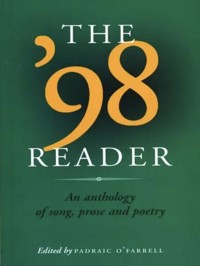

The '98 Reader E-Book

Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The Lilliput Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

Seventeen ninety-eight saw French and American revolutionary ideals converge with popular rebellion in Ireland. The rebellion ended in bloody failure, but 1798 was kept alive in folk memory by a nascent literature added to by succeeding generations of nationalists and cultural revivalists. This wide-ranging gathering of prose, poetry and song mirrors both sides of that conflict, orange and green, imperial and republican, from the early idealism of the 1782 Dungannon Convention to the final snuffing out of resistance in Wicklow in 1803. Here are the legendary ballads and verse accounts of the rebellion, familiar and little known, ranging from those by anonymous balladeers to works by John Keegan Casey, P.J. McCall, Thomas Moore, Thomas Davis, Alice Milligan, William Drennan, William Rooney and Ethna Carbery. These are supplemented by prose accounts by Theobald Wolfe Tone, Charles Teeling, Robert Emmet, Jonah Barrington and Maria Edgeworth, and folk narratives from the archive of the Irish Folklore Department at UCD. The 98' Reader is a delightful companion, recording-and-celebrating-a pivotal moment in Ireland's history.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 387

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 1998

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

The ’98 Reader

Padraic O’Farrell

THE LILLIPUT PRESS

DUBLIN

To Niamh and John

Acknowledgments

I thank Antony Farrell of Lilliput Press for accepting this idea and going through with it. Thanks also to his editor, Brendan Barrington, publicist, Siobán, and Vincent Hurley, who assisted greatly in suggesting material and advising on sources. I wish to thank the Librarians and staffs of the National Library of Ireland and county libraries of Westmeath, Wexford, Meath and Kildare for continuing assistance; the Department of Irish Folklore at University College, Dublin, Professor Bo Almqvist and Eagarthoir,Béaloideasfor permission to quote the account of the Swearing of Billy Byrne and of The Battle of Ballinamuck; Gearóid O’Brien and Seán Ó Rioghbardáin for their interest and help; my daughters, Niamh and Aisling for word-proccessing and my wife, Maureen, for proof-reading.

Foreword

Simply to read the list of contents could be the best introduction to this remarkable, and most moving and informative anthology. It treats only of one year in our Irish history but that was a momentous, and significant year and Padaic O’Farrell allows it to speak, and to sing and recite for itself. I bow before the research work he has done, and the wisdom and lucidity with which he presents his findings.

He sets out from the Church of Dungannon. He gives us the declarations and resolutions made and signed by Wolfe Tone. It is good to look again on that vision and, in this year, to brood over all that went wrong. And if you are a Tyrone man you know that you, or somebody belonging to you, was around for the Battle of Diamond. Then, aided by Teeling, off we go to Bantry and fail, sadly, to encounter Hoche.

There are so many people all around us, the Bold Belfast Shoemaker, and John and Henry Sheares and Napper Tandy. And we pass by the Battle of Prosperous and may meditate on quiet lovely green places that once were bright with steel and dark-red with blood. And these pages give us the comments of the time, much of it wise, much of it fatal.

But the most moving moment in this great boook came, personally, for me when I came to a series of poems of, or related to, the period. The procession began with Florence Wilson’s ‘The Man from God Knows Where’, which when I was a boy I recited, every word of it, at a concert in Omagh Town Hall. Fond memories. I survived. Then after that, but in this this great book, comes ‘A Song of the North’ by Brian naBanban, who was Brian O’ Higgins, father of the Abbey actor, and he and all his family were clear friends of mine. Then comes James Orr’s, ‘Donegore Hill’, and P.J. McCall’s, ‘Henry Joy’, and Ethna Carbery’s, ‘Roddy McCorley’. And on to Alice Milligan, that great lady, meditating on that same fatal year.

And I recall the day, say sixty years ago, when a notable Ulster clergyman, Fr Paul Mackenna, brought me from Omagh town to an old mansion on the fringe of Mountfield village. And he stood at the door and called: ‘Alice, where art thou?’ And the aged poetess came forth. And I, being middling young, felt I was back in 1798.

Benedict Kiely, April 1998

Preface

Just a few weeks of actual combat. Some of the engagements were mere skirmishes, others fierce and bloody. Yet the rebellion of 1798 has inspired more song, prose and poetry than many more significant and strategically conclusive campaigns.

The songs are most remembered. Rural Irish people now in late-middle or old age learned them as children. They did not stop to think of their blood-thirsty lyrics. Fertile young imaginations grasped the imagery of each stanza with fervour. Young arms plucked ash-plants from hedges and fashioned make-believe pikes. Every stream was the Slaney, each high rise was Vinegar Hill. Kelly the Boy from Killane and Father Murphy, each scarcely four feet tall, fought their way across bracken and heather. That was because Wexford had the most stirring selection of ballads.

Only in later years, when history had become a school subject, did they learn about the rising in the North, about Humbert in Killala. Then they remembered their fathers and mothers singing songs or reading poems about those episodes too: ‘Henry Joy’ or ‘The Men of the West’.

The Second World War, with Vera Lynn and her White Cliffs of Dover and Jimmy going asleep in his own little room again, pushed the airs of ‘98 aside. ‘The Shores of Tripoli’ opened the way for American songs. They are still with us!

The prose and poems included here give a more sober view of strife and warfare. Some are included with reluctance, even apprehension, because they tell of sectarian atrocities that are still occurring in part of Ireland, sometimes of similar nature and in the same locations. Because they are of an era in which warfare and violence were acceptable methods of securing rights, they incite and call for continuing strife.

They remind that no account of the rebellion is complete without starting long before 1798 and ending some years after. A chronology, therefore, supports this collection. It begins with the formation of the Volunteers in 1778 and ends with Michael Dwyer’s surrender in 1803.

Early, Early, All in the Spring 1778-96

of stirrings–of organizations – of personalities – of bantry – of oaths

Of Stirrings

A heady awareness of French-inspired republicanism fomented resentment to government brutality and opened the path to bloody and dramatic rebellion. English born American, Thomas Paine (1737-1809) wroteThe Age of Reason(London 1794) and defended the French Revolution inThe Rights of Man Being an Answer to Mr Burke’s Attack on the French Revolution(Dublin 1791). Those who embraced his ideals (for which he was imprisoned briefly in Paris) were called Painites. Paine’s doctrine, with its heady rhetoric like ‘My country is the world and my religion is to do good’, was seized upon by a people deprived of their rights.

the rights of man

Anon.

This song was first printed in Paddy’s Resource, a collection of revolutionary ballads, written by United Irish members and sympathizers, published in Belfast in 1795 and re-issued in 1796. An expanded edition was printed in Dublin in 1798 – Drennan’s ‘Wake of William Orr’ and the anonymous song ‘Edward’ come from this later edition. The book was published in Philadelphia in 1796 and New York in 1798. Many United Irish sympathisers emigrated or fled to the newly established United States during the 1790s.

I speak in candour, one night in slumber

My mind did wander near to Athlone,

The centre station of this Irish nation

Where a congregation unto me was shown.

Beyond my counting upon a mountain

Near to a fountain that clearly ran,

I feel to tremble, I’ll not dissemble

As they assembled for the rights of man.

All clad in green there I thought I seen

A virtuous Queen that was grave and old,

Saying Children dear, now do not fear

But come and hear what I will unfold.

This fertile country, near seven centuries

Since Strongbow’s entry upon our land,

Has been kept under with woes un-numbered

And always plundered of the rights of man.

My cause you chided, you so derided

When divided, alas you know.

All in disorder round Erin’s border

Strife, grief and murder has left you low.

Let each communion detest disunion,

In love and union join hand in hand.

And believe old Grania that proud Brittania

No more shall rob you of the rights of man.

Then I thought the crowd all spoke so loud

And straightway vowed to take her advice.

They seemed delighted and all united

Not to be frightened but to rejoice.

Her harp so pleasing she played amazing.

I still kept gazing but could not understand.

She sang most enchanting and most endearing

In words most cheering to the rights of man.

Throughout the azure sky I then did spy

A man for to fly and for to descend.

And straightway came down upon the ground

Where Erin round had her bosom friends.

His dazzling mitre and cross was brighter

Than stars by night or midday sun.

In accents rare then I do declare

He prayed success for the rights of man.

the swinish multitude

Anon.

Many of the songs in Paddy’s Resource were intended to be sung to well-known airs of the time. ‘The Swinish Multitude’ is written to the tune of ‘The Lass of Richmond Hill’. This song was the most popular work of Leonard MacNally (1752-1820), whose dramas and comic operas enjoyed considerable success. He was a member of the United Irishmen from the early 1790s and was friendly with most of its leaders, defending Napper Tandy, Tone, and Emmet at their respective trials. However, from at least 1794 he was also a paid agent of the government. His treachery was only revealed after his death when his son applied for the annuity paid in recognition of his father’s services.

Give me the man whose dauntless soul

Oppression’s threat defies,

And bids, tho’ tyrants thunder roll,

Thesun of freedomrise’

Who laughs at all the conjur’d storms,

State sorc’ry wakes around;

At pow’r in all his varying forms –

At title’s empty sound.

Give me the soul whose lustrious zeal,

Diffusing heaven born lights,

Instructs a people how to feel,

And how to gain their rights;

Who nobly scorning vain applause,

Or lucre’s fraudful plan,

Purely inlists for freedom’s cause –

The dearest cause of Man.

Hail ye friends united here,

In virtue’s sacred ties!

May you, like virtue’s self keep clear

Of pensioners and spies,

May you, By Bastiles ne’er appall’d

Seenature’s rightsrenew’d

Nor longer unaveng’d be called

‘the swinish multitude.’

Hail to the men where ‘er they be,

Whose kindling minds advance

In reason’s path, – All hail, yefree!

Of Holland, or of France!

She comes forall! Sweet Freedom comes!

To no one region bound;

The cause of Human Weal assumes,

And claims the globe around.

From vice to vice, while state craft flies,

May we its crimes pursue;

Pierce to the Source from whence they rise,

And hold them up to view.

This be our great, our steadfast task,

Resolv’d our strength to try;

This glory from our hearts we ask –

For thiswe daretodie.

the rising of the moon

John Keegan Casey (‘Leo’)

This, one of the rebellion’s most evocative ballads, conveys the undercover urgency of revolutionaries preparing to strike. It is therefore included in this section of the anthology.

Casey (1846-70) came from Milltown, Rathconrath, near Mullingar in County Westmeath. He was imprisoned for his Fenianism and he contributed to The Irish People, the Boston Pilot and the Shamrock. His other well-known song, the gentle ‘Máire, My Girl’ is in complete contrast.

‘Oh! then, tell me, Sean O’Farrell, tell me why you hurry so?’

‘Hush, mo bhuachaill, hush and listen,’ and his cheeks were all a-glow.

‘I bear orders from the Captain, get you ready quick and soon,

For the pikes must be together at the rising of the moon.’

‘Oh! then tell me, Sean O’Farrell, where the gathering is to be?’

‘In the old spot by the river, right well known to you and me.

One word more – for signal token whistle up the marching tune,

With your pike upon your shoulder, by the rising of the moon.’

Out from many a mud-wall cabin eyes were watching thro’ the night,

Many a manly breast was throbbing for the blessed warning light,

Murmurs passed along the valley like the banshee’s lonely croon,

And a thousand blades were flashing at the rising of the moon.

There beside the singing river that dark mass of men was seen,

Far above the shining weapons hung their own beloved green.

‘Death to every foe and traitor! Forward! Strike the marching tune,

And, hurrah, my boys for freedom! ‘tis the rising of the moon.’

Well they fought for poor old Ireland, and full bitter was their fate –

Oh! what glorious pride and sorrow fills the name of Ninety-Eight –

Yet, thank God, e’en still are beating hearts in manhoods burning noon

Who would follow in their footsteps at the rising of the moon!

united call

During the lead-up to the rebellion, the United Irishmen distributed a Proclamation. It was written by John Sheares and read:

Irishmen! your country is free, and you are about to be avenged. That vile Government which has so long and so cruelly oppressed you is no more! Some of its most atrocious monsters have already paid the forfeit of their lives, and the rest are in our hands. The national flag – the sacred green – is at this moment flying over the ruins of despotism; and that capital which, a few hours past, had witnessed the debauchery, the plots and crimes of your tyrants, is now the citadel of triumphant patriotism and virtue! Arise, the united sons of Ireland: arise, like a great and powerful people, determined to live free, or die! Arm yourselves by every means in your power, and rush like lions on your foes. Consider, that for every enemy you disarm, you arm a friend, and thus become doubly powerful. In the cause of liberty, inaction is cowardice, and the coward shall forfeit the property he has not the courage to protect. Let his arms be seized, and transferred to those gallant spirits who want and will use them. Yes, Irishmen! we swear by the Eternal Justice, in whose cause we fight, that the brave patriot who survives the present glorious struggle, and the family of him who has fallen, or shall fall hereafter in it, shall receive from the hands of a grateful nation an ample recompense out of that property which the crimes of our enemies have forfeited into our hands, and his name shall be inscribed on the great national record of Irish revolution, as a glorious example to posterity; but we likewise swear to punish robbers with death and infamy. We also swear, that we will never sheath the sword until every being in the country is restored to those equal rights which the God of nature has given to all men – until an order of things shall be established in which no superiority shall be acknowledged among the citizens ofErinbut that of virtue and talent.

Rouse all the energies of your souls; heed not the glare of a hired soldiery or aristocratic yeomanry; they cannot stand the vigorous shock of freemen; their trappings and arms shall soon be yours, and the detested Government of England, to which we vow eternal hatred, shall learn that the treasures it exhausts on its accoutered [sic] slaves, for the purpose of butchering Irishmen, shall but farther enable us to turn their swords on its devoted head.

Many of the military feel the love of liberty glow within their breasts, and have already joined the national standard. Receive, with open arms, such as shall follow so glorious an example; they can render signal service to the cause of freedom, and shall be rewarded according to their deserts. But, for the wretch who turns his sword against his native country, let the national vengeance be visited on him – let him find no quarter. Attack them, by day and by night, in every direction. Avail yourselves of the natural advantages of your country, which are innumerable, and with which you are better acquainted than they are. When you cannot attack them in fair force, constantly harass their rear and flanks, cut off their visions and magazines, and prevent them, as much as possible, from uniting their forces. Let whatever moment you cannot devote to fighting for your country be passed in learning how to fight for it, or preparing the means of war; for war, war alone, must occupy every mind and every hand in Ireland, until its soil be purged of all its enemies.

Vengeance! Irishmen! vengeance on your oppressors! Remember what thousands of your dearest friends have perished by their merciless orders! Remember their burnings, their rackings, their torturings, their military massacres, and their legal murders – remember Orr!

the bold belfast shoemaker

Anon.

The influence of French and American republicanism, religious discrimination and agrarian unrest affected a population that was increasing rapidly. Young men joined secret societies and heard about the probability of a French invasion. Some ‘listed in the train’, but relented later.

Come all you true born Irishmen, where-ever you may be

I hope you’ll pay attention and listen unto me.

I am a bold shoemaker, from Belfast Town I came

And to my great misfortune I listed in the train.

I had a fair young sweetheart, Jane Wilson was her name,

She said it grieved her to the heart to see me in the train.

She told me if I would desert to come and let her know,

She would dress me up in her own clothes that I might go to and fro.

We marched to Chapelizod like heroes stout and bold,

I’d be no more a slave to them, my officer I told,

For to work upon a Sunday with me did not agree

That was the very time, brave boys, I took my liberty.

When encamped at Tipperary, we soon got his command

For me and for my comrade bold, one night on guard to stand.

The night it was both wet and cold and so we did agree

And on that very night, brave boys, I took my liberty.

The night that I deserted I had no place to stay,

I went into a meadow and lay down in the hay.

It was not long that I lay there until I rose again,

And looking all around me I espied six of the train.

We had a bloody battle but soon I beat them all

And soon the dastard cowards for mercy loud did call.

Saying spare our lives brave Irewin and we will pray for thee,

By all that’s fair we will declare for you and liberty.

As for George Clarke of Carrick, I own he’s very mean,

For the sake of forty shillings he had me took again

They locked me in a strong room my sorrows to deplore,

With four on every window and six on every door.

I being close confined then I soon looked all around

I leaped out of the window and knocked four of them down,

The light horse and the train, my boys, they soon did follow me

But I kept my road before them and preserved my liberty.

I next joined Father Murphy as you will quickly hear

And many a battle did I fight with his brave Shelmaliers.

With four hundred of his croppy boys we beat great Lord Mountjoy

And at the battle of New Ross we made eight thousand fly.

I am a bold shoemaker and Irewin is my name

I could beat as many Orangemen as listed in a train;

I could beat as many Orangemen as could stand in a row

I would make them fly before me like an arrow from a bow.

Of Organizations

Volunteer companies were established in Belfast in February 1778. By December, they numbered 40,000. Lord Charlemont commanded the Northern Volunteers and the Duke of Leinster headed those in and around Dublin. Napper Tandy was a member of the Dublin Corps of Volunteers. In November 1779, a large body paraded in Dublin calling for Free Trade and in July of the following year Lord Charlemont and Henry Grattan reviewed them before they enacted a mock battle.

the dungannon convention

Thomas Davis

At Dungannon, County Tyrone, on 15 February 1782, 242 delegates from 148 Volunteer corps resolved that the ‘claims of any other than the King, Lords and Commons of Ireland to make laws to bind this kingdom is unconstitutional’. A resolution drafted by Henry Grattan began, ‘As men and as Irishmen, as Christians and as Protestants, we rejoice in the relaxation of the Penal Laws against our Roman Catholic fellow-subjects.’

Thomas Davis (1814-45) was a founder ofThe Nation, in 1842. Regarded as Ireland’s national poet in his time, he led the Young Ireland movement that his work inspired. His most famous ballads are ‘A Nation Once Again’ and ‘The West’s Asleep’.

The Church of Dungannon is full to the door,

And sabre and spur clash at times on the floor,

While helmet and shako are ranged all along,

Yet no book of devotion is seen in the throng.

In the front of the altar no minister stands,

But the crimson-clad chief of the warrior bands;

And though solemn the looks and the voices around,

You’d listen in vain for a litany’s sound.

Say! what do they hear in the temple of prayer?

Oh! why in the fold has the lion his lair?

Sad, wounded and wan was the face of our isle

By English oppression and falsehood and guile,

Yet when to invade it a foreign fleet steered

To guard it for England the North volunteered.

From the citizen-soldiers the foe fled aghast –

Still they stood to their guns when the danger had past,

For the voice of America came o’er the wave

Crying – Woe to the tyrant, and hope to the slave!

Indignation and shame through their regiments speed,

They have arms in their hands, and what more do they need?

O’er the green hills of Ulster their banners are spread,

The cities of Leinster resound to their tread,

The valleys of Munster with ardour are stirred,

And the plains of wild Connaught their bugles have heard.

A Protestant front rank and Catholic rere –

For – forbidden the arms of freemen to bear –

Yet foemen and friend are full sure, if need be,

The slave for his country will stand by the free.

By green flags supported, the Orange flags wave,

And the soldier half turns to unfetter the slave!

More honoured that Church of Dungannon is now

Than when at its altar Communicants bow;

More welcome to Heaven than anthem or prayer

Are the rights and the thoughts of the warriors there:

In the name of all Ireland the delegates swore:

‘We’ve suffered too long and we’ll suffer no more –

Unconquered by force, we were vanquished by fraud,

And now, in God’s temple, we vow unto God,

That never again shall the Englishman bind

His chains on our limbs, or his laws on our mind.’

The Church of Dungannon is empty once more –

No plumes on the altar, no clash on the floor,

But the councils of England are fluttered to see,

In the cause of their country, the Irish agree;

So they give as a boon what they dare not withhold,

And Ireland, a nation, leaps up as of old.

With a name, and a trade, and a flag of her own,

And an army to fight for the people and throng.

But woe worth the day if, to falsehood or fears,

She surrender the guns of her brave Volunteers.

In March 1782 at the Rotunda, Dublin, 150,000 Volunteers convened to claim Parliamentary reform, while Napper Tandy led artillery and be-decked horse past Parliament House. The guns bore scrolls that read ‘O Lord, open Thou our lips, and our mouths shall show forth Thy praise’. By 1784 Catholics were allowed join and Belfast Protestants actually collected for Roman Catholic church-building.

Other forces arose, including the agrarian Protestant Peep-o’-Day Boys (1784) and ‘Rightboys’ in Munster and Leinster (1785). Initially in Armagh, later all over Ulster, peasant Ulster Catholics formed a defence organization (September 1785). It was the equivalent to the Peep-o’-Day Boys. Later, midland Catholic peasants took on the name Defenders, as they perpetrated actions against clergy and tithe proctors.

In March 1787 the Tumultuous Risings Act (The Whiteboy Act) introduced provisions of the British Riot Act to Ireland. It was directed against people who administered or accepted illegal oaths or who hampered in any way the collection of tithes. The Volunteer movement waned and its support had dwindled completely by the end of 1790.

On 1 April 1791, in Belfast, Samuel McTier and others decided to form an association that would unite all Irishmen ‘to pledge themselves to our country’. In October of the same year, Robert Simms joined McTier in formally founding the Society of United Irishmen. Initially, its members were mainly Ulster Presbyterians and liberal Protestants seeking Parliamentary reform and removal of religious grievance.

early frustrations

The difficulties experienced in setting up any organization are evident in memoranda and entries in Wolfe Tone’s diary. John Egan (c.1750-1810) was a barrister, a member of Parliament and a duellist who did not get on with John Philpot Curran.

Memo. 21 June 1789. The committee for drawing up the address to the Chancellor, being headed by Egan and Tom Fitzgerald, were said by Curran to be more like a committee for drawing a waggon than for drawing up an address.

1791

July 14th.I sent down to Belfast, resolutions suited to this day, and reduced to three heads. 1st, That English influence in Ireland was the great grievance of the country. 2nd, That the most effectual way to oppose it was by a reform in Parliament. 3rd, That no reform could be just or efficacious which did not include the Catholics, which last opinion, however, in concession to prejudices, was rather insinuated than asserted.

I am, this day, July 17, 1791 [sic], informed that the last question was lost. If so, my present impression is to become a red-hot Catholic; seeing that in the party, apparently, and perhaps really, most anxious for reform, it is rather a monopoly than an extension of liberty, which is their object, contrary to all justice and expediency.

October 11th.Arrived at Belfast late, and was introduced to Digges, but no material conversation. Bonfires, illuminations, firing twenty-one guns, Volunteers, &c.

October 12th.Introduced to McTier and Sinclair. A meeting between, Mc Tier, Macabe, and me. Mode of doing business by a Secret Committee, who are not known or suspected of co-operating, but who, in fact, direct the movements of Belfast. Much conversation about the Catholics, and their committee, &c., of which they know wonderfully little atBlefescu[nickname for Belfast]. Settled to dine with the Secret Committee at Drew’s, on Saturday, when the resolutions, &c., of the United Irish will be submitted. Sent them off, and sat down to new model the former copy. Very curious to see how the thermometer of Blefescu has risen, as to politics. Passages in the first copy, which were three months ago esteemed too hazardous to propose, are now found too tame. Those taken out, and replaced by other and better ones. Sinclair came in; read and approved the resolutions, as new modelled. Russell gave him a mighty pretty history of the Roman Catholic Committee, and his own negotiations. Christened RussellP.P. Clerk of this Parish. Sinclair asked us to dine and meet Digges, which we acceded to with great affability. Went to Sinclair, and dined. A great deal of general politics and wine. Paine’s book, the Koran of Blefescu. History of the Down and Antrim elections. The Reeve of the shire a semi-Whig. P.P. very drunk. Home; bed.

October 13th.Much good jesting in bed, at the expense of P.P. Laughed myself into good humour. Rose. Breakfast. Dr McDonnell. Much conversation regarding Digges. Went to meet Neilson; read over the resolutions with him, which he approved.

The first meeting of the movement’s Dublin branch was held in the Eagle Tavern, Eustace Street, on 9 November. Napper Tandy was its secretary. Wolfe Tone and Thomas Russell were co-founders.

Following the outbreak of war between England and France in Feb-ruary 1793, the introduction of repressive measures led to its becoming an underground movement that sought French assistance in terminating British rule in Ireland.

declaration and resolutions of the society of united irishmen of belfast

In the present era of reform, when unjust governments are falling in every quarter of Europe; when religious persecution is compelled to abjure her tyranny over conscience; when the rights of man are ascertained in theory, and that theory substantiated by practice; when antiquity can no longer defend absurd and oppressive forms, against the common sense and common interests of mankind; when all government is acknowledged to originate from the people and to be so far only obligatory as it protects their rights and promotes their welfare: We think it our duty, as Irishmen, to come forward, and state what we feel to be our heavy grievance, and what we know to be its effectual remedy.we have no national government; we are ruled by Englishmen, and the servants of Englishmen, whose object is the interest of another country, whose instrument is corruption, and whose strength is the weakness of Ireland; and these men have the whole of the power and patronage of the country, as means to seduce and to subdue the honesty and the spirit of her representatives in the legislature. Such an extrinsic power, acting with uniform force in a direction too frequently opposite to the true line of our obvious interest, can be resisted with effect solely byunanimity, decision, and spirit in the people; qualities which may be exerted most legally, constitutionally, and efficaciously, by that great measure essential to the prosperity and freedom of Ireland.an equal representation of all the people in parliament. We do not here mention as grievances, the rejection of a place-bill, of a pension-bill, of a responsibility-bill, the sale of Peerages in one House, the corruption publicly avowed in the other, nor the notorious infamy of borough traffic between both; not that we are insensible of their enormity, but that we consider them as but symptoms of that mortal disease which corrodes the vitals of our Constitution, and leaves to the people, in their own Government, but the shadow of a name.

Impressed with these sentiments, we have agreed to form an association, to be called ‘the society of united irishmen:’ And we do pledge ourselves to our country, and mutually to each other, that we will steadily support, and endeavor, by all due means, to carry into effect, the following resolutions:

First, Resolved, That the weight of English influence in the Government of this country is so great, as to require a cordial union ofall the people of ireland, to maintain that balance which is essential to the preservation of our liberties, and the extension of our commerce.

Second,That the sole constitutional mode by which this influence can be opposed, is by a complete and radical reform of the representation of the people in Parliament.

Third,That no reform is practicable, efficacious, or just, which shall not include Irishmen of everyreligiouspersuasion.

Satisfied, as we are, that the intestine divisions among Irishmen have too often given encouragement and impunity to profligate, audacious, and corrupt Administrations, in measures which, but for these divisions, they durst not have attempted; we submit our resolutions to the nation, as the basis of our political faith.

We have now gone to what we conceive to be the remedy. With a Parliament thus reformed, every thing is easy; without it, nothing can be done: and we do call on and most earnestly exhort our countrymen in general to follow our example, and to form similar societies in every quarter of the kingdom, for the promotion of constitutional knowledge, the abolition of bigotry in religion and politics, and the equal distribution of the rights of man through all sects and denominations of Irishmen. The people, when thus collected, will feel their own weight, and secure that power which theory has already admitted as their portion, and to which, if they be not aroused by their present provocations to vindicate it, they deserve to forfeit their pretensionsfor ever.

Theobald Wolfe Tone, Belfast, October 1791

minute

A 1792 entry in theProceedings of the Society of United Irishmen of Dublin:

It was not till very lately that the part of the nation which is truly colonial, reflected that though their ancestors had been victorious, they themselves were now included in the general subjection; subduing only to be subdued, and trampled upon by Britain as a servile dependency. When therefore the Protestants began to suffer what the Catholics had suffered; when from serving as the instruments they were made themselves the objects of foreign domination, then they became conscious they had a country – Ireland. They resisted British dominion, renounced colonial subserviency and … asserted the exclusive jurisdiction of this Island.

the liberty tree

Anon.

Taking example from the French Revolution, a custom among United Irishmen of planting a ‘Liberty Tree’ began.

It was the year of ’93,

The French did plant an olive tree

The symbol of great liberty

And the people danced around it.

‘Oh was not I telling you,’

The French declared courageously

‘That Equality, Freedom and Fraternity

Would be the cry of every nation.’

In ’94 a new campaign,

The tools of darkness did maintain

Gall’s brave sons did form a league

And their foes they were dumb-founded.

They gave to Flanders liberty

And all its people they set free

The Dutch and Austrians home did flee

And the Dukes they were confounded.

Behold may all of Human-kind,

Emancipated with the French combine

May laurels green all on them shine

And their sons and daughters long wear them.

May every tyrant shake with dread

And tremble for their guilty head

May the Fleur-de-Lis in dust be laid

And they no longer wear them.

For Church and State in close embrace

Is the burden of the Human Race

And people tell you to your face

That long you will repent it.

For Kings in power and preaching drones

Are the cause of all your heavy groans

Down from your pulpits, down from your thrones

You will tumble unlamented.

‘Oh was not I telling you,’

The French declared courageously,

‘That Equality, Freedom and Fraternity

Would be the cry of every nation.’

the tree of liberty

Anon

Out of chronological order , it is worth giving the Orange Order’s (see below) riposte here. It refers to the Sheares Brothers, of whose execution we will learn later.

J.B. Esqu. of Lodge No. 471 included the poem in A Collection of Loyal Songs.

Sons of Hibernia, attend to my song,

Of a tree call’d th’Orange, it’s beauteous and strong;

‘Twas planted by William, immortal is he!

May all Orange brothers live loyal and free.

Derry down, down, traitors bow down.

Around this fair trunk we like ivy will cling,

And fight for our honour, our country, and king;

In the shade of this Orange none e’er shall recline

Who with murd’rous Frenchmen have dar’d to combine.

Derry down, down, Frenchmen bow down.

Hordes of barbarians, Lord Ned [Edward Fitzgerald] in the van,

This tree to destroy laid an infamous plan;

Their schemes prov’d abortive, tho’ written in blood,

Nor their pikes, nor their scythes could pierce Orange wood.

Derry down, down, rebels bow down.

While our brave Irish tars protect us by sea,

From false perjured traitors this island we’ll free;

Priest [Murphy’s] war-vestment they’ll find of no use,

Wherever we meet them they’re sure to get goose.

Derry down, down, priestcraft bow down.

Hundreds they’ve burn’d of each sex, young and old,

From Heaven the order – by priests they were told;

No longer we’ll trust them, no more to betray,

But chase from our bosoms those vipers away.

Derry down, down, serpents bow down.

Rouse then, my brothers, and heed not their swearing,

Absolv’d they have been for deeds past all bearing;

Mercy’s misplac’d, when to murderers granted,

For our lands and our lives those wretches long panted.

Derry down, down, reptiles bow down.

Then charge high your glasses, and drink our Great Cause,

Our blest Constitution, our King, and our Laws;

May all lurking traitors, wherever they be

Make the exit of Sheares, and Erin be free.

Derry down, down, traitors bow down.

orange order

After a fight between Protestant Peep-o’-Day Boys and Catholic Defenders at The Diamond, Loughgall, County Armagh, in September 1795, an Orange Society was formed. Its members perpetrated atrocities against Catholics, driving many of them out of Ulster. James Sloan of Loughgall became the first Grand Master of the Orange Order that emerged later, while the first Loyal Orange Lodge was founded in Dyan, County Tyrone. Its strength quickly leaped to an estimated 100,000. Its oath ran as follows:

I, A.B., do solemnly and sincerely, in the presence of God, profess, testify, and declare that I do believe that in the Sacrament of the Lord’s Supper there is not any transubstantiation of the elements of bread and wine into the body and blood of Christ, at or after the consecration thereof by any person whatsoever; and that the invocation or adoration of the Virgin Mary, or any other saint, and the sacrifice of the Mass, as they are now used in the Church of Rome, are superstitious and idolatrous. And I do solemnly in the presence of God profess, testify, and declare that I make this declaration and every part thereof in the plain and ordinary sense of the words read unto me as they are commonly understood by the English Protestants without any evasion, equivocation, or mental reservation whatsoever, and without any dispensation already granted me for this purpose by the Pope or any other authority or person whatsoever, or without any hope of any such dispensation from any person or authority whatsoever, or without thinking that I am or can be acquitted before God and man, or absolved of this declaration, or any part thereof, although the Pope or any other person or persons, or power whatsoever, should dispense with or annul the same, or declare that it was null and void from the beginning.

Blessedly more humourous is a form of toast associated with social Orange gatherings, as outlined by Sir Jonah Barrington:

the loyal toast

Barrington (1760-1834) was a Judge to the Admiralty in 1798. His books, Personal Sketches of His Own Times and The Rise and Fall of the Irish Nation illuminate the period. He appeared to oppose the Act of Union, and consequently enjoyed the confidence of prominent United Irishmen. Some, however, suspected him of informing and subsequent self-advancement gives credence to the theory.

Barrington’s wife, the inquisitive daughter of a silk merchant, dressed in her father’s finest materials and sat in her St Stephen’s Green window where she could see Lady Clonmel in her Harcourt Street home. Lord Clonmel (see Sham Squire) complained and Sir Jonah had the window blocked up. Commentators have suggested that his deference to Clonmel supported the theory of his being less than patriotic.

The glorious, pious and immortal memory of the great and good King William – not forgetting Oliver Cromwell, who assisted in redeeming us from Popery, slavery, arbitrary power, brass monkey and wooden shoes.

May we never want a Williamite to kick the **** of a Jacobite! and a **** for the Bishop of Cork! And he that won’t drink this, whether he be priest, bishop, deacon, bellows-blower, grave-digger, or any other of the fraternity of the clergy; may a north wind blow him to the south; a west wind blow him to the east! May he have a dark night – a lee shore – a rank storm – and a leaky vessel, to carry him over the river Styx! May the dog Cerebus make a meal of his rump, and Pluto a snuff-box of his skull; and may the devil jump down his throat with a red-hot harrow, with every pin to tear a gut, and blow him with a clean carcass to hell! Amen!

Sir Jonah considered the toast a mere ‘excuse for getting loyally drunk as often as possible’. He added a footnote:

Could his majesty, King William, learn in the other world that he has been the cause of more broken heads and drunken men, since his departure, than all his predecessors, he must be the proudest ghost and most conceited skeleton that ever entered the gardens of Elysium.

Another popular version goes:

Here’s to good King William III, of pious, glorious and immortal memory, who saved us from slaves and slavery, knaves and knavery, rogues and roguery – brass money and wooden shoes. And all who deny this toast: may they be slammed, crammed and jammed into the great muzzle of the gun of Athlone, and blown on the hob of hell, where he’ll be kept roasting for all eternity, the devil basting him with melted bishops and his imps pelting him with priests. And may the gun fired into the Pope’s belly, and the Pope into the devil’s belly and the devil into hell and the door locked tight and the key safe forever in an Orangeman’s pocket.

letter from a soldier

At the ‘Battle of the Diamond’ (above) a group of Protestants known as The Wreckers came from Portadown and Rich Hill to Loughgall. There were skirmishes and house-burnings for two days. The Wreckers were leaving on Monday 21 September when a party of Defenders from Cavan, Tyrone and Monaghan arrived in the village and broke the windows of a Protestant home. An eye-witness described the scene that followed.

Down swept the Protestant Boys from the hill, shooting as they came, and with their swords and bayonets they spread the wildest confusion, and made terrible slaughter among the papists on whose side men, women and children were now huddled up. All that followed was a havoc – a cold-blooded and brutal massacre … Everyone fled, and you could see men dragging their wives and brothers, pulling their wounded sisters after them, leaving their fathers dead on the ground.

Years later, on 19 October 1839,The Globenewspaper published a letter with a Newmarket address.

Sir,

As a cornet in the 24th Light Dragoons, then commanded by the late Lord Wm. Bentinck, I accompanied the regiment to Ireland in 1795. We disembarked at Dublin, and proceeded to Clonmel, from whence, in the autumn of that year, a squadron was suddenly ordered in consequence of the disturbed state of the country, to proceed to Armagh. To this squadron I was attached. Very shortly after our arrival the Caithness Highlanders, commanded by Sir Thomas, then Major, Molyneux, relieved a regiment of Irish militia stationed at Armagh. The County of Armagh was then in a very disturbed state, arising from the feuds between the Protestant and Catholic population, unhappily too much encouraged by the dominant party; but of these religious dissensions the Orange Societies, fostered and encouraged by the father of the present Colonel Verner, had their origin. The avowed object of the Protestant party was to drive the Catholics out of the country.

In the course of the following year the whole regiment took up its quarters at Armagh and the neighbourhood. It so happened that I commanded a detachment of the regiment at Loughall, in the very centre of that part of the County of Armagh where the disturbance most prevailed, and not very far distant from the spot where the Battle of the Diamond took place. There I remained several months, and during that period I had witnessed the excesses committed by the Orange party, who now began to form themselves into lodges, and the dreadful persecutions to which the Catholic inhabitants were subjected. Night after night I have seen the sackings and burnings of the dwellings of these poor people. And notwithstanding the active exertions of the Sovereign of Armagh, under whose orders the military frequently scoured the country, our movements were so closely watched that these depredations were continued almost with impunity. When we arrived at a burning dwelling the perpetrators had fled across the country, and their course could only be traced by the fires they left in their progress.

Many of the Orangemen, however, notwithstanding the secrecy with which they conducted their proceedings, were discovered on private information, and brought to trial. But most of them, through the influence of their party, escaped, either altogether or with slight punishment.

In one case, a most atrocious one, a man had been sentenced to death; this man’s sentence was respited, and I well remember the whole country round being illuminated with bonfires in manifestation of the joy of the Orangemen on that occasion. The result was an increased measure of persecution; many poor families were driven from their homes, their dwellings burnt, and themselves obliged to take shelter among their Catholic brethren in Connaught. These outrages were not unfrequently accompanied with bloodshed.

I may mention one of these dreadful scenes, of which I was myself an eye-witness, during our nightly patrol. We had already reached a heap of ruins, when a shot was heard, apparently about a quarter of a mile from the fire. On proceeding to the spot we discovered a dying man, whom the miscreants had shot in his house in their retreat from the fire. They had fired through the window in to the room where the man was sitting with his family. The poor fellow died a few minutes after our arrival.

It is impossible for me to describe, at this distance of time, the horrors and atrocities I witnessed during that period, which Major Molyneux describes as being without disturbance. Indeed, such was the state of the County of Armagh, that our regiment was quartered in the different mansions of the gentry of the county.

Mr O’Sullivan states that the Battle of the Diamond broke the neck of the Irish rebellion. It so happened that I was quartered at Market-hill, the house of Lord Gosford, when the rebellion of 1798 broke out, and I can positively assert, and I appeal to the history of those times, that the Catholics had no share in the disturbances of that period, at least in the North of Ireland.

The rebellion, it is well known, was brought out by the United Irishmen, who were none of them Catholics, and not one of the leaders who were convicted and executed in the Counties of Down and Antrim were of that creed. On the contrary, when the troops assembled at Castledawson, under General Knox, a most active magistrate, a resident in that town, Mr Shiel, who with his sons were in a corps of yeomanry, and took a most decided part in the suppression of the rebellion, were Roman Catholics.

‘AN OLD OFFICER OF CAVALRY’

the orange yeomanry of ’98

Anon.

The History Of Orangeism by M.P. (Dublin & Glasgow 1882) tells of the origin and rise of the Orange Order. In one section, it comments on poems and songs sung at Orange meetings ‘after the mysteries of the lodge have been disclosed’. Having offered the following sample – written after the rebellion – M.P. adds, ‘Little wonder that Orange outrages follow fast upon Orange Lodge meetings, where such blasphemous productions, rendered more exciting by deep potations, are permitted to arouse the religious frenzy of ignorant fanatics.’ Ulster yeomanry units were often recruited from Orange Lodges.

I am an humble Orangeman –

My father he was one;

The mantle which the sire once wore