9,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Salt

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

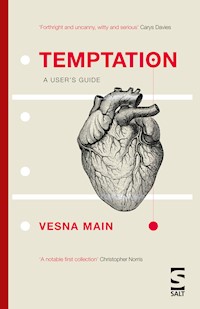

Variations and fugue on the theme of obsession Vesna Main disturbs our self-image as educated, reasonable and ironic people who read modernist fiction. She disturbs us because we recognise ourselves in her obsessive and bloody-minded characters as they are pushed to the extreme. But they are only too human and seek love, just like us. This is a collection of twenty short stories of different lengths and written in a variety of styles. Main writes about characters whose passion borders on obsession and who are seeking love and companionship but are doomed to remain alone, with their sense of personal failure as the only company.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

TEMPTATION: A USER’S GUIDE

by

VESNA MAIN

Variations and fugue on the theme of obsession

Vesna Main disturbs our self-image as educated, reasonable and ironic people who read modernist fiction. She disturbs us because we recognise ourselves in her obsessive and bloody-minded characters as they are pushed to the extreme. But they are only too human and seek love, just like us.

This is a collection of twenty short stories of different lengths and written in a variety of styles. Main writes about characters whose passion borders on obsession and who are seeking love and companionship but are doomed to remain alone, with their sense of personal failure as the only company.

PRAISE FOR THIS BOOK

‘Vesna Main’s short fictions have all the truly experimental virtues: wit, inventiveness, formal ingenuity, sharp-eared dialogue, thematic range, and marvellous economy of narrative means. A notable first collection.’ —CHRISTOPHER NORRIS

‘By turns forthright and uncanny, witty and serious, Vesna Main’s stories interrogate our difficult world. With their cast of prostitutes, prisoners, husbands, wives, exiles, misanthropes and writers, they ask questions about intimacy and love, ageing and death, about solitude and identity and the transformative power of art.’ —CARYS DAVIES

Temptation: A User’s Guide

VESNA MAIN as born in Zagreb, Croatia. She studied comparative literature before obtaining a doctorate from the Shakespeare Institute in Birmingham. She has worked as a journalist, lecturer and teacher. Her two novels are A Woman With No Clothes On(Delancey Press, 2008) andThe Reader the Writer (Mirador, 2015). The latter is written entirely in dialogue and one of the characters is a young prostitute who is also the protagonist of ‘Safe’. Recent short stories have appeared inPersimmon Tree andWinamop.

In memory of my parents, and my friends Manuel Alvarado, David Potter and Max Lab

‘It is strange that no reader ever understood that my only subject is love.’

ALBERTO MANGUEL, All Men Are Liars

Safe

IT WAS HER time now. She was safe. She could leave. No one would stop her. She doesn’t have to see him again. She knew all that and yet the voice kept repeating the same thing. But something else, not a voice, a force inside her wouldn’t let go. That force made her fetch a knife from a drawer in the kitchen. That force made her walk back to the room. That force made her push the blade into Dave, lying sprawled on the floor, snoring. As the steel cut into his chest, he jumped, startled, uttered a cry, of shock or anger – she couldn’t tell. Fear ripped his eyes open. He lurched to one side, shaking, trying to grab her, mad from pain. But he was drunk with beer and sleep and she was quicker. She stabbed him again. And then she stabbed Marvin and saw his kind, lined face grimace with pain. And again. And again she had it for Dave. Quick, sharp stabs. In out, faster and faster, like someone going mad chopping onions. Each time she shoved home the knife, his blood spurted its red warmth onto her face, onto her half-naked body, onto the walls around them. It dripped on the carpet; she could feel its drying stickiness on the skin between her toes. Her hand moved as if someone was directing it, pushing it with a long stick as if she were a puppet. And the hand carried on working for a long time after he had stopped making any sound. All she could hear was the swish as the knife passed through his chest. When she stopped, she was gasping for breath. The swish continued. His body lay next to her like a huge wet sponge. The hard work was over. She could relax. She fell backwards into an armchair, her legs stretched out. She had no energy left, her body a rag doll. If he could get up now, she wouldn’t be able to fight back. She was certain of that. But he was more dead than the corpses she had seen on the telly. She closed her eyes. She was safe. It was her time now.

She must have dozed off. When she woke up, the blood on her skin had dried. There was daylight and the sun hurt her eyes. Her body shivered with cold. She screamed when she saw him: his eyes bulging like in a horror film. She rushed out of the room. Was he still alive?

She should wash her hands, her body, the carpet, the walls. And him? If he were dead, she could take him somewhere. Hide him. But she wouldn’t do any of that. She had killed him. She was going to jail. And then she saw him, a big body stumbling towards her, his eyes bleeding sockets. But the face was kind, the face of Marvin, lined. He was smiling, putting out his hand towards her, checking that her body was warm. Marvin, her mother’s friend, who bought her ice-cream, who made sure that she was warm inside and down there. Marvin was kind. But his fingers were cold, bony, an old person’s fingers. Not like Dave’s, Dave’s fingers chubby like sausages. Marvin was kind. Kind to her. Kind to her mother. Why was his face the same as Dave’s? She grabbed her coat and ran into the street. She ran, her bare feet slapping the cold tarmac. Dave lumbered after her. She ran until she couldn’t see him. But she knew he would come and she was scared.

She banged on the door of a house. She banged and called until a window opened in a room upstairs. And another one in the neighbouring house. A door unlocked and she rushed in. The rest happened to someone else and she watched it from the side without feeling a thing. People in the house, a police ride, a station, questions – she couldn’t tell what they had to do with her – but the questions, so many questions and a doctor who came to examine her for wounds, samples of blood they took and then a shower. She sat on a cracked tiled floor and let the water run over her head, over her hunched body. She saw herself jumping away from Dave as he pulled off her bra and threw it to Nige. She crossed her arms to cover her naked breasts. Nige sniffed her bra. The other man was laughing loudly and banging his fist on his knee. ‘Come on, give us a bit of fun,’ Dave said, ‘a bit more, the last bit.’ He tugged at her knickers. Nige had his hand in his trousers and the other man had unzipped himself and was rubbing his cock. Dave pushed her onto the sofa between the two men and then Nige pulled her on top of him. Gavin was next to him. She felt them pull off her knickers. She lashed out, kicking and scratching. It was this or she was nothing. She howled and bit whoever came near. Nige was swearing, mad with pain and anger: ‘Fucking bitch, you’ll pay for this.’ She screamed as he hit her on her face and breasts and forced himself inside her. The other man was holding her legs apart. She went on screaming and scratching and eventually the two men left her alone. ‘Can’t you shut the bitch up?’ Gavin shouted to Dave. ‘You need to learn to control your missus,’ Nige said. The water became cold but she sat there letting it run over her bare back until someone came and put a towel over her.

They told her he was dead and she neither believed nor disbelieved them. It didn’t matter. She was safe. And she wondered whether she had died because everything was different and she was different. She had to be dead. Alive, she had felt that force taking over her and then there were things she loved and things she hated, but now it was all the same. The next day she was in a holding cell when a man came to see her and said he was her lawyer. He was there to help her and he talked and talked. And that same question that the police had asked.

When she had returned from the refuge Dave had been nice, had bought stuff from Iceland and they had tea like a proper couple. He didn’t mind when she wanted to see EastEnders. He made fun of the story and laughed as he talked about the cleavage of one of the women but that was all right. And then one evening, as she was about to put burgers under the grill, there was a knock on the door and it was Gavin. He had broken down not far from their place and he wanted Dave to help him. She wanted to go with them – she didn’t care about missing EastEnders – but Dave said she should stay and watch the telly. He said he wouldn’t be long. But he was. She was asleep when he returned. She remembered him drunk, pushing himself into her.

‘But why didn’t you leave?’ He didn’t listen. Did he want her to repeat it?

The evenings after that followed the same pattern: Dave went out, usually with Gavin and came back drunk. Sometimes, when he was on an afternoon shift, Gavin came over with beer and they would drink before lunch. After Dave had turned up for work drunk for the second time, they sacked him. Of course they did; he was a driver for an off licence and they were strict about such things. Then he started complaining about her not working. She had tried hard, in shops and bars, but there was nothing or else the money was shit – it was better to be on the dole – and every day they argued. He said she should go back on the street but she didn’t want to do that any more. He hit her. Once when they quarrelled, the neighbours called the police but all the police did was to tell them to quieten down. That same evening he beat her up so badly that she lost consciousness.

The lawyer interrupted again with that same question: ‘Why didn’t you leave him?’

She thought for a long time but couldn’t think what to say. He was her man, it was proper; it wasn’t like Marvin giving money to her mother, it was real, they had dated for real. She wanted to stick with Dave. She could see it wasn’t easy for him with no money and no job. She had to help him out. That’s what couples did. And he was sorry when he hit her. Sometimes he said so.

‘Tits, give us the tits, come on.’ That was Nige’s voice. And then Gavin echoing him: ‘Tits, tits.’ She saw herself moving towards the door. But as she turned around, Dave was standing next to her. He took her in his arms and started to dance. It was nice. The men laughed and clapped. Then Dave kissed her and, for a moment, she thought he was thanking her and she would be free to go. She relaxed and let him turn her around, but he surprised her by unclasping her bra. Nige and the other man shouted: ‘Yes, tits, get her here.’

‘But you could have walked out? You chose not to,’ the lawyer said.

It was early afternoon when he came home with Gavin and Nige, carrying six-packs. He pushed her into the bedroom and closed the door: ‘Look, help me out. Nige has promised me a job.’ He spoke quietly, as if not wanting the others to hear. ‘A proper job.’ She didn’t believe him. He said: ‘Nige’s brother-in-law is opening a bar and needs a bouncer; I could fix things for him, be around. I have to keep him sweet.’ She asked what he wanted her to do. ‘A slow dance, and strip a bit . . . put them in good mood . . . that’s all.’ She stared at him. Three men drinking together and her stripping. That won’t be all. She didn’t do that any more.

‘Look, Tan, you don’t want to work.’

‘I do. I’ll get something. They promised me,’ she said.

‘Oh, they promised you,’ he mocked. ‘And you believed them.’ He turned away from her, lit a cigarette. ‘Have you forgotten Lilla?’ he shouted. ‘If I had a job, you could look after her, be a proper mum. I’m doing it for both of us.’ He sat on the bed, smoking, staring at her. She turned away, looked out of the window. The back yard was paved; that was where they kept the bins and Dave’s broken motorbike. She remembered when he tried to repair it and couldn’t and made it worse. That was the day when she was cheated and taken to that house. She had agreed to do a job in a car and then there were three men and they had raped her. They didn’t even pay and then Dave had hit her when she got home with no money. But it was the motorbike he was really angry about.

The question again, that question she had come to dread. He was thick, this lawyer.

‘Tan, come here, babe.’ He patted the bed next to him. She didn’t trust him, but she obeyed. ‘Come on, sit down.’ He put his arm around her, kissed her on the cheek and whispered into her ear. ‘It’s all right, if you don’t want to help. But . . . I need work . . . and it’s fucking hard to get anything. Nige has promised. I could start next week. That’s why I got the beer . . . to celebrate.’ He ran the back of his hand across her cheek. ‘You get my drift?’ He kissed her on the mouth.

‘Only stripping, no more?’

‘Yeah, of course.’

‘Only the shirt and skirt off. I can keep the bra and knickers on, yeah?’

‘Yeah, whatever.’ He stood up. She wanted to help him but she wasn’t going further. She’d do the dance and nothing else. Dave walked out. Through the closed door, she heard him talking to his friends and them laughing loudly.

‘Stripping for three drunk men? In your home? That’s mad. You were asking for it.’ This lawyer was doing her head in. Why was he so stupid? It was only a little strip, nothing else. Helping out.

A few minutes later, one of them shouted: ‘Show! When’s the show starting?’ She heard clapping and cheering. She wanted to tell Dave she was afraid they expected more than a strip. She heard him call: ‘Come on, Tan babe, we’re waiting.’ He wasn’t angry.

She opened the door and walked in. Dave had already moved the coffee table to the side and she stepped onto the rug in the middle of the room. Nige and Gavin were slumped on the sofa, beer cans in their hands. Dave sat in the armchair. The stereo was playing. She got on with it straightaway, thinking that the sooner she started, the sooner it would be over. It was important to please Dave by pleasing the men, but she was wary of getting them excited. They leered at her and she hated that. But it would be all over soon. She made herself think it was somebody else stripping, not her. Her mind was on that Great Yarmouth promenade, breeze in her hair, the ice-cream van playing a jingle. Marvin holding her hand. She unbuttoned her shirt slowly, but made sure that her eyes did not meet the men’s. With each button she unfastened, the men cheered. Then she took off her shoes, one by one, and the tights – she had she’d had no time to put on stockings – caressing her legs, as if trying to memorise their shape. She moved around, wriggling her hips, dancing barefoot in her skirt and bra. Nige tried to touch her but she managed to move away and he mumbled, ‘Teasing bitch.’ She went on dancing, but the other man shouted ‘Skirt off, skirt off’ and she began to tug at the zip, pulling it down and then a little bit up until it was done. She took off the skirt as slowly as she could and then carried on dancing. That was that. No more.

‘But even then you could have walked out.’ What was he saying?

Gavin pulled her knickers off and forced himself inside her, Nige doing the same from the back. She fought them, biting and scratching, that force inside her giving her strength, incredible strength. They were shouting ‘Shut the bitch up’ and running out, running away from her.

‘Your story’s no good. You consented. Why didn’t you leave?’ the lawyer asked.

Dave was furious, strode towards her, but she was quicker. She locked herself in the bathroom. And then it was quiet. She didn’t know how it happened but soon he was asleep. No, she is sure he wasn’t dead. She heard him snoring.

‘And then? He woke up and attacked you with a knife and you had to defend yourself,’ the lawyer said.

No, she was sure that he didn’t. He wouldn’t have done that. He was a fist man, not a knife man. Besides, he was too drunk and when he fell it was like he had passed out. In a second, he was fast asleep. But she was very angry with him. Mad at him. That mad like when you think I could kill that person, I could chop them up into tiny bits. But when she went to fetch the knife she wasn’t thinking that. She wasn’t thinking anything. She was only doing things. No, that’s not true. Her body was moving on its own. Her hand grabbed the knife and pushed it inside his chest and out.

The lawyer said that what she had just said didn’t sound right and that she was in trouble if she stuck to the story. He said that it didn’t happen like that. She was a confused young woman. What did he mean? He was going to write down what happened and she would sign it and then say the same to the police. Why was he asking her then if he knew what had happened? She said it loudly but he didn’t answer. Instead, he repeated that she had killed her violent boyfriend in self-defence. He wrote that down into his notebook. But was it Dave or was it Marvin who was dead, Marvin with his kind, lined face? The lawyer stared at her before repeating that it was Dave who had fetched the knife from a kitchen drawer and who had tried to stab her but she had fought him and killed him in self-defence. But what about Marvin? He was checking that she was warm. It was self-defence, she had to remember that. She didn’t care either way. She had told him what it was like – she knew, she watched it happen – but if he wanted to believe something else, it was none of her business. She was fine. That force had let go of her. She was safe.

A Woman With No Clothes On

WHEN EDOUARD INVITED me for a picnic, I suspected ulterior motives. I said yes, on condition he paints a picture based on my idea. I visualised a woman, with no clothes on, sharing a basket lunch with two men. The male figures would have to be fully clothed, the brown of their jackets blending with the surroundings. I wanted the woman to be the focus of the viewer’s gaze and it was essential that she returned that gaze as boldly as she could, transforming herself from an object to a subject in control. In my mind, I heard the men discussing some eternal truth, or a myth, perhaps suggested by a classical figure sketched in the background, enveloped in a gauzy garment, looking away from the scene. The woman with no clothes on, the naked woman, not a nude goddess, she would impart the idea of being here and now, a contemporary figure, almost falling out of the canvas, transcending the boundary between the world of the painting and the world of the Paris in 1860s. It was essential that she existed in the viewer’s present.

I knew Edouard was lonely – no wonder, he couldn’t tolerate fools; besides, he was often moody, troubled by something indefinable – and infatuated with me. I could ask for anything. He listened carefully to my idea and nodded, slowly and gently, as if he were transported to the picture that was emerging in his head.

I did not mind staying a night at the studio. He sketched tirelessly and said he would require me to return to pose when he was ready to work with oils.

The painting was turned down for the 1863 Salon. Exhibited at the Salon des Refusés, it became the talk of the town.

My idea became the talk of the town.

Mrs Dalloway

‘THE MARQUISE WENT out at five o’clock,’ Colin says but no one hears. His sentence, for ever his, all that story-telling and whodunnit has never interested her. A week before finals, when she had given him Barthes and had read out the sentence, he had said, ‘That’s how I shall begin.’ She didn’t ask what he meant; too busy studying with him every day and late into the night that week. Not that he had done much before; he didn’t mind getting a 2:1. She would have been distraught. ‘To A, who gave me the first sentence’ came a few months after graduation. ‘He was in love with you. And still is,’ Richard said later, years later. ‘Why else would he dedicate his first novel to you?’ Wrong as usual, poor Richard. How little he knows people.

‘The marquise went out at five. Why not the duchess? Why not at six?’ Emilie teased him, Emilie, the first woman who recognised the words. ‘The only woman I can marry, don’t you think, Anna?’ As if she had to approve Colin’s girlfriend. Did he mean it as a test, a test for his future wife or a provocation for her, for her who was already married? Emilie passed, being French, would have read Valéry. The reviewers didn’t get it, too obscure for them, even then, thirty years ago. Much worse these days, all hacks. Agents wouldn’t pick it up either. Commercial gatekeepers. Some, maybe. Order in stories, she had to explain to Richard. Yes, the marquise, not the duchess, and at five, definitely not at six. Order in stories but chance in life. Is that the beauty of it? Or not? The beauty of what? Stories or life?

‘The traffic’s hopeless,’ Marc says, justifying his lateness, or maybe to support Richard. Male solidarity. His usual party piece. ‘I was stuck on Hammersmith Bridge for three quarters of an hour . . .’ After twenty-odd years in London, he ought to be used to it. That candle, she needs to move it . . . yes, that’s better. As Richard says, what’s stopping him moving out? Not a steady job, that’s for sure. He could do his art anywhere, if only he bothered to pick up a brush. He claims the muse has left him. Nonsense. He’s lazy, that’s all there is to it. Why is he moving the candle back? She hates symmetry on the table. It’s her dinner party. If only he would take a breath between sentences, others might be able to join the conversation. He’s a friend, an old friend, and she loves him but she can’t allow him to dominate. Richard must be fed up too. No wonder he seems to have switched off. That’s what he does with her and then he has no idea, accuses her of not telling him. The others must be bored as well. Really, Marc’s monopolising her party. But is Richard subdued? Or tired after a long meeting. Could he be upset with her? She had been worried and she had lots to do; he should understand how she felt. It’s not as if she didn’t remind him in the morning and then he said he would be home earlier to help. She counted on him, of course, she did. All right, it wasn’t much fun for him either, enduring Bob’s blathering – there’s something about that man, he’s all over the place, with his baggy trousers, no one else wears anything like them, and the way he throws his legs about as if he had two left feet, a total mess, no wonder he can’t keep to the agenda – but then it’s not only him, all his staff, and that Myra, they all babble, their meetings go on for ever. Richard’s colleagues must be the most tedious academics in the country. They need somebody in control, but not Bob, that’s for sure. Bob who insists on chairing every meeting. But Richard could have rung. Maybe not. It might have been one of those situations where you think it’s about to end, it’s not worth ringing, but then it goes on and on and each time you think that’s it. Before you know it, hours have passed. It’s happened to her. Well, not quite hours but . . . It can make you tense. He would have been anxious.

‘Richard, you were stuck as well?’ Marc says.

‘No, no. It wasn’t the traffic.’ So dismissive of Marc’s question, so jittery.

‘What I’m saying, London’s too big . . .’ Will he go on about town planners next, like last time? Then Charles will feel obliged to start his own spiel. Let’s not have a repeat. Boring it was. Good for people to talk, but Marc’s obsessed. Richard is eating slowly, his eyes on the plate. If only she hadn’t said those things. She can’t help thinking the worst. Other people don’t immediately imagine tube bombs and heart attacks. She shouldn’t have been so harsh. But why didn’t he explain what kept him? The way he stood behind Marc, who was doing his round of greetings, histrionic, kissing and hugging her. Hello darling, you look fantastic. Carrying a board game, quite absurd. Always a big entrance, like an actor. Did he think this was a children’s do? She must have made a face . . . and why not? He ought to know she hates board games. Is there anything sillier? And there was Richard, stooped, clasping his hands in front of him, as if he were in short trousers waiting to be told off by the headmaster. Marc can intimidate people but Richard was on his own ground, and yet he had that air of self-consciousness, inexcusable in anyone above thirty. It didn’t help when Colin made the joke about two lads together somewhere secret and Marc winked at him, going along with it – now that was too much – and everyone laughed, but Richard looked down. Did he blush? No, he couldn’t have, she must have imagined it. She was irritated with him and marched off to the kitchen. He followed her and she told him that he had let her down. Not straightaway, no. She waited for him to explain why he was late. But not a word. That made it worse: he could see something was wrong and yet he didn’t offer an apology or explanation for his part. Why not, why couldn’t he have done that? She would have understood. But he was all silence. That was why she blew up. And then she was cold, she brushed him off. If only she could give him a hug now. When they are alone, he will complain to her about Colin’s sexist joke. Two of you lads being somewhere secret. As if she were responsible for her friends. Yes, sexist, but Colin’s like that. There he is: taking Christina’s hand and running his finger over her palm, tracing her lines, like a fortune-teller. The way he is looking into her eyes; but they’re old friends. And now he is whispering into her ear, what a performance. Poor Christina probably hasn’t had so much male attention in years; Charles always seems so distant. Must be nice being married to an architect, not having to think about the house, all the little decisions one has to make taken care of; she would have liked that, but Charles, Charles is too distant. She couldn’t cope with someone like him. It would make her feel unloved. Poor Christina. She isn’t taking her hand away. Yes, Colin’s a flirt but that doesn’t mean he has a roving eye. Richard’s silly to be jealous – for that’s what it is – of anyone who knew her before him, even friends. Colin likes people; he is friendly, chatty. Richard wouldn’t understand. Colin’s interested in others; what writer isn’t? But Emilie’s safe with him. Thirty years she has known him. She would vouch for him. And for Richard. Well, anyone would vouch for Richard.

Poor him. She won’t tell him what happened when Colin and Emilie arrived. He would only spin a story about Colin’s infidelities being the cause of the tension. Laughable how little he understands others. She could tell something wasn’t quite right. Emilie sounded hostile – as never before – when Colin ranted about mock Tudor houses. He hates them. So does she. Anyone with visual sense does. But the way Emilie frowned, quite unlike her. After more than ten years of marriage, she knows he’s an architect manqué. They must have had a disagreement earlier on. Couples have them. But she and Richard wouldn’t have behaved like that in front of others. It made her uncomfortable; no wonder she knocked over the bottle of wine. There’s still a small stain on the hem of her dress. What if it doesn’t come out? She will take it to the cleaners tomorrow. There is a specialist one, good with delicate materials, but no, they’re closed for a week, Seychelles or something like that, she heard. She would hate to see the dress ruined.

‘More salad?’

Emilie nods.

‘Shall I serve you, ma chérie?’ Marc says.

‘More wine?’ Richard should be topping up. Still looking down, unwilling to play the host. The lines around his eyes. Still at the meeting? Pity he can’t relax. Marc has been making up for him; that must come from living alone. But not for Sarah and it’s four years now. Almost. A cold November day. The sun shining. Was it Manet who said he wouldn’t allow funerals when the sun shone? Remembers that when she sees a funeral. And the image of Manet walking behind Delacroix’s coffin, at Père Lachaise, a warm, sunny day. Four years ago for Jocelyn, that brilliant light, the crisp air, the firm, frosty ground around the crematorium. The music was uplifting, You would expect a musician to pick up stuff like that. All planned as soon as the prognosis came. How does Sarah manage? No one since Jocelyn, four years now. She couldn’t bear to be unloved, not for that long, not for four months. No wonder Sarah’s gloomy.