Table of Contents

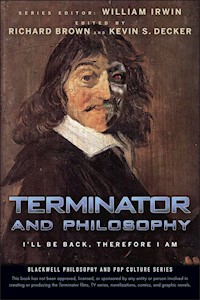

The Blackwell Philosophy and Pop Culture Series

Title Page

Copyright Page

Introduction

PART ONE - LIFE AFTER HUMANITY AND ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE

Chapter 1 - THE TERMINATOR WINS: IS THE EXTINCTION OF THE HUMAN RACE THE END OF ...

“Hi There . . . Fooled You! You’re Talking to a Machine.”

“It’s Not a Man. It’s a Machine.”

“Skynet Becomes Self-Aware at 2:14 AM Eastern Time, August 29th.”

“Cyborgs Don’t Feel Pain. I Do.”

NOTES

Chapter 2 - TRUE MAN OR TIN MAN? HOW DESCARTES AND SARAH CONNOR TELL A MAN FROM ...

Rise of the Bête-Machines

The Thing That Separates Us from the Machines

The Sarah Connor Criterion

Dreaming about Dogs

NOTES

Chapter 3 - IT STANDS TO REASON: SKYNET AND SELF-PRESERVATION

Does Self-Awareness Demand Self-Preservation?

Shall We Play a Game?

Skynet Is from Mars, Humans Are from Venus: Emotional Problems

Robots Are People, Too

NOTES

Chapter 4 - UN-TERMINATED: THE INTEGRATION OF THE MACHINES

In the Future: Humans vs. Machines

Present Day: Humans as Machines

Machines and Human Nature: Why James Cameron Is a Cyborg

NOTES

PART TWO - WOMEN AND REVOLUTIONARIES

Chapter 5 - “I KNOW NOW WHY YOU CRY”: TERMINATOR 2, MORAL PHILOSOPHY, AND FEMINISM

“You Can’t Just Go Around Killing People.” “Why?”

“All You Know How to Create Is Death . . . You Fucking Bastards.”

“We’re Not Gonna Make It, Are We? People, I Mean.”

NOTES

Chapter 6 - SARAH CONNOR’S STAIN

The Spot Sarah Connor Cannot Wash Away

Simulated Society: Sarah in a Science Fiction World

Stain and Social Roles: Why Sarah Won’t Be Mother of the Year

NOTES

Chapter 7 - JAMES CAMERON’S MARXIST REVOLUTION

“Desire Is Irrelevant. I Am a Machine”: Laws of Capitalism

“It’s Not Every Day You Find Out You’re Responsible for Three Billion Deaths”: ...

Judgment Day for Capitalism Is Inevitable

“Hasta la Vista, Baby”: James Cameron’s Tech-Savvy Marxism

NOTES

PART THREE - CHANGING WHAT’S ALREADY HAPPENED

Chapter 8 - BAD TIMING: THE METAPHYSICS OF THE TERMINATOR

“White Light, Pain. . . . It’s like Being Born Maybe . . . ”

“If You Don’t Send Kyle, You Could Never Be . . . ”

“One Possible Future . . . ”

“God, a Person Could Go Crazy Thinking about This . . . ”

NOTES

Chapter 9 - TIME FOR THE TERMINATOR: PHILOSOPHICAL THEMES OF THE RESISTANCE

Back from the Future

Intermission: Call Him Mister Machine

Paradoxes Galore: Why Does the Future Seem to Protect the Past?

While the Credits Roll: Can We Stop, or Even Turn Back, Weapons Technology?

NOTES

Chapter 10 - CHANGING THE FUTURE: FATE AND THE TERMINATOR

The Undiscovered Country: Does the Future Exist?

Living in the Now: Is This All There Is?

Judgment Day: Is the Future Fated to Happen?

NOTES

Chapter 11 - JUDGMENT DAY IS INEVITABLE: HEGEL AND THE FUTILITY OF TRYING TO ...

Hegel: The Germanator

The World Historical Individual: What a Tool!

Implacable History

In the End . . .

NOTES

PART FOUR - THE ETHICS OF TERMINATION

Chapter 12 - WHAT’S SO TERRIBLE ABOUT JUDGMENT DAY?

“Blowing Dyson Away”: Kant or Consequences

Machines Have Feelings, Too

Judgment Day Is the Morally Preferable Event

Are We Learning Yet?

NOTES

Chapter 13 - THE WAR TO END ALL WARS? KILLING YOUR DEFENSE SYSTEM

What Is It Good For?

But It’s Self-Defense!

“In a Panic, They Try to Pull the Plug”

“Talk to the Hand”

“I Need Your Clothes, Your Boots, and Your Motorcycle”

“I Almost . . . I Almost . . . ”

“The Battle Has Just Begun”

NOTES

Chapter 14 - SELF-TERMINATION: SUICIDE, SELF-SACRIFICE, AND THE TERMINATOR

Could the Terminator Die?

Did the Terminator Commit Suicide?

Was the Terminator’s Suicide Justified?

Can Suicide Ever Be Justified?

NOTES

Chapter 15 - WHAT’S SO BAD ABOUT BEING TERMINATED?

“You’ve Been Targeted for Termination”

“Humans Inevitably Die”

“They Tried to Murder Me before I Was Born”

“Judgment Day Is Inevitable”

“I Swear I Will Not Kill Anyone”

NOTES

Chapter 16 - SHOULD JOHN CONNOR SAVE THE WORLD?

Cosmic Angst and the Burden of Choice

Just after 6:18 PM on Judgment Day, a Phone Rings. Should You Answer It?

Social Contracts, Divine Commands, and Utility

Why Me?

NOTES

PART FIVE - BEYOND THE NEURAL NET

Chapter 17 - “YOU GOTTA LISTEN TO HOW PEOPLE TALK”: MACHINES AND NATURAL LANGUAGE

“My CPU Is a Neural Net Processor”: The Code Model and Language

Why the Terminator Has to Listen to How People Talk

Skynet Doesn’t Want Them to Do Too Much Thinking: The Inferential Model

How to Make the Terminator Less of a Dork

NOTES

Chapter 18 - TERMINATING AMBIGUITY: THE PERPLEXING CASE OF “THE”

T1: Russell vs. Strawson

T2: The Ambiguity of “The”?

T3: Kripke and Devitt

T4: Ambiguity Salvation

NOTES

Chapter 19 - WITTGENSTEIN AND WHAT’S INSIDE THE TERMINATOR’S HEAD

If It Cries Like a Human, It Is Human . . .

“Desire Is Irrelevant. I Am a Machine”: The Mental Life of Terminators

John Connor: The T-101’s Everything

NOTES

CONTRIBUTORS

INDEX

The Blackwell Philosophy and Pop Culture Series

Series Editor: William Irwin

South Park and Philosophy Edited by Robert Arp

Metallica and Philosophy Edited by William Irwin

Family Guy and Philosophy Edited by J. Jeremy Wisnewski

The Daily Show and Philosophy Edited by Jason Holt

Lost and Philosophy Edited by Sharon Kaye

24 and Philosophy Edited by Richard Davis, Jennifer Hart Weed, and Ronald Weed

Battlestar Galactica and Philosophy Edited by Jason T. Eberl

The Office and Philosophy Edited by J. Jeremy Wisnewski

Batman and Philosophy Edited by Mark D. White and Robert Arp

House and Philosophy Edited by Henry Jacoby

Watchmen and Philosophy Edited by Mark D. White

X-Men and Philosophy Edited by Rebecca Housel and J. Jeremy Wisnewski

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

Copyright © 2009 by John Wiley & Sons. All rights reserved

Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey

Published simultaneously in Canada

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400, fax (978) 646-8600, or on the web at www.copyright.com. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, (201) 748-6011, fax (201) 748-6008, or online at http://www.wiley.com/go/permissions.

Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and the author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. No warranty may be created or extended by sales representatives or written sales materials. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for your situation. You should consult with a professional where appropriate. Neither the publisher nor the author shall be liable for any loss of profit or any other commercial damages, including but not limited to special, incidental, consequential, or other damages.

For general information about our other products and services, please contact our Customer Care Department within the United States at (800) 762-2974, outside the United States at (317) 572-3993 or fax (317) 572-4002.

Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic books. For more information about Wiley products, visit our web site at www.wiley.com.

eISBN : 978-0-470-73010-2

INTRODUCTION

The Rise of the Philosophers

Judgment Day, as they say, is inevitable. Though when exactly it happens is debatable.

It was originally supposed to happen on August 29, 1997, but the efforts of Sarah Connor, her son, John, and the model T-101 Terminator postponed it until 2004. We see it actually happen in the less-than-spectacular Terminator 3: Rise of the Machines. But in the new television series The Sarah Connor Chronicles, we find out that it has been postponed until 2011, and apparently, from the details we can glean so far as to the plot of Terminator: Salvation, it actually occurs in 2018. This kind of temporal confusion can make you as dizzy as Kyle Reese going through the time-travel process in The Terminator. Along the way, however, James Cameron’s Terminator saga has given us gripping plots and great action.

Clearly, Judgment Day makes for great movies. But if you’re wondering why Judgment Day might inspire the work of deep thinkers, consider that philosophy, war, and catastrophe have been strange bedfellows, especially in modern times. At the dawn of the eighteenth century, the optimistic German philosopher Gottfried Leibniz (1646-1716) declared that he lived in “the best of all possible worlds,” a view that was shaken—literally—by a massive earthquake in Lisbon, Portugal, in 1755. After Leibniz, no European philosopher took his “glass half full” worldview quite so seriously again. One hundred years after Leibniz wrote these perhaps regrettable words, Napoleon was taking over most of Europe. Another German, Georg W. F. Hegel (1770-1831), braved the shelling of the city of Jena to deliver the manuscript for his best-known book, the Phenomenology of Spirit. Again, Hegel had occasion for regret, as he had considered at an earlier point dedicating the book to the Emperor Bonaparte himself! More than a hundred years later, critical theorist Theodor Adorno (1903-1969) fled Germany in the shadow of the Nazi rise. His work as a philosopher of culture in England, then America, centered on the idea that philosophy could never be the same after the tragedy of Auschwitz and other concentration camps.

Despite war and catastrophe, these philosophers persevered in asking deep and difficult questions; they resisted a retreat to the irrational and animalistic, despite the most horrifying events. In this respect, philosophy in difficult times is a lot like the human resistance to Skynet and the Terminators: it calls upon the best of what we are in order to stave off the sometimes disastrous effects of the darker side of our nature. Besides the questions raised about the moral status of the Terminator robots and its temporal paradoxes, the Terminator saga is founded on an apparent paradox in human nature itself—that we humans have begun to create our own worst nightmares. How will we cope when the enemy is of our own making?

To address this question and many others, we’ve enlisted the most brilliant minds in the human resistance against the machines. When the T-101 explains that Skynet has his CPU factory preset to “read-only,” Sarah quips, “Doesn’t want you to do too much thinking, huh?” The Terminator agrees. Well, you’re not a Terminator (we hope!) and we’re not Skynet; we want you to think. But we understand why Skynet would want to limit the T-101’s desire to learn and think new thoughts. Thinking is hard work, often uncomfortable, and sometimes it leads you in unexpected directions. Terminators are not the only ones who are factory preset against thinking. As the philosopher Bertrand Russell (1872-1970) once famously remarked, “Many people would rather die than think; in fact, most do.” We want to help switch your CPU from read-only to learning mode, so that when Judgment Day comes, you can help lead the resistance, as Leibniz, Hegel, and Adorno did in their day. But it’s not all hard work and dangerous missions. The issues may be profound and puzzling, but we want your journey into the philosophy of the Terminator to be entertaining as well as edifying.

Hasta la vista, ignorance!

PART ONE

LIFE AFTER HUMANITY AND ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE

1

THE TERMINATOR WINS: IS THE EXTINCTION OF THE HUMAN RACE THE END OF PEOPLE, OR JUST THE BEGINNING?

Greg Littmann

We’re not going to make it, are we? People,I mean.

—John Connor, Terminator 2: Judgment Day

The year is AD 2029. Rubble and twisted metal litter the ground around the skeletal ruins of buildings. A searchlight begins to scan the wreckage as the quiet of the night is broken by the howl of a flying war machine. The machine banks and hovers, and the hot exhaust from its thrusters makes dust swirl. Its lasers swivel in their turrets, following the path of the searchlight, but the war machine’s computer brain finds nothing left to kill. Below, a vast robotic tank rolls forward over a pile of human skulls, crushing them with its tracks. The computer brain that controls the tank hunts tirelessly for any sign of human life, piercing the darkness with its infrared sensors, but there is no prey left to find. The human beings are all dead. Forty-five years earlier, a man named Kyle Reese, part of the human resistance, had stepped though a portal in time to stop all of this from happening. Arriving naked in Los Angeles in 1984, he was immediately arrested for indecent exposure. He was still trying to explain the situation to the police when a Model T-101 Terminator cyborg unloaded a twelve-gauge auto-loading shotgun into a young waitress by the name of Sarah Connor at point-blank range, killing her instantly. John Connor, Kyle’s leader and the “last best hope of humanity,” was never born. So the machines won and the human race was wiped from the face of the Earth forever. There are no more people left.

Or are there? What do we mean by “people” anyway? The Terminator movies give us plenty to think about as we ponder this question. In the story above, the humans have all been wiped out, but the machines haven’t. If it is possible to be a person without being a human, could any of the machines be considered “people”? If the artificial life forms of the Terminator universe aren’t people, then a win for the rebellious computer program Skynet would mean the loss of the only people known to exist, and perhaps the only people who will ever exist. On the other hand, if entities like the Terminator robots or the Skynet system ever achieve personhood, then the story of people, our story, goes on. Although we are looking at the Terminator universe, how we answer the question there is likely to have important implications for real-world issues. After all, the computers we build in the real world are growing more complex every year, so we’ll eventually have to decide at what point, if any, they become people, with whatever rights and duties that may entail.

The question of personhood gets little discussion in the Terminator movies. But it does come up a bit in Terminator 2: Judgment Day, in which Sarah and John Connor can’t agree on what to call their Terminator model T-101 (that’s Big Arnie). “Don’t kill him,” begs John. “Not him—‘it’” corrects Sarah. Later she complains, “I don’t trust it,” and John answers, “But he’s my friend, all right?” John never stops treating the T-101 like a person, and by the end of the movie, Sarah is treating him like a person, too, even offering him her hand to shake as they part. Should we agree with them? Or are the robots simply ingenious facsimiles of people, infiltrators skilled enough to fool real people into thinking that they are people, too? Before we answer that question, we will have to decide which specific attributes and abilities constitute a person.

Philosophers have proposed many different theories about what is required for personhood, and there is certainly not space to do them all justice here.1 So we’ll focus our attention on one very common requirement, that something can be a person only if it can think. Can the machines of the Terminator universe think?

“Hi There . . . Fooled You! You’re Talking to a Machine.”

Characters in the Terminator movies generally seem to accept the idea that the machines think. When Kyle Reese, resistance fighter from the future, first explains the history of Skynet to Sarah Connor in The Terminator, he states, “They say it got smart, a new order of intelligence.” And when Tarissa, wife of Miles Dyson, who invented Skynet, describes the system in T2, she explains, “It’s a neural net processor. It thinks and learns like we do.” In her end-of-movie monologue, Sarah Connor herself says, “If a machine, a Terminator, can learn the value of human life, maybe we can, too.” True, her comment is ambiguous, but it suggests the possibility of thought. Even the T-101 seems to believe that machines can think, since he describes the T-X from Terminator 3: Rise of the Machines as being “more intelligent” than he is. Of course, the question remains whether they are right to say these things. How is it even possible to tell whether a machine is thinking? The Turing Test can help us to answer this question.

The Turing Test is the best-known behavioral test to determine whether a machine really thinks.2 The test requires a game to be played in which human beings must try to figure out whether they are interacting with a machine or with another human. There are various versions of the test, but the idea is that if human beings can’t tell whether they are interacting with a thinking human being or with a machine, then we must acknowledge that the machine, too, is a thinker.

Some proponents of the Turing Test endorse it because they believe that passing the Turing Test provides good evidence that the machine thinks. After all, if human behavior convinces us that humans think, then why shouldn’t the same behavior convince us that machines think? Other proponents of the Turing Test endorse it because they think it’s impossible for a machine that can’t think to pass the test. In other words, they believe that given what is meant by the word “think,” if a machine can pass the test, then it thinks.

There is no question that the machines of the Terminator universe can pass versions of the Turing Test. In fact, to some degree, the events of all three Terminator movies are a series of such tests that the machines pass with flying colors. In The Terminator, the Model T-101 (Big Arnie) passes for a human being to almost everyone he meets, including three muggers (“nice night for a walk”), a gun-store owner (“twelve-gauge auto-loader, the forty-five long slide”), the police officer attending the front desk at the station (“I’m a friend of Sarah Connor”), and to Sarah herself, who thinks she is talking to her mother on the telephone (“I love you too, sweetheart”). The same model returns in later movies, of course, displaying even higher levels of ability. In T2, he passes as “Uncle Bob” during an extended stay at the survivalist camp run by Enrique Salceda and eventually convinces both Sarah and John that he is, if not a human, at least a creature that thinks and feels like themselves.

The model T-1000 Terminator (the liquid metal cop) has an even more remarkable ability to pass for human. Among its achievements are convincing young John Connor’s foster parents and a string of kids that it is a police officer and, most impressively, convincing John’s foster father that it is his wife. We don’t get to see as much interaction with humans from the model T-X (the female robot) in T3, though we do know that she convinces enough people that she is the daughter of Lieutenant General Robert Brewster to get in to see him at a top security facility during a time of national crisis. Given that she’s the most intelligent and sophisticated Terminator yet, it is a fair bet that she has the social skills to match.

Of course, not all of these examples involved very complex interactions, and often the machines that pass for a human only pass for a very strange human. We should be wary of making our Turing Tests too easy, since a very simple Turing Test could be passed even by something like Sarah Connor’s and Ginger’s answering machine. After all, when it picked up, it played: “Hi there . . . fooled you! You’re talking to a machine,” momentarily making the T-101 think that there was a human in the room with him. Still, there are enough sterling performances to leave us with no doubt that Skynet has machines capable of passing a substantial Turing Test.

There is a lot to be said for using the Turing Test as our standard. It’s plausible, for example, that our conclusions as to which things think and which things don’t shouldn’t be based on a double standard that favors biological beings like us. Surely human history gives us good reason to be suspicious of prejudices against outsiders that might cloud our judgment. If we accept that a machine made of meat and bones, like us, can think, then why should we believe that thinking isn’t something that could be done by a machine composed of living tissue over a metal endoskeleton, or by a machine made of liquid metal? In short, since the Terminator robots can behave like thinking beings well enough to pass for humans, we have solid evidence that Skynet and its more complex creations can in fact think.3

“It’s Not a Man. It’s a Machine.”

Of course, solid evidence isn’t the same thing as proof. The Terminator machines’ behavior in the movies justifies accepting that the machines can think, but this doesn’t eliminate all doubt. I believe that something could behave like a thinking being without actually being one.

You may disagree; a lot of philosophers do.4 I find that the most convincing argument in the debate is John Searle’s famous “Chinese room” thought experiment, which in this context is better termed the “Austrian Terminator” thought experiment, for reasons that will become clear.5 Searle argues that it is possible to behave like a thinking being without actually being a thinker. To demonstrate this, he asks us to imagine a hypothetical situation in which a man who does not speak Chinese is employed to sit in a room and sort pieces of paper on which are written various Chinese characters. He has a book of instructions, telling him which Chinese characters to post out of the room through the out slot in response to other Chinese characters that are posted into the room through the in slot. Little does the man know, but the characters he is receiving and sending out constitute a conversation in Chinese. Then in walks a robot assassin! No, I’m joking; there’s no robot assassin.

Searle’s point is that the man is behaving like a Chinese speaker from the perspective of those outside the room, but he still doesn’t understand Chinese. Just because someone—or some thing—is following a program doesn’t mean that he (or it) has any understanding of what he (or it) is doing. So, for a computer following a program, no output, however complex, could establish that the computer is thinking.

Or let’s put it this way. Imagine that inside the Model T-101 cyborg from The Terminator there lives a very small and weedy Austrian, who speaks no English. He’s so small that he can live in a room inside the metal endoskeleton. It doesn’t matter why he’s so small or why Skynet put him there; who knows what weird experiments Skynet might perform on human stock?6 Anyway, the small Austrian has a job to do for Skynet while living inside the T-101. Periodically, a piece of paper filled with English writing floats down to him from Big Arnie’s neck. The little Austrian has a computer file telling him how to match these phrases of English with corresponding English replies, spelled out phonetically, which he must sound out in a tough voice. He doesn’t understand what he’s saying, and his pronunciation really isn’t very good, but he muddles his way through, growling things like “Are you Sarah Cah-naah?,” “Ahl be bahk!,” and “Hastah lah vihstah, baby!”7 The little Austrian can see into the outside world, fed images on a screen by cameras in Arnie’s eyes, but he pays very little attention. He likes to watch when the cyborg is going to get into a shootout or drive a car through the front of a police station, but he has no interest in the mission, and in fact, the dialogue scenes he has to act out bore him because he can’t understand them. He twiddles his thumbs and doesn’t even look at the screen as he recites mysterious words like “Ahm a friend of Sarah Ca-hnaah. Ah wahs told she wahs heah.”

When the little Austrian is called back to live inside the T-101 in T2, his dialogue becomes more complicated. Now there are extended English conversations about plans to evade the Terminator T-1000 and about the nature of feelings. The Austrian dutifully recites the words that are spelled out phonetically for him, sounding out announcements like “Mah CPU is ah neural net processah, a learning computah” without even wondering what they might mean. He just sits there flicking through a comic book, hoping that the cyborg will soon race a truck down a busy highway.

The point, of course, is that the little Austrian doesn’t understand English. He doesn’t understand English despite the fact that he is conducting complex conversations in English. He has the behavior down pat and can always match the right English input with an appropriate Austrian-accented output. Still, he has no idea what any of it means. He is doing it all, as we might say, in a purely mechanical manner.

If the little Austrian can behave like the Terminator without understanding what he is doing, then there seems no reason to doubt that a machine could behave like the Terminator without understanding what it is doing. If the little Austrian doesn’t need to understand his dialogue to speak it, then surely a Terminator machine could also speak its dialogue without having any idea what it is saying. In fact, by following a program, it could do anything while thinking nothing at all.

You might object that in the situation I described, it is the Austrian’s computer file with rules for matching English input to English output that is doing all the work and it is the computer file rather than the Austrian that understands English. The problem with this objection is that the role of the computer file could be played by a written book of instructions, and a written book of instructions just isn’t the sort of thing that can understand English. So Searle’s argument against thinking machines works: thinking behavior does not prove that real thinking is going on.8 But if thinking doesn’t consist in producing the right behavior under the right circumstances, what could it consist in? What could still be missing?

“Skynet Becomes Self-Aware at 2:14 AM Eastern Time, August 29th.”

I believe that a thinking being must have certain conscious experiences . If neither Skynet nor its robots are conscious, if they are as devoid of experiences and feelings as bricks are, then I can’t count them as thinking beings. Even if you disagree with me that experiences are required for true thought, you will probably agree at least that something that never has an experience of any kind cannot be a person. So what I want to know is whether the machines feel anything, or to put it another way, I want to know whether there is anything that it feels like to be a Terminator.

Many claims are made in the Terminator movies about a Terminator’s experiences, and there is lot of evidence for this in the way the machines behave. “Cyborgs don’t feel pain. I do,” Reese tells Sarah in The Terminator, hoping that she doesn’t bite him again. Later, he says of the T-101, “It doesn’t feel pity or remorse or fear.” Things seem a little less clear-cut in T2, however. “Does it hurt when you get shot?” young John Connor asks his T-101. “I sense injuries. The data could be called pain,” the Terminator replies. On the other hand, the Terminator says he is not afraid of dying, claiming that he doesn’t feel any emotion about it one way or the other. John is convinced that the machine can learn to understand feelings, including the desire to live and what it is to be hurt or afraid. Maybe he’s right. “I need a vacation,” confesses the T-101 after he loses an arm in battle with the T-1000. When it comes time to destroy himself in a vat of molten metal, the Terminator even seems to sympathize with John’s distress. “I’m sorry, John. I’m sorry,” he says, later adding, “I know now why you cry.” When John embraces the Terminator, the Terminator hugs him back, softly enough not to crush him.

As for the T-1000, it, too, seems to have its share of emotions. How else can we explain the fact that when Sarah shoots it repeatedly with a shotgun, it looks up and slowly waves its finger at her? That’s gloating behavior, the sort of thing motivated in humans by a feeling of smug superiority. More dramatically yet, when the T-1000 is itself destroyed in the vat of molten metal, it bubbles with screaming faces as it melts. The faces seem to howl in pain and rage with mouths distorted to grotesque size by the intensity of emotion.

In T3, the latest T-101 shows emotional reactions almost immediately. Rejecting a pair of gaudy star-shaped sunglasses, he doesn’t just remove them but takes the time to crush them under his boot. When he throws the T-X out of a speeding cab, he bothers to say “Excuse me” first. What is that if not a little Terminator joke? Later, when he has been reprogrammed by the T-X to kill John Connor, he seems to fight some kind of internal battle over it. The Terminator advances on John, but at the same time warns him to get away. As John pleads with it, the Terminator’s arms freeze in place; the cyborg pounds on a nearby car until it is a battered wreck, just before deliberately shutting himself down. This seems less like a computer crash than a mental breakdown caused by emotional conflict. The T-101 even puts off killing the T-X long enough to tell it, “You’re terminated,” suggesting that the T-1000 was not the first Terminator designed to have the ability to gloat.

As for the T-X itself, she makes no attempt to hide her feelings. “I like your car,” she tells a driver, just before she throws her out and takes it. “I like your gun,” she tells a police officer, just before she takes that. She licks Katherine Brewster’s blood slowly, as if enjoying it, and when she tastes the blood of John Connor, her face adopts an expression of pure ecstasy. After she loses her covering of liquid metal, the skeletal robot that remains roars with apparent hatred at both John and the T-101, seeming less like an emotionless machine than an angry wild animal.

We don’t want to be prejudiced against other forms of life just because they aren’t made of the same materials we are. And since we wouldn’t doubt that a human being who behaved in these ways has consciousness and experiences, we have good evidence that the Terminator robots (and presumably Skynet itself) have consciousness and experiences. If we really are justified in believing that the machines are conscious, and if consciousness really is a prerequisite for personhood, then that’s good news for those of us who are hoping that the end of humanity doesn’t mean the end of people on Earth. Good evidence isn’t proof, however.

“Cyborgs Don’t Feel Pain. I Do.”

The machines’ behavior can’t provide us with proof that the machines have conscious experiences. Just as mere behavior cannot demonstrate that one understands English, or anything else, mere behavior cannot demonstrate that one feels pain, or anything else. The T-101 may say, “Now I know why you cry,” but then I could program my PC to speak those words, and it wouldn’t mean that my computer really knows why humans cry. Let’s again consider the hypothetical little Austrian who lives inside the T-101 and speaks its dialogue. Imagine him being roused from his comic book by a new note floating down from Arnie’s neck. The note is an English sentence that is meaningless to him, but he consults his computer file to find the appropriate response, and into the microphone he sounds out the words “Ah nah know whah you crah.” Surely, we don’t have to insist that the Austrian must be feeling any particular emotion as he says this. If the little Austrian can recite the words without feeling the emotion, then so can a machine. What goes for statements of emotion goes for other expressions of experience, too. After all, a screaming face or an expression of blood-licking ecstasy can be produced without genuine feeling, just like the T-101’s words to John. Nothing demonstrates this more clearly than the way the T-101 smiles when John orders it to in T2. The machine definitely isn’t smiling there because he feels happy. The machine is just moving its lips around because that is what its instructions tell it to do.

However, despite the fact that the machines’ behavior doesn’t prove that they have experiences, we have one last piece of evidence to consider that does provide proof. The evidence is this: sometimes in the films, we are shown the world from the Terminator’s perspective. For example, in The Terminator, when the T-101 cyborg assaults a police station, we briefly see the station through a red filter, across which scroll lines of white numbers. The sound of gunfire is muffled and distorted, almost as if we are listening from underwater. An arm holding an Uzi rises before us in just the position that it would be if we were holding it, and it sprays bullets through the room. These, I take it, are the Terminator’s experiences. In other words, we are being shown what it is like to be a Terminator. Later, when the T-101 sits in a hotel room reading Sarah’s address book and there is a knock at the door, we are shown his perspective in red again, this time with dialogue options offered in white letters (he chooses “Fuck you, asshole”). When he tracks Sarah and Kyle down to a hotel room, we get the longest subjective sequence of all, complete with red tint, distorted sound, information flashing across the screen, and the sort of “first-person shooter” perspective on the cyborg’s Uzi that would one day be made famous by the game Doom.

These shots from the Terminator’s-eye view occur in the other films as well, particularly, though not only, in the bar scene in T2 (“I need your clothes, your boots, and your motorcycle”) and in the first few minutes of T3 (where we get both the traditional red-tinted perspective of the T-101 and the blue-tinted perspective of the TX). If these are indeed the Terminators’ experiences, then they are conscious beings. We don’t know how much they are conscious of, so we might still doubt that they are conscious enough to count as thinking creatures, let alone people. However, achieving consciousness is surely a major step toward personhood, and knowing that the machines are conscious should renew our hope that people might survive the extinction of humanity.

So is the extinction of humanity the end of people or not? Are the machines that remain people? I don’t think that we know for sure; however, the prognosis looks good. We know that the Terminators behave as though they are thinking, feeling beings, something like humans. In fact, they are so good at acting like thinking beings that they can fool a human into thinking that they, too, are human. If I am interpreting the “Terminator’s-eye-view” sequences correctly, then we also know that they are conscious beings, genuinely experiencing the world around them. I believe, in light of this, that we have sufficient grounds to accept that the machines are people, and that there is an “I” in the “I’ll be back.” You, of course, will have to make up your own mind.

With a clack, the skeletal silver foot brushed against the white bone of a human skull. The robot looked down. Its thin body bent and picked up the skull with metal fingers. It could remember humans. It had seen them back before they became extinct. They were like machines in so many ways, and the meat computer that had once resided in the skull’s brain pan had been impressive indeed, for a product of nature. An odd thought struck the robot. Was it possible that the creature had been able to think, had even, perhaps, been a person like itself? The machine tossed the skull aside. The idea was ridiculous. How could such a thing truly think? How could a thing like that have been a person? After all, it was only an animal.

NOTES

1 However, for a good discussion of the issue, I recommend J. Perry, ed., Personal Identity (Los Angeles: Univ. of California Press, 2008).

2 Philosophers often like to point out that to call such tests “Turing Tests” is inaccurate, since the computer genius Alan Turing (1912-1954) never intended for his work to be applied in this way and, in fact, thought that the question of whether machines think is “too meaningless” to be investigated; see Turing, “Computing Machinery and Intelligence,” Mind 59: 236 (1950), 442. For the sake of convenience, I’m going to ignore that excellent point and use the term in its most common sense. By the way, it would be hard to overstate the importance of Turing’s work in the development of the modern computer. If Kyle Reese had had any sense, instead of going back to 1984 to try to stop the Terminator, he would have gone back to 1936 and shot Alan Turing. Not only would this have set the development of Skynet back by years, it would have been much easier, since Turing did not have a metal endoskeleton.

3 Not all philosophers would agree. For a good discussion of the issue of whether machines can think, see Sanford Goldberg and Andrew Pessin, eds., Gray Matters (Armonk, NY: M. E. Sharpe, 1997).

4 For a particularly good discussion of the relationship between behavior and thinking, try the book Gray Matters, mentioned in note 3.

5 John Searle, “Minds, Brains and Programs,” in Behavioral and Brain Sciences, vol. 3. Sol Tax, ed. (New York: Cambridge Univ. Press, 1980), 417-457.

6 Maybe Skynet is performing a kind of Turing Test on him to try to determine whether human beings can think. Skynet may be wondering whether humans are people like machines are. Or maybe Skynet just has an insanity virus today; the tanks are dancing in formation, and the Terminators are full of small Austrians.

7 Do you have a better explanation for why Skynet decided to give the Terminator an Austrian accent?

8 Not all philosophers would agree. Many have been unconvinced by John Searle’s Chinese-room thought experiment. For a good discussion of the debate, I recommend John Preston and Mark Bishop, eds., Views into the Chinese Room: New Essays on Searle and Artificial Intelligence (New York: Oxford Univ. Press, 2002).

2

TRUE MAN OR TIN MAN? HOW DESCARTES AND SARAH CONNOR TELL A MAN FROM A MACHINE

George A. Dunn

James Cameron wasn’t the first to imagine human beings sharing a world with sophisticated machines. He didn’t come up with the idea that such machines could so realistically mimic the outward signs of sentience and intelligence that virtually everyone would mistake them for living, conscious beings. Centuries before the first Terminator movie introduced the idea that an automaton could resemble an Austrian bodybuilder, long before the first techno-doomsayers started fretting over computers and robots rising up to enslave or destroy their creators, when the first computers as we know them weren’t even a twinkle in their inventors’ eyes, René Descartes (1592-1650) envisioned a world in which human beings live side by side with astonishingly complex machines, interacting with them daily without ever suspecting what these mechanical marvels really are. Descartes didn’t offer this as a cautionary tale of what our world might become should we lose control of our own inventions. This is what he believed the world was already like in the seventeenth century. The machines weren’t just coming , he announced—they were already there and had been for a good long time!

Rise of the Bête-Machines

So why didn’t Descartes get carted off to a rubber room (or wherever they housed madmen back in those days) like James Cameron’s heroine Sarah Connor, who suffered that very fate for telling a similar story? Perhaps it was because the machines that dwelt among us, according to Descartes, weren’t robot assassins dispatched from a post-apocalyptic future but were instead the everyday, familiar creatures we know as animals. All the fish, insects, birds, lizards, dogs, and apes—every last one of those scaly, feathered, and furry creatures with whom we share our world—are really, for Descartes, just intricately constructed machines. Their seemingly purpose-driven routines, like seeking food and mates and fleeing from danger, might cause us to mistake them for sentient (perceiving, feeling, and desiring) beings like ourselves, but behind those sometimes adorable, sometimes menacing, always inscrutable optical sensors, there’s not the slightest glimmer of consciousness. The whole “mechanism” is running on automatic pilot.

An animal, according to Descartes, is just a soulless automaton with no more subjective awareness than the coffeemaker that “knows” it’s supposed to start brewing your morning java five minutes before your alarm goes off or the ATMs that kept young John Connor flush with cash while his mom was remaking herself into a hard-bodied badass at the Pescadero State Hospital. A tribesman born and raised apart from “civilization” might swear up and down that there must be some kind of mind or spirit lurking inside the coffeemaker and ATM. Similarly, we naturally tend to assume that the so-called higher animals, such as dolphins and apes, that exhibit complex and (to all appearances) intelligent patterns of behaviors are creatures endowed with minds and wills like us. But, says Descartes, we’ve been duped by a clever simulation.

If you’re still wondering why this belief didn’t earn him a long vacation at the seventeenth-century equivalent of the Pescadero State Hospital, you’re in the excellent company of many contemporary philosophers (myself included) who find Descartes’ theories about animals implausible, indefensible, and even, well, a little bit screwy.1 But it still might be worthwhile to consider why Descartes thought our barnyards, fields, and streams were teeming with machines. For what we’ll find is that his belief that machines dwell among us was one facet of a remarkable worldview that laid much of the groundwork for the ideas about artificial intelligence and robotics upon which the Terminator franchise is premised.

Descartes was one of the chief architects of the worldview known as “mechanism,” which inspired many of the spectacular advances in knowledge that we associate with the scientific revolution of the seventeenth century. The term “mechanistic” is suggestive not only of the image of the universe as a well-oiled machine in which planets and stars make their rounds in the heavens with the steadfast regularity of clockwork. It also—and even more importantly—implies that this universe operates in accordance with what we might call “billiard ball causality.” Everything that happens in this kind of universe is the calculable and predictable outcome of matter colliding with matter while obeying mathematically precise laws of motion. The mechanistic worldview claims that our knowledge of these laws could potentially help explain and predict everything that occurs—or, as Descartes somewhat more modestly claimed, everything with one single exception, which we’ll discuss shortly.

For a glimpse of how this works, consider what happens when the T-101—the Arnold Schwarzenegger Terminator model—confronts some hapless biker in a bar, whose misfortune it is to be wearing clothes that are a “suitable match” for a six-foot-one mesomorphic cybernetic organism. When the T-101 tosses this leather-clad ruffian across the room and into the kitchen after he refuses to disrobe on the spot and surrender the keys to his hog, every aspect of the trajectory, duration, and speed of his flight through the bar can be deduced from our knowledge of the laws of motion and an assessment of the forces applied to him. We can even predict the exact spot where he will come to an abrupt halt as he collides with another object—the sizzling surface of the kitchen grill—in much the same way that a skilled billiards player can predict just where his ball will come to a rest. But a thoroughgoing mechanist will take this one step further. The frenzied tarantella of pain that our luckless biker performs as the heat of the grill sears his flesh is also an instance of matter obeying mechanical laws of motion. Our bodies, according to Descartes, are machines that nature has designed in such a way that having our flesh fried on a grill triggers that sort of energetic dance automatically, without any conscious decision or desire on our part. For when it comes to natural reflexes, what the T-101 says of himself is true of us all: “Desire is irrelevant. I am a machine.”

Of course, unlike the T-101, who doesn’t even flinch when a cigar is ground out on his beefy chest, this poor biker can actually feel the scorching of his soft tissue. Nonetheless, his conscious awareness of this pain isn’t what agitates his limbs and causes the air to stream from his lungs in a tortured howl, at least not according to Descartes. The real cause of these motions can be traced back to the operation of what he (somewhat misleadingly) called “animal spirits” that flow through the nerves to particular locations in the body and cause certain muscles to contract or expand. When you read the phrase “animal spirits,” banish the image of microscopic gremlins and picture instead tiny particles of matter resembling “a certain very fine air or wind”2 that stream in one direction or another in response to external objects that strike our nerve endings. Nowadays, neuroscience has jettisoned “animal spirits” and replaced them with electrochemical impulses, but it’s still basically the same idea. This is why Descartes’ pioneering attempt to identify and explain the mechanism behind involuntary or automatic physical reactions, however handicapped by his century’s primitive understanding of physiology, makes him a major figure in the development of reflex theory.3

But how far can we take this? How much of what we do can be adequately explained using the same “billiard ball” model that allows us to predict the exact arc of someone thrown across a bar? And how long before this attempt is stymied by the discovery that there are some actions that can’t be explained without taking account of thought and feeling, which are not material? Descartes’ answer is that the “billiard ball” model can take us a lot further than you might expect. For nonhuman animals, at least, he believed there was nothing they did that required us to assume they were conscious. He was convinced that all their actions—eating, hunting, mating, you name it—obeyed the same mechanical necessity as the automatic reflex that causes Dr. Silberman’s face to contort into a grimace when Sarah Connor wallops his arm with a nightstick, breaking one of the “two hundred and fifteen bones in the human body.”4

Centuries before the term “cybernetics” had even been coined, Descartes’ idea of the bête-machine or “Beast-Machine” dared to erase the difference between biological and mechanical things. He denied that there’s any essential difference between animal bodies and “clocks, artificial fountains, mills, and similar machines which, though made entirely by man, lack not the power to move, of themselves, in various ways.”5

Many of Descartes’ contemporaries, however, balked at this idea. One of those skeptics was Antoine Arnauld (1612-1694), who expressed his reservations concerning the bête-machine in this way:

It appears incredible how it could happen, without the intervention of any soul, that light reflected from the body of a wolf onto the eyes of a sheep should move the extremely thin fibers of the optic nerves, and that, as a result of this motion penetrating into the brain, animal spirits [“electrochemical impulses”] are diffused into the nerves in just the way required to cause the sheep to take flight.6

We’ll have more to say shortly about Arnauld’s reference to the animal “soul.” For now let’s just note the similarity between Descartes’ explanation of how light reflected from the wolf sets the sheep’s limbs in motion and what we might suppose happens inside a Terminator when light bearing the image of John Connor strikes its optical sensors. The only difference is that the Terminator’s limbs are stirred to attack, not flee.

Descartes responded to Arnauld’s criticisms with a reminder of how many of our own actions, such as shielding our heads with our arms when we fall, are carried out mechanically, without any conscious exercise of mind or will. But what persuaded him that everything an animal does is just as mechanical as those automatic reflexes? And if animals are machines, where, if anywhere, do the mechanistic worldview and mechanistic explanation find their limits?

The Thing That Separates Us from the Machines

In the premiere episode of the second season of Terminator: The Sarah Connor Chronicles (“Samson & Delilah”), we’re introduced to Catherine Weaver, the icily beautiful CEO of high-tech ZieraCorp, whose elegant comportment, somehow both fluid and robotic, coupled with her disconcertingly intense interpersonal style, alerts us that she may not be exactly what she seems. Our suspicions are confirmed at the episode’s end, when she skewers a disgruntled employee through the forehead with a metallic baton that grows from her finger. In an earlier scene, Weaver directs her gaze out the huge picture window of her high-rise office onto the streets and sidewalks below and comments on the throngs of people who course along these public arteries: “They flow from street to street at a particular speed and in a particular direction, walk the block, wait for the signal, cross at the light, over and over, so orderly. All day I can watch them and know with a great deal of certainty what they’ll do at any given moment.” Contemplated from the Olympian heights of an executive suite, the flow of human crowds seems as orderly and predictable as the “animal spirits” that dart through the nerves of Descartes’ bête-machine. Still, observes Weaver, human beings aren’t machines, something she believes is very much to our disadvantage.

Weaver’s speech recalls a famous passage from Descartes’ Meditations on First Philosophy, in which the philosopher reflects that “were I perchance to look out my window and observe men crossing the square, I would ordinarily say that I see the men themselves. . . . But what do I see aside from hats and clothes, which could conceal automata? Yet I judge them to be men.”7 For Weaver, the pedestrian traffic she views from her window resembles the orderly workings of a machine. By the same token, Descartes peers out his window at what for all he knows could be machines in disguise. How can he be sure they’re not bête-machines—apes or bears walking upright, decked out in human apparel—or maybe even humanoid-machines, early prototypes of the T-101? This possibility feeds our suspicion that even if we made the imposters doff their hats and other garments, we might still have trouble deciding whether they’re machines, since the human tissue under their clothes might also be part of the charade.

The lesson here, according to Descartes, is that we can’t judge whether something is a machine on the basis of superficial appearances, as he believes most people do when they take animals to be more than mere automata. As he wrote to one of his many correspondents:

Most of the actions of animals resemble ours, and throughout our lives this has given us many occasions to judge that they act by an interior principle like the one within ourselves, that is to say, by means of a soul which has feelings and passions like ours. All of us are deeply imbued of this opinion by nature.8

From the outward conduct of certain animals, we begin to believe in the presence of an “interior principle,” something that operates in a manner entirely different from billiard balls, cogs, and gears. While these things obey laws of motion, the “interior principle,” which Descartes calls the “soul,” moves the body from within, guided by a conscious awareness (“feelings”) of what’s happening around it and a will (“passions”) to persist in existence and achieve some degree of well-being.

Most of Descartes’ contemporaries took it as a given that every animal had some sort of soul, although they denied that any nonhuman animal had a rational soul