Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: ONE

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

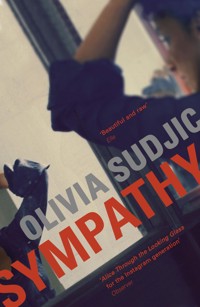

THE DEBUT OF 2017 THAT EVERYONE IS TALKING ABOUT FROM ONE OF THE MOST EXCITING YOUNG BRITISH NOVELISTS'A gripping odyssey into one woman's online-addled inner life' -- Independent'Reads likeThe Talented Mr Ripley for the 21st century' --Vice UKAt twenty-three, AliceHare arrives in New York looking for a place to call home. Instead she finds Mizuko Himura, an intriguing Japanese writer, who she begins to follow online,fixated from afar and increasingly convinced this stranger's life holds a mirror to her own. But as Alice closes in on her 'internet twin', fictional and real lives begin to blur, leaving a tangle of lies, blood ties and sexual encounters that cannot be erased.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 621

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Sympathy

OLIVIA SUDJIC

For Pat

Because the mountain grass

Cannot but keep the form

Where the mountain hare has lain

— W. B. Yeats

I wouldn’t mind being a pawn, if only I might join.

— Alice

Contents

1

I wasn’t with her when the fever started. I didn’t even know she was sick. I’d known nearly everything about her until then, and could have recalled the smallest detail of any given day, whether she’d spent it with me or not. For months her presence, and telepresence, had given shape to my new life in New York. Now, with the stroke of a finger, it had gone.

Unfollow. Intended as a symbolic gesture only, a symbolic fuck you, assuming that I’d still have a level of public access. I’d observed her this way long before we met, but it appeared that her privacy had been altered since then. Very recently, I guessed. I was alarmed by her inhibition or what it meant she had to hide. Before, anyone could find her. Just by typing her name they would get an instant synopsis of her life: the neat grid of her pictures, captioned with her thoughts and feelings, tagged with a location and timestamped. Anyone could track her progress through the city, or slip backwards into her past, to her vacations and graduations. I can’t have been the only one who’d done it so successfully. But now I was locked out. A white wall had descended, blank except for a padlock symbol.

More than her physical absence, it was this whiteout that was disorienting. There was little to suggest that time was passing. No news of her mornings or meals, no filtered sunsets or stars. As darkness fell in my world, the light from hers tormented me, remaining the same bright hospital white. I butted my index finger repeatedly against the wall, but her defiant little mouth, just visible in the porthole containing her profile picture, turned my symbolic gesture back towards me: Fuck you. It was all symbolic. I touched the mouth; it was hard and would admit nothing. Her face was hard too. It denied, or felt nothing. No amount of pressure made any difference. There was nothing I could depress except Follow or Back. I couldn’t decide which, so I waited, hoping that the unhappy choice would be taken away. Sometimes I would cover the glare with the palm of my hand, cancelling her light completely by squeezing my knuckles together. I’d count out sixty Mississippis and then flare them open again, hoping with this expansive motion to have magically sprung the lock, or to discover that the wall was only a temporary measure and she’d now restored her previous settings. When she did not, I tried more inventive routes. Rather than typing in her name, like any fool, I interrogated other names I knew — the names of her friends — pressing on every back door I could think of for a glimpse of where she was and who she was with, hoping to find her sheltering in one of their pictures. Not one of them had seen her, or if they had, they were hiding the fact. Or she was hiding somewhere in that labyrinth of other people’s lives, but behind the lens itself.

It didn’t take long for my resolve to weaken; then, after I’d admitted defeat, tapping Follow again, the time spent waiting for her to approve my request passed impossibly slowly. For whole minutes I convinced myself that it was the best thing to have happened, that this was in fact the only way out: to know nothing more about her from now on. It was useless, however. I knew too much already, and for long hours in between those minutes I tortured myself with grim fantasies — what was happening behind the wall as I waited for reentry.

Follow, once white, was now an arresting grey, the word replaced by Requested. I felt this new word did not convey proper urgency. For a start, I did not like the past tense. I glared at the word as I lay in bed, certain that my envoy was not requesting hard enough. I wondered how I might take back control of the situation. When we had spent rare nights apart before, I’d kept our message thread open, in order to watch her name waxing on- and offline in the grey bar at the top of the screen, pressing it every so often to keep it lit. By doing this I’d felt as though I had her next to me, as if she lay beside me breathing, but trying that trick then felt more like lying beside a corpse for comfort.

When I wasn’t watching the white wall, I watched the grey bar. At least there time moved on. It didn’t tell the actual time, but how long had passed since she’d gone off-grid. I wanted to breathe in the same atmosphere as her. I opened the windows as many inches as I could, felt the currents of air that moved between the tall buildings, and imagined liquefying them, creating a hydraulic system between us, so that I could position and push her finger down just by levering mine above the button. Once, I felt sure I’d seen her status morph from last seen to online and from online to the pendulous typing: a sign of life, like steam on a mirror. Then I had blinked hard, and again the grey bar, the headstone above the message thread, confirmed that she was not.

I waited for her to appear for so long that occasionally I had to turn over, onto my front, and lower my device-holding hand to the floor to steer the blood into my fingers. If I managed to fall asleep, my mind pinballed through possible encounters, following her to every intersection of the Upper West Side. Depending on the intensity of my despair, the streets either connected or separated us, and though I barely moved, each time I woke I was exhausted, fingers pruned with sweat as if I’d spent the night stalking the fifty blocks between us.

This limbo period taught me everything there is to know about the terrain between longing and revulsion. Where they met, I felt sickly warmth seep up from the mattress. Whenever I found it, I had the sensation, like a neck twist, a violent muscle spasm, of having briefly possessed her. Just there our bodies snapped into alignment, and it was, for an instant, me doing whatever she was doing while ignoring my Follow request.

From the limited amount I do know about her activity then, the sickly heat makes sense. My intelligence came later, from the doorman in the building where she lived on West 113th. He reported that by the time she’d arrived at the hospital, two blocks away, as a walk-in with a high fever, a parasite had bored into her brain. He explained that it had all begun, like most things covertly bent on death, with “flulike symptoms,” and the first doctor had dismissed her on that basis. Sent her off to buy a stronger version of Theraflu. When she made her second trip, it was by ambulance. The doorman had called 911 himself. Ambulances, he informed me gravely, are usually reserved in America for the very unconscious or the very rich, but he had reasoned that she was both.

“It probably began its life’s journey at the bottom of the ocean, in a crustacean. Found its way into something like a frog, and from there into something like a snake, and then a bird —”

“Or,” I interrupted, with a croak, “some other creature.”

He studied me for a moment. I had barely spoken to anyone in days, and it had become a strain to keep my theories to myself.

“Right,” he continued, “before being eaten or petted by her. She loved cute stuff, right?”

“Right.”

“The demon.” He rolled his eyes and I nodded. Her cat was a menace, it was true.

After her operation, she was moved into a room in the ICU, with a prime view of the Hudson. It would have been the first day of October. I remember the air outside was still warm, hot in the sun. The summer, the summer of us, lingered in the soft light and the thick end-of-day heat, but she retained little memory of any of it. The latter half of July, all of August and September had been disemboweled with the removal of the parasite. She first met me in August, and she later assured me that my part in it all had either been eaten up by the parasite or burnt away in the operating theatre.

In a story she wrote after it happened, some time after I left New York, she says she remembers nothing but waking: a “burning sensation,” the “wet bloom” of her own eyelids, gluey from surgical tape, seen from inside as she “swam into consciousness” in a bright room. The memory, suspiciously literary, excludes her mother, who had travelled there from Tokyo to keep a vigil. Either the wet bloom is made up and she remembers nothing about waking in that room, or she has purposefully edited her mother from the scene. The mother was definitely there. She even took a picture of her daughter coming round and beamed it back a generation to her own mother, at that moment still sleeping in the curve of their ancestral archipelago. The picture was accompanied with the word Waking! in Japanese.

Kakusei!

Back in the lobby of her daughter’s apartment, as she returned the spare key, the mother showed the picture to the doorman, plus an x-ray which revealed the strange looping path of the parasite. She thanked him for all his help. He’d saved her daughter’s life, no doubt. She would be discharged soon. It was only two blocks for her to walk back, or she could take a cab. She might need help, more than usual, in the coming weeks.

You will have seen the Kakusei picture. It ended up in the news. It isn’t flattering. Her determined face is flushed, the jaw juts out, though I suppose her beauty is a fact so absolute that vanity is beneath it. The picture is now the first to come up when you search for her. Mizuko Himura. I have set a million traps for that name. Whenever she does or says anything, or anyone else does or says anything in connection with her, across whichever ocean, the name reaches me in a Google alert. Each time I reel in the net, experience rapture for about one second, and am then overcome by acute nausea. I will read without breathing, scanning to see if any of her words are about me, or secretly addressed to me, and feel a creeping mortification when nothing stands out and she slips back into the water. Though I am still hoping for a message, even now that more than a year has passed, I have to assume that the omission is the message, and that her long silence contains all the answers I need.

Looking at the pictures of her taken since, I can tell something has shifted. The charm has become strange — stronger, if that’s possible — though that might be the effect of distance, or professionally applied makeup, or my reading into her face what I know to have happened, or all of the above. Her features appear somewhat dismantled, less symmetrical, as if you are looking at the remnants of something perfect but you can’t properly remember it whole.

I still don’t know how she really felt about me. I’ve gone through all the things I kept; they’re inconclusive, flotsam and jetsam that could mean anything or nothing. I am sure there is something very deep, lying far beneath the surface, which, if disturbed, maybe even provoked, might finally come up for air. I used to be able to summon things that way, pulling things towards me on invisible strings, making the sky dense, a febrile blue screen shivering with all that I wanted to keep close. In fact, right before I left for America, my mother had passed the power on to me. A singular inheritance. She’d poked her head into my bedroom, where I’d been holed up, packing relentlessly for weeks. I’d grown used to stepping over and around two halves of a suitcase in the middle of my floor and had forgotten that at some point I’d have to a) close and b) transport it without assistance. After a period of silent observation, me furiously folding things without looking up, she advised that I try to “live lightly” in New York. Back then, knowing nothing of what awaited me, I’d assumed this wisdom was aimed at my suitcase, split open on its back, leaking onto the carpet my too-difficult books (Baudrillard, Deleuze) and too-careful ensembles. Then she’d pinned me to her chest, the first hug from her I could remember as an adult, and I felt her press the power into me. It slid like mercury, tingling in my fingers and toes, giving me a new sensation of their weight. She’d never lived lightly herself, of course. She suffered from incurable apophenia. “In Manhattan,” she said, “either you need to be light, so light you float above the city as a solitary spore, or” — and this was the sudden flipside to her warning, the part that lodged in my mind — “you have to be really, really heavy, pulling everything there is towards you.”

2

When I look at the Kakusei picture of her in the hospital, I remember waiting for her to wake up the first time I slept in her bed. It was August. I lay there for hours, until the morning sun that streamed through the window became painful, my body on fire but unable to move. Very, very slowly, I turned my head so that I could see the back of her neck. The clasp of her necklace had left its imprint like two tiny teeth marks.

I tried to remember all the things, each little link in the chain, that had brought us to this point, this place, my eyes boring into her back, her outline so much sharper than in pictures. It felt strange that I couldn’t stretch out my hand through her body, push it out the other side, or turn her over in my palm. Until then, having spent hours on end, day after day, sliding my finger through her pictures, I had thought of her more like a liquid or a gas, but in fact she was a solid. It was strange too to see her from new angles. In short, to be so close. I don’t mean in the way it is to go from strangers to lovers. I mean the exact opposite, in fact. It was more like I’d gone from lover (intimate, easy in her company, despite her never knowing I was there) to stranger. She didn’t know me at all, and that felt unreasonable and surprising. I also found it hard to accept that the Mizuko I’d known in multiple miniatures was one physical person. I suppose it would feel the same waking up in bed with Jesus or Father Christmas, or any long-dead figurehead of an ancient cult. You know every word of every doctrine off by heart and then you see their toenails, gums, and vertebrae, not in pieces but all held together, and it’s hard not to lose your shit.

I’d trawled through all the comments under her pictures, mainly from girls she didn’t know but who, like me, had noted how imperceptible her pores were and praised her skin for being like a baby’s. I’d also read the ugly phrases like “assimilated Manhattanite” and “enfant terrible of a Japanese banking dynasty” in various short profiles of her in trendy literary magazines. There seemed to be more of this type of thing online than her own writing. It’s true she didn’t work that hard, or produce much writing in the time I knew her. Back then she spent most of her sweet time not go-getting but posting pictures of the things she wanted and liking the pictures strangers posted. She rarely said no to people, but not because she was actually nice; she just knew a way to make everything work to her advantage, shaping it into something she could use, usually in the brushwork of a story. There is probably a precise Japanese term for that kind of person. I should have asked.

There was a time I could just turn around and ask her a stupid question like that because she was literally right there. I can hardly imagine it now. Very occasionally I feel like she is standing behind me, watching me struggle for the words, or daring me to use them, and sometimes as I type I get that feeling that comes at night when windows become mirrors and you begin to sense that you are being watched. That your bright interior world is being inspected by eyes you cannot meet. Whenever it comes over me, I stare aggressively at my reflection so that whoever is out there will think I’ve spotted them. At the moment I live alone in a studio flat in Wood Green, England, an eerily lit subterranean bowl that can be peered into from street level. In case someone is there, hidden by my reflection in the dark glass, I raise and lower the blind with mysterious purpose and stare angrily at myself in the window, but really through me and at my imagined stalker.

But how did I get there, in bed beside her for the first time? That morning, August 11, I felt no different, morally, from the way I had as I’d walked to her apartment from the sushi restaurant the night before, August 10. Just following, not really knowing where I was going; one of the few things I had not known about her already was her exact address. I had obediently trotted from one thing to the next without feeling like I was moving much. It felt that way for all the time that I knew her really, until I got to the end and looked back. When I look back, of course, it goes way, way back.

Mizuko was thirty-two when I discovered her that summer at twenty-three. I have the email that dates the discovery as July 23. She looked like a child, and certainly younger than me. We met a couple of weeks later at the Hungarian Pastry Shop opposite Saint John the Divine. In June, I had moved from where I’d been staying on the Upper East Side into her neighbourhood, Morningside Heights, up by Columbia University. I already knew the majority of what I still know about her before we met. She was born and grew up in Japan. Her grandfather founded Himura Securities. Her mother had her own company back in Tokyo. She had lived in New York since turning eighteen. She had always been sure of what she wanted to do in life, and now she was a writer with representation, teaching a number of classes in the creative writing MFA programme at Columbia which she had taken herself a few years previously. Her most successful short story so far had been “Kizuna,” or “The Ties That Bind.” It was the one I liked best. Back then she was working on a novel, tentatively titled Kegare, which she translated for me as “Impurity,” though I was never allowed to read it.

“Origin stories make us feel secure; untangling them can undo us.”

That is the first line of “Kizuna.” It was also the first of her stories I read.

Sure, I thought. Yup. I started to imagine that those words were even written by me. Reading about her life felt like pressing my two hands together. She seemed a perfect match. I made her into my origin story — a way to explain myself to myself, as if she alone would give me a reason for being in the universe.

New York is my birthplace; that’s why I went back, which is how I met her. I went there hoping I’d fall into place. It was spring 2014. The Malaysian Airlines flight had recently gone missing, and on the flight over I was terrified I’d disappear into grey ocean and be lost forever. As a result, I did some of my best existential thinking on that plane. Suspended, disconnected, stationary, yet hurtling through the sky at hundreds of miles per hour, unable to effect any change at all.

I remembered when I had first heard the words what goes up must come down. My mother discussing some kind of comeuppance. Now I think of my flight to JFK and the trajectory I have been on since: the apartments on floors that got lower and lower to the ground, until I moved into a basement. What goes up must come down was a maxim I’d heard my whole life, so often and in so many different mouths, like glass made fuller but dull by the sea. On the plane I understood it in a new way, a way that blew my mind with the simple, universal truth of the words. When the captain announced that we were at last making our descent, I reacted to the inevitable news as if I’d been called on to land the plane myself. Although my view was thick white cloud, I had to screw my eyes shut. When the seatbelt signs went off and each row broke into a frenzy of personal electronic noises, I was the only person who remained in my seat. I stayed until the last passenger had passed me, and read my landing form over multiple times, digesting all the forbidden articles. Fruits, vegetables, insects, cell cultures, disease agents, snails, soil. With great care, I copied out Silvia’s address from one of her envelopes, even though I knew it by heart. I checked the form again. Gambling? Yes. Violent pornography? Yes. Moral turpitude? Not quite yet.

In the end I outstayed my tourist visa by some months (four), accruing what is called “unlawful presence,” meaning I am barred from reentering the United States for three years. Though the customs hall was heavily air-conditioned, I was sweating, and on being asked the purpose of my visit, I blanked. Being born in New York, I had once possessed a U.S. passport, but my mother had claimed that for tax reasons I should give up my American nationality and get a British passport to match hers. The man at the desk took my picture, then feigned interest in the gap-year stamps I had collected, I suppose to signal that he was more human than his outsize shoulders suggested.

“Cambodia? They eat a lot of crazy things out there. Seems like they eat whatever runs past them.”

“Yes,” I said with a big smile, even though I do not hold that view myself.

I was ready to mimic, to learn customs, to please.

Reacquainted with the enormity of my suitcase, I decided not to try the subway just yet. In the back of a cab, a ribbon of text slid from right and vanished left at the bottom of a screen set into the partition, bringing breaking news of an escaped elephant, followed by a drive-by shooting in Queens. Because the language was the same, I was not prepared for just how foreign-feeling everything was. I had to tell myself that this was a place once populated by Native Americans, where there were arrowheads in the ground. I reminded myself of it often during my time there. Every time something happened to make me feel like an alien, I thought about the Native American arrowheads. A certain sensibility in the soil which slipped into the water that came out of the taps, tasting so different.

We rode most of the way to Manhattan alongside a law enforcement vehicle, a van that said CORRECTIONS in blue along its body. It was the kind you expect to see John Malkovich jumping out of and then fleeing into the graveyard that bordered the road. I was immediately transfixed. Everywhere I looked I saw movies. There were backyards, garages, solid-looking porches, clapboard houses. The words downtown, crosstown, uptown, also solid as tree trunks. I had brought a little brown journal with me. Silvia, who was in her eighties and would be my host, had recommended the idea, suggesting that, like saving money, it might aid my recovery. I turned to the first page and, interested primarily in lighting effects, wrote: beautiful light on Van Wyck Xpwy, oily afternoon sun, anointing my forehead. Mizuko later mocked me when I showed her, but that was exactly how it felt: an ancient sunburst that had anointed so many before me, bestowing on them a second, or third, beginning.

Outside Silvia’s building, the air was damp and delicious, with a diffuse smell like a mysterious cinema snack — a prickly, popcorny breeze that made me feel light-headed. I forgot to tip. I realised as I shut the boot, exhaust hot through my jeans, that I was ready either to cartwheel for miles or to collapse where I stood. Her building was on East 72nd, constructed from glass and mirrors, and looked after by three identical men — all, I think, called Tony — who supposedly took turns but were always huddled together behind a desk in the lobby.

“Go right up,” they chorused. “Twenty-three, apartment A.”

It was an efficient lift. My stomach lurched and I put my arms out behind me. I wanted to stop off at another floor so I’d have more time. I hadn’t thought of what I might say as I crossed the threshold. I had all the big conversations rehearsed but not the start or the build-up to them. At her door I knocked a few times, but there was no answer. I considered returning to the lobby but then tried the door, and it opened.

“Hello?” I called, gripping my case. “It’s Alice.”

I waited to be acknowledged. An intense heat emanated from within. Slowly I made out that the hall was lined with mirrors, glinting darkly, with Persian rugs along the bottom. I took cautious steps, calling Silvia’s name. It occurred to me that it might be a hoax. There was a chance I’d been writing back and forth with a very wise and supportive Nigerian scammer who had for two years been effecting the typewritten script of a grandmother with cancer. It was plausible. My mother had once received a beautifully descriptive email explaining that a Nigerian astronaut had been left on the moon since the seventies, was in good spirits, but was ready to come home if she could help. Surely, I told myself, even such creative people did not deal in typewritten letters.

The first door I came to was slightly ajar. There appeared to be a figure beneath a sheet laid out on the sofa. I’d been taught not to disturb sleeping figures and so retreated. After some minutes I decided I should make a noise and located a bathroom. It was covered floor to ceiling in framed photographs of Silvia and her late husband. The area around the sink was littered with Spry cinnamon mints, and there were a few different iterations of a plastic device, like a larger-than-normal turkey baster, perched around the bath. I flushed the toilet, but the flush was too gentle, barely a whisper. When I emerged, the body was still sleeping.

I tiptoed through the rest of the apartment. It felt like I had intruded onto the set of an American sitcom, and I was surprised to see that each room actually led somewhere, with enormous windows so that you could see across the city for miles. There were three bedrooms, two with en suite bathrooms. One had clearly been a man’s and was now annexed as a study. One was filled with boxes. The other was Silvia’s, though she never slept there and later told me I should sleep in it myself because the bed had the best mattress and she always slept on her sofa anyway. There was a living room that was also a dining room. It had saloon doors into a kitchen, the guest WC that I had used, and then the den that Silvia was currently sleeping in, with a television playing TCM on mute. Back in the living room, I picked up a pair of binoculars from a coffee table. The city was still there. After twenty minutes, I sat down on the living room sofa and immediately fell asleep.

When I woke again, the sky was dark, but the orange glow of the streetlamps radiated upwards. Silvia was standing in front of me.

“Who’s that?” she said, peering.

“Alice,” I said through other words in my dream.

“Who?”

“Alice. Hare,” I qualified. “I’m here.”

“You’re not supposed to be here until tomorrow.”

“Oh,” I said, starting to right myself.

“I didn’t want you before tomorrow. I’ve had an operation.”

“Sorry,” I began, trying to stand up.

“Okay,” she said, and shuffled back into her den.

I listened and waited, blinking in the up-lit dark and feeling that everything was upside down. After a few minutes, in which I could hear her fall asleep again by the resumption of shallow breathing, I lay back and tried to breathe deeply, because I could feel that I was about to get locked into the anxiety attack that had threatened at various points on the journey every time I thought about the plane that had disappeared into thin air. I felt unreal, like a phantom in her apartment that she’d walked right through. My breaths were getting shorter and faster, as if I were sucking on a straw with no opening, until I felt my lungs expand much too much, so that when I tried to exhale it felt as if they had stuck together and were tearing from the effort of pulling apart again. Then I was crying, gulping and crying, also then roaring. Then, when no one came, the tears stopped and I was very still and totally quiet, like an infant silenced by the profound shock of something shiny reflecting on the ceiling. Except all that had happened was that the sound of the roads far below had made a pin drop, locating me, reminding me where in the world I was, that I was really there, and it had stunned me.

I settled back onto the pillow and recalled the start of my correspondence with Silvia, or the scammer pretending to be her, nearly two years before. July 2012. The summer before my final year of university. I was ploughing through a reading list outside on a khaki canvas camp bed from the army surplus store. Most of the furniture we owned was portable in some way. I came inside when I heard shouting. My mother was standing in front of the television set. We watched a room full of physicists officially declare the discovery of the Higgs boson. Peter Higgs, a kindly-looking, beaky-nosed man, shed a single tear. My mother cried too, much more than Higgs. “Okay,” I said, patting her. “But it really doesn’t have anything to do with us.”

A week later I got the letter from New York, with a postmark dated the day of the discovery.

Dear Alice,

So it turns out we are immersed in an ocean. No doubt you will have read about the discovery of the Higgs particle. It makes my brain ache to think of the largest machine — they keep saying it’s the size of Chartres Cathedral — finding the smallest particle in existence. Do they talk about it at your school? Forgive me, you are over that by now. Are you still studying? I wonder what sort of girl you have turned out to be. I last saw you when you were very small, and I assume now you are much bigger. I suppose you will wonder why I am contacting you again after so long. Well, I don’t feel like going into it much unless you want to know. If you do, write back.

Yours truly,

Silvia Weiss

3

I had little trouble appropriating parts of Mizuko’s origin story because in practice my own origin story didn’t belong to me, and it was always evolving. If I challenged anything — dates, names, places — my mother would respond not with an answer but with a question, like why didn’t I go and find my real parents and leave her in peace? She meant my birth parents, and each of us knew that was impossible. One was dead; the other had been in prison but was maybe dead by then too. I knew almost nothing else about them.

Memory is our first tool. We learn the face of whoever feeds us, and other things — less corporeal. We remember feelings, or persistent doubt. Then it starts to trip us up, starts to manipulate and mess with us. I suppose you could say I went to New York that spring because I wanted to escape, in England, what Mizuko’s therapist had named a toxic cycle of self-doubt. I wanted a single, coherent narrative to explain who I was and what it was I was supposed to be doing.

In fact both my mothers were possessive of facts. With my second one, every detail, if you record and compare, is contradictory. The main focus is always her absent husband, my second absent father, Mark. Sometimes he is a deserter, his memory despised and insulted; other times he gets to be a kind of destiny that is worshipped and wept over. How I fit into the picture has continually shifted. I have been a marriage-saver and a marriage-ruiner. The one line she’s held on to throughout is that I will mess everything up if I try to lay my hands on any part of it. I’ve told her practically nothing about last year.

When Mizuko asked me to sum up my childhood in a word, I said claustrophobic. Susy would never ever, she assured me, let me go. But I should have said contradictory, since at other times it was the opposite. I would wander around our cottage on my own or settle secretly in the attic, where she kept countless fragments of fact in unpacked boxes. The sheer volume of information was overwhelming, rendering it close to useless, and I think she intended it to be, to put me off searching through it. It would have taken a million robots a million years to reassemble what had really happened to us from looking in our attic.

In her letters, Silvia gave me her version of events.

I’ll start with when you were born. Manhattan in 1991. I called you Rabbit. That was what I called Mark when he was a little boy too.

Rabbit’s stuck, at least for me, in my head. I often say it aloud to myself, or aloud but in my head. Rabbit. I prefer it to Alice Hare, and I was in heaven when Mizuko started calling me Rabbit too.

You might have had another name before Alice, but your real mother fled with that detail (among others) from the maternity ward of Lenox Hill Hospital in her green gown

— I imagine her balloon-belly leading, bottom winking —

to surprise a red Moishe’s moving van on its way downtown. She was smashed like a watermelon before anyone could ask what, if anything, she might have had in mind for you. Neither, having a flair for surprises, had she told your father you even existed. Himself, disdaining both women and authority, would most likely not have followed orders anyway. He was incarcerated in Baybram Correctional Facility for crimes that require, for their successful undertaking, something as poetic as an “abandoned and malignant heart.” It became clear that your real mother, who could not have afforded even your delivery, had no plan for you that the state could execute, though the authorities raked through her few personal effects for a clue.

I know, from what Silvia told me, that inside the steaming belly I had so recently exited they found only collard greens, string beans, whiting, and schnapps, and that those who saw the accident reported that my mother’s last words were barely intelligible, seemingly addressed to herself: “Nigger, leave me alone, let me be. My son will blow your brains out.”

All the best stories begin like that, Mizuko said when I told her. Lucky you.

You were put up for adoption. My son, Mark Hare, and his wife, Susy, took you in. They had a name ready: Alice. I was there when you were handed over, a tensile ball of fists and fuzz, a lifetime of fairy knots. They were older than normal parents. Mark was a physics professor, Susy was an illustrator, at least on the adoption forms, and they lived near where he worked at Columbia University in Morningside Heights.

This is the bit I had heard over and over from Susy. I knew they met there as undergraduates, during the student protests in 1968. I’ve been told the story so … many … times. I think everybody who has ever had even the briefest encounter with my mother knows it.

Their first conversation was broadcast on the student radio station, WKCR. Susy, then Susannah and eighteen, an earnest freshman from England, interviewed Mark.

“Very tall, strong arms, one raised in a fist like a divining rod” (the divining rod, a staple, is one of Susy’s few landmarks in the story). It pleased me that when I fact-checked Silvia’s letters, all their details appeared online, rooting it in the real, repeated almost word for word. It made Silvia feel comforting, as if with her I finally stood on solid ground. Back then I had no reason to mistrust the medium; it seemed reassuring, impersonal, objective, with no particular bias or axe to grind. Google was the arbiter of truth.

Susy wanted student voices for her “Columbia in Crisis” segment. Most of the Class of ’68 used their graduation as a platform for another protest. The ceremony was conducted at Saint John’s that year, and many students hid radios under their academic gowns, silent until they burst into Bob Dylan, when WKCR played “The Times They Are A’Changin’” and the students marched out into the sunshine.

They got married in 1976. Your mother looked like a dessert. Mark began working toward becoming a professor at Columbia. I guess he felt claustrophobic, having been born, raised, and then worked his way up in academia within the same two-square-mile pocket of Manhattan.

Susy always says she knew he was the man she would marry right after she first slept with him. She had gotten up, dressed with her back to him where he lay in bed, then sat on his one armchair in his poky student room. As she sat there, watching and waiting for him to wake, she got that intuition that her period was about to arrive, slightly ahead of schedule. She leapt up at once, but it was too late. Mark refused her offers to recover his chair, saying, perhaps still high or half asleep, that it was a marker. A stain that made her part of the furniture. I have never heard her tell that story and not found it slightly creepy, but she always uses this anecdote as if it were a litmus test of good masculine character. He sounds nice, she will say about some man, but you can see she’s thinking he wouldn’t pass the period-stain challenge like Mark.

After he finished his PhD, Mark accepted a position as a theoretical physicist at Columbia. A theory emerged to explain the elementary architecture of the universe. He began focusing on superstring theory, and gradually M-theory. M stands for mother of all theories, magic, mystery, or matrix. It is an adaptation of superstring, a simple equation by the standards of particle physics, that, if proved, will “reconcile what we think of as incompatible things, explain the nature and behavior of all matter and energy.” And he became, shall we say, preoccupied. Susy (Mark was the one who contracted her from Susannah to Susy, the abbreviation of superstring theory) was in awe but could not work him out. I guess women love mystery. Trust me, you want to go for a nice, safe one like my late husband, Rex. I made that mistake with Mark’s father. Your mother doesn’t like there to be things — any things — that exclude her. Physics was like a secret language between Mark and his friends. She used to make jokes, funny for no one at all. Things like, “As a physicist, he should be taking more interest in the physical, or in patterns which repeat, and small things, like babies.” She raised it around so many mortified acquaintances and waitresses that, because Mark would do anything to avoid a scene, they began trying for a baby even though it wasn’t the right time with his research. They tried for four years without success.

I knew a lot about their sex life already, because, in that area, at least, my mother has no filter.

I remember the year it became an issue, when I sent Susy to a doctor, because it was when the Chinese loaned two pandas, Ling Ling and Yun Yun, to the Bronx Zoo. I had decided I wanted a grandchild by this point. I guess now that it seemed possible I might not get one. I did a lot of reading about the mating process the zookeepers were trying to facilitate. I think pandas lose their libido if a human walks through their enclosure, much as a human would if a panda crashed through the bedroom.

Susy mentioned the pandas too. Mark was a kind of Ling Ling, the male panda. To get him interested in mating, Susy would create a set of imperceptible conditions — the right temperature, the right light, the right meal — and to boost the chances of this rare, involuntary urge — the Great Hump Day — occurring at a moment when she could make use of it, she barely left his side.

Though she went with him pretty much everywhere, even to work, where she would seat herself in a library near his office, she was oblivious to him. She had wished so hard, for so long, for a particular future to manifest itself in a blue cross that the blue cross overlaid Mark’s face.

I know the feeling.

Mark said to me that whenever he woke up, Susy was lying beside him, already waiting, with her eyes wide open. She kept talking about how they would soon be the Three Hares. That’s the famous symbol of the three hares chasing each other, something Mark had explained to her once, early on, before he knew how she would turn it against him, as a classic example of rotational symmetry. My only input was names. I always said it would need to work in a crisis, over a loudspeaker, and in a foreign accent.

When I stayed with her, Silvia could always be counted on to summarize the nature of something about to happen so that then there was little need to actually do it. Susy still wanted to do it, and had dutifully chosen a name with an eye on death, destruction, and crisis management.

I made a list of all the possible things Alice might rhyme with if yelled down a busy street, and it didn’t appear there would be many emergencies where you would mistake Alice for palace, malice, or chalice. Susy stopped going to all the expensive doctors I’d sent her to. She believed by going to fertility doctors she was pulling infertility toward her. Instead she read horoscopes and did Tarot cards. The paved footpaths in Riverside Park were riddled with cracks. It was all code. I remember she even bought that candy that comes with messages inside and left the pertinent ones on Mark’s side of the bed, which went undiscovered and were slept on, leaving troubling brown stains on the sheets. My cleaner then was Mark’s too, and she used to complain about it all the time. But the big sign came when she was standing by the Alice statue in Central Park. She got talking to a young woman who swiftly became her friend, confidante, and then, despite Mark’s and my attempts at intervention, surrogate. Susy could befriend women at the speed of light. I always say that those friendships are more like falling in love and always finish as quickly. And of course the surrogate ended up miscarrying the first Alice. So Susy was forty-one by the time she finally brought you, Alice II, home in a Moses basket.

This is my favourite part of this particular letter …

By then they lived on Claremont Avenue in professorial housing. It was covered in snow when we carried you up the steps of the building. It was January 19, 1991. I have a Polaroid I’ll show you when you get here. In the hour between leaving and returning, there had been a power cut and water had flooded everywhere. The long, dark hall was knee-deep, the elevators were out of service. Mail had floated out of an open mailbox on the bottom row, spooling all manner of personal information around the faux plaster columns. I hated that apartment. I remember Mark looking so depressed, and I made, in retrospect, an ill-judged joke like “Don’t throw the baby out with the bathwater.”

I had to admit that it seemed a lot of what Susy had told me about that particular moment appeared to be true. Once I had even found the note that my mother had said was pinned to the noticeboard in the entrance when they got home to the flood:

Dear tenants, someone has a faulty flusher in their toilet. If you notice your toilet is not flushing properly, or if you hear noise when you flush, please notify the super. Thank you, Ramon

Susy told me that Mark smiled, took the note off the board, folded it neatly, and put it in his pocket. This was normally the thing she would have done — something that seemed out of the ordinary and was perhaps a sign — but she was carrying me in the Moses basket and had no free hands.

“What are you going to do with that?” she asked him.

“Mark this day.”

Then he had apparently started humming “The Power of Love” in the flooded hallway, lined with broken columns just like in the music video for that song where Luther Vandross is up to his shins in water and the screen crackles with electricity bolts, suggesting an invisible field of love permeating a Romanbath-themed nightclub.

At first, when I was a child and my mother used to recount the homecoming, bringing it into sharper relief each time until you’d think it had happened the morning of her telling it to you, I thought it was a story about how happy Mark must have been to finally be a father. That’s the way she tells it. Even before Silvia got in touch, as I grew up I realised that by that point he was a forty-four-year-old particle physicist, and so gradually I saw that singing Luther Vandross was another kind of sign. He was losing it. My arrival meant he could finally leave the city, where he was cracking up under the conviction that he was wasting his one chance to be great. For him to take the note meant that, like Susy, when he wanted something badly, any rough-edged, fragmentary thing became as smooth and unequivocal as an arrow.

Mark was by then part of a team setting up the SSC (Superconducting Super Collider) in Waxahachie, Texas. It was, if you know nothing about physics, supposed to have been what the Large Hadron Collider in Geneva later became, except the American version, of course, was going to be ten times more powerful and hunt the Higgs boson “ten times faster.”

In 1988, the year of that first, miscarried Alice, the area around Waxahachie was chosen, by a committee that included Mark, as the site for the collider. He was then enlisted to convince coastal academics to move there. Young physicists had followed, not yet in his footsteps, but his directions. Settlers in big white sneakers, mavericks in Hawaiian shirts. Though he still lived in New York, he had been spending more and more time in Dallas (Susy, for national security reasons, was forbidden from accompanying him) and less and less at Columbia or the Morningside Heights apartment, where Susy occupied herself by drawing. Her condition for relocating to Dallas had been that they would first adopt and that she and Mark would write and illustrate a children’s book together, Alice in Dallas, which would make particle physics accessible to three- to six-year-olds.

Seventeen shafts were sunk and fourteen miles of the tunnel bored out of Austin chalk before the site was abandoned. Congress pulled support, canceling funding, citing fears about committing to its projected cost. Many physicists went to Wall Street; a few who remained got involved in ranching.

That’s from an article Silvia showed me. Susy sometimes says that too, wistfully, as if cattle might have been the answer. Other times, depending on her mood, she speaks self-importantly about her sacrifice — as if the fate of American science, the discovery of the origins of the universe, rested solely on Mark’s permanent physical presence there.

When it was cancelled, Mark felt betrayed, not, I now know, by Congress, and not by the physics community, and not, Silvia assured me, by me, but by Susy. If she hadn’t made him wait in New York until they found me, if he had been there, in the field, sooner, he was sure the project would have succeeded. I’m sure he felt guilty. Not for us, but for all the other families and lives he had uprooted, abandoned in the middle of the desert, and exposed to early failure.

In 1993 he and Susy came ingloriously back to New York, with you in tow of course. You had just started talking. You came right back to the same bit of Morningside Heights, but his Columbia accommodation had been reallocated in your absence. For a year you all stayed in an apartment owned by one of Mark’s friends — another professor, who at that time rarely used it — in the area. Someone had used pieces of boat interior to establish a new life within the building at some point, so the apartment looked like a 1930s art deco ocean liner inside.

I imagine this to be the kind of unique interior that can only have come into being when one of the residents came into the possession of an ocean liner and didn’t know what to do with it.

It was possible it was supposed to thematically connect the building with the Hudson, but it bothered Mark that there seemed to be no explanation for your new surroundings. I remember when I first visited you there, he was sitting in the middle of the apartment, sleepless and malevolent-looking. He didn’t look like himself at all. All of the rooms intercommunicated, so you could see from the hall to the living room and from there to the dining room. He had the central vantage point on the couch, and he kind of glowered at me and didn’t say anything. It did not, I told him, as usual trying to make light of the situation, match the buoyancy of the building. He ignored me. I could see it was this deliberate sabotage. He was in opposition to everything around him. None of it made sense anymore. He had gotten used to seeing his equations overlay every surface, and the blank white walls held no meaning for him. He moved with his eyes only, conversing with every object, sometimes as if he were trying to sink it, sometimes as if he were just trying to restore it to its original course, somewhere out to sea, by force of will.

When its rightful occupant needed the apartment back and we had to disembark from the ocean liner, we moved in with Silvia.

Just when I got you settled in, Mark revealed that he was accepting a job at a bank in Tokyo. Trading desks, he told us, wanted quiet, clever men who could bring scientific theories to chaos. He had, apparently overnight, made up his mind to quit both physics and America.

Susy tried to ship Mark’s armchair — the dark period stain had been hidden under new upholstery — but Mark was no longer available for compromise. He had already embraced Japanese minimalism, and the chair could not be part of our ascetic life there.

The bare minimum was shipped ahead, and you three followed a week later. I came in the taxi to the airport. I remember I hummed a kind of hymn to Saint John the Divine, an unfinished monument that to me embodies all the qualities I so admire in physicists who wait a lifetime for a theory to be proved. We sat in silence and stop-started, making incremental thrusts along 125th Street, just as schools were being dismissed. As we passed the Apollo Theater, Susy turned to you — you were sitting in between us, Mark was sitting in the front. She looked at you with big, meaningful eyes, of course addressing me and Mark, and said something like “Feels like moving to the moon, right, Alice?” And I remember you began to cry. Such a heartbreaking sound that I could have cried too, but I couldn’t because I was so angry. I already blamed her. If I’d known it was the last time I was going to see him, I wonder how I might have tried to stop him, what I would have said. I go over emotionally manipulative maternal speeches in my dreams. Do you know Volumnia, Coriolanus’s mother? I remember the last “conversation” Mark and I had pretty well, because we barely spoke and your mother did most of the talking with the taxi driver while we listened and I tried to tell him by looking into the curve of his right ear that I was forbidding him to leave even though I was coming to say goodbye. The driver had polite questions, phrased as if all four of us were going on a happy vacation, and Mark left Susy to field them from behind. We were given a brief history of the driver’s wife and son.

“Are you going to have another one?”

“Wife?”

“No, son.”

“Yes, I hope so.”

“Do you have a name yet?”

“Not yet.”

When we drifted into silence, the driver said brightly, “My name is very short.”

“That’s important,” I said. “Names have to work in a crisis. What is it?”

“Haseeb.”

“Spelled H-a-s-i-b?”

“No, H-a-s-e-e-b.”

“So not that short, then.”

At which my beautiful son finally turned, shooting me a look that meant STOP.

4

In the time which passed between the discovery of the Higgs in July 2012 and my arrival in New York in April 2014, I came to know Silvia through her letters, which she always typed on a typewriter. Through whatever she chose to tell me, piece by piece. There could be no rushing ahead, and sometimes I grew impatient waiting for a response to arrive, but there was never a time when I asked her a question and she didn’t give a direct answer.

I had considered trying to find and contact her before she found me. There had been projects at school — some of which I knew better than to bring home, and others that I thought might be harmless enough — which required grandparents. A teacher once encouraged us to ask our grandparents for recipes to put in a class cookbook that was supposed to show how life had changed between rationing and microwaves. I suggested Silvia. It did not go down well, and Susy, in her rambling explanation for why I could not, went as far as to claim that her mother-in-law had passed away.

The discovery of the Higgs boson opened up more questions than it answered. The implications, plus the letter from not-dead Silvia, meant I became even more concerned about my place in the universe. I’d wanted to study physics at university, but Susy had barred me from continuing past school, so I’d opted for a degree in philosophy instead. As far as the physics went, the space I inhabited was either the centre of some cosmic attention or one self-important speck in an infinite multitude, a bubble in an ocean of foam. Either there were physical laws, which governed every single thing that happened to me and thus connected me to everything else subject to those same laws, or everything I thought and did and everything that happened to me was essentially a mistake, in which case what was the point of physics? I consumed all the news reports when I was supposed to be revising for my finals. Some people claimed that the finding meant our universe could be doomed to fall apart.

Philosophy works best when you come up with a highly improbable, impossible, or imaginary scenario to test something — you work out what something is by what you can deduce that it is not. Creating little fantasy scenarios is what I liked about it.

I enjoyed Descartes’s demon, Locke’s soul swaps, the neo-Lockeans, and especially quantum theory, which said that an exact replica of you could suddenly appear somewhere — next door, or in another country, or even on another planet. That replica would be identical to you: same memories even, but the unity wouldn’t last long. Different environments would estrange you; for example, your replica’s parents might emigrate.

When I wrote back to Silvia, I kept it secret. Partly because it felt good to have a secret and partly because I tended to avoid doing or saying anything that might cause a disturbance in the house. I liked it when things were quiet.

To answer her first letter’s provocation, Silvia told me that she did not have email or a cell phone. She would sooner die