Stairs and Whispers E-Book

Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Nine Arches Press

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Sprache: Englisch

Sandra Alland, Khairani Barokka and Daniel Sluman co-edit Stairs and Whispers: D/deaf and Disabled Poets Write Back, a ground-breaking anthology examining the poetics of disabled and D/deaf cultures. With contributions that span Vispo to Surrealism, and range from hard-hitting political commentary to intimate lyrical pieces – these poets refuse to perform or inspire according to tired old narratives. Five years after the seminal U.S. anthology, Beauty is a Verb, Nine Arches Press brings you its exciting UK progeny: Stairs and Whispers. The first of its kind and packed with fierce poetry, essays, photos and links to accessible online videos, this book showcases a diversity of styles, opinions, and survival strategies for a world that often works to shut us down.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 212

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Stairs and Whispers: D/deaf and Disabled PoetsWrite Back

Stairs and Whispers: D/deaf and Disabled Poets Write Back Edited by Sandra Alland, Khairani Barokka and Daniel Sluman

Print ISBN: 978-1-911027-19-5 ePub ISBN: 978-1-911027-30-0

Copyright © remains with the individual authors.

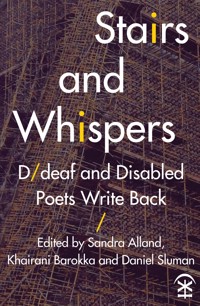

Cover artwork ©Khairani Barokka: ‘Tate Modern Extension, 2015’

All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form or by any means, graphic, electronic, recorded or mechanical, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

The individual authors have asserted their rights under Section 77 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identified as the authors of their work.

First published May 2017 by:

Nine Arches Press

PO Box 6269

Rugby

CV21 9NL

United Kingdom

www.ninearchespress.com

Printed in the United Kingdom by:

Imprint Digital

digital.imprint.co.uk

Nine Arches Press is supported using public funding by the National Lottery through Arts Council England.

CONTENTS

Access Information

Introductions

Jane Commane

Khairani Barokka

Daniel Sluman

Sandra Alland

Bodies

Kuli Kohli

Abi Palmer

Claire Cunningham

El Clarke

Debjani Chatterjee

Miki Byrne

Holly Magill

Grant Tarbard

Abigail Penny

Jacqueline Pemberton

Raisa Kabir

Rules

Isha

Cath Nichols

Alec Finlay

Georgi Gill

Rose Cook

Sarah Golightley

Gram Joel Davies

Khairani Barokka

Cathy Bryant

Sandra Alland

Aaron Williamson

Maps

Raymond Antrobus:

A Language We Both Know (essay)

Abi Palmer:

No Body to Write With: Intrusion as a Manifesto for D/deaf and/or Disabled Poets (essay)

Bea Webster

Andra Simons

Gary Austin Quinn

Donna Williams

Jackie Hagan

Mark Mace Smith

Markie Burnhope

Miss Jacqui

Alison Smith

Eleanor Ward:

How can we identify a UK disability poetics? (essay)

Nuala Watt:

Insufficiently Imagined: Partial Sight in Poetics (essay)

Dreams

Rachael Boast

Daniel Sluman

Nuala Watt

Karen Hoy

Eleanor Ward

Julie McNamara

Lisa Kelly

sean burn

Naomi Woddis

Giles L. Turnbull

Emily Ingram

Clare Hill

Catherine Edmunds

Raymond Antrobus

Legends

Saradha Soobrayen

Andra Simons

Angela Readman

Rosamund McCullain

Michelle Green

Kitty Coles

Stephanie Conn

Colin Hambrook

Lydia Popowich

Joanne Limburg

Markie Burnhope

Descriptive Text of Photos and Vispo

Content Notes

Some Short Definitions for Complex Ideas:

D/deaf and Disabled Terminology

Biographies and Notes

Thank Yous

Supporters

Access Information

Audio content at this location is not currently supported for your device. It can be accessed online at bit.ly/saw1access

Audio:

Many of the poets in the anthology have kindly provided audio recordings of themselves reading their poems or essays. These, and recordings of access information, can be accessed online at Nine Arches Press’ Soundcloud address: https://soundcloud.com/ninearchespress. Relevant pieces of writing are marked with this symbol which is clickable in our e-book version, and goes directly to individual poems or essays.

Video:

Sandra Alland has curated and co-created a selection of film-poems that showcase poetry in British Sign Language and other poetry on film. In the book, film-poems are represented by a still image from each film-poem, with a URL (web address) listed beneath it; these are clickable in the e-book. All films have captions, some feature BSL, and text/transcripts of the poems appear on YouTube (in some cases these are downloadable). Some silent films also have voice-over video versions and/or Soundcloud links with audio recordings of the poems. In Stairs and Whispers, the poems are marked with these symbols:

Descriptive Text of Still Photos and Vispo (Visual Poetry):

For the cover, still photographs from film-poems, and poetry that is visual in nature (as opposed to text-based), we have provided descriptive text. Works with such text will bear the symbol:

(clickable in the e-book version) and are at the back of the book, beginning here. There is an audio version of these descriptions.

Content Notes:

We’ve done our best to try to list topics some people may wish to avoid or know about before reading. These are at the back of the book, beginning here.

D/deaf and Disabled Terminology:

Throughout the book, we use terms such as ‘D/deaf’, ‘disabled’, ‘the social model’, ‘neurodiversity’, etc. We have provided basic definitions of some concepts for those who might want such information. These are at the back of the book, beginning here.

Biographies and Notes on the Poems:

More information on the poets and their processes is at the back of the book, beginning here.

Links to all audio and video content:

In case of any links breaking or not working, you can find the main links through to all audio and video content for the Stairs and Whispers anthology here: bit.ly/stairsandwhispers

Introduction

Jane Commane

Between 2013 and 2014, conversations with two Nine Arches Press poets, Markie Burnhope and Daniel Sluman, touched upon the idea for what was initially outlined as an anthology of ‘disability poetics’. My discussion with Markie had followed the Fit to Work: Poets Against ATOS project, and ideas about what could or should follow it, whilst the latter conversation was initiated by Daniel, who identified that there was, as yet, no UK companion anthology to the ground-breaking American anthology, Beauty is a Verb.

Both ideas came together in the right moment. There seemed to be a conspicuous absence in the contemporary UK poetry landscape (and in wider literary discourse). And it wasn’t as if D/deaf and disabled poets weren’t out there; they simply weren’t being thought of, included, invited or considered. It’s a theme that the poets and editors themselves will pick up on directly and far more eloquently than I can throughout this remarkable book, so I will allow readers to explore and consider this further within the pages that follow.

The idea of this anthology grew (as all good ideas should) firm and unshakeable roots; Daniel and Markie became editors, and brought on board a third editor, Sandra Alland. Although sadly Markie stepped down from editing due to health issues in 2016, we were very fortunate that Khairani Barokka was able to join the editorial team, and bring her instincts and insight to further enrich the anthology. Under the careful stewardship of its editors, Stairs & Whispers has grown vigorously from those early, vital seedlings of ideas that began life in conversations at a crowded book fair in London and on a chilly April morning at the Wenlock Poetry Festival.

Together, the editors refined and interrogated what the ideal anthology should be, what it should (and shouldn’t) contain, who it must include, and what its terms of engagement and reference would be. The submission guidelines further made this clear – creating a manifesto for the anthology that was ambitious and deeply rooted in a politically and socially aware approach to issues that affect the everyday lives of D/deaf and disabled people.

What was clear from the outset was that the editors were determined that this would be an anthology by and for D/deaf disabled poets, which centred their voices and would be entirely directed by them. As a publisher (and non-disabled person), my contribution has been to ensure I create that space for this vital work to take place, to fund and support that work, and to ensure that the platform Nine Arches Press has as a publisher can be used to magnify and amplify the poets this book sets out to foreground.

This is especially vital in our contemporary situation, where we are witnessing the systematic dehumanisation of disabled people by the government and the state in the UK and beyond. Brutal benefits cuts and the removal of services, access and support (not to mention human rights) are brazenly coupled with deeply negative and damaging media narratives, which in turn create an atmosphere where abuse, prejudice and violence is further normalised.

Amidst this, D/deaf and disabled people are often shut out (literally and physically) and frequently spoken for, over, or about in our media and culture. Too often, their stories are taken and retold to fulfil a certain agenda. Ever more vital then, to work against this and create or open up spaces where D/deaf and disabled people can answer back – and indeed, write back – for themselves.

Dylan Thomas said that ‘a good poem helps to change the shape of the universe’. I believe that a good anthology helps to change the shape of the universe too – and not just for the poets it brings together, but the communities of poetry it plays a part in defining. A good anthology also changes the shape of things to come for communities of readers now and in the years ahead; it creates new readerships, changes plans, opens doors and alters the list of possibilities. I hope that Stairs and Whispers will be instrumental in creating new poets, showing how D/deaf and disabled poets before them have wielded the power of poetry’s distinct language of possibilities to give voice, space and page-room to the expression of human experiences.

From the beginning, the editors were also committed to ensuring that this project was as accessible, wide-ranging and diverse as possible. Their efforts speak for themselves – from known backgrounds and experiences, over three quarters of the writers in the anthology are women, over 20% are BAME, and more than a third are LGBTQ+. Also, it is notable that this anthology is representative geographically as a national survey, with poets spread regionally across Scotland, England, Wales and Northern Ireland.

Here, you will find a superb selection of poets writing with ferocity, brilliance, and humour. In recent months, as I’ve come to know the poems in this book intimately, I’ve frequently found myself returning to them and each time finding afresh a new phrasing or image that strikes me so clearly that it insists on me taking a little more time in its company. There are poems here that are piercingly honest, angry, consoling, and throughout a potent sense of precision that is keen to challenge and push at the boundaries. In addition, I love the fact that this anthology introduces me to new writing from a number of emerging poets alongside work from more established poets whose work I am already a little more familiar with. Though I know I am a little biased, I think readers will find some of the best and most vital examples of contemporary poets at work between these pages.

The editors’ and poets’ commitment to realising the full ambitions and accessibility of this book has been outstanding. Sandra Alland collated over 80 tracks of audio made by contributors, and brought together nine films (including BSL poetry). The editors also created content notes, descriptive text of images, and disabled and D/deaf definitions. In addition, they worked closely with each poet, commissioned essays, ordered the selection and put in countless hours that created this anthology’s distinct and powerful reading experience. Their endeavours result in a print and eBook anthology that is broad, welcoming, and accessible in every way that has been possible.

And this is only the beginning. The roots this book has so readily put down are now breaking new ground; I hope that successive years see Stairs and Whispers play a vital role in bringing future D/deaf and disabled poets to the foreground, and be instrumental in the building of new platforms from which they can be read or signed, heard or seen.

It has been a privilege and pleasure to have played a small part in supporting and publishing Stairs and Whispers. I am enormously proud of this bold, influential and provocative book that the editors and the poets have made together. Long may its roots reach, and long may its effects be felt.

On Living Our Poetries

Khairani Barokka

In a world obsessed with diagnostics, numerical measurements, finite pathways to recovery, and the absolute need for such recovery in a body deemed less than able, regardless of whether or not one already feels whole, or whether our conditions have cures if we identify as sick, I would prefer to describe my disability in colours, shades and nuances. The blunt trauma of being forced into one diagnosis, then another, of having my bodily and psychic sensations dismissed, diminished, mistreated and ignored, over many years, in hospitals, clinics, schools and public spaces in various countries, has sharpened my utmost regard for the tool that is poetry. It is through stanza that communion happens between the shades of life that we all know can’t be enumerated, can’t be delineated, can’t be kept hidden from ourselves – despite how ignorance about our varied, glorious bodies and minds perpetuates systemic violence and forced disconnection, even from our own experiences.

Lack of access to healthcare in the past means my conditions of extreme chronic pain and fatigue, and other symptoms over my chest and right side, are very much socially-imposed disablements. ‘Disabled’, as we all (should) know, is the opposite of ‘enabled’, not ‘unable’, and I was left unenabled, to suffer unnecessarily for years, for a number of reasons that have become clear in hindsight.

Because I was brown and a woman, because women’s pain of many kinds is known to be underestimated and undertreated, because I lived in Brooklyn in an area where nearby hospitals served other brown folks, communities of colour, in circumstances that still leave me aghast in memory. Because I lived in and come from a country, Indonesia, attempting to recover from hundreds of years of colonialist resource extraction, then a dictatorship and mass murder, where neurologically-complex care and mental healthcare are precious and rarely done well. Where communities are fighting not to fray under socioenvironmental ills, and disabled girls generally don’t end up this lucky – I have loved ones, and over the years they have learned that although I didn’t expect my physique to feel this way years ago, I am stubborn as hell, and demand nothing less than absolute love for a body that’s taken more than its share. That all of us are more than the sum of our parts. Neglect has meant I am taking longer to understand coping mechanisms, but this body is not somehow incomplete or lacking because it is internally different from an ‘abled’ prior state. It is showing its strength and persistence. It exists fully in the now, not in an alternate universe as ‘more able’. As a relatively recent transplant to the UK, I am deeply grateful for the opportunity to recognise those in our communities as always fully present in this way, through literature, and to understand how each of us conveys differently our varied experiences here.

The situation for disabled communities in Indonesia, and other countries with less access to accessibility and healthcare resources, is infinitely worse than in the UK, but the UK has indelible complicity in this lack, as do other Western countries: countries and communities are not ‘developing’ but underdeveloped, as a result of legacies of brutal resource transfer, slavery, governments installed by other governments to ‘stabilise’ and also to oppress. Within the UK, resources flow towards some and not others. Bleeding rural communities of resources breeds disablement within those communities, as does treating immigrants and refugees as criminals, denying the need for bodies and lives to be honoured, in our infinite variety, in our various likelihoods of survival, in our universal need to form community and to be treated as human. When D/deaf and disabled communities are doubted, criminalised as benefit scroungers, and simultaneously pitied, an upswell of resistance demands attention, and so too does poetry reflecting our emotions in this climate demand to be read.

It’s been just over a year since I was finally prescribed medicine I should have been given at least five years before, if the innumerable healthcare providers I saw had offered a proper pathway towards holistic pain management. And before that, there were other stories I am continuing to work through, primarily in one way: throughout the years, my salvation has been the innate desire to read to and to contribute to the world of poetry in many forms, where the transformation of emotion into language and back seemed and continues to seem iridescent, a work of magic when done well. Though not all first-person poems I’ve written are autobiographical, nor are those of others, and not all poetry is written in first-person perspective, through it we go beyond appreciation of our inner selves, and inhabit, momentarily, other lived experiences.

Questioned as to whether my pains are real until I am in a situation where I can no longer visually ‘pass’ for abled, poetry is a conduit for both illumination and mystery. Through poetry, I can be both in pain and doing well (including as I write these words), an intellect and carnal, a fabulist and a memoirist, a Muslim feminist who grew up knowing that binaries are false and rarely kind in implementation – both suffering from and struggling through physical pain, and fiercely proud of being disabled, as a much-misunderstood and greatly-varied denomination.

Poetry is where I have attempted to translate between disabled and non-disabled worlds, but my work is most at home with D/deaf, disabled and crip compatriots. I’m grateful for the opportunity to have joined the editorial team of Stairs and Whispers, and it has been such an honour to be amongst these poets, in shared understanding of the liminal nature of being in a body, in shared release of exhaustive misunderstandings and hurts, slights and continual expectations of speaking on behalf of all of our kind, and also expectations of speaking in tongues the abled can relate to. This, however, is for us. To laugh and weep within, to be still and to be angry alongside. It has been such a joy to play with language with my co-editors and with these contributors, in dialogue, in solidarity, as indeed we all write back.

shove ten pounds of sugar in a seven pound bag

Daniel Sluman

the poem is an artefact

made from words

& the space that exists

between & around the words

the spaces

are the negative of the words

part of a reciprocal

dialectic relationship

with the words

( without the spaces

there are no words )

*

i am human

the shape of my body

exists within space

there are gaps & absences

within & around my body

every human has a unique set

of absences created by their body

( without the absences

there is no body )

*

my absences

are perhaps more apparent

than other people’s

i have an absence

where my left leg should be

as a reader / passer-by

you will notice the absence

of my left leg

the absence

will be more powerful

than if my leg was there

( shove ten pounds of sugar

in a seven-pound bag )

*

the absence forces you

to ascribe meaning to it

forces you to project

your own emotional /

intellectual self

within the absence

( mommy why has that man’s leg

fallen off ? )

i am a walking signifier

*

the page is a canvas

screen

stage

the poet reflects

( disassembles )

themselves

on the page

each space is apt

each word is placed

like ice in water

as a crippled writer

you can put your body

into the poem

with all its faults

scars

gaps

they’ll dry like ink

from the damp notation

of your self

*

the disabled writer

turns the page

into a mirror

reflecting the reader’s

own mortality their fears

nightmares the i couldn’t live like that

we are on the fine end of a wedge

we can see aspects of societal behaviour

which they may not (wish to)

see themselves

a dead russian writer once said

that all good writing

is defamiliarisation

that all good writing

will get to the heart of an object / concept

( make the stone

stony again )

& turn it into art

disability defamiliarises life

forces you to question

could i do that ?

*

bonecancer at 11

& the disarticulation of a limb

has been a blessing

i would thank in prayer

every day if i believed god

was listening because

i know all this

immediate noise & fizz

is bunk / nothing / zero

& i would not be who

i am now without

that wonderful magic trick

see his leg has disappeared !

a trick so real

no one stands to applaud

bit.ly/saw2shove

Nothing About Us Without Us, No One Left Behind

Sandra Alland

Writing *to* disabled people has all sorts of implications, not just topic and diction but orientation, the things you don’t explain but just let float out there. When I consciously undertook writing poems with a crip audience in mind, I let go of the myth of universality.

– Jim Ferris, Poetry magazine, 2014

We cannot comprehend ableism without grasping its interrelations with heteropatriarchy, white supremacy, colonialism and capitalism. Each system benefits from extracting profits and status from the subjugated ‘other’.

– Patty Berne, Skin, Tooth, and Bone – The Basis of Movement is Our People: A Disability Justice Primer, Sins Invalid, 2016

Writing to Disabled, Crip and/or D/deaf Communities

In 2014, I was approached by Markie Burnhope, Daniel Sluman and Nine Arches editor, Jane Commane, to be co-editor of an anthology of disabled and D/deaf poets. Markie, Daniel and I began a beautiful conversation about what it means to be a disabled writer, and what disability poetics is and isn’t, and hasn’t yet become. Sadly, Markie left the editorial team because of health issues, but she has remained a vital part of the project. In 2016, Daniel and I continued and reshaped our conversations with a brilliant new co-editor, Khairani Barokka. Together we three selected poems and moulded them into a book.

From the get-go it was clear that many non-disabled people would immediately frame ‘disability’ as something specific in their minds, and that even some disabled people might have internalised non-disabled and hearing ideas about disabled and D/deaf identities, experiences, cultures – and poetry.

We made it clear in our call-out that the book was not for writing about our communities, but writing by our communities. The non-disabled people who objected to this and wanted to be published were few, but yes, it happened, and yes, those people felt entitled to proclaim their right to our spaces and stories. Dismantling ableism and privilege is a long process indeed.

In the call-out, written by Markie, Daniel and me, we attempted to define disability as broadly as possible, not based on narrow assumptions and medicalised notions of ‘impairment’, and moving towards intersectional ideas of disability justice in a UK1 framework:

We plan to draw on the context of anti-Atos/Welfare Reform and NHS privatisation activism, whose leading lights (particularly on online social networks) have been women, including trans women, queer women and/or women of colour – a clear antithesis to the systemic norm. In both poetry and prose we plan to explore, creatively and critically, other bodily identities and oppressions that intersect with disability to create what poet and activist Eli Clare called ‘marked bodies’. Racialised bodies, gender non-conforming bodies, bodies ‘marked’ by class or religion.

As editors we are committed to the social model of disability (with contributions from other radical socio-political models), which means we are casting a wide net in our call for poets who self-identify as disabled, people with disabilities, crip, D/deaf, or any variation thereof, and who may consider their impairments and/or their disabled or D/deaf identity a key part of their thematic, conceptual and aesthetic practice… We also aim to include D/deaf writers/performers who do not identify as disabled…

I was over the moon at the possibility of helping bring into the (UK) world something as important as a collected work by disabled and D/deaf poets; in fact it made me a bit weepy. Why? Because I know thousands of brilliant, innovative and talented disabled, D/deaf and/or crip writers, artists, filmmakers, musicians and performers – but most non-disabled people would struggle to name one of them.

At this moment in time (and place), writers and performers from our communities are particularly absent from the main stage. The primary reason is the same old reason, and overlaps with the reasons all marginalised people are absent – people who are trans, gender diverse, black, racialised, queer, working class and/or from other marginalised groups are all familiar with being left out of the publishing, performance and promotion of literature. It’s plain old oppression in a white supremacist, classist, heterosexist, cissexist, (trans)misogynist and ableist world.

Non-disabled people are generally not interested in our stories, unless of course they’re telling them. Unless our bodies and minds are performing the struggle of the noble, pitiable crip, or the deformed villain whose evil manifests itself in disability, or the supercrip who overcomes their disability to attain a place in the ‘normal’ world (often by engaging in a cis/hetero- and romance-normative relationship). Unless we act as foils for the development of a non-disabled character. Unless we are so very grateful.

And sometimes, unless we are otherwise acceptable as white and middle class.

Our absence as disabled and D/deaf people in some ways also has to do with writing communities in the United Kingdom being arguably somewhat behind the United States2