Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Pushkin Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

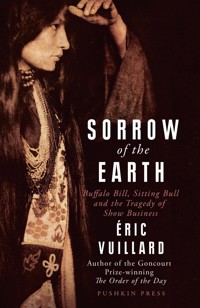

And now the show is starting. An Indian enters the arena; it's the victor of the Battle of the Little Big Horn. He's wearing his finest costume. "Ladies and gentleman, let me introduce the great Indian chief..." vociferates Frank Richmond from his rostrum. Sitting Bull has probably never been as alone as he is at this moment, in the midst of the American flags and the great entertainment machine...Buffalo Bill was the prince of show business. His spectacular Wild West shows were performed to packed houses across the world, holding audiences spellbound with their grand re-enactments of tales from the American frontier. For Bill gave the crowds something they'd never seen before: real-life Indians.This astonishing work of historical re-imagining tells the little-known story of the Native Americans swallowed up by Buffalo Bill's great entertainment machine. Of chief Sitting Bull, paraded in theatres to boos and catcalls for fifty dollars a week. Of a baby Lakota girl, found under her mother's frozen body, adopted and displayed on the stage. Of the last few survivors of Wounded Knee, hired to act out the horrific massacre of their tribe as entertainment. And of Buffalo Bill Cody himself, hamming it to the last, even as it consumed him.Told with beauty, compassion and anger, Sorrow of the Earth shows us tragedy turned into a circus act, history into sham, truth into a spectacle more powerful than reality itself. Could any of us turn away?

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 117

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

ÉRIC VUILLARD

Sorrow of the Earth

Buffalo Bill, Sitting Bull and the Tragedy of Show Business

Translated from the French by Ann Jefferson

PUSHKIN PRESS LONDON

to Stéphane Tiné and Pierre Bravo Gala

CONTENTS

The Museum of Mankind

SPECTACLE IS THE ORIGIN OF THE WORLD. Tragedy stands before us, motionless and strangely anachronistic. And so, in Chicago, at the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893 commemorating the 400th anniversary of Columbus’s voyage, a display of relics on a stall in the central aisle included the desiccated corpse of a newborn Indian baby. There were twenty-one million visitors. They promenaded on the wooden balconies of the Idaho Building, admired the miracles of technology, like the gigantic chocolate Venus de Milo at the entrance to the agricultural pavilion, and then bought cones of sausages for ten cents apiece. Huge numbers of buildings had been erected, and the place resembled a gimcrack St Petersburg, with its arches, its obelisks, its plaster architecture borrowed from every age and every land. The black-and-white photographs we have convey the illusion of an extraordinary city, with palaces fringed by statues and fountains, and ornamental pools down to which stone steps slowly descend. Yet it’s all fake.

But the highlight of the Columbian Exposition, its apotheosis, the feature that was to attract the greatest number of spectators, was the Wild West Show. Everyone wanted to see it. And Charles Bristol—the proprietor of the stall with the Indian relics and the exhibit of the baby’s corpse—also wanted to drop everything and go! He already knew the spectacle, because right at the start of his career, he had been the manager and wardrobe master for the Wild West Show. But it was no longer the same, and it had now become a colossal enterprise. There were two performances a day, and eighteen thousand seats. Horses galloped past a backdrop of gigantic painted canvases. It wasn’t the loose string of rodeos and sharpshooters that he had known, but a veritable enactment of History. So while the Columbian Exposition was celebrating the industrial revolution, Buffalo Bill was glorifying conquest.

Later on, much later on, Charles Bristol had worked for the Kickapoo Indian Medicine Company, which employed nearly eight hundred Indians and around fifty Whites to sell its stuff. Its flagship medicine was Sagwa, a mixture of herbs and alcohol for the treatment of rheumatism and dyspepsia. And it would appear that cowboys suffered particularly from wind and borborygmic dyspepsia, because right across the country people were in search of a remedy. Eventually, Charles Bristol abandoned the sale of medicines and embarked on a series of long tours with his collection of objets d’art. Two Winnebago Indians who were part of the Medicine Company had decided to follow him. The museum toured in the Midwest and the little sketches it staged, where the Indians performed dances to illustrate the specific function of each object, were both entertaining and educational.

Towards the end of 1890, barely three years before the Columbian Exposition, Charles Bristol had joined forces with a bum by the name of Riley Miller. Once Bristol chummed up with Riley, the story becomes hard to credit. Previously, according to him, Bristol had accumulated his treasures thanks to his Indian friendships—a long succession of little gifts. But Riley Miller was a murderer and a thief. He would scalp and strip dead Indians: he murdered them and then took their moccasins, their weapons, their shirts, their hair—everything. Men, women or children. A part of the relics displayed by Bristol at the Chicago Fair came from these activities. Later on, the history museum in Nebraska bought Charles Bristol’s collection; and today, somewhere in the museum’s reserve collection, you might well come across the desiccated body of the Indian baby from the Exposition. What this tells us is that show business and the human sciences had their origins in the same displays, with curiosities lifted from the dead. Which means that today, what you find on museum shelves throughout the world is nothing but trophies and plunder. And all the African, Indian or Asian objects that we admire were stolen off corpses.

What Is the Essence of Spectacle?

LET US GO BACK A LITTLE, to a time a few years before the Chicago Columbian Exposition, and take a closer look at the tremendous Wild West Show. What force of attraction can bring forty thousand people a day to see this spectacle? Down what incline in their fleeting lives do they slide to reach the great arena where yelling horsemen gallop through cardboard scenery? It was ten years before the Great Exposition that Buffalo Bill set up his show; the thing was nonetheless put together gradually, incorporating new acts, piecemeal fashion, one after the other. The early version was most likely nothing more than a tedious succession of rodeos, but Buffalo Bill didn’t stop there. When the former scout took to the stage, he was determined to revolutionize the art of entertainment and make it into somethingdifferent. So Buffalo Bill dragged his circus from town to town, improving the acts and recruiting new stars; but as it developed, the Wild West Show acquired a new form of success; it was no longer just a circus, no longer a troupe of acrobats performing on stage. No, it was something quite new. And yet, when you looked carefully, it was all rather ramshackle, just a string of little numbers; and there was nothing very extraordinary about it, no monsters, no hideous creatures; so what was it, then?

Movement and action. Reality itself. Yes, just galloping horses, re-enacted battles, suspense, people falling down dead and getting up again. It had everything. And the audiences grew all the time, clapping, laughing, shouting, enthralled, completely spellbound; as if the world had been created in a drum roll.

However, the real spark was elsewhere. The central idea of the Wild West Show lay somewhere else. The aim was to astound the public with an intimation of suffering and death which would never lose its grip on them. They had to be drawn out of themselves, like little silver fish in a landing net. They had to be presented with human figures who shriek and collapse in a pool of blood. There had to be consternation and terror, hope, and a sort of clarity, an extreme truth cast across the whole of life. Yes, people had to shudder—a spectacle must send a shiver through everything we know, it must catapult us ahead of ourselves, it must strip us of our certainties and sear us. Yes, a spectacle sears us, despite what its detractors say. A spectacle steals from us, and lies to us, and intoxicates us, and gives us the world in every shape and form. And sometimes, the stage seems to exist more than the world, it is more present than our own lives, more moving and more persuasive than reality, more terrifying than our nightmares.

And in order to bring in an audience, in order to get ever more people wanting to come and see the Wild West Show, they had to be told a story, the story that millions of Americans, and then millions of Europeans, wanted to hear, the only story they wanted to hear, and the one that, perhaps without knowing it, they were already hearing in the crackle of the electric light bulbs. The inhabitants of American cities, this new breed of humans whose disquiet is a stubborn question addressed only to them, and to no one else, who in the depths of their angst have a sense of being set apart, designated by the spirit of progress to seize the torch of humanity and hold it higher than anyone has ever held it before, let me tell you, these inhabitants of the cities of America wanted to witness something different, they wanted to travel across the Great Plains in their imagination, to ride through the canyons of Colorado and experience the lives of the pioneers. It might appear strange, but by means of the lives of the pioneers and the turbulent tales of their migration, the inhabitants of the young American cities wanted to be present at a live broadcast of their own History, that great display of courage and violence which, a few thousand miles away, was still in the making.

All this was very splendid, but in reality, thanks to a fetid emanation from the crowd or an effluence from the soul, Buffalo Bill knew that it wasn’t the cowpokes or the sharpshooters that the crowds came to see. No. The power of his spectacle (and he probably didn’t really know where it came from), the idea that gave it its authentic substance, the thing that made it irresistible was the presence of the Indians, real Indians. Yes, that was the only thing that people came for. Oh! of course they didn’t realize this themselves, because most of them despised Indians. But if they scrimped and saved to buy tickets for every member of the family, and took their seats quietly in a row on the bleachers, it was unquestionably to see the Indians and not for any other reason. So Buffalo Bill had to show Indians. And for such a spectacle to prosper, he had to keep coming up with new stars.

For this, apart from Buffalo Bill himself, there was Major John Burke, his impresario. Like most of the people who wore cuffs in those days, John Burke wasn’t a major at all. You come across him sometimes under the name of Arizona John, although he had never been to Arizona either. He was just a swindler of the worst kind. In those days, any nincompoop could found a city, become a general, a businessman, a governor or President of the United States; and perhaps this is still the case. John Burke had sensed the coming of the vast machinery of a culture of spectacle, and was now press officer to Buffalo Bill—his publicity agent. He was the greatest and the wackiest publicity agent. Thanks to a perfect match between the man and his times, the former journalist, broker and one-time leader of a troupe of acrobats became the inventor of show business.

An Actor

CIVILIZATION IS A HUGE and insatiable beast. It feeds on everything. It needs pepper, and tea, and coal, and tin. It is impossible ever to satisfy. Civilization also demands less material sustenance, but it quickly wearies of its fare. It constantly requires new recruits, new faces. And so the Wild West Show had regularly to hire more actors. And for this, there is something better than artistes, better than the best acrobats, better than any freak of nature. There are the real protagonists of History. Just think about it! You can always pay a juggler to astound an audience, you can always dig out a hunchback or a pair of Siamese twins to draw a curious crowd. But getting tens of thousands of people to come every day, to make fifteen thousand, twenty thousand people pay over a dollar, morning and evening for years on end, requires something more than jugglers and hunchbacks. It requires something quite unprecedented. And this was why, one morning in 1885, after several years of exile and imprisonment, the old Indian chief Sitting Bull, victor at the Battle of the Little Big Horn, received a visit from John Burke.

The big beast had come alone. The weather was glorious. As he perched on his sprung phaeton, between two jolts of his vehicle, John Burke had carefully pondered his plan. It’s true that the road bucked a little too much for a man of his girth, the potholes and the humpback bridges had caused him a fair degree of misery. He had driven grumbling alongside a never-ending avenue of willows, then taken a narrow track that cut across a boundless plain. But although he was much tried by his journey, once he arrived, his manner was relaxed and affable. Yes, he’d come with a mouth full of pieties, a few small presents and a clear blue sky. He offered a cigar to the Indian, who refused it. He smoked his nabob’s peace pipe by himself, before the silent Indian. After the usual exchange of greetings, during which a sly and ferocious battle was instantly engaged, John Burke launched into a long, convoluted, labyrinthine and meandering speech. Between two compliments he rearranged his hair, pushing it back and clamping it round his ears. But the old Indian maintained an obstinate silence. And after a quarter of an hour of chatter, John Burke realized that his hedging about was getting him nowhere; Sitting Bull seemed cagey, and he would do better to get to the point.