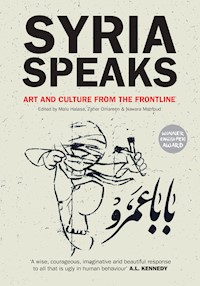

Syria Speaks E-Book

14,39 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Saqi Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

In Syria, culture has become the critical line of defence against tyranny. Villagers have joined the cultural frontline alongside urban intellectuals, artists, writers and filmmakers and to create art and literature that challenge official narratives. With contributions by over fifty artists and writers, both established and emerging, Syria Speaks explores the explosion of creativity and free expression by the Syrian people. They have become their own publishers on the Internet and formed anonymous artists collectives which are actively working in their country's war zones. The art and writing featured in this book, including literature, poems and songs as well as cartoons, political posters and photographs, document and interpret the momentous changes that have shifted the frame of reality so drastically in Syria.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

SYRIA SPEAKS

ART AND CULTURE FROM THE FRONTLINE

Edited by Malu Halasa, Zaher Omareen and Nawara Mahfoud

SAQI

Contents

Introduction

During the commissioning and editing process for Syria Speaks: Art and Culture from the Frontline, we kept asking ourselves about the value of art and culture when such untold bloodshed was taking place in Syria. Wouldn’t the voices in the anthology’s fiction, poems, critical essays, cartoons, digital illustrations, art installations, paintings, photographs and films suffer the same fate as Syria itself, and be obscured or blotted out as the sound of weapons reached a deafening crescendo?

These questions and many others seemed unanswerable at that time, but they were integral to our early motivations in putting together this book. In the end, it was the over fifty contributors to Syria Speaks – an impressive array of established and new writers, critics and artists from a cross-section of society – who provide an answer. Simply put, creativity is not only a way of surviving the violence, but of challenging it.

After three long years, many friends and people in the field have fallen into deep depressions and disappointment. Of course, none of them support the regime anymore; but they have lost their ability to back the revolution because it has become so complicated. Those who participated in it have changed, as have its political perspectives. Since the beginning of the uprising in 2011, everything has been radically altered on the ground – except for its artistic identity.

Many Syrians had thought their ‘Arab Spring’ would be different from those in Egypt and Tunisia, and they began constructing a Syrian revolutionary identity through political posters, performances, songs, theatre and videos. Even ordinary people with no experience of the arts started discovering their artistic natures in a country where free expression was often controlled and government regulated. While there are people who do not consider arts activism as an expression of popular culture, for Syrians it was a radical departure from a forty-year-long history of silence. They observed or participated in an outpouring of free expression that even surprised them, and also shocked the country’s custodians of official culture.

The artists, writers, performers and musicians featured in Syria Speaks eschew phrases like ‘conflict’ and ‘civil war’ to describe the situation in their country. For them, these words suggest an equal playing field between the aggressor – the regime of Bashar al-Assad – and the victims, the Syrian people who have been targeted by government violence and brutal sectarianism.

Despite these changes, those who participated creatively in the first year of the revolution continue their efforts; but instead of one enemy, they now face many. They believe that art is a tool of resistance, and that it is integral to social justice – emblematic of a life that is shared, not destroyed – and that it will protect Syria from the forces of Assad and the extremists in the future.

Syria Speaks opens with a veiled photomontage of the victims of the 1982 Hama uprising. This massacre took place within living memory of the majority of Syrian artists, writers and activists. However, the regime had forced the Syrian people to forget it. After the first phase of the country’s essentially nonviolent revolution in 2011 was met by extreme violence on the part of the regime, Syrian activists and artists started revisiting the events of 1982. The artist Khalil Younes explained: ‘Now when we see what happens to peaceful protestors, we suddenly realise what happened in Hama. Those people lost brothers, sisters, whole lives and nobody did anything about it. The regime has been lying to us for thirty years and those people have been living with their fear and pain for thirty years. When I came to that realisation it was terrible.’

Violence – past and present – cast a long shadow over the country. What started as a peaceful revolution was fully militarised by the summer of 2012, and many of the book’s contributors have been enmeshed in the conflict. Samar Yazbek, writing a diary of the revolution, travels through northern Syria where the rebel groups have been holding off the regime and uncovers miraculously peaceful scenes of rural life. The artist Sulafa Hijazi explains how dangerous it was to create her digital illustrations in Damascus, each one an unconscious response to the growing darkness enveloping her family and friends as they were each arrested by the regime. The filmmaker Ossama Mohammed contributes a short story, told in cinematic bursts, about a character named after Suad Hosni, the famous Egyptian film star. Suad has been going on government-sponsored demonstration marches since primary school, and is a staunch supporter of the regime until she witnesses her best friend murdered – on television – during one of the protests. ‘Lettuce Fields’, excerpted from the most recent novel by veteran author and screenwriter Khaled Khalifa, deals with approved and unapproved memories, meanings that are never allowed to be spoken of in a totalitarian state. Khalifa describes how living through this labyrinth of lies and fears unhinges a family in Aleppo. His Faulkneresque switching of tenses in fiction, a style some critics have called ‘Arabesque’, indicates where many Syrians find themselves today. This ongoing past of brutality and disinformation bloodies the present.

During this trying period, there is an understandable tendency to search for the deeper trends that have led to a society-wide breakdown. The Syrian researcher and thinker Hassan Abbas has contributed the critical essay ‘Between the Cultures of Sectarianism and Citizenship’, which examines the battle lines that have been drawn in the country today. One example of Abbas’s inclusive definition of citizenship appears in the form of new banners and signage created in Syria’s sixth-largest city, Deir al-Zour, by Kartoneh – a collective of activists who are exploring a new language of inclusiveness. Another Syrian collective, Alshaab alsori aref tarekh (The Syrian People Know Their Way), has been producing political posters and making them available online for activists to download, print and carry during demonstrations. As cited in art historian Charlotte Bank’s essay, their imagery follows a long aesthetic tradition of political posters from the Soviet Union to the Lebanese civil war. As opposed to the essentially monolithic propaganda of the regime, this anonymous group has spearheaded a growing movement of multidimensional revolutionary symbolism that has encouraged dialogue, debate, free expression and contestation. The meanings behind the representation employed by both the regime and the uprising are examined in co-editor Zaher Omareen’s essay, ‘The Symbol and Counter-Symbols in Syria’. All across Syria, cities and small towns have been developing their own visual vocabulary of resistance – none more so than the tiny hamlet of Kafranbel, where the witty cartoons photographed for this book by Mezar Matar come from. These works, often humorous yet always serious in intent, illustrate Kafranbel’s take on events and the failure of the international community to respond.

Another defining factor of the Syrian uprising has been the army of citizen-journalists who have posted over 300,000 videos, films and other visual material on the Internet, depicting what has been taking place in their country. They would not have been so well equipped or organised if not for the Local Coordinating Committees (LCC s), a network of clandestine activist cells and groups operating across the country. For the first time, Assaad al-Achi, who was responsible for obtaining spycams, laptops and software from abroad and smuggling them into Syria, reveals the shopping list of citizen-journalists operating from inside. This interview is accompanied by Omar Alassad’s survey article on the country’s alternative media scene, which has spawned local newspapers, new radio stations and even clandestine television stations, despite the violence. Another powerful example of this alternative media perspective has been the local documentary and global artistic aesthetics of the Lens Young anonymous photographers’ collective and its associated groups across Syria.

Literature has been a crucial aspect of revolutionary cultural production, and the novelist and critic Robin Yassin-Kassab sets the scene for coverage of literature in Syria Speaks, interspersed with the visual-culture contributions. The writer Ali Safar offers a melancholic diary piece about his present-day life in Damascus, while Dara Abdullah and Fadia Lazkani begin the section on prison literature and memoir. Abdullah’s ‘Loneliness Pampers Its Victims’ is a disturbing, gritty realist look at the inside of a communal cell in al-Khatib prison branch in Damascus. Lazkani’s ‘Have You Heard the Testimonies of the Photographs, about the Killings in Syria?’ is a remarkable text that took seven years to finish, and tells of the disappearance of one of her brothers in prison, and her Kafkaesque journey to discover his fate.

Well before the 2011 uprising, a history of dissent existed in Syria. Throughout the forty-year Assad dictatorship, the many prisons belonging to the country’s various security services have been filled by people who dared to confront the regime. Syria-watcher, writer and literary critic miriam cooke explains to Daniel Gorman in the latter’s essay ‘From the Outside Looking In’: ‘The domination of the cell over the Syrian imagination was huge. People in daily life would talk about their houses as cells.’ For the journalist Yara Badr, incarceration was generational; working for the Syrian Center for Media and Freedom of Expression (SCM), she was jailed as was her father before her (a political dissident from a previous decade). Her husband Mazen Darwish is SCM’s director and was instrumental in talking to the international and regional press about the events in Syria. Now he, too, is imprisoned; Syria Speaks features a moving excerpt from his letter of acceptance for the 2013 Bruno Kreisky Prize for Services to Human Rights, smuggled out of Damascus Central Prison.

For the tens of thousands of people presently incarcerated in Syria, the grave is never far away, as expressed poignantly by the artist Khaled Barakeh in an essay about his art installation, ‘Regarding the Pain of Others’ (the title is taken from Susan Sontag). In his piece, Barakeh charts the journey of a na’ash – a coffin used to carry bodies for burial – from a cemetery in Da’al in south-western Syria, to Frankfurt, Germany, where the artist presently resides. This piece includes spoken-word poems by a Free Syrian Army fighter who helped to smuggle the na’ash through the war-torn Syrian countryside into Jordan and finally to Europe, where the coffin’s dismantled pieces have been reformed into a remarkable artwork about transformation and aspiration.

With many activists, artists and writers now residing outside the country, the view of events in Syria from abroad provides another prism of pain through which to see the violence, as evidenced in Rasha Omran’s poem ‘I’m Positively Sure about the Event’. The power of culture and the role of the intellectual during the uprising are discussed by the Syrian political analyst and writer Yassin al-Haj Saleh, a recipient of a 2012 Prince Claus Award and a well-known critic in the Arab world and beyond. Saleh, once jailed for sixteen years under Hafez al-Assad, answers questions posed by Syria Speaks from his then-hiding place inside the country.

His essay is framed on either side by cartoons, a mode of cultural expression that has long revealed the hidden in Syrian society. The country’s popular editorial cartoonist, Ali Ferzat, contributes two cartoons to the book. For the young illustrators and scriptwriters from the anonymous collective Comic4 Syria, reading manga on the Internet helped them hone their storytelling skills. Their comic strip Cocktail explores a mosaic of interlacing friendships between Alawi and Sunni childhood buddies. The artist Khalil Younes addresses the same theme in ‘Chicken Liver’, his fictionalised account of a series of intertwined memories and telephone conversations he has every few days with his best friend Hassan, who has been conscripted into the army and who is serving on the dangerous frontline of Aleppo. Younes is better known for his work-in-progress pen and ink series Revolution 2011, which features the major figures of the revolution and is reproduced here.

Much of the visual material in Syria Speaks emerged from the eight-month-long touring exhibition that this anthology’s co-editors, with Donatella Della Ratta, curated on the art of the Syrian uprising. Thirty-five thousand visitors saw Syria’s Art of Resistance, in conjunction with CKU, the Danish Centre for Culture and Development, at the Rundetårn in Copenhagen during the 2013 Easter Week. For that show, the artist Mohamad Omran and the poet Golan Haji produced a new illustration and poem every day for the first four days of the exhibition. Their collaboration, Daily Occurrences (two of which are reproduced in this book), draws very specifically on the immediate situation in Syria during that period, and addresses issues of belonging and exile. An earlier version of the exhibition, then entitled Culture in Defiance: Continuing Traditions of Satire, Art and the Struggle for Freedom in Syria, was first shown in Amsterdam at the Prince Claus Fund Gallery in 2012, and also came to London’s Rich Mix’s Gallery Café in Shoreditch as part of the 2013 Shubbak: Window on Contemporary Arab Culture Festival.

Throughout the uprising, music and song have been essential expressions of Syria’s ‘Revolution of Dignity and Freedom’. The chanters and singers inspired the thousands at mass demonstrations that took place all over the country in 2011; they continue to sing and perform today, although the crowds are smaller and gather more secretively. These musicians have their roots in the arada, a traditional performance that usually takes place during weddings. The lyrics of the revolution’s best-known song, ‘Come on Bashar, Get Out!’, by Hama’s tragically murdered singer Ibrahim Qashoush, are published alongside the words of another song, ‘Female Refugees’, by Monma, Al-Raas and Al Sayyed Darwish (all pseudonyms). In an accompanying interview, rapper Darwish admits that he was initially against the revolution until ‘the street’ convinced him to change sides.

Since 2011, Syrians have been forming anonymous artistic collectives – a trend that was not encouraged before the revolution, as civil society initiatives were regularly quashed by the regime. In response to anonymity on both collective and personal levels, Syrian artist Youssef Abdelke insisted that the painters, illustrators, graphic designers and sculptors, among many others, sign their real names to the wide range of artistic production featured on the Facebook page ‘Art and Freedom’. This was, for some, a great personal risk, and Syria Speaks features a wide range of artistic production by artists Yasmeen Fanari, Waseem al-Marzouki, Khaled Abdelwahed, Akram al-Halabi, Nasser Hussein, Randa Maddah, Rima Bedawi, Samara Sallam, Amjad Wardeh and Wissam al-Jazairy. When Abdelke was arrested in July 2013 at a regime checkpoint and held for more than two months before being suddenly released, a very personal five-year photographic project about his relationship with his charcoal paintings came to light and was published for the first time by the artist’s friend, the photographer Nassouh Zaghlouleh.

Film is the one medium that has crossed the boundaries of art, documentary, politics and consciousness-raising. The two series of puppet plays TopGoon: Diaries of a Little Dictator by the anonymous collective Masasit Mati showed early on that Syrians were producing powerful moving-image responses to the revolution. The collective based its five-minute short videos on finger puppets, as these were easy to smuggle through checkpoints. Many of the films, now posted on YouTube, Facebook and Vimeo, are morality tales filled with the blackest of humour. They also act as a barometer for the changing trends of the Syrian uprising. One, called The Monster, ends with Nietzsche’s famous caveat: ‘Be careful when you fight the monsters, lest you become one.’

Of all the Arab uprisings, the Syrian revolution has been the most YouTubed. The art historian Chad Elias, with Zaher Omareen, examines the filmic tropes that have been posted and what they reveal about the art of cinema and information-gathering. The final short stories in the anthology – ‘A Plate of Salmon is Not Completely Cleansed of Blood’ by Rasha Abbas and ‘The Smartest Guy on Facebook’ by Aboud Saeed – are fast fiction at its best. Abbas’s story takes place in an apartment stalked by a sniper, while Saeed represents the rise of new, working-class storytellers from Syria; Saeed himself was a metalworker who left school in the ninth grade before finding his voice on the Internet and writing about his town of Manbij and his traditional, henna-tattooed mother.

For a revolution that began in Deraa with graffiti, it is only fitting to end Syria Speaks with stencils from Freedom Graffiti Week Syria, showing the faces of fallen martyrs that have been spray-painted by activists and artists all over the country. Although some people might find the very idea morbid, within the context of a people’s revolution they represent the triumph of street art; they are also a timely reminder of the originality of this art form when it first appeared on the streets of New York in the late 1970s. It has now regained its radicalism and power on the streets of Deraa and Homs.

If there is a single message in Syria Speaks, it is that meeting violence with violence is never successful. The artistic response to the Syrian uprising is far more than a litany of turmoil; it illustrates the accelerated experiences of a people, many of whom have been fighting for their survival. It shows their innate ability to overcome, and their dreams for the future of their country. For Syrians and non-Syrians alike, there are many reasons to wake up every morning and reach for the pen, the easel, the camcorder or the laptop – instead of a gun.

Malu Halasa and Zaher Omareen London, March 2014

Anonymous 82, 2013 21 x 15 cm Photography and digital illustration

Hama ’82

Before 2011, public discussion of the Hama massacre was forbidden. Whenever Syrians wanted to refer to it, they used the euphemism ahdath 82 (‘the events of [19]82’). A year into the revolution, for their Facebook campaigns, activists began collecting unpublished eyewitness accounts, information, stories and photographs related to the massacre – including these portraits of victims taken from identification cards and official family booklets.

The number of people killed when government troops controlled by Bashar al-Assad’s father Hafez attacked the city during February 1982 has been estimated at between 10,000 and 25,000. Thousands more were detained, and Hama was almost completely destroyed. Actual data about the attack have been effectively suppressed by the regime. While some of the victims have been identified, many others have not.

Samar Yazbek

GATEWAYS TO A SCORCHED LAND

A road journey through the conflict

‘We found him six days later, abandoned in the forest. He disappeared on 24 March 2012, the day the army invaded Saraqeb.

‘His body hadn’t been discarded carelessly; it was wrapped into a bundle. There was a terrible smell in the air, but no clear bloodstains. It was the deep wound on his throat that was obvious. He had been slaughtered like an animal, it seemed. His clothes were in place, coated in a layer of dust. From a distance his body looked like a piece of fabric abandoned randomly, but this cloth carried the body of a young man from the Aboud family, the first to be martyred on the day of the invasion. We thought he had been arrested like so many others, but in fact he had been killed. In our hearts the young man had lived another six days. Perhaps that was enough. I am certain that the boy was attacked unjustifiably; he had left his gun at home that day, gone out and vanished. Had he been armed, he would not have surrendered so easily – but they double-crossed him. The wound on his throat had been made from behind, and our martyr happened to be wearing new clothes when his blood began to soak into the dust.

‘After the first invasion, on the Saturday, the army retreated. This was a tactic; a small military presence remained and, the following Tuesday, they returned to attack the towns of Taftanaz and Jarjanaz, and to force the entire region of Idlib to surrender once more. In Jarjanaz they torched seventy houses, in Saraqeb a hundred. The tanks came in and soldiers invaded the houses in great swathes. By the time they had left, Saraqeb was a heap of rubble. We lost the best of our young men that day. Sa’ad Bareesh had been injured earlier when shrapnel became lodged in his hand and leg. He had been at his sister’s house when they raided it and tore it to pieces. They took his sister’s son, Idi al-Omar, from her arms and dragged them both into the street. Sa’ad was screaming, but they paid no attention. The soldiers pulled them through the streets until they were out of sight. The sister started to scream, following them down the street. They threw her to the ground and vanished. That’s when we heard gunfire. She started running again, then fell to her knees and continued to crawl toward where the shots were coming from.

‘We found the two young men – her brother and son – dumped on the ground beside a wall. They had been shot in the head, and all over their bodies. Even in the wounds on the brother’s leg and hand, a bullet had ruptured the flesh. A short while later the very same woman allowed another group of soldiers into her home, who had come looking for her second son. The soldiers were hungry, so she cooked them something to eat. When one of them started to shout abuse, she cursed him in return and said: “You are in my home, eating my food, and you dare to shout at me?” The soldier fell silent, and instructed his companions not to harm the woman; yet they still seized her teenage son when they left. The soldier who had shouted at the woman seemed pained by her tears as she begged them to hand back her son, yet he remained silent. Her son would be returned to her dead, and this soldier seemed to know not only that they would kill him, but that he was the second of her sons to be killed.

‘Nevertheless, the young men did not surrender. They did not cower before the army’s great numbers, the continued bombardment and the constant slaughter; they stayed to protect their homes until they were out of ammunition. Six of the fighters remained and found themselves surrounded, without ammunition. The army invaded the well-fortified house and set fire to the basement. They were about to kill the owner of the house, an elderly man, when his wife knelt at their feet and pleaded: “I beg you, my sons, don’t kill him. I am on my knees, please let him go. He’s just an old man; he’s got nothing to do with this.” They didn’t kill the man, but they did beat him severely before throwing him into the street. The soldiers took the six men, aged between twenty and thirty, and forced them to stand against a wall. Then they opened fire. In the space of a few minutes, all had fallen to the ground, their bodies spread across it in an overlapping sprawl. In silence, the soldiers departed.

‘The next day, the soldiers patrolled the streets. They stopped Muhammad Aboud in the middle of the road and opened fire on him. Then they seized his brother. This was the same day they killed Muhammad Bareesh, known by the nickname “Muhammad Haaf”.1 The soldiers hadn’t had the courage to confront him head-on; Muhammad was well-known for his strength and fearlessness, as the leader of a very popular faction in Saraqeb. From an aircraft hovering above, soldiers launched a machine-gun assault against him. Meanwhile, on the ground, a heavy infantry combat vehicle supported the aircraft, spraying bullets in every direction. After they killed him and made certain that he was dead, the soldiers drew closer, dancing and shouting for joy.

‘Zaheer Aboud, who was captured that day, was released after three months of torture. A few days after his release, he was shot by a sniper while walking through Saraqeb.’

The army had secured a temporary victory. ‘We were shooting Kalashnikovs and they were fighting back with tanks and planes. But, as I say, the victory is only temporary; they have won the battle, but not the war …’

This was the end of the young rebel leader’s account of the first invasion of Saraqeb.

The sun was blazing down, so intense that it was impossible to cry. Everyone spoke with granite-like solemnity; a brief sigh was enough to occupy the whole space. We were driving in two cars across the northern countryside to Aleppo, Idlib and Hama. Over the course of our journey, we stopped at several checkpoints and bases belonging to armed groups. It was as though we had uncovered Syria’s true identity after all this time: a country made of earth, blood and fire, where explosions never ceased. There was dust everywhere, and flames still flickered in the distance. The villages were eerily silent, like ghost towns. We saw only a few people, and the sound of circling aircraft filled the air. The shelling had happened at some distance from where we were. ‘It might not seem like it now, but a rocket could fall on us at any moment,’ the young man said.

I was on the verge of crying. The deserted road, the silent villages, passing through the armed checkpoints in the midday sun, the dust in my eyes; it was almost enough to bring me to tears. But then I noticed something moving. At the other end of a wide field, jets of water were spraying the crops. Life was still going on, despite everything else! On the horizon, a girl no older than fifteen came into view. My heart pounded as I looked toward the sky. Could she be the target of an airborne sniper? The girl was playing in the sprinklers, dousing her head with water. She took off her headscarf and dampened it too, using it to wipe her face. A collection of domed mud houses appeared and a small truck passed us by. In the back of the truck a group of young veiled girls stood squeezed together, each carrying a hoe. A small number of older women stood next to them. The truck stopped and the girls got off, heading for the field. This place couldn’t possibly become the jihadis’ pasture when the agricultural lifestyle made it necessary for women to work in the place of men.

Tired villages bathed in sun and poverty. Every name had a peculiar ring to it, and a surprising meaning: Riyaan, Louf, M’israni, Qatra, Kaff Amim, Qatma.2 Other villages, too, fought a two-pronged battle against the threat of death by poverty and the chance that death might fall directly from above instead. The women and girls climbed down from the wagon and headed in the direction of the field. Their veils left only their eyes uncovered, protecting their faces completely from the midday sun. These women did the same work as men, yet still faced oppression in various forms.

In the distance we spotted what looked like a small hill. It was the ancient kingdom of Ebla, in the village of Tell Mardikh, where civilisation has flourished since the third millennium BC. A young man in the village told us several rockets had fallen, but that there had been no casualties. Luckily for the ancient ruins, the missiles had landed on the outskirts.

The sun glared down and all signs of life vanished once more, except for the few small flocks of birds that traversed the silence. We needed to visit several groups belonging to the resistance battalions; the young men needed provisions, and there was the problem of an abduction that they hoped the leader of one of the tribes would help them to resolve. At midday we arrived at the base belonging to the Liberators of the Tribes Brigade. There were two groups of us in two separate cars. The men began negotiations to buy a host of weapons, as they no longer had enough artillery to defend themselves. I was left to watch. The bullets glistened in the sunlight as the men tossed them between their hands, scattering them like lentil seeds. There wasn’t a huge amount, barely enough to defend those few houses. But it would have to suffice for the rebels to regain possession, and all the better if a deal could be struck at a lower price, as they hadn’t the money to pay in full.

Grimacing in the sunlight, we entered a building where four young men were expecting us. Their weapons amounted to no more than Kalashnikovs and their base had no landline or Internet connection. There weren’t many mobile telephones either; reception had been cut off across the region. The fighters occupied just two rooms with a small collection of rudimentary firearms. They were fighting against tanks and planes, and yet had proven themselves capable of defeating heavily armed battalions on the ground, forcing them to retreat. Meanwhile the sky was a great Grim Reaper, haunting from above.

A UNITED SYRIA WHERE THE ONLY SECT IS FREEDOM

The young man sitting beside the group’s leader apologised for the state of the place. There was a table and several chairs, and the room was filled with harsh sunlight. The soldiers’ faces had tanned a dark brown. On my next visit, I would find that the base had been successfully targeted. But this time, before the raid, we were in a hurry to get to the Ammar al-Muwali tribe, to meet with one of its leaders. There I would discover for myself their poverty, dignity and courage. I would hear many stories, the last of which concerned ways to protect the grain stores from being pillaged so that the people would not starve. We discussed, with a group of young men together with the leader of the tribe, the importance of establishing a civil state and a united Syria where the only sectarian belief is freedom. Towards the end of the meeting I witnessed the men discuss how to resolve the matter of the abduction. The details of this meeting would have to be examined thoroughly in order for me and many other educated Syrians like me to understand the meanings of tolerance, altruism and dialogue – three simple words that capture everything the young men said, and which merit my repeating the particulars in full one day.

Despite the unusual discoveries we made in those remote country villages, the words of one soldier would not leave my mind. He was a defector from the army, whom I met at that same base. When we stopped the car, away from the sight of weapons, his story was still there, ingrained in my mind, along with the glint I thought I had noticed in his dull gaze.

‘He was my friend … We grew up together. The last two years, we’d been together the whole time. He was always at my side. We were in Homs, wrecking this neighbourhood. They’d told us there had been armed terrorist attacks. We went into this house and destroyed everything in it and an officer started yelling at us and swearing. He wanted one of us to rape this girl. The family was hiding in one of the rooms, and the officer ordered us to prepare ourselves. He scrutinised each of our faces in turn, and then he stopped and hit Muhammad hard on the back. He was ordered to enter the room. My friend was from the coast too, from a village close to where the officer was from, in al-Ghab. Muhammad was terrified and backed away, so the officer started insulting him and calling him a “woman”.

THE SKY WAS A GREAT GRIM REAPER, HAUNTING FROM ABOVE

‘Muhammad crouched on the ground, bent down to the officer’s feet, then started kissing his boots and pleading with him. He cried: “Please, Sir, please, by God, I can’t do it. Please don’t make me.” The officer kicked him once, then started really going for it. He grabbed him by the crotch and said: “I’m going to cut this off, you woman!” My friend started to cry – you should have known Muhammad, he never cried, he was a really brave guy. But I saw him cry like a child, at the top of his voice. His mouth was covered in snot and saliva and he was begging the officer not to make him go through with it. He was my friend; we’d shared all sorts of secrets. I knew he had a girlfriend; he was a good-looking guy.

‘The officer put his hand on Muhammad’s crotch and said: “You want me to teach you how to do it, hey, woman? You want me to show you how?” Then Muhammad kicked him and pounced on him. He was a strong guy, strong enough to floor the officer. Muhammad started beating him, then stopped and threw down his gun. The officer got up off the ground immediately and opened fire at Muhammad. He killed him.

‘I saw all of this with my own eyes. You know which part of Muhammad’s body he chose to fire at?’ The young man fell silent for a few moments then indicated his crotch, without any sign of embarrassment. ‘Here. And when the officer ordered our other friend to go in and rape the girl, the guy went in without saying a word. We heard her scream. We heard her mother scream and her brothers and sister scream, because they were all crowded together in another room. Their father was a defector. He’d been killed two days before. This was in Rif Homs, and in some parts of Homs itself. That was the day I decided to defect.’

The youth stood still, holding his gun. ‘But I’m telling you, not a day goes by without me seeing Muhammad in my sleep. I’ve got his letters to the girl he was in love with. I’m keeping them safe. If I’m still alive, I’ll get the letters to her. On Muhammad’s precious soul, I’ll get them to her, even if they slaughter me.

‘… If I’m still alive,’ the young man echoed. In the gruelling midday sun, the distant thunder of missiles echoed too.

Translated from the Arabic by Emily Danby

1 He used Haaf (‘plain’ or ’simple’) in place of his surname, in order to keep his identity secret.

2Riyaan means ‘well-watered’; louf, ‘loofah’ or ‘dried gourd’; m’israni, someone who works a press (e.g. oil); qatra, ‘droplet’; kaff amim, ‘the common hand’; and qatma, ‘little morsel’.

The digital art and illustration of Sulafa Hijazi

Ongoing

An artist reveals her motivation

Birth, 2012 70 x 85 cm Digital print

I grew up in a militarised society. We wore army uniforms to school, where we learned to fire weapons under the pretext of facing ‘the enemy’ in the future. The Syrian regime harnessed the Syrian people since early childhood, placing them in the service of the military machine. They became one of the tools of the regime’s oppression.

I try to reflect this idea in one of my illustrations in the series Ongoing. It depicts a sewing machine making use of a human being for thread. Another shows children riding on the backs of soldiers; it is their way of avenging their stolen childhood. They also attempt to eat the tools of repression and weapons of war.

Untitled, 2012 80 x 100 cm Digital print

The artwork also explores the cycle of violence in Syrian society. The repressive violence of the state has, in turn, generated a violent reaction against it. People have been exposed to brute force in schools, on buses, in the streets, in jails and during demonstrations, so their normal response is aggression. The violence takes a variety of forms: religious radicalisation, gangs … and the civil war.

This cycle of violence serves the purposes of the regime, providing it with a pretext to murder people. It keeps the authorities in power and effectively destroys society. It works like the wheel in one of my illustrations, where soldiers shoot at each other. The concept of cyclical violence is one of many I was exploring, unconsciously, while living in Syria during the revolution.

Untitled, 2013 80 x 60 cm Digital print

Untitled, 2012 60 x 60 cm Digital print

Before I left the country in 2012, people were still trying to do something positive. We had great hopes about the prospect of changing our country through peaceful means. There was still a space in our society for us to do this. Then it started to become violent; the regime began arresting activists (including members of my family, and friends) and kicking them out of Syria or making conditions so unbearable for them that they had to flee. There are still many courageous people working inside the country, but their numbers are becoming fewer and the sound of weapons drowns out the voices of peaceful activism.

In Ongoing, I am intrigued by life and death: suddenly, death in Syria became a fact of life. It became normal, very common among people who lost relatives. Death was something we came to take for granted; we got used to dealing with the high murder rate simply as numbers. I tried to reflect the contrast between life and death in the illustration of a pregnant weapon.

I also pondered the implications of masculinity in killing, power, dictatorship and domination. I believe that if women were in charge of the world, there would be no more war. Women who give birth know the meaning of life. Some of the illustrations – the man giving birth to a weapon or the man masturbating – communicate this idea.

Untitled, 2012 100 x 60 cm Digital print

Masturbation, 2011 60 x 80 cm Digital print

I experienced contradictory feelings during the revolution – a mixture of fear, courage, hope, pain, guilt, weakness and alienation. Over the past two years, when I stayed in Syria, drawing was the only tool I could use to share all these feelings with people inside and outside the country, through online social networks. The image of the man trying to keep himself away from a massacre is a reflection of this time; he has just realised what has happened, and is full of hopelessness and pain.

I purposely did not include pictures of the President or any elements related specifically to Syria in the series. I wanted this artwork to be about any conflict situation with accompanying humanitarian issues. However, these illustrations were born out of my experiences in Syria, and I represent an aspect of my identity in the illustrations: the pale colours I experienced in my city. Those dull colours come from the socialist regime of our youth.

For my films, which are mostly animated, we work on concepts of character design, i.e. the visual representation of character development. For Ongoing, I used animation software and a digitiser. Creating these illustrations in Syria was not easy. I knew that at any time, the authorities could come to my house and demand to see what I was working on. However, it is safer doing digital art – you can hide the files on your computer and scrap them easily if necessary.

When I left my country, I had what can only be described as ‘disconnected memory’. After two intense years of such conflict, you feel you need space and time out to rebuild yourself. After being away for about five months, I have started to think about the situation and relive it again. I’ve had a tough time trying to draw. Inside Syria, people live as prisoners inside a huge cell. Once we try to escape from there, we discover that we are still inside.

Untitled, 2012 60 x 60 cm Digital print

Ossama Mohammed

The Thieves’ Market

I was born, grew up, came of age, fell in love, abandoned someone and was abandoned, all on a demonstration that ended yesterday.

My name’s Suad. I didn’t use to like it, on account of my Aunt Suad – I didn’t want to be like her. But after Suad Hosny, I became reconciled with my name: I saw her 1972 film Watch Out for Zouzou and I cheered up, because as the song says: ‘Life turns rosy when you’re beside me and I’m beside you …’

Shyness makes me shy.

I’ll tell you my story and you can write it down.

I trust you.

Yesterday my soul changed course.

Yesterday, after I came home from the million-strong march.

Honestly, I swear to God, there were a million of us.

One million is the number of steps I’ve taken since my childhood, in march after march.

I grew up, came of age, abandoned someone and was abandoned, on a march that finished yesterday.

Primary School

In the first year of primary school, the teacher walked in one day and said: ‘No absences tomorrow.’ He ordered us to have breakfast before coming to school, and not to bring our schoolbags with us. ‘No classes tomorrow,’ he said, and the children shouted: ‘Yeeaaaahhhh!’

‘Tomorrow there’s a demonstration.’

I don’t know why I was happy to hear that – I am clever …

So that’s how I started walking. I walked all the way home. I woke up next day and put on my beautiful clean clothes, and tied my hair up in a white ribbon. I kissed my mother and said: ‘I’m going to school, Mum’, then I kissed my father and said: ‘I’m going to school, Dad’, and I left the house.

However, I forgot the teacher’s instructions, and brought my schoolbag with me. I swung it to and fro as I walked, memorising my reading lesson. I forgot a word and suddenly noticed the bag: I stopped as if to turn back, but was afraid I’d be late, so I took it along with me to the march. Imagine – the whole school without their books, and just me carrying my bag!

We got on the bus and sat down. I opened my book and began reciting my reading lesson under my breath: ‘Oh river, do not flow away, wait for me to follow you.’

‘Ha ha – you parrot!’ Khadija said as she sat down next to me. ‘You just repeat it!’

The rest of the children came crowding into the bus, a jostling jumble of male and female, from all the different school years – five-year-olds, eight-year-olds, ten-year-olds.

The teacher shouted: ‘Syria, Syria, who created you?’ and suddenly something shot out of his mouth. It rolled under the seat in front of me – I could see it between my feet, spinning like the dice in a backgammon game. Three false teeth. The teeth were dirty. The teacher spat on them, rubbed at them a bit with his fingers, and put them back in his mouth. ‘Yuck!’ – I closed my eyes to shut out the disgusting sight.

I got down from the bus with my eyes closed, and chanted with my eyes closed. Then I opened them: I was short, and I saw the sky and the slogans and the pictures of the President on top of the buildings. Khadija was chanting up to the clouds above the teacher. A flock of pigeons flew by. With his hand over his mouth the teacher chanted: ‘Syria, Syria, who created you?’

I shouted: ‘The Socialist Ba’ath Party!’ while still saying: ‘Oh river, do not flow away’ to myself at the same time.

Some time after that, we made compulsory donations to something called ‘the war effort’, and I heard that the teacher had siphoned off part of the total raised to buy himself some new teeth.

Secondary School

One day during the first year of secondary school, the head teacher came in and said: ‘Tomorrow we’re all together. No absences tomorrow.’

We walked and we chanted. We walked along al-Quwatli Street, and we walked along Hanano Street, and we all gathered in 8th March Street. I didn’t know that al-Quwatli Street was named after Shukri al-Quwatli, nor that Hanano Street was named after Ibrahim Hanano. We passed Jaara’s Ice Cream Shop and the Pyramids Cinema.

‘Yasqut, yasqut, yasqut!’ – ‘Down, down, down! Down with the enemy!’ shouted the kids. ‘Promise me everything,’ sang Khadija; it was the chorus from the Suad Hosny song about springtime. ‘Promise, promise, promise,’ we chanted together, laughing. So she started making every nationalist chant culminate in the word ‘promise’, and then we’d repeat: ‘Promise, promise, promise!’ I was giving my oath, feeling embarrassed and aware of my femininity. Khadija was so very dear to my heart.