Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Icon Books

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

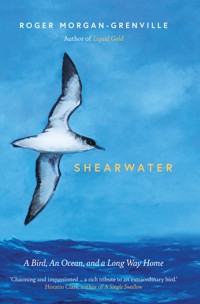

'Shearwater is sheer delight, a luminous portrait of a magical seabird which spans the watery globe' Daily Mail. 'Charming and impassioned ... a rich tribute to an extraordinary bird.' Horatio Clare, author of A Single Swallow and Heavy Light. A very personal mix of memoir and natural history from the author of Liquid Gold. Ten weeks into its life, a Manx shearwater chick will emerge from its burrow and fly 8,000 miles from the west coast of the British Isles to the South Atlantic. It will be unlikely to touch land again for four years. Part memoir, part homage to wilderness, Shearwater traces the author's 50-year obsession with one of nature's supreme travellers. In the finest tradition of nature writing, Roger Morgan-Grenville, author of Liquid Gold - described by Mary Colwell (Curlew Moon) as 'a book that ignites joy and warmth' - unpicks the science behind its incredible journey; and into the story of a year in the shearwater's life, he threads the inspirational influence of his Hebridean grandmother who instilled in him a love of wild places and wild animals. Full of lightly-worn knowledge, acute human observation and self-deprecating humour, Shearwater brings to life a truly mysterious and charismatic bird.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 392

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Praise for Shearwater

‘This charming and impassioned book meanders, shearwater-like, across a lifetime and a world, a rich tribute to an extraordinary bird drawn through tender memoir and dauntless travel.’

Horatio Clare, author of A Single Swallow

‘This is wonderful: written with light and love. A tonic for these times.’

Stephen Rutt, author of The Seafarers: A Journey Among Birds

‘What I love about Roger Morgan-Grenville’s writing is the sheer humanness of it … There are environmental issues and pure natural history in here, but the overall feel of the book is simple, humble wonder. Roger was lucky to have a grandmother who knew how to gently foster a live-wire mind. She loved birds, she loved Roger, and the combination guided him to her way of thinking as he grew older – and this odyssey for shearwaters is the result. Bravo – a truly lovely book.’

Mary Colwell, author of Curlew Moon

‘Shearwater is a delightful and informative account of a lifelong passion for seabirds, as the author travels around the globe in pursuit of these enigmatic creatures.’

Stephen Moss, naturalist and author of The Swallow: A Biography

‘A memoir lit by wry humour and vivid prose … his evocation of the Hebrides is as true as the fresh-caught mackerel fried in oatmeal his grandmother used to cook for him.’

Brian Jackman, author of Wild About Britain

Praise for Liquid Gold, by the same author

‘A great book. Painstakingly researched, but humorous, sensitive and full of wisdom. I’m on the verge of getting some bees as a consequence of reading the book.’

Chris Stewart, author of Driving Over Lemons

‘A light-hearted account of midlife, a yearning for adventure, the plight of bees, the quest for “liquid gold” and, above all, friendship.’

Sunday Telegraph

‘Liquid Gold is a book that ignites joy and warmth through a layered and honest appraisal of bee-keeping. Roger Morgan-Grenville deftly brings to the fore the fascinating life of bees but he also presents in touching and amusing anecdotes the mind-bending complexities and frustrations of getting honey from them. But like any well-told story from time immemorial, he weaves throughout a silken thread, a personal narrative that is at once self-effacing, honest and very human. In this book you will not only meet the wonder of bees but the human behind the words.’

Mary Colwell, author of Curlew Moon

‘Beekeeping builds from lark to revelation in this carefully observed story of midlife friendship. Filled with humour and surprising insight, Liquid Gold is as richly rewarding as its namesake. Highly recommended.’

Thor Hanson, author of Buzz: The Nature and Necessityof Bees

‘Behind the self-deprecating humour, Morgan-Grenville’s childlike passion for beekeeping lights up every page. His bees are a conduit to a connection with nature that lends fresh meaning to his life. His bee-keeping, meanwhile, proves both a means of iiiescape from the grim state of the world and a positive way of doing something about it. We could probably all do with some of that.’

Dixe Wills, BBC Countryfile Magazine

‘Peppered with fascinating facts about bees, Liquid Gold is a compelling and entertaining insight into the life of the beekeeper. But it’s much more than that. It’s the story of a life at a crossroads when a series of random events sets the author off on a different, and more satisfying, path. It’s a tale of friendship and fulfilment, stings and setbacks, successes and failures and finding meaning in midlife.’

WI Life

‘[A] delightfully told story … Wryly humorous with fascinating facts about bees, it charts the author’s own mid-life story and the joys of making discoveries.’

Choice magazine

‘The reader will learn plenty about bees and beekeeping from this book, although it is about as far from a manual as possible. Liquid Gold is a well observed delve into the hobbyist’s desire to find what is important in life, no matter their age or preparedness.’

The Irish News

‘[A] delightful exploration of the world of bees and their honey … a hymn to the life-enhancing connection with the natural world that helped Morgan-Grenville reconcile himself to the fading of the light that is middle age.’

Country & Town House magazine

‘Both humorous and emotionally affecting … Morgan-Grenville’s wry and thoughtful tale demonstrates why an item many take for granted should, in fact, be regarded as liquid gold.’

Publishers Weekly

SHEARWATER

A Bird, An Ocean, and a Long Way Home

ROGER MORGAN-GRENVILLE

CONTENTS

In memory of Elizabeth Freeman 1912–1986

Dedicated to the small army of scientists, zoologists, conservationists, policy-makers, wardens, charity workers and volunteers whose work helps to explain our wildlife to us, and ensures as best it can that it will still be there for our children and grandchildren to cherish.

A NOTE ON NAMES

Most of the names and places in this book are the real ones. Following seabirds is, however, generally a private activity, and I have occasionally protected the identities of the people I met on my travels by changing their names.

MAPS

xiv

1. The western British Isles, showing main breeding sites (Chapter 4) and other places mentioned in the book.

xv

2. The Atlantic Ocean showing gyres and migration routes (Chapter 7).

xvi

3. The Hebridean ‘Small Islands’ (Chapter 11).

PROLOGUE

Wrong End of the World

May 2004, Tsu City, Japan

From a certain point onward there is no longer any turning back. That is the point that must be reached.

Franz Kafka

All bird species have occasional vagrants, members of the clan who, for one reason or another, find themselves in entirely the wrong place.

It might be because of fog or a strong and relentless wind; it might be some fault in the bird’s navigational wiring, or that it simply found itself far out at sea, alighted on a passing ship and then ended up wherever the ship happened to be going.

The vagrants we tend to see in the British Isles are often blown over the 3,000-mile Atlantic Ocean by a prevailing gale, or pushed up from the Sahara on the forward edge of a sandstorm. Our most famous vagrant was probably ‘Albert Ross’, a black-browed albatross who kept his lonely vigil around Bass Rock in eastern Scotland on and off for 40 years from the mid-1960s, his romantic advances among the gannets constantly fated to refusal and failure. It wasn’t the fact that he xviii was 6,000 miles away from the northern end of his range that was astonishing – it was that he would have had to cross the equator and the tropics at some point to be here. Albatrosses need wind for their dynamic soaring flight and the tropics, as the Ancient Mariner found out to his cost, often don’t have any.

One morning in mid-May 2004, a Japanese fisherman noticed a bird he didn’t recognise just off the shoreline at Tsu City, a small industrial town a couple of hundred miles to the west of Tokyo. He was interested enough to bring it to the attention of one of Japan’s most dedicated seabird experts, Hiroyuki Tanoi, who quickly and positively identified it as a Manx shearwater, photographing it for good measure to convince any doubters.

And doubters there absolutely would have been. For the Manx shearwater is a bird of the Atlantic, not the Pacific, breeding in the north of it from March to September, and then fishing under the Latin American sunshine for the rest of the year. Indeed, if you take the central point of the bird’s southern range, somewhere off the coastal waters where Brazil, Argentina and Uruguay meet, and drill a line through to the opposite side of the planet, you will arrive in Tsu City, Japan. Meaning that this shearwater was a full 13,000 miles out of its range and on exactly the wrong side of the world, a distance that no vagrant in history has been recorded achieving. In fact, if you wanted to make a point, it was precisely in the one place that it really shouldn’t have been, looking sleek and healthy, calmly fishing away as if it was off the Valdés Peninsula, or the Irish coast. Disorientated it may have been, but distressed it certainly wasn’t. xix

To get to Japan, it would have had to do one of two things. Either it flew all the way down to Cape Horn, rounded it, and flew up the long western coast of South America until it got to Peru and allowed one of the prevailing winds to blow it across the small matter of the entire Pacific Ocean. Or it flew across the Atlantic, rounded the Cape of Good Hope, worked its way across the whole Indian Ocean until it got to Australia and then headed up through the Philippine Sea and thence to Japan. Every single mile in the wrong direction. Every single day, presumably, on its own. Maybe 40 or 50 days, fishing trips included.

It was May, and therefore the breeding season. And while there are other shearwaters on the Japanese coast, they are not ones with which a Manx could interbreed. So he or she (they never found out which) simply flew low over the beach houses at night making the eerie ‘devil’ call for which they are famous back in their British breeding grounds, looking for a mate or, worse still, searching for an imaginary chick. At one particular house, it kept striking the awning of the balcony and then landing, until the kindly owner took it in to protect it from the local cats, and released it to fly the next day.

The shearwater stuck around for two months until the night of July 13th when it disappeared for good, presumably working out simultaneously that raising a chick by the end of the season was unlikely, and that it had a bit of a commute ahead of it to get back home.

With no ring and no tracking information, we don’t know exactly what happened to it; although, with a 92% survival rate between years for adult shearwaters, there is a reasonable chance that it at least got back to more familiar shores. xx

I tracked down Mr Tanoi, who turned out to remember every detail, and he sent me the photographs he had taken. He also told me that almost exactly seven years later, on July 16th 2011, another one had been identified from a ferry off the coast of Miyagi Prefecture, well up to the north of the country, but then no more.

We may not know any further details about that Tsu City bird, but we can guess with some certainty that she (if that is what we would like her to be) had once emerged from an egg inside a burrow on an island off the west coast of Britain and Ireland, and that, after 60 days or so, her parents quietly abandoned her. We know that ten days later, starving and having lost 30% of her body weight and preened her own downy feathers away, she would have stumbled out of her burrow one windy night, found the highest point in reasonable proximity, flapped her wings and risen up into the darkness. We know that from that point she would not have touched land again for four years or more, and that she would have ceaselessly roamed the oceans, possibly covering 40,000 miles each year.

We know that, on her first flight, a mix of genetic coding, smell, sight, sound, sun, stars and magnetic field would have guided her, not yet ten weeks old, down past the Bay of Biscay, past the dusty coast of Morocco and the Canary Islands, and down to Senegal, fishing from time to time, but mainly travelling. To put this in a human context, it is the equivalent of a four-month-old baby walking out of the house to make its own way in the world. We know that the shearwater would then have instinctively caught the helpful South Atlantic gyre, whose winds would have pushed her over to Brazil and then down the coast xxi to Argentina, and the rich fishing grounds between there and the Falklands. We know that she would have gone through her rites of passage in the western Atlantic, laying down a mind map of the ocean and its fishing grounds, the better to prepare her for motherhood when changing hormones would drive her to the north-east one early spring. And that she would search for a mate and reclaim her burrow, probably no more than a few yards from where she was born, and thus continue the circle of life.

For as long as I can remember, I have chased her, more often in my imagination than out at sea. Schoolboy, soldier, trader, charity worker and writer: through all of those phases of my life she has been my metaphor for wilderness and adventure, always free, always out there, always just beyond reach.

The Manx shearwater is one of nature’s near-perfect fliers. She is not a soaring bird of the heavens so much as a bustling presence low down on the salty horizons, a crosser of seascapes glimpsed from the stern of faraway vessels. From the structure and length of her wings to her ability to smell a potential meal ten miles upwind, from the desalination plant within her beak to her exquisitely complex navigational systems, she is a creature fully of air and water. Related to, but much smaller than the similar albatross, we know that she actually uses less energy flying through the air than she does resting on the water. Just as the camel has evolved as the supreme desert animal, so the shearwater has spent 120 million years perfecting the life of an ocean wanderer.

Out there, a few feet above the waves and beyond all human comforts, the shearwater is utterly at home.

This is the story of my 50-year search for her.

PART ONE

OUTWARD BOUND

1. THE 83RD BIRD

1971, Isle of Mull

There is no such thing as the pursuit of happiness, but there is the discovery of joy.

Joyce Grenfell

In the summer of 1971, Tuesdays were our puffin days.

Puffins were the natural history offerings of my childhood summers, on which it had been almost impossible to overindulge. Puffins were birdwatching made manifestly and childishly joyful, a pound of comic sweetness with sad clown’s eyes, Charlie Chaplin walk and outsize colourful bill. Back then, when there was little talk of global warming, of struggling sand eel populations, or of decline, my sister and I just had an uncomplicated fascination with a creature that seemed more burlesque than seabird, and whose mannerisms somehow made us exquisitely happy. 4

We spent the middle part of each summer at my grandmother’s little Hebridean croft on the southern tip of the Isle of Mull, and at least once or twice each holiday she would get Callum the Boat to take us all over to the waters around Staffa to find them. Everyone on Mull seemed to have a handle back then, or at least they did to my grandmother: Angus the Coal, Glen the Store, Ian the Park. No one was entirely sure what Ian the Park did, but we used to find him in the late afternoons behind my grandmother’s woodshed, passed out in a haze of cheap whisky, when she was paying him to sort out the fencing for her. In theory, he did the jobs around the place that she was no longer strong enough to do; in practice, he was a lame duck she couldn’t bear to evict from under her wings. He knew it, she knew it, we knew it, and the knowledge of it changed nothing.

‘Oh, he’s got rather a lot on his mind,’ she would tell my sister and me when we reported the state he was in, as if that explained everything.

Other children may have had more obviously exotic holidays, but our trips to Mull were the integral hard landscaping in the garden of our young summers. The expression ‘work hard, play hard’ could have been invented for these stays, where mornings might be spent pulling ragwort from the stony field beyond the garden wall (a penny paid for proof of a dozen roots), carting sacks of seaweed up the rocky path to pile onto the vegetables, cutting tracks through the bracken in the hilly wood behind the house. But the payback for mornings of graft was the uncompromised availability of my grandmother for afternoon adventures, bundling along to favoured beaches to swim with the seals, climbing hills and settling in for tea with her eccentric array of 5 widow friends dotted around the island. Often, these wanderings took us to the neighbouring holy island of Iona, where we would endlessly harvest the sea-smoothed white and green marble pebbles on St Columba’s Bay, pebbles which even now sit on the terrace outside my Sussex kitchen door.

The tacit deal was that we understood our place in the pecking order – after the dogs but before the birds – and that we did our full share of the chores. She was more gang-leader than grandparent, as relentless at galvanising activity as she was a calm evening listener to childhood and teenage problems. Into the mix came a variety of bizarre activities that would now have any adventure training centre closed down on the spot – chainsawing logs without protection at the age of fourteen comes to mind – but we ate well, exercised massively and slept like happy corpses when each day was done. Those early summers of a life etch into memory their unforgettable colours: the blue hills beyond Bunessan, the speckled pink of the granite rock and the black-brown squelching ooze of the bog out there beyond the Ardfenaig sheep fank. And always the permanent but ever-changing presence of the surrounding sea and its raucous birds. Selective memory insists that it was just about always sunny, even when it wasn’t, and that there were never midges, even when there were.

Sea and shorebirds, together with the relentless wind, that was the soundtrack of our times there, and it started on our very doorstep. The four-note monotone tutting of the resident great black-backed gulls, Laurel and Hardy, as they sat patiently on the cottage roof when nothing was happening, followed by their yelping long-calls when they spotted food. As children, there 6 was nothing we weren’t prepared to feed them when nobody else was looking; as gulls, there was nothing they would refuse. Gulls can live for over 25 years, so they eventually became as much of a fixture of the place as my grandmother, or Robin at the petrol pump on the way to Fionnphort, and we would politely ask after them in our letters, as if they were family. Out on the marshes between Loch Caol and Market Bay we would hear the trill of oystercatchers and the mew of the hunting buzzards. On the cliffs it would be the high notes of the golden eagle and then over on the evening sea-lochs, the maniacal cry of a single great northern diver. Best of all was that simultaneously life-enhancing and mournful call of the curlew, an expression of wilderness joy, or maybe an elegy for extinctions yet to come. Little by little, and without my ever knowing it, the sounds embedded themselves in a part of my soul that I was still too young to comprehend, or to access at will.

Generally, my parents would leave us, and her, to it, perhaps understanding the safety valve effect of a period of separation in a long summer school holiday. This meant that the adventure started with the allocation of the ‘unaccompanied minor’ badge on the BEA flight up from London, and only ended when my parents arrived for the last week of our stay. It was not that we didn’t do adventures with them, it was just that they were different ones, with different rules and hierarchies. Mull simply gave my sister, my cousins and me the chance to go feral for a short period of time, and feral is what children do most naturally, if machinery and adults don’t get to them first.

Chicken paste sandwiches in greaseproof paper, apples and Penguin biscuits were our staple diet for days out, chased 7 down by whatever cordial my grandmother had recently made. Sometimes, she would take along a couple of cans of Tennent’s lager to share with Callum, or whoever we were spending the day with. Depending on how she felt, she would let one of us drive her old Land Rover the three miles to Fionnphort Pier, while she sat in the passenger seat playing ‘Clementine’ or Tom Lehrer’s ‘We Will All Go Together When We Go’ on a mouth organ she kept wrapped in a bandana in the glove compartment. For a boy whose coltish legs hardly reached the pedals, this illegal preface to the puffin day was so good as to be a tiny glimpse into the very backyard of heaven. The deal on both sides was that my father was never to know what we got up to when we were staying with her. Given that this regularly included being sent out to fish for mackerel for breakfast, without life-jackets, in her little boat on the adjacent sea loch, it was probably just as well.

‘It’ll be the puffins you’ll be wanting to see again, I suppose,’ Callum would sigh as we decanted ourselves and our kit from the pier onto his fishing boat. ‘I’d say you’re leaving it a wee bit late again this year.’ It was his mournful catchphrase, and he probably would have said it whenever we had come, and whatever we were looking for. Whatever else Callum had been put on earth for, it was not as a bringer of joy.

The essential problem was that schools down south, where we lived, didn’t break up until well into July, by which time most of the pelagic* birds we were looking for were starting to 8head back out to sea. The best of the watching is gone by then, and what remains is down to luck and the prevailing weather.

I helped Callum cast off from the rusty iron ring on the pier, pleased to be publicly useful in such a physically undemanding way. The familiar smell of Callum’s boat, a mixture of diesel oil, rope tar and old fish, managed to be both thrilling and slightly nauseating, and we were grateful that he chose to head up the tiny Bull Hole channel, between Mull and the skerry of Eilean nam Ban, rather than straight out to sea. It extended our shelter from the strong westerly breeze for another ten minutes, and delayed any possible seasickness. That wouldn’t hit us till we passed the tiny white village of Kintra off our starboard bow, turned to port and reached the open sea.

That open sea was no stranger’s thing, even to us who saw it so rarely. It was a huge part of why we were here, the ‘ring of bright water’ that surrounded our island, and our own, vast, private swimming pool. Twice a day it covered the silver sands that we ran on and, when it retreated, its fading water revealed the mussels, shrimps and sea anemones that kept us engaged hour after salt-encrusted hour. We grazed ourselves on its rocks as we slipped on the thick carpets of its ochre blad-derwrack seaweed. It was the provider of mystery for us, as into it dived the vertical, laundry-white gannets, and out of it, if you were lucky, came mackerel and crabs to eat, otters to gaze upon and seals to swim with. The moods of the sea defined the day and the land we ran across. Journeys like the one we were on today supplemented the ferry crossings and the local fishing trips in my grandmother’s sky-blue rowing boat, and gave the sea another, wilder context. 9

I sat up in the prow of the boat while the two adults exchanged news of local infidelities, and my sister chatted away with the friend she had brought up to Mull for the holiday. I had a tiny notebook-diary with a stubby pencil tucked into its spine for making notes of what I saw, the trick being to identify whatever I could for myself before having to ask for Callum’s help. That was very definitely a last resort.

I have that little book still, the embryonic evidence that, even then, I was a captive to numbers. My looping, schoolboy hieroglyphics set out the order in which I saw different birds that late July Tuesday morning.

‘Day 4233 of my life,’ it begins, in which way it always began. Looking back at it, I suppose that, in a boyhood of only the most moderate achievements, just hanging around for nearly twelve years was a feat not to be underestimated. ‘Weather: OK.’

‘Great black-backed gull (lots); herring gull (ditto); arctic tern; oystercatcher; curlew; gannet (x4); cormorant (x2); heron; merganser (?); porpoise.’ Every so often, the line of the pencil would jerk in a strange direction, driven by the sharp movements of the boat as she turned half to port to head out to Staffa, meeting head-on the first of the open sea swell.

I had a life list of 82 birds at the time, mostly seen in and around my parents’ garden in Sussex, so these trips were always pregnant with the possibility of new additions. Such research as I was capable of here, namely a visiting birder from Holland whom I had met briefly in the Bunessan village stores the previous day, had suggested I might just get a black guillemot.

‘There sits black guillemots on the water for you, maybe,’ he had said mysteriously, as he bundled three cauliflowers and 10 a two-day-old Daily Mail into his shopping bag. ‘They were so for me two days since.’

Forty minutes later, we were nearing the dark and vertical mass of Staffa, its symmetrical bulk softening into its true natural irregularity as we approached. There were puffins, guillemots and razorbills bobbing around in the sea on the right side of the boat, which everyone else was watching from the starboard rail. I stayed on the other side watching gannets, and possibly just to make an adolescent point about not following the crowd or being predictable. Also, I knew that I would see things that the others wouldn’t, which was the important thing, my lists being as much about competition as they were the true records of sightings.

That was the precise moment I saw it for the first time.

I can still hear my grandmother’s voice in the background, telling Callum about something bad that had happened in Morocco earlier that week, a coup, and Callum, whose horizons in his latter years stretched genuinely no further than the sea around the Ross of Mull, saying enigmatically: ‘Aye. Well, that will be the way folk do things down there.’

At first I thought it might be a gull or a fulmar as it raced towards me, but no, it was flying through the air in the wrong way, and far too fast. It seemed to be more in the sea than above it, three quick wing beats, glide, three wing beats, glide, jinking this way and that and always with one wing tip seeming to touch the waves. As it drew closer, I saw the torpedo-shaped body, the thin, sickle wings, the white underside and the dark top. When it passed directly behind the boat the end feathers of its right wing appeared to brush the very wave itself, and I 11 knew for certain that I had never seen this bird before. I knew nothing of it, save that for a fleeting second, it had shone a beam of light into a world of wildness for me. I followed it round the stern of the boat, suddenly panicking that I would lose sight of it before I knew what it was, and miss the opportunity of a rarity.

‘Callum!’ I shouted, politeness thrown to the wind. ‘What’s that?’

‘That’s a shearwater,’ he said slowly, once he had turned around and watched it for a second or two. And then, after a pause, ‘She’ll be a Manx shearwater. Puffinus puffinus.’ He might not have known about coups in Morocco, but he knew the Latin name of every bird around the shores of his islands. ‘She’s a big wanderer, you know. One of the biggest of them all.’ Over the years I had come to realise that all Callum’s birds were ‘she’.

I came back to sit next to him by the tiller.

‘What do they …’ I couldn’t think of the right word, so I just picked the first one that came into my head. ‘What do they do?’

While he spoke, there were more shearwaters passing the back of his boat, heading back to some new fishery with a sense of purpose that seemed to elude the other seabirds.

‘What do they do?’ he repeated, pausing to see the effect of his words. ‘I suppose they just fly and fly till there’s no more ocean to fly over. These ones here will only be around for a few weeks and then … next stop: the South Atlantic.’

‘South Atlantic?!’ I parroted in my astonishment. ‘But that’s across the equator!’ It had never occurred to me that 12 birds crossed the equator, a line that to my young brain was still somehow a physical one, let alone traversed half the globe.

‘It is,’ he said quietly. ‘But I suppose that they don’t really go there, because I don’t think that they ever land there. They won’t land until they get back here’ – he nodded at the brooding bulk of Staffa – ‘next spring.’

And on he went. He had been in the Merchant Navy after the war, and had plied those same seas himself. He talked of albatrosses and shrieking winds that bent the mast almost in half; the lonely days when you could see nothing but the horizon, and the green flash of the setting sun; the deep aquamarine of the troubled sea, and the whiteness of the tips of the dreaded greybeard waves crashing into and over the stern of his boat. I could see in my grandmother’s eyes that his sea stories were losing nothing in the telling, but they spoke straight to the soul of a suggestible boy like me.

‘Ah, those greybeards,’ he said, his voice trailing off to some other time and place, like his pipe smoke wreathing into the sky above. ‘You’ll never forget your first one of those.’

And piece by piece, out there on a near-calm inland sea, he laid down for me the mosaic of the shearwater’s world. He was in his element, and so was I. Exaggerations they may well have been, but he knew how to fire a boy up.

‘That’s where your bird over there goes when she’s not here,’ he finished. ‘That’s why she’s always been my favourite. She’s the size and weight of a little woodpigeon, you know, but she’ll travel the world. I’m pleased to see the others, right enough, but she’s the one that makes my heart sing.’ 13

The prospect of this normally taciturn man’s heart singing was one that intrigued me. I squinted southwards into the noonday glare and saw another shearwater beating its way into the wind, and then another, and then no more.

‘Your bird.’ That’s what Callum had called it. My very own bird.

Little in my life dates back to an identifiable moment in time. Most of who I eventually became is the product of genetics and the thousand mundane developments that took place each hour of each day of my young life. So it is for all of us. But when that last shearwater beat its way across the wind, up towards its raft and then its night-time burrow among the wave-blasted, wind-sculpted revetements of Lunga, when the thoughts of Callum the Boat turned as they had from the workaday now to the heroic then, a switch had been thrown within me. From that moment on, the wilderness enticed me. No headland failed to summon me around it, no unclimbed hill allowed me to walk easily away, no pavement let me ignore what might lie beyond its last street-lit shadow. The wilderness now spoke to me of journeys without predictable endings, adventures deprived of certainty, like sentences without punctuation marks

That evening, I did what any eleven-year-old boy from the pre-internet age would have done, and scoured every shelf in my grandmother’s sitting room for information about those wanderers of the ocean. Normally, evenings at Loch Caol were for canasta, a card game for which she regularly created new rules that acted for her benefit. ‘Didn’t you remember that one?’ she would chuckle as she racked up the points towards 14 yet another inevitable victory. But on the shearwater evening, recognising a significant moment in my young life, she spent suppertime kindling the flame that had been lit in my mind, giving me the confidence to believe that what I was feeling was something to be treasured, not ridiculed.

‘It’s better than the Rolling Stones,’ she said in conclusion, as if that were reason enough to dedicate my life to them. ‘All that long hair and drugs, I don’t know!’

Deep down, I think she saw the shearwater as something that might draw me back to her island when teenage fancies might be beckoning me elsewhere. As I devoured the books that she found for me, whose grainy black-and-white images my mind’s eye can still just about make out, I came to understand, with the brash certainty that only a child can truly muster, that a tiny part of me had been branded by that first shearwater.

For introducing me to a wildness not controllable by humans, Bird Number 83 trumped all the others. All the sparrows, chaffinches, gulls and hooded crows that were part of Ardfenaig garden life were to a large extent predictable – not, as with the shearwater, birds that would emerge from, and recede back into, their wild ocean home. On reflection, there was nothing unusual in this: my grandmother’s trick was to let the wild glories of her world present themselves to you according to their own natural rhythm, and not to the dictates of any human plan.

If that shearwater happened to have spoken to me, it had done so very much on its own terms.

* A pelagic bird is one that spends all its life out at sea, other than when it comes to shore to breed.

2. DIOMEDES’ SECRET

October 1984, 53.1 Degrees South, 41.4 Degrees West

It seems to me that we all look at nature too much, and live with her too little. I discern great sanity in the Greek attitude. They never chattered about sunsets, or discussed whether the shadows on the lawn were really mauve or not. But they saw that the sea was for the swimmer, and the sand for the feet of the runner. They loved the trees for the shadows they cast, and the forest for its silence at noon.

Oscar Wilde

It was exactly how it should have been, a beautiful moment paid for entirely by the taxpayer.

I was a dozen or so years older than I had been on that day off Staffa, and once again in a boat. My potentially grateful nation had sent me down to the sub-Antarctic island of South 16 Georgia for five months in the wake of the Falklands War, to do my bit to keep it once more in British hands. One invasion was embarrassment enough for a lifetime, they told us as we sailed off from Port Stanley on RFA Sir Lancelot,* and, to ensure we saw off anyone else thinking of giving it a go, they gave us a cargo of more explosives and pyrotechnics than even our wildest young dreams had allowed for. In a military career where the most likely postings were to the dull north German plains or the unhappy streets of West Belfast, to be heading for the land of ice, of wilderness and of Ernest Shackleton was adventure writ large, and we knew it.

The journey out from England had taken twenty tedious days and had involved just about every form of transport yet developed by humanity, including plane, helicopter, coach, car, liner, launch and foot. A touch of complexity had been added by an unscheduled landing in Senegal on the way down to Ascension Island, which meant that we must have been the only Arctic warfare troops in the world taking anti-malaria tablets for six weeks among the icebergs. Seasickness was taking a fearful toll on my platoon on the last leg from Port Stanley to Grytviken, across the exposed sea-wastes of the Southern Ocean. Right now, most of the soldiers were lying below deck in varying states of physical anguish, still 200 miles west of our destination, and a source of sadistic pleasure to the ship’s crew in exactly inverse proportion to their own well-being.

17 ‘She rolls a bit, what with her flat bottom and all that,’ said the skipper rather too cheerfully for my liking, lighting his pipe and gazing out at the mountainous lines of swell rolling in from our starboard quarter. ‘So it’s nice that it’s calm for you lot.’ The sickly sweet smell of the pipe smoke, the after-effects of the nameless pie I had eaten for supper and the muffled sound of our medic vomiting into the abyss somewhere close by all conspired to defeat the last of my own stoicism, and I lumbered wordlessly from the bridge to stand outside at the rear of the ship, listen to the thrum of the twin diesel engines and breathe in the raw power of nature. Death, it occurred to me, was only marginally worse than what I was starting to go through, and I stared into the vacant greyness of the Scotia Sea wondering idly how cold, how bad it really would be if I slipped in, and who might nibble at me as I made my uncomplaining way to the bottom.

But once we were on the island, I thought to myself, we would be all right. Utterly on our own, joyfully on dry land, we would be some of the most remote soldiers on the planet. Thirty-three infantrymen with a small complement of cooks, engineers, medics and signallers to keep us fed, heated, healthy and in touch; young enough to feel invincible, but smart enough to understand that we probably weren’t. Ice warriors, fantasists, poets, body-builders and wildlife observers, we would be living the soldier’s ultimate dream of being 950 miles away from the next link up in the chain of command. Every six weeks or so a ship would call in to see how we were getting on and check that we were doing the important stuff, like cleaning our rifles and shaving; the intervals between visits would be punctuated by a 18 low fortnightly fly-by from an RAF C130, whose crew would unceremoniously lob out of its rear cargo door a vast waterproof bag containing fresh food, instructions and mail, which we would duly retrieve by inflatable boat from among the icebergs in our bay. Otherwise, we would spend our time climbing on glaciers, reading books and looking as fierce as our youthful complexions allowed, the better to deter any lurking invaders.

As for the neighbourhood we were moving into, our fellow residents would simply be the five million or so penguins on the island, half a million or more elephant seals and all the assorted seabirds that had not yet evolved a reason to fear the presence of humans. It was certainly going to be a long way from the flat, corvid world of Salisbury Plain, from where we had set off three weeks before. For a young man partly raised on the cry and the folklore of the seabird, it was a wonderful thing to be asked to go and do, an enthusiasm I had hidden as well as I could during the tearful goodbyes at home.

Birds had drifted in and out of my life over the last dozen years since that afternoon off Staffa, normally ‘in’ while I was on Mull or on the coast, and ‘out’ while I was anywhere else. Watching birds also tended to be something I fell back on when I was down and then ignored when I was cheerful, which I was most of the time. Every now and again, I would drag my tangled teenage confusions along with me on some long-distance footpath, watching choughs churning and spilling over the cliff edges, all the while wondering self-indulgently whether I should eventually be a soldier, poet, tycoon or armchair anarchist. Thus, depending on whether it was Byron or Bonaparte who had turned up on the day, did I watch birds from a standpoint 19 of either romantic idealism or detached superiority, before heading to a local pub and pretending, as I downed my beer, that I hadn’t been privately educated. Teenage can be complicated like that.

Crucially, birding was also what I shared with my father, who had an accountant’s fastidiousness about his claims and his note-keeping. When communication was fractious between us, which it quite often was in those years on the cusp of my adulthood, he would use the offer of a bird trip to allow calm to seep back into our relationship. After all, it’s hard to argue about life if you are both lying on the ground trying to work out if that thing browsing by those rocks is a Temminck’s or a little stint.

I kept a list of the birds that I had seen from on board the MV Keren,† the boat that took us from Ascension Island to Port Stanley, and the first lengthy sea journey I had ever made. Bird Number 83 is on it, as are great and sooty shearwaters, enormous cousins of the Manx, the latter of which ranges into every ocean on earth. But there had been no gasp of recognition, no thrill of reunion, just a routine and dutiful logging of a fact into a misused military notebook on the back of a commandeered liner. My role was to protect the outer reaches of 20 what was left of my nation’s empire, not to return to a childish enthusiasm.

A week later, on the ship from Stanley to South Georgia, it took a single moment in time to change me back for ever.

As the minutes passed out there on the deck and my core temperature plummeted, I started to regain some sense of equilibrium, and by way of diversion re-read my share of the mail that had been delivered to us at Port Stanley two evenings before. The final one of these was from my grandmother, typed and corrected by her rheumatic Hebridean hands on an old Smith Corona typewriter, back there in her whitewashed croft on the Ross of Mull. I always read hers last.

‘Not much going on here. Ian the Park has been drunk for a week, and I am therefore beginning to wonder if I shall ever get my raspberry cage mended in time for next year’s crop. A young couple rolled their car off the cliff road at Gribun and Annie M at Kintra said that “when they woke up in the morning, they were all cold”. Other than that, just the normal infidelities and howling winds.’

The letter finished with an uncharacteristic intercession for my personal safety.

‘I will pray nightly to St Jude (the patron saint of lost causes) that you don’t fall down too many crevasses while you’re on your mission. However, if you do, I am told that some previous record of prayer on your own part would be quite useful, too, plus the more tangible help of crampons. 21

‘And think of it not as work but as a privileged adventure. Keep safe, don’t complain and, above all, have fun. I will send you some whisky for Christmas if your generals don’t find it first.’

Then there was a postscript to say that she had included in the envelope a 1917 George V penny that she had found in her coin drawer, to remind me of the year that Ernest Shackleton had made the first crossing of the island. ‘Keep it in your pocket,’ she had added, ‘and it might just make you more adventurous, too, and keep you safe.’ In a way, it did both, as four months later a group of us retraced the explorer’s epic crossing of the island at the end of his escape from the Antarctic ice.

While finishing the letter, I had developed a vague sense that I was being watched and, for a second, couldn’t think by whom, or from where. It was only when I folded the letter back into its envelope and looked southwards over the starboard rail into the vast grey acreage of emptiness beyond that I noticed a shadow in the corner of my left eye. I turned to look more closely at it.

I knew enough about seabirds to understand without any hesitation that it was a wandering albatross, my first. Most seabirds are predominantly white, especially below, but there is a glowing purity of whiteness about the wanderer that makes identification simple, even from a distance. It had taken a long time, a dozen years, for his flight to intersect with mine.

Given the folkloric expectation of a ‘first albatross’ to change the life of even the most part-time birder, I was initially calm. It was a major tick on the life list for sure, like one of 22 the big five in an African game reserve, but no more than that. Almost an anti-climax. A large seagull, in fact.

But then it started to dawn on me that the bird I was looking at was still two football pitches’ distance away from me, working his‡