22,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The Crowood Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

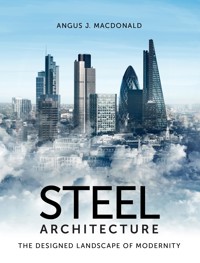

Steel Architecture offers a re-interpretation of Modernist design through an examination of the history of metal-framed buildings, from the mills, warehouses and spectacular glasshouses of the nineteenth century to the multi-form, tall towers which currently characterize the skylines of the world's major cities. Based on extensive research, this insightful book reassesses the development of a signature landscape of Modernism through the lens of contemporary issues, and critically appraises some of the most prominent works of architecture of the Modern age, including Mies van der Rohe's Barcelona Pavilion, Richard Neutra's Lovell Health House, and Frank Gehry's Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao. Topics covered include: the early commercial steel buildings; steel and mid twentieth-century consumerism; the Chicago skyscrapers of the 1970s; High Tech architecture and finally the 'formalist' architecture of the late-Modern period. Extensively illustrated and accessibly written, Steel Architecture discusses the meanings behind the visual vocabulary of Modern steel architecture, and places the style in the broad context of the social, political and economic preoccupations of its age.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 354

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

STEEL

ARCHITECTURE

THE DESIGNED LANDSCAPE OF MODERNITY

ANGUS J. MACDONALD

STEEL

ARCHITECTURE

THE DESIGNED LANDSCAPE OF MODERNITY

First published in 2021 byThe Crowood Press LtdRamsbury, MarlboroughWiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2021

© Angus J. Macdonald 2021

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication DataA catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 966 2

Cover design: Sergey Tsvetkov

Contents

Preface

Chapter One Steel Architecture in Context

Chapter Two Steel Comes to Architecture

Chapter Three Early Steel Commercial Buildings

Chapter Four Steel and Early Modernism

Chapter Five Steel, Glass and Discipline

Chapter Six Steel and the Consumer

Chapter Seven The Skyscraper

Chapter Eight High Tech

Chapter Nine Recent Steel Architecture

Chapter Ten Steel and the Demise of Modernism

Bibliography

Notes

Index

Acknowledgements

Angus Macdonald would like to thank all those involved in the inception and production of this book: most especially his colleagues and students at the University of Edinburgh for useful and interesting conversations, particularly the members of his long-running Honours Course ‘Structure and Architecture’, in the joint degree ‘Structural Engineering with Architecture’; all those who have kindly provided quotations, and the wide range of photographs and drawings that illustrate the text; as well as the staff of The Crowood Press for their patient and unfailing assistance.

He would also like to express very grateful thanks to his wife and professional partner, Dr Patricia Macdonald, for her continuous support throughout the making of the book, and in particular for her thoughtful, thorough and expert assistance with the text and illustrations.

Preface

Steel Architecture: A Barometer of the Modern Condition

Steel buildings have encapsulated most aspects of Modernist culture, from the positive, aspirational visions of an exciting and rewarding lifestyle, expressed architecturally in pristine metal-and-glass buildings, to the negative realities of the Modernist industrial-capitalist complex: monotonous, de-humanizing buildings and townscapes that lead to alienation; excessive wealth inequality that weakens the fabric of society; and over-consumption of resources that is a major cause of pollution, biodiversity loss and climate breakdown on a planetary scale. This book seeks to present a balanced account of the relationship between steel architecture and Modernist ideas.

At the beginning of the Modern period, steel-framed buildings were prominent in the quest by architects for new forms of visual expression. The dematerialization of form and open-planning of Mies van der Rohe’s Barcelona Pavilion of 1929 captured something of the new cosmology of the post-Einstein universe; the Glass and Farnsworth Houses of the 1950s presented a vision of an appropriate domestic environment for the truly Modern individual; the Eames (1949) and Stahl (1960) Houses envisaged a closer relationship between humans and the industrial hinterland of Modernity through the use of mass-produced components in an unmodified state; the Centre Pompidou (1977) explored how the resources of major industries could be used to create a Modern temple of culture that was democratically accessible; and the skyscraper speaks clearly of a world of wealth accumulation, inequality and globalized corporate governance.

Steel architecture has, throughout its history, projected its message without irony, and recently, in denial of its global environmental consequences. The latter position has been most clearly demonstrated in such buildings as the CCTV headquarters in Beijing (2009), and in claims like that made for the Bloomberg European headquarters in London (2017): that it represents a vision of the office of the future.

This book reappraises the role of steel architecture in creating a built environment that is both a response to and an expression of the Modern condition. It seeks to place steel architecture in its proper context, to assess what exactly was achieved by it and to question what its role might be in the post-Covid-19 world of climate and ecological emergencies.

Angus J. MacdonaldJanuary 2021

Chapter One

Steel Architecture in Context

Introduction

The architecture of steel and glass has been described as the ‘signature landscape of Modernity’,1 a highly perceptive observation because it was the technology of steel that produced the Modern world of cities, industry and mass transport. The steel-framed skyscraper, with its symbolism of domination and control, was perhaps the most potent of the building forms that Modern architecture produced, and this was, and remains, fitting, both literally and metaphorically, because, of all the enabling materials of the Modern lifestyle, steel is one of the most fundamental.

Fig. 1.1 City of London finance district: steel-framed skyscrapers – the signature landscape of Modernity. Fantasy or reality? (Photo: Tim Robberts/Getty Images)

Fig. 1.2 Seagram Building, New York, 1958; Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, architect; Severud Associates, structural engineers. The ultimate Modernist skyscraper – a minimalist cage of steel wrapped in a thin covering of glass and bronze. (Photo: NYC Urbanism LLC)

Without a material with the unique physical properties of steel – its very high strength combined with toughness and ductility, and an internal structure that allows its properties to be varied by the inclusion of trace elements and modified by heat treatment – the Modern world would not exist in its present form. It was the enormous strength of steel that allowed the construction of structures and buildings of wide span or very great height, and the creation of the aesthetics of the Modern interior of spidery-framed chairs and tables with thin legs and glass tops.

Steel has been used for myriad components, essential for Modern living, that must at the same time be very strong and of compact scale, such as working parts for engines, wheels for motor cars and railway locomotives, posts for street lighting, barriers for motorways, radiators for central heating – the list is almost endless; the infrastructures of major industrial installations – for example petrochemical works – are made from steel as are the tankers that transport crude oil and the pylons from which electricity transmission cables are suspended. The ductility of steel allows it to be bent into the shapes of car bodies and the outer skins of ‘white goods’ domestic appliances; its hardness allows it to function as cutting tools – from the blades of combined harvesters to files for smoothing metal to kitchen knives for cutting vegetables – with edges that do not become blunted with use. Steel is one of the essential enablers of the Modern lifestyle.

This book explores the development of steel architecture in the Modern period, from its origins in the nineteenth century to the present day, and discusses both its importance as a building typology and its significance as an image in the world of architecture and design. It also examines the relationship of the steel building to the social, political and economic preoccupations of its time.

It will be important to bear in mind, however, that the steel-frame building is actually only one of the most recent iron-based artefacts that have been significant in the history of civilization. Seen against the broad sweep of historical time, the Modern age of steel has been relatively short and is in fact likely, in its present form, to be nearing its end as a consequence of the adverse effects of human-induced changes to the ecologies of the planet, including anthropogenic climate change – a phenomenon that steelmaking has helped to bring about.

An additional purpose of the book is to enable the steel building to be perceived not as one of the culminations of the human use of ferrous metal that should be treasured and celebrated as such – as is often implied in writings on Modernist architectural history – but simply as an artefact that was important for a relatively short period in the very long history of the relationship between humans, ferrous metals and the global environment of which they form part and that may, in its present form, be coming to an end.

Ferrous Metals in Human Civilizations

In his book Guns, Germs and Steel: A Short History of Everybody for the Last 13,000 Years (1997), Jared Diamond explored the question of why it has been that in the 13,000 years or so in which humans have lived in highly structured societies, some of those societies continued throughout to use artefacts of stone and wood while others developed complex metal-based technologies that enabled the lifestyles of the techno-societies that dominate the world in the present day. In the twenty or so years since its publication, Diamond’s penetrating survey has acquired increasing significance as humanity faces the prospect of having to deal with the consequences of the resulting overexploitation of the world’s resources.

Diamond drew attention to the fact that it was the discoveries and inventions associated with metalworking that were crucial to the development of sophisticated technologies, and noted that this occurred, in varying degrees and at varying rates, throughout the ‘Old’ World, from China and Japan in the east, through Asia and Eurasia, and including sub-Saharan Africa. The ‘three-age timeline’ into which archaeologists subdivide the prehistory of Europe (the Stone, Bronze and Iron Ages) reflects the influence of metalworking on societal development. The move from hunter-gathering to settled farming, and subsequent developments in agriculture that released large sections of population from the need to be concerned with food production and allowed them to become involved with other activity, was a necessary phenomenon that enabled the development of metallurgical techniques. Diamond pointed out that the forms of the various social and political structures that facilitated metal production emerged differently in different parts of the world but that it was in Europe that the particular combination of circumstances that gave rise to the Modern world occurred.

Although metal artefacts were used for a wide variety of purposes, it was their employment as weaponry and tools that had the greatest effect on the societies that produced them and it was the ability of ferrous metallurgy to provide more effective weapons and tools than those of bronze that caused the transition from the Bronze to the Iron Age. The crucial ferrous metal was in fact steel – a complex solid based on a mixture of iron and carbon, as solid solution, chemical compound and, in some cases, as crystals of pure iron. Its production involved the reduction of iron by smelting in basic furnaces called bloomeries and a subsequent process of laborious hammering and annealing to further eliminate impurities and refine the metal to the low carbon content required for steel (0.15 to 1.5 per cent). The processes were known throughout most of the ‘Old’ World by around 500 BCE and often involved a degree of mechanization in the form of water-powered bellows (to raise the temperature of iron furnaces) and tilt hammers for the steelmaking process.

Wootz steel, distinguished by a pattern of thin layers of various ferrous and carbon material produced by the laborious refining process that involved both rolling and hammering, was being made in India from the sixth century BCE and was exported as ingots throughout the Ancient world, most particularly to the Levant where it was worked to form the highly prized Damascus steel blades that were notable for their combination of flexibility and hardness. Iron and steel products, in various states of manufacture, were widely traded throughout the Ancient world and the renowned ‘quinquereme of Nineveh’ was just as likely to have been carrying ‘ironware’ in its hold as any ‘dirty British coaster’2 of the twentieth century. By the late medieval period, types of ‘Damascus’ steel were being made in many locations, one of its main applications being in the manufacture of barrels for early firearms.

Ancestors of the blast furnace – the present-day plant in which iron ore is smelted – are thought to have been in use in China in the first century CE. The oldest known examples in Europe date from the thirteenth century CE and by the fifteenth century their use had become widespread, probably in connection with casting of cannon. It is likely that the various processes required for the refinement and working of iron were in fact independently invented throughout the ‘Old’ World over a long period.

As was surveyed by Diamond, the sequence of historical events that took place throughout the world in the thousand or so years that separated the end of the Iron Age (around 600 to 800 CE) from the first indications of the Modern world were many, varied and diverse. They resulted in the peculiar concentration of wealth and military power in Northern Europe that gave birth to the first Industrial Revolution: military power was ‘necessary’ so that lands could be conquered and colonized and their resources ‘released’; wealth was required to fund both the exploratory expeditions that made world resources available to Europe and the various industrial and commercial enterprises that made use of them.

Steel played an essential role in all of this. Although the factors that gave rise to the first Industrial Revolution in Europe were highly diverse, they could not have functioned without the superior weaponry and tools that steel made possible. Steel was not just one of the most vital metals of the Modern world, it was highly instrumental in creating the conditions that made it possible.

The Second Iron Age

The Modern era of iron and steelmaking began in the early eighteenth century with the invention of techniques that allowed iron ore to be smelted on an industrial scale. The crucial development was the substitution of coke for charcoal as the fuel in the smelting process. Coke was both cheaper than charcoal and enabled furnace temperatures capable of actually melting the iron. Ironmaking on an industrial scale was first developed in Coalbrookdale in England where the Darby family of ironmasters introduced techniques of smelting iron ore with coke in blast furnaces equipped with water-powered bellows that delivered hot blasts of air through the molten iron to produce pig iron (a form of cast iron). The ironmasters of Shropshire made a large range of products, including components for buildings as well as a wide variety of domestic, industrial and agricultural appliances. Their most notable construction was the iron bridge across the River Severn at Coalbrookdale – the world’s first major structure of the industrial age to be made entirely of iron.

Fig. 1.3 Coalbrookdale by Night (1801); Philip James de Loutherbourg. This famous painting of the Madeley Wood iron furnaces at Coalbrookdale epitomizes the early stages of the production of iron on an industrial scale. (Image: Science Museum, London/Wikimedia Commons/public domain)

Fig. 1.4 The Iron Bridge, Coalbrookdale, England, 1779; Thomas Farnolls Pritchard, architect; John Wilkinson, ironmaster. The bridge at Coalbrookdale was the first major structure of the Modern age to be constructed entirely from cast iron. (Photo: Tk420/Wikimedia Commons)

The Coalbrookdale bridge demonstrated well the useful properties of cast iron. The first was its superior strength, in comparison to timber or stone, that allowed the bridge to be composed of a filigree of delicately slender arches that contrasted with the massive stone arches of earlier bridge technology. Second was the casting process itself, that enabled relatively complex forms to be produced with ease. These two properties were rapidly exploited by builders to produce the beams with I-shaped cross-sections and the circular hollow columns of early industrial buildings. Disadvantages of cast iron were its brittleness (that made it unreliable in tension and could lead to sudden and catastrophic structural failure) and the casting process itself, that could result in the incorporation of impurities (that might be simply bubbles of air) that would weaken the castings.

The next significant development in the industrialization of iron metallurgy involved improved methods for the refinement of pig iron into wrought iron – chemically pure iron and a material whose mechanical properties were greatly superior to those of cast iron – in a ‘puddling’ process invented by Henry Cort (1740–1800), who was also instrumental in developing the rolling process for shaping the iron into useful components, such as the angle and the channel structural sections.

Fig. 1.5 Detail, the Iron Bridge, Coalbrookdale, England, 1779; Thomas Farnolls Pritchard, architect; John Wilkinson, ironmaster. The strength of iron allows slender elements; casting facilitates complexity; mortice joints, tightened by wedges, derive from timber technology. (Photo: Colin/Wikimedia Commons)

Fig. 1.6 Train shed at Euston Station, London, 1837; Philip Hardwick, architect; Charles Fox, structural engineer; William Cubitt, contractor. The roof of this very early railway terminal is supported on delicate triangulated trusses in wrought iron, carried on colonnades of cast-iron beams (configured as arches) and columns. (Illustration: Aquatint, 1837; T. T. Bury, artist; J. Harris, engraver; from The London and Birmingham Railroad, Ackermann, London/Wikimedia Commons/public domain)

Fig. 1.7 Britannia Tubular Bridge, Anglesey, Wales, 1850; Robert Stephenson and William Fairbairn, engineers. The principal structural elements of this revolutionary design were massive rectangular tubes constructed in wrought iron. (Photo: Albumen print (c. 1860) from the Marjorie and Leonard Vernon Collection/courtesy, Los Angeles County Museum of Art/Wikimedia Commons/public domain)

Wrought iron was tough and ductile and therefore more reliable than cast iron and this allowed it to be used safely in structural forms that involved tension elements and tensile connections such as long-span triangulated trusses. Some of the most spectacular civil engineering achievements of the first wave of railway building were carried out in wrought iron (Figs 1.6 and 1.7).

The industrial manufacture of steel began in the mid-nineteenth century with the invention of the Bessemer process in the 1850s. Steel has superior mechanical properties to both cast and wrought iron: it is stronger than either; it is ductile, which makes it a reliable structural material not prone to sudden failure; and, due to its unique metallurgy, it could have its properties modified in various ways through minor variations in its chemical composition and also by heat treatment. Steel could be shaped by the rolling process, which enabled a large range of useful types of element to be manufactured, and also by casting (which wrought iron could not), and it could be joined by welding and finished by machining. It was, and remains, the ferrous metal of the Modern age.

As the Industrial Revolution gathered pace from the late eighteenth century onwards, these ‘new’ versions of the ferrous metals, that had become cheaply available in large quantities due to large-scale manufacture, were quickly employed in the construction of the new types of buildings and the infrastructure that was required for the new age of commerce and industry. It also enabled an expanded lifestyle that involved rapid transport overland, on railways and across oceans in metal-hulled steamships.

Steel and Buildings

The use of ferrous metal as a major component of buildings began in the late eighteenth century when cast iron replaced timber as the favoured material for the structures of the framed buildings, free from internal walls, that were required for mills and warehouses. Innovative canal builders, such as Thomas Telford, used troughed beams of cast iron to replace traditional masonry arches in major structures such as aqueducts. The availability of wrought iron from the early nineteenth century was also exploited for the major buildings and infrastructure in the first age of railway building that occurred in the 1840s and 1850s.

Fig. 1.8 Pontcysyllte Aqueduct, Wales, 1805; Thomas Telford and William Jessop, engineers; William Hazledine, ironfounder. One of the first major civil engineering uses of cast iron, the canal is carried in a series of cast-iron troughs and arched ribs. (Photo: Tanya Dedyukhina/Wikimedia Commons)

Fig. 1.9 Palm House, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, London, 1848; Richard Turner, ironfounder; Decimus and Nicole Burton, architects. A spectacular early use of wrought-iron arches in glasshouse design. (Photo: Deror_avi/Wikimedia Commons)

In a parallel development, iron also replaced wood for the structural components of horticultural glasshouses. Richard Turner (1798–1881) (with architects Decimus Burton (1800–81) and Nicole Burton), one of the foremost ironmasters of the nineteenth century, was responsible for the spectacular Palm House at Kew Gardens in London in which the principal structural elements were arches of wrought iron. The greatest innovator in this field was Joseph Paxton (1803–65): he recognized the potential of cast iron not only as a material that (due to its superior strength) could produce frameworks with more slender elements than timber; he used it, through techniques of industrial mass production, to create a range of cheap, mass-produced, small-scale glasshouses.

Paxton’s greatest achievement was the Crystal Palace in London, created to house the Great Exhibition of 1851, which was intended to demonstrate to the world the pre-eminence of Great Britain and its Empire as the leading industrial nation. As is discussed in Chapter 2, the Crystal Palace was the most spectacular early example of a building typology that ferrous metal contributed to architecture – the glass-clad framework – in which a lightweight envelope of thin metal or glass was supported on a slender metal skeleton – one of the most potent images of Modern architecture.

Fig. 1.10 Crystal Palace, London, 1851; Joseph Paxton, designer; William Cubitt, contractor; Fox, Henderson & Co., ironwork contractors. This building was essentially a work of pure engineering in which technical considerations had to be prioritized to create an enclosure of cathedral-like dimensions that could be constructed in under a year. It was accomplished by the repetition of standardized cast-iron and plate-glass components on a modular system. The creation of one of the most important imageries of architectural Modernism – that of the glass-clad framework – was an unintended consequence. (Image: The Transept from the Grand Entrance, from Souvenir of the Great Exhibition, Ackerman, 1851; J. McNeven/Wikimedia Commons)

Fig. 1.11 Train shed, St Pancras Station, London, 1868; William Henry Barlow and Rowland Mason Ordish, engineers. With a span of 73m (240ft) these wrought-iron, trussed arches were the largest in the world when constructed. Similar railway terminals had appeared in many capital cities by the mid-nineteenth century and were highly visible examples of an entirely new building typology. (Photo: Maxiiie/Wikimedia Commons)

Fig. 1.12 Selfridges department store, London, 1909; Daniel Burnam with Francis Swales, R. Frank Atkinson and Thomas Tait, architects; Sven Bylander, structural engineer. This building is based on a steel-frame structure, as is evident from the widely spaced columns of its façade and its open-plan interior. The neoclassical treatment throughout was deemed necessary at the time for buildings that were in prominent situations. (Photo: Love Art Nouveau/Wikimedia Commons)

Fig. 1.13 Royal Insurance Building, Liverpool, UK, 1903; James F. Doyle, architect. This was one of the earliest buildings in the UK to be based on a steel framework structure. The architectural treatment is neo-Baroque. (Engraving: James Francis Doyle/Academy Architecture 1896/https://archive.org/details/academyarchitect09unse/page/n49/mode/2up/Getty Research Library/Wikimedia Commons)

By relieving walls of any structural function, metal frameworks enabled the creation of buildings with open-plan interiors and greatly extended the possibilities for the architectural treatment of their façades. The earliest of these buildings were the mills and railway stations of the first industrial age, which were strictly functional with little architectural embellishment or pretension. The usefulness of the metal framework structure was nevertheless such that it resulted in its adoption for other new types of building – for example, offices and department stores – which, due to their location in city centres, were required also to have architectural qualities. From the middle years of the nineteenth century, in an age of architectural revivalism, commercial buildings with open-plan interiors, facilitated by metal framework structures, appeared in capital cities and the high streets of industrial towns, masquerading as Greek and Roman temples, Venetian or Florentine palaces, and medieval-Gothic town halls. By the beginning of the twentieth century steel had become established as the principal structural material for large-scale buildings of this type, prominent examples in the UK being Selfridges department store in London (1909) and the Royal Insurance Building in Liverpool (1903) (Figs 1.12 and 1.13).

Fig. 1.14 Guaranty (Prudential) Building, Buffalo, New York, 1896; Louis H. Sullivan and Dankmar Adler, architects. Despite his insistence on generous levels of ornamentation, Sullivan is regarded as a precursor of Modernism in architecture. His distinctive and original style acknowledges the existence of the steel framework that supports the building. (Photo: Jack E. Boucher/Historic American Buildings Survey/Wikimedia Commons/public domain)

It is notable that the contribution that the steel frameworks made to these buildings was not acknowledged aesthetically. The steel columns in the interior of the Selfridges store, for example, were encased in classical ornamentation of wood and plaster in a neoclassical scheme of interior decoration that took its themes from an earlier age of building technology, as did the elaborate Baroque-style masonry in which the Royal Insurance building was clad.

Steel and Architecture

The development of a style and vocabulary of architecture that acknowledged visually the importance of the metal frame as a fundamental part of the building occurred in the US, the pioneering architects being William Le Baron Jenny (1832–1907), Louis Sullivan (1856–1924) and Dankmar Adler (1844–1900). One of the key building types was the multi-storey office building and that led, as is discussed in Chapter 3, to the invention of a new building type – the skyscraper – and an approach to the styling of tall buildings that anticipated the Modern architecture of the twentieth century (seeChapter 7).

Fig. 1.15 John Hancock Center, Chicago, 1969; Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, architects and structural engineers. One of the third generation of American skyscrapers, the architectural concept of this building is entirely Modern. A trussed-tube structure was adopted to provide adequate lateral strength and forms a major component of the visual vocabulary. (Photo: Ken Lund/John Hancock Center/Wikimedia Commons)

The first of the truly Modernist skyscrapers was the Seagram Building in New York (1958) (Fig. 1.2) by the architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe (1886–1969), and this was followed by a whole series of icons of Modernism in the 1960s and 1970s that included the twin towers of the World Trade Center in New York (1973) (Fig. 7.21), and the John Hancock Center (1969) (Fig. 1.15) and Sears (Willis) (1973) buildings in Chicago (Fig. 7.23).

Although the use of a steel framework as the structural armature for a skyscraper was fully justified on purely technical grounds, because a structure of exceptional strength was required, no such argument could be made for a building of domestic scale. Function and aesthetics may have been united in the Seagram Building but no such fusion of intentions could be claimed for Mies’s near-contemporary Farnsworth House (1951) (Fig. 1.16), which is perhaps the purest example of the use of a steel framework as a visual element in Modern architecture and represents steel at its least functional and most stylistic. The fetishization of steel in the cause of the promotion of a Modern aesthetic agenda found its most explicit application in the British High Tech movement of the 1970s and 1980s, with buildings such as the Centre Pompidou in Paris (Fig. 8.7) and the headquarters of the Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation in Hong Kong (Fig. 8.1), in which the purely functional aspects of the structural design were frequently compromised to accommodate a predetermined aesthetic agenda.

Fig. 1.16 Farnsworth House, Illinois, 1951; Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, architect; Myron Goldsmith, structural engineer. This is the ultimate minimalist Modern architecture in steel and glass. (Photo: Victor Grigas/Wikimedia Commons)

Fig. 1.17 Dubai, United Arab Emirates. Dubai now has more buildings higher than 670m (2,200ft) than any other city. Although many of the latest skyscrapers are based on reinforced-concrete structures, the development of the skyscraper typology, that has been responsible for the distinctive skylines of all major cities throughout the world, was largely due to the technology of the steel framework. (Photo: Time Out)

Frameworks of structural steel have also played an essential and vital role in the explosion of high-rise building activity that has resulted from the property development boom, fuelled by venture capital, that has characterized the opening decades of the twenty-first century in most of the major cities of the world, although the winner of the accolade for the world’s tallest building has been, for many years, the Burj Khalifa in Dubai, that was, ironically, based principally on a reinforced-concrete structure.

Steel and the Environment

With the increasing realization of the very serious environmental consequences of the activities of the capitalist-led Modern economies of the first two decades of the twenty-first century, the aspirations of the minority of wealth owners who finance major building projects have come into serious conflict with the interests of the majority of the inhabitants of the planet due to the effects that such developments have on environmental degradation and climate change. Although attitudes may swiftly change in the near future, the principal effect of these concerns on building activity has been largely cosmetic and superficial. When the building at 30 St Mary Axe (‘The Gherkin’) in London (Fig. 1.18) was completed in 2004 it was claimed that it was London’s first eco tall building. Similar claims were made of the Bloomberg headquarters building in London when it was completed in 2017. Both are based on steel framework structures that facilitate their distinctive architectural features but that incur considerable environmental costs. The sustainability credentials of these two buildings have therefore been very seriously questioned.

Fig. 1.18 30 St Mary Axe (‘The Gherkin’), London, 2004; Foster + Partners, architects; Ove Arup & Partners, engineers. ‘London’s first ecological tall building’ was the claim made by the architects for this building, based on the ‘green’ operational features which were incorporated. The embodied energy of its materials, including its steel framework structure, cast doubt on its ecological credentials. (Photo: CEphoto, Uwe Aranas/Wikimedia Commons)

Fig. 1.19 Bloomberg European headquarters, London, 2017; Foster + Partners, architects; AKT 11, structural engineers. This building is packed with high tech systems and devices that facilitate all aspects of its operation including the management of its energy consumption and waste disposal. The high embodied energy of its steel framework and high-quality finishes nevertheless detract from its overall environmental performance. (Photo: The wub/Wikimedia Commons)

Fig. 1.20 22 Bishopsgate, London, 2020; PLP Architecture, architects. Nicknamed ‘The Wodge’ and seen here alongside ‘The Cheesegrater’, 22 Bishopsgate is the largest steel-frame office development in London with 121,000 square metres (1.3 million square feet) of lettable office space. A product of the stretching of loose planning rules and of property speculation fuelled by spectacular rises in land values, it could be the last of its kind in a post-Covid-19 world of homeworking and climate emergency. (Photo: Robert Evans/Alamy Stock Photo)

The largest single office development in London is the steel-frame building at 22 Bishopsgate, nicknamed ‘The Wodge’ and completed in 2020. It has been described as ‘the absurdist conclusion of three decades of steroidal growth, the final product of superheated land values and stretching loose planning laws to breaking point.’3 It too may be one of the last of its kind as the post-Covid-19 world is forced to adjust lifestyles and working practices in the context of the current climate emergency.

Steel frameworks have also played a significant role in the creation of the fantastical forms of building types that have been popular in recent decades, such as the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao (1997) (Fig. 9.1) and the Imperial War Museum North in Manchester, England (2002) (Fig. 9.7).

Conclusion

The steel framework therefore remains for the present an essential typology of Modern building. For how long this will continue is a matter of conjecture as it seems increasingly probable that it may represent the swansong of a building technology that, functionally and symbolically, represents a particular phase only of the history of the evolution of human societies on planet Earth – and a relatively short phase at that – one that lasted for just over a single century in a relationship between humans and ferrous metals that spanned more than three millennia, and which constitutes the broad context against which the significance of steel architecture should be judged.

Chapter Two

Steel Comes to Architecture

From the Enhancement of Traditional Forms through Ferro-Vitreous Art to the Invention of a Modern Aesthetic

Introduction: The Invention of a Modern Aesthetic

The twentieth-century structural engineer Edmund (Ted) Happold (1930–96), founder of the firm Buro Happold, president of the UK Institution of Structural Engineers and leader of the team of engineers from Ove Arup & Partners that was responsible for the structure of the Centre Pompidou in Paris, amongst other notable buildings, believed that the true innovators of the architecture of the Modern period were the engineers, arguing that it was the engineers rather than the architects who first developed the new building typologies – such as railway termini and the incomparable Crystal Palace – and that it was from these that the visual vocabulary of Modern architecture was derived. Happold believed that architects were simply manipulators of images and that this was largely a recycling process. Engineers, on the other hand, according to Happold, worked from first principles and devised new building forms that made appropriate uses of the ‘new’ materials of steel and reinforced concrete. The creation of new images was not their primary intention but it was nevertheless the outcome and it made available to architects a whole new set of visual symbols that would become crucial to the development of Modern architecture.

Fig. 2.1 Crystal Palace from the Northeast during the Great Exhibition of 1851; Dickinson, artist; Joseph Paxton, designer; William Cubitt, contractor; Fox, Henderson & Co., ironwork contractors. This building is celebrated by architectural Modernists as the finest example of a new building typology that would form the basis of a built environment for the developing age of science, commerce and industry. Its important features were the separation of structural and enclosing functions in its fabric, the lack of ornamentation and the reliance on the mass-manufactured products of industry, expressed by repetition of a basic module on a grand scale. Above all practical considerations was the image created by the crystalline purity of its transparency, that represented the spiritual and physical cleanliness and tidiness aspired to by the Modern world view. (Painting: from Dickinson’s Comprehensive Pictures of the Great Exhibition, 1852/Wikimedia Commons)

Happold’s views are, of course, controversial, although other commentators, most notably the prominent twentieth-century architectural and cultural critic Rayner Banham (1922–88), expressed similar sentiments.

Andrew Saint (1946–), in Architect and Engineer: A Study in Sibling Rivalry (2007), made the counter-argument that the innovations that followed from the introduction into architecture of ‘new’ structural materials, such as steel, were led principally by architects. This controversy is explored in this chapter where it will be seen that Happold’s and Saint’s points of view each have some validity, although they affected architecture in different ways. Happold’s ‘design from first principles’ did produce entirely new images – such as the glass-clad framework; Saint’s architect-led innovations led to the extension and development of existing typologies based on traditional approaches to architecture.

Ferrous Metals as the Hidden Enablers: Extending the Span Capabilities of Traditional Forms

As noted in Chapter 1, forms of hand-forged wrought iron and steel have been produced since prehistoric times. Their increasing availability since the time of the Italian Renaissance resulted in their widespread use in architecture, principally as tension-carrying elements in buildings constructed in masonry and timber.

Fig. 2.2 Hôtel de la Marine, Place de la Concorde, Paris, 1774; Jacques-Germain Soufflot, architect. The monumental scale of many of the buildings of eighteenth-century neoclassical architecture, such as this, was made possible by the use of wrought-iron tie bars in locations of high tensile internal force. (Photo: User:Moonik/Wikimedia Commons)

Fig. 2.3 Section of portico showing location of wrought-iron tie bars, The Panthéon (Church of Sainte Geneviève), Paris, 1790; Jacques-Germain Soufflot, architect. The reinterpretation of the Classical language of architecture in the neoclassical period, and in particular the larger scale of most of the buildings compared to those of Antiquity, led to the creation of high levels of tensile force in the masonry that were resisted by the insertion of wrought-iron reinforcing bars. (Drawing: from Addis, 2007)

A principal generator of tensile forces in Classical architecture is the straight span of the horizontal parts of the Classical orders, the beams and lintels of which are subjected to bending. This causes tensile stress which masonry has very limited capacity to resist. In Antiquity the problem was solved simply by restricting the span of beams, as in the peristyles of Greek temples, or by using timber, carved to look like stone, as the horizontal elements – as practised by many architects of the Italian Renaissance. The span capability of masonry was, however, often increased by the use of iron reinforcement, and this usage had become fairly common by the eighteenth century, very prominent examples being found in French Parisian architecture, including the church of Saint-Sulpice (1732), the buildings facing the Place de la Concorde (1774) (Fig. 2.2) and in the church of Sainte Geneviève (Panthéon) (1790) (Fig. 2.3).

By the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, iron bars were also being used to extend the possibilities of timber structures. The limiting factors with timber, which has more or less equal strength in tension and compression, and therefore in bending, are its relatively low strength (which requires the use of large sections if long spans are required) and the obvious restriction imposed by the maximum sizes of available trees. Built-up elements such as trusses require effective structural joints, which are difficult to construct in timber. Traditional carpentry joints involve cutting into the sections to produce mortices and dovetails, thus reducing carrying capacity, and the use of mechanical fasteners such as bolts and pins causes stress concentrations which can split the wood.

Fig. 2.4 Section of the Opéra at the Palais-Royal, Paris, 1770; Pierre-Louis Moreau-Desproux, architect. The large spans required for auditoria in buildings with thin walls that could not support masonry vaults were accomplished by the use of timber roof trusses. The scale of these could be increased by the inclusion of strong iron ties. Long tie bars are also used here to support the ceiling over the proscenium arch. (Drawing: from Saint, 2008/Photothèque de Musée de la Ville de Paris)

Despite these difficulties, iron components were used extensively in pre-Modern times to extend the span capability of timber structural elements. A prominent example was the use of iron tie bars in the roof trusses of the French Opéra at the Palais-Royal in Paris (1770) (Fig. 2.4). Christopher Wren, that most technically accomplished of English Baroque architects, used iron ties in the extensions that he designed to suspend a floor from massive roof trusses at Hampton Court Palace. This eliminated the need for some load-bearing walls on the ground floor and anticipated the utilization of the metal skeleton framework to make buildings with open plans.

Fig. 2.5 Théâtre Français, Paris, 1786; Victor Louis, architect. This is a very early example of a long-span roof truss made principally from wrought iron. (Drawing: from Steiner, 1984)

An obvious development from the use of iron elements to augment the strength of traditional timber structures was to produce a range of structural sections, in cast or wrought iron, that were suitable for making entire structures out of iron, and the initiative for this development was taken mainly by the ironmasters themselves. The stimulus for innovation was frequently the requirement for a long span and an early example was the trussed roof for the Théâtre Français in Paris (1786) (Fig. 2.5). Later examples in the early nineteenth century included the cast-iron girders over the King’s Library at the British Museum in London (1824) and the elaborate trussed roof for the House of Lords in the British Houses of Parliament in London (1845).

Cast-iron columns, which were considerably thinner than masonry or timber equivalents, were used increasingly from the eighteenth century in building types that required spacious interiors. Examples were at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, London (1791), in which the extensive balconies were propped on cast-iron columns, and several churches close to the centre of ironmaking in England such as St Chad’s Church, Shrewsbury (1792) and St George’s, Liverpool (1813).

Some of the best known examples in Western architecture of the use of iron to augment the structural properties of masonry were to be found in the design of large domes. The internal forces in domes are principally compressive, which masonry is well able to resist, but circumferential (hoop) tensile forces can develop in their lower parts. These produce radial cracking, which causes the dome to become a series of concentric arches which exert significant horizontal thrusts on supporting structures. The phenomenon had occurred at the Pantheon in Rome (second century CE), but in that case the very thick walls of the supporting cylindrical drum were capable of absorbing the outward thrusts. At the Hagia Sophia in Constantinople (sixth century CE) the outward thrusts were partially resisted by massive buttressing structures at the corners of the building but iron-bar tie rods, that crossed the space at the base of the dome, were also provided, and this may have been the earliest significant use of iron reinforcement in a major structure.

Fig. 2.6 Diagram showing cracks, St Peter’s Basilica, Rome, 1590; Michelangelo Buonarroti, architect. The masonry domes of the Renaissance period had to be self-contained structures and this required the use of circumferential iron chains. Failure of the original chains in the St Peter’s dome almost caused it to collapse. The dome was successfully repaired in the eighteenth century by the insertion of additional iron chains. (Drawing: Moore, C. H., 1905, The Character of Renaissance Architecture/Wikimedia Commons)

Subsequent large domes were supported on thin-walled cylindrical drums of masonry and this arrangement required that the dome itself become an autonomous structure that does not need lateral support at its base. To achieve this condition, rings of iron chains were embedded in the lower sections of domes to give them sufficient tensile strength to prevent radial cracking. All of the great domes of the Western tradition, including Brunelleschi’s cupola at Santa Maria del Fiori in Florence (1446–61), Michelangelo’s at St Peter’s in Rome (1546–90) (Fig. 2.6