28,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

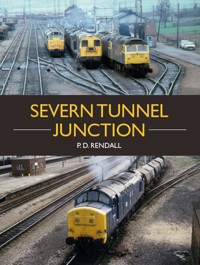

The Severn Tunnel Junction was the largest freight marshalling yard on the Western Region of British Railways, once stretching for over two miles along the Welsh bank of the River Severn. At its height it was a goods yard, junction, station and loco depot, but it was an important railway community and small town as well. With over 150 photographs this book describes the beginnings of the yard within the wider historical context and discusses the expansion of the site and the impact of the two World Wars. It documents the methods of working at the junction and recalls the locos, freight and passenger trains that travelled the lines. Finally, it remembers the people who worked and lived here.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 279

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

SEVERN TUNNEL

JUNCTION

37147 has the road away from the Down goods loop. Weeds are now beginning to encroach the reception roads… AUTHOR’S COLLECTION

SEVERN TUNNELJUNCTION

P. D. RENDALL

First published in 2020 byThe Crowood Press LtdRamsbury, MarlboroughWiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2020

© P. D. Rendall 2020

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication DataA catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 738 5

Contents

Dedication and Acknowledgements

Introduction

Chapter 1 The Beginnings

Chapter 2 Severn Tunnel Junction Station

Chapter 3 Severn Tunnel Junction Yards 1886–1936

Chapter 4 World War II

Chapter 5 Severn Tunnel Junction Yards 1945–87

Chapter 6 Methods of Working at Severn Tunnel Junction

Chapter 7 Repair and Maintenance

Chapter 8 Severn Tunnel Junction Loco Sheds

Chapter 9 The Caerwent and Sudbrook Branch Lines

Chapter 10 Signalling

Chapter 11 Railway Housing

Chapter 12 Reductions, Closures and the Future

Bibliography

Index

Dedication and Acknowledgements

To all staff who worked at ‘The Tunnel’ 1886–1987

Special thanks are due to the following who have given their time to help me with the preparation of this book:

Terry Bruton, ex-Newport panel supervisor; Peter Payne, ex-Undy hump chargeman, guard at STJ and Caldicot Crossing signalman; Graham Darby, ex-area freight assistant, Bristol TOPS 1980s; Maureen Rendall, for recalling memories of Crossway; Terry Winter, for permission to reproduce parts of his father, William Winter’s essay to STJ staff on closure of the yard in 1987; Monmouthshire County Council; the staff of the Ebbw Vale Records Office, Ebbw Vale and the Wiltshire History Centre, Chippenham, Wiltshire; Tim Rendall for loan of photographs; D. J. Tomkiss and Ray Caston of the Welsh Railway Research Circle.

Photographs by the author except where otherwise credited. All photographs are credited to the photographer where known.

Note on diagrams: Many of the diagrams and plans in this book are up to 133 years old. The quality of some of them is as can be expected for their age.

Introduction

On 12 October 1987, Severn Tunnel Junction marshalling yards were closed. The feelings of the staff then employed at Severn Tunnel Junction were summed up in a short essay written and circulated to all staff by diesel depot roster clerk, the late William Winter, on the occasion of a gathering of staff at closure.

Severn Tunnel Junction Marshalling Yards 1886–12 October 1987

Dear Colleagues,

As the Severn Tunnel Junction marshalling yards close, I cannot allow such an historic occasion to pass without expressing a few words of comment on the event.

The first railway to run through the village (of Rogiet) was the tracks of the South Wales Railway which opened for traffic the 75 miles [120km] between Chepstow and Swansea on 18 June 1850. There was no station then, as Rogiet had only a few inhabitants, mostly farmers, farm workers and a few quarrymen. This line remained alone until it was joined in 1886 by the Severn Tunnel Railway, an act of parliament for which was passed in 1872. The railway was to run the 8 miles [13km] from Pilning to Rogiet under the River Severn. You will all know the dramatic history of the building of that subsequent tunnel. It was to coincide with its opening that a station was built to be known as Severn Tunnel Junction and the first siding for the marshalling yards formed.

From that time up to and including World War I, the yards were increasing in size and use. The ‘History of the Great Western Railway’ records that traffic increased through the tunnel from 18,099 trains in 1913 to 24,027 in 1917 – mostly coal for the southern ports and docks. There was a Chief Inspector then stationed at the yard, one of whom, Mr Williams, retired in 1922. His son, Archie, who died a few years ago, was a railwayman all his working life.

Up to the end of the Great War most workers employed came from the half-circle of Magor in the west to Portskewett in the east, excluding Rogiet, although Ifton Terrace, Rogiet Terrace and Sea View Terrace had been built almost as soon as the station or very shortly afterwards. Around the same time Lord Tredegar financed the erection of the Roggiet Hotel.

The Chepstow Rural District Council built its first houses in Ifton Road and the Caldicot Road under the Housing Act 1919 and they were occupied in 1921. Shortly after this, the Great Western Garden Village Society commenced its programme of house building for railway employees with financial aid from both the Exchequer and the district council. Both these sites were the basis for the strong community spirit founded on railway service.

Sometime between the wars, a hostel was built between the station and the loco shed. This may have been purpose built but was in any case used later as a ‘double home’ lodge. At least one marriage was made in this building when a member of the female staff married a fireman and settled in a society house to raise a family.

Early in World War II, fifty concrete prefabs were built to accommodate railway personnel and for a time there were sleeping coaches in the car dock. The hostel, now the Moors hostel for homeless families, was built in 1941. Many will remember their time in residence on transferring to the depot and later settling down to family life in the area. It is believed that at the commencement of the war, 1,050 people were employed in all departments.

The first loco shed – a Great Western standard shed with four roads – was opened in what was later the car dock in 1908 followed by the opening of the new shed in, I believe, 1921. My father worked in the former shed until dismissed in 1911 for smoking on the footplate. He then joined the regular army until invalided out in 1919. Later he again worked on the railway as a platelayer in the tunnel from 1935 to 1937.

In 1947, one year before nationalization, a census of engines revealed Severn Tunnel Junction as being the third in the table of totals in the old Newport Division with ninety-three. Ebbw Junction was top with 140 followed by Canton with 121.

From the turn of the century until 1963 all was expansion and consolidation. When I started work the Great Western Railway still had six years to run, although the paternalism of that railway was inevitably under strain during the war years. Following nationalization almost imperceptibly things began to change. This continued until Dr Beeching decided that the railways as we knew them would never be the same again. Not content with the closure of so many lines, he seemed determined that, however the climate changed in future years, there would be no opportunity for expansion should the need arise.

The appointment of Dr Beeching, however, may have been a consequence of the increase in private car ownership and the massive motorway building programme to accommodate the ever increasing number of lorries, which were also becoming larger in size and axle weight. The ‘dream’ following nationalization of a fully integrated transport system never came to fruition due to the failure of all governments to stand up to the road lobby and insist on its implementation. Until 1963, through two world wars, every small lineside factory had its own sidings forming brooks, which formed streams until, reaching marshalling yards like ours, formed rivers of traffic of all descriptions being delivered without problems. BR now seem to lose in the competition, with fewer trains chasing fewer goods available to both, leading to the need for reductions in staff.

The railway was always in our consciousness from an early age. The whistle of a train heard on a restless night. The clang-clang of steel wagons buffering up against others off the hump. The whistles of the engines welcoming in each New Year.

A Sunday evening walk with my family sometimes brought us over the railway bridge from the Moors. This always seemed to coincide with the passing of the Carmarthen milk train. Milk traffic commenced in the 1880s, with the liquid being carried in thousands of churns in open trucks until, in 1906, the first glass-lined 3,000-gallon tankers were brought into use. Traffic now lost, as are the fish trains which I used to shunt with the fish pilot, killed by the formation of the deep freezing industry. Cigarette and chocolate traffic carried through the tunnel on the 8.08pm Bristol– Manchester for many years are other goods that have gone.

I have heard it said that all people coming to work at the depot are accepted without question or reservation. Perhaps I have indicated our long history of acceptance into our working community, and, where appropriate, our domestic environment. There are still examples in the area of long-term service on the railway in addition to all those who followed their grandfathers.

For example, Ken Margrett’s great-grandfather was a signalman, his grandfather was the Chief Inspector mentioned earlier who retired in 1922 and his father, Bill, was a driver before him. Another is a sprightly ninety-one-year-old exforeman, Mr Jack May, whose father was a chief inspector at Aberbeeg. His son, Herbert, has just retired as a supervisor and his granddaughter is in higher management on the Eastern Region. This latter is an indication of the changing attitudes brought about by various sex discrimination laws.

It is, perhaps, invidious of me to mention people as I have not the time or memory to recall all the varying characters I have met and worked with over the years. I may be forgiven, however, if I mention some of those from my early years. My first Station Master for instance, Mr Richard ‘Dicky’ George. He was a great fan of the hunting field and, in 1938, under a title ‘Station Master George goes Hunting every Monday’ an article appeared in the Daily Express about him. What the directors may have thought I cannot imagine, but it may have been considered a public relations exercise. There was Jack Davies, ‘Top End’ Inspector, who was so annoyed at the slowness of his signalman in the Middle box, George Foulkes, to transfer bankers from arrival trains to departure that he wrote a long poem about him. One does not know if this failure to work quickly was plain laziness or downright awkwardness for he (Foulkes) was very eccentric. I suspect the former as George liked a little nap on the night turn.

My second mate, with whom I worked for five years, must be mentioned. This was Bill Andrews, the Timekeeper in the office which once stood on the site of the present amenity block. Bill had lost a leg at the time of World War I when attempting to jump on a brake van to get to work. The vehicle had no step, being a plough van, which caused the accident in the darkness. Following his return to work he was employed for eighteen years on nights in the Newport telegraph office, before returning to the depot. Bill was an expert on all types of engines, particularly that of his Ariel Square Four motorcycle. I remember Chief Inspector Jenkins from Swindon always visited him when at the depot to talk about the latest development of steam engines. Bill I remember as a very great gentleman.

My first mate, for a short while, was Inspector Raffel, an expert gardener whose brother was a head gardener at Kew. Before I worked with him he used to sport a beard and there’s a rude story about him which I cannot repeat here in relation to his nickname of ‘Beaver’. When I worked with him he had a walrus moustache and chewed twist. The surplus juices were usually deposited in the mouthpiece of the telephone during a long conversation or spat accurately to fry on the top of the red hot stove in the corner of the office.

I remember Guard Albert Edwards who, no matter what time of night he booked off duty, would always wait for someone to ride home with him to Magor as he was reluctant to pass the barn at Llanviangel, believing it to be haunted.

Then there were the prodigious users of expletives, Stan Powell and Ivor Pritchard, who could string four letter words together like pearls in a necklace. These two were exceptional in what is generally a swearing industry. And finally, Signalman Ted Pippin, who, dressed one night as an Indian Brave, relieved his mate Fred Boon at 10pm having left a fancy dress dance early as Fred would not stay on for him.

Tales could be told of so many more, such as Horace Edwards, Bill Sheppard, Charlie Avery, Adrian ‘Doctor’ Crawley etc. The list of personalities is endless, but time and space does not allow such liberties.

From 12 October all that will be left will be memories. Some of you – most I hope – will have happy ones. Some, a few who may have been involved in accidents or other incidents, may have memories they would rather forget. All I believe must have experienced something of an attachment to the depot that will remain with you wherever you go or how long you live in retirement.

My own particular memories are the day I started work learning duties in the Bristol yard on 21 December 1941, having left school at the age of fourteen the Friday before. I was allowed Christmas Day off but had to report for work on Boxing Day. I remember seeing my first fatality when I found Guard Tozer of Maesglas dead across the rail early one wet June morning in 1943. Another memory is the camaraderie of the Down side shunting gang, particularly on a wet night with the rain driving in from the moors. Strangely enough, one never seemed to get so wet and miserable whilst working all night as one felt after one or two hours in daytime. And later, when on light duties in East box, I well remember the sound of bird song in the very early morning in spring, mixed with the slight hiss of steam from an engine waiting at the shed signal. For our depot is possibly unique in the whole BR system in that, except where it is touched by the few houses in the area of the church, the vast acres of the yards are entirely surrounded by countryside.

And so, after 101 years, an era ends, and the railway through Rogiet reverts to the line of the Severn Tunnel Railway. When the yard rails are recovered, all that will remain for the hard work, spirit and dedication of countless men and women over generations will be one unmanned passenger station. In this high-tech age of computers and microchips I wonder what industry could replace the railway in which we could prove that our children and our children’s children were able, in the next hundred years, to build on the traditions of the past.

Whilst it is true that you will meet Mr Davidson (Area Manager) for a farewell interview if you are leaving the service, this may not be enough for some as there are several strong emotions to consider. Frustration for instance, that you could do nothing to prevent the loss of your jobs. Anger that your life’s work has gone and that some of you must leave earlier than you would wish, and others uproot their homes and families and find jobs at other depots where you may find the atmosphere will not be as relaxed as ours has been. And finally, deep sadness at the loss of the friendship and companionship of your mates. True, friendships can continue, if loyal, but it will not be the same as the levity of cabin life and the ‘All OK, mate’ when relieving each other on engine or brake van.

I trust it will not be thought presumptuous of me, therefore, to supplement what the Area Manager may say to you, with these words of my own. I feel qualified with my long service to the community and depot and by my long association with you, to do so.

I am leaving after forty-six years and in farewell would like to say how much I have enjoyed working with you. To those with whom I attended school and who started work around the same time in the war, all who subsequently joined and those of you who came from Ebbw Junction that October Sunday in 1982 with, perhaps, some trepidation, believing you were arriving at a depot where you could work contentedly until retirement. Some of these, I believe, will have regrets that they cannot stay and may even wish they had joined our ‘family’ earlier.

I am grateful for the privilege of working for the Great Western and BR as, whatever the circumstances that can be levelled, the industry, as far as I know, never failed to look after staff who had fallen down in health in some way, and were found alternative positions.

Whether you are retiring or have found a new depot at which to work, I wish you all good luck and all the very best in health, happiness and prosperity, especially the former, for without that, the other two are meaningless. To close, perhaps a quotation from Lord Lytton would be apt:

Ah, Never can fall from the days that have been A gleam on the years that shall be…

W. C. Winter, 1 September 1987

Two miles (3km) inland from the small village of Portskewett on the Welsh side of the River Severn, 4 miles (6km) southwest of the town of Chepstow and 4 miles (6km) east of Newport was what was once the largest goods marshalling yard in the area once run by the Great Western Railway Company. It lay just a few hundred yards of where, until 2019, stood the toll booths of the M4 motorway. The River Severn itself was, at its closest to the yards, a mere quarter of a mile (400m) away.

This was Severn Tunnel Junction; a name now known to twenty-first-century commuters as an unstaffed junction station on the South Wales main line in Monmouthshire, but to older railwaymen and women and railway enthusiasts it was the site of the largest freight marshalling yard in the Western Region of British Railways. At its height, it boasted four yards and a locomotive depot, and stretched for over 2 miles (3km) along the Welsh bank of the River Severn between the town of Caldicot and the village of Undy. Opened in 1886 along with the Severn Tunnel, the yard was the hub of freight traffic for South Wales. Enlarged in 1930, when it became a ‘hump’ yard, enlarged again in 1937 and once more in 1960, it was finally closed in 1987 and most of the traffic that once passed through ‘STJ’ was either lost all together or moved onto the roads. In the past, to many railway enthusiasts and photographers, Severn Tunnel Junction meant a vast railway marshalling and hump yard first, and a station and junction between the Gloucester and Bristol main lines second, with the steam loco and (later) diesel depot third.

In order to understand the working of the yards and loco depot, plus the community that sprang up around them, it is necessary to take into account the approaches to the yards from either side. Thus this book will take in an area bounded by Bishton to the west, and on the east side, Caldicot Junction on the Gloucester lines and Severn Tunnel East signal box on the London lines and the English side of the river. Also included, as both were of importance to Severn Tunnel Junction, will be the short branch to Sudbrook and the longer branch to Caerwent Royal Navy depot.

It’s important to remember that Severn Tunnel Junction yard wasn’t just a railway yard, junction, station and loco depot. As the reader can see from William Winter’s words above, Severn Tunnel Junction was a railway community; the village of Rogiet was taken over by railway staff who moved there to take jobs at the ‘Junction’. Houses were built by and for them, making the one-time hamlet into a small town.

This is its story.

CHAPTER 1

The Beginnings

The year 1870 had begun with mixed prospects. In Europe, the Prussian prime minister, Otto von Bismarck, was whipping up nationalistic fervour in order to unite the independent German states with Prussia. The French were against such ideas and this led to the Franco-Prussian War, which started in July 1870. In the United Kingdom, Queen Victoria was continuing to rule alone; her consort, Prince Albert, had been dead for nine years and Victoria was still in mourning. It was not all gloom though. Joseph Lister had invented the sterilization process for surgical instruments and the Education Act had been passed.

In Britain, the railway age was in full swing. Whilst many railway lines and companies were making their presence felt in the country, in the southwest of the UK the Great Western Railway was finding things difficult. Brunel, its iconic engineer, had been dead for eleven years. Brunel’s engineer Daniel Gooch still held the flag for the GW ‘old guard’ but his age was telling on him. The company may have boasted the longest main line in the country, but there was the ongoing ‘Battle of the Gauges’: Brunel’s ‘out on a limb’ broad gauge versus Stephenson’s almost universally adopted narrow (4ft 8.5in) gauge. The broad gauge was losing and large parts of the GW network were already ‘mixed gauge’.

Elsewhere on the GWR system, capacity was challenged by the fast-growing coal industry. Economics dictated where many of the new lines went and this was especially so in South Wales, where the economic mainstay was coal. South Wales, having outstripped the north of England for coal production (at the expense of the men and boys working in the mines), was on its way to becoming the biggest exporter of coal in the world. Railways not only moved the stuff but railway locomotives would become one of the largest users along with domestic markets.

The South Wales Railway

The GWR began moving coal by rail out of South Wales. It had its line out of South Wales, the South Wales railway (now the main line from Gloucester to Swansea via Chepstow), which had opened between Chepstow and Swansea in 1850. This was initially a main line of two parts, with another section of the South Wales Railway running from Gloucester to, at first, Grange Court, along the western bank of the Severn and then to a temporary station on the Gloucester side of Chepstow. The ‘missing link’ was a bridge over the River Wye. The poor old passengers had to detrain and cross the river by means of a road bridge until Brunel successfully bridged the Wye with his unique suspension bridge, and the railway, now owned by the Great Western, opened throughout on 19 July 1852.

An old print showing Brunel’s unique bridge at Chepstow, which completed the missing link in the South Wales Railway. It was replaced in the 1950s.

From picturesque Chepstow the line took a sharp turn to the southeast and followed the River Wye before turning southwest and following the coast for a couple of miles and turning slightly inland towards Newport just after the village of Portskewett, where a small station was built. This line was, for a time, adequate for goods traffic, but not for passengers. It could take a couple of days to travel from Cardiff or Newport to Gloucester and from Gloucester to the rest of the GW system or to a port, for example Southampton. Not for nothing had the GWR been given the nickname of ‘Great Way Round’.

Crossing the Severn

The GWR sought to alleviate the delays and to speed up the movement of coal traffic and passengers into and (mainly) out of South Wales. But there was a snag: the River Severn. Not the widest or deepest river in the country, the Severn was, perhaps, the most unpredictable. There was the problem of the tides, for example: the Severn had the second highest rise and fall of tides in the world: 14ft (4m) on average, up to 50ft (15m) on those occasions when the famous tidal wave known as the Severn Bore rushes up the river. Then there were numerous underground springs, mudbanks and deep freshwater pools. Crossing the river was not an easy challenge to overcome. Engineers wrung their hands in despair at the thought of building a bridge.

The River Severn. It has the second highest rise and fall of tides in the world. The fishermen are on the old Beachley–Aust ferry landing stage.

Whilst this industrial wringing of hands was going on, the Bristol and South Wales Union Railway was built from Bristol to New Passage on the English banks of the Severn, opening in 1863. A pier was built and from here passengers could detrain and embark on a ship to cross the river. This was fine as long as the weather and the tides played ball, and the new Passage Hotel built nearby was in much demand on such occasions when they didn’t. This service could also only carry passengers, not goods.

Those engineers, meanwhile, had stopped wringing their hands long enough to produce plans for bridges over the Severn. They needed to be high bridges, because ships (which in those days had high masts carrying sails) needed to be able to pass underneath on their way upriver to Sharpness and Gloucester docks. One engineer, Sir John Fowler, planned such a bridge: 100ft (30m) above high water and 2.75 miles (4.4km) long, it would stride across the Severn. Possibly out of a sense of desperation, the GWR board of directors approved this bridge in 1865.

Bridge or Tunnel?

Like all such schemes, it took time to draw plans and survey ground, and by 1870, whilst the world – and other railway companies – was moving on, the GWR found themselves treading water. The South Wales coalfields, having been tapped, were now gushing and if the GWR didn’t get their act in order, they could well lose out to rivals. The LNWR had already made inroads into the South Wales coalfields. The bridge was still the preferred option but all the time another voice was advocating a plan that could reduce the travelling distance between South Wales and Southampton by 61 miles (98km). It could knock an hour off the journey time between Cardiff and London and wouldn’t need to be at the mercy of high tides and tall ships. It all came about because of an idea to speed up railway services between South Wales and the rest of the United Kingdom, and the idea was a tunnel: a tunnel under the mighty River Severn.

The Welsh side of the Severn Tunnel was approached via a deep rocky cutting. This illustration is from an old commemorative cigarette card.

Whilst many engineers had balked at the idea of tunnelling under the Severn, one man, Charles Richardson, surveyed the route and planned his tunnel. The route would run from Pilning (where it would leave the course of the Bristol and South Wales Union line) and descend through a deepening cutting until plunging into a tunnel under the River Severn at a falling gradient of 1 in 100, changing to a rising gradient of 1 in 100 halfway through, and rising up to emerge into another deep cutting near Caldicot. This line would meet the line from Gloucester at a place called Rogiet on the Monmouthshire side of the river. The new line would be almost 8 miles (13km) long, of which 4 miles 624 yards (7km) were to be in tunnel, 2.25 miles (3.6km) of which would be underneath the River Severn.

Daniel Gooch and the GW board listened to Richardson and liked what they heard. The bridge plans were dropped. Richardson’s plans were deposited in 1871 and the tunnel got its Act of Parliament in 1872. Work commenced in 1873 and, thirteen years later, Daniel Gooch was one of the people who rode on the first train to pass through the tunnel from west to east on 5 September 1885, after completion of the works. The tunnel opened for goods traffic in 1886. On 9 January 1886, an experimental coal train ran from Aberdare to Southampton through the tunnel, with the result that coal was delivered at the port in the evening of the same day. The opening for traffic was delayed pending completion of the new pumping station arrangements at Sudbrook, to contain the underground river known as the ‘Great Spring’, which had broken into and flooded the workings during construction. The Sudbrook pumps moved approximately 30 million gallons (136 million litres) of water a day (seeChapter 9).

On 1 September 1886, the line was opened for goods traffic and passenger trains began to run between Bristol and Cardiff three months later. The new line and tunnel cut 60 miles (97km) off the journey between London and Cardiff. This was shortened further in 1904 by the opening of the South Wales Direct line between Wootton Bassett and Patchway.

The junction of the Gloucester–Newport lines with those of the new lines from Bristol was near Rogiet. At the time the South Wales Railway Gloucester–Newport line arrived in the area in 1850, Rogiet was merely a tiny hamlet on the ‘Caldicot Levels’ – the flat lands just inland of the River Severn. Rogiet was at that time a village and community in Gwent (now Monmouthshire), southeast Wales, between Caldicot and Magor. It is 8 miles (13km) west of Chepstow and 11 miles (18km) east of Newport. The area also encompasses the hamlet and separate parish of Llanfihangel Rogiet (located immediately west of Rogiet and which derives its name from the Welsh name for the church of St Michael) and the land immediately east of Rogiet, which once formed the separate small parish of Ifton. The origin of the name Rogiet is not known and it has been spelt ‘Roggiatt’, ‘Roggiett’ or ‘Roggiet’ in its time, the latter two variations being used within living memory. The church of St Mary is the parish church. (An earlier dedication was apparently to St Hilary, a man who seems to have little connection with South Wales other than being thought of highly by St Augustine, who apparently held him in some esteem. St Augustine, of course, is said to have held a conference with early British bishops at Aust, on the English side of the Severn, in AD 603.) Much of the church dates from about the fourteenth century.

Much has been written about the construction of the Severn Tunnel and I do not propose to go over old ground; however, its working is part of the story of Severn Tunnel Junction. The completion of the tunnel under the Severn proved to be a winner so far as the fortunes of the GWR in the South Wales area were concerned. Yet, whilst its existence brought many benefits to the Great Western and unlocked the potential of South Wales traffic, being 4.5 miles (7km) long and double track between Severn Tunnel Junction on the Welsh side of the River Severn and Pilning on the English side, once the tunnel began to be heavily used it proved a bottleneck. Over the years goods loops were added at both sides of the tunnel but that 4.5-mile (7km) block section was a pinch point; slow freight trains could take 10 minutes to pass through the tunnel. As I mention later in the book, intermediate block signals were often contemplated to break the long section, but any proposed benefits were always outweighed by the horror of a collision in the tunnel; it took a world war to change that way of thinking, but only whilst the crisis was ongoing (seeChapter 4).

EXTRACT FROM KELLY’S LOCAL DIRECTORY OF MONMOUTHSHIRE 1901

ROGGIETT (Severn Tunnel Junction station on the Great Western Railway South Wales line) is a parish on the shore of the Bristol Channel 7½ miles southwest from Chepstow, and 142½ from London, in the Southern division of the county, hundred of Caldicot, petty sessional division, union and county court district of Chepstow, rural deanery of Netherwent, archdeaconry of Monmouth, and diocese of Llandaff.

CHAPTER 2

Severn Tunnel Junction Station