris.

Brown, G. and Alexander, D. (1999), New Scotland, New Britain, London: Smith Institute.

Brown, G. and Alexander, D. (2007), Stronger Together: The 21st Century Case for Britain and Europe, London: Fabian Society.

Carnochan, J. (2015), Conviction: Violence, Culture and a Shared Public Service Agenda, Glendaruel: Argyll Publishing.

Cocker, J. (2012), ‘The John Lennon Letters’, The Guardian, 10 October 2012, available online at: www.theguardian.com/books/2012/oct/10/john-lennon-letters-hunter-davies-review

Cottam, H. (2018), Radical Help: How We Can Remake the Relationships between Us and Revolutionise the Welfare State, London: Virago Press.

Curtice, J. (2019), ‘The Electorate and Elections’, in Hassan, G. (ed.), The Story of the Scottish Parliament: The First Two Decades Explained, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, forthcoming.

Drucker, H. (ed.) (1982), John P. Mackintosh on Scotland, London: Longman.

Goss, S. (2014), Open Tribe, London: Lawrence and Wishart.

Hassan, G. (2014a), Caledonian Dreaming: The Quest for a Different Scotland, Edinburgh: Luath Press.

Hassan, G. (2014b), Independence of the Scottish Mind: Elite Narratives, Public Spaces and the Making of a Modern Nation, London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Hassan, G., Gibb, E. and Howland, L. (eds.) (2005), Scotland 2020: Hopeful Stories for a Northern Nation, London: Demos.

Hunter, J. (2012), From the Low Tide of the Sea to the Highest Mountain Tops, Laxay: Islands Book Trust.

MacCormick, N. (1999), Questioning Sovereignty: Law, State and Nation in the European Commonwealth, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Mackenzie, W.J.M. (1978), Political Identity, Harmondsworth: Penguin.

McLeish, H. (2014), Rethinking Our Politics: The Political and Constitutional Future of Scotland and the UK, Edinburgh: Luath Press.

McLeish, H. (2016), Citizens United: Taking Back Control in Turbulent Times, Edinburgh: Luath Press.

Marryat, L. and Frank, J. (2019), ‘Factors associated with adverse childhood experiences in Scottish children: a prospective cohort study’, BMJPaediatrics Open, available online at: bmjpaedsopen.bmj.com/content/3/1/e000340

Maxwell, S. (2012), Arguing for Independence: Evidence, Risk and the Wicked Issues, Edinburgh: Luath Press.

Maxwell, S. (2013), The Case for Left Wing Nationalism: Essays and Articles, Edinburgh: Luath Press.

Mouffe, C. (2018), For a Left Populism, London: Verso Books.

O’Toole, F. (2014), ‘It is not that Scotland might become a new state but that it might become a new kind of state’, Sunday Herald, 7 September 2014, available online at: www.heraldscotland.com/opinion/13178696.it-is-not-that-scotland-might-become-a-new-state-but-that-it-might-become-a-new-kind-of-state/

Pryce, G. and Le Zhang, M. (2018), ‘Inequality in Scotland: despite Nordic aspirations, things are not improving’, The Conversation, 7 November 2018, available online at: theconversation.com/inequality-in-scotland-despite-nordic-aspirations-things-are-not-improving-105307

Riddoch, L. (2013), Blossom: What Scotland Needs to Flourish, Edinburgh: Luath Press.

Save the Children Fund (2013), Child Poverty in Scotland: The Facts, Edinburgh: Save the Children Fund.

Schlesinger, P. (2019), ‘What’s happening to the public sphere?’, paper to Media, Communication and Cultural Studies Association Annual Conference, University of Stirling, 9 January 2019.

Scottish Government (2017), ‘Poverty and Income Inequality in Scotland 2015–16’, Edinburgh: Scottish Government, available online at: www.gov.scot/publications/poverty-income-inequality-scotland-2015-16/pages/5/

Social Mobility and Child Poverty Commission/David Hume Institute (2015), Elitist Scotland?, London/Edinburgh: Social Mobility and Child Poverty Commission/David Hume Institute, available online at: assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/481851/Elitist_Scotland_Report.PDF

Stewart, D. (2009), The Path to Devolution and Change: A Political History of Scotland under Margaret Thatcher, London: I.B. Tauris.

Torrance, D. (2009), ‘We in Scotland’: Thatcherism in a Cold Climate, Edinburgh: Birlinn.

Walzer, M. (2015), The Paradox of Liberation: Secular Revolutions and Religious Counterrevolutions, New Haven & London: Yale University Press.

CHAPTER 1

How Scotland Can Keep Breathing

Neal Ascherson

SOME PEOPLE HAVE a dream; I have a nightmare. It is to find myself locked in a dark, airless nursery cupboard, somewhere in the south of England, with Boris Johnson, Jacob Rees-Mogg, Theresa May and Paul Dacre, former editor of the Daily Mail. In the darkness, I hear their snuffling and sniggering as they crawl towards me.

I have a nightmare, because that is the future after Brexit. Britain – and not just England who voted for it – will become a place the young want to leave. The lights are being dimmed; the windows closed tight, the shutters firmly snibbed over them. Somewhere out there in the fresh air, people with many nationalities and languages will be coming and going as usual; lively, crazy, imaginative futures will be constructed in France or Italy or Poland. Often enough those futures will collapse and need new designers. But here in soundproofed Brexit Britain – a bit poorer than before, a lot duller – we’ll scarcely hear the noises from outside.

Scottish culture will have to smash open airholes to keep breathing. But that’s something we already know how to do. Remember how John Bellany and Sandy Moffat went to Berlin and brought back the fire of German Expressionism to Scotland. Or, how Ricky Demarco went to Kraków and returned with Tadeusz Kantor’s theatre to inspire Scottish dramatists. Or how Lynda Myles went to France and Hungary and, aged 23, blew up the staid Edinburgh Film Festival with the avant-garde cinema culture she imported. Without European air, Scottish culture will begin to suffocate all over again.

Scotland still has a spare key to that locked cupboard in its pocket, a key tagged ‘independence’, if we dare to use it. But, Brexit itself is likely to happen now, whatever its form and political composition. We have had flirtation with the car crash of a ‘No Deal Brexit’ and the false hope of the supposedly less disastrous soft fudge Brexit. And yet, what these have shown is the hypocrisy in the soft options, and that the direction of travel is clear.

I used to think they’ll spend four years trying to get out, and the next four years trying to get back in. Now I’m not so sure. To use Nigel Farage language, the English majority will feel that they have won back independence from foreigners, and with a few grumbles, they’ll be content.

Europe, or more accurately the EU, is left in the lurch. George Soros is perfectly right about what needs to be done. Revive the idea of a two-speed Europe: a single currency integrated core, and a periphery of other nations preferring to stay with their own money.

Secondly, smash the German fogeyism of the European Central Bank – still in the lum-hat and stick-up collar age of banking. Show the bank how to help nations without forcing them to sit on the pavement and sell their frying pans and wedding dresses, like the Greeks.

This is easier said than done. So-called populism is the fault of European governments and EU policies, and the fanatical obstinacy of their neo-liberalism. To be dogmatic, the EU is coming apart basically because social democracy, or democratic socialism, betrayed its own people.

Two economic earthquakes – the collapse of Communist systems in 1989 and the banking disaster of 2007–08 – left winners but also more losers. People lost not only money and jobs but lost their feeling that their work mattered and was significant.

Socialists were expected to stand by those losers, their traditional constituency. But they had defected to collude with, and appease, the right. Blair veered to Thatcherism, the once great German Social Democrats destroyed themselves weakening the ‘social model’, Polish and Hungarian social democrats moved to forms of turbo-capitalism, and so on. So, they left a political vacuum. As a result, xenophobic, authoritarian and ultra-nationalist parties, but also welfare-ist, ones have rushed in to fill and colonise that vacuum.

Scotland’s Dilemmas

Scotland pre-empted that. The SNP turned out to offer a benign variant of populism in which many people who felt like losers – the 30-year collapse of traditional industries, the sense that the nation was becoming a collective loser in the union – could take refuge. But what now in these turbulent times? I see this as a twice-dangerous moment. It is true that the Scots – unlike the English – still have that silver spare key to escape through Ukania’s closed door. But will we use it?

The first danger is that Scots get increasingly put off EU membership. This is fatal. The truth is that an independent Scotland out with the EU would fall more rapidly into a ‘Scotshire’ dependency on London than the devolved Scotland we have now. The ‘power grab’ stushie with the Brexit Withdrawal Bill, which Scotland was never likely to win, shows how things will go. It is true there are reforms – heavy lifting jobs in Scotland needing state support and subsidy – which EU free competition rules would oppose. But much can be done in the interval between independence and admission.

By the way, pay no attention to vague threats of a veto, or to Brussels horror at the very notion of secession in one of its members. This is utter and transparent hypocrisy. No fewer than 20 out of the 27 EU’s members post-Brexit will owe their existence to a secession opposed by a larger state or empire, starting with the Netherlands in the dim and distant 16th century. I have a list somewhere which I could go through, but I will spare you.

The second danger is better defined as a bewildering possibility. I mean the possibility of a real and permanent division in the self-government and independence forces and opinion. A point to emphasise is that the independence issue is here to stay. In 2014, it became a sturdy, plausible option for Scotland’s future, it became part of the fabric, the furniture of who we are. Some wanted it, others did not. But it won’t go away now, although it may take different forms and leaderships.

The