Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Salt

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Serie: Salt Modern Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

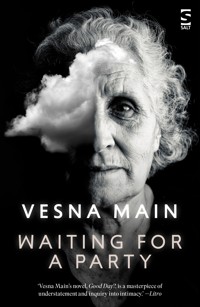

Claire Meadows is ninety-two, a retired piano teacher. She's baked a pistachio cake, as she has for seventy years, and is waiting to be collected for the 102nd birthday party of her old friend Martin, a detective novelist. As she waits, her thoughts meander through a lifetime of memories – marriage, widowhood, friendship, longing, and a sexual awakening that came shockingly late. With humour, ambiguity, and sharp insight, Claire reconsiders the man she married, the life she lived, and the strange, hard-won freedom that followed. What really happened the night her husband died? Did she remake her life, or simply reframe it? And is desire ever really behind us? By turns tender, frank, and subversively funny, Waiting for a Party is a quietly radical portrait of an older woman who refuses to disappear.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 311

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

VESNA MAIN

WAITING FOR A PARTY

For Milo and Phoebe,

hoping your world is better than the world we have now

CONTENTS

WAITING FOR A PARTY

1

Yes. She remembers the full moon, a large, luminescent paper collage against the sky, the fuliginous sky. That was the word he used, the word that stuck with her. She remembers the sharp lines of the full moon. Later, the image made her think of a picture drawn by a child, with the sky’s sootiness, threatening, noxious, replaced by dark navy blue, and a sprinkling of scintillating stars. She doesn’t remember there being stars on the night, but they entered her memory at some point and remained. That image, the transformed image of the view from the car parked to the side of Petersham Road, became associated with the man. But despite what the symbolism of the moon might suggest, she doesn’t remember him as cold and changeable. Perhaps he was but she could not tell at the time, nor could she tell that later but, if pushed, she would read the connection between him and the image that stood for him in her mind as implying art, meaning artfulness, artificiality, even affectedness, and play, as in lack of seriousness, unpredictability, randomness. Ultimately, he remained an enigma but, in her memory, art and play stand for him and for the experience they shared that night.

In the car, she was conscious of the silence but couldn’t think what to say to this man she hardly knew. At two o’clock on a Sunday morning, there was only sporadic traffic, but he had still driven slowly. The flattering thought, yes, she remembers thinking it was flattering that he might want to prolong the time spent in her company, yes, that excited her briefly but then it crossed her mind he was probably trying to avoid interest from the police. In the half an hour before they left, she saw him drink the best part of a bottle of wine and she could only imagine how much he had before. As they approached North Sheen, she realised that, within a minute or two, she would have to ask him to take a left and then, after a couple more turns, they would arrive at her street and the 2evening would be over. He would disappear from her life and she might never see him again. Never see him again. She felt the pain of anxiety at the thought.

When she looked back on that evening, she realised that what mattered most was the excitement she felt, the undefined desire, but not for the man himself, rather it was for the flutter in her chest that she remembered from her youth. She longed to resurrect the tremble in her inner being and perhaps the pain at the thought that she would never see this man again was nothing more than an unacknowledged longing to change her life. Not that she could have formulated it in so many words at the time. Such realisations always came later, sometimes too late. The years of her marriage and the years of her widowhood, up until that evening anyway, were calm. Her days passed in their uniformity, and she took whatever came her way as inevitable at her age. She took it for granted that she was invisible, as women over sixty are, with their grey hair and wrinkles, but that evening she felt, and she was surprised at the feeling, that she missed the flutter in her chest, the excitement at the possibility of being loved and loved in a way she craved, in a way that disturbs and unsettles. And with that realisation came self-reproach at being hopelessly romantic, sentimental even, in her mature age. Such a thought was unwarranted, she would say now, thirty years later, because she has realised that regardless of age, everyone needs love or, at least, everyone dreams of being loved. But when she considers that, the word yuck comes to mind and she admits to herself she would be ashamed to say the sentence about the need for love in front of anyone for fear of sounding as a heroine from a pulp fiction novel. No, she has never been a reader of such books and she mustn’t think like one.

But that night in the car, she wondered whether she should invite the man who had used the word fuliginous in for a coffee to thank him for the lift. What if he misunderstood and laughed at her audacity, spurned her presumption? How she agonized. At sixty-two, she should have been beyond such concerns. In fact, she 3felt as socially gauche as she did as an adolescent. So much for age removing inhibition, she thought. She was as shy as she had always been. The only difference was that she was better at covering it up.

She remembers thinking, and thinking with relief, that at least she didn’t have to worry about Martin; he was unlikely to be peering through his window on the off-chance there might be something interesting going on in front of her gate, two doors down the road. But what if he did catch a glimpse of her late-night visitor? What would he think of her?

What a ridiculous thought, she told herself, she remembers. More than ten years had passed since Bill died. She was entitled to a private life. It was none of Martin’s business. He could hardly object if she offered a coffee to the person giving her a lift. After all, the man, Jon – or was it John? – was making sure she was safe; he has driven well out of his way, and it would only be polite to ask him in. She couldn’t treat him like a taxi driver. Martin would agree, she remembers thinking. But, was it proper, she wondered, at this late hour, to encourage – encourage? The word made her pause, she remembers. Is that what it would be? – a man she had met only a few hours earlier? What would he take her for? Patricia would have known what to do; she was more than aufaitwith the etiquette of dealing with strangers in the early hours of the morning. But Patricia was in Scotland visiting her aged parent and, in any case, she couldn’t be ringing her well past midnight to ask for advice. The car was about to turn into the street leading to hers and, in a few minutes, she will have to direct him where to stop. And when he did, should she wait for him to speak? She had already changed her mind five times. But what if he stopped the car but left the engine running as if expecting her to get out without any further ado? Or, even worse – would that be worse? – if he parked and turned the engine off? Would she have to invite him in then? Should she be affronted by his presumption? But once the seed had been planted in her mind, she could hardly remain silent. If he didn’t, she would have to act. She remembers the confusion she felt at the thought: What 4seed? Excitement? Expectation? Seduction? The seed of seduction? Get real, Claire, what are you thinking about? You are sixty-two. Sixty-two but thinking like a teenager, and a silly one at that.

That party was Millie’s idea. ‘You must start socialising; it would do you good to meet new people. It’s unhealthy to be alone all the time.’ She could hear Millie’s voice. But she wasn’t alone. She saw Martin every day. Millie read her thoughts: ‘Martin doesn’t count. He’s an odd sod, an old misanthrope. You will grow strange like him.’

Why shouldn’t she carry on in the same way, if she was happy with her life? Besides, Martin was a most caring friend. But she knew better than to argue with Millie. It was going to be a long night, what with the concert before. She planned to make her excuses after the concert, say she had a headache and make her way home, but Millie and Max joined forces; they wouldn’t hear of it.

‘I can see you’re getting cold feet. Come on, Claire, make an effort. You’re too young to wait for death, shuffling around in your slippers. A party, that’s what you need,’ Millie said.

Typical Millie, she always knew what others needed. And unfair to boot. She had a busy life. She worked. She took regular walks with Martin and Poirot. She never missed a major exhibition, she saw lots of theatre, films. But there was no point arguing with Millie. Okay, it was true that she had dropped her reading group after more than three years but only because it was dominated by a boring man who imposed his choice of novels about grumpy old men fearing death, the characters forever banging on about prostate problems. And, she had attended two courses on French patisserie. She was hardly leading the life of a hermit, she remembers thinking. But to whom was she trying to justify her life? The truth was that she didn’t need much persuading to accompany Millie and Max to the party. It was all a show, a show for the part of herself that was too shy to accept that sixty-two didn’t mean the end of life. Why did she buy a new dress if she had no intention of going to the party? Not for the concert. She had enough clothes for such occasions. But this time, because of what was to follow the concert, 5she wanted to feel special, she wanted to feel confident, she wanted to feel different, she wanted to leave behind the years of marriage and the years of widowhood.

Sitting in the car, next to the man, whose profile – a strong, slightly hooked nose and a prominent chin – she had been admiring from the passenger seat for the past half hour, she was beginning to wonder whether Millie had a point about the importance of meeting other people. She remembers she sensed something mysterious about the man, something that intrigued her, something that made him unlike anyone else she had ever known. And then that same thought came to her mind that she might never see him again and she was gripped by a feeling of loss and she knew she needed to act and act urgently, say something, prolong the moment. She remembers she thought he liked her, at least enough to flirt. But what if he was one of those men who flirted with any woman and was only being kind in offering her a lift? Either way, she remembers, she couldn’t trust her judgement.

She remembers that as soon as they had arrived, Millie and Max disappeared, and she was alone in a crowded room where she didn’t know anyone. A few nervous approaches resulted in one-minute, stilted exchanges before the other person excused themselves and rushed off to whoever they ‘had to talk to’. She felt lost. She hated the idea that she was lost because being lost was part of her previous life. The concert had been brilliant but the uncomfortable atmosphere at the party was ruining the memory of the elation she had felt watching the pianist’s fingers in their dance across the keyboard. Why had she let herself be persuaded to go to the party? She didn’t need anything else to make her evening. It was good to share a drink with Millie and Max during the interval but afterwards she felt like going home and curling up with a book. She remembers thinking that she should have been more assertive. She wanted to ring somebody, both to cheer herself up and to give the impression to everyone else in that crowded room that she was alone because she was busy making a call rather than because no one noticed her 6but then she realised that she had left her mobile in her jacket in the hall and couldn’t face fighting her way through the chattering crowd to fetch it. She remembers, it was one of the first mobiles that were around. Bill had bought it for her after his heart attack so that he could reach her if needed. They were large, heavy objects, like bricks, bricks with a pair of aerials that needed to be extended for use. She probably wouldn’t have been able to squeeze through the crowd anyway; to most of those people she was invisible, and they were unlikely to make way to allow her to pass.

Glass in hand, she wandered through the French doors into a garden lit by lanterns hidden in the bushes. She remembers that the air was saturated by the scent of trees in blossom but her urban nose failed the identification test. She was wearing high heels and after leaving the patio, she wobbled along the narrow-cobbled path that wound its way down the garden, as far as a stream that cascaded over a small waterfall. She sat down on a wooden bench, barely a yard from the edge of the stream; the party was a distant murmur, lost in the splashing of the water against the stones. She closed her eyes. It was relaxing; the water music allowed her to dream. She was somewhere else, not trapped by a group of loud people she didn’t know. She felt light-headed; the image of the pianist’s fingers made her dizzy with envy. If only she still had the ambition of youth, and the drive to practice, she remembers thinking. She was regretting growing old. Growing old! She wasn’t growing old, she was old, she told herself. Old without realising that mysterious something, that something that is born from the joy and the pain of the urge to create, that something that makes you feel alive. How silly she was to think she was old, she thinks now. To think it was too late. But it is too late now.

She remembers she didn’t hear anyone approach and had no idea how long he had been standing behind her. A voice said, ‘would you like another drink?’ and that, she remembers, brought her back from her reverie but it took her a second or two to realise that he 7was addressing her. She turned around and, against the lights from the house, she made out a gangly silhouette. Had he followed her into the garden, she wondered, she remembers.

‘Are you expecting someone?’ he asked.

‘No,’ she said quickly, having no idea what he meant. ‘Why would I expect anyone?’ Immediately, she regretted the hostile tone.

‘A tryst in a dark corner of the garden.’ His voice was serious, despite the irony. ‘I saw you walk out with determination. I was sure you had an assignation, a secret assignation in the bushes.’

She remembers wondering whether he was being serious. ‘I didn’t realise it was that kind of party,’ she said smiling, pleased with herself for being able to sound casual and project a level of self-confidence, even though a tryst was the last thing on her mind.

‘Every party is that kind of party if you want it to be,’ he said and waited for her to respond. When she didn’t, he changed tack:

‘Would you like a top up? Your glass is empty,’ he said.

She declined: she had drunk too much already. He teased her for being puritanical. He wondered whether she wasn’t enjoying the party and she struggled to respond in case he was the host or a close friend. He sat down next to her. He held a bottle in one hand and a glass in the other. He steadied the bottle on the ground between his feet.

‘I don’t blame you. This lot are terrible bores. They all have their freedom passes but their parties are no different from what they were forty years ago. Only the décor has changed, and they drink from expensive glasses instead of plastic cups. The conversation is as trivial and pompous as when they were students. They’ll be putting on the Rolling Stones in a minute.’

He had a lot of baggage. She remembers asking him what he would prefer to talk about?

‘I don’t know. Things that matter. But not whose child has bagged which job and what they are buying their grandchildren for their next birthday.’ 8

‘You don’t have any grandchildren?’

‘God, no! You have to have children before you can have grandchildren and I’ve managed to avoid that particular predicament. I was a wise young man, even if I’ve turned into a foolish old one.’ She remembers she wondered whether he was a genuine cynic or whether this was his party piece, something to wheel out with strangers.

She laughed.

‘But you do disagree, don’t you? You think grandchildren are sweet, or cute; isn’t that the word they use?’ Too shy to tell him what she thought, she shrugged. She remembered that moment later and thought how she had always played by the rules of small talk, always agreed in that anodyne, unconfrontational manner, always said what others wanted her to say. Bill had expected that from her.

‘I bet you have a few. Cutie-cutie little ones,’ he sneered. ‘Here comes granny,’ he chirped.

‘No, I don’t have any grandchildren.’

‘One on the way then.’ She couldn’t see his face, but the mocking tone was clear.

‘No. I don’t have any children either.’ She remembers thinking that it was the first time in her life that she could say it without feeling pain. And she liked him for that.

‘To a fellow soul, a sensible soul,’ he said and raised his glass.

She remembers every word they said. She remembers the sound of the water cascading against the stone feature. There was chill in the air and she wondered if Millie and Max were ready to leave. She turned towards the man and said she was going to get her jacket and look for the friends who had brought her. It was well past one o’clock. The man asked who her friends were and when she described them, he told her he had seen them leave half an hour earlier. He referred to them as crusty people. She was going to call a taxi but he said he too was leaving and would take her. She remembers saying that she didn’t want to impose. Richmond was hardly on his way to Hampstead. He did not so much insist as assume they would leave together. In a matter-of-fact voice he said that it would be good to 9drive through West London at this time of night. She wondered what he meant but didn’t ask.

‘We’re almost there,’ she said.

She directed him to turn left but the road was blocked. They took the diversion and found themselves on Petersham Road.

‘I used to love the view from here,’ he said, his head gesturing towards the river bathed in moonshine. ‘The way the river loops, just like a Constable painting.’

He seemed almost dreamy but then checked himself. He turned towards her and said with more emphasis than was needed: ‘Not that I’m a fan of Constable.’

The real Constable view was from up the hill but before she could point that out to him, he added: ‘And when I was young, they had cows grazing in that field.’

They still did but she couldn’t see any at that time of the night. She said that she had often seen cows sitting down in the meadow by the river, yes, she distinctly remembers using the word meadow, and added that someone had told her that cows sitting down was a sign of rain on the way. She didn’t know why she said that since she could see no cows, sitting or standing, except that something about the manner of the man she had known for barely an hour, something about the way he talked in that casual, over-confident way that both impressed and frightened her, made her utter words without considering them beforehand. She remembers thinking that he had an air of smugness. The way he took it for granted that she would accept his offer of a lift made her timid and self-conscious. To compensate, she talked too much, she talked for the sake of talking, for the sake of breaking the silence, and there was little chance she might say anything clever or remotely impressive. She remembers thinking that a woman of her age should not have to resort to trivial babble to cover up whatever it was, her shyness, her nervousness, or her lack of recent experience of the social discourse required when she found herself alone with the man she has met at a party, a man whom she might find intriguing, even if she couldn’t tell in what 10way, a man not necessarily attractive in himself, but attractive as a proposition, as a novelty in her quiet, uneventful life. Those were the possible reasons why she mentioned the cows, and as soon as she did, she remembers that she knew her words would sound silly. Unlike many other people she can think of, people who would, in the presence of a stranger be gentle and kind, gentle and kind for the sake of kindness, gentle and kind for the sake of the weak, the underdog, the people who would attribute the silliness of the words of the other in their company to the potential awkwardness of the situation and say something about the idea being interesting even if it was an urban myth – or was it meant to be an old wife’s tale? – and raise the question of how such beliefs came into existence, and the entire conversation would be forgotten with no consequence for anyone’s confidence, with no judgements passed or implied by the interlocutor and no one would be made to feel uncomfortable, she knew immediately that wouldn’t be the case with this man. He seemed to be well-versed in scoring points and, like a dog smelling fear, finding someone who was too weak to oppose him only encouraged him. She might have given the impression that she was in awe of him – no, she wasn’t, she remembers she wasn’t – and when she thought about it later, she knew that it was he who had been shy and lacking in self-assurance and that his over-confidence was bluster, acting, and poor acting at that, because he was not good at covering his shyness, despite being close to, or perhaps over, seventy years of age. But that was not something she thought at the time when, in accordance with his patronising manner, he smiled, and it was a supercilious smile, a smile that said yes, you are the kind of woman, yes, woman, he wouldn’t have said a person, who believes in such things and I don’t think I would have expected anything different from you. She doesn’t remember the exact words that accompanied his smile, but their effect was to make her feel even sillier and it further undermined her confidence. She was ashamed of making herself appear credulous, or would it have even been superstitious? But she could have still saved herself had she had the presence of 11mind. She could have thought of something to say to make him pause and consider her words, even respond to them, rather than dismiss them and dismiss them in such a contemptible manner. She could have said something about the way irrational, old beliefs survive and how sometimes people use them to create a sense of certainty in an uncertain world. But she didn’t have the presence of mind. Despite her feelings of inadequacy and shame, she carried on sitting next to this man in his car parked off the road leading west from Richmond Park at two o’clock on a Sunday morning without having the slightest inclination to leave his company or reach her home as quickly as possible, as you might expect the recipient of that supercilious smile to do. Moreover, she remembers she experienced a slight feeling of panic that she would soon be alone and most likely never see this man again, this man who was full of himself and who made her feel inadequate.

For a long time after that early Sunday morning she thought about her reaction to the situation at that point and concluded that, even though ten years had passed since the death of her husband, at sixty-two she was still thinking of herself as a child, a person watched over by a responsible adult. She had married in her early twenties, a man who had been more than two decades older than her and who spontaneously assumed the role of a parent to her, and not only because she was an orphan at twenty but also because her behaviour, the paralysis that she felt at the time, allowed, and possibly encouraged, involuntarily encouraged, Bill to act in loco parentis. After more than thirty years of marriage, she had become used to being looked after, used to having decisions made on her behalf and therefore, even without her husband being around, she remained passive and, perhaps even more importantly, she saw herself as passive. She remembers that was the image she had of herself, even though, once she was on her own, she managed the practical aspects of her life perfectly well, she made all the required decisions without hesitation or delay, as well as conducted her financial affairs, all those tasks that she used to think were exclusively the domain of 12an adult, her husband. Despite her ability to manage perfectly well on her own, she continued to think of herself as someone who needs looking after, someone who is passive, who doesn’t make trouble, someone who lets events take their course. Throughout her adult life, Bill looked after her. He looked after her and she was grateful for that. That’s what Bill thought. That’s what everyone thought. That’s what she thought. One day Patricia said she was like an object, carried on by the force of a stream that was Bill. An object unconscious of the current, not so much indifferent to where it was to end, but accepting whatever happened, slowly disintegrating until it disappeared. She dismissed those unkind words. But later, many years after his death, she looked back on her marriage and one day it occurred to her that the woman married to Bill had nothing to do with her. It was someone who had been impersonating a wife, the wife Bill needed.

The sense of passivity, or more correctly, the image of being an object with no will of her own became an inalienable part of the way she saw herself. She remembers that passivity and detachment became her default attitude to everything around her. In the car on the road leading west from Richmond Park, she was confused and scared, yes, scared too, but she waited. She waited because it was not in her nature to act. She waited for events to take their course. That was her default attitude. But she also remembers willing something to happen, something unexpected. She was anxious too, not because she thought the man next to her was a serial murderer, but she was apprehensive of making a fool of herself and, in a bizarre way, it was that apprehension, that entirely to be expected apprehension, which was exciting. When she looked back, she wondered if it was the challenge presented by a situation she had never experienced that was exciting and that, despite her fear, allowed her to enjoy the moment, an enjoyment of a kind that was new for her. Such contradictory feelings, feelings she wasn’t aware of at the time, or rather, didn’t have a chance to consider and acknowledge, brought about a sense of anticipation that something unusual was about to happen and the 13anticipation, she remembers, gripped her in a way that assuaged the shame of her silliness. She remembers that her instinct prevented her from confronting the man about his unkindness because she thought her intervention might have inhibited further development, which would have put an end to the situation, if he decided, as a result of her challenge, to drop her at home with a simple, curt good night. She sensed instinctively that he was the kind of man who needed a weak woman so that he could act. And she wanted him to act. Had she confronted him for being unkind, she might never have known what would have happened had she not intervened. But, of course, she was not conscious of such calculations. She felt excited about the what next. For she sensed that something was to happen. While it was not a situation of her choosing, there was a buzz around it, and the last thing she wanted was to put a stop to it. Thinking back, she couldn’t even say that she didn’t like the man as such thoughts didn’t cross her mind. Had she had time to think about the situation, she might have realised that her amusement, if not bewilderment, was born from a sense, no matter how vague, that at her age, something unexpected, something she has never experienced, was about to happen and that she wanted it to.

She remembers he asked her whether she would like to take a walk and without waiting for her answer, he parked the car. They sat in silence and stared ahead. She racked her brain for something to say but, in front of him everything that came into her head seemed banal. The cows sitting down presaging rain. She wondered what was on his mind. After a few minutes, without saying a word, he turned towards her, his face expressionless. As if in slow motion, he placed his hand on her chest, just below the neckline. She remembers his cold, bony hand on her skin. The hand remained still, as if he was trying to assess whether she minded. Her heartbeat accelerated. She remembers that a lump appeared in her throat. He stroked her breasts through the dress, moving his hand very gently, barely touching the material. Her whole body tingled. She took a deep breath. Slowly, his hand moved underneath the neckline of the dress, slipped under 14her bra and cupped each breast in turn. She remembers that he held them as if measuring their weight. A moan escaped from her mouth.

Later, she remembers, she considered his audacity and wondered if she had unwittingly transmitted signals of her availability during the journey but she dismissed the thought. He was a man whose confidence was entirely internal, fed by his inflated sense of self-importance, bordering on arrogance. At the time, she was startled by the speed at which things happened, impressed by his dexterity in moving over the gear box with one elegant swoop of his body, and almost instantly releasing the handle that allowed him to push her seat back and create space for him to sit astride her, face to face. She remembers that he was considerate enough to keep his weight on his legs, which must have been quite a feat for someone of his age.

She remembers his kisses as deep and overpowering, like warm waves entering her mouth; they left her short of breath, but she didn’t want them to stop. Not that he was giving any signs of tiring. She remembers thinking that he kissed her as if he had been starved of affection, as if she was the most desirable woman in the world. Then he was quick with the zip on the back of her dress and expert at releasing the hook of her bra, but he needed help removing her tights. She thought quickly: it was enough to bare one leg and slip the knickers over. She came almost as soon as he entered her, but his fingers continued sliding against her clitoris. She threw her head back, drunk with the excitement. She enveloped him tightly, her fingers sliding down his back. He moved inside her until she felt his body stiffen and he was spent. She remembers the feeling of joy. Bliss. She remembers. Like never before. She remembers.

As soon as she was breathing more steadily, she became aware of her surroundings. Had anyone been watching them? A policeman perhaps; they could be arrested for gross indecency. She remembers a headline flashed in front of her eyes: ageing piano teacher in car sex frolic. How bizarre to think that. But that was her in those days. She shouldn’t have cared. The ageing piano teacher had just experienced her first orgasm with a man. 15

He didn’t seem to be in any hurry to move and she remembers feeling grateful to him for holding her gently in his arms like no one had held her for many years. He planted kisses on her forehead.

‘Your eyes are so blue, like a child’s,’ he said.

Yes, she thought. Yes.

She remembers the morning after. She didn’t wake up until the afternoon, the first time it had happened in many years, possibly the first time since her early twenties, and her first thought was: what would Bill have said? ‘My dear, little Claire, what have you done? My dear, little Claire is again my lost, little girl.’ Bill liked a quiet life and that meant routine, regularity. Anything unexpected, out of the ordinary, would upset the quietness of his life and he wasn’t prepared to tolerate it. She went along with him most of the time without complaint, but even after he was dead, she stuck to the routine, sometimes consciously, sometimes unconsciously. She remembers thinking that it saved her, the routine saved her, she used to repeat it to herself when she didn’t feel like doing something but believed it was necessary for her to keep going in the same way. But the morning after, she awoke past midday and that was out of the ordinary. That was a break with the routine. She didn’t realise it at the time, but it was the first day of her new life, the new Claire. She did think what Bill would have said, yes, she remembers, how absurd that the first thing on her mind was what Bill would have thought of his dear, little Claire. But then, the anxiety she used to experience when she worried what he would say disappeared at a stroke and she laughed, yes, she laughed, she laughed loudly. She was Claire, but she wasn’t anyone’s Claire, let alone their dear, little Claire. She was Claire, a grown-up woman, for the first time at the age of sixty-two she was grown-up, her own woman with her own desires. She didn’t have to answer to anyone but herself. She remembers she wasn’t shocked at waking up so late and lazing about 16in bed. She remembers that what did surprise her was her nonchalant attitude that it was okay to do things differently, that it was fine to break away from the routine of her life, from the forty-year order. She was relaxed, and she remembers she stayed in bed, luxuriating in one of those moods where time stops and the mind dances with memories, memories resurfacing briefly, only to disappear and give way to other images, other smells, other voices from the past.

And today, it is not the morning after, hah, there are unlikely to be any more mornings after, but memories surge, fighting for attention, placing themselves one on top of the other, like hands in a child’s game. She wants to hold onto them and re-live the palimpsest that is her life and she wants to remember everything. Memory is all. Memory is her life now. She must remember to call Zach and remind him to buy a box of macarons for Martin. But no, she knows there is no need. Zach would have remembered. The caring Zach. He always remembers everything she asks him. That’s kind, that’s what being caring means, not having to be reminded to do something for and by those one cares about. Zach has been buying the same birthday present for Martin for the past thirty years. It would be silly of her to remind him.

How interesting that Martin only likes green macarons, pistachio flavour and yet she has never told him about the green macarons in the Paris of her youth. Perhaps that’s what they have in common, she and Martin. A special affinity for pistachio macarons. Perhaps he could have been her friend even if she had not married Bill. But it was Nick and his gift boxes from ‘Le Macaron Rose’ that developed Martin’s taste. She will mention it to Gabriel. Is there a story in that? A story of coincidence. But coincidence for her, not for Martin, because he doesn’t know about her green macarons in Paris. Isn’t life full of coincidences? Sometimes it takes a long life, as long as hers, to spot them. One needs the perspective of time to see a pattern. But in the end, what does it mean? It’s amusing. Nothing else.

She remembers once meeting a woman who told her that her 17