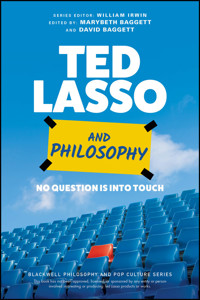

Ted Lasso and Philosophy E-Book

14,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Serie: The Blackwell Philosophy and Pop Culture Series

- Sprache: Englisch

An accessible and engaging journey through the philosophical themes and concepts of Ted Lasso

Ted Lasso and Philosophy explores the hidden depths beneath the vibrant veneer of AppleTV's breakout, award-winning sitcom. Blending philosophical sophistication with winsome appreciation of this feel-good comedy, the collection features 20 original essays canvassing the breadth of the series and carefully considering the ideas it presents, including the goal of competition, the role of mental health, sportsmanship, revenge versus justice, the importance of friendship, the imperative of respect for persons, humility, leadership, identity, character growth, courage, journalistic ethics, belief, forgiveness, what love looks like, and just how evil tea is. In a nod to the show’s many literary allusions, the compilation concludes with a whimsical appendix that catalogs the books most significant to Ted Lasso's themes and characters. If football is life, as Dani Rojas fondly repeats, then this book’s a fitting primer.

- Covers the full breadth of the original Ted Lasso series, including the third season

- Explores every major character and all of the show's significant subplots and elements

- Written in the spirit of the show, with in-jokes that will appeal to Ted Lasso fans

- Features an introduction that guides readers through the book's materials

- Includes Beard's Bookshelf, a bibliography of the most significant books shown or alluded to in the series

Ted Lasso and Philosophy is for the curious, not judgmental. Sport is quite the metaphor, and we can't wait to unpack it with you.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 467

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

Table of Contents

Cover

Table of Contents

Series Page

Title Page

Copyright Page

Dedication Page

A Taste of Athens

Part I: DO THE RIGHT‐EST THING

1 On the Pitch with Saint Augustine

What Is Love?

The

Ordo Amoris

in Ted Lasso

Worship at Crystal Palace

Saints and Scamps

Ted Lasso: The Father We Never Had

Notes

2 Isaac Finds His Flow

The

Dao

of Isaac

“Do without Ado,” McAdoo!

Barbers, Butchers, and Football Players, or “Football Is Life!”

How to Cook a Small Fish

Notes

3 Ted Talk, Precursive Faith, and the Ethics of Belief

Belief in Belief

The Ethics of Belief

Precursive Faith

Gotta Look Right

Faith and Practice

Rightness, Religion, and Relations

Notes

4 Is Ted an Egoist?

The Nature of Enlightened Egoism

Is Ted Lasso an Egoist?

Time to Face the Press

Notes

Part II: THE BEST VERSIONS OF OURSELVES

5 Fear’s a Lot Like Underwear

Like Riding a Horse

Let’s Get Started, Shall We?

They Really Should Write Songs About It

A Longer Run Than He Thinks

Onward, Forward

Notes

6 Lassoing Aristotle

A Bad Start for Rebecca, Nate, Roy, and Jamie

Immorality ➡ Loneliness ➡ Misery

Best Version of Ourselves

Princess and Dragon

You Complete Our Team

Jamie Less Tart

Self‐Love and Self‐Loathing in Richmond

A Work in Progmess

Notes

7 Ted Lasso’s Personal Dilemma Squad

Personal Metaphorical Saint Bernard

The Lasso Way

Best Versions of What?

The Knights of Support

A Team United

Notes

8 The Affable Gaffer

Seems Mighty Fragile

The Power of Friendship

Three Amigos

Hire Your Best Friend?

Friendly Bantr

The Lasso Way

Notes

Part III: MAN CITY

9 Poop in the Punchbowl

The Anatomy of BS

The Good Guys of

Ted Lasso

Portrait of a BS Artist As an Old Man

A Yardstick for Growth

Notes

10 Doing Masculinity Better

I Want to Torture Rupert

Success Is Not About the Wins and Losses

Between the Goal Posts

Missing the Mark

Time to Woman Up

Doing the Right Thing Is Never the Wrong Thing

Notes

11 Inverting the Gender Pyramid

Playing a Man Down

Perhaps Not an Oasis

Suffering Is Necessary

Be Curious, Not Judgmental

Holding On to Your Manhood

Inverting the Pyramid the Richmond Way

Notes

12 Who Is Right, Ted or Beard?

Winning Is the Only Thing

The Lasso Way

The New Lasso Way

The Answer

Notes

Part IV: MOSTLY FOOTBALL IS LIFE

13 Amplifying Emotion and Warmth at Richmond

“Strange” by Celeste

“Wise Up” by Aimee Mann

“Piano Joint” by Michael Kiwanuka

“She’s a Rainbow” by The Rolling Stones

“Roy Walk Off” by Marcus Mumford and Tom Howe

“Spiegel im Spiegel” (Arvo Pärt) by Nick and Becka Mohammed

The “

Ted Lasso

Theme” by Marcus Mumford and Tom Howe

Notes

14 Is This Indeed All a Simulation?

Could This All Be a Simulation?

Bostrom’s Simulation Questions

Bostrom’s Simulation Equation (Without the Math)

Is Led Tasso Real?

Tipping Coach Beard’s Cap

Notes

15 Kansas City Candide Meets Compassionate Camus

Rom‐Communism

Candide

Principle of Sufficient Reason

Greater Goods Theodicy

Problems with Panglossian Optimism

Can Don’t

The Plague

Affirmative Atheism

Hope Is Suicidal

A Strange Hope

One Is the Loneliest Number

Belief in the Collective

No “I” In Team

Notes

16 Ted’s Chestertonian Optimism

Inverting the Pyramid

Chesterton’s Relentless Delight

Believe in What, Exactly?

An Adequate Foundation

Notes

Part V: SMELLS LIKE POTENTIAL

17 What To Do with Tough Cookies

A Salty Bunch

Trent Crimm,

The Independent

Cover‐Up Revealed

Looking for Something Deeper

Notes

18 Stoic Bossgirl

Slacker or Stoic?

The Have‐It‐All Generation

Rebecca aka da Boss

Girlboss Mentor

Being the Boss on Bantr

Soccer Mom

Notes

19 Why a Headbutt Might Have Hurt Nate Less

Life’s Most Complicated Shape

Change Is Scary

All Apologies

Can You Make Me Famous?

Nate the Great

The Hope That Kills You

Notes

20 Is Rupert Beyond Redemption?

Maybe We’ll Turn It Around

Reverse the Curse

Being Accountable Matters

The Dark Forest

Like a JIF (Or Is It GIF?)

Every Choice Is a Chance

Notes

Beard’s Bookshelf

You Do Not Want to Judge These Books by Their Covers

Notes

Starting Lineup

Index

End User License Agreement

Guide

Cover Page

Table of Contents

Series Page

Title Page

Copyright Page

Dedication Page

A Taste of Athens

Begin Reading

Beard’s Bookshelf

Starting Lineup

Index

WILEY END USER LICENSE AGREEMENT

Pages

ii

iii

iv

v

ix

x

xi

1

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

173

174

175

176

177

178

179

180

181

182

183

184

185

186

187

188

189

190

191

192

193

194

195

196

197

198

199

201

202

203

204

205

206

207

208

209

210

211

212

213

214

215

216

217

218

219

220

221

222

223

224

225

226

227

228

229

230

231

232

233

234

235

236

237

238

239

240

241

The Blackwell Philosophy and Pop Culture SeriesSeries editor: William Irwin

A spoonful of sugar helps the medicine go down, and a healthy helping of popular culture clears the cobwebs from Kant. Philosophy has had a public relations problem for a few centuries now. This series aims to change that, showing that philosophy is relevant to your life—and not just for answering the big questions like “To be or not to be?” but for answering the little questions: “To watch or not to watch South Park?” Thinking deeply about TV, movies, and music doesn’t make you a “complete idiot.” In fact, it might make you a philosopher, someone who believes the unexamined life is not worth living and the unexamined cartoon is not worth watching.

Already published in the series:

Alien and Philosophy: I Infest, Therefore I AmEdited by Jeffery A. Ewing and Kevin S. Decker

Avatar: The Last Airbender and PhilosophyEdited by Helen De Cruz and Johan De Smedt

Batman and Philosophy: The Dark Knight of the SoulEdited by Mark D. White and Robert Arp

The Big Bang Theory and Philosophy: Rock, Paper, Scissors, Aristotle, LockeEdited by Dean A. Kowalski

BioShock and Philosophy: Irrational Game, Rational BookEdited by Luke Cuddy

Black Mirror and PhilosophyEdited by David Kyle Johnson

Black Panther and PhilosophyEdited by Edwardo Pérez and Timothy Brown

Disney and Philosophy: Truth, Trust, and a Little Bit of Pixie DustEdited by Richard B. Davis

Dune and PhilosophyEdited by Kevin S. Decker

Dungeons and Dragons and Philosophy: Read and Gain Advantage on All Wisdom ChecksEdited by Christopher Robichaud

Game of Thrones and Philosophy: Logic Cuts Deeper Than SwordsEdited by Henry Jacoby

The Good Place and Philosophy: Everything is Fine!Edited by Kimberly S. Engels

Star Wars and Philosophy Strikes BackEdited by Jason T. Eberl and Kevin S. Decker

The Ultimate Harry Potter and Philosophy: Hogwarts for MugglesEdited by Gregory Bassham

The Hobbit and Philosophy: For When You’ve Lost Your Dwarves, Your Wizard, and Your WayEdited by Gregory Bassham and Eric Bronson

Inception and Philosophy: Because It’s Never Just a DreamEdited by David Kyle Johnson

LEGO and Philosophy: Constructing Reality Brick By BrickEdited by Roy T. Cook and Sondra Bacharach

Metallica and Philosophy: A Crash Course in Brain SurgeryEdited by William Irwin

The Ultimate South Park and Philosophy: Respect My Philosophah!Edited by Robert Arp and Kevin S. Decker

The Ultimate Star Trek and Philosophy: The Search for SocratesEdited by Jason T. Eberl and Kevin S. Decker

The Ultimate Star Wars and Philosophy: You Must Unlearn What You Have LearnedEdited by Jason T. Eberl and Kevin S. Decker

Terminator and Philosophy: I’ll Be Back, Therefore I AmEdited by Richard Brown and Kevin S. Decker

Watchmen and Philosophy: A Rorschach TestEdited by Mark D. White

Westworld and Philosophy: If You Go Looking for the Truth, Get the Whole ThingEdited by James B. South and Kimberly S. Engels

Ted Lasso and PhilosophyEdited by Marybeth Baggett and David Baggett

Forthcoming

Joker and PhilosophyEdited by Massimiliano L. Cappuccio, George A. Dunn, and Jason T. Eberl

Mad Max and PhilosophyEdited by Matthew P. Meyer and David Koepsell

The Witcher and PhilosophyEdited by Matthew Brake and Kevin S. Decker

For the full list of titles in the series see www.andphilosophy.com

TED LASSO AND PHILOSOPHY

No Question Is Into Touch

Edited by

Marybeth Baggett

David Baggett

Copyright © 2024 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved.

Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey.Published simultaneously in Canada.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per‐copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750‐8400, fax (978) 750‐4470, or on the web at www.copyright.com. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, (201) 748‐6011, fax (201) 748‐6008, or online at http://www.wiley.com/go/permission.

Trademarks: Wiley and the Wiley logo are trademarks or registered trademarks of John Wiley & Sons, Inc. and/or its affiliates in the United States and other countries and may not be used without written permission. All other trademarks are the property of their respective owners. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. is not associated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book.

Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. No warranty may be created or extended by sales representatives or written sales materials. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for your situation. You should consult with a professional where appropriate. Further, readers should be aware that websites listed in this work may have changed or disappeared between when this work was written and when it is read. Neither the publisher nor authors shall be liable for any loss of profit or any other commercial damages, including but not limited to special, incidental, consequential, or other damages.

For general information on our other products and services or for technical support, please contact our Customer Care Department within the United States at (800) 762‐2974, outside the United States at (317) 572‐3993 or fax (317) 572‐4002.

Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic formats. For more information about Wiley products, visit our web site at www.wiley.com.

Library of Congress Cataloging‐in‐Publication DataNames: Baggett, David, editor. | Baggett, Marybeth, editor. | John Wiley & Sons, publisher.Title: Ted Lasso and philosophy : no question is into touch / edited by David Baggett, Marybeth Baggett.Description: Hoboken, New Jersey : Wiley‐Blackwell, [2024] | Series: The blackwell philosophy and pop culture series | Includes index.Identifiers: LCCN 2023037911 (print) | LCCN 2023037912 (ebook) | ISBN 9781119891932 (paperback) | ISBN 9781119891949 (adobe pdf) | ISBN 9781119891956 (epub)Subjects: LCSH: Ted Lasso (Television program). | Television–Philosophy.Classification: LCC PN1992.77.T38435 T43 2024 (print) | LCC PN1992.77.T38435 (ebook) | DDC 791.4501–dc23/eng/20231018LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2023037911LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2023037912

Cover Design: WileyCover Image: © thanasak/Adobe Stock Photos; © owngarden/Getty Images

For Earl

A Taste of Athens

Nate’s favorite restaurant means a great deal to him. Not because it’s cool. In fact, A Taste of Athens is dumpy and sad, and their dips look like piles of vomit. The good news is, they taste a lot better than they look. The restaurant is also where the Shelley family celebrates birthdays, anniversaries, and every other important event in their lives. All of that makes it even better than cool.

A Taste of Athens, like Sharon’s transformer bike, reminds us there’s often more to most things than meets the eye. You might even say that the restaurant provides a window (table) into issues relevant to another Athens, the birthplace of philosophy.

The comparison’s no joke. We can’t wait to unpack it with you.

The colorful and charming Ted Lasso premiered amidst a pandemic so dire you’d think the Wichita State Shockers tried to end a game in a tie. The show’s optimism and sweetness during those dark days came as a bit of a tonic. This fizzy water went down surprisingly smooth, and soon the beloved characters and clever writers captivated audiences, earning Ted Lasso lots of beautiful, shiny awards and loads of critical acclaim. At moments it almost seemed to be an antidote to the acrimony and angst of our time.

For a series in so many ways easy to watch—usually light and lots of fun—Ted Lasso features more nuance, depth, and philosophical resonance than its vibrant veneer suggests. The nature of true success, the role of mental health, sportsmanship, revenge versus justice, the importance of friendship, the imperative of respect for persons, humility, leadership, identity, character growth, courage, journalistic ethics, belief, forgiveness, and what love looks like: these are all topics broached by the show, plus much more.

That said—not to tinkle on anyone’s toenails—the show is far from perfect. At times, it’s uneven (looking at you, Season 3). It has its highs and lows, its depths and superficialities, its epiphanies and blind spots. By turns it can be inspiring and predictable, iconoclastic and formulaic. Ted Lasso has attracted die‐hard fans, as loyal as Basil, Jeremy, and Paul are to the Greyhounds. But it also has its detractors who counter the accolades with charges of shallowness and schmaltz.

Fortunately, this book is not about the philosophy of Ted Lasso. Rather, it’s Ted Lasso and philosophy. In the great dartboard scene in Season 1’s “Diamond Dogs,” Ted talks about how people had long underestimated him. They let judgmentalism crowd out their curiosity and shut down fruitful questions. Philosophy by contrast celebrates questions and begins in wonder. It peels back all the juicy layers of appearance to discover the reality that lies beneath. That’s exactly what we intend to do here: using the show, whatever its faults, as a springboard for philosophical reflection.

Those who have watched Ted Lasso, featuring biscuits‐with‐the‐boss, finger allergies, and exorcisms of training rooms, find its defiance of low expectations more than fitting. Like a candy bar little Ronnie Fouch might offer you on the playground, it invites further investigation.

Ted Lasso is surely a book you don’t want to judge by its cover, lest you miss out on an undiscovered mega‐talent. On its surface, it’s about (English) football and a cheerful, guileless, displaced American working abroad. But as Trent Crimm wisely observes, sport is a metaphor for life. There’s certainly more to Ted Lasso himself than first appears. Relentlessly optimistic and happy‐go‐lucky, Ted navigates complicated feelings and deep trauma from his past. For those like Dr. Fieldstone “only interested in the truth,” this book can help diagnose Ted’s tears, and a whole lot more.

Other characters are equally complex. At first Nathan Shelley seems an unimpressive kit man, awkward and bumbling, when in fact he turns out to be a football genius. Rebecca Welton initially acts like she sees something in Ted that her team needs to get to the next level, when in fact her motivation is to hire Ted to destroy its prospects. Jamie Tartt begins as an obnoxious self‐absorbed superstar, but he eventually reveals his deep yearning for meaningful connections with others.

Sometimes appearance/reality gaps in Ted Lasso result from revising history, sometimes from intentional deception, and sometimes from too static a conception of characters. Our worst moments don’t define us, and there’s a great dynamism in Ted Lasso when it comes to the maturation of its characters. Ted, especially, helps those around him to become better people, the best versions of themselves both on and off the field.

Ted himself has to come to terms with aspects of his past that make him as haunted as Richmond’s training room. He too needs help from his surrogate family. This makes the show fascinating from a psychological perspective, but also from a philosophical one. It’s a show that continually challenges viewers to look beyond surface differences and misleading appearances that too often divide or prove destructive. It also resists too‐simple categorizations, reminding us as Beard might say that “all people are different people” (“Goodbye Earl”). For those with eyes to see, Ted Lasso can help us look right.

We’re sad to see Ted Lasso come to a close. Nelson Road is a delightful world to inhabit. The creators do have a tendency to surprise us, though, so whether or not this truly is the end remains to be seen.

The chapters to come, whose titles at times are intentionally as opaque as Keeley’s office window, are divided into five sections: (a) Do the Right‐est Thing, which touches on Augustine, Taoism, precursive faith and the ethics of belief, and ethical egoism; (b) The Best Versions of Ourselves, dealing with issues of fear, competitive excellence, psychological health, and coach/athlete friendships; (c) Man City, canvassing masculinity, gender, the relative importance of winning, and “bullshit”; (d) Mostly Football Is Life, touching on music in Ted Lasso, the possibility we’re in a simulation, insights from Candide and Camus, and Chestertonian optimism; and (e) Smells Like Potential, covering journalistic ethics, Stoicism, respect for others, and whether Rupert is beyond redemption. “Beard’s Bookshelf” closes the volume by chronicling the books Coach Beard (and others) are reading throughout the series.

We’re indebted to our wonderful contributors who met deadlines tighter than Coach Beard’s thong. We’re also grateful to the team at Wiley Blackwell who believed in this project from the start, and especially to William Irwin, whose support has been characteristically both brilliant and unstinting. And we’d be remiss not to recognize our friend Michaela Flack whose early delight in Ted Lasso sparked our own and whose enthusiastic support of our work enriched this project.

So pull up a seat. A taste of Athens awaits, no reservation required. Look past the seemingly rude hostess, the annoying manager, and the snooty diners, and you’ll find a feast for the heart and mind. The baklava, we’ve heard, is divine.

Metaphor? Exactamundo, Dikembe Mutombo.

Part IDO THE RIGHT‐EST THING

1On the Pitch with Saint Augustine

Sean Strehlow

“What do you love?”

Ted asks Trent Crimm this simple question during the third episode of Season 1. Ted follows up with his own answer: “I love coaching. For me, success is not about the wins and losses. It’s about helping these young fellas be the best versions of themselves on and off the field” (“Trent Crimm: The Independent”). This notion that coaching can prepare athletes for life on and off the field echoes a strong cultural sentiment that participation in sport builds character. But when setting out to define “character,” concrete definitions are difficult to pin down. Ted’s definition of the offsides rule may well apply here: “I’m gonna put it the same way the US Supreme Court did back in 1964 when they defined pornography. It ain’t easy to explain, but you know it when you see it” (“Biscuits”).

One reason character is such an elusive notion is that it is rarely reducible to its readily observable dimensions. As a simple exercise, imagine one of several scenes in Ted Lasso where the Richmond team is working out in the weight room. We can assume that every athlete enters the weight room with a set of intentions, or goals, for their workout. Some athletes may be working on rehabbing an injury, while others may be looking to strengthen a particular muscle. Each athlete also shares a larger goal of improving his individual and team performance. Some (ahem… Jamie Tartt) may be more concerned with their physical appearance than anything else. How these intentions are ordered shapes the way the athletes engage in their workout.

As the above scene illustrates, our behaviors are made meaningful by our intentions, our goals or purposes that provide motivations for our actions. These lie close to our affective center. When evaluating a person’s character, we might begin with behaviors we can directly observe, or the reasoning that led to those behaviors. But what is infinitely more complex, and what forms our cognitive and behavioral patterns, is what Ted’s opening question highlights. More than anything, our character is defined by our heart—it is dictated by what we love.1

What Is Love?

One of the challenges and opportunities for philosophy and the clarity and rigor it seeks is the transient nature of language across time and place. Or, as Ted would advise, best not to smother English biscuits in gravy (“Biscuits”). Today, images related to love and the heart typically evoke a kind of sentimentality one might find in a Hallmark card or romantic comedy (“rom com”). Love is a rather degraded notion in common parlance. Reviews of Ted Lasso regularly feature a similar “heartwarming” emotivism.2 When ancient philosophers refer to the heart, though, it often carries the same weight as the Greek word kardia, which more accurately might be described as the soul—the spiritual epicenter of our deepest, most fundamental, longings and desires.

The heart (kardia) is an unavoidable part of the human experience. By asking Crimm about what he loves, Ted communicates the philosophical truth that the key question is not whether we love, but what we love. Perhaps no one knew this better than Saint Augustine of Hippo (354–430), a North African Bishop whose writings remain essential to the Western philosophical tradition. Augustine belongs to a long line of philosophers, beginning with Aristotle (384–322 BC), who see happiness as the ultimate human aim. This is to say, all human activity is aimed at achieving a state of stable and sustainable happiness, understood in a robust and substantive way. For Augustine, happiness is inextricably tied to what we love.

To complicate matters, we have many loves that compel us to think and act in different, often conflicting or dissonant, ways. Consider the morally ambivalent Rebecca, whose desire to enact revenge against Rupert eventually clashes with her growing affinity for the Richmond Football Club and for Ted himself. As these two passions fluctuate in Rebecca’s heart, her actions realign with the one that takes primacy. This prioritization is what Augustine refers to as the ordo amoris, the ordering of loves, which

requires one to be capable of an objective and impartial evaluation of things; to love things, that is to say, in the right order, so that you do not love what is not to be loved, or fail to love what is to be loved, or have a greater love for what is to be loved less, or equal love for things that should be loved less or more, or a lesser or greater love for things that should be loved equally.3

Drawing on this concept, we can think of our heart as an ecosystem of desires that are constantly competing for our attention. Augustine described our desires as having their own gravitational pull that prompts us to think and act in certain ways: “My love is my weight! I am borne about by it, wheresoever I am borne.”4 When faced with difficult decisions or moral dilemmas, our most deep‐seated desires “win out” to provide the motivation for our actions.

The Ordo Amoris in Ted Lasso

“Two Aces” most vividly captures this spirit in Ted Lasso. This is the episode of the training room curse. More importantly, it is the episode introducing the ebullient Dani Rojas. If Ted is the show’s most loveable character, Dani must be a close second. His infectious joy seems to permeate the entire show, demonstrating that one can, in fact, “give away joy for free” (“Diamond Dogs”). Avid Ted Lasso fans will be familiar with Dani’s mantra, “Football is life!” But there is another Richmond player who wears this mantra on his sleeve, even if he doesn’t say it out loud—Jamie Tartt. In fact, Ted says this explicitly while yelling at Jamie for missing practice:

We’re talking about practice. You understand me? Practice. Not a game. Not a game. Not the game you go out there and die for. Right? Play every weekend like it’s your last, right? No, we’re talking about practice, man. Practice!

Indeed, both Dani and Jamie love football as if it is life itself, but in very different ways.

Augustine can strengthen our analysis here. Jamie’s love for soccer resembles what Augustine refers to as cupiditas or cupidity, a disordered love. This kind of love is self‐serving because its intention is self‐gratification, even at the expense of others. Ted’s tirade about missing practice is a crucial moment because, for the first time, Jamie is directly confronted about this disordered affection. Notice what happens immediately after Ted puts Jamie in his place. Colin takes a jab at Jamie for being a “second‐teamer” and Isaac backs him up. Until that moment, they idolized Jamie, another example of cupidity. With Jamie’s change of fortunes, among a group of athletes with their own desires bouncing every which way, the gravitational center of their collective desires shifts ever so subtly toward the good of the team.

Immediately afterwards comes Dani Rojas, whose love for football is enlivened by a different intention. This type of love is what Augustine refers to as caritas, a rightly ordered love that finds pleasure and satisfaction in the good of others. Not only does Dani repeat his mantra. He also demonstrates it to the coaches (“You say it, I do it, coach!”) and to his teammates by attributing his goal to their efforts. Dani further shows this kind of love during his post‐practice shootout with Jamie—admiring Jamie’s shots and attributing his own success to luck. We might more accurately interpret Dani’s mantra as “football is life giving.” This newfound source of talent, energy, and concern for others leaves a noticeable impression on the team and the center of gravity shifts yet again.

Later, when the Richmond team gathers for the ceremony to get rid of the ghosts in the training room, Rebecca inaugurates another affective shift. In her obsession with getting revenge on Rupert, Rebecca had exemplified what Augustine calls cupiditas—a disordered love of something that should not be loved at all. Throwing the newspaper with Rupert’s headline into the trash can symbolizes a shift to prioritizing Ted and the Richmond team, even if it takes a little while to stick.

Jamie, too, uncharacteristically opens up about his painful past. We see his disordered love for football begin to shift ever so slightly. In fact, we can look at everyone’s sacrifices, even the silly ones (like Richard’s memento from his maiden voyage with a supermodel), as a reordering of loves. Each object represents a source of self‐gratification and comfort that their owners had valued above all else. The ghosts in this episode may not have been real, but there is something quite enchanting and transcendent, even supernatural, about an entire group of people giving up what means most to them for something that might benefit the group.

Worship at Crystal Palace

Ordering our loves is never a linear process, however. Jamie retreats back into himself when he’s recalled by Manchester City. Rebecca still waffles back and forth in her desire for revenge. Even Nate finds his own dark path in his disordered love for status and respect. In Season 3, we also see a disordered collective love, centered on Zava. In this instance, the team seems to think the Russian phenom will save their season, but in fact, the redemptive arc does not begin until the team learns to play without him.

A challenge to an Augustinian analysis of Ted Lasso is that Augustine’s philosophy was painstakingly theocentric. For Augustine, without a proper love of God, even our most noble and selfless intentions can become disordered. In the opening paragraph of his Confessions—a spiritual autobiography written as a form of prayer—Augustine describes humans as restless creatures. He proclaims to God, “You have made us for yourself, and our heart is restless until it rests in you.”5 Without God, by Augustine’s lights, when one desire fails to deliver on its promise to make us happy, we wander “restlessly” to the next.

Augustine saw liturgy, a ritualized form of public worship, as a way to train and transform the heart so that it desires God and God’s will above all other desires. For this reason, the contemporary philosopher James K. A. Smith urges us to think about our seemingly banal routines as cultural liturgies that shape our desires and order them toward some ultimate intention. One only need observe the religious language (“church,” “pray,” “transubstantiation,” “collection plate”) used to describe Roy’s favorite kebab shop to get a sense of how important our routines can be. Smith argues that “thick” ritual practices (like sports) constitute liturgies because of their ability to “inscribe” a vision of the good life onto our hearts.6 In this way, professional sports are extremely formative liturgies. At bottom, highly competitive sport can inculcate a desire to win that reorders our entire lives.

The pub‐crawling trio—Paul, Baz, and Jeremy—are the perfect representatives of a large swath of sports fanatics who live and die by the success of their team. Week in and week out they adorn themselves with special attire and gather in droves at houses, pubs, and stadiums to begin the opening ceremonies. There is a rhythm to their practice: a time to sit and stand, to scream, to sing, to embrace others around you, to celebrate, and to mourn. Keeley has memorized it, even though she never really cared for football herself. Still, she knows “how to act at a match,” including when to dub a referee a turnip (“The Hope That Kills You”). Through these rituals, we learn to hope (or not to hope) in a highly anticipated future. That future is an image of victory—of the good life—that is “willing to make room for additional loyalties, but it is not willing to entertain trumping loyalties.”7

This image is never just about sports. It includes a wide range of narratives that define what it means to be fully human. Writing on the tight coupling between winning and national identity in capitalist societies, Hugh Mackay once observed of Australia, his home country:

Our sporting impulse encourages us to think about economic growth or globalization, or industrial relations reform, in terms of winning; our spiritual impulse drives us to think about equity, fairness, and justice, and about the impact of our success on the poor, disadvantaged, the marginalized. In a culture that almost deifies competition, the sporting urge prevails most of the time.8

What better image of this in Ted Lasso than the ideological clash between Cerithium Oil and Sam’s civic identity as a Nigerian? (“Do the Right‐est Thing”). By protesting Dubai Air, his club’s sponsor, Sam challenges the longstanding virtues and values embedded in one of England’s richest cultural liturgies. These moral assumptions are also embodied in Edwin Akufo, whose unbridled capitalistic ambition is certainly a disordered love. Sam’s moral courage in the face of Dubai Air and Akufo shows that without a more transcendent narrative, outcomes—on the field or in the market—become disordered as an ultimate concern.

When winning becomes an ultimate concern, the liturgy of competitive sport reinforces the myth that our worth and value stem from what we are able to produce, rather than an inherent human dignity that we all share. In Augustine’s tradition, the tendency to find one’s value in a sub‐ultimate good, like athletic success, is a form of idolatry. Though not everyone would describe this tendency in those terms, the negative effects are obvious. Take Roy’s initial inability to come to terms with his retirement. This phenomenon, known by social scientists as identity foreclosure, is prevalent in highly competitive athletes when they reach the end of their career.9 Without counter‐liturgies to remind us of our worth and value, we are extremely dependent on relationships with other people who can remind us of these truths.

Saints and Scamps

Augustine was well aware of the influence that others can have on us. In his Confessions, he recalls a friend, Alypius, who allowed others’ disordered love for the violent spectacle of Roman gladiatorial games to draw him in. Alypius arrived in Rome with an aversion to these games, but “[h]is friends and fellow students whom he chanced to meet as they were returning from dinner, in spite of the fact that he strongly objected and resisted them, dragged him with friendly force into the amphitheater on a day for these cruel and deadly games.”10 Not only did Alypius become a willing participant in this activity. He also became one who, like his friends, recruited others to join.

The lesson here is that ordering loves always takes place in community. To some extent, the character of the individual will start to resemble the character of the communities they become a part of. Other chapters in this volume explore the influence of coaches and peers in some form or fashion as one illustration. The example here is a different relationship: fathers and father figures.

The pain of an absent father is a common Hollywood trope, and one that Ted Lasso employs on a variety of levels. The theme is so pervasive it can even be seen in the appearance of John Wingsnight, Rebecca’s underwhelming date in “Goodbye Earl.” During their outing with Roy and Keeley, John mentions Roy’s retirement speech, noting: “It’s the first time my father’s forwarded me an email in the last five years that wasn’t about the scourge of immigration. And that really meant a lot to me, so thank you.” This universal longing of a son for a connection with his father fuels most cinematic takes on the father‐son relationship (including my personal favorite, October Sky).

Sadly, in Ted Lasso this longing often goes unsatisfied. Nate’s development from timidity to overconfidence makes sense only in light of his father’s reluctance to offer encouragement and affirmation. His arc also shows the ease with which the right amount of love can, by quick turns, be missed by either excess or deficiency in the same person. This theme is especially prominent in Jamie’s development. During the de‐ghosting ceremony in “Two Aces,” he finally reveals the neglect of his father as the root of his behavior. Toward the end of the first season, and later in the second, we get a graphic picture of this reality when we meet the abrasive and abusive James Tartt and witness his impoverished moral character. It is suddenly easy to imagine how Jamie became the way he presents himself throughout most of the show. Deprived of the unconditional love of their fathers, both Nate and Jamie look for ways to fill the void.

We also see several positive examples of fatherhood in the show, the most obvious of which might be Ted’s love for his own son, despite their painful physical distance (4,438 miles to be precise). Or the relationship between Sam Obisanya and his dad. The first hint of this relationship appears before Richmond’s first game against Crystal Palace during a surprise birthday celebration for Sam. In a brief endearing moment with Ted, Sam recalls a memory of his father sparked by Ted’s kindness toward him (that Jamie scoffs at). In Season 2, Sam’s father reappears to reprimand Sam for his involvement with Dubai Air, and, by extension, Cerithium Oil. In this exchange, Sam’s father is teaching a valuable lesson about what really constitutes the good life, and his disappointment in Sam is not connected to his performance, but his priorities. This is evident in a later phone call between Sam and his father in “Man City,” near the end of Season 2. Sam’s father expresses how proud he is of Sam and ends the call with a heartfelt “I love you.” The director again calls attention to Jamie’s disappointment and jealousy upon overhearing the conversation.

What we learn from these examples is that, in the face of cultural liturgies that conflate winning and worth, fathers have an outsized ability to help young men order their loves. Good fathers teach their sons to be a part of something larger than themselves. The great ones teach their sons to look beyond sports and toward something more ultimate. C. S. Lewis (1898–1963) echoed this sentiment when describing his mentor, George MacDonald (1824–1905): “An almost perfect relationship with his father was the earthly root of all his wisdom. From his own father … he first learned that Fatherhood must be at the core of the universe.”11

Ted Lasso: The Father We Never Had

Like Jamie and Nate, Augustine didn’t have much of a father growing up. Augustine’s father, Patricius, sported a history of alcoholism, abuse, and infidelity before his late conversion to faith on his deathbed. Augustine was only seventeen years old when his father died, but he found a father figure in Saint Ambrose, the bishop of Milan, who was a fierce advocate for the church against the heresies of the day. Ambrose nurtured Augustine into the formidable philosopher and theologian he eventually became, but it began with a kindness and compassion that drew Augustine in. There’s the family we’re born with and the family we gain along the way.

Ambrose was a father figure to Augustine in a similar way that Ted acts as a father figure to his athletes. What is most striking about Ted is his lack of regard for the one thing that most other characters in the show value above anything else: winning. Years of engaging in the formative liturgy of soccer had trained the Richmond team to reject Ted for his demeanor and attitude toward the sport. Slowly, though, Ted wins their affections through a relentless and thoroughgoing kindness that all children long to receive from their fathers.

The parallel between the father‐son and coach‐athlete relationships is most evident during Ted and Roy’s conversation at the kebab shop in “Rainbow.” The store owner mistakenly takes Ted and Roy as father and son. When Ted clarifies that he is Roy’s former coach, the distinction is brushed off: “It’s all the same thing.” The interaction prompts the owner to reflect on his relationship with his own father, which echoes a similar dynamic between Ted and Roy. Ted notices potential in Roy that all good fathers recognize in their own sons, and he gently and lovingly guides Roy to see what he sees.

Fathers and father figures play a central role in the ordering of loves throughout the show. Just as Ted is a father figure to Roy in Season 2, Roy assumes a similar role for Jamie in Season 3. When the pair go out for a beer in “So Long, Farewell,” Jaime tells Roy: “Thank you for your help too, you know. For motivating me, encouraging me. I haven’t really had that from the older men in me life.” In the same way, the mended relationship between Nathan and his father is the catalyst for the Wonder Kid’s redemption in the final season. In both of these instances, the presence of a father figure helped the characters reorder their loves and loyalties in a way that helped them, and the Richmond club, flourish.

In the last analysis, Augustine would not much approve of the commercialized and politicized nature of sport as portrayed in Ted Lasso. He would likely be repulsed at the vanity and vulgarity of it all. At the same time, Augustine would be fascinated by the coach‐athlete relationship as a vehicle to care for the fatherless. Because of his openness to something transcendent, Augustine might well smile down on coaches like Ted Lasso. Indeed, he understood how the love of an earthly father can open a child’s eyes to deeper truths.

Notes

1

Although I will be drawing directly from St. Augustine in this analysis, the works of contemporary philosopher and Augustine interpreter James K. A. Smith have also greatly influenced my own thoughts in this chapter.

2

Proma Khosla, “Everyone’s an MVP in Heartwarming ‘Ted Lasso’ Season 2,”

Mashable

, July, 23 2021, at

https://mashable.com/article/ted‐lasso‐season‐2‐review‐apple‐tv

.

3

Augustine,

Teaching Christianity

or

De Doctrina Christiana

, trans. Edmund Hill (New York: New City Press, 1996), 118.

4

Augustine,

Confessions

, trans. John K. Ryan (New York: Doubleday, 1960), 341.

5

Ibid., 43.

6

James K. A. Smith,

Desiring the Kingdom

(Grand Rapids: Baker Publishers, 2009), 82–83.

7

Ibid., 106–107, emphasis original.

8

Hugh Mackay,

Turning Point: Australians Choosing Their Future

(Sydney: Pan Macmillan Australia, 1999), 234–235.

9

Britton W. Brewer and Albert J. Petitpas, “Athletic Identity Foreclosure,”

Current Opinion in Psychology

16 (2017), 118–122.

10

Augustine,

Confessions

, 144.

11

C.S. Lewis,

George MacDonald: An Anthology

(New York: HarperCollins, 2009), xxiii.

2Isaac Finds His Flow

Elizabeth Schiltz

One of the most iconic moments in Ted Lasso occurs in the episode “Man City,” when Sam requests, and receives, his once‐a‐season “Isaac cut.”

The team gathers in hushed anticipation as the strains of “La Virgen de la Macarena” swell and Isaac readies his clippers. The mood, however, shifts into joyous appreciation as Isaac begins to demonstrate his skill. He seems to have a deeply intuitive sense of where and how to cut, and he carries out his work with a flourish and rhythm that matches the glorious Mahalia Jackson’s “Down by the Riverside” playing in the background. The Greyhounds erupt into cheers, applause, and laughter at every exquisite sweep of the clippers and snip of the scissors. Even an initially skeptical Jan Maas can’t resist an enthusiastic response. As Colin says: “It’s like Swan Lake!”

This is indeed a thrilling scene, one that represents both an important moment in Isaac’s character arc and a significant signal in the development of a unified AFC Richmond. At the beginning of Season 1, we meet Isaac as part of the gang who harass a defenseless Nate to amuse a smirking Jamie Tartt. By the end of Season 2, he is the artful captain whose gentle tap on the “Believe” sign inspires our Greyhounds to a rebound against AFC Brentford, and to a promotion back to the Premier League. How should we think about this transition? How does Isaac’s mastery with his clippers reflect his developing approach to soccer—and life? What does this approach signal for his leadership of our team?

Our beloved team captain is certainly exceptional, but there are classical antecedents for his character, development, and skill. Consider this description of a masterful butcher from the 4th century BC Daoist philosopher Zhuangzi:

Wherever his hand touched, wherever his shoulder leaned, wherever his foot stepped, wherever his knee pushed—with a zip! With a whoosh!—he handled his chopper with aplomb, and never skipped a beat. He moved in time to the “Dance of the Mulberry Forest,” and harmonized with the “Head of the Line Symphony.” Lord Wenhui said, “Ah excellent, that technique can reach such heights!”1

This chapter will argue that we can usefully understand Isaac’s character arc in terms of an ongoing development of his Daoist sensibilities. Further, Isaac’s virtuosity—as a barber, player, and leader—reflects the potential utility of a kind of Zhuangzist approach to the world.

The Dao of Isaac

Isaac, like Zhuangzi, is an original.

Isaac is a unique presence on the Richmond team. Ted’s first, astonished assessment is a good one: Isaac is truly a “Rodin sculpture in cleats.” He combines physical and skilled defensive work with a keen understanding of the game in such a way as to allow him to play a key role in the Greyhounds’ success. In “The Signal,” it is Isaac who organizes the team into “parking the bus,” and so sets the stage for the Tottenham error that leads the Greyhounds to a thrilling FA Cup quarterfinals win. In “The Hope that Kills You,” Isaac’s quick assessment of the opportunity created by an extra time free kick—and his spontaneous organization of the team into the “Lasso Special” trick play—garners the crucial equalizer. In “So Long, Farewell,” it is Isaac’s “superhuman foot” that sends the penalty kick through the net, and sets our Greyhounds up for a glorious victory over Rupert and West Ham.

In similar ways, Zhuangzi is an atypical philosopher. The text that purports to present his thinking, called the Zhuangzi, stands out among the works in the philosophical canon.2 Instead of straightforward theses or systematic essays, the Zhuangzi confronts us with fantastical beasts, silly stories, cheeky conversations, and mystifying claims, expecting us to draw our own philosophical conclusions. The text also introduces us to Zhuangzi himself. We see Zhuangzi puzzling, perplexing, and disorienting those he meets, and, by extension, his readers as well. His singular style is all to the good, however. As Roger Ames asserts, the Zhuangzi is “one of the finest pieces of literature in the classical Chinese corpus … an object lesson in marshaling every trope and literary device available to provide rhetorically charged flashes of insight into the most creative way to live one’s life in the world.”3

Isaac and Zhuangzi don’t just share an originality in their vocations. They also have some important personal characteristics in common. Both seem utterly candid in their responses to events and people, and are not at all bothered at the prospect of appearing silly or confounding expectations as a result. Think, for example, of “Two Aces,” where we see Isaac’s honest reaction to learning both about the ghosts in the training room, and about Ted’s surprising plans to honor them. That look of genuine puzzlement finds its analogue in Zhuangzi’s response to a dream about being a happy butterfly—which has left him unsure whether he is Zhuangzi awakening from a dream that he was a butterfly or is a butterfly now dreaming he is Zhuangzi. In the same way, Zhuangzi, whose friends were astounded to find him beating on a tub and singing during what should have been a period of mourning, could surely have appreciated Isaac’s star turn as an unconventional Santa in a magnificent red velour suit in “The Carol of the Bells”.

In addition, both Isaac and Zhuangzi are kind to others and deeply responsive to their individual qualities and needs. They are often particularly attentive to those whose status is lower than their own. While Isaac initially picked on Nate, the team’s timid kit man, we see him quickly develop care and compassion for him. By the fifth episode of the series, we find him silently making room for a surprised Nate on the team bench, and then carefully carrying the inebriated kit man out of a karaoke bar. Further, in “Make Rebecca Great Again,” he gently encourages Nate to deliver his pre‐game speech. The speech, as it turns out, inspires the team to a long‐awaited victory over Everton. In a similar way, the Zhuangzi provides sympathetic, philosophical portraits of many who might not have been esteemed by society, such as the invalid, the amputee, and the “Out‐of‐Step Woman.” This attention, too, is both meritorious and valuable. In their recent New York Times editorial, “Was This Ancient Taoist the First Philosopher of Disability?” John Altmann and Bryan Van Norden argue that “Zhuangzi is an important and insightful guide … to challenge our conventional notions of flourishing and health.”4

The commonalities go deeper. Isaac and Zhuangzi also have a similar approach to the world: both avoid unnecessary complexity. As a player and as a person, Isaac seems to focus on one thing at a time. He is utterly dedicated to the success of the team, and, when, as in “The Diamond Dogs,” he is pushed to name another thing he likes, he names “Rolos … Just Rolos, yeah.” Isaac’s speech is always direct and brief. He is a man who will not give a long speech when a “You’ve got this bruv” will work. In fact, he will not use any words at all when an angry expression or chair through a TV will make his point just as well. He is also completely without guile. As we learn in “La Locker Room Aux Folles,” he is transparent in a way that renders him incapable of keeping secrets. He is forthright to a fault.

Zhuangzi reflects a similar mistrust of complexity. His commitments do not involve Rolos, but rather the single and ultimate dao. Alas, this is a slightly more abstruse concept, one that has developed in multifarious ways. The word “dao” initially referred to a road or path. In early Chinese thought, however, its meaning expanded from a reference to actual paths or “ways,” to a “way” the world is.5 This dao is not static, though. Like the world, it is constantly changing. As the earlier Daoist philosopher Laozi put it: the Way is like water, “flowing to the left and the right.”6

The idea that there is a dao, then, was not unique to Zhuangzi. Many Chinese philosophers sought to describe both this “Way,” and how we can best live in accord with it. The Confucians, for instance, encouraged the thoughtful and appropriate participation in traditional arts, rites, rituals, and properly hierarchical relationships as a means of achieving harmony with “the Way.” The Analects show Confucius engaged in deep conversations about the utility of these means for our development of crucial virtues such as benevolence and righteousness. As such, the text points us towards a particular style of human life: “The Master said, Set your heart on the dao, base yourself in virtue, rely on benevolence, journey in the arts.”7

Zhuangzi, however, develops the idea of the dao in a different and fascinating way. In the text that bears his name, we see him suggest that this dao is not human, but natural. Further, while it is conceptually linked to “Heaven,” he insists that it is inherent in our world: “Where is this so‐called Way?” A question he quickly answers: “There’s nowhere it isn’t.”8

Of course, if, like Roy Kent, the dao is here, there, and everywhere, we don’t need to employ extensive analysis or ornate procedures to access it. Indeed, insofar as language relies on drawing fixed distinctions between things, it is hard to see how it could capture the flowing dao. Even worse, since language is a complex human innovation, engaging in lengthy elaborations and detailed discussions may well serve to lead us away from the simplicity and naturalness of the dao. Instead, the Zhuangzi suggests a process of forgetting all of that. Ted’s goldfish has nothing on our new friends:

Yan Hui said, “I’m improving.”

Kongzi said, “How so?”

“I’ve forgotten benevolence and righteousness.”

“Good, but there’s more.”

Yan Hui saw him again the next day and said, “I’m improving.”

“How so?”

“I’ve forgotten rites and music.”

“Good, but there’s more.”

Yan Hui saw him again the next day and said, “I’m improving.”

“How so?”

“I sit and forget … leave my form, abandon knowledge, and unify them in the great comprehension.”9

I am, of course, not suggesting that Isaac is a student of Zhuangzi’s Daoism, though who knows? The man is a mystery. The suggestion is simply that Isaac reflects the kind of Daoist sensibility we have been discussing. One can imagine Isaac as just the person Zhuangzi is looking for:

A snare is for rabbits: when you’ve got the rabbit, you can forget the snare. Words are for meaning: when you’ve got the meaning, you can forget the words. Where can I find someone who’s forgotten words so I can have a word with him?10

Isaac, like Zhuangzi, is about the meaning, not the words. Further: we can understand our captain’s character arc in terms of a continuing development of his Daoist sensibilities.

“Do without Ado,” McAdoo!

Of course, the ultimate point of the Zhuangzi isn’t to present and defend a view of “the Way.” Instead, all of these stories and suggestions aim at poking and prodding us into figuring out how we, as individuals, can best live in accord with the flowing dao. To that end, Daoist thinkers introduce a new and challenging suggestion: we should engage in wu‐wei, or “effortless” action.11

Think about it like this: sometimes, when we try very hard at something, we get in our own way, and end up failing even more