Ten Year Stretch E-Book

6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: No Exit Press

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

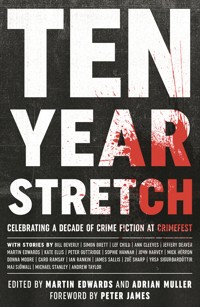

How Many Cats Have You Killed? by Mick Herron and Strangers in a Pub by Martin Edwards from Ten Year Stretch are longlisted for the CWA Short Story Dagger Twenty superb new crime stories have been commissioned specially to celebrate the tenth anniversary of Crimefest, described by The Guardian as 'one of the fifty best festivals in the world'. A star-studded international group of authors has come together in crime writing harmony to provide a killer cocktail for noir fans; salutary tales of gangster etiquette and pitfalls, clever takes on the locked-room genre, chilling wrong-footers from the deceptively peaceful suburbs, intriguing accounts of tables being turned on hapless private eyes, delicious slices of jet black nordic noir, culminating in a stunning example of bleak amorality from crime writing doyenne Maj Sjowall. The foreword is by international bestselling thriller writer Peter James. The editors are Martin Edwards, responsible for many award-winning anthologies, and Adrian Muller, CrimeFest co-founder. All Royalties are donated to the RNIB Talking Books Library.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

TEN YEAR STRETCH

The twenty brand-new crime stories in this book have been specially commissioned to celebrate the tenth anniversary of CrimeFest, described by the Guardian as ‘one of the 50 best festivals in the world’. Contributors come from around the world and include the legendary Maj Sjöwall who, together with partner Per Wahlöö, was the originator of Nordic noir. The editors are Martin Edwards, responsible for many award-winning anthologies and Adrian Muller, one of the co-founders of CrimeFest.

Contributors

to Ten Year Stretch are:

Bill Beverly, Simon Brett, Lee Child, Ann Cleeves, Jeffery Deaver, Martin Edwards, Kate Ellis, Peter Guttridge, Sophie Hannah, John Harvey, Mick Herron, Donna Moore, Caro Ramsay, Ian Rankin, James Sallis, Zoë Sharp, Yrsa Sigurðardóttir, Maj Sjöwall, Michael Stanley and Andrew Taylor.

Dedicated to Jane Burfield, without whose generosity this project would not have been possible

Peter James

Peter James’ Roy Grace detective novels have sold over 19 million copies worldwide, have had 12 consecutive Sunday Times No 1s and are published in 37 territories. Peter has won many literary awards, including the publicly voted ITV3 Crime Thriller Awards People’s Bestseller Dagger, WH Smith readers’ The Best Crime Author of All Time, and the Crime Writers’ Association’s Diamond Dagger Award.

peterjames.com

Foreword

When my first novel, a not very good spy thriller called Dead Letter Drop, was published in 1981, my then publishing contract with WH Allen stipulated the book must be a minimum length of 50,000 words. My finished book was a hair’s whisker just over that minimum, clocking in at a skeletal – by today’s standards – 203 pages.

At the WH Allen Christmas drinks party, the Sales Director came up to me and asked if I could please write a bigger book next time, as the fatter the book, the better perceived value it was to the consumer – as they were all the same price!

Twenty-five years later my publishing contracts for my Roy Grace and other novels require a minimum of 80,000 words.

When Adrian and Miles asked if I would write the foreword to this terrific anthology, with contributions by the A-list of crime writing, it set me thinking about two questions. Firstly, does size matter? And secondly, how do we define a short story? Indeed, in today’s increasingly short-attention-span world, just how blurred are the boundaries defining fiction?

How short does a short story need to be before it becomes a novella? And when does a novella become a novel?

Ernest Hemingway is credited with writing the shortest story in all of fiction with his intensely powerful and moving six words: For sale, baby shoes, never worn. Another I love is the anonymously attributed: The last man on earth sat alone in a room. There was a knock on the door.

The origins of the short story are unclear, but what is certain is that they go back to the earliest roots of storytelling. Aesop’s fables, like ‘The Tortoise and the Hare’, written around 620 BC, are among the first examples. My favourite is the one about the wolf and the lamb:

The wolf, meeting a lamb that had strayed from the fold, resolved not to lay violent hands on him, but to find some plea to justify to the lamb his right to eat him. So he addressed him by saying:

‘Lamb, last year you grossly insulted me.’

‘Indeed,’ bleated the lamb in mournful tone of voice. ‘I was not then born.’

‘Then,’ said the wolf, ‘you fed in my pasture.’

‘No sir,’ replied the lamb. ‘I have not yet tasted grass.’

‘OK,’ the wolf said. ‘You’ve drunk from my well.’

‘No!’ protested the lamb. ‘I’ve never drunk water, because up until now my mother’s milk is both my food and drink.’

Immediately the wolf seized him and ate him, saying, ‘Well! I won’t remain hungry, even though you refute all my allegations.’

The tyrant will always find a pretext for his tyranny.

Aesop’s vast canon of fables were morality tales. Each one leaves us thinking, amused, shocked, pensive. There are few novelists, past or present, who have not written short stories. I love writing them, but I find them incredibly hard – it may sound an odd thing to say, but in many ways I find it easier to write a novel of 120,000 words than a short story of just 2,000. In a full-length novel you have the luxury to explore characters, set up dramatic scenes, and to put in diversion and even red herrings. In the short story you have, constantly, the memory of those six words of Hemingway on your neck, like an albatross.

Or the elephant in the room, perhaps?

In 1814 the Russian poet, Ivan Andreevich Krylov, wrote a fable – or short story, depending on your definition – called ‘The Inquisitive Man’. It was about a man who goes to a museum and notices all kinds of tiny things, but fails to notice an elephant.

The true beauty of short stories is that they enable all of us to explore themes about the human condition in a sharp, succinct way, free of the constraints of the diktats of a novel. Dip into this anthology and pull out the nuggets of characters, situations, life in the raw. You’re going to have a rough ride, your eyes jerked wide open, and a good time, for sure!

Peter James

peterjames.com

Introduction

Ten Year Stretch is a special book to celebrate a special occasion. This collection of brand-new stories by leading crime writers marks the tenth anniversary of CrimeFest, a convention in Bristol for everyone who loves the crime genre. During the past decade, CrimeFest has grown steadily, and is now a ‘must’ for readers and writers alike. The atmosphere is relaxed and convivial, the panels, interviews, and talks invariably of high quality. No wonder the Guardian described CrimeFest as one of the fifty best festivals in the world.

The genesis of this book can be traced to the generosity of one woman, an enthusiastic delegate right from CrimeFest’s early days. Jane Burfield, a benefactor of the arts in her home country of Canada, approached CrimeFest organisers Myles Allfrey, Donna Moore and Adrian Muller with the idea of offering sponsorship to mark the convention’s ten-year milestone. Ten Year Stretch is the result. What better way to promote crime fiction than a collection of fresh work by some of the world’s leading practitioners, all of whom have previously attended and who enjoy an especially warm relationship with CrimeFest?

The concept of a celebratory anthology reflecting CrimeFest’s international flavour was immediately attractive, and so was the suggestion that profits should go to the Royal National Institute of Blind People, for which CrimeFest has raised substantial funds over the years. The support of two very good publishers, No Exit Press in the UK, and Poisoned Pen Press in the US, was enlisted. I was delighted to be asked to become editor – who wouldn’t seize the chance to become the first to read a brand-new story by Lee Child, Jeffery Deaver, Ian Rankin, or…?

The list of illustrious names goes on, as a glance at the contents page reveals. Of course, globally bestselling authors are much in demand, and have countless calls on their time. But the support that the distinguished contributors have so readily and generously given to this project has been striking. There could be no clearer illustration of the regard in which members of the crime-writing world hold CrimeFest.

Scandinavian crime fiction has enjoyed enormous popularity in recent years, and CrimeFest has welcomed leading exponents of Scandi noir along with talented authors from right across the globe. Three years ago, Maj Sjöwall, half of the legendary team of Sjöwall and Wahlöö who were responsible for ten superb and ground-breaking books featuring Martin Beck, was a guest of honour. Maj has – to universal regret – not published a crime novel for more than forty years, but to our delight she agreed to allow publication of one of her short stories, which has been freshly translated into English for the first time.

Plenty of other unpredictable treats are to be found within these pages, as you might imagine with contributors as varied as James Sallis, Yrsa Sigurðardóttir, Michael Stanley, Sophie Hannah, and Simon Brett. There are nods to the traditions of the genre in general, and to the ‘locked room mystery’ in particular, as well as a glance into the future. Two stories introduce new detective characters who may just return again to solve further cases one day. My belief is that a good crime anthology offers an eclectic mix of stories, something (I hope) for everyone who loves the genre. The contributors have certainly delivered.

I’ve been lucky enough to take part in CrimeFest conventions right from the outset, and I’ve never missed one. Like many other people, I have lots of happy memories of time spent at the Marriott Hotel in the second half of May. Not just the programmed events, either. Conversations at the bar, Crime Writers’ Association get-togethers, drinks and meals with a host of delightful authors (yes, and publishers and agents too!), awards ceremonies, even the occasional award – you name it. The convention has become a hugely popular gathering-place where writers mingle with fans from Thursday afternoon until lunchtime on Sunday. In 2017, it was even the unlikely setting for an impromptu meeting of the Icelandic chapter of the CWA. With CrimeFest, as with a good crime story, you should always expect the unexpected. And you can certainly expect to have fun.

The crime-writing community is a warm and generous one, and Jane’s support of Ten Year Stretch, which enables the organisers to present a complimentary copy to every delegate at CrimeFest 2018, is a very good illustration of that enduring truth. I’d like to thank all the contributors (and Maj’s translator!), as well as the publishers. Most of all I’d like to thank Adrian, Donna, Myles, and other team members – such as Liz Hatherell – whose hard work makes CrimeFest such a wonderfully friendly convention. Here’s to the next ten years…

Martin Edwards

martinedwardsbooks.com

Bill Beverly

Bill Beverly teaches at Trinity University in Washington, DC. His debut novel Dodgers (No Exit Press) won the Gold Dagger and John Creasey New Blood Dagger from the CWA, the British Book Award, and the Los Angeles Times Book Prize. His dissertation on criminal fugitives became the book On the Lam: Narratives of Flight in J Edgar Hoover’s America.

The Hired Man

Rent was due in four days. My first check would come in five. Neither date was flexible, I’d been assured. My roommates: let’s just say the vacancy was because they’d burned the last roommate’s shit and beaten him up when he complained. The house was a short walk from the bus lines on Lake and Hennepin, nice old rooms, an attic that smelled of good wood. And four guys to say hi to every day: Bjorn, Rik, Erik, and Henry.

But they were jackals. Four chairs around the table. A calendar in the kitchen with one day circled: rent due.

I’d spent my first three weeks and all my money in Minneapolis trying to find work. The fourth week I’d labored at the Northern, scratching up my next month’s rent. As for my employer: well, Cook told me not even to ask Manager, Curtisall, for an advance on pay. I’d gone straight to Curtisall anyway. He shook his head. ‘That’s something you’d have to ask Johnny Bronco.’

‘Who is Johnny Bronco?’

‘Mr Bronco,’ said Curtisall, ‘is the friend of the man who owns the Northern.’

‘Pardon me, but what the fuck do I care about this friend?’

I’d shown up on time for work every day so far, and I had already been promoted. So I was feeling my oats. But Curtisall shushed me and flashed two L shapes with his thumbs and first fingers. I said, ‘What’s that?’

‘Guns,’ said Curtisall, ‘these hands are guns, Ice Cream. They have guns where you come from?’

I guess I was stupid, because Curtisall added, ‘You don’t ask the Twin Cities mob if you can get your check early. Even one day.’ And then he said not to curse in the restaurant. For Minneapolis runs on its manners, Curtisall reminded me.

* * *

I was moved up from Bus to Ice Cream my second day – it just wasn’t that good a restaurant anymore. On the third day, just before closing, the man in the blue suit came through the dingy white chute of a kitchen to the ice cream counter. I was still learning everything. I read the notes off the wall, recipes and instructions, for every dish, even the things I’d made fifty times already, like banana splits. At the Northern, scoops had to be round and tight. One scoop went in the round dishes, two in the wide, and for two, the instructions said something like, The scoops should match each other like buttocks, same size, same roundness. The notes said how much whipped cream went on the sundaes and where the nuts on a banana split went and how much chocolate you put in a chocolate malt. I would have thought it was all chocolate.

Suddenly the old man stood beside me. He said, ‘You the new Ice Cream?’

‘That’s me,’ I said. Cook. Dishes. Waitress. The bartender was Keep. I’d been Bus and today they had a new Bus but he was a black kid about seventy-nine pounds, he could barely heft a tub, might have been eleven or twelve. He wasn’t gonna make it.

‘Ice Cream, you are doing a damn good job,’ the old man said, and slapped me on the chest. When I looked down, there was the top inch of a fifty poking out of my shirt pocket.

The only fifty I had.

‘Thanks,’ I said. ‘Good to hear.’

‘I might look old,’ he said, ‘but I know how to swim with the current. You make them just right. That vanilla malted’ – I dully recalled making it, twenty minutes ago – ‘most of these bastards, not enough soda water, they make it too sweet.’

Catching the spirit of the moment now, I said, ‘I’ll be sure of it.’

‘Most of them,’ he said, ‘they never should have become Ice Cream in the first place. You aren’t like them.’

Not like them. Where had I heard that? The week before, when I’d finally got my courage up to go visit Ingrid Ericsson, my college classmate, the day before I dragged myself into the Northern (where the help wanted sign had been so long in the window that its red had faded to yellow). I had caught the Lake Street bus over to St Paul, hoping to find Ingrid home – I had left two phone messages and talked to her once, for a feverish half-minute, until she had to break off to go sit down to dinner – and come to find out that the buses weren’t cooled, or this one wasn’t. By the time I disembarked, I was just a sweaty kid aswim in my blazer and blue tie, and now I was introducing myself to Ingrid’s mother, on the front step of the Ericsson house, where Ingrid, unfortunately, was not in. Mrs Ericsson asked me was I Swedish or Norwegian or Danish. None of them, I said, my parents met in Valdosta. She smiled tightly. It was not going well.

The front step was wide and deep, trimmed in marble of bluish-gray, veined with something between green and silver. I took a deep breath and looked up the street. Maybe there are grander streets than Summit Avenue, bigger homes and larger trees, but there was no street anywhere like that in Ocala, Florida, my town. Sure, Ocala had money: we had orange barons and strip club owners and concrete magnates and jai-alai syndicators and mid-level Mafiosi fixing games at the frontons. We had a few old landowners with spreads by the groves, ranches and missions and seven-column plantation mansions. But this boulevard, the dark stolidity, shaded brick and heavy frames and winter-thickened trees with muscular roots – this home, whose address I had memorized long ago from the Student Directory, was the home Ingrid never talked about. She would mention her family’s lake house up past Duluth, and the ranch in Wyoming, its thousands of acres: these places birthed stories, tales of things she’d seen and snakes that reared and a time she broke her arm. These stories were already sepia-toned as she told them, especially when she reminisced about the hired man named LeeRoy, who was so skilled and so funny, and when he’d had a little to drink would do carnival riding tricks atop the horses, feats of strength and dexterity. LeeRoy had died one day, jumped off a horse and just hit funny, Ingrid said, and five minutes later his heart beat its last and they buried him in the field that he loved.

Poor LeeRoy, I’d say, and she’d laugh, her eyes rolling back from the yellow Hawaiian weed I splurged on at home and brought up to school for the occasional hour when she would smoke it with me.

‘Thousands of acres,’ I’d say, rolling another joint. We had never kissed, but we would, given time. In this I had faith. I was putting in the work.

‘Thousands,’ giggled Ingrid Ericsson.

That poor, funny, deceased hired man. Sometimes it felt like I’d known him too. Maybe, there on the front step, I should have said I had. But instead I told Mrs Ericsson, straight up: ‘Your daughter is the reason I came to Minnesota.’

Mrs Ericsson reached out and sampled the damp lapel of my blazer between her fingers. The softly lighted foyer glimmered beyond her, what little beyond her I could see.

‘She has plenty of friends, and some boys with high hopes,’ she said. ‘You aren’t like them.’

‘What does that mean?’

That, Mrs Ericsson did not explain. After barely another minute of discouragement, she excused herself, asking if I knew where the bus stop was. I walked back to Marshall Avenue and caught a bus back across the river.

St Paul was built on these great avenues running east to west, named for men – the Marshalls, the Daytons, the Jeffersons – whose ambition and energy had run east to west, straight and unbroken. In my Minneapolis neighborhood, all the name streets ran north-south, tight one-way strings in a triangle like an autoharp, tuneless, pinched, in alphabetical order, packed with little Nissans and Mazdas. As if here, men would be less grand, nowhere as grand as the scheme. And even the scheme existed to be hijacked, laid waste by lesser men, men like the one I would become in my interview blazer and tie, if I could ever get somebody to call me back.

* * *

On a Sunday, Waitress had a lot to carry, and sometimes there was a party. That day, bridesmaids. When Curtisall stuck in his head and said, ‘Ice Cream, go out and bus,’ I didn’t complain. I took off my rubber gloves. Bus was cleaning up some disaster in the front window. I headed to the party on the upper level.

On the upper level, we could seat four fours, three twos on the back wall, the big roundtable which went twelve seats without crowding, and the four enclosed booths along the right wall with their fringes of strange wooden beads. Smoking wasn’t allowed, but on the upper level, everything was smoked. It smelled real up there, like a grandfather’s pipe, like cigars.

Sunday’s bridesmaids had fanned out wide – over the whole level. Gifts everywhere. I mean, the lucky couple was going to need counter space. All these women would look at home in Ingrid Ericsson’s foyer on Summit Avenue. Pink gums, white teeth, hard calves below the hem: rollerblading till the snow fell, cross-country all winter.

They were only a couple years older than me, but I didn’t even put on my game face.

I had a gray tub. Filled it twice and came back. I mean, there were fifteen or sixteen of them. I had to step around all of it: the bridesmaids, the chairs, the extra tables they’d shifted over because Why not? They’d all arrived in jackets, though it was August, and everything they’d shed had to be hung up on chairbacks here, in their presence – none of it could go on hangers down front, on the rack below the carved sign that said Since 1913.

The moment, looking back, had three parts. The first was the bridesmaids’ final gift.

The final gift was like some wondrous invention of a century past – a sort of ornamental perpetual motion machine, with ocean-blue marbles scooped up by the tails of a ring of spinning dolphins and flipped to the center, where they rolled out again across a lacquered ocean to the outer rim where the dolphins scooped them again. It made a casino-like clinking and rattling, and the dolphins spun industriously, and who knows what powered it, a battery or a spring or some principle of movement the celebrants had kept from the rest of us, whose motions might by it be someday spared. There were delighted gasps, and I slowed down to watch.

As the bridesmaids vied, taking pictures, the bride-to-be decided that the last traces of luncheon visible along the table would not do. ‘Would you,’ said the bride-to-be, waving inconveniently below her camera phone, ‘take this?’

I wasn’t sure what she meant. But I was mannerly about it. ‘Take what, ma’am?’

‘This.’ She waved the sort of backhand you use to scoot away a gnat.

The this was an enormous cut-crystal tray with divots in it, I could only imagine, for five or six dozen deviled eggs. They had not brought it in full of deviled eggs. Instead, the tray had borne their vast white luncheon cake. Coconut frosting, and full of booze – I could smell it from across the room. It complemented the smokiness.

‘The tray?’ I said. I wasn’t sure what to do. I’d only been Bus for nine or ten hours – I hadn’t encountered all the permutations. Now all the bridesmaids stared. ‘It isn’t our tray,’ I said.

You didn’t want to pick up a crystal tray like this one, not on a good day, much less carry it with your gray battle Bus tub through a minefield of purses and chairs and gift bags strewn. And a third of a cake on it, uneaten. A cake as big as triplets.

Maybe I wasn’t getting it. Maybe my problem was the cake. ‘Your Server can put the cake in a box.’

The bride turned on me, and now I saw the face her husband would see forever. To be honest, I quailed.

‘You don’t want to put a tray like that in the dishwasher,’ I added.

‘I just wanted you to move it,’ she steamed, ‘if you’re not too stupid.’ And then the second thing happened. Immediately the beaded curtains on one booth smashed all a-clatter as the one person there clambered up and came out.

It was the same old guy – vanilla malted, fifty dollars – in the blue suit. He wobbled out past the beads, the hanging light swinging behind the swinging beads, so that suddenly the room became a tiger-rush of light and shadow. He reached out for me, his eyes going big in their sockets.

But I followed the directions, I thought.

The nearest rim of bridesmaids seemed to crumble away from him. The old man’s nostrils whistled once, twice, before I understood what the other hand, the one at his clavicles, meant.

He was choking.

I dropped the Bus tub on top of someone’s purse. I grabbed him, spun him round, slapped my arms around him and found the lowest ribs with my forearms, joined my hands. The lapels of his jacket were damp, curiously hot. He had an old man’s bowl to his belly. But his frame felt so bony, so light.

No time for conversation. I remembered my first aid training, cinched him in, and clenched upwards.

On the very first thrust, a ragged, colorless chunk of something went end-over-end, cleared the bride’s coiffure and disappeared into a gift bag. The old man gurgled and drew air.

The bridesmaids went silent.

I let the man in the blue suit go and asked whether he was all right. He waved his hand, but he didn’t reply, didn’t even look back. With some dignity, he regained his booth, slipping through the beads and taking his place at the table.

And I just picked up the tub and got as far from that cake as I could.

* * *

I told Curtisall, ‘I don’t think I can go up there again. I just gave some old guy the Heimlich, and the party, they were freaking out.’

‘Some old guy? Johnny Bronco?’

Somehow, in circling to the kitchen with my tub of margarita glasses and cake forks, I’d forgotten that the choking man was Johnny Bronco.

‘Stop. Stop, stop,’ said Curtisall, who’d been joking about something with Cook, I hadn’t quite caught what, but I was the joke now. ‘You gave Johnny Bronco a Heimlich maneuver? You, like, grabbed him and hugged him? Was he choking?’

‘Why do you think I did it?’

‘Did he say anything to you?’

‘Not a word. He went back in his booth. What kind of name is Johnny Bronco, anyway?’

‘It’s a beautiful name,’ Curtisall said.

‘I might look old,’ Cook mimicked the old man. ‘But I know how to get through to the youngsters!’

Cook and Curtisall exchanged a glance.

‘You should go home. Right now,’ said Curtisall. ‘I can do Ice Cream. Just – don’t go home. Take twenty dollars and go to the lakes. Take your girl to the lakes.’

He seemed panicked, so I handed him the Bus tub. Stripped off my Ice Cream smock. The twenty he gave me was a ten.

It wasn’t even two o’clock. So I went ahead to the lakes. I walked around Lake Calhoun, Lake of the Isles. High school kids throwing a football. Couples were twenty-five, thirty, forty, fifty. I sat for some time, hours, trying to catch the spirit of being twenty-two in Minneapolis, young, single, free, gainfully employed, on my way up to somewhere, something, anywhere. Anything. It was a crisp bright summer day.

All I could come up with was: I hated Minneapolis. They all knew each other. I hated the connected lakes, all ten thousand of them. I had come five hundred miles to chase a girl who only talked to me because of my dope. I could see the truth, and it wasn’t much thornier than that.

There was one thing to do. Get more dope.

* * *

‘You got a phone call,’ said Bjorn, the youngest of my roommates. For the first day or two, I thought Bjorn and I were going to be friends. He had one of those chin beards that climbs up to tickle the lower lip, inflaming it weird and red, like something you’d uncover petting a guinea pig. He had a collection of records he kept in the living room in open crates, displayed. But when I’d studied them, he said, ‘Is there something I can help you with?’

‘Who called?’ I said.

‘I don’t know.’

‘What did they say?’

‘Not sure,’ said Bjorn. He was sitting at the table circling jobs in the want ads. He already had a job, but he was always getting a new one. All my roommates had jobs. Rik, Erik, and Henry were all entrepreneurs. One was in telecom, the other in sports foods, I forget which.

‘These guys, they’ll fuck you up if you don’t pay on time,’ Bjorn had shared with me, those first days, before the looking-at-the-records thing. ‘By on time, I mean that day, not midnight. Before dinner.’

‘So, by six. Six pm?’ I’d said.

‘If you leave a check in the morning, that would be best,’ said Bjorn. But then I learned he’d been as cruel to the last roommate as anyone. He was the one who struck the match.

* * *

I slept fine. I’d picked up an irksome sunburn, hanging out at the lakes half the afternoon. The next day was Monday and my shift started at eleven. If you ordered ice cream before eleven, you got whatever Cook could make you. Or maybe Dishes.

Curtisall saw me coming in the door and he slid in beside me and took me to the bar.

‘Didn’t you listen?’

I said, ‘I’m not sure what you mean.’ Curtisall was standing, but I took a stool at the bar, put my elbows up. It was a nice bar, the Northern’s, the best part of the place, old neons glowing in the corners: Grain Belt. Gluek’s. Kato. I couldn’t afford a drink there, but it was nice to sit. The bartender didn’t report till 11 either, so if you ordered a Manhattan, you got whatever Cook could make you. Or maybe Dishes.

Curtisall was sniffly. He had a cocaine thing. I didn’t judge. It wasn’t pretty, being a manager.

‘I told you never to come back here.’

‘You told me to take my girl to the lakes.’

‘That means to never come back. I even gave you twenty dollars.’

‘I don’t even have a girl,’ I said. ‘You gave me ten. You’re firing me?’

‘It’s not that,’ said Curtisall. ‘It’s Johnny Bronco. You never should have touched him.’

‘I should have let him choke? What about a thank you?’

Curtisall dithered with his hands. He reached over the bar, drew out a glass that was mostly clean, and poured me a long drink of red. ‘Thank you,’ he said. ‘Is that sufficient? College boy? Can we move along now? Here are the undisputed facts. You grabbed a gang lieutenant, Johnny Bronco, by the ass.’

‘I grabbed him,’ I said, beginning, maybe, to understand. ‘I grabbed him around, and then, I guess, that’s what I did.’

‘I don’t need the blow-by-blow. Do you understand that a whole crew of starlets saw you humping the guy?’

‘I wasn’t humping him.’

‘There are pictures,’ Curtisall said. ‘I know what you think. But no one gives a shit what you think.’

I opened my mouth, but he had a point.

‘Curtisall, how many bridesmaids are there,’ I asked, ‘in a typical wedding?’

Curtisall shrugged. ‘Maybe four,’ he said. ‘That wasn’t typical.’

‘I wasn’t humping him.’

‘Kid,’ Curtisall said, and then he poured himself a red too. We drank in silence, him sniffling and dabbing a little at the finish on the bar top, me thinking: Maybe I am a grown-up now. I’d had my first legal drink a year before, my first whiskey with my ex-father at fifteen, my first tequila sick at twelve. But this silence in the bar felt like a debut of sorts.

Curtisall finished his drink, fumbled the glass into the sink. We both pretended we hadn’t heard it break. ‘Anyway, you should get the fuck out of here. Because – I hate to spell it out for you – but you embarrassed him. He might need to hurt you.’

‘To hurt me?’ I said, with an unfortunate chirp.

‘You embarrassed him,’ Curtisall said again.

‘So you’re not on my side in this. You’re firing me. Can I get paid today then?’

‘Friday,’ said Curtisall.

Four more days. ‘What if I’m not around?’

‘We mail it to the address on file,’ Curtisall said.

‘If you were a better manager,’ I said, realizing, with one gulp of wine left, that he was conceding me the right to be pissed off, ‘you’d front a kid his week of pay when he gets fired. Because he saved a mobster’s life.’

‘I know, Ice Cream,’ Curtisall said. ‘I know.’

That was the third part of the moment.

‘If I’d trained you better,’ Curtisall said, ‘you’d know it: back slaps before the abdominal thrusts.’

Now I was rubbing at clouds in the varnish too. ‘I went for it.’

‘Brave of you.’ He stood and tossed my glass to break beside his in the sink. ‘Now beat it, kid.’

* * *

At the big post office on 31st, I changed my address. You filled in name and particulars on a small, gray form of incalculable cheapness. So cheap and grimy that it felt impossible that anyone would ever read it. Yet the address change form worked. I’d done it twice already that summer, first when I moved from school to Mom’s. My mom and I drove each other nuts for three days, till I got in the Plymouth and didn’t stop till I had found a room just across the river from Ingrid Ericsson and given half my money for first month’s rent.

Now I rerouted my mail back to my mom’s. There wasn’t much to reroute. But I’d rather she get the check than my roommates.

I fished out Curtisall’s ten-dollar bill and sat in a woody old bar on Lake that had happy hour all afternoon on Mondays: Special Export drafts, a buck apiece. I drank eight, watched TV. The bartender was named Dolores. Other than that, nothing.

I thought about taking the bus over to St Paul, throwing myself on the mercy of Ingrid Ericsson’s father – whom I’d never met. But I had no plan to get past that front step. Chasing Ingrid to Minnesota had been my only plan after college, and it wasn’t good. I hadn’t even wound up in the same city.

Mobsters in Minneapolis. Maybe Curtisall wasn’t kidding. I had the fifty-dollar bill I’d earned for following directions. Maybe that could get me on the first bus, take me down 94 to Chicago. But never all the way back to Ocala.

I walked back, a little crooked, a little drunk, to the house on Girard. I sat down on the porch for once – in the shade with four chairs, savoring my buzz and the falling evening. It was quiet. Really quiet.

Inside, tied up in the hall, where apparently he’d been all this time, lay Bjorn, my roommate. I looked at him: he shook his head. He didn’t make a sound.

I can’t say I minded seeing him trussed in yellow rope. Someone had done it expertly, efficiently – none of this eight-times-around-the-ankle shit you see on TV.

‘Hey, Bjorn, what’s going on, man?’ I said.

His red lip quivered, a warning. He pointed his head at the dining room.

One thing they say about the dead: they all belong. Ashes to ashes. I went in to face the music.

At the table sat my three roommates, quiet too, cuffed together, like three people at a séance, saying strange prayers. Over them stood Johnny Bronco – in a black suit today – casually turning something, which at first I took to be an oversized flashy corkscrew (the bridesmaids had had one with them) but then I recognized as a silver silencer on the tip of a large gray gun.

So this was how it would be. When the killing was all over, they’d say about me: And he was planning to move out that week. He’d even forwarded his mail.

‘Hello, Ice Cream,’ Johnny Bronco said.

‘Hello, Mr Bronco,’ I announced. ‘Curtisall suggested you might come by.’

Johnny Bronco said, ‘We expected you back a couple hours ago.’

‘I went out and had a few beers.’

‘I understand,’ Johnny Bronco said. ‘Say, I met your roommates. They’ve been sitting here waiting with me. And haven’t shit themselves, not a one of them. Commendable.’

My roommates glared. Rik had a gash, bleeding over one eye; Erik, a bloody nose. Henry was unmarked.

I shrugged. ‘How come Bjorn has to lie in the hallway all by himself?’

‘There aren’t enough chairs.’

‘Right.’ And then the courage that burned upon me was like the glory of an afternoon wind. I was twenty-two and ready for anything.

‘So, Mr Bronco, you come to shoot me? Because if so, let’s get it over with. Minneapolis-style.’

The eyes of my three roommates went left-right-left over the dinner table.

Johnny Bronco’s face lit up. ‘Shoot my best Ice Cream?’ He pointed the gun for the first time. At me. It was shiny and ancient at the same time. ‘Kid, there’s something you got to get straight. I wasn’t choking.’

‘It was my first week,’ I said. ‘I was overzealous.’

‘First you’re supposed to use,’ he said, and dropped his aim, stirring the air with the silencer until the right words bubbled up. ‘Back slaps. Back slaps first.’

‘They teach it different ways.’

‘I don’t doubt it,’ Johnny Bronco said. ‘Back slaps is what you’re supposed to use. If you’re following the directions.’

‘Next time,’ I said. ‘Let’s hope it’s never you.’

‘Let’s fucking hope,’ Johnny Bronco said. Then he put away the long, outlandish gun in the pocket of the black suit, which hid it perfectly, silencer and all.

I knew that talking with men for the rest of my life was going to be like this, like taking that first drink with my father. You had to throw it down fast and pretend you liked it, no matter how it tasted. You had to be ready to hurt each other, to be hurt. If you handed off money, do it with a slap. If you smashed one glass, smash the others.

‘I’m sorry, Johnny Bronco,’ I said. And I was. Not that I had saved his life, or embarrassed him. But I’d come in understanding nothing. Four years of college hadn’t taught me a goddamn thing.

‘Ice Cream, forget about it,’ he said.

He considered my roommates, and for a moment he eyed Henry, who was still unmarked.

‘You little pricks. This kid pay rent to you?’

‘Yeah,’ said Rik. ‘Two hundred a month. It’s due Friday.’

‘Was I talking to you? I’m talking to pretty boy here, with the white collar.’

Henry nodded.

‘Well, maybe I might look old, but I get to the point,’ said Johnny Bronco. ‘You baby fucks, you wet green little baby fucks without a spot on you, you can pay his rent. Work it out between you.’

‘Yes, sir,’ Henry said.

In the kitchen, the telephone awakened, ringing ring after ring. But I didn’t care who it was, or if it was even for me.

Johnny Bronco turned to me. ‘Ice Cream. You want to get out of this place?’

I said, ‘It depends on what you mean.’

Simon Brett

Simon Brett has published over a hundred books, many of them crime novels, including the Charles Paris, Fethering, Mrs Pargeter, and Blotto and Twinks series. His extensive comedy writing includes the series After Henry, which was successful on both radio and television. In 2014 he received the Crime Writers’ Association’s highest award, the Diamond Dagger, and in 2016 he was awarded an OBE for services to literature.

simonbrett.com

The Last Locked Room

When I was growing up, I was very close to my grandfather. His name was Dietrich Gartner. I knew he was famous, but I didn’t at first know what he was famous for. It was much later I discovered that he had achieved fame in two distinct areas.

The time I am talking about was 1939. My name was then, as it is now, Barnaby Smithson, known later, in my professional career, as ‘Barney’. My father Alec was in the navy, always away in other parts of the world on increasingly secret missions. My mother, having never really bought into the notion that charity began at home, was out of the house more and more, manically busy with charitable works. So I spent a greater amount of time in my grandfather’s company than many boys of seven would have done.

Dietrich Gartner, though more fluent in the language than many Englishmen, still had a marked German accent. His daughter had shed hers very quickly after marriage, just as she had adjusted her given name Rosa to a more conformable Rosemary. She now lived in England and she consciously suppressed any nostalgia she might have had for her German background. In the same way, she denied that the family was Jewish, an attitude that pained her father, who was proud of his origins. But no, once the family had moved to Brighton, Rosemary Smithson wanted every new person she met to think of her as an ordinary respectable married Englishwoman. Which was why she called her son Barnaby.

And why she gave Barnaby a very detailed list of things he should never say. He too should never admit that his mother’s family was Jewish. Had he known that he had been conceived in Hamburg, where his father was on another secret mission, and before his parents were actually married, he would have been forbidden to say that too. Above all, he should never say that his mother was German. Given the prevailing mood of the British people, Rosemary Smithson did not wish to give any ammunition to potential bullies at the boys’ prep school where her son Barnaby was being processed into an English gentleman.

Unaware of the implications of any of my mother’s proscriptions, I was happy to go along with them. In the cause of domestic harmony, I knew better than to argue with her. She was a woman of violent moods, particularly as my father began to be absent for increasingly long periods. I was never allowed to ask what my father actually did, but I knew it was something clandestine, and probably dangerous. That knowledge built up in me a fascination with secrecy and duplicity, a fascination which spending so much time with my grandfather did nothing to discourage.

Of one part of Dietrich Gartner’s fame I did have an inkling because of the rows of books with his name on the spine, which had pride of place in the sitting room of his mansion flat in Hove. At least, when I say his name, I am not being strictly accurate. The name on the books was Richard Treeting. And I still remember the excitement when my grandfather introduced me to my first anagram. ‘Richard Treeting’, he explained to me, was made up from the letters of ‘Dietrich Gartner’.

I loved the beauty, the simplicity, the pure logic of the construction. It set me on a path of God knows how many hours wasted poring over the grids of crosswords. And led to endless frustration in boring school lessons as I tried to produce a meaningful anagram of my own name, Barnaby Smithson. Compared to the elegance of ‘Dietrich Gartner’ becoming ‘Richard Treeting’, I knew that ‘Toby N Brissanham’ didn’t really cut the mustard. I felt a level of resentment towards my parents for not having provided me with a more versatile name.

It was some years after my grandfather’s death that I found out how apposite his using a pseudonym was. The books he wrote under the name of Richard Treeting were crime novels, specifically in a subgenre very popular in the 1930s. They were ‘Locked Room Mysteries’, in which murder victims were found in locations to which the perpetrator had no evident means of entrance or exit.

My grandfather did not push me to read his own books. He reckoned, quite rightly, that they were too grown up for a seven-year-old. He did, however, encourage me towards Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes stories, for which I developed an early and enduring addiction.

He also talked to me about how he wrote his books. ‘It is all logic, Barnaby,’ he said. ‘As with Sherlock Holmes, it is all based on logic. Every impossible puzzle eventually will yield to logic. It is only when there is no logic that everything else is lost.’

In my early teens, needless to say, I lapped up every available Richard Treeting novel, intrigued by the puzzles, trying to understand their logic, but also feeling that the books provided a link to my much-missed grandfather. And I felt proud of his reputation as a master of the ‘Locked Room’ genre.

It was quite a lot later that I found out the other area of life in which Dietrich Gartner had found fame.

* * *

One of the things I loved about my grandfather was that he spoke in quotations. I don’t mean that he quoted from other people, but that many of his own utterances were so perfectly observed and perfectly phrased that I remember them to this day. Maybe speaking in his second language – and indeed writing in his second language – made him particularly careful about the way he composed his sentences.

To take an example, I remember an incident from early on in that summer of 1939. I was a day boy at my prep school and frequently, when lessons ended, I would go to my grandfather’s flat rather than to our family home. He, I knew, would be there, while my mother’s presence, depending on her charity commitments, was less reliable. I had keys to both places, and would let myself in, unannounced, at either of them. At the mansion block in Hove, I would scamper eagerly up the flights of stairs to the third floor, ‘one from the top’.

My grandfather always acted surprised, as if he was not expecting me, but his ready supply of bitter milk-free tea and pastries betrayed the preparations he had made for my arrival. He always referred to these delicious confections as kuchen. He got them from a specialist shop in Hove, and he always bought enough to give some to Mrs Blaustein, the widow who lived in the flat below his. ‘Mrs Blaustein likes her kuchen.’

My grandfather’s sitting room was wallpapered in dark green. His heavy furniture, dressers, tall chairs and yards of bookshelves, were made of solid, sombre wood. Once there, I always felt as though I was in an impregnable cocoon of safety. In winter, we would snuggle up close to the open fire, blazing in its almost black stone setting; in summer, we sat in front of the vase of fresh flowers always placed in the empty hearth. My grandfather had no char to keep his home clean and tidy. He did everything domestic himself. Apparently, he had cultivated this independence ever since his wife had died of breast cancer in her early forties. But that had been back in Hamburg, long before I was born. He never spoke of his wife, nor did my mother ever mention her mother. For her it would have been a reference to the past she wanted to expunge from the records. I don’t know the reason for my grandfather’s reticence on the subject.

After my post-school hunger had been sated, we would then, according to the weather, play word games or go for a walk along the seafront. On our walks, when we reached the promenade, we always turned left, towards Brighton. Sometimes, once we got to the West Pier, we would part, I on towards the Palace Pier and the home I shared with my mother, he back to his flat. When, occasionally, I turned and watched his frail figure making its way through the crowds, I was aware of his age. While he was talking, Dietrich Gartner and I were contemporaries. When I could not hear his voice, he was an old man.

Those walks were precious times for me. My grandfather made no concession to my age; he talked to me like an adult. And his conversation ranged widely over literature, history and science. But he never spoke about contemporary politics or the way the international situation was developing. It was not that he did not have an interest in such matters; he just did not talk about them to me.

On our walks, there were sometimes treats. In spite of being filled up with his delicious kuchen, I could never resist the offer of a stick of rock, which I would suck avidly, constantly intrigued by how the manufacturers made the word ‘Brighton’ stay in place all through its length. My grandfather gave me many explanations for this phenomenon, but since most of them involved forest-dwelling trolls, I knew he was teasing me.

That particular afternoon, probably June 1939, as we walked along the prom, we passed a man selling brightly coloured balloons, which he filled with gas from a tank behind his stall. There was an infinitely exciting hiss as each rubber neck was attached and removed. I did not ask, but my grandfather could read the envious look I cast towards the precious objects, and he bought me one. A yellow balloon, I remember, yellow like the sun.

‘Do not let it go, Barnaby,’ he said. ‘Maybe I should tie a loop in the string, then we put it around your wrist, it will not fly away…?’

‘No,’ I said. I think my resistance was based on the fact that small children often had reins fixed around their wrists to stop them from straying. And I thought myself far too grown up to need any such encumbrance. ‘I will hold on to it tightly.’

But of course, I didn’t. Within minutes, distracted by a small dog growling at its owner, I had loosened my grip, and could only watch as my yellow balloon lifted vertically until, caught in a cross-wind, it made steady, almost stately, progress out to sea.

I turned to my grandfather in dismay. ‘Ah,’ he said, ‘there go our hopes. They are as vulnerable as that balloon. We have just seen the last glimpse we will have of freedom for many years.’

That’s what I meant when I said he talked in quotations.

* * *

It was not long after that moment on Brighton seafront that my grandfather died. I later found out that the time of death was probably in the small hours. But in those days before mobile phones or excessive consideration of the feelings of the young, no message was sent to my school and it was the end of the day before I knew that something was wrong.

I went, as I so often did, straight to the flat in Hove, in greedy anticipation of black tea and kuchen. As I entered the main doors of the block – no security locks to negotiate back in those days – I felt, as always, into my grey flannel shorts pocket for my grandfather’s key.

But when I arrived on the third-floor landing, ‘one from the top’, I found the closed door blocked by a stout uniformed policeman.

‘Can’t go in, sonny, I’m afraid,’ he said.

‘But I’m going to see my grandfather. That’s where he lives.’

‘Sorry. You can’t go in.’

‘What’s happened?’

‘Don’t you worry about what’s happened, sonny. You go home to your Mum.’

I tried further persuasion, but the policeman remained unmoving both in bulk and argument. So, I followed his instructions and went home, where I found my mother in deep hysterics being looked after by one of her neighbours, whose expression suggested that she had had one too many such calls for emotional support.

I got little information about the circumstances of Dietrich Gartner’s death. Though in a state of deep shock, I sat dry-eyed through his funeral, and hardly heard the reassuring words spoken to me at the post-service reception in the Old Ship Hotel. One word that none of those hushed voices used was ‘murder’.

* * *

Surprisingly, I got more information from school. There was a boy in the class above me called Larkin (nobody possessed a first name at boys’ prep schools in those days). He had a habit of singling me out from the rest of my classmates. The way Larkin behaved towards me could not have been described as ‘bullying’. ‘Taunting’ was nearer the mark. He saw me as someone at whose expense he could get cheap laughs. Some of these, though I did not understand the references at the time, were based on what he had somehow intuited was my Jewish heritage.

Larkin was not a boy to get on the wrong side of. For a start, as boys of ten can, he had suddenly had a growth spurt, and stood a head taller than the rest of his class. Even more impressive was the fact that his father worked for the Brighton Borough Police as a Detective Inspector. To me, fed on Sherlock Holmes stories and my grandfather’s conversation, that had to be the most glamorous profession in the world.

It was a few days after the funeral. Most of the boys in my class were playing an improvised game of cricket, using a tennis ball and a dog-eared school hymn book as a bat. I would have been with them, had I not been cornered behind the library by Larkin.

‘So, Smithson…’ He always started like that, elongating the vowels of my surname so that it sounded like something vaguely unpleasant. ‘It’s not everyone who can say his grandfather was murdered, is it?’

‘Are you saying that mine was?’ I asked uncertainly.

‘Oh yes,’ he replied with great certainty. ‘My old man dropped a few hints about it.’ When Larkin had started at the school, he had referred to his father as ‘Dad’, but he quickly learned to change that. A father who was a Detective Inspector, though impressive to my eyes, did not match up socially to most of the school’s line-up of parents.

‘Of course, he can’t really talk about his work at home – for professional reasons,’ Larkin went on rather pompously, ‘but occasionally he lets things slip.’

‘Oh?’ I said, still not sure whether this was another of his long-winded wind-ups.

‘Your grandfather lived in a mansion flat in Hove, didn’t he?’

‘That’s right.’