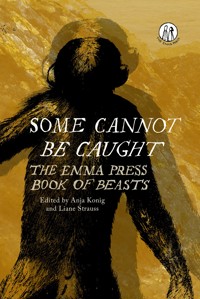

Some Cannot Be Caught E-Book

Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The Emma Press

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Serie: The Emma Press Poetry Anthologies

- Sprache: Englisch

The Emma Press Book of Beasts rustles and roars with the voices of animals and humans, co-existing on Earth with varying degrees of harmony. A scorpion appears in a shower; a deer jumps in front of a car. A swarm of snowfleas seethes through leaf litter; children bait a gorilla at the zoo. The poems in this anthology examine hierarchy, herds, power, and the price we pay for belonging.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 46

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

SOMECANNOTBECAUGHT

THEEMMAPRESSBOOKOFBEASTS

OTHERTITLESFROMTHEEMMAPRESS

POETRYANTHOLOGIES

The Emma Press Anthology of the Sea

This Is Not Your Final Form: Poems about Birmingham

The Emma Press Anthology of Aunts

The Emma Press Anthology of Love

BOOKSFORCHILDREN

Moon Juice, by Kate Wakeling

The Noisy Classroom, by Ieva Flamingo

The Queen of Seagulls, by Rūta Briede

The Book of Clouds, by Juris Kronbergs

PROSEPAMPHLETS

Postcard Stories, by Jan Carson

First fox, by Leanne Radojkovich

The Secret Box, by Daina Tabūna

Me and My Cameras, by Malachi O’Doherty

POETRYPAMPHLETS

Dragonish, by Emma Simon

Pisanki, by Zosia Kuczyńska

Who Seemed Alive & Altogether Real, by Padraig Regan

Paisley, by Rakhshan Rizwan

THEEMMAPRESSPICKS

The Dragon and The Bomb, by Andrew Wynn Owen

Meat Songs, by Jack Nicholls

Birmingham Jazz Incarnation, by Simon Turner

Bezdelki, by Carol Rumens

THEEMMAPRESS

First published in Great Britain in 2018 by the Emma Press Ltd

Poems copyright © individual copyright holders 2018

Selection copyright © Anja Konig and Liane Strauss 2018

All illustrations created by Emma Wright from images found on Early English Books Online (EEBO).

All rights reserved.

The right of Anja Konig and Liane Strauss to be identified as the editors of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

ISBN 978-1-910139-88-2

A CIP catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library.

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ International, Padstow.

The Emma Press

theemmapress.com

Jewellery Quarter, Birmingham, UK

EDITORS’ INTRODUCTION

Anja: Humans are animals. I have long found this a clarifying thought. There is much we have in common, most importantly the desire to belong to the herd, which is the hallmark of any social species. As with other social animals, we pay a price for this belonging: our obsession with hierarchy, with knowing who is top dog; power structures, pecking orders. The human animal is capable of competition and collaboration, aggression and love.

Liane: And of course, humans are not the only animals who form friendships, are capable of selflessness and can act out of the desire to help others. Recent research confirms that ‘monkeys, apes, dogs, and a growing list of other mammals, can recognize and protest unfair conditions’. Not only this, but: ‘Animals employ various forms of punishment… [that bear a] striking resemblance to our most effective modes of rehabilitative and restorative justice.’1

You might say science is finally catching up to what poets at least as far back as Aesop have always known, that the boundary lines humans like to draw between other animals and themselves are far more elastic, and porous, than they think.

Anja: The anthology explores these fluid lines of separation between us and other animals, speaking about empathy for others of our own kind as well as animals of different species. A beautiful example is Maggie Sawkins’ ‘Frilled Lizard’:

he may be cold to the touch

but inside

he’s alight

Liane: You can see those lines dissolving in Maggie Dietz’s ‘Late spring’, where ‘the boy’ sitting in his bath identifies with ‘the vanished bird’ and sees them both, merged, in the mock-heroic simile: ‘The soft pink belly like a clam.’

Anja: But the book also speaks of the limits of empathy, of cruelty and indifference, of predators and prey, like Russell Jones’s ‘The Alligator Get-Out Clause’:

When it moves, don’t resist –

the alligator has spent millennia perfecting its bite.

Liane: Speaking of jaws and clauses, quite a few of the poems sink their teeth into the question of language, whether it really is one of the things that separates humans from other beasts.

Anja: Yes, that’s a common theme in the anthology. Did you notice how in Pascale Petit’s ‘My Wolverine’, for instance, ‘words are born/ fighting’?

Liane: I sure did! There’s also a telephone receiver in that poem that acts like a muzzle. And I felt my own blood run cold when the response to the words ‘barked’ in Saliann St-Clair’s ‘You smell like apples’ evolves from an instinctive repulse to deliberate violence.

Anja: So the poems examine how we as humans are similar to animals and how we are, or think we are, different from them. The poems speak to what is shared – joy, fear, aggression, sex.

Liane: Yes, and humour. Don’t forget humour. My favourite rhyme in the book is the one Nancy Campbell comes up with for the new mammal whose discovery she celebrates, very much à la Dorothy Parker, in ‘The Omnivore’.

Anja: The most intense pleasure for the editor of an anthology is the dialogue with other poets, the thrill of reading submissions and finding the poem that jolts you, that addresses you, that shows you how it’s done.

Liane: Absolutely. I was dazzled by the economy with which Stav Poleg collapses the putative boundary between civilisation and nature in the opening image of ‘Boy’:

The most unlikely fish,

swimming upright like a streetlamp

in an ocean.

Anja: It was electrifying to read Sarah Hesketh’s ‘Martha, The Last Passenger Pigeon’, a topic that has long fascinated me; she wrote the poem I wanted to write, wrote it perfectly and wrote it in a way that I never would have in a million years: Martha, the endling of her species, as a good-time girl:

Lipstick fires in her feathers; the smoky

turn of her neck as she came into a room.

Who knew where she was going to, and

what’s a girl like that got to do with settling down?