St. Valery E-Book

Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Birlinn

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

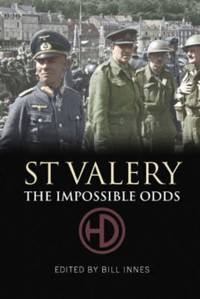

The gallant rearguard action which led to the capture of the 51st Highland Division at St Valéry-en-Caux (two weeks after the famous evacuation of the main British army from Dunkirk) may have burned itself into the consciousness of an older generation of Scots but has never been given the wider recognition it deserves. This new book re-examines that fateful chain of events in 1940 and reassesses some of the myths that have grown up in the intervening years. Two of the main contributors to this collection of soldiers' reminiscences, Angus Campbell from Lewis and Donald John MacDonald from South Uist, were both traditional Gaelic bards. Their work has been translated from their native language and reflects both the richness of the vocabulary they had acquired through the Gaelic oral tradition and their individual gifts as natural story-tellers born out of that tradition. These vivid accounts bring alive the chaos and horror of war and the grim deprivation of the camps and forced marches which so many endured. Yet the personal stories also resound with the spirit, humour and sense of comradeship which enabled men to fight on in desperate situations and refuse to be cowed by their captors.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 488

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

This eBook edition published in 2012 byBirlinn Limited West Newington House Newington Road Edinburgh EH9 1QSwww.birlinn.co.uk

A Cameron Never Can Yield © Janette MacDonald Translation and other material © Bill Innes

By agreement with the families concerned, the royalties from this book will be donated to Erskine Hospital

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form without the express written permission of the publisher.

ISBN: 978-1-84341-039-3 eBook ISBN: 978-0-85790-519-2

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

Contents

List of Maps

Acknowledgements

Introduction

The Military Background

The Tank War

The Air War

The Highland Division

Escape

The Myths

A Cameron Never Can Yield

Gregor MacDonald

Mobilisation

Arrival in France

The Maginot Line

The Somme

Withdrawal

St Valery-en-Caux

The March

Escape

Re-captured

The Second Escape

Occupied France

Pay the Ferryman!

Vichy France

New Friends

The Tartan Pimpernel

The Work of Rev. Donald Caskie

Voyage to North Africa

The Traitor

Leaving Marseilles

Crossing the Pyrenees

Another Winter Trek

Spanish Prison

Zaragoza

The Concentration Camp

Brutal Treatment

Gibraltar

Going Home

Back with the Army

Under the Shadow of the Swastika

Donald John MacDonald

St Valery

The Great March

The Barges

The First Camp

Escape

The Seed Factory

‘Alabama’

Mühlhausen

Escape from the Salt Mine

Gestapo

Solitary Confinement

The Second Salt Mine

On the Move

Liberation

Freedom

The Way Home

Epilogue

The Boys That Are No More

The War Memorial

Big Archie Macphee’s Story

Suathadh ri Iomadh Rubha (Touching on Many Points)

Angus Campbell

The Phoney War

The German Onslaught

St Valery

The Journey to Thorn

Stalag XXa – Bromberg

A Bad Master

Groudenz – A Better Life

The Long March

Freedom

Appendix I 51st Highland Division on the Maginot Line

Appendix II The Salt Mines

Selected Bibliography

List of Maps

Map 1: The German assault, 10 May to 12 June 1940

Map 2: The Impossible Odds. The situation on 11 June 1940

Map 3: Positions around St Valery (based on a sketch by 2nd Lt ‘Ran’ Ogilvie, Gordon Highlanders)

Map 4: Gregor MacDonald’s escape route

Map 5: Approximate route of march from St Valery to the Rhine, June 1940

Map 6: Sketch map of the Thuringia region of Germany, showing places mentioned in D. J. MacDonald’s account

Map 7: Route of the long march from Stalag XXa, 9 January to 11 April 1945

Acknowledgements

The heroic campaign of the 51st Highland Division in 1940 was a theme of my childhood – especially after the war when so many of the young men of my home island returned from imprisonment. My interest was reawakened in 1988 when I had the privilege of interviewing some of the survivors for a Gaelic TV current affairs programme.

Sadly, their number is ever-diminishing but my thanks in particular to Archie MacVicar, Donald Alan Maclean, Donald Bowie and Murdo Maccuish who, sadly, are no longer with us.

None of the major contributors to this book is alive today but my debt to Donald John MacDonald is immeasurable – his poetry has been an inspiration to me for most of my adult life.

Archie Macphee was eighty-nine when I first met him, but still such an impressive figure that it is little wonder the Germans found him a handful!

I never had the opportunity to meet Angus Campbell or Gregor MacDonald but I am grateful to Donald John Campbell for his help with translation of his father’s work and for providing background information, and to Janette MacDonald for permission to use such a large section of her father’s book and other published material. Douglas Ledingham also gave permission to quote from his private memoir. Other important details came courtesy of Jo MacDonald of the BBC, Ronnie Black and Peter Bowie. Thanks also to Cailean Maclean for sight of copies of The Camp newspaper brought back from Stalag IXc by Kenny Mackenzie.

The families have all been most helpful with information and photographs and all readily agreed that royalties from this book should go to the Erskine Hospital for veterans.

But the greatest thanks of all must go to the veterans of the 51st Highland Division. It has been a privilege to meet so many of them. May this book remind us how much their generation suffered for the rest of us.

Bill Innes 2004

Map 1: The German assault, 10 May to 12 June 1940

Map 2: The Impossible Odds. The situation on 11 June 1940

Map 3: Positions around St Valery (based on a sketch by 2nd Lt ‘Ran’ Ogilvie, Gordon Highlanders)

Introduction

The gallant rearguard action in 1940 which led to the capture of most of the 51st Highland Division at St Valery-en-Caux may have burned itself into the consciousness of the older generation of Scots but it has never been given the wider recognition it deserves. Even in Scotland it has been forgotten that the men of the 51st were still fighting in France ten days after the evacuation of the main British Expeditionary Force from Dunkirk had been completed.

Many of the countless books about the war deal with the first eight months of the ‘Phoney War’ and the subsequent evacuation from Dunkirk, but very few mention St Valery other than in passing. Yet the defiant rearguard action of the Highland Division against overwhelming odds won the admiration of their final enemy Rommel as well as Allies such as de Gaulle who fought alongside them.

Lack of recognition even in the homeland of the Highland Division has allowed some myths to flourish in the intervening decades. Most persistent is the belief that Churchill deliberately sacrificed the Division as part of his grand scheme to keep the French in the war. The introductory chapters on military background attempt to clarify the chaotic sequence of events leading up to the fateful 12 June 1940 so that some of the legends may be reassessed.

However, the main purpose of this book is to put flesh on the bones of history by bringing together the recollections of four of the men in their own words. Relatively few accounts of the war were written by ordinary soldiers. The fact that two of these contributors were highly respected Gaelic poets adds further value to their assessment of the experience.

The word ‘hero’ has been devalued in our materialistic times and is now most likely to be applied to a sportsman who earns more in a month than some of these men earned in their lifetimes. In today’s compensation culture fewer of us are prepared to take responsibility for our own actions, far less put ourselves in mortal danger for the sake of comrades and country.

The ordinary soldiers who tell their stories in this book would not regard themselves as heroes – but it is a sobering challenge for us all to consider how we might have coped in the situations they endured.

We must not forget how much we owe them.

The Military Background

When war broke out at the beginning of September 1939 it found both Britain and France pitifully unprepared for confrontation with Germany. Memories of the horrors of the First World War were still vivid and during the intervening twenty years there had been few in either government willing to consider the possibility that there could ever be another such.

In 1914 the British Army had been a volunteer force and the cream of the country’s young men were eager to join the rush for glory in the war that was to be over by Christmas. As a result, many of the potential leaders of the future had died, revolver in hand, in the muddy quagmires of no-man’s-land, while leading their men against German machine-guns. It is difficult not to see some correlation between this futile waste and the subsequent decline of Britain as a world power.

Eventually that ‘war to end wars’ had cost Britain 700,000 men. But French losses numbered nearly twice as many at 1,322,000 – with nearly 4 million registered as disabled. The death rate among their servicemen was 16 per cent overall but among the officer class it was 19 per cent. Small wonder that many in France had little appetite for war. There were many right-wing thinkers who had considerable empathy with the doctrines of Hitler, perceiving him as a bulwark against Bolshevism. On the other hand, the French Communist Party, which had vociferously denounced Hitler, was thrown into some disarray by his non-aggression pact with Stalin in August 1939.

Like the British, the French had a policy of appeasement, culminating in the infamous 1938 Munich agreement which they signed together with Chamberlain. However, when Hitler occupied Prague in March 1939, Britain and France entered an entente to intervene if Germany attacked Poland. When this agreement forced France into the war in September there was some resentment that the few divisions of the British Expeditionary Force made such a minor contribution to the Allied armies.

There were many reasons for this. In Britain the usual low priority given to defence spending in peace time and the depression of the 1930s had ensured that much military equipment was obsolete. The need to defend and rule a far-flung empire meant that Britain’s military forces had to be thinly spread. By April 1938 the government had decided that, in the event of war with Germany, Britain’s navy and air force should make the main contribution.

Clearly the navy’s role was crucial and so it was given priority for capital expenditure. The late 1930s also saw considerable expansion of the RAF, centred on a general belief that the role of the bomber in destroying civilian morale would be the most important factor in another European war. The mantra of the time, ‘the bomber will always get through’, overlooked a basic flaw. New bombers such as the Blenheim might be faster than the biplane fighters still used by most RAF squadrons, but they were considerably slower than new monoplanes such as the Hurricane. They were to prove easy prey for the Messerschmitt 109s of the Luftwaffe.

The regular army was the Cinderella of the services. Trained to police the Empire, it was totally unprepared and ill-equipped to fight a European war. The hurried introduction of conscription in the spring of 1939 actually compromised the readiness of the regular battalions, as experienced men had to be detached to train the mixture of reservists and raw recruits. There was a massive shortfall of modern weapons, ammunition and equipment. War Office thinking was that it might take two years to bring the army to a state of readiness to take on Germany.

In the inter-war period, military thinkers such as Captain Basil Liddell Hart and Major General Fuller had attempted to convince the top brass of the importance of the tank in any future conflict. But their theories had been rejected by a blinkered establishment firmly wedded to the role of the cavalry. Liddell Hart in particular was later to be regarded as one of the foremost military thinkers of his time. By 1924 he was already advocating a change from the disastrous static trench tactics of the Great War to what he called an ‘expanding torrent’ method of attack using concentrated armoured forces. In response, Field Marshal Earl Haig admitted that aeroplanes and tanks might have their uses – but only as accessories to man and horse. He dismissed any suggestion that modern vehicles might supplant the cavalry in war. In 1934 Brigadier Percy Hobart successfully demonstrated the technique in an exercise on Salisbury Plain, but the establishment response was that such a method could not possibly work in a real war.

Though Liddell Hart’s writings found little favour within his own military establishment, they were translated into German and became a basic text for the German General Staff. In 1937, as personal adviser to Hore Belisha, the Secretary of State for War, Liddell Hart advocated a major expansion of armoured and anti-aircraft divisions. Even though German rearmament must have been obvious by then, these ideas fell on stony ground. Progress was made on another of his suggestions: that the infantry should be mechanised. In roles in which both Germany and France still used horses, the British Expeditionary Force had trucks. However, by September 1939 only half of the necessary lorries had been delivered so the shortfall had to be made good with hastily-requisitioned vehicles of questionable serviceability.

The French army was still heavily dependent on horse-drawn transport and cavalry. Their failure to mechanise the infantry was to prove a significant factor in the St Valery disaster. German divisions also used a large number of horses to transport men and to pull artillery pieces. In the latter role, however, they rapidly realised that slow transit-speed, aggravated by the cumbersome business of unharnessing and caring for horses before guns could be deployed, made it impossible to match the high-speed advance of forward units. Furthermore, the demands of feed-supply created enormous logistical problems in a dynamic situation. Unlike vehicles, horses require fuel whether or not they are being used.

Ironically, the punitive conditions imposed on Germany by the Treaty of Versailles in the wake of the First World War meant that rearmament there started from scratch, unhampered by a backlog of obsolete equipment. The Germans not only modernised ships, aircraft and weapons but developed Liddell Hart’s ideas into a new philosophy of the strategy and tactics of war which was to become notorious as Blitzkrieg (lightning war). One of the main architects of this new strategy was General Heinz Guderian, who gave a German perspective on the war in his book Panzer Leader.

It was principally the books and articles of the Englishmen, Fuller, Liddell Hart and Martel that . . . gave me food for thought. These far-sighted soldiers were even then trying to make of the tank something more than just an infantry support weapon . . . it was Liddell Hart who emphasised the use of armoured forces for long range strokes, operations against the opposing army’s communications and also proposed a type of armoured division combining panzer and panzer-infantry units . . .1

Rather than digging in to static entrenchments as in 1914–18, Guderian advocated direct attack concentrated on enemy lines at the weakest point so as to break through the rear. Whereas old-fashioned military operations had been bedevilled by inter-service rivalries and mutual suspicion, he envisaged cooperation on a hitherto undreamt-of scale. Paratroopers, dive-bombers, artillery and modern fast Panzers would work together to pulverise the opposition without necessarily waiting for the support of conventional troops. The essential coordination was to be achieved through the use of radio – which would also permit staff officers to abandon the conventions of the previous war and move with their front line troops.

Lest it be thought that Britain and France had a monopoly on blinkered thinking, it must be recorded that Guderian’s revolutionary theories encountered considerable resistance among the German old guard. In 1931 General Otto von Stulpnagel told him: ‘You are too impetuous. Believe me, neither of us will see German tanks in operation in our lifetimes!’ The concept of generals leading from the front also found little favour with the General Staff.

But Guderian’s ideas captured the imagination of Hitler himself. The speed and ferocity of the philosophy was to take the rest of Europe completely by surprise. Even when some parts of the theory were put to the test in Poland in September 1939 – so successfully that the country was taken over in eighteen days – Britain and France failed to learn the lessons.

The Germans were surprised and relieved that France did not launch an attack while the bulk of the Wehrmacht was committed in the east but Allied military thinking was still rooted in the static tactics of 1914–18. French strategy was centred on defence against invasion rather than offence. In the interwar years they were lulled into a sense of false security by the construction at vast expense of the Maginot line of mammoth fortifications, which ran the length of their common boundary with Germany. A plan to extend the line to the Channel coast along the border with Belgium had foundered on Belgian government protests that this might endanger Germany’s pledges to respect Belgian neutrality in any future war with France. The fatal French assumption that their border with southern Belgium was sufficiently protected by the natural barrier of the Ardennes hills engendered further complacency.

When the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) moved to France they were dismayed at the poor quality of defences along the so-called ‘Little’ Maginot Line north of the Ardennes on the Belgian border. Staff officers considered themselves fortunate that the relative inactivity of the winter of 1939–40 gave them a breathing space to bring the divisions and defences up to battle readiness. These were the months of the so-called Phoney War and the First World War static mindset caused them to be spent in the construction of elaborate lines of trenches, pillboxes, anti-tank revetments, communication networks and even rail supply lines along the Franco-Belgian border.

The commander of the BEF, Lord Gort, had been a most distinguished and highly decorated officer with the Grenadier Guards in the First World War. In this new war he soon acquired a reputation as one who was more concerned with the detail of planning rather than with overall strategy. The BEF was under French command and the French plan in the event of a German invasion of Holland and Belgium was to move forward to the river Dyle, linking with the Belgian army to prevent a takeover of the whole of Belgium.

From the British point of view this had the advantage of denying the Luftwaffe air bases dangerously close to Britain. But, in order to protect their neutrality, the Belgians refused the Allies permission for any preparatory work on defences at the so-called Dyle Line. So when the Germans eventually flooded into the Low Countries on 10 May 1940 the Allied divisions abandoned their meticulously constructed positions for ill-prepared ones at the Dyle.

In Germany Guderian’s revolutionary ideas had gained ground. The principal advocate of a concentrated tank assault through the lightly defended Ardennes sector was General Erich von Manstein, later regarded by many as one of the most able of the German military thinkers. Such a move, in coordination with an attack on the Low Countries, would cut the French forces in half and form a classic pincer movement to trap Allied divisions in Belgium. Like original thinkers elsewhere, however, his ideas were initially rejected by the High Command and in January 1940 he was moved sideways to command an infantry corps on the grounds that he lacked the experience for a tank corps. This manoeuvre to get rid of an original thinker regarded as too pushy backfired for it led to him having a meeting with Hitler himself. The Führer was so impressed by Manstein’s plan that he soon began to think of it as his own.

The German High Command did indeed have every intention of repeating First World War tactics and attacking only through Belgium and Holland – the so-called Schlieffen plan. Hitler’s intention to implement it in November 1939 was frustrated by atrocious winter weather so it had to be postponed several times, until January 1940. However, on the 10th of that month an officer carrying its details took an unauthorised flight and his aircraft was forced by bad weather to land in Belgium. The knowledge that the plan might now be known to the Allies gave rise to a hurried reappraisal of Manstein’s ideas. It is ironic that when the plan was finally implemented he himself was allowed no part in it. But Germany was fortunate that Guderian shared Manstein’s views; so did the man who was to become one of the most famous generals of the war – Erwin Rommel. Although he had no experience of tanks before being given command of 7th Panzer Division in February 1940, his inspired leadership from the front was to be a key factor in its success.

However, it was Guderian who took the Manstein plan a stage further. Although the German High Command eventually agreed that the Panzer divisions should make the initial assault through the Ardennes to cross the Meuse, conventional wisdom decreed that they should then wait about ten days for infantry divisions to catch up and consolidate before resuming the advance. Such were the views expressed when the generals of Rundstedt’s Army Group A met Hitler to discuss the plan in early March.

Guderian argued that the Supreme Command should decide whether his objective was to be Amiens or Paris. Once across the Meuse, his own view was that he should immediately continue his drive past Amiens to the English Channel. The infantry generals doubted whether he would even get across the river but Hitler was impressed.

I never received any further orders as to what I was to do once the bridgehead over the Meuse was captured. All my decisions, until I reached the Atlantic seaboard at Abbeville, were taken by me and me alone. The Supreme Command’s influence on my actions was merely restrictive throughout.

Heinz Guderian Panzer Leader

The Allies still assumed that any German invasion would follow the pattern of the 1914. The French High Command continued to cling to the belief that no attack with armour could be launched through the Ardennes, despite the evidence of one of their own pre-war exercises in 1938 which successfully demonstrated that such an attack was entirely feasible. This unexpected result was dismissed by the French Supreme Commander, General Maurice Gamelin, on the grounds that it could never happen in a real war because reserves would be available to contain any breakthrough.

When real war did come, however, crack front line troops had been moved from the Ardennes sector and its defence had been entrusted to a mere seven cavalry regiments and ten infantry divisions of mostly reservist troops. During the Phoney War these forces had singularly failed to impress General Alan Brooke2 of the BEF with their lack of discipline and esprit de corps. There were no reinforcements in the sector.

In fact there were many roads in the Ardennes suitable for tanks. Even where trees had been felled to obstruct some routes, the typical thoroughness of German planning ensured that their pioneer battalions were equipped with chain saws to deal with any blockages the Panzers could not push aside or bypass. Far from being an insuperable barrier, the hills held some advantages for the Germans. Their massive build-up of forces was masked from aerial surveillance by tree cover. More importantly, once through the hills and across the river Meuse, the relatively flat roads of northern France offered ideal tank terrain compared to the marshes and canal networks of Flanders.

In 1938 the German army was relatively small. But by May 1940 there had been massive expansion. Facing Belgium and Holland to the north were two armies in Army Group B under General von Bock. To the south behind the Siegfried Line3, which faced the Maginot Line, were another two armies under General von Leeb.

But, thanks to Manstein, the greatest change had occurred in the centre to the east of the Ardennes. The main Army Group A under General von Rundstedt now had four armies consisting of forty-four infantry and seven armoured Panzer divisions. This huge force built up (causing massive traffic jams on the roads) without apparently causing any undue alarm in the French General Staff. It seems that Gamelin believed that any German attack was unlikely to take place before 1941 – and even then would be made through Belgium. So confident was he of this judgement that large numbers of French soldiers were allowed to go on leave in the first few days of May.

On 10 May German Army Group B under von Bock attacked Holland and Belgium in a classic demonstration of the effectiveness of blitzkrieg. Bombers, troop-carrying gliders and a relatively small number of paratroopers combined in a daring assault. Half the Belgian air force was destroyed on the ground, key bridges were secured before they could be blown up and Rotterdam was heavily bombed.

The Allies reacted immediately in accordance with the French plan and moved forward to the Dyle to link up with the Belgian army. The move revealed a further crucial complication. Allied pre-war planners had failed to anticipate the importance of adequate communications. Both armies continued to rely on antiquated field telephone lines together with despatch riders and even flags and heliographs. These methods were supplemented by the use of a public telephone system considerably more primitive than today’s.

However effective such systems might have been in the static conditions of 1914–18 , their shortcomings were cruelly exposed in the dynamic battlefield of the new German strategy. Even where signallers had time to set up new lines they were torn apart by artillery or tank treads. Despatch riders had the daunting task of navigating strange roads congested with refugees while seeking units forever on the move. Their vulnerability to enemy action meant that critically important messages might never arrive.

A more fundamental problem was that the underlying system of pre-planning and transmission of orders through an over-complicated and ill-defined command structure was still geared to the more leisurely pace of a static war. For security reasons messages were sent in code, which caused much time to be wasted in encrypting and decoding. (It was said that it might take forty-eight hours for Gamelin’s decisions to reach his commanders in the field.) French and British cooperation was further bedevilled by lack of fluency in each other’s languages. The overall failure of communications has to be considered a major contributory factor in the subsequent debacle.

To make matters worse, when Guderian’s Panzers from Rundstedt’s Group A started pouring through the Ardennes and over the Meuse, indecision and confusion ensued in the French High Command. In the rapidly developing crisis both Britain and France had major leadership changes which were to prove decisive in differing ways.

When Winston Churchill took over as British Prime Minister on 10 May he found himself in an unenviable situation. Nowadays it is easy to forget how much he was distrusted by the establishment of the time and how little backing he had even within his own party. He was faced with a stream of depressingly bad news from France, which led to a general atmosphere of defeatism. Britain was committed to helping France, her principal ally. However, there was considerable doubt in the War Cabinet as to the strength of the French resolve. Nevertheless, the longer the German advance was delayed in France, the better chance Britain had of preparing for the expected invasion. Britain therefore had to support France as long as possible. At considerable personal risk, Churchill made the first of several air journeys to France within days of taking office in a vain attempt to bolster visibly flagging morale.

By 19 May, when the increasingly ineffective French Commander-in-Chief Gamelin was replaced by the 73-year-old Maxime Weygand, the situation was already slipping out of control. Weygand soon became pessimistic about his chances of fighting a war in 1940 with a 1918-standard army still heavily reliant on horse-drawn transport and cavalry in the front line.

The Allied move to the Dyle had left the way clear for Guderian’s Panzers to race past Amiens to the Channel ports of Boulogne and Calais. With Army Group B advancing into Belgium from the east and Army Group A following Guderian to the west in France, it became clear that the BEF and French forces in Belgium were about to be trapped in a pincer movement.

The entire BEF was technically under the command of the French General Georges. However, its commander Lord Gort had a get-out clause in his standing orders which permitted him to appeal directly to the British government if the safety of the BEF was threatened. Gort took full advantage of this loophole to withdraw his troops to Dunkirk. The famous evacuation of 338,000 men was accomplished thanks to the heroic feats by the Navy and a flotilla of assorted civilian craft. However, massive quantities of arms and support equipment had to be abandoned.

These major losses included 82,000 vehicles, 7,000 tons of ammunition, 2,300 pieces of artillery (including nearly all the new 25lb heavy guns) as well as millions of gallons of fuel. Losses of smaller weapons included 90,000 rifles, 8,000 Bren guns and 400 anti-tank rifles. Although much equipment was disabled, significant amounts fell into grateful German hands.

In order to maintain civilian morale in Britain at the time it was necessary to portray Dunkirk as a heroic achievement and that is how it is remembered today. Understandably, many in France saw it as a betrayal by the perfidious British ‘willing to fight to the last French breast’. German propaganda seized every opportunity to exploit this view. However, even in France it is now increasingly recognised that Gort’s assessment of the BEF’s hopeless situation was accurate and his action in withdrawing his men to fight again another day was justified by later events.

Gort was a convenient scapegoat for a disaster that was largely due to peacetime neglect of the army. Later in the war his reputation was redeemed. Heroic work as Governor General during the siege of Malta earned him belated promotion to Field Marshal. However, the keenly-felt disgrace of Dunkirk undoubtedly hastened his early death in 1946.

The Tank War

As already discussed, the importance of the tank in war had not been fully appreciated by the Allies despite the warnings of Liddell Hart in Britain and de Gaulle in France.

The BEF set out for France with only two divisions of Matilda 1 and 2 tanks. The 11-ton Matilda Mk1 had been designed with an operating speed of 8mph so that the infantry could keep up with it! Furthermore, its car engine was to prove unreliable and it was armed only with a machine-gun which was useless against Panzers. Although its 60mm armour plating was sufficient to deflect German tank shells, it was still vulnerable to heavy artillery. Its successor, the 26-ton Matilda Mk2 was a more formidable weapon capable of twice the speed. In addition to its machine-gun it carried a two-pounder cannon – although this was not capable of firing high explosive shells. It is indicative of the expected role of the Matildas within a static war that they were designed to cover a mere ten miles between overhauls. The intention was that tanks should be transported by train or other means to the front. However, they covered 60 miles on their tracks in the hurried advance to the Dyle – and then had to return.

In 1940 the French had even more tanks than the Germans. The French Char B1 was an impressive sight, weighing in at a massive 32 tons and carrying a 75mm howitzer as well as a 37mm and a machine-gun. However, its maximum speed was only 17mph and the 75mm gun could not be traversed. The consequent need to manoeuvre the tank itself to train the howitzer was a fatal flaw in such a cumbersome machine. Even more significantly, there was only room for one man in the turret, which meant that the tank commander also had to load and fire the guns. This not only led to an unacceptably slow firing rate but also substantially degraded his ability to command the tank. Despite these drawbacks the Germans had considerable respect for the Chars.

The German Panzers were extremely efficient fighting machines armed with 37mm or 75mm cannon plus two or three machine-guns. Their armour was typically less than half the thickness of the Allied tanks but this lighter weight contributed to their ability to reach speeds of over 25mph. In theory they were not supposed to fire their guns while in motion but Rommel’s advancing tanks behaved like a naval squadron in line astern, firing broadsides left and right. Rommel found that the alarm and confusion thus created more than made up for any loss of accuracy. The Panzer regiments were also supplemented by large numbers of lighter Czech 38(t) tanks captured after the occupation of Czechoslovakia.

The use of radio was of fundamental importance to the Panzer operation. Both Guderian and Rommel could travel with their leading formations and keep in contact with their unit commanders while being on the spot to take key decisions. Command vehicles can be identified in war photographs by the rather ungainly horizontal frame aerials they sported. The few Allied tanks fitted with radio were bedevilled by defects and flat batteries. The use of signal flags was hardly an acceptable substitute.

But on 21 May there was a counter-attack at Arras by the 4th and 7th Royal Tank Regiment with the support of the Durham Light Infantry which remains an intriguing example of what might have been. This should have been a combined operation with 250 tanks of the French 3rd Light Mechanised Division but they were short of fuel and, with their men exhausted, had trouble getting into position in time.

The British tanks had just completed the round trip of 120 miles to the Dyle line and back without a servicing break. Nevertheless, the attack with forty-five Mk1 and twenty Mk2 Matildas caused panic and confusion among an unblooded battalion of the SS.

Rommel’s 7th Division Panzers had their first shock of the campaign when they found that their rounds just bounced off the British armour. It was reported that one Matilda took fourteen hits without a single penetration. Rommel thought he had been attacked by a much greater force but, ever resourceful, decided to bring divisional artillery and 88mm anti-aircraft guns to bear. These latter had armour-piercing shells as well as flak rounds and proved capable of destroying tanks at a range of 2,000 metres. They continued to pose a threat to Allied tank formations for the rest of the war.

Rommel was living proof that fortune favours the brave. On 14 May his tank had been hit and he was very nearly captured by the French. In this engagement at Arras his aide was killed by his side as they examined the same map. In post-war debriefings General von Rundstedt confessed to Liddell Hart that this was the most critical moment in the drive to the coast:

‘. . . for a short time it was feared that our armoured divisions would be cut off before the infantry divisions could come up to support them. None of the French counter-attacks carried such a threat as this one did.’

Liddell Hart The Other Side of the Hill

However, the main difference between the opposing armies was a strategic one. The French had scattered their armour in small units throughout the front in support of the infantry. The Germans concentrated theirs in highly mobile divisions which could operate at speed independently of infantry. Had the French been able to make a concentrated attack on the vulnerable and over-stretched flanks of the advancing Panzer divisions then the whole history of the campaign might have been changed. When interviewed by Liddell Hart after the war, Guderian said:

‘The French tanks were better than ours in armour, guns and number, but inferior in speed, radio-communication and leadership. The concentration of all armoured forces at the decisive point, the rapid exploitation of success and the initiative of the officers of all degrees were the main reasons for our success in 1940.’

Liddell Hart The Other Side of the Hill

The Air War

Often unseen by those you helped to save

You rode the air above that foreign dune

And died like the unutterably brave

That so your friends might see the English June.

John Masefield’s tribute to the Spitfire pilots

The lack of defensive air cover is a recurrent theme in naval and military reminiscences of the time. Yet the RAF took heavy losses during the period before and immediately after the fall of France. In order to understand the apparent discrepancy in perceptions, a few facts may be helpful.

Fighters such as the Spitfire and Hurricane were at their best at high altitude and so conducted their dogfights at heights where they were invisible to observers on the ground – save for the contrails produced in certain meteorological conditions which, for example, hallmarked the skies during the Battle of Britain. Because they were designed to defend the United Kingdom their maximum endurance was about ninety minutes – considerably reduced at combat power settings. By the time they had crossed the Channel, their fighting time was inevitably brief. It was only with the arrival of long-range North American Mustangs much later in the war that bomber squadrons could be provided with a fighter escort into Germany.

These early British fighters, armed only with machine-guns4, were useless in the ground-attack role. This was delegated to fighter-bombers such as the lumbering Blenheim and the obsolescent Fairey Battle. These were deployed away from the front line in an attempt to slow the advancing German columns and damage bridges and communications. But their bomb-load was small and its effectiveness much reduced by primitive bomb-aiming methods and high failure rates. Neither France nor Britain had realised that bombers diving almost vertically out of the sky could deliver their load against small targets with much greater precision. A Vickers test pilot who had flown the Junkers 87 dive-bomber in 1938 reported so enthusiastically on it that Vickers management tried to persuade the Air Ministry of the need for such a machine. They were told that their pilots should mind their own bloody business!

Many Luftwaffe pilots were already battle-hardened veterans of the Spanish civil war and the Polish campaign. The blitzkrieg typically opened with waves of Ju87 Stukas hurtling out of the sky from fifteen thousand feet to drop their deadly load. The psychological terror effect on troop morale was further reinforced by sirens fitted to their undercarriage legs, which created the screaming sound so often heard on old newsreels.

Not only did lack of speed make RAF bombers extremely vulnerable to enemy fighters but they also had to deal with a level of anti-aircraft fire far in excess of that available to the Allies, whose leaders had not anticipated the crucial importance of anti-aircraft weapons. The French Supreme Commander, General Gamelin, believed that air forces would fight one another, leaving the proper business of war to the armies. By contrast, German divisions had flak batteries of the formidable 88mm guns which were also used with great success against tanks.

Bombers forced to attack precision targets at low level in order to achieve any accuracy also took heavy punishment from German small arms fire. Not only did German divisions have many more machine-guns per unit than the Allies but they also used tracer ammunition which allowed the ‘hosepipe’ system of targeting and better concentration of fire. By comparison, the chances of damaging (or even hitting) an aircraft with a .303 rifle were small.

In terms of sheer numbers, the French Air Force was probably superior to the Luftwaffe. However, many of these aircraft were obsolete and more were lost in training accidents than through enemy action. Their most promising fighter, the Dewoitine D.520 (not unlike a Spitfire in appearance), had been ordered in thousands but fewer than forty had been delivered by May. For reasons difficult to understand, many hundreds of their other aircraft were held in reserve and never committed to operations at the front.

In the later Battle of Britain the ultimate success of the RAF owed much to the newly developed radar network. The early systems were at their best in picking up aircraft approaching coastlines. When RAF fighter and light bomber squadrons were based in France at the outbreak of war, mobile units went with them; but these were primitive by today’s standards and largely ineffective over land. By the time a threat was identified, even single-seat fighters had little time to get airborne and climb to the necessary altitude to engage the enemy. As a result many aircraft were caught on the ground. Bombers were even more vulnerable. On 11 May nearly all of 114 Squadron’s Blenheims were destroyed in a bombing raid by Dorniers of the Luftwaffe.

Worse was to come. On one day, May 14, over a hundred aircraft attacked the pontoon bridges the assault forces were building across the Meuse at Sedan. But by then the Germans had their flak batteries in place. Forty-five RAF Battles and Blenheims and forty-seven French LeO 45 aircraft failed to return – clearly an unsustainable level of loss, which effectively ended daylight bombing raids. The heroic sacrifice did delay German crossing of the Meuse but not for long enough to influence the final result. To make matters worse, twenty-seven Hurricanes were lost in dogfights with Me 109s.

While this was the worst day of the entire war for RAF aircraft losses, a much more serious problem was the attrition rate amongst some of the most experienced aircrew in the service, who should have formed the core of the subsequent defence of Britain. These losses were aggravated by failure to fit any armour plating to fighter cockpits – because it might affect aircraft balance! On their own initiative, No. 1 Squadron salvaged some from a wrecked Battle and put it in their Hurricanes. The modification was soon extended to other aircraft and later proved to be another decisive factor in the Battle of Britain.

By the 19 May, the rapid German advance posed such a threat to RAF forward bases that squadrons had to be progressively withdrawn to home bases in England. The disruption caused by this move temporarily reduced fighting capability.

It is probably true that inter-service cooperation could have been a lot better before and during the early stages of the war. Even with today’s infinitely more sophisticated communications, ‘friendly fire’ incidents still occur. In the Second World War it was accepted by RAF pilots that flying close to Navy ships was a dangerous thing to do. At Dunkirk they were even fired on by British troops because a rumour had spread that the Luftwaffe were using captured RAF aircraft. The problems were aggravated by pre-war planners’ failure to appreciate the importance of adequate radio communications. Even within the RAF, there were several incidents of Blenheim bombers being attacked by Hurricane fighters.

Germans were not immune from ‘friendly fire’ incidents. Guderian records being attacked by the Luftwaffe on the 20 May near Amiens. He promptly ordered his flak batteries to shoot the offending aircraft down!

Troops being evacuated from Dunkirk were particularly critical of the perceived lack of air cover. The fleet which so heroically rescued the majority of the troops suffered heavy losses. Yet there was a standing fighter cover of up to forty-eight RAF aircraft over the beaches. Bearing in mind that Goering had promised Hitler that the destruction of the BEF could be left to the Luftwaffe, the fact that 338,000 men were taken off speaks for itself. It is obvious that Allied losses would have been considerably more had his aircraft been allowed free rein to attack the troops and the armada of little ships that saved them.

Legendary Luftwaffe ace Adolf Galland shot down his first Spitfire over Dunkirk, but in The First and the Last made this comment on the operation.

It merely proved that the strength of the Luftwaffe was inadequate, especially in the difficult conditions for reinforcement created by the unexpectedly quick advance and against a determined and well-led enemy who was fighting with tenacity and skill. Dunkirk should have been an emphatic warning for the leaders of the Luftwaffe.

In particular, Dunkirk was to be the beginning of the end for the Stukas which had proved so devastating in the early days of blitzkrieg. Their dive-bombing tactics had considerable success against the assembled flotillas, due mainly to the failure to anticipate the need for anti-aircraft weapons. Very few Royal Navy ships of the time had guns which could be elevated enough to deal with dive bombers. However, the slow speed and high ‘greenhouse’ cockpits of the Stukas made them very vulnerable to RAF fighters. In the later Battle of Britain their losses were such that they had to be withdrawn from the action.

At the time of Dunkirk, however, Air Chief Marshal Sir Hugh Dowding did have to point out to the War Cabinet that he was losing twenty-five Hurricane fighters a day to Messerschmitts, while the number emerging from the factories was only four. It was fortunate for Dowding and Britain that Lord Beaverbrook was appointed Minister of Aircraft Production. Beaverbrook’s robust attitude to cutting red tape made him a hated figure to bureaucrats but greatly increased the rate of aircraft delivery to the squadrons.

However, the loss of experienced pilots when many potential replacements had yet to fly in a frontline fighter was the more serious problem. In the first half of June 1940 the French made frequent appeals for more RAF fighter cover but Dowding argued that he would be unable to defend Britain against the likely German invasion if his fighting strength fell below 25 squadrons.

Churchill’s secretary, Sir John Colville, was clearly persuaded by the logic of Dowding’s case: ‘the effective range of our fighters will not enable them to go far up the Seine, but it would be suicidal to send them to aerodromes in France where they will be destroyed on the ground.’ Subsequent events in the crucial Battle of Britain later that year were to vindicate Dowding’s judgement. By denying the Luftwaffe the prerequisite mastery of the skies the RAF effectively blocked the threat of invasion – but it was a damn close-run thing.

The Highland Division

I can tell you that the comradeship in arms experienced on the battlefield of Abbeville in May and June 1940 between the French Armoured Division, which I had the honour to command, and the valiant 51st Highland Division under General Fortune, played its part in the decision which I took to continue fighting on the side of the Allies unto the end no matter what may be the course of events.

General Charles de Gaulle at Edinburgh 20 June, 1942

This summary of events leading up to 12 June is of necessity brief. However, a detailed account of the many actions involving individual units can be found in Eric Linklater’s The Highland Division (HMSO 1942) or Saul David’s Churchill’s Sacrifice of the Highland Division (Brassey’s 1994), which is more comprehensive and a much better book than its catchpenny title would suggest.

In September 1939 the 51st was a Territorial division and its three brigades consisted of nine infantry battalions drawn from such famous regiments as the Black Watch, Seaforth Highlanders, Cameron Highlanders, Gordon Highlanders and Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders. In addition, there was one anti-tank and three field regiments of Royal Artillery, Royal Ordnance, four companies of Royal Engineers, Divisional Signals and three field ambulance units of the RAMC. Supply and transport were provided by the RASC. Significantly, there was no anti-aircraft provision.5

In command was Major General Victor Fortune, who had fought with distinction with the Black Watch in the First World War. He soon established a reputation as a commander who cared about his men and made every effort to get to know them.

After the division assembled in Scotland, the few weeks of preliminary basic training in drill and weapons were hampered by a shortage of equipment. At this stage many men were still wearing uniforms of 1918 vintage, with some of the newer conscripts still in civilian clothes.

Pre-war Highland regiments wore the kilt and there was considerable resistance when battledress was introduced a few months later. (The regular battalion of the 1st Camerons was credited with being the last Highland unit to go into action in kilts when they fought at the river Escaut in May 1940.)

The Division then moved to the Aldershot area in the south of England where the full time Regular Army training had to be compressed into a period of two to three months. After being given a week’s leave just after Christmas they sailed for France in January 1940. As their accounts reveal, the men were not impressed by the quality of their billets.

Further drilling and training continued, despite the Arctic weather of one of the worst winters in living memory. In February, when the Division moved to join the rest of the BEF near the Belgian border, conditions varied from snow and extreme cold to continuous rain and mud. Initially the 51st was held behind the main front line near Béthune because the other divisions intended for the sector were kept in reserve to help Finland against Russian invasion.

Accommodation was only marginally better but there were compensations. The pay of a private soldier of the time was about four shillings (20p) a day. Even then, that was not much – but it was twice as much as their French equivalents earned. The men soon discovered that a plate of eggs and chips could be washed down with vin ordinaire for about four pence (less than 2p!). Evenings in the café were an attractive alternative to the boredom of the billets – even if the unaccustomed level of alcohol consumption gave rise to the odd fracas.

Training continued, although it had to be combined with the arduous work of constructing the defences of the so-called ‘Little’ Maginot Line. However, every opportunity was taken to use the five pipe bands in public relations exercises in local towns. Early in March it was decided to strengthen the Division by replacing some of the TA battalions with Regulars who had been in France since the early days of the war.

The 1st Black Watch, 1st Gordons, 2nd Seaforth and 17th and 23rd Field Artillery Regiments replaced the 6th Black Watch, 6th Gordons, 6th Seaforth and 76th and 77th Royal Artillery. The 1st Lothians and Border Horse replaced the Fife and Forfar Yeomanry as the light armoured brigade.

On 28 March the Division took over the section of the Belgian frontier between Bailleul and Armentíres. Conscious that many of the troops had no experience of facing the enemy, the BEF had been rotating small units of officers and men to the front line at the real Maginot line in the Saar region. The 1st Black Watch had already had a tour of duty over Christmas in the area but in the middle of April it was decided that the 51st should be the first full BEF division to be deployed there.

Supplemented by ancillary units, the division now mustered about 22,000 men. Under French command, they were allotted a sector of the German border between Luxembourg and the little town of Bouzonville. The intention that this was to be just a short posting was to be overtaken by events.

The famous fortifications which had absorbed so much of the French military budget had several lines of defence in an area which had been evacuated of civilians.

a) The Ligne de Contact (Line of Contact), approximately seven miles in front of the forts, faced the equivalent German Siegfried line across no-man’s-land.

b) The Ligne de Soutien (Support Line) was non-continuous and did not feature in the Highland Division’s sector.

c) The Ligne de Recueil (Recoil Line) was a defensive line in front of the forts.

d) The Ligne d’Arrêt (Stop Line) behind the forts was intended to be the final ‘backstop’ position. It had not yet been completed.

Officers and men were disappointed at the poor quality of their accommodation and the lack of defences in depth.

There were many things to admire about the French Army, but their preparation of proper defences in the front and rear of the Lignes Maginot was not one of them . . .

Return to St Valery Sir Derek Lang

It is probably true that every military unit taking over from another would find much that they would like to change but the Scots were particularly unimpressed by the log huts which formed part of the forward defences. These may have been built because the wetness of the ground did not favour the usual dugouts but they had the crucial drawback of not being bullet-proof.

This was still the period of the Phoney War; both Britain and Germany were concentrating on building up forces and weapons for the conflict still to come. Hitler had wanted to commence the war in the west in November 1939 but the unusually severe winter was a major factor in causing a postponement. The Scots were surprised to find that the French troops they were relieving seemed to have settled into a comfortable accommodation with the opposing Germans; every effort was made not to engage in any action that might disturb the status quo and so risk escalation of the conflict.

Initially, therefore, there was very little action on the frontier apart from some light skirmishing by night patrols – as Angus Campbell records. The 7th Argylls seem to have been particularly active but units were cycled between the various lines of defence in order to expose the maximum number to front line experience. In one incident, Donald Bowie, a member of my own family and close friend of Donald John MacDonald, was among the first to be taken prisoner when an isolated forward post of the 4th Camerons was overrun.6 However, the Camerons found Gaelic better than any code when it came to frustrating German tapping of their telephone lines.

As has been mentioned, Gamelin’s complacency about the imminence of any attack from Germany led to permission being given for many men to go on leave at the beginning of May. As the 51st were under French command, this generosity also extended to them. Donald John MacDonald was one of the islanders who benefited, but by the time they reached Glasgow news had broken of the German attack on 10 May. To their surprise, there was no recall and they were allowed to complete their leave.

Meanwhile, although Guderian’s divisions bypassed the Maginot Line when they broke through to the north near Sedan, the men of the 51st found the temperature of conflict in their sector rising rapidly as forces from the Siegfried Line made feint attacks on the Maginot Line to distract from the main thrust through the Ardennes to the north.

On 13 May an early morning artillery barrage announced a major German assault on the whole front. It was the turn of the 1st and the 4th Black Watch and the 5th Gordons to be in the front line; on their right, the 4th Seaforths had just relieved the 4th Camerons. The Black Watch took the brunt of the early attacks and suffered heavy losses around their outpost at Betting. However, the Division gave a good account of itself and General Condé of the French 3rd Army praised their fighting qualities and high morale as ‘renewing the tradition of Beaumont-Hamel.’7

As French divisions on either flank were driven back, the 51st positions in front of the Maginot line became untenable and they were withdrawn – initially to the Ligne de Recueil.

The rapidly developing main German two-pronged assault soon threw French military planning into disarray. Orders were conflicting and travel arrangements chaotic. Initially the French assumed the German attack would be directed at Paris and the 51st were to form part of the defence force. The Highlanders were first ordered to Varennes with a view to assisting in dealing with that threat. When Guderian’s divisions swept past to the north heading for Amiens, the troops were redirected by rail on a circuitous route towards Rouen via Orleans and Tours, far to the south and west of Paris. The trains were so old and slow that on up-gradients men had to get out and push!

Meanwhile their motorised vehicles took a more direct 300-mile northerly route but ran into their own problems. German propaganda radio broadcasts in French had caused thousands of civilians to flee to the west using every possible kind of transport for their precious possessions. Vehicles abandoned when they ran out of petrol added to the congestion and chaos. The subsequent jams provided easy targets for the Luftwaffe, who seemed to have a deliberate policy of attacking the pathetic refugee streams in order to obstruct military movements.

It took six days to reunite men and machines but by then Guderian’s high speed thrust had cut them off from the rest of the BEF, which was being hounded towards Dunkirk. On 28 May they reassembled along the line of the river Bresle and on 2 June moved towards Abbeville on the left flank as part of the French IX Corps to help repulse the German advance across the Somme.

They were to be assisted by the 1st Armoured Division, newly arrived from England. This division was far from full strength and had arrived without its infantry or artillery. It had 250 light tanks and cruisers which were more suited to reconnaissance than any duel with Panzers. Being lightly armoured they were extremely vulnerable to anti-tank weapons. The division had few spares, no bridging equipment and serious deficiencies in wireless equipment. On 27 May, after a series of conflicting orders, it was thrown against the German bridgeheads west of the Somme and nearly half of the tanks were lost to enemy guns and mechanical breakdowns.

On 29 and 30 May the much more powerful French 4th Armoured Division under the command of the up-and-coming General de Gaulle had more success but without adequate artillery and infantry support was unable to dislodge the enemy.

On 4 June the 51st together with the French 31st Infantry Division and 2nd Armoured Division made a new attempt (described by Angus Campbell and Gregor MacDonald) to take back the high ground overlooking Abbeville and the Somme. Due to inadequate intelligence as to the real strength of the enemy, the Division suffered heavy casualties with 152 Brigade losing twenty officers and 543 men – mainly from the 4th Seaforths and 4th Camerons.

There were some successes. The 1st Black Watch and 1st Gordons pushed the enemy back in their sector; but without corresponding success on either side they were in danger of being isolated. To their great disappointment they had to fall back to their original positions.

The following day the Germans launched their main assault across the Somme and the whole division was slowly forced backwards. The 5 June was a particularly hard day for the Argyll & Sutherlands as companies of the 7th Battalion were isolated and cut off. By the end of a day distinguished by many heroic actions against a far more numerous enemy, twenty-three officers and 500 men had been killed, wounded or captured. Three days later Major Lorne Campbell managed to lead the remnants of A and B Companies back through enemy lines to rejoin the Division at the river Bresle.

However, these losses left no option but further withdrawal to the river Béthune south of Dieppe. By 8 June, with the situation becoming desperate, the War Cabinet wanted them to fall back towards Rouen so that they could be taken off from the port of Le Havre, where many of them had originally landed.