Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Pushkin Press Classics

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

'Luminous... a vibrant portrait of African-American life at the nation's crossroads' New York Times Book Review 'A rousing, inspired work, keenly observed and soulful... the novel sparkles with life, soaring with the loose flow of a jazzy improvisation' Boston Globe Amerigo Jones grows up poor but surrounded by love in Jazz Age Kansas City. A precocious young dreamer, he longs for the college education that his parents could not have. But as Amerigo begins to venture further away from his doting mother and father, he encounters a world marred by prejudice, where amid the bustle and the beauty, violence and injustice stalk the streets. Such Sweet Thunder is a majestic and unforgettable child's-eye-view of Jim Crow America from a powerful chronicler of American family life. Amerigo Jones grows up poor but surrounded by love in Jazz Age Kansas City. A precocious young dreamer, he longs for the college education that his parents could not have. But as Amerigo begins to venture further away from his doting mother and father, he encounters a world marred by prejudice, where amid the bustle and the beauty, violence and injustice stalk the streets. Such Sweet Thunder is a majestic and unforgettable child's-eye-view of Jim Crow America from a powerful chronicler of American family life.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 1165

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

1

‘Luminous… a vibrant portrait of African-American life at the nation’s crossroads’

NEW YORK TIMES BOOK REVIEW

‘A rousing, inspired work, keenly observed and soulful… the novel sparkles with life, soaring with the loose flow of a jazzy improvisation’

BOSTON GLOBE

‘An extraordinarily honest and compassionate child’s-eye view of a world too seldom seen in American fiction’

KIRKUS REVIEWS

‘Echoes of Faulkner, Twain and Joyce… for its lyrical rendering of a time and place long vanished, this is a book to savor, slowly’

ENTERTAINMENT WEEKLY2

3

SUCH SWEET THUNDER

VINCENT O. CARTER

WITH A FOREWORD BY JESSE MCCARTHY

PUSHKIN PRESS CLASSICS4

SUCH SWEET THUNDER6

7

toduke ellington8

Contents

Foreword

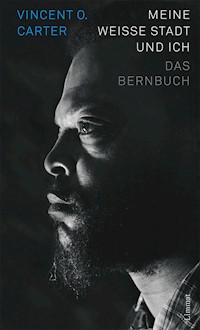

Great novels are not always recognized in their own time; often they lie waiting, as if in ambush, for the future to catch up to their achievements. In the case of Such Sweet Thunder, the miracle of its arrival at all inevitably continues to color its critical appreciation. We know something about the unusual circumstances that led Vincent O. Carter to effectively exile himself from his native Kansas City and take up residence in Bern, Switzerland (where he wrote the novel over the course of several years in the late 1950s and early 1960s), because of the only book that Carter would see published in his lifetime: The Bern Book.

This deeply ironic, essayistic blend of memoir, travelogue, and poetic meditation was successfully published in the United States in 1973 but, despite some favorable reviews, it was quickly filed-away and forgotten. Appearing at a time when black militancy and popular discourses about race were just reaching a fever pitch of declamatory and affirmative style, Carter’s arcane, cosmopolitan, and inwardly focused ruminations—qualities that would have made The Bern Book legible to what I have elsewhere called the “Blue Period” of black writing that lasted between 1945 and 1965—were, alas, a terrible fit for the reading public’s sense of what black writing should be in the mid-1970s.

The difficulties that this first book encountered had implications for the viability of the second. Despite the efforts of Herbert Lottman, who acted as Carter’s literary intercessor, and of Ellen Wright, the widow of Richard Wright, who read portions of the manuscript (at the time still bearing the working title The Primary Colors), no publisher would take it up and Carter eventually despaired of seeing it through to publication. He retreated from his attempts at writing and devoted himself increasingly to spiritual practice and to his shared life with his partner Liselotte Haas. He died in Bern in 1983.

The manuscript of Carter’s only novel, long believed to have been lost or destroyed, was thankfully preserved by the care of Liselotte Haas 10and retrieved for publication through the heroic efforts of Chip Fleischer, who recognized the importance of the manuscript and first published it under the magnificently braided Shakespearean and Ellingtonian title Such Sweet Thunder at his own Steerforth Press in 2003.

Despite its evidently eccentric stylistic flourishes and a somewhat contrived overture, Such Sweet Thunder is in many ways a fairly conventional Bildungsroman, or even more accurately a Künstlerroman that narrates the dawning of creative consciousness and of a sentimental sensibility in the boyhood and teenage years of Amerigo Jones, a character whose roving mind and synesthetic perceptions are clearly a stand-in for Carter’s vision of his own years growing up in the black working-class neighborhoods of Kansas City. These were the interwar years of the Depression, but also of the Negro League’s Kansas City Monarchs and their star pitcher Satchel Paige; the cradle of Kansas City jazz and its musical luminaries like Count Basie, Bennie Moten, and Charlie Parker; a time when black Kansas City was, tragically in retrospect, at a social and cultural zenith.

Such Sweet Thunder is centered in the mercurial consciousness of young Amerigo, yet his parents, Viola and Rutherford Jones, are every bit as much the protagonists—the beating heart of this novel—as he is. Based on Carter’s own mother and father, they are teenage parents and working poor: Viola works in a laundry and also as a maid (Carter’s mother Eola likely worked both of those jobs) and Rutherford (like Carter’s father Joe) works as a porter at a hotel. As with many of the details in the novel, the brick-and-mortar realism of the spatial and material cityscape is emphatically accurate, even as it chooses at times to withhold key details. The imposing Muehlebach Hotel is rendered with fidelity; but the humbler hotel where Rutherford works is never named, for instance. Yet because Amerigo places it at Ninth Street and Locust Avenue, we know that it must be the Densmore Hotel which indeed operated from that location from 1909 until it was demolished in the late 1990s. This feeling for the city is that of the exile, familiar to us from James Joyce whose obsessive reconstruction of Dublin in Ulysses is clearly one of the models for Carter’s depiction of Kansas City. Indeed, Such Sweet Thunder is inspired by Joyce not only in this sense, but perhaps even more so with its plentiful stream-of-consciousness riffs and colorful 11uses of onomatopoetic language that echo Joyce’s A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, with, in Carter’s case, the addition of a magnificent ear for the cadence of small talk among black folks.

During one of his only return visits to the United States, Carter saw for himself the staggering devastation of what had once been a world of throbbing multicultural and interethnic vitality, rife with racial tension and violence to be sure (an aspect Carter vividly captures in all its quotidian banality), but nonetheless, a community brimming with what Carter conceived of as a web of aesthetic relations: between jazz on the radio and the gestures of aunties cracking wise, the vocal timbre of men hailing each other in the street and the rumble of streetcars at Eighteenth and Vine, between the poolhall slouch and the preacher’s lean in the pulpit; the dense matrix of communal black life in an urban setting marked by the dominant presence of poor, working people with immense belief in their own talents and abilities and ever scornful of the racist forces regularly lashing out at them and reminding them of their place. In a letter to Lottman from 1973, Carter lamented this lost world that, paradoxically, flourished under segregation:

It had all changed, Herb, it was all different now; the people were gone and the houses were gone; in their place was a super highway. Only the light was the same: sunlight at seven in the morning, at noon, at five o’clock in the evening when dad used to come home from his hotel. Perhaps it was when I boarded the plane for New York that I realized that nothing has been lost. I had written it all down—that fabulous world of childhood, the world of mom and dad young, laughing and in tears. It was all in The Primary Colors, my way, and what I couldn’t say because one can never say it all, is written in my heart.

But Carter’s vision cannot be reduced to the idiosyncratic story of one young man’s personal emancipation against a screen of nostalgic reminiscence. The work of ideological mythmaking has ensured that what happened to downtown Kansas City remains in large part a mystery to most Americans (including black Americans), who cannot seem to imagine 12that it was ever anything other than the cross-roads of highways, banks, convention centers, and empty lots that now defines it as predictably as virtually any other important urban center in the country. What Carter wants us to see—to make us feel grievously as an immediate loss—is a tragedy that holds a much broader allegorical force within the national narrative of the United States, and with particularly fierce poignancy in the historical memory of African Americans. It stands for the unpardonable ruination of the first black working class, the massive squandering of the heroic efforts undertaken by the first generation of black freedmen and women, the formerly enslaved and the sons and daughters of the formerly enslaved who took off their shackles only to get to work building up the first free black neighborhoods across America’s cities, everywhere under duress and festering resentment, and often under the hooded overwatch of the Klan’s terrorism and the de jure apartheid of Jim Crow.

One can think of other classics of African American literature that know these people and tell aspects of their story: William Attaway’s Blood on the Forge; Ernest J. Gaines’s A Lesson Before Dying; Margaret Walker’s Jubilee; Richard Wright’s Uncle Tom’s Children; and Lorraine Hansberry’s A Raisin in the Sun, to name a few. Yet, none arguably captures quite so aptly the note of gallant hopefulness, the tender vivacity, the sarcasm and cunning that generation seems to have possessed in such abundance as the novel you hold in your hands.

Anyone who ever knew black folk of that era, knows something of the distinctive grain of the voice that they brought into the world. Everywhere the grain of that black voice was allowed to show up it changed the world; in popular music, in sports, in the arts, in politics, in fashion, in everyday speech, and yes, in literature.

In her striking work of literary criticism Liberating Voices, Gayl Jones makes the argument that the African American novel emerged out of the struggle of black writers to incorporate their own “distinctive aural and oral forms” into the representational conventions established by the European realist novel. The opening pages of Such Sweet Thunder do seem to groan as Carter struggles to stage Amerigo’s encounter with the Proustian madeleine that will open the floodgates of memory to his lost Kansas City. It’s no coincidence that the vehicle he lands upon, 13however, is a copy of a newspaper called The Voice, an obvious allusion to the legendary Kansas City Call (still extant), one of the oldest and longest-running black newspapers in the United States. The black press and its once improbable reach and influence are now something of a spectral myth, acquiring that vaguely legendary sepia tint that also attaches to the Negro Leagues and other bygone relics of an era that our popular culture has seemingly no capacity or desire to meaningfully remember. Yet the idea to use the black newspaper both allegorically as a symbol of a historic community, and formally as a choric voice, is perhaps the masterstroke of genius in Carter’s novel. Without the opening vignettes, we would lose sight of this deliberate construction.

As a scholar I can appreciate Such Sweet Thunder as a miraculous recovery and a remarkable example of what was possible in black post-war fiction. But as a novelist, I appreciate even more how it does things in prose with such a wondrously open sense of freedom. It is unsparing when necessary, yet humming with grace and good humor. It is also a social novel, passionately carrying us through living rooms and street corners and social dances in virtuosic passages that linger long after we have left them. It remembers for us a world that deserved its own bard and, recognized or not, has always had one.

The novel’s gift to us is ultimately the achievement of this tremendous sense of voice, or rather the orchestration of its collective voices, newspaper-like you might say, but swinging like a jazz ensemble. This is a book I have wanted to read late into the night. It stays with me in those quiet hours, even after I put it down, its rolling thunder unfurling just above my head.

jesse mccarthy

Rome, June 2024

Such Sweet Thunder

On a cold winter morning shortly before dawn in the year 1944, the stars shone brightly, but were now and again obscured by drifts of heavy clouds.

The Great War, which was then ravaging the earth, seemed to be asleep. Nevertheless, the soldiers slept restlessly within the confines of a large racetrack on the outer limits of the northern French city of R——. The camp occupied more than two-thirds of the entire track—long rows of barracks connected by gravel lanes that extended from the periphery to a large inner field that served as a parade ground.

Now all was obscured by darkness. The hollow chamber of the huge cementlike structure that loomed over the barracks from the far end of the field had once been the reviewing stand, but was now merely a bulky mass filling in the final segment of the track. Its wooden benches and flooring had been hacked into firewood by the freezing civilian population. This shell seemed to echo the cries of death choking the throats of the French, English, and American soldiers who had slept nervously in the same encampment during the First World War of 1914.

Now the soldiers within the barracks tossed and turned while the sentries who stood watch from the nine posts along the outskirts of the camp looked warily out into the dark.

A bell rang from a tower in the town, and a beam of light flickered in the darkness. A hoarse command separated itself from the voices echoing in the shell:

“All right, then! You-had-a-good-home-but-you-left-it!”

The sergeant of the guard roused the sleepy men from their bunks and they stumbled out of the guardhouse, moving sluggishly, in loose 16formation, their rifles slung carelessly over their shoulders, their heavy boots grating against the frozen gravel.

After plodding along the track for a short distance, they broke through the open field that, covered with frost, made them look from a distance like specters tramping noiselessly through a bank of clouds.

Half asleep, shivering with cold, they straggled along, halting at first one post and then another, grunting unintelligible signs of recognition to the companions they were relieving who, impatient for the warmth of their beds, hastened back to the guardhouse.

Finally the last guard made his way toward his post. It was five or ten yards from the reviewing stand, and somewhat isolated from the rest of the camp. This hintermost area was surrounded by a dense forest, beyond which lay the southern limits of the city.

“It’s Jones, Roy!” cried the approaching soldier in a youthful sonorous voice. Roy, within the hut, hastily threw the lid on the old oil can in which he had made a fire and stepped outside. “It’s cold as hell!” Jones added in as manly a tone as possible.

“You think it’s cold, man?” he answered.

Confused, Amerigo Jones shivered past him. “Say, man—”

“Yeah?”

“—you can have ’er, if you want ’er.”

“What?”

“What?”

But Earle had disappeared in the dark.

A hint of rose coloring burned imperceptibly brighter in the blue-black sky. A bit disconcerted, Amerigo entered the hut and immediately tried to restart the fire thinking, as he poked into the can with the butt of his rifle, that Earle must have said something quite different from what he thought he had said. Nevertheless, the words “You can have ’er, if you want ’er” stood out in bold relief in his mind, the word her mysteriously separating itself from the context of the sentence, filling him with a titillating excitement.

Now what did that mean? he pondered, standing his rifle against the wall beside the can. The great Roy Earle! He fumbled in his pockets for 17a match, and as he fumbled he saw Roy dressed in neat-fitting purple trunks—taller, more robust, and generally more handsome than he—prancing arrogantly in the ring of the high school gym, animated by the enthusiasm of the crowd. He tried to pacify himself with the reflection that Roy’s eyes were small and puffed and that his nose was crooked from having been broken. But then he heard the voice of his mother telling him that he would have to develop the beauty within because he would never be a movie star. The thought of home, of high school, flashed through his mind, and gradually he became immersed in the warm feeling of spring.

Of a particular spring, he felt, the imperative emphasis rising to the surface of his excitement. A feeling of intense pleasure rippled over his consciousness, and he strained his memory in an attempt to discover its cause, vaguely remembering that it had somehow been provoked by his willful abstraction of the word her from the rest of Roy’s words.

Nor did it strike him as peculiar that a burst of autumn colors now imposed themselves upon his awareness of spring, for his thoughts were stumbling on so swiftly that the unknown face hiding within the shadow of the word her was swept up into a flurry of words that now flooded his mind and filled him with a sweet melancholy sadness.

The rosy glow died out of the fire. Her.

The fire’s gone out he thought, embarrassed because he could see no connection between the word and the fire. He wondered why he thought there was. His eyes came to rest upon the little square window in the door of the hut. A faint, very faint, blue light crept in through the dirty window. It was spattered with dried drops of rain, and wedges of frost had entrenched themselves in the corners.

He struck a match. The yellow flame made his shadow dance upon the wall and break into three grotesque planes where the ceiling joined the wall and caused the rusty can of dead embers to dance and bend and merge into his shadow. The floor was spotted and stained with filth. A dried-up rubber lay crumpled among the warm ashes that spilled out of the little draft hole near the bottom of the can. While impulsively burying it with the toe of his boot, he spied a piece of soiled paper just behind the can. He stooped to pick it up. The match went out. He lit 18another, and bent over to inspect it more carefully, but the flame flickered out before he could decipher the name of the paper under the coating of dirt. He lit another match.

The Voice! Damnit! He rubbed his hand to cool the stinging pain in the tip of his thumb. Anxiously now he lit another match and saw that he held a part of the society page in his hand. His eyes fell upon the face of a young woman in the center of the sheet, stained by a muddy boot print and torn in such a way that little more than eyes, nose, and a corner of her mouth, which seemed to be smiling, were visible.

It’s her! he whispered excitedly. And the spurt of air on which the word her issued from his lungs blew out the light. Nervously he struck another match, but was so excited that it was only with the greatest difficulty that he was able to read.

But wait! Just as he began to read, the sound of the wind filled his ears. It whipped through the frozen trees in the surrounding forest and dashed unseen branches to the ground. It echoed in the hollow shell towering above the hut and mingled with the whispering colors of the dawn. So striking was the effect that Amerigo half believed that a host of devils insinuated themselves into the words, as he read:

“Miss Cosima Thornton, only daughter of Mr. and Mrs. Elijah Thornton, of this city, was wed to Mr.…”

A serried line obscured the identity of the anonymous man and converted the square that had contained the photograph into a triangle. The match went out. Seconds later he felt the cold creeping through the square blue window. He shivered, as if he could recover from the shock of seeing the smudged mutilated face of Cosima lunge out from the shadow of the word her.

It’s an omen! he thought. But then—that’s crazy! But still. It must mean something! She … we …

The cold crept up his spine.

I must make a fire. Guiltily he considered the society page of the Voice. Actually, it’s only a piece of paper, he argued. And suddenly a conscienceless hand had tossed it amid the warm ashes, while the other withdrew a knife from his pocket and whittled a few shavings from one of the two-by-fours in the wall of the hut. He felt a pang of remorse as 19he lit the paper and watched the shavings ignite and the dormant fire sustain the flame.

Forgive me, Cosima! he exclaimed. Outside the hut the icy branches creaked in the wind.

It’s strange after all this time. I didn’t recognize her at first. Now there she is, burning in that damned can. It’s not Roy’s fault. Whose then? Perhaps if there hadn’t been a war? If!

He shaved more wood from the post, and the fire grew brighter.

She’ll be sitting by the fire, he mused. Breakfast on a cold winter morning such as this, with Mr. What’s-his-name, over orange juice and toast! She’ll unfold the crisp clean pages of the Voice and read beneath the photograph of a grave young black man with eyes that peer into the very depths of her soul:

“Amerigo Jones, only son of Mr. and Mrs. Rutherford Jones, of this city, who was killed in the heroic act of.…”

While he pondered the heroic act he heard her heart pounding within the aching void of profound regret. Stirred by a deep feeling of pity for her, rewarded for all the suffering she had caused him, he extended his small black hand in an attitude of forgiveness, through the cold blue sky and across the stormy reaches of the Great Atlantic Ocean! She shed a penitent tear upon it and caressed it piously. Thus consecrated with love, his martyred body exploded into dazzling filaments of purest light.

“I will love you always!” he whispered.

From outside the hut came the sharp crack of a broken twig. He stood breathlessly still. Something stirred in the brush, hesitated, and moved again. He carefully took up his rifle, quietly shoved the bolt home, and kicked the door open.

A woman stood there.

More rose coloring had filtered into the sky, intensifying the yellow of her hair. The firelight caught her pale oval face, but the lower part of her body was in darkness.

Without a word she stepped past the muzzle of his rifle, past the astonished look upon his face, and stood shivering in the far corner of the hut.

Just a girl! Not more than sixteen.

20Confounded and somewhat embarrassed by the intensity of her gaze, he leaned his rifle against the wall. Her hair looked as though it had not been combed in a long time, and her eyes were an intense shade of blue.

She stood calmly—no longer shivering now that the fire had gradually thawed the coldness in her body—and allowed his frankly bewildered eyes to ferret out the deep violet lines that circled her own. A patch of golden down fringed her thin upper lip; the bottom lip was slightly drawn, more from a sort of animal toughness than from fear of him. She’s surely not ashamed, or proud. Just here: Post No. 9, 1944, twentieth century. Her ridiculous G.I. coat almost reached her ankles and was missing all its buttons but one, which was securely fastened. What he could see of her legs terminated in a pair of combat boots.

His whole consciousness became absorbed in a vital awareness of her eyes, which seemed to have swallowed all the perceptible worlds between them.

The wind rose with an anguished moan.

He glanced guiltily at the fire. It’s only a dirty scrap of paper! he argued. But now it’s a part of the flame.

He looked into the girl’s face, as though to deny the fact that the flame cast a mellow glow upon it.

You can have ’er, if you want ’er.

He impulsively stabbed at the hot embers with the blade of his knife. Then without knowing what he did, he withdrew a package of rations from his pocket and gave her a part of its contents. She took it and ate in silence.

She’s done this many times, he thought as he poured some coffee into his cup and handed it to her, drinking himself from the canteen. When he had finished he slung his rifle over his shoulder and went out to fetch wood for the fire, thinking: Maybe she’ll go away. But when he returned minutes later with a few frozen branches she stood in the corner, as before. He threw some wood on the fire and then squatted before her.

“Now,” she said.

He could see her body through her thin rag of a dress that was either blue or green and fastened at the neck with a pin. Her underwear, which might have been a soldier’s olive-drab shorts, could be glimpsed 21through a bursting seam. A pair of army socks crumpled around the tops of her boots.

“I will love you always!” he heard himself saying, and a cold fear seized him. The wind rose and in its wake a procession of grotesque figures seemed to dance obscenely in the light of her pure gaze. He reeled in the upsurge of dimly perceived events flowing within his visual range with varying degrees of clarity, flaunting every previous notion of himself.

It shouldn’t have been like this! he thought in despair.

He tried to remember Cosima’s face. But now he was tempted to look at the woman again, as though he half expected her to be Cosima. Cautiously, he raised his eyes as far as her boots. Then, with a sweeping glance, he took in her body, her face, and then he looked into her eyes.

“Now?”

Wait a minute! he cried desperately to himself, for it now appeared to him that the woman’s features were actually changing before his eyes. He stirred the coals in the can. The flame grew brighter.

“Cosima?”

A branch fell to the ground with a loud crash. His mouth flew open as the woman’s eyes changed from blue to brown, her hair from blond to soft brown.

Is it possible? … Yielding to the dazzling sensation splashed in hot spring colors. What if I can’t stop this?

The woman’s skin grew darker. Her nose broadened at the base and her cheekbones swelled gently under her eyes, which grew larger, the lashes longer, giving them an intense dreamy expression. Her lips became fuller in a face that was radically different from that of the girl who had lain there before.

It’s no use he mused sadly, but not without a subversive feeling of pleasure, as he relaxed and allowed his mind to be subdued by his fancy. It can’t all be just imagination. But … but how could this be Cosima. His eyes struggled to avoid the flesh under the flimsy bodice of her dress.

And now he perceived that her body had even diminished in size! There can be no doubt! he thought, passionately abandoning himself to the sight and thought of her. Her lithe body now flitted upon the horizon of his fondest recollections.

22The spring of ’41. The gym … North High. The setting sun was streaming through the three great windows.

Music at four. Chester Higgens on drums and Daisy Logan on piano. Faces crowded around the bandstand, listening to Tommy Wright on trumpet from Jay McShann’s band in town.

Dancing with Cosima! Looking guardedly over her shoulder at the side of her face, at the soft wisp of hair caught in the sunlight: on the turn, at the edge of the crowd.

To the blues. Shuffling back and forth on ball and toe of nervous feet. Once, while getting ready for the turn his arm tightening around her waist, heel turning on the pivoting point, her body pressed against his, faces forced apart, yet drawn by the magnetism of inexpressible joy!

Caught, in the swing of the turn, his thigh locked between hers, heel spinning like the axis of the world, her wide skirt billowing like a sail!

Stunned! Dazed! In the middle of the floor amid the fury of applause, stamping feet and yells of enthusiasm:

Cosima?

Lost? Lost! In the wake of the furling yellow skirt, fleeing through the sea of sunlit sound! …

A bell rang from a tower in the town. Voices in the shell rose to a voluminous whisper:

Cosima’s not there! Cosima’s not there! Cosima’s not there.…

A dull pain throbbed in his head.

Cosima!

Cosima’s not there!

“It’s only a thought!” he cried angrily. “It comes from me!” He studied the woman’s face.

She’s smiling. Why does she smile? How small her mouth is! And then he thought knowingly: She always did look like that when she was … Her nose is—is like mine! He closed his eyes and saw the ripple of animation that broke over her smooth black face whenever she spoke.

Mom?

23He opened his eyes and beheld the woman with his face lying on the floor. She had balanced herself upon her elbow and had drawn her left leg toward her chest. He looked beseechingly into her eyes.

And now he felt the warmth of her flesh tenderly enveloping his naked body. His tiny fists clutched at her breasts. He closed his eyes and sucked with a hungry passion.

Boom! A deep bass voice boomed in his ears:

“Such a big boy like you, suckin’ his momma’s tiddy!”

He looked up and saw the woman’s breast protruding between his eyes and the hairy face of a man. A killing shame smote him.

“It’s not my fault!” cried Amerigo, enraged by the sight of himself, floundering in a state of infantine helplessness. At the same time his feeling of shame was intensified by an irresistible desire to embrace the woman, to seek refuge between her parted legs. The desire grew into a great longing, like that of an intensely felt homesickness. Meanwhile his body grew smaller and smaller in an attempt to hide from the dangerous face.

“It is not possible!” he cried, noticing that his voice made a small, round, barely audible sound. “No!” But his body continued to grow smaller. He entered the woman’s body. He allowed his thoughts to sink down into the alluvial blackness, to the rhythms of myriad beating hearts. So loud that he was reduced to a mere amorphous awareness of himself, flowing through ancient worlds of flesh and bone strewn between the canyons of buried mountains and dry seas; a whirling rainbow brightness caught in the vortex of an irresistible force.

A bell chimed from a long way off.

He discovered himself staring fixedly into the woman’s eyes. He saw the night. A boy and girl appeared. They climbed secretly to the crest of a great hill covered with wild blue grass and disappeared behind a clump of bushes that shot giant sprays into the air.

Rain and the feet of many generations had worn deep hollows into the breast of the hill, so that here and there—now hidden by a soft knoll, a bush, a knot of tangled undergrowth—lay the secret place where the thing was done: Boom! The seed plummeted deep into the root-breeding depths of the still cool darkness. The first of the ninth month, in the year ’23, on a starry night in June when the scent of maple and pine, 24wild rose, and lilac filled the air.… He saw the day: Boom!—and the slow rhythmic pain resounded in the girl’s abdomen.…

The boy’s handsome face filled the woman’s eyes. He ground his teeth and bit into the flesh of his bottom lip until it bled. Dad? His eyes fixed upon his father’s face, Amerigo felt himself drawing nearer to the brink of time, within audible range of the inevitable question. Rutherford wrung his hands and muttered to himself:

“I didn’ know nothin’ like this was gonna happen! What am I gonna do with a baby? Just a trap! Her word against mine!”

“Tee! hee! hee!” A strange woman’s voice, but no face appeared.

“Black thing!” Another woman’s voice. It was familiar, but he couldn’t place it.

“A tramp!” A man.

“… You—a father!” The voice of an older woman, which he felt he had heard many times. “Why, boy, you just a baby yourself! Besides, how do you know it’s yourn?”

Boom!

A shriek escaped Viola’s lips, followed by a lusty cry. Rutherford studied the features of the small black baby in Viola’s arms, which now appeared in the woman’s eyes. Its eyes shut tight, fat hands doubled into fists, it kicked as though it were falling through space. Amerigo thought it resembled himself.

“Don’ look nothin’ like me!” said Rutherford reproachfully.

“He’s too little to tell yet,” said Viola. Her eyes were clear and bright with remembered pain, her lips dry and parched. “Somethin’s finished in me …” she whispered, “… over. Ain’ nothin’ gonna change that. Not just bein’ up there on that hill with my spine pressed against that knoll. That was somethin’, all right. But this is somethin’ else! This I had to earn! Had to suffer, all by myself!” She looked up into Rutherford’s face and read the fear and doubt that were there. Then she turned to Amerigo and whispered bitterly: “Adam’ll have as many brothers as the ocean’s got teeth!”

“But they always leave you in the end!” The hoarse tubercular voice of a woman who was no longer young, but not old. “They only want you 25to ween ’um. Once they git on they feet, git the craze to see a diamond cut a heart, they gone. The devils!”

The woman’s face appeared. She spoke as though she were ill or drunk, cursing a man with words of endearment. “Your poppa! Your poppa had eyes that could light up like hell! ’Specially when they’d git to shufflin’ with them dice an’ cards roun’ the gam’lin’ table. Mercy! Rex … Rex! That was my sweet devil’s name. An’ he was dangerous, too! Like sin. Played any-game-a-chance that was ever played. An’ when them run out, he’s up an’ make up his own! Why, he’d bet on the length of the knife that was stabbin’ ’im to death if the one who was stabbin’ ’im would stop stabbin’ long enough to call it!

“Fordy-two when I first met ’im. Darlin’ Sarah, my pa—Jethro was his name—usta call me. I was just turnin’ seventeen that spring. That was the year I got married to the gam’lin’ table.

“Between games I had babies. First Oriece. The Lord took him away from me when he wasn’ but one an’ a half. But He made it all up by givin’ me Ruben! An’ then Viola, the baby.

“When she wasn’ no more than ten it was a long hard winter. They daddy’s luck was just as hard as the winter was cold. One day he hadn’ been home for three days. An’ pretty soon them three days was over three weeks! After that I never saw ’im no more.…”

“Your gran’ma,” said a new voice, a woman’s. “Your gran’ma cried her eyes out, but it didn’ do no good worryin’ ’bout how she was gonna git through the night or if Rex’s game was good or bad, if he was gonna be mad—or glad—when he finally did come home.”

“One glad night was worth a thousand mad ones!” Grandma Sarah exclaimed.

“Yeah, darlin’, but one day he came no more.”

“No more …” Grandma Sarah whispered. “Come ’ere, the devil said. I hear it an’ hear it always like he said it the first time.”

“That’s just whiskey talkin’, Sarah. If you ain’ careful it’s gonna talk you to death. An’ if that don’ do it, honey, T. B. will! Did,” the woman added sadly. “An’ after that Ruben supported the family. Vi was eleven. He had his momma’s face—little an’ roun’—with a little sharp chin. Had a way of cockin’ his head on the side when he was in earnest, just like her.”

26A young man’s face appeared that looked a lot like his mother’s face and a lot like his face.

“Of course,” the woman continued, “his hair was crimpy, too, but not as good as Sarah’s. Nappy! she usta say when she wanted to tease ’im. He’d smile an’ then look just like his daddy. An’ then Sarah’d be through for the night!”

“Viola was j-e-a-l-o-u-s!” cried Rutherford.

“Yeah, I admit it!” Viola exclaimed, “but I never held it against him! I loved him, too! It wasn’t my fault that my father died when I was too little.”

“Died?”

“Went away.”

A low animated murmur rose from the shell, as several unidentified voices began to speak at once:

“That Ruben had a million-dollar smile!”

“Cute, too!”

“An’ dance!”

“The only trouble with that good-lookin’ black boy is he was born too early!”

“Your Uncle Ruben was a dancer, boy!” he heard his mother saying above the other voices, and he wondered how many times he had heard her say that, especially when he couldn’t do that break-step she was always trying to teach him!

“My daddy,” she would say, “had hands like a devil, Momma always said. My brother had feet like a angel, an’ you—you got feet like knees!”

Her face broke up with laughter, while Uncle Ruben illustrated the break-step again. Then he tried it with his mother, and she exclaimed, “No—no, that ain’ it!”

“Even your daddy could forget,” said the woman’s voice that had been speaking to Grandma Sarah, “that you look more like your momma than you do him to praise Ruben’s dancin’!”

“M-a-n, he sure was somethin’!” Rutherford exclaimed. “An’ I don’ mean just tata ta-ta-ta! I mean that joker could really git up an’ go! I remember that night, Jack, that night at the Black an’ Tan? Never forget it as l-o-n-g 27as I live. Where the Black Angel usta be, ’cross from the Italian bakery on the corner of Independence an’ Charlotte.

“Ruben was workin’ at the hotel an’-an’ had to work late that Saturday. He fell in about twelve. I mean the joint was jumpin’! Them jokers was strugglin’. Layin’ ’um, Jack. Drinkin’ sneaky-petes from flasks that you had to hide in your pocket, or stash under the table. Them jokers was payin’ three an’ a quarter a half-a-half-a pint, an’ six bits for the ice!

“Bus Morton was playin’, an’ man! I mean he was really hittin’ ’um! Them jokers was rough! Bus was on piana, an’—what was that li’l short joker’s name that played the cornet, Babe?” turning to Viola.

“Knuckles.”

“Yeah, that’s right. They called that cat Knuckles, Amerigo, ’cause his hands was so b-i-g! How he could play that cornet with hands like that, I’ll never know. But that joker could blow! An’ all them jokers was rough. An’ lookin’ nice, Amerigo, in fine togs, with they moss all layin’. Them cats had c-l-a-s-s, Jackson!

“Your momma had on the toughest dress she e-v-e-r had. Silver, with a long low neck. Fell straight from the shoulder an’ hit just at the knees, with fine fringes hangin’ down. An’ those rhinestone shoes she keeps in the closet. Boy, when that black woman brought that dress home I coulda killed ’er! She’s a-l-l-ways been like that, though, even when she was a li’l girl. Always had to have the best! It took us both six months, workin’ day an’ night—I ain’ kiddin’, am I, Babe?—to pay for it.

“But she sure looked nice! Didn’ nobody look no better. Your momma was a dresser!”

Rutherford’s voice grew thoughtful.

“I was standin’ pat in ma gray bo-back, Jack!” Grinning with pleasure: “It was really hittin’ me! I don’ remember what I paid for that suit. Wait a minute! Sexton bought it for me. Yeah. He a-l-l-ways had a big roll a bills. Big enough to choke a hoss! It was my first tailor-made suit. Formfittin’, Jack! With white Florsheim shoes and a dark blue tie. Silk! With a hard knot layin’ right in the heart a that collar. Tab. An’ then, on top a that, I had Sexton’s diamond stickpin, layin’ right up under that knot. So bright it’d blind the sun!”

28He paused, as he always did, to fully enjoy its brilliance.

“Me an’ your momma was layin’ down a Camel Walk while you was home ’sleep!”

“You always went to sleep right away,” said Viola, “an’ slept the whole night through!”

“Ruben fell in about twelve,” said Rutherford. “Lookin’ like one of those big-time cats out of Chicago or New York or somethin’ with a winnin’ smile that killed ’um all! What you say! Some niggah yelled, an’ a-l-l the people started lookin’. ‘It’s Ruben!’ they all said. Didn’ they, Babe?”

Viola grinned proudly.

“He couldn’ hardly git over to our table, for smilin’ an’ shakin’ hands! Like he was the president or somethin’! Rachel was a-hangin’ on his arm, puttin’ on airs, like a fool!”

“Rachel!” exclaimed Viola with contempt.

“But she looked nice, though!”

“Aw!” retorted Viola.

“Rachel was no good, Amerigo,” said Rutherford, “she was a bad woman. Lazy an’ triflin’. Spent Ruben’s money faster’n he could make it. An’ d-r-i-n-k! Drink more than a man. An’ she was eeeeevul! Nobody liked ’er.”

Uncle Ruben did, thought Amerigo.

“But she was a pretty woman, Amerigo, one of the prettiest women—black or white—I ever seen! Ain’ that right, Babe?”

“Rachel!” Viola spat out the word in the same tone in which she might have said whore.

That’s what she really means, Amerigo thought. But she can’t say it because of me.

“Anyway,” Rutherford continued, “he held the chair for her an’ ever’thin’. Ruben was a gen’leman! An’ before he could set down the jokers started yellin’ Dance! Dance, Ruben! Do a Buck-an’-Wing! Break ’um down with a soft-shoe! Eagle-Rock, baby!

“An’ then that joker on the drums started a soft roll on the snares. It got louder an’ cracked up all golden-like when that cat hit the cymbals! An’ then he rattled off a finger roll. Light as a feather! All the cats got quiet, waitin’ to see what Ruben was gonna do.

29“Then Ruben, your uncle—it’s a pity you never knowed him, he sure liked you, didn’ he, Babe? Well, your uncle Ruben stepped up on the stage in front of a-l-l them jokers! Modest, Jack! That’s what I always liked about Ruben. Cool! Like-a-a-aristocrat! An’ he didn’ let it swell his head the way Rachel did. Well, he stepped up on the stage. An’ the Baby Love—the baddest drummer that ever was!—started to hittin’ at Ruben on the cymbals!

“Ruben glided into a soft-shoe, with a easy rhythm that was g-r-a-c-e-f-u-l! Man! Wasn’ it, Babe?” looking at Viola for confirmation. “Like he was dancin’ on air!

“An’ then Baby Love let loose on the snares, watchin’ Ruben’s feet, the bass ridin’ easy: a-boom-boom-boom-boom.

“Ruben answered the niggah, an’ went ’im one better. An’ then he changed the beat on ’im before he could get set. But Baby Love was on ’im, Jack! Like white on rice! That Baby Love was m-e-a-n! You heah me? The joint was so quiet you could hear a rat piss on cotton.”

“Rutherford Jones!” cried Viola.

“An’ then what happened, Dad?”

“Then!” exclaimed Rutherford, looking at him in surprise, as though he pitied him for not having been there. “Then? Boy, Ruben closed his eyes. Like this.” Rutherford closed his eyes like Uncle Ruben, and the long silk lashes fringing the lids lay upon his dark, reddish brown skin.

The best-looking man in the whole world, Amerigo thought.

“Like this,” he was saying, “an’ then he let his arms fall to ’is sides. Relaxed, Jack! An’ then he danced. Danced! For a solid hour! An’ he never did the same step twice!

“Baby Love put his drumsticks down an’ just watched Ruben! An’ the rest of the jokers in the band laid their instrument ’cross their knees. Every foot was tappin’ while old Ruben was dancin’. Yes, sir, like God was callin’ the steps! An’ all you could heah was: Whoom! Whoom! Whoom! To-to-to Whoom! Whoom! Whoom! An’ in between the ‘Whoom! ’ Ruben was dancin’ every step that ever was. An’ when them run out, he started makin’ up his own!”

Like Bill Bojangles Robinson, Amerigo thought. Must a been something like that.

30“Then Rachel started playin’ the fool,” said Viola sadly.

“Yeah,” said Rutherford in a tremulous voice, “she started messin’ ’round with some niggah from the south side. A one-eyed niggah. She encouraged ’im ’cause he had a wad of bills. He started feelin’ all over her, an’ when she tried to get away from the niggah it was too late.

“Ruben looked up just in time to see ’im kissin’ her. The joint got quiet, and the people started movin’ back. Ruben leaped at the niggah—from the stage! G-r-a-c-e-f-u-l!

“Some woman yelled out ‘Look out, Ruben, the niggah’s got a knife!’ But he didn’ have no knife, he had a gun! A twenty-two automatic. Shot Ruben in the chest—two feet away. Then he made a dash for the door, flashin’ his gun. Little John emptied his forty-five at him, but he was gone.

“The hole in Ruben’s chest was too small. It closed up and he couldn’ bleed. By the time old Doc Bradbury got there Ruben was dead. “They never did catch the niggah that done it.”

“They never tried!” Viola protested bitterly.

“Why should they? Just one niggah killin’ another niggah.”

In the thoughtful silence that followed Amerigo was smitten by a profound regret that his cousin Rachel’s green eyes and soft golden skin had made a hole in Uncle Ruben’s chest that was too small, and that “they,” who were supposed to deal with such people, didn’t care at all.

“He was born too early,” said Rutherford. “If that dancin’ black man had been white!” He paused abruptly, speechless before the enormity of his speculation. “Yeah … an’ your momma was a good dancer, too, Amerigo. Won every Charleston contest in town. An’ she could do a mean Black-bottom, an’ a Eagle-Rock that was better’n most, an’ she could Buck an’ tap an’ toe.…”

“All I know is what Ruben taught me,” said Viola. “I usta like to dance with your daddy ’cause he could do the Camel Walk so well, with those long legs of his! An’ when he got a little tight he could do a real mean Shimmy, too!”

As his mother’s voice faded away, his father’s expression became grave. Amerigo felt vaguely uneasy, but he was not surprised or mystified by 31it because he gradually remembered the source of the feeling and was finally able to isolate it. He strained to catch the whisperings of the wind.

Rutherford, his five sisters, and a brother lived down on Fourth Street behind the old Field House opposite Garrison Square where the old Garrison School used to be. Opposite the schoolhouse stood Clairmount Hill.

It stood proud as a mountain, looking down upon the grand Missouri River and the huge dingy factories strewn along its banks. And upon the railroad machine shops with their sprawling yards stained with burned oil and soot, cluttered with odd wheels and dismantled engines and piles of worn-out brake shoes and all manner of wire bales, and bells and drums and bolts and rings and elbows and joints of iron and steel eaten up with rust; shops guarded by rough-hewn men in black leather jackets, closed in by strong rusty iron fences that had stood long in the rain.

Clairmount Hill was a stormy hill in spring when lightning lashed the trunks of the tall trees, raising welts of fire as the wind buffeted their splendid boughs.

The hill caught in storm raged in the reclining woman’s eyes.

Then a familiar voice rose above the wind: They ain’ no better’n you! It sounded like his mother’s voice, and then again like his grandmother’s, Darlin’ Sarah. He thought he knew the voice, and was agitated because the face did not appear.

“Rutherford,” it continued, “grew up in that old shack down at the foot of Clairmount Hill. Every time it rained the mud washed down its sides an’ flooded the street. Ran right up to the foot of the house like a volcano blowin’ up with mud! The one on the corner where the street ended, a frame house with three rooms. His momma, Veronica, his sisters: Ruby, Jessy, Nadine, Edna, an’ Helen—an’ him—all crowded together like Cracker Jacks in a Cracker Jack box. A course, the high an’ mighty Sexton didn’ live with the rest of ’um, he lived up on the avenue. The oldest—if he’d a lived long enough.”

“A man like him don’ come out of every belly!” Another familiar voice, a woman’s. It resembled his father’s voice. The face would not appear.

“She sure loved Sexton!” said Rutherford bitterly.

“Tall, an’ straight! Like his father,” said the woman. “Hair like a soft bunch of feathers! Auburn. Wouldn’ be no exaggeration to say he had a b-e-a-u-t-i-f-u-l32face for a man: straight nose, straight as a arrow! Distinguished lookin’. Humph! No wonder the girls loved him so! I ain’ ashambed to admit it. Just like his father!

“Do you know how your father got me? He stole me! Took me off the plantation by night! Almost killed his hoss ’cause he wouldn’ stop before he crossed three borders!”

“Off a what plantation did Poppa steal you, Momma?” asked a strange spectral voice. A man’s. Like somebody who was dead.

“Never you mind that!” answered the woman with deep emotion.

“You scaired to tell?”

“Yes, son, I’m scaired to tell. You, Sexton, my firstborn—you was born in Saint Louie. An’ your sisters, Nadine an’ Jessica—twins. An’ then we came west here. Your grandpa was a wand’rin’ man. Here’s where the rest of you, Ruby, Helen, and Rutherford, was born. An’ they wasn’ no space in between. My man was a half-breed!”

Amerigo gradually perceived the new face that now appeared in the reclining woman’s eyes, that of his grandma Veronica. Her skin was light, almost like a white woman’s, and her hair was long, dark brown, and straight. It seemed that a shadow of a smile lingered upon her face.

“Momma didn’ smile very much,” said Rutherford, and the gravity of his expression was softened by resignation, “except when you got her to talkin’ about Will. Then she just couldn’ hold back what was inside ’er. She didn’ love n-o-b-o-d-y else! Unless it was Sexton. She’d follow Will anywhere he led ’er. An’ I mean without complainin’!”

“He sure was a Indian, all right!” Grandma Veronica exclaimed, “but he had hair like a white man. An’ blue eyes! Even wore a handlebar mus-tache. Like Buffalo Bill. Didn’ drink, didn’ smoke, didn’ gam’le!”

“He had seven of us, Momma!” cried Rutherford. “I think that’s enough!”

Grandma Veronica’s face turned a ripe peach color. As she laughed through her closed mouth, her cheeks swelled up under her hazel eyes and a fine spray of spittle escaped her lips, while the bluish green vein that divided her forehead into two equal parts broke up the stern effect caused by her thin nose and set chin. Her yellow skin was smooth, like Cosima’s, and her long silky hair was parted in the middle, with the halves swept back and wound into a soft ball.

“An’ Momma never did talk about herself much,” Rutherford continued distractedly. “In fact, she didn’ talk ’bout nothin’ much! More Indian 33than anythin’ else. Crow, she says. But how she got to be Crow when her momma, her name was Anna, was a slave ain’ never been clear. What happened before Poppa was supposed to a come along on his hoss is as plain to you as it is to me. But he was her weakness!”

“Made his livin’ doin’ odd jobs, mostly outdoors,” said Grandma Veronica. “That’s one man sure liked to be outdoors. Will looked ridiculous pent up in a house! Had a natural way with the sick.”

“Old Will was a medicine man!” shouted Rutherford. “Hot dog!”

Amerigo tried to catch a glimpse of his grandfather, but all that came to mind was Buffalo Bill.

“No matter what you had,” said Grandma Veronica, “he’d go trailin’ off in the woods an’ turn up a couple a hours later with a little deerskin sack he usta carry around full a roots an’ herbs. He’d take off to the kitchen by hisself an’ cook ’um. Make a polstice or a stew. An’-an’—no matter what you had, if you was normal you got well! An’ whistle! Like a bird. Predict the weather just lookin’ at the sky. Fish? Hunt? Humph!”

“Her lips,” said Viola, “would always tremble in the end, and she’d start crying, like Momma. Even though she was blind! Funny how blind eyes can cry. An’ especially hers, because she always seemed to be such a self-willed woman. I’ll never forget how when we got married she …”

“She did have a strong will!” Rutherford broke in angrily. “How do you think we lived when Sexton wasn’ nothin’ but nine an’ I was a baby—still crawlin’—with five girls in between. An’-an’ Buffalo Bill walked off! Into the woods somewhere, an’ never did come back!”

“Just couldn’ stand sleepin’ in a bed!” exclaimed Grandma Veronica.

Rutherford’s expression grew bitter; his eyes narrowed and his voice quavered.

“We usta have to keep in bed a-l-l day, just to keep warm, while Momma was out workin’ for the white folks. Five dollars a week for cookin’ an’ cleanin’ an’ washin’ an’ ironin’. I sold papers on the streets when I was five, an’ had to give every penny to Momma.

“An’ rough! That evil woman was terrible! Huh! She’d say, do it! An’ if you didn’—an’ I mean right now—boom! You’d be busted upside the head. An’ no cryin’. Better not cry!”

34Rutherford looked at Viola for sympathy, but her expression was hard, insistent. Say it! it seemed to say.

“My brother Sexton was a pimp, Amerigo.…”

“What’s a pimp?” he asked.

“He kept women. You know …”

“Aw …”

“They said I wasn’ good enough for your daddy,” said Viola, “’cause I was black an’ my hair was nappy.”

“Aw, Babe!”

“But my brother wasn’ no pimp! They found they previous yellahbaby sister Ruby, who was too good to come to our weddin’, dead in a whorehouse! She was lousy! With T. B. to boot! ’Scuse me, Amerigo, but it’s the truth! Ask your daddy! She had to be buried in my dress ’cause her own sisters wouldn’ give ’er none!

“My brother this an’ my brother that they say, but they don’ never do nothin’ for ’im, ’cept beg ’im out a every dime they can git. An’ where does he have to git it from? From me! I work just as hard as he does. Every scrap of furniture that’s in this house, every crust of bread we eat, I help to pay for it! An’ him, like a fool—too weak to say no! They been diggin’ our grave ever since we been together! It just kills ’um to see us turnin’ out so good! An’ when your gran’ma went blind. She had three daughters, but she had to come and live with us ’cause they wouldn’ take ’er. We had to shame ’um! Ask your daddy!”

All the faces disappeared except those of Amerigo and his mother.

“I will love you always,” he said.

“Will you?”

“You’ll see! I’ll do somethin’ big! An’ be famous, an’ you’ll be proud. I’ll buy you a big house an’ pay for ever’thin’!”

No sooner than he had uttered these words than the face of his father appeared next to his. He whispered plaintively in one ear while his mother whispered plaintively in the other. Strains of an unbearably sad music filled the air. He shut his eyes but he could not shut out the sound.

If they say just one more word, he thought, I’ll die!

“You gotta give Momma credit for one thing, Babe.”

35“What’s that?”

“She always did love our son. More’n she loved me, even!”

“That’s true,” said Viola, “because he always loved her.”

The sad music died away, and with a feeling of relief, he once again saw Grandma Veronica’s face. It appeared as it was most familiar to him: stern, placid, with hazel eyes.

“I’ll love you always!” he whispered.

“Amerigo’s a dreamer,” she said, “just like my Will. I had big hopes for Sexton, but the women killed him.”

“It was cancer, Momma!” said Rutherford.

“You kin call it cancer if you want to. Call it anythin’. He’s dead. Ruby, my baby’s dead. She was the prettiest of them all. I guess she never got much of a chance. A pretty girl likes pretty things.

“An’ then Nadine went an’ married old John Simpson!”

“Yeah, Momma, but ever’body—white folks, too!—called him Mister John!” said Rutherford admiringly. “Yes, sir! That’s a man!”

“A one-handed, bald-headed old man!” said Grandma Veronica. “Lost it in a sawmill, they say, just as he was turnin’ nineteen. Married my girl when he was forty-five! An’ her nothin’ but eighteen. Trashman!”

“Collected things,” said Rutherford. “He had a ol’ horse an’ wagon, Amerigo, that he usta drive up and down back alleys, pickin’ up newspapers an’ rags, an’ copper an’ all kinds a lead an’ aluminum pots an’ pans—anythin’, no kiddin’! Plumbin’ fixtures, old furniture, books, bolts, screws, wire! Anythin’ he could bundle up and sell at the junkyard. An’ s-m-a-r-t! Read a-l-l the time!”

“Smart enough to collect my daughter!”

“Yeah,” Rutherford retorted, “an’ a little later he bought ’im a new horse, too. An’ now he’s got a truck!”

“An’ three kids!”

“He ain’ got but one hand, Momma!”

“Amerigo’s the best of the lot of you. He’s got two hands, an’ he ain’ forty-five. An’ he can see, thank God! Dreams wide awake, even if he don’ look like no Jones!”

“That always was a mystery to Momma,” said Viola, “how somebody can have any sense an’ not look like a Jones! If you ain’ high-yellah, with 36a little Indian-red, a little stray-brown mixed in, accidental-like, you ain’ nothin’! An’ even when the Joneses was a little dusky, like Nadine, they just had to have good or passin’-good hair!”

“No nappy heads in my family!” said Grandma Veronica. “An’ the faces are reg’ler!”

“Everybody does when the wagon comes!” said a familiar voice. Amerigo stirred attentively.

“Ain’ it the truth!” Viola exclaimed.

A woman’s face appeared and gradually merged into Viola’s face, at which Amerigo experienced a feeling of deep, almost reverent love. Aunt Rose?

Aunt Rose! That was her voice talking to Grandma Sarah! That’s her, all right! But different, younger.

Her forehead was exceedingly high. Domed and smooth. Bad hair! Smiling warmly at the part in her coarse black hair. It gave her a girlish air. Needs a pink bow-ribbon.

“She began to dye it when she was about forty,” said Viola, “when the first white streaks began to show. It’s a secret.”

Aunt Rose is no beauty, Amerigo reflected, but she has a beautiful mouth. Sort of like Mom’s. But it makes her head look smaller than it really is. Still it’s small enough. Like a little Gothic tower!

He allowed his fancy to play freely upon the features of her face. Her brows hovered nervously above her eyes like the wings of a bird silhouetted against the sky, while the eyes themselves were animated by a nervous energy that seemed to register every emotion that rose to the surface of her consciousness. They were hungry, curious, saddened by what they saw—when they weren’t too busy laughing. And they were laughing most of the time.

“She’s fat!” snapped the resentful voice of a young woman.

“Ain’t you heard, honey?” Aunt Rose retorted, “fat meat’s greasy!

“Lordy!” she sang, “Lordy look down, look down, that lonesome road, before you travel on!”

A gust of wind broke through the forest and shattered into many fragments of sound that spoke of Aunt Rose. He listened in an attitude of discovery.

37“If Aunt Rose ever lost her tongue,” said Viola, “she could talk more ’n most people just with ’er eyes!”

“Yeah,” said Rutherford, “she sure kin! She kin praise you with humor.”

“Blame you!”

Ardella! thought Amerigo.

“I’d sure hate to be her enemy!” An unidentified voice.

“Just like Ruben,” said Rutherford, “born too soon. If that black woman had a been white!”

“That sure is the truth!” said Viola. “An’ she didn’ git no further than the third grade neither. But if you could see her handwritin’, you’d think she went to college, instead of Ardella!”

“She’s a fool!” said Ardella.

“They say,” Viola replied, “blood’s thicker than water, but she’s been just like a momma to me! I don’ know what we’d a done without her. Especially when we was just married, without a dime to our name an’ no place to go after Momma died!”