Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: THP Ireland

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

The modern Irish planning system was introduced on 1 October 1964, when the Local Government (Planning and Development) Act, 1963 came into force 'to make provision, in the interests of the common good, for the proper planning and development of cities, towns and other areas'. Given the popular image of a post-Celtic-Tiger landscape haunted by ghost estates, ongoing efforts to address the notoriety of some public housing schemes and the fall-out from a planning corruption tribunal which spanned fifteen years, the time is ripe for reflection and analysis on the successes, innovations and failures of the Irish planning system. This book traces the evolution of land-use planning in Ireland from early settlements to the present day and discusses its role in meeting social, environmental and economic challenges and opportunities.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 400

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

Title

Acknowledgements

Introduction

1. From Monasteries to Wide and Convenient Streets

2. Civics and Rebellion

3. Planning and the Free State: A Seductive Occupation

4. Local Government (Planning and Development) Act,1963: The October Revolution

5. Garden Cities, Ballymun and Bungalow Bliss

6. Planning Drift

7. Boom and Bust

8. Picking up the Pieces

9. Places for People or Pension Funds?

Notes

Selected Bibliography

Copyright

Then prove we now with best endeavour,

What from our efforts yet may spring;

He justly is despised who never

Did thought to aid his labours bring.

For this is art’s true indication,

When skill is minister to thought;

When types that are the mind’s creation

The hand to perfect form has wrought.

Dr Bindon Blood Stoney, Preface to The Theory of Strains, Girders and Similar Structures (1873) as quoted in the Foreword to Dublin of the Future: The New Town Plan (1922)

Acknowledgements

For those interested in sustainable development, the built environment and where we live today and in the future, 2014 marks a series of important anniversaries. The modern Irish planning system was introduced on 1 October 1964, when the Local Government (Planning and Development) Act, 1963 came into force ‘to make provision, in the interests of the common good, for the proper planning and development of cities, towns and other areas’. The year 2014 also marks eighty years since the 1963 legislation’s predecessor, the Town and Regional Planning Act, 1934 and seventy years since a ‘National Planning Exhibition’ was held in an attempt to build support for the discipline and map Ireland’s post-war future. It also runs into the fortieth anniversary of the Irish Planning Institute – the Irish professional body for planners, which was founded in 1975.

An initial reaction when I told someone I was writing this history was ‘that’ll be a short book’. In fact the innovations, issues and compromises set out here show that there is a wide and uniquely Irish planning story to be told. The genesis of the book was a meeting with the publishers who saw that there was a worthwhile tale and I am honoured to have been given the opportunity to tell it. Thank you Ronan, Beth and colleagues.

This book would not have been possible without the patience and encouragement of my employers (the institute), and in particular the support of its immediate past presidents and vice-presidents, Joanna Kelly, Mary Crowley and Amy Hastings. Other past presidents of the institute – Patrick Shaffrey, Enda Conway, Joan Caffrey and in particular Fergal MacCabe and Philip Jones – patiently gave their guidance and time. Thanks also to my colleagues – Stephen Walsh and Ciarán O’Sullivan, who provided research support and always provided constructive criticism.

Many others require thanks for their help and encouragement, including Mary Hughes, Berna Grist, Antóin, Sandra, Gerard, Pat and most especially Ann and Áine.

I wish to thank Colum O’Riordan and all at the Irish Architectural Archive, Dr Mary Clark and Ellen Murphy at the Dublin City Library and Archive, the National Library of Ireland and Bill Hastings for their help and generosity in ensuring many of the images here could be reproduced to enhance and illustrate the story.

Introducing his 1941 Town Planning Report for Cork Manning Robertson said, ‘A town planner is much in the position of an editor compiling a volume’. Robertson’s sentiments equally apply to this planner and I am indebted to the people who agreed to speak to me for this book, provided me with documents and material or directed me to pertinent but perhaps obscure details. Of course while the final work is far richer because of these contributions, its contents, accuracy, opinions and omissions are entirely my responsibility.

Finally, my most special thanks go to Lorna, for everything.

Introduction

ORGANISING COMMON SENSE

Planning is chiefly concerned with places – regions, cities, towns, neighbourhoods and rural areas – and how they change and develop over time. In each of these places and at these different scales, the purpose of planning is to reconcile the competing needs of environmental protection, social justice and economic development in the interests of the common good.1 It affects the quality of life of everyone. Though the results of good planning may be silent, bad planning can be all too obvious.

Though organised place-making dates back further, modern town planning rose from the ashes of failed attempts to clear the slums that proliferated in Europe as a consequence of the phenomenal urban growth experienced at the time of the Industrial Revolution. Following the fall of the Ancient Roman Empire, it was not until the nineteenth century that urban populations reached such a size that they could not be managed solely through private interests. Cramped conditions, overcrowding, poor sanitation and lack of daylight access led to successive crises of public health throughout Ireland, Great Britain and continental Europe.

Despite these noble origins and the obvious social, environmental and economic value of taking an integrated, long-term view about the future of land and places, planning in twenty-first-century Ireland has a bad reputation.

Given the popular image of a post-‘Celtic Tiger’ landscape haunted by ghost estates, ongoing efforts to address the notoriety of some public housing schemes and the fallout from a planning corruption tribunal that spanned fifteen years, the time is ripe for reflection and analysis on the successes and failures of Irish planning. What can the past tell us about planning in Ireland or, more fundamentally, is there something in our makeup that makes planning unpopular, or indeed impossible?

Manning Robertson (1888–1945) was an Eton- and Oxford-educated Carlow native, who settled in Ireland in the mid-1920s. He was a town planner, architect, writer and the first chairman of the Irish branch of the UK’s Town Planning Institute, and his untimely death ‘robbed Irish planning of its most prominent practitioner’ who recognised that ‘Ireland’s planning problems were as much sociological as physical’.2

In 1941 Robertson wrote, ‘Town Planning has suffered a good deal from misapprehensions as to its aim and scope. One hears of it as an engine for demolishing masses of building with a view to replacing them with impossibly grandiose conceptions. In actual fact it aims at nothing more remarkable than seeing to it that a town develops on common sense lines. It enables common sense to be organised’.3 This echoes Robertson’s comments in a 1936 paper to the Architectural Association of Ireland where he said ‘town-planning has only one object in view – the application of common sense to the growth of a town and the development of the countryside’. Later Robertson observed ‘many people appear to believe that town planning means pulling down buildings: really it is the other way round: it aims rather at preventing buildings from being put up in the wrong place and then being pulled down again’.4

This is a history of planning in Ireland that looks at efforts to organise space and place in the country, from monasteries and plantations, and the common sense of Robertson, to today’s era of greater complexity.

A country’s approach to land-use planning cannot be separated from its culture. According to Professor Michael Bannon, who headed University College Dublin’s Department of Regional and Urban Planning from 1994 to 2002, ‘the aim, scope and nature of planning varies from country to country and each society must devise a planning system and foster a planning profession relevant to its peculiar requirements’.5 Planning theorist Nigel Taylor argues that the activity and effects of planning should not be interpreted as if planning was an autonomous activity, operating separately from the rest of society, instead it is necessary to ‘situate’ planning activity within its wider ‘political economic context’.6

Rather than just an account of the Irish planning system put in place by legislation, this book seeks to ‘situate’ planning and tell the wider story of how, when and why planning in Ireland emerged and why it operates the way it does. This publication traces the evolution of land-use planning in Ireland and the social, environmental and economic problems and opportunities that gave rise to it. Its structure is largely chronological. It deliberately does not chronicle every interpretation of Irish planning legislation or regulation. This is because it is essential to drill deeper and take stock of the wider rationale and principles of Irish planning, not just the legal, technical and administrative aspects which have spawned dozens of legal texts, fact books, manuals and thousands of legal cases.

Planning’s role in balancing environmental considerations, scarce resources and constitutional property rights, with the underlying principle of the common good is explored through a study of the Irish experience of democratic accountability, new towns, one-off rural housing and urban sprawl. It concludes by assessing how well planning’s cross cutting consideration for environmental, social and economic issues prepares Ireland for the challenges of climate change and developing the sustainable communities of the future.

A STREAK OF ANARCHY

In 1960 Patrick Lynch – chairman of Aer Lingus and lecturer in economics at University College Dublin – argued that ‘planning is unpopular in Ireland, sometimes even among those who might be expected most advantageously to employ it. Such are the unreasoning attitudes towards it that the term is often used as an emotive one, suggestive of voices signalling the road to serfdom, or speaking the foreign accent of social engineers’.7

For planner Brendan McGrath ‘planning has a precarious status in contemporary society’ challenged by a lack of consensus and discourse on the ‘common good’ and a persistent belief that models from elsewhere cannot apply to Ireland.8 Theories about Irish attitudes to planning, mainly tied up with religion, colonialism and land, abound.

It has been suggested that in a country which derived its independence from a land-based revolution, and where land interests remain strong, concepts of land management and the redistribution of the windfalls from profits in land are often hard to swallow.9 Planner and architect Fergal MacCabe argues that ‘the famine of the mid-nineteenth century and the subsequent land wars and (until recently) an essentially rural society, produced a deep respect for the unfettered ownership of land and a distrust of the compromises of urban living which informs public attitudes to planning to this day’.10 Bannon argues that the blood and rupture of the War of Independence, Civil War and partition did not allow for long-term national planning and that in both the Free State (prior to independence) and the partitioned Northern Ireland, power rested with rural politicians who had little interest in solving urban issues.11 The Irish Rural Dwellers Association (IRDA) has criticised ‘the extraordinary amount of power bestowed on individual planners by legislation to play God with the rights of Irish citizens wanting to build a home in the country’.12

Historian Erika Hanna notes the remarks of a writer from Northern Ireland who saw a ‘streak of anarchy’ in the Republic regarding planning laws, characterised by ‘a common attitude towards law and authority … a combination of a disregard for the rules by some, and a resigned acceptance by the others that the rules will not be enforced’.13

Frances Ruane, director of the Economic and Social Research Institute in Paul Sweeney’s optimistically-titled 2008 book Ireland’s Economic Success: Reasons and Lessons suggests ‘the biggest weakness in our system at this point is our attitude to space and physical planning … the Irish are enormously good at the economic and social but we don’t manage the environmental, by which I mean the spatial, very well’.14 Ruane attributes this to a ‘post colonial’ legacy of ‘I have my house and my land and I should be able to do whatever I want with them’ attitudes combined with low population density and a history of population decline. According to Ruane this means we ‘effectively have built a mind-set that does not handle space very well and that it is not surprising that we do not embrace planning principles’ in contrast to other more dense and urban European countries.15

Reflecting as he retired from an eleven-year period as chairperson of An Bord Pleanála which covered the recent boom and bust, John O’Connor raised the theory that there is an element of chaos in the Irish character that makes us sceptical of regulation or planning. ‘Rules are there to be broken if you can get away with it. This may account for some of our very serious failings over the past decade. It may also explain why the Irish body politic has been reluctant to embrace fully real spatial or land-use planning’ O’Connor said, explaining that unlike other countries, even when statutory planning documents are adopted ‘a laissez-faire approach often prevails and many vested interests – landowners and developers – see plans as something that can be got round or changed’.16

Environmental consultant Peter Sweetman is one of the most vocal critics of Ireland’s approach to development and environmental issues and is a regular contributor at An Bord Pleanála oral hearings. According to Sweetman ‘the Irish have a phobia against planning – not just the Planning and Development Act – we don’t plan anything. We have muddled along with water, we’ve muddled along with sewage, we’ve muddled along relevant to roads, we built some roads that were necessary and some that were totally unnecessary’. When asked if there has been any improvement in Irish planning he argues ‘it’s a fundamental point of Irish projects; they tell us what they are going to do rather than ask you – despite the EU-imposed need for Environmental Impact Assessments. So we still don’t know where we are – look at the history of the National Children’s Hospital. The whole aquaculture system is off the wall – bananas. Then we have raw sewage discharging into places like Newport’.17

An official apathy to planning and planners is repeatedly evident at the highest level. At the height of the ‘Celtic Tiger’ (the now ubiquitous phrase first used by Kevin Gardiner in a report for Morgan Stanley in 1994 that forecast more than a decade of surging economic growth), then Environment Minister Dick Roche complained of the attitude of planners, urging them ‘to show courtesy and consideration’ in dealing with the public, and to make themselves available to people building new homes. Roche continued: ‘You can walk into St Luke’s [Bertie Ahern’s constituency office] and have a meeting with the Taoiseach, or you can go to his various constituency clinics … I find it mystifying that planning officials, important as they are, don’t have anything like the same level of availability’, concluding that in any case ‘Planning is not rocket science, it is not even an exact science’.18

LANGUAGE AND ETYMOLOGY

In one of the first cornerstone textbooks on planning, 1952’s Principles and Practice of Townand Country Planning, Lewis Keeble wrote ‘planning is a subject in which there is room for endless debate and this creates an extremely difficult problem’.19 As Bannon writes, ‘planning might usefully be viewed as a cabinet, rather than a departmental issue’.20 The term ‘town planning’ can be traced to the Australian architect John Sulman who used the phrase in a paper titled The Laying-Out of Towns in 1890. It has evolved over the years and has been variously described as town and country planning, town and regional planning, physical planning, spatial planning and simply, planning.

When setting the scope of this publication I drew from Manning Robertson, who discussed what he considered might properly be called ‘town planning items’. Clearly planning embraces housing but equally housing development was carried out before town planning. Similarly roads and open spaces existed before town planning legislation but how people travel between work, home and amenities is inseparable from good planning.

Authored by Berna Grist, the 1983 report Twenty Years of Planning: a Review of theSystem since 1963 began by discussing the nature of the planning ‘system’, emphasising that while things like economic policy goal setting, service delivery and building regulations, along with spatial planning might all be considered as part of a national ‘planning’ system, the physical, or spatial, planning system can be separated from these interrelated systems but this rarely occurs in the public mind. Thus sometimes problems are attributed to ‘planning’ which can undermine public confidence in professional planners when in reality they can often be the responsibility of other, related disciplines.

Members of the planning profession are graduates of professionally-accredited third-level colleges or universities. Their primary function is to plan: to envision sustainable futures for places and to work in partnership with others in bringing about change in meaningful and effective ways.

Planners work in the public, private and voluntary sectors in a variety of roles. With a wide range of skills, they advise decision-makers (such as national and locally elected democratic bodies), communities, investors, interest groups, business people and the public at large on issues to do with the spatial development, growth, management and conservation of regions, cities, towns, villages, neighbourhoods, local areas and parcels of land everywhere, though others offer planning services while not being trained planners or members of any professional planning institute.

The making, reviewing and varying of the plan is a function reserved for the elected members (i.e. councillors) of the planning authority. It is their duty to adopt the plan with the technical help of their officials (the manager/chief executive, planners, engineers etc.), and following extensive public consultation.

All decisions to grant or refuse planning permission are taken by the relevant planning authority and then, if there is an appeal of the decision, by An Bord Pleanála. After reviewing and integrating information from across local authority departments and considering the results of site visit guidelines, plans and policies, the planner recommends a decision and a written report outlining the reasons is presented to the manager/chief executive of the relevant local authority who reviews it and decides whether permission should be granted or refused. The final decision at this stage of the planning permission process lies with the manager of the local authority. The decision-making process is not an arbitrary system; it follows a step-by-step procedure. It is designed to be transparent, to facilitate agencies and to present the public with the opportunity to voice their opinions and become involved in the process.

Fundamentally, there may be an issue with the term ‘planner’ itself, which suggests a degree of authoritarianism, certainty and control. When planning for an area it might be assumed that planners have control over a range of factors, including health, transport, etc. that will in fact only be delivered to the timetable of the agency or business that supplies them. In Europe other words are used which may more closely capture the nature of the discipline and its role, such as the French term ‘urbaniste’ which implies specialism in the study of our built environment, land use, place-making and the interactions around it.

Clinch, Convery and Walsh quote approvingly George Bernard Shaw’s assertion that a profession is a ‘conspiracy against the laity’ and suggest that professions underline this unconscious conspiracy through jargon and their central idea or ‘idée fixe’ to which they retreat when seeking solutions so ‘the profession predetermines the decision’.21 This risks isolating a profession and discipline from the public and increasing distrust and apathy. This is particularly unforgivable for a field with the common good at its core. In this book jargon is either avoided where possible or clearly explained if unavoidable.

The legal rationale for all planning decisions in Ireland is ‘proper planning and sustainable development’ with sustainable development accepted as encompassing social, economic, cultural and environmental concerns. This confirms that planning can be a broad church and, as shown above, it is inseparable from the wider political and cultural context.

DEEP ROOTS

Despite these perspectives on antipathy towards planning in Ireland, it has deep roots and has seen many innovations. The Dublin Wide Streets Commissioners, established in 1757, was one of the earliest town planning authorities in Europe and the independent third-party planning appeals system operated by An Bord Pleanála (The Planning Board) is still unique in Europe. The 1934 Irish planning legislation was considered far better than its UK equivalent. Before and after independence Ireland was visited by leading figures in Anglo-American planning with the country ‘an essential stopping-off point for many planning advocates, apostles and gurus’.22 The ‘First International Conference on Town Planning’ was held in London in 1910 and by the following year Ireland was described as ‘a most interesting field for the student of town development’.23

Writing on post-colonial Dublin, academic Andrew Kincaid notes that few histories of Ireland mention that leading international figures in town planning were involved in planning in Ireland. While ‘historians, politicians, and writers’ grappled with issues of social, cultural and economic change at various stages of Ireland’s history ‘architects and planners both reflected those debates and forged their own answers to them’.24 Kincaid also questions why the wider body of literature on planning history does not examine Ireland in any great depth or assess why such eminent thinkers wished to do work here.25 This volume attempts to put this right. Post-partition this work chiefly considers planning in the Republic of Ireland, along with recent cross-border initiatives.

It is essential to discuss the history of planning outside of Dublin as many initiatives came from outside the capital. For example, Waterford had Wide Streets Commissioners and the county saw a failed attempt at a new city, as well as one of Europe’s finest examples of a model village in Portlaw. The midlands feature some of the best practice housing schemes of the 1940s in the work of Frank Gibney, while Cork and Limerick led the way in regional planning in Ireland.

PLANNING FOR GROWTH

Perhaps to its detriment, planning has always been inextricably linked with economic development in Ireland. For example, Bartley describes the introduction of the Local Government (Planning and Development) Act, 1963 as part of the desire to create a modernised planning system which was seen as a prerequisite for Irish economic growth and prosperity. Bartley states that while the 1963 legislation explicitly linked planning with development, the former ‘was viewed as the processes of innovation and activities designed to increase resources or wealth’ while the latter ‘was seen as the means of managing the process through the allocation and use of resources’.26 Introducing the 1963 legislation to the Dáil, Minister for Local Government Neil Blaney gave a detailed statement of its aims and content, including that ‘property values must be conserved and where possible enhanced’.27

Despite this link, it has not necessarily contributed as much as was anticipated. In his discussion of Ireland’s economic growth in the 1960s, historian Diarmaid Ferriter suggests that there was a notable failure to copperfasten the country’s economic development through planning. Ferriter traces this to wider disinterest in planning, noting that President Douglas Hyde was advised not to attend the 1942 National Planning Exhibition as it was felt planning was not developed in Ireland and attendance ‘might eventually, bring the president into ridicule’.28 The 1963 Act expected local authorities to become proactive development corporations acquiring and developing land commercially. This did not come to pass. Similarly during the ‘Celtic Tiger’, commentators suggested that Ireland’s boom was despite, not because, of planning. Perhaps this narrow focus on the economics of planning without considering the wider context explains some of the hostility and why broad public support for the discipline and its aims has been hard to maintain.

According to a 1983 study of planning in Ireland, the planning process here never attained the public acceptability its counterparts in Britain or Europe enjoyed, characterised by the 1963 Act which was legislature-led with little reference to public attitudes and with public opinion courted only after its enactment.29

CONCLUSION

Writing in 2003 Bartley and Treadwell-Shine identified three phases in Irish public policy since independence and associated trends in planning. The first, from 1922 to 1960, was pre-industrial with a focus on economic isolationism and self-sufficiency with a minimal consideration of planning limited to housing. The second phase, from 1960 to 1986, was one of urbanisation, industrialisation and seeking inward investment with authoritarian, centrally controlled planning. The third phase from 1986 was post-industrial with more entrepreneurial and flexible planning.30 Post-‘Celtic Tiger’ Ireland has entered a recovery phase, with planning asked to assist economic growth while addressing the mistakes of the recent past. This might be the most challenging phase for the discipline so far, though as we will see, planning has a deep well of Irish experience and achievement to draw from that extends well before the founding of the Free State.

1

From Monasteries to Wide and Convenient Streets

EARLY IRELAND

In fifth-century Ireland there were no towns or cities, forests and bogs were extensive and the ‘numerous un-drained lake and river valleys and lowlands created many watery wildernesses in which the travelling stranger would almost literally be at sea’.1 There was the ráth, an individual settlement usually inhabited by a farmer with dwelling space enough for his family and animals, and the bigger dún, a dwelling place large enough for the king as well as his noblemen.

With the arrival of Christianity in Ireland from AD 431 came the establishment of monastic settlements through the middle of the island and by the sixth century monasteries were evident in all areas of Ireland. These early-Christian sites had similar layouts, in particular a regular curvilinear plan form, which has been interpreted as an early, widely adopted, model of spatial planning. Where urban centres grew up around ecclesiastical foundations, the lines of the original curved enclosures were often still visible in the property boundaries and street-plan of the modern town or village, such as in Kells, County Meath.2

Though the monastic settlements were nucleated settlements, it was the Vikings who created Ireland’s first true towns. In the ninth-century Viking settlements at Dublin, Waterford, Wexford, Youghal, Cork, Limerick and Galway developed. The Vikings permanently reoriented Ireland’s economic and cultural centre from the midlands to the east coast. Excavations suggest that building styles and plot layouts were rigidly regulated in Viking Dublin in perhaps Ireland’s earliest development control system.3 After the Anglo-Norman invasion beginning in 1169, stone castles and walls were constructed, while these Viking plot boundaries were often preserved into the eighteenth century. The Normans introduced the town charter that conferred urban autonomy and confirmed the importance of the marketplace and town wall.

THE PLANTATIONS

Plantations began in Munster and western Leinster at the end of the sixteenth century and they had a strong urban element. Some 400 new settlements were established by plantation grantees during the seventeenth century. The success of Richard Boyle in Cork had confirmed the role of towns in plantations, laying out Bandon with a grid-iron layout, with a marketplace at its centre. In 1609 Sir Arthur Chichester, the lord deputy of Ireland from 1605 to 1616, sought a survey of Ulster, meaning the plantation was preceded by what might be considered Ireland’s first regional plan. Indeed ‘the methods used were very much the same that would be adopted in similar circumstances today’ as they appointed a committee and commissioned a survey and report.4 ‘The planners took the view that the lands in Ulster, although containing large areas of forest and bog, were capable of supporting a greatly increased population if the resources of the province were properly exploited, and if the population became settled in towns and villages.’5

This resulted in the planning of twenty-five new plantation towns, which were to act as centres of civility and stability. The plantation commissioners were to decide how many houses should initially be erected in each town, laying out their sites, and assigning land for further building.

At Londonderry a grid was favoured, in keeping with the Enlightenment support for rational, orderly town plans. Descartes observed in 1637: ‘These ancient cities that were once merely straggling villages and have become in the course of time great cities are commonly quite poorly laid out, compared to those well-ordered towns that an engineer lays out on a vacant plan as it suits his fancy. And although, upon considering one by one the buildings in the former class of towns, one finds as much art or more than one finds in the buildings of the latter class of towns, still, upon seeing how the buildings are arranged – here a large one, there a small one – and how they make the streets crooked and uneven, one will say that it is chance more than the will of some men using their reason has arranged them thus.’

The Irish plantations, and in particular the plantation of Ulster, saw the establishment of formal new towns designed around a central square or ‘diamond’ in a style very different to Ireland’s medieval towns. Timahoe, in County Kildare, is a good example of where the seventeenth-century triangular green or ‘diamond’ is preserved.

Part of the legacy of the plantations was a new approach to laying out towns and in Ulster the network of new towns, linked by new roads, was to contribute to its economic strength. It has been noted that this imposed background might have set a persistent apathy to planning amongst some.6

WIDE STREETS COMMISSIONERS

As Dublin city developed, streets became crowded. In 1780 Arthur Young described walking the city as ‘a most uneasy and disgusting exercise’.7 Despite this ‘certain guiding principles of planning did apply’ to Dublin’s development, post-1660.8 Part of this saw the city permitting development on greens and commons which historian Colm Lennon somewhat tartly describes as ‘an innovative attitude to urban planning on the part of the municipality’.9 St Stephen’s Green was the medieval commons most radically affected. In 1663 the civic assembly approved leasing parts of the green and the following year, ‘the process of letting was under way, plots being divided among the aspirant developers by lot. As well as determining the size of the lots (sixty feet as frontage and from eighty feet to 352 feet in depth) and the rental (from 1d per square foot for the north side to a ½d for the south), the city council stipulated the dimensions and materials of houses that lessees were to build’.

The Commissioners for Making Wide and Convenient Streets and Passages, or as they came to be known, the Wide Streets Commissioners, were responsible for massive changes to Dublin’s city centre during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Originally established to alleviate a traffic bottleneck at Essex Bridge, the commissioners eventually shaped large portions of Dublin to their own tastes by widening narrow streets, creating new ones and enhancing their own properties.10

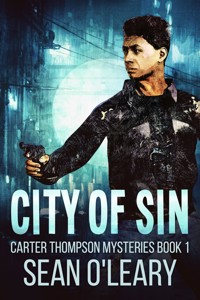

Map showing the Dublin Wide Streets Commissioners first undertaking, the making of a wide and convenient way from Essex Bridge to Dublin Castle (present-day Parliament Street). (Courtesy of Dublin City Library & Archive)

In 1755 a wider, reconstructed Essex Bridge crossing the Liffey at Capel Street was opened. The designer of the bridge, George Semple, published a map in 1757 which proposed a street leading from the bridge to a square in front of Dublin Castle and a bill setting up commissioners to oversee the work received royal assent. The 1757 Act of Parliament to make ‘a wide and convenient way from Essex Bridge to the Castle of Dublin’ (present-day Parliament Street) was the first of a series of street improvements. The commissioners controlled the planning of Dublin until 1851.

The commissioners set about their work quickly. In May 1758 notices appeared in the Dublin Journal, Dublin Gazette and the Universal Advertiser, requesting landowners and residents affected by the new street to voice their concerns to the clerk of the commissioners, Mr Howard.11 Success has many parents and architectural historian Maurice Craig recounts that both Semple and George Edmond Howard, the bridge’s contractor, both claimed credit for the idea of a new street, though in fact the first suggestion can be traced to 1751.12

MacCabe describes the Dublin Wide Streets Commissioners as ‘Europe’s first official Town Planning Authority’.13 Gough has persuasively argued that the Wide Streets Commissioners were ‘an early modern planning authority’ with ‘an excellent grasp of civic design and town planning matters’. The Age of Enlightenment was rippling across planning in Europe and Ireland was to the fore. Following the Lisbon earthquake of 1755, work had begun on re-planning that city with plans also being made for the New Town in Edinburgh.

The 1757 and subsequent acts empowered the commissioners to improve the city by widening streets where they saw necessary. Having opened up Parliament Street in 1762, the commissioners widened Dame Street, then Sackville Street. The commissioners included John Beresford, Revenue Commissioner, Luke Gardiner (grandson of the earlier Luke who was owner of Sackville Street, Dorset Street, Parnell Street and Square (then Rutland Street and Square) and Mountjoy Square), Frederick Trench and Samuel Hayes who studied developments in London and Europe evolving them into a unique approach.

The commissioners had the authority to acquire property by compulsory purchase, demolish it, lay down new streets and set lots along them that were released to builders for development. They had the authority to determine and regulate the façades of buildings erected along its new streets, decide on the heights of buildings, the number of houses in a terrace, the materials to be employed and the number and siting of windows. The commissioners could order rebuilding where necessary and actively resisted encroachments on the building line.

The commissioners’ compulsory purchase powers saw valuation juries recommend valuations to the commissioners. Gough describes the process as ‘an attorney’s paradise’ somewhat similar to today, given that the process could take up to thirteen months.14 Premises were sometimes acquired that were not required for street widening but which were incompatible with the commissioners’ vision for the new street.

Leases for plots along the newly-widened streets were regularly publicly auctioned and construction was on the architectural elevations stipulated by the commissioners, with some uses (such as ‘offensive or noisy trades’) or projecting signs often not permitted. The commissioners took enforcement proceedings against offending buildings, demanding that a carpenter on Dame street alter his windows in line with the plan laid down for example, while in 1801 the Sun Insurance Company was not permitted to widen their doors to admit their fire engines. 15 As funding became an issue, controls were relaxed.

In 1765 Wide Streets Commissioners were created in Cork and in 1784 in Waterford. Funded partially by court fines, the Waterford Commissioners were appointed to improve the city as ‘the streets, lanes and passages of the city of Waterford and the suburbs thereof are too narrow, by means whereof the health of the inhabitants is greatly injured and the trade of the said city is greatly obstructed’.

In Waterford the mayor or sheriffs were given powers to remove all encroachments and nuisances, including stairs, window shutters and sheds, which impeded the streets and lanes of the city and the commissioners laid out the Mall. The mayor also had the power to direct owners to move signs, ‘spouts and gutters’ and certain activities were prohibited close to the thosel.

In Cork, their primary job was to widen the medieval laneways and thereby eradicate some of the health problems stemming from them. Cork’s commissioners had powers to create public water fountains to address the undesirable situation where there was only one public fountain in the city. There are no early records of the Cork Wide Streets Commissioners’ proceedings (It is likely that these were destroyed in the County and City Courthouse fire of 1891 and the burning of the City Hall in 1921) but the commissioners have been credited with the laying out of Great George’s Street (now Washington Street), South Terrace, Dunbar Street and the widening of others.16 Historian Antóin O’Callaghan notes the similarities between the situation in Dublin and Cork at the time with expansion eastwards in both cities leading to the creation of a new city centre and with a new main street.17 O’Callaghan notes that in Cork the Corporation and commissioners were largely the same people with a significant Freemason influence, describing the close interaction of commissioners, Masonic lodges and Corporation at the opening of the first St Patrick’s Bridge in 1789.18 In Cork the commissioners seem to have had a philanthropic role, petitioning the Lord Lieutenant in 1822 to release funds for a quay between St Patrick’s Bridge and North Gate Bridge for a scheme recommended by the committee for the relief of the poor to provide employment.19 The relief committee also provided loans to the Cork Wide Streets Commissioners for various public works, including the extension of Penrose’s Quay by around 700 feet.

There was a wide interest in planning in the period. In 1789 the Cork Society of Arts and Sciences, an organisation that occasionally proposed new streets, received a map (‘A survey of the city and suburbs of Cork’) which they had commissioned for town planning purposes. It included a list of references to intended improvements, including the opening of new streets and broadening streets.20

Much of the development of Limerick after 1750 is associated with Edmund Sexton Pery, a parliamentarian and a businessman who pioneered the city’s Georgian architecture, laying out Newtown Pery. In these projects, his influence in parliament was a major factor as it enabled him to obtain large sums of public money for the improvement of Limerick and therefore of his own property around the city. Blocks were leased and built upon by individuals over a long period of time and the area did not assume its final shape until the 1820s and 1830s, when the last streets, such as Hartstonge Street, Catherine Place and The Crescent, were built.21

The Dublin Wide Streets Commissioners themselves were a group of upper-class landowners who were typically members of parliament. Many of the early commissioners were patrons of fine architects and were amateur architects. The initial twenty-one commissioners included Arthur Hill, commissioner of revenue and later chancellor of the exchequer; Thomas Adderley of the Barrack Board, Philip Tisdall, later attorney general and John Ponsonby, speaker of the House of Commons and the Lord Mayor of the day.22 Many of the initial commissioners ‘believed in minimal interference from England’23 though they had support from the Dublin Castle executive (‘as it was in their interest to have a decent approach to its own place of business’) and the Chief Secretary William Eden (with one of the commissioners ensuring Eden Quay was named for the Chief Secretary at his request for a street named after him).24

Gough writes that ‘unlike a modern planning authority the commissioners had no massive development plan but they did have a plan and vision of how they wanted the city to develop’. This was co-ordinated by ‘what can only be described as planning policy meetings’.25 The commissioners looked overseas to cities such as London, Paris and Philadelphia for inspiration. Gough traces a French influence in Dublin’s planning in the late eighteenth century, including its quays and building layouts.26

Commissioners included early proponents of new towns in Ireland, including Thomas Adderley, Anthony Foster, William Burton Conyngham and Beresford. Adderley and Foster had laid out their own planned weaving villages at Innishannon in Cork and Collon in Louth respectively while Conyngham planned a new island settlement off Donegal called Rutland with streets named after fellow commissioners.

Beresford, along with some other commissioners, sponsored the proposed development of a new town called New Geneva, designed by James Gandon, in Waterford. This was to accommodate a colony of disaffected Genevese exiles (including many intellectuals, craftsmen and watchmakers) after a failed rebellion against the French and Swiss Alliance, on 11,000 acres near Passage East. An invitation to immigrate to England following the rebellion had come from George III but the Genevese themselves, fearing the jealousy of English watchmakers, pressed that their colony should be in Ireland, not England. The Duke of Leinster offered them 2,000 acres for their colony near Athy and accommodation for 100 in Leinster Lodge until their houses were built, but the Waterford site and a £50,000 grant for the building of the town was arranged by the Viceroy Lord Temple with a view to the Protestant settlers calming nationalist feelings in the region, though the Genevese saw their role differently.27 The colony was initially to have fifty houses, a bakery, inn, tannery and paper factory. There were plans for a big square dominated by a university. An Irish enthusiast, Mr Cuffe, laid the foundation stone for the projected city in 1784 but six weeks later the plan was abandoned. The Genevans attributed its failure to a change of Viceroy with the Duke of Rutland less enthusiastic than his predecessor. It was then proposed to colonise the site with American loyalists following the War of Independence,28 but the site became the Geneva Barracks and prison and was featured in the ballad The Croppy Boy. If completed the project would have radically altered the shape of the south of the country.29

As the members of the commissioners changed through the decades, so did the legislative power given to them. The initial act enabling the commissioners to create Parliament Street was expanded in 1759 to allow the commissioners to examine the possibility of developing more than one street. Their finances were boosted with another act in 1782, enabling them to receive a sum of one shilling per ton of coal imported into the country.30 In August 1792 the jurisdiction of the commissioners was expanded to half a mile beyond the North and South Circular Roads, thereby increasing the amount of development the commissioners could implement. Additionally, it was advertised that anyone who wished to create a new street within the jurisdiction of the commissioners must submit plans to its retained surveyor Thomas Sherrard’s private practice office at 60 Capel Street.31

Ink and wash drawing (after James Gandon) of the proposed layout of New Geneva, a new town near Passage East intended for a colony of disaffected Genevese exiles in 1784. (Courtesy of the Irish Architectural Archive)

Examples of the Commissioners ‘planning authority’ role abound. Elevations for No.1 Merrion Square (which was to be the childhood home of Oscar Wilde) showing an extended porch were submitted to the Wide Streets Commissioners in July 1836. They rejected the proposal, ruling that the extension would constitute an encroachment on the pavement. The householder applied for permission again in 1837, pointing out that his neighbours had no objections and approval was granted.

In 1828 property speculator Benjamin Norwood built a wall along a section of Lower Baggott Street to screen stables he had erected, but local residents objected to the commissioners, who ordered Norwood to demolish the stables. Norwood demanded compensation from the commission if he built four houses on the site of the stables in Lower Baggot Street and submitted an elevation in 1832. The Wide Streets Commissioners approved the elevation but declined to vote a subvention as Norwood requested. In the absence of a financial commitment from the commissioners he did not proceed with his plans and in 1834 they successfully brought a court action against him and forced him to demolish the stables.

A development on Cavendish Row was approved by the Wide Streets Commissioners in 1787 that featured an unusual style. A note by the architect explains ‘the style of building proposed here has long been in use on the Continent, and found uncommonly convenient in procuring bed chambers contiguous to shops of the apartments of persons in trade, unconnected with the upper floors’. This refers to the provision of apartments at mezzanine level over ground floor shops with entirely unconnected residential accommodation overhead.

Elevation for No. 1 Merrion Square (which was to become the childhood home of Oscar Wilde) submitted to the Wide Streets Commissioners seeking permission for external alterations. (Courtesy of Dublin City Library & Archive)

In the late eighteenth century, maps of Dublin showed several streets radiating from an elliptical ‘Royal Circus’ in the north of the city. This was a ‘rare and remarkable instance of city plans, indicating some features of street planning not actually in existence’ as Luke Gardiner’s proposed plaza did not come to fruition.32

In the 1790s Henry Ottiwell privately (rather than at auction) acquired a large parcel of land from the commissioners. It was suggested that Ottiwell had a secret partner in the transaction, the son of John Beresford who was both a Revenue Commissioner and a Wide Streets Commissioner. This was investigated and it was suggested that a private sale might secure a better bargain for the public compared to an auction that might be manipulated by a cartel of builders. Ottiwell refused to name his partner and in 1795 a House of Commons committee investigating the deal committed him to prison for a few weeks and concluded that the commissioners had exceeded their powers. In telling Ottiwell’s story Gough calls him a ‘classic property speculator’ who bought the land over the market price and ‘inflated the value by lending money to his tenants, who thus could afford the higher prices’. Ottiwell was exposed when the 1798 rebellion and the 1800 Act of Union hit property prices and he was left with expensive land and outstanding loans that his tenants could not afford to repay. This also exposed the commissioners, as Ottiwell had rents arrears of £21,770 17s outstanding to them.33

In 1808 the Nelson Pillar committee wrote to the commissioners seeking permission to erect the memorial at the intersection of Henry Street and Sackville Street. In what Gough describes as a show of independence, the commissioners refused permission, citing public inconvenience. The committee subsequently met with the commissioners and when they agreed to reduce the width of the pillar and the shape of its surrounding railing consent was granted.34

Gough suggests that the commissioners understood the concepts of betterment – that is that public works can lead to an increase in property values for the private individual, and planning blight, meaning the reduction of economic activity or property values in an area resulting from expected or possible future development or restrictions. To avoid paying for the rising costs of betterment the commissioners had a policy of purchasing all the land they required for a project at the same time rather than buying on a piecemeal basis.35

Despite the majority of the commissioners being members of parliament, they did not always receive universal support from the peers. Lord Carhampton, a member of the Irish House of Lords, was quoted in the Leinster Journal in 1798, suggesting that the commissioners did not necessarily serve the wider public well: ‘… as individuals; he lived amongst them in the habits of closest intimacy, nor were there men in the world with whom he would rather pass the remainder of his life as men of honour and deserved respect, but bound up together, and labelled with the title of Wide Streets Commissioners, he considered them as forming one of the most mischievous volumes extant in any country. Habitually improvident of their own private expenses, it was not very surprising if men became lavish of the public money, when trusted to their expenditure. Thousands upon thousands of the public money had already been squandered by this board, not for the purpose of opening narrow and inconvenient streets obnoxious to the city of Dublin, but with erections of new streets and squares for the accommodation of the rich.’36

Researcher Finnian O’Cionnaith sees merit in Carhampton’s contention that the commissioners favoured the rich over the poor, noting that it produced a disproportionately high number of maps of the city’s ‘more affluent and modern neighbourhoods compared to the poorer congested neighbourhoods in the south-west of the city’37 such as the Liberties.

According to Edel Sheridan-Quantz the commission was a direct result of decades of citizens’ petitions (by the upper classes residing in the Gardiner and Fitzwilliam estates rather than the working class) to the Corporation demanding improvements to the core of the city.38