Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titania Medien

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

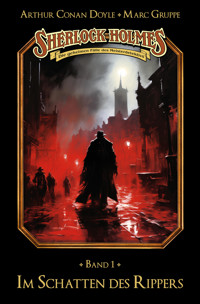

London 1888: A brutal serial killer is terrorising the population of London’s East End. The police are unable to prevent his crimes, which increase in cruelty and perversity from murder to murder. Who is this unknown killer, who strikes on busy streets without leaving a trace? A very personal motive prompts consulting detective Sherlock Holmes to make his own investigations. Can he succeed in stopping the gruesome series of murders?

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 135

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Arthur Conan Doyle

Marc Gruppe

Shadow of the Ripper

Imprint

Copyright © 2025 Titania Medien GmbH

Elberfelder Straße 47, 40724 Hilden, Germany

Based on an audio dramatisation by Marc Gruppe

Book editor: Stephan Bosenius

Copy editors: Silke Horvath/Dr. Daniela Stöger

Translation: Dr Kornel Kossuth

Illustration: Bastien Ephonsus

Layout: Lars Auhage

Sherlock Holmes logo and frame: Firuz Askin

Bibliographic information of the German National Library

The German National Library lists this publication in the German National Library; detailed bibliographic data is available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de.

This work, including all content, is protected by copyright. All rights reserved. Reprinting or reproduction (including excerpts) in any form (print, photocopy or other method) as well as storage, processing, duplication, transmission and distribution using electronic systems of any kind or by any other means, in whole or in part, is prohibited without the prior express permission in writing of the publisher. All translation rights reserved. We explicitly reserve the right to use our works for text- and data-mining in accordance with Section 44b of the German Copyright Act (UrhG).

This work is based on true events, but is nonetheless fiction. Any similarities between non-historical characters and situations and living or dead persons are unintentional and purely coincidental.

978-3-69027-001-4

www.titania-medien.de

Find Titania Medien on Facebook, Instagram and YouTube.

Notice:

Depending on the reading device used, the text released by the publisher may be displayed differently.

The publisher is not responsible for any content accessed through links contained in the text, which are solely the responsibility of the respective service provider. The publisher has carefully checked any externally linked pages at the time of publication, and no legal violations were recognizable at the time of linking. Later changes are beyond the sphere of the publisher for which reason the publisher cannot be held liable.

This e-book meets the requirements of the W3C standard EPUB Accessibility 1.1 and the WCAG rules contained therein, level AA (high level of accessibility). The publication is designed to be accessible through features such as a Table of Contents, Landmarks (navigation points) and its semantic structure. If the e-book contains images, these are accessible via image descriptions.

Inhalt

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Epilogue

Preview

Chapter 1

My name is Dr John Hamish Watson. Although I am nothing more than a simple military doctor, my name is now known all over the world.

I owe this solely to one circumstance in my life – and it has nothing whatsoever to do with my actual profession. For many years I enjoyed the privilege of accompanying the investigative work of my friend Sherlock Holmes as a chronicler. It was always a pleasure to amaze my readers with the details of the master detective’s adventures.

Occasionally, however, there were cases whose reports were initially expressly not intended for publication for a variety of reasons. This was usually due to the client’s wish for discretion or simply because of the explosive nature of the events described. These reports were sealed and stored in an archive until the time would finally come to relate these secret cases of the master detective.

The case in which Holmes had to deal with what was certainly the most brutal criminal of his career preoccupies me to this day, and is still the subject of weekly press reports at home and abroad.

The year was 1888.

Just over a year earlier, Queen Victoria had celebrated her Golden Jubilee.

Back then, London gave the impression of consisting of two cities. On the one hand, it seemed to be flourishing in the shadow of the opulent and lavish splendour of the aristocracy, while on the other hand, there was the deepest and most oppressive poverty. The construction of the new Shaftesbury Avenue, like the extension of the railway line, had taken a huge toll on the inhabitants, as large areas that had previously provided housing for people on low incomes had been demolished. As a result, many wage-earners and unemployed people suddenly had no roof over their heads. Night after night, along with many others who had suffered a similar fate, they struggled to find a place to sleep in the notorious East End neighbourhoods, of which Whitechapel had a particularly bad reputation.

Almost eighty thousand people lived in this fairly small neighbourhood, which consisted mainly of warehouses, factories, tenements, slaughterhouses, public houses and dubious hostels.

Losers of the industrial boom, barely integrated immigrants from a wide range of social backgrounds, mixed their religion, culture and language into this urban melting-pot. Most tenements were not built to last and within a short space of time many of them were infested with vermin; mould proliferated in the crumbling walls. Large families lived in filthy rooms no larger than a few square feet. In Whitechapel there were over two hundred hostels where you could spend the night in a stuffy, overcrowded dormitory for four pence or in a rotten double bed for eight pence. Otherwise, your only hope at night was to find a sheltered place outside or to take refuge in one of the completely overcrowded poorhouses.

Having not been there for quite some time, my path led me once again to St Bartholomew’s Hospital because I had asked a colleague there for advice about one of my patients.

While I was waiting for him, I noticed how many people were in the emergency department hoping for treatment and, above all, how high the number was of those who were sent away again, although even a layman could have recognized that they were seriously ill.

When I asked indignantly why this was so, my colleague told me that this was normal procedure. »Take a look around the slums of London, Dr Watson. In the murky gaslight drunks regularly fail to spot the potholes in the pavements and cobbled streets and injure themselves when they fall. Others end up in the stinking gutter and infect themselves with pathogens in the murky broth. And that’s not all! Just look at the freshly washed clothes on the washing lines – they are black with soot and stink of the fumes from coal-fires. The people here breathe in these fumes around the clock. The countless prostitutes are carriers of sexually transmitted diseases, and in many emergency shelters hundreds of people from God knows where all sleep in one room. You can imagine how quickly epidemics, infections and venereal diseases spread. Unfortunately, we don’t have the financial resources, let alone enough beds, to treat all the homeless people, prostitutes, alcoholics, good-for-nothings and criminals. Many spend the night on the street simply because they don’t want to give up alcohol, but that is a precondition for admission to the poorhouse.«

»But these people will die an early death if they don’t receive adequate medical care!« I shouted, shocked.

»So what?« my colleague said with a shrug and somewhat too callously for my taste. »Sooner or later they’ll die anyway. Give them medication and eight times out of ten they’ll immediately sell it on for a bottle of gin.«

Completely beside myself at such an attitude, which in my eyes was not only reprehensible but also hardly compatible with the Hippocratic Oath we doctors swear, I left the hospital and told my wife at home about the shocking things I had seen and heard.

»I’ve come to a decision, and it’s not been easy, but I have no other choice. I have to do something, Mary. I can’t stand idly by and watch people die by the dozen just because they’re poor. And that in London! It’s my duty as a doctor to do something about it. As best I can.«

»Your compassion does you great credit, John, but if even the great St Bartholomew’s Hospital can’t do much, I don’t think you as an individual will be able to turn the tide.«

Deep in my heart, I realised she was right. Despair, anger and an unpleasant feeling of powerlessness filled me. Mary and I hadn’t been married very long back then. I loved my wife dearly and was sure that she felt the same way about me. However, soon after our marriage, storm clouds had appeared on the horizon because my friend Sherlock Holmes had completely withdrawn and was no longer investigating. Apparently, he was planning to devote himself exclusively to his violin to recover from our joint case »A Scandal in Bohemia«. It was clear to me that he was lovesick after Irene Adler’s abrupt departure, which he himself vehemently denied. Although I enjoyed my newfound marital bliss and the time in my own practice very much and had no cause for complaint about a lack of work, I increasingly began to miss the intellectual discussions and the thrill of investigating with the master detective. This all the more as treating the various petty ailments of my upper middle-class patients unfortunately left me with no sense of fulfilment. Helping poor people who had to fight for a place to sleep and fear for their lives night after night in the worst hygienic conditions seemed to me, in contrast, a far more meaningful task than going to an exclusive club or an elegant reception every evening to make superficial smalltalk.

Mary couldn’t quite understand my change of heart and reacted unexpectedly hurt and with bewilderment when I told her that I intended to move to Whitechapel for a while to provide gratis medical care to sick people there.

To be honest, I myself wasn’t entirely convinced of my plans at the time. I was painfully aware that it was bold, if not foolhardy, of me to want to settle in a neighbourhood that even the police officers who were on duty there day in day out blanched at.

A woman named Martha Tabram had just been gruesomely murdered in George Yard; her body had been found stabbed to death at the foot of a staircase. It was whispered that the perpetrator was still at large.

In this light Mary’s horror and disapproval of my plans were quite justified. At the same time, my mission so enthused me that there was no turning back for me. Amidst my wife’s verbose protests, tears, insults and threats, I organised my move, somewhat defiantly, to an environment that was more miserable and brutal than I could ever have imagined. It was only when I moved into my little room in Goulston Street that I truly realised how privileged my life had been up to that point.

The street in which my new home was located was flanked by the so-called Wentworth Dwellings: long, unadorned apartment blocks reminiscent of factory buildings or barracks. Apart from me, the building complex was almost exclusively inhabited by Jews who more or less earned their living from tailoring or other handiwork.

The mistrust of the inhabitants of this slum towards me was immense.

Instead of gratitude, as I would have expected, their rejection and almost hostile attitude brought me down to earth very promptly when first I approached potential patients on the street. At the same time, I heard about many shocking and tragic fates.

Mary Ann Nichols, known as Polly, had left her husband, her five children and her financially secure life and had subsequently become homeless – partly due to alcoholism. I bumped into Polly by chance on 31st August on my way to the Frying Pan pub on the corner of Thrawl Street in Spitalfields. Once again, as I quickly realised, she was about to spend the money for an overnight stay in Wilmott’s Lodging House, which was at least relatively clean and only allowed women in, on alcohol. She was wearing a conspicuous black velvet cap and was ranting about a lodging house called the White House, which housed both men and women and to which she therefore had no intention of returning. I was quite amazed at the remaining dignity of this woman, who was aware that she would have to sleep on the street after a night of drinking, but at the same time was not prepared to compromise her ideas of morality. I met her a second time just before half past two in the morning when I went back out to check on casualties from a fire in the dry dock at Shadwell. She was leaning against a greasy wall in Osborn Street with her friend, a certain Ellen Holland, and could hardly keep on her feet, she was so drunk.

»Three times I’ve had enough money for a place to sleep, and each time I’ve spent it again, Doctor!« she called out to me, giggling.

How she had earned the money remained her secret. I didn’t ask, but continued my nocturnal walk, which took me through Buck’s Row. Lost in thought, I strolled past a row of small workers’ houses and passed an elongated façade with a large entrance gate.

What I didn’t realise at the time was that I had just seen Polly Nichols for the last time, and was passing the very spot that would soon become a bloody crime scene.

On the first of September a man who was surprisingly well dressed for the area knocked on my door. He was wearing a slightly worn black frock coat, identically coloured trousers that had seen better days, a matching tie and a shabby top hat. I immediately noticed that the man was quite agitated, as he was unable to look me in the eye for any length of time.

Admittedly, this unexpected visit from a complete stranger irritated me.

So I asked: »Is there anything I can do for you?«

He got straight to the point. »You’re the doctor who helps the needy here free of charge?« I said yes.

»You know a Mary Ann Nichols, called Polly, I’ve heard.« When I nodded, he continued: »My name is William Nichols. I’m Polly’s husband, but we’ve been separated for some time. The police have asked me to look at a dead body in the morgue because they say it’s Polly. They want me ... to identify her.«

»For heaven’s sake!« I exclaimed in shock. »This can only be a mistake! I saw Polly last night: she was alive and kicking then.«

»To be honest, I’m afraid to go there alone. I’ve never seen a dead body before. And if that really is Polly lying there, I’m sure I’ll faint on sight. I used to love her very much, you know.«

»I’m sure you did,« I replied sympathetically.

»That’s why I wanted to ask you if you would accompany me as a doctor. And since you also know her ...« he faltered and quickly corrected himself, »... knew her, I would be grateful if you could stand by me.«

Naturally, I agreed to accompany William Nichols on his difficult errand and dressed quickly for the occasion. As it had recently started to drizzle, I also reached for my umbrella.

Filled with the vague hope that the dead woman would be one of the countless other fallen women in the area, I walked alongside the poor man, who was visibly trembling inside and out; once he had started a family with Polly and had looked forward to a rosy future with her.

Lost in sombre thoughts, we reached the morgue. The inspector on duty, Frederick Abberline by name, was a man in his mid-forties with thinning hair and friendly eyes. After a curt greeting, he led us through the back door into a courtyard, at the side of which we saw a simple brick shed. After entering, we both took off our hats almost simultaneously, following a spontaneous impulse.

In the centre of the room stood a plain pinewood coffin. When the lid was opened with an unpleasant crunch, the pale man next to me immediately began to whimper.

I, too, recognised Polly Nichols immediately. Her carotid arteries had been severed and her naked corpse showed a number of cuts to her abdomen.

The inspector told us in a toneless voice that she had been found lifeless in Buck’s Row that morning. I couldn’t believe what I was hearing: Polly had been found lying next to the gate I had passed the night before!

»I forgive you,« whispered the dead woman’s husband next to me, shaken to the core. »I forgive you for everything you’ve done to me and the children.«

It took a while before Inspector Abberline was able to escort the widower out. I put him in a hansom cab to take him home to Coburg Road.

Five children had lost their mother. The couple’s sixth child had been buried many years before.

I couldn’t help but think of Sherlock Holmes. Should I go to him about the heinous murder of this unfortunate woman and ask him to find out who did it?