11,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

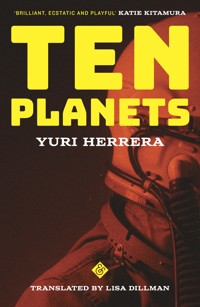

- Herausgeber: And Other Stories

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

The characters that populate Yuri Herrera's first collection of stories inhabit imagined futures that reveal the strangeness and instability of the present. Drawing on science fiction, noir, and the philosophical parables of Borges's Fictions and Calvino's Cosmicomics, these very short stories signal a new dimension in the work of this significant writer.In Ten Planets, objects can be sentient and might rebel against the unhappy human family to which they are attached. A detective of sorts finds clues to buried secrets by studying the noses of his clients, which he insists are covert maps. A meagre bacterium in a human intestine gains consciousness when a psychotropic drug is ingested. Monsters and aliens abound, but in the fiction of Herrera, knowing who is the monster and who the alien is a tricky proposition.This collection of stories, with a breadth that ranges from philosophical flights of fancy to the gritty detective story, leaves us with a sense of awe at our world and the worlds beyond our ken, while Herrera continues to develop his exploration of the mutability of borders, the wounds and legacy of colonial violence, and a deep love of storytelling in all its forms.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 136

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

Bookseller Praise forTEN PLANETS

‘Strange, surreal, and brimming with playfulness.’

John Bittles, No Alibis Bookstore

‘Leave the world with everything you think you know behind and depart on a journey of exploring new possibilities, new realities and questioning what you take to be true. Absolutely mesmerising!’

Lea Deppe, Bookhaus

‘With Yuri Herrera’s Ten Planets fiction has finally caught up with the 21st century. The short stories inside are quantum pieces existing in two places at once. Read altogether they have a cumulative effect that envelops the reader with a warm sense of the subliminal and supranatural yet never leaving the mundane behind. This is such lyrical, enchanting, inventive prose from a formidable imagination at work.’

Ray Mattinson, Blackwell’s, Oxford

‘Whether plumbing the darker depths of our psyche, or soaring into ecstatic expanses of hope, these small, surreal stories – glittering with invention and shards of charming, unnerving naivety – each have the undeniable gravity of a collapsing star. You’ll find your mind orbiting them long into the night.’

Joe Hedinger, The Book Hive

‘An excellent and intriguing book. The ideas and variety are such that at no point does it run out of steam or originality.’

Keith Cowans, The Book Vault

This edition published in 2023 by And Other StoriesSheffield – London – New Yorkwww.andotherstories.org

Originally published in Spanish as Diez planetas. This English edition is published by arrangement with Editorial Periférica de Libros S.L.U., c/o MB Agencia Literaria, S.L.

Diez planetas copyright © 2019 Yuri HerreraTranslation copyright © 2023 Lisa DillmanTranslator’s note © 2023 Lisa Dillman

“The Science of Extinction” appeared in the Iron Lattice.“The Obituarist” appeared in Washington Square Review.“House Taken Over” appeared in Words Without Borders.“The Objects” [#1] appeared in Epoch.“The Objects” [#2] appeared in World Literature Today.“Flat Map” appeared in ZYZZYVA.“The Monsters’ Art” appeared in Southwest Review.“Obverse” appeared in ZYZZYVA.“Appendix 15, Number 2: The Exploration of Agent Probii” appeared in Boston Review.

All rights reserved. The rights of Yuri Herrera to be identified as author of this work and of Lisa Dillman to be identified as the translator of this work have been asserted.

ISBN: 9781913505608eBook ISBN: 9781913505615

Proofreader: Sarah Terry; cover design: Carlos Esparza; cover photograph: Levi Stute; typesetting and eBook by Tetragon, London.

And Other Stories gratefully acknowledge that our work is supported using public funding by Arts Council England.

Contents

The Science of Extinction Whole Entero The Obituarist The Cosmonaut House Taken Over Consolidation of Spirits The Objects The Objects Flat Map The Earthling The Monsters’ Art Obverse Inventory of Human Diversity Zorg, Author of the Quixote The Other Theory The Conspirators Appendix 15, Number 2: The Exploration of Agent Probii Living Muscle The Last Ones Warning Translator’s NoteThe Science of Extinction

When the man realized he’d soon be lost, he took out a small yellow card, wrote four words, and placed it on the sill of the window he looked out every day upon waking.

He no longer remembered the names of the people he’d once lived with. A wife, a daughter, a son, someone else. Cuddles, squabbles, drinks, doors, greetings. Then slices of greetings, doors, drinks, squabbles, cuddles. Slices ever thinner. At first he’d tried to boost his concentration by counting from a hundred to zero several times a day, but now he had started losing his way around seventy, and all the numbers began to resemble whimsical versions of zero.

He no longer recalled his date of birth. Or the city where he was born. Or his parents. Had he had parents? There was no one left to tell him this either.

He knew that things were going on inside his body, that he needed medication, but he would happen upon it only by accident, walking into the kitchen and seeing a bag of rice, or lying down and discovering the pills by his bed. For he’d also forgotten what to call that chill in his stomach, that defeat in his bones.

There were moments of wordless euphoria, when he’d marvel at his lack of fear of a noise or an object he could no longer name. And he decided—and could recall this decision though not the exact words with which he’d made it—that he was no longer going to lament. Perhaps it wasn’t a decision but a strategy for survival or a new aptitude.

Sometimes he would see something, an object with four legs and a flat surface, and call it cup. And he saw that this was good. Sometimes he noticed something fluttering in the wind and it didn’t occur to him to call it anything in any lasting way, but he saw that this too was good.

The increasingly depopulated world rewilding on the other side of the window was full of other things he couldn’t recall having paid attention to. Horizons, dust, corners. And the silences.

The too-many silences.

The reason he didn’t get lost was because of the silences. At times he yearned to walk and walk with no destination, but the silences, each so distinct, came one after another: an impenetrable jungle of silences overwhelmed him, and then he’d go back inside.

One day a disturbance appeared before him: an undulation of swirling sounds, colors, velocities. He was transfixed for quite some time (which might have been a second).

Then he decided to address it. In a stammer of random syllables that in his head formed a crystal clear sentence, he said:

“I found a message that someone left us on a card. It says, ‘Everyone is going away.’”

He waited a brief eternity for the reply, then the little swirl spun again and vanished.

Whole Entero

The vespertine coliform existed, complexly, in the summer of 1999, in the region of Norfolk, England; specifically, in the town of Sheringham; to be still more exact, in the small intestine of one Roger Wolfeston, former manufacturer of fake documents, who’d had a bit of a boon. This blunder of nature resulted from the unexpectedly swift evolution of a bacterium of the enterobacterial order—a Citrobacter, since we’ve unloosed the illusion of precision—entering into contact with a lysergic acid in the microvilli of Wolfeston’s large intestine. The improbable chemical reaction triggered by the prolonged exposure of the saprophytic flora to the acid—which Mr. Wolfeston had picked up on his last trip to London and which did not yield the expected outcome—led the aforementioned bacteria to undergo unforeseen changes in the adolescence of its existence, though none that made it lethal or diminished its fermentative qualities. It’s just that the bacteria, miraculously, gained consciousness.

The vespertine coliform made a leap from eternal wintering to the perception of the immeasurable: a wordless splendor. The vertigo of fluids, vestiges of earlier ebullience, angles and surfaces of other bacteria, all of it pointed to her place as the center of the universe; she was the crossroads through which meaning was given to what we approximate with names like temperature, light, and time.

The universe’s distinction led her to name it by gradations of consciousness: the great intensity with which she perceived a crest or the emptiness of certain times of day became the thing’s name. She learned first to wait, then to yearn, and finally to imagine. And with the realization that what was was not what was but what could be, she began to erect for herself a place in the world. The understanding that ensued from that moment is what has come to be called the placid eve of the coliform: the period in which she made unbridled plans to bust out of her field of motility, traverse uncharted zones of the intestine, and leave a trace of her scourge at every point.

The vespertine coliform managed to sophisticate her emotions to such a degree that, prior to the Apocalypse, she succeeded in knowing existential anguish. She surrendered herself to the feeling of having lost something she’d never had, on discovering that the garden that housed her was beginning, inexorably, to decay. Why? Why must everything come to an end? Why had it begun to begin with? It would have done no good for anyone to inform her that there was a primary host and that he, Roger Wolfeston, broker of false papers, was dying of abstinence in the rehabilitation center to which he’d been sentenced by the law; no good even if it were communicable, for the scale of those events was so inconceivable (the existence of an organism so enormous and labyrinthine that it could host millions like her!) that the only way of relating it to her reality was by means of a fiction. For a moment she intuited this solution—religion—but by that point ennui and loneliness had descended.

She, the vespertine coliform, was one light of awareness among billions, the vastest population on an earth she had never managed to conceive, but the feeling of emptiness so overwhelmed her that, on glimpsing the divine solution, she discarded it instantly, convinced that if she could articulate something so immense, if there existed an instrument—words—with which to formulate it, then that thing was impossible; no, the grandiose and definitive could never be defined by the brief and simple and elementary. And long before Roger Wolfeston could relieve himself with a needle, relapse, and die, the vespertine coliform fell ill from sadness and, almost without realizing, was extinguished forever.

The Obituarist

On the way to the scene of death, the obituarist groused about fucking invisibility: Fucking invisibility; as if I didn’t know that this empty street, just like every empty street in every other city, is teeming with people.

The only ones who could be seen were the ones whose jobs required public visibility: delivery people, plumbers, painters, etcetera. They got badges, and when they put them on, became what they had to be and only what they had to be: delivery person, plumber, painter, etcetera, each covered by a neon silhouette. The rest wandered about unseen, protected by a buffer that blocked images, sounds, odors, keeping their bodies at a distance. Which meant that, walking down a deserted street, you’d bump into soft lumps that knocked you gently from side to side. Only in the heaviest congestion could people’s contours be seen and thus avoided, but there was never any need to see faces or expressions, feel bones or fat. Ever. The buffer served as a laissez-passer, allowing travel, and owners could take them off only indoors.

Yeah, big deal, the obituarist muttered, as he did each day: he could still sense them at that very moment. Their irritated presence, their contained rage. He might be able to stop seeing others but he couldn’t stop sensing their essence. Sooner or later even children learn that hiding your eyes doesn’t actually make things disappear. I can sense them right now, he repeated, making his way through the subdued reproach of those standing aside to let him pass.

He reached the building, saw the elevator doors open, and tried to get on but bounced gently off the people inside. He walked up three flights. There were already two badges at the scene of death. Certifiers. They certified the dead’s death, and he recounted the living’s life. Though the government possessed every piece of electronic communication anyone had ever sent in their life, the obituarist didn’t use them to tell their story, basing it instead on what the living had left behind. His obituaries were wildly successful. The public devoured them, not only to learn what a person had done without having had to put up with them while they were alive, but because many had high hopes that accumulating certain things would enable them to manipulate obituarists into telling better stories about them.

“Lotta people out today?” asked one of the badges, neon pulsating with each word.

“Same as ever,” replied the obituarist. “But the most important person in the room ain’t complaining.”

The obituarist didn’t like people criticizing his work. He prided himself on being punctual. Though it might seem his profession was the one least requiring haste, he knew how important it was to get to a story before its parts began to dissolve.

The certifier who’d spoken pulsed softly in silence. The other said:

“Nothing new. Guy had a functioning heart one second and a nonfunctioning heart a second later.”

The second certifier was, most likely, a woman.

He observed the body. It looked tired, even in death. The kind of tiredness that was no longer common: hands wrinkled, skin weathered, a rictus of severe resignation. While he studied the body, the certifiers put away their instruments and were already on their way out when the obituarist said:

“Don’t go.”

He thought he felt something.

“Is there someone else I need to see?” he asked.

The certifiers pulsed doubtfully, containing more than emitting their neon. They didn’t understand what he meant.

“Is it just the two of you?” he went on. “No one else came with you?”

“Two, as it should be,” said the one who’d spoken first.

“Wait for me at the door.”

The certifiers obeyed, no clear emotion discernible from their silhouettes.

He began searching through what the dead man had left behind. Kitchen utensils. Few. Generic. Indicating no interest in complicated dishes. Furniture. An armchair, a table, a chair, a bed, a dresser. Generic. Made to meet basic needs. And clothes. Lots of clothes. Odd. People didn’t tend to accumulate clothes now that buffers were mandatory; the obituarist had even found people who no longer bothered to get dressed. And this dead guy had a lot of clothes. But … generic. Identical. The obituarist looked at them for a bit—looked at the clothes, then looked at the body. Looked at the clothes, then looked at the body. Kept searching. On the dresser he found documents from the dead man’s job, including pictures of the sort of metal balls that had become popular. The obituarist had come upon them in many homes, but not in this one, that of a man who had sold them. He felt curious about this man who’d left him almost nothing to work with: this was a list, not a life. Whatever he’d been inside could hardly be divined by his belongings.

But the belongings didn’t go with what he was piecing together from the body. He thought this, and went to observe it again.

Then he began pacing the tiny apartment, one side to the other, over and over. He stopped. Had the certifiers been able to see him under the neon, they’d have noted that for a second it looked like he was trying to hang in the air. He kept walking. Stopped. Continued. Stopped.

Now he was sure.

He turned to the certifiers and said:

“You can go. Close the door on your way out.”

The certifiers walked out. He could see, beneath the door, the glow of their neon, pulsing. No doubt they were commenting on the obituarist’s behavior.

He took his time going over the furniture, clothes, dresser once more. Without much effort. Almost offhanded. Until again he felt clearly a spot giving off condensed tension, placed the chair in front of it, sat down, took off his badge, and stared at the empty space. After a few seconds he said:

“Who is this man?”

Silence.

The obituarist stood, felt in front of himself for a second, and then pushed the soft blob as hard as he could. Guy’d have no way out of that corner.

That was when the other man took off his buffer. Before the obituarist could make out any details, he got a whiff of the guy’s smell, not a dirty smell or a dusty one but the smell of nervous sweat. Then he saw him. He was a soft man, a man who seemed to have been wearing buffers since before they were even invented. He must have been older than the obituarist, but not as old as the man laid out on the floor. There was plenty of hair on his head, and it was neatly combed.

“Who is he?” the obituarist said.