0,84 €

Mehr erfahren.

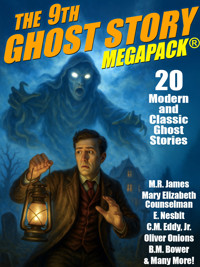

- Herausgeber: Wildside Press

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

The 9th Ghost Story MEGAPACK® presents 20 classic and modern ghost stories, including many rare and seldon-seen tales. This may be the ninth volume in the series, but the chills and ghostly happenings are as strong as ever. Included in this volume are:

RESURGAM, by Rina Ramsay

FOUR DREAMS OF GRAM PERKINS, by Ruth Sawyer

THE HAUNTED DRAGOON, by A.T. Quiller-Couch

THE OPEN DOOR, by Mrs. Oliphant

THE GHOST THAT FAILED, by Desmond Coke

THE GHOST WHO WAS AFRAID OF BEING BAGGED, by Lal Behari Dey

NIGHT COURT, by Mary Elizabeth Counselman

THE GHOST FARM, by Susan Andrews Rice

A PHANTOM OF THE MINES, by Robert Howard Syms

THE GHOST IN THE RED SHIRT, by B.M. Bower

THE ASH-TREE, by M.R. James

THE GHOST REDIVIVUS, by Matilda Betham-Edwards

THE HAUNTED INHERITANCE, by E. Nesbit

CELIA AND THE GHOST, by Barry Pain

THE GHOST, by Oliver Onions

SAW THE GHOST SHIP, by A Georgia Traveler

THE GHOST-EATER, by C.M. Eddy, Jr.

THE YELLOW CAT, by Michael Joseph

THE GHOST OF DR. HARRIS, by Nathaniel Hawthorne

THE PHANTOM RIDER, by Otis Adelbert Kline

If you enjoy this volume of our best-selling MEGAPACK® series, check out the more than 400 others. Search your favorite ebook store for

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 487

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Ähnliche

Table of Contents

COPYRIGHT INFO

INTRODUCTION

ABOUT THE SERIES

RESURGAM, by Rina Ramsay

FOUR DREAMS OF GRAM PERKINS, by Ruth Sawyer

THE HAUNTED DRAGOON, by A.T. Quiller-Couch

THE OPEN DOOR, by Mrs. Oliphant

THE GHOST THAT FAILED, by Desmond Coke

THE GHOST WHO WAS AFRAID OF BEING BAGGED, by Lal Behari Dey

NIGHT COURT, by Mary Elizabeth Counselman

THE GHOST FARM, by Susan Andrews Rice

A PHANTOM OF THE MINES, by Robert Howard Syms

THE GHOST IN THE RED SHIRT, by B.M. Bower

THE ASH-TREE, by M.R. James

THE GHOST REDIVIVUS, by Matilda Betham-Edwards

THE HAUNTED INHERITANCE, by E. Nesbit

CELIA AND THE GHOST, by Barry Pain

THE GHOST, by Oliver Onions

SAW THE GHOST SHIP, by A Georgia Traveler

THE GHOST-EATER, by C.M. Eddy, Jr.

THE YELLOW CAT, by Michael Joseph

THE GHOST OF DR. HARRIS, by Nathaniel Hawthorne

THE PHANTOM RIDER, by Otis Adelbert Kline

Wildside Press’s MEGAPACK® Ebook Series

COPYRIGHT INFO

The 9th Ghost Story MEGAPACK® is copyright © 2025 by Wildside Press, LLC.

The MEGAPACK® ebook series name is a registered trademark of Wildside Press, LLC

All rights reserved.

Published by Wildside Press LLC.

wildsidepress.com

INTRODUCTION

We must really ghost stories here at Wildside Press—we have now now reached our ninth volume in this series. (And our Macabre MEGAPACK® series also has quite a few phantoms lurking it its volumes, too.)

When you think about it, few other genres are as enduring as the supernatural. From the earliest oral traditions to the flickering screens of today, ghost stories have maintained their grip on the human imagination with remarkable persistence. The tales collected in this volume represent a particularly rich period in supernatural fiction, spanning from the early 1800s through the mid-1900s—an era that witnessed the genre’s golden age.

This period saw ghost stories evolve from Gothic horror’s melodramatic origins into more psychologically sophisticated narratives. The Victorian era, with its fascination with death, mourning rituals, and the emerging spiritualist movement, proved especially fertile ground for spectral fiction. Authors like Sheridan Le Fanu, M.R. James, and Henry James elevated the ghost story from mere sensationalism to literary art, crafting tales that explored grief, guilt, and the permeable boundaries between past and present.

The early twentieth century brought new dimensions to supernatural fiction, as writers began incorporating modern psychology and the uncertainties of a rapidly changing world. These stories often reflected contemporary anxieties about technology, war, and social upheaval, while maintaining the timeless appeal of the unexplained.

The twenty tales gathered here represent the breadth and depth of this remarkable literary tradition, offering everything from spine-tingling Gothic chillers to subtle psychological hauntings. Each story reminds us why ghosts have never truly gone out of fashion—because the best supernatural fiction speaks to something eternal in the human experience: our fascination with death, memory, and the mysteries that lie beyond the veil.

Enjoy!

—John Betancourt

Publisher, Wildside Press LLC

wildsidepress.com

ABOUT THE SERIES

Over the last few years, our MEGAPACK® ebook series has grown to be our most popular endeavor. (Maybe it helps that we sometimes offer them as premiums to our mailing list!) One question we keep getting asked is, “Who’s the editor?”

The MEGAPACK® ebook series (except where specifically credited) are a group effort. Everyone at Wildside works on them. This has included John Betancourt (me), Carla Coupe, Steve Coupe, Shawn Garrett, Helen McGee, Bonner Menking, Sam Cooper, and many of Wildside’s authors…who often suggest stories to include (and not just their own!)

RECOMMEND A FAVORITE STORY?

Do you know a great classic science fiction story, or have a favorite author whom you believe is perfect for the MEGAPACK® ebook series? We’d love your suggestions! You can email the publisher at [email protected].

Note: we only consider stories that have already been professionally published. This is not a market for new works…the one in this issue being a notable exception.

TYPOS

Unfortunately, as hard as we try, a few typos do slip through. We update our ebooks periodically, so make sure you have the current version (or download a fresh copy if it’s been sitting in your ebook reader for months.) It may have already been updated.

If you spot a new typo, please let us know. We’ll fix it for everyone. You can email the publisher at [email protected].

RESURGAM,by Rina Ramsay

Originally published in The Strand Magazine, August 1915.

CHAPTER I

The London parson had taken a night off to run down and preach for Stackhouse.

He liked the change. It was like dipping into another world to slip out of his own restless parish into the utterly different atmosphere of this quiet country town. It had struck him most in the pulpit, when the lights went up on the sleepy congregation and he gave out a concluding hymn. How alike they were; all one pattern, all known to each other, all leading the same staid, ordinary lives. What a blessed tonic, his brief sojourn in this placid community.

He puffed out his chest, drinking in the soft night air that was so good to swallow. He was a big man and burly, and the narrow pavement would hardly hold the three of them abreast, so he was walking between the other two down the middle of the darkened street. They passed various worshippers in the glimmer—families, friends, and sweethearts—all of them pausing to say good-night. Such a peaceable little town and so friendly! It struck him again as comical that it should have been Stackhouse and not himself who had had a nervous breakdown last summer.

He burst out chuckling, and then, on the point of sharing his amusement at such an anomaly, was discreet. Those highly strung individuals were so touchy. And Stackhouse did not seem in the humour for chaffing. His mouth was set in an odd line of strained endurance and he hardly spoke. His long, lean, ascetic figure had something monkish about it as he stalked along in his cassock. His eyes were staring into the gloom ahead.

Mrs. Stackhouse, on the other side, was making up for her husband’s silence. Robinson had had no idea she was such a chattering woman. It began to annoy him. It seemed to him that there was a suggestion of hysteria in her incessant prattle.

Near the vicarage gate they overtook a woman of the charwoman class, and the vicar’s wife hailed her with the usual salutation and asked why Bessy had missed Sunday-school. The woman unlatched the gate for them. She had a small child with her, and spoke for its benefit in a mincing tone.

“Bessy’s bin a very bad girl, ma’am. She’s been telling lies.”

“Oh, dear!” said Mrs. Stackhouse, properly scandalized.

“Yes, ma’am; the young monkey! She will have it her lady, as used to, sat with her on Sunday night.”

“Oh!” said Mrs. Stackhouse again, but swiftly. “Nonsense, nonsense!”

She whisked through the gate, which clanged after them, leaving the woman outside with the infant, unadmonished, hanging to her skirt with a finger in its mouth. In the light of the hall lamp she glanced furtively at her husband.

“My dear boy!” she said, hurriedly, almost wildly; “a child of four—!”

Stackhouse dropped his eyes from hers, and lifted his hand with a curious gesture as if he were wiping the sweat from his brow.

Inside the house Mrs. Stackhouse fled to the kitchen to hurry that uncomfortable meal called supper, and the two men waited a minute or two by the study fire.

“Awfully good of you to come down, Robinson,” said the vicar. He spoke in a strained voice; there was something in it that sounded like expectation, like some faint hope; but the Londoner, for all his alertness, had not a clue. He noticed, however, that his host’s knuckles gleamed white as he gripped hard on the edge of the chimney-piece. These long, weedy men had no stamina, physical or nervous. It must have been his temperament, certainly not his surroundings, that had made Stackhouse go to pieces.

“Good of you to ask me,” he said, politely. “I love this quiet place. Such a contrast to my parish! You should see us up there, how crowded, quarrelling and fighting. I’m afraid that sea voyage didn’t set you up altogether?”

“I thought it had, though,” said Stackhouse, abruptly. “When I came back—”

He shut his mouth suddenly in the middle of the sentence but looked hard at his fellow-priest. In his look was wistfulness, and an imminent despair.

“I’d like to ask you something,” he said, “but—I dare not.” He let go the chimney-piece and led the way into the dining-room, where Mrs. Stackhouse was calling them. She was too anxiously hospitable for comfort, bouncing up and down behind her coffee-pot, fussing about the food, and rattling on feverishly; but keeping, the visitor could see, a distracted eye on her husband. There was not much coherence in her prattle, and sometimes she lost the thread of it and looked for a minute helpless. Only at such disconcerting moments could the Londoner, coming to the rescue, get a word in.

Why would the woman insist on talking, and what was she afraid of? Some outbreak of nerves on the part of the silent man? Was it pure hysteria on her part, or was she trying to cover some private fear?

He seized the first opportunity to take his share in the conversation, mildly humorous, but conscious all the while of the peculiar strain in the atmosphere. And then, incidentally, he remembered something.

“By the way,” he said, “you lucky people, you know all your congregation. Who is the lady who sat in the side aisle alone in the seat next the pillar? A singularly interesting face—”

Mrs. Stackhouse started violently.

“Wh—what was she like?” she asked.

“Rather eager and sad,” said Robinson, reflecting, “but quite a girl. She had a pointed chin, and dark hair, I think, and large, dark eyes—penetrating eyes; and she wore some kind of glittering jewel hung round her neck. It was her troubled expression that struck me first—”

He broke off astonished. For Stackhouse had stood up and was staring at him, gripping the table, leaning over. His look was half incredulous, half unspeakable relief.

“Then,” he said, in a choked voice, “you, too, saw her. Thank Heaven! I am not mad.”

Mrs. Stackhouse hid her face suddenly in her hands and burst into an uncontrollable fit of crying.

The visitor looked from one to the other in real alarm. He could see nothing in his harmless remark to affect them so deeply, or to relax, as it seemed, an intolerable strain.

“I’m afraid—” he began.

Mrs. Stackhouse sat up and smiled.

“But we are so thankful to you,” she said, still sobbing. “Oh, you can’t imagine what a relief it is! You’re an independent witness—unprejudiced—and you saw her. Oh, you don’t know what it means to us. We were both so terrified that his mind was going—”

“Still,” said the Londoner, puzzled, “I can’t see how my mentioning that young lady—”

She interrupted him. Something like awe hushed her excited voice.

“The girl you saw in church,” she said, “died last year.”

“Impossible!” said Robinson.

Stackhouse—who was with difficulty controlling a nervous tremor that shook him from head to foot, but whose voice was steady—moved to the door.

“Let us go back to the study,” he said, “and talk it over.”

His whole manner was changed as he stood on the hearthrug looking down on his guest and his wife. He had lost the pathetic hesitation that Robinson had noticed in him that night and recovered something of his old bearing of priestly pomp. “Most of us believe in the unseen,” he pronounced; “but to find what belongs to the other world made visible—brought so close—is a dreadful shock. My wife thought it must be an hallucination; she thought I was going mad—and I, too, grew horribly afraid. You see, I had had that nervous breakdown before, and the doctors sent me away for six months. It looked as if the prescription had failed. We thought that my breakdown must have been the warning of a mental collapse. We—I can’t tell you, Robinson, what we suffered. And yet I saw that poor girl, night after night, so plainly—”

“She was such a nice girl!” broke in Mrs. Stackhouse, in her gasping treble; “and such a help in the parish. We liked her so much. And, of course, we were getting no letters—the doctors had forbidden it; we had heard nothing whatever till we came home, and they told us she had committed suicide soon after we went away. I thought the shock of it had been too much for George. No wonder—such a good girl, Mr. Robinson. She—she used to sit in that seat with the schoolchildren to keep them quiet. No one could have dreamt she could do anything so wicked—”

“Do you mean,” said Robinson, bluntly, “that I saw a ghost?”

Stackhouse bent his head. His wife shivered suddenly as if she had not till then fully realized what it meant. Her mind had been so possessed by fear for the sanity of her husband; her relief had been too intense.

“I—suppose so,” she said, in an awe-stricken whisper.

There followed a short pause; no sound but the fire crackling and the night wind sighing a little outside the room. Mrs. Stackhouse drew in nearer the fender as if she were very cold and made a little gasp in her throat. The Londoner, looking from one to the other with his kindly, humorous glance, began to talk common sense.

“Of course it’s a mistake,” he said. “The girl I saw in church tonight was real. It can only be some chance likeness—perhaps a relation—”

Stackhouse shook his head.

“No,” he said. “There’s no one like her. Poor girl, poor girl; her spirit cannot rest. God forgive me, there must have been something deadly wrong in my teaching, since it could not keep her from such a dreadful act. Is it strange that she looks reproachful?”

“But haven’t you made enquiries?”

“We have not dared to speak of it to a soul!” cried Mrs. Stackhouse. “They would all have believed—as I did—that George was going mad. Oh, can’t you see the horrible difficulty? And then—”

“I am not going to have my church made a public show for the rabble,” said Stackhouse, violently. “I won’t have that desecration! Can’t you see them crowding here in their thousands, staring, scoffing, profaning a holy place? The newspapers would seize on the tale in a moment! For Heaven’s sake, man, hold your tongue.” He stopped, and again that nervous tremor took him.

“Do you mind telling me the circumstances? Who was this girl?” said the Londoner curious, but stoutly incredulous. “It certainly wasn’t the face of a suicide that I saw—”

“No. It’s incomprehensible,” said Stackhouse, trying to recover a sort of calm. “She was the last person in the world, you would have said. How little we creatures know! She lived with her uncle, a solicitor here, and kept house for him. The uncle is my churchwarden. She was going out shortly to India to be married. There was nothing to worry her.”

“Poor little Kitty!” said Mrs. Stackhouse, in a sobbing breath. “If only we had been there—”

“Yes, she might have confided in us,” said Stackhouse. “But the priest I left in charge here was a young man, lately ordained; shy, and not observant. And nobody had noticed anything strange about her. Only her uncle said at the inquest that he was afraid she had been a little scared at the idea of her approaching marriage. She had lived in this place all her life, and it was a wrench to leave it; and she had not seen the man for five years. He was afraid she must have been brooding in secret and dreading the journey; and he blamed himself for thinking it only natural a girl should be fluttered at the prospect of such a tremendous step. Poor man, he must have been terribly distressed. One of the jury told me that if they could have found any possible excuse they would have brought it in misadventure, if only to spare his feelings—”

“But she went down to the chemist herself and bought the stuff,” broke in Mrs. Stackhouse. “She told him she wanted it for an old dog that had been run over; she signed the poison book and asked him particularly if it would be painless. Of course, knowing her as he did, he never dreamt—”

“And the dog?” said Robinson.

“There was no dog,” said Stackhouse. “No one in the house had heard of it. She locked her door as usual at night—she had done it ever since an alarm of burglars in the house years ago; and when they got frightened in the morning and burst it in she was found dead in bed. She had drunk the poison in the lemonade she took up with her every night.”

“And they buried her with a mutilated service!” said Mrs. Stackhouse, shuddering.

“Poor girl!” said Stackhouse and turned away his head.

The London parson broke the distressing silence.

“A very sad case,” he said; “but aren’t you letting it overcome your judgment? Why in this case beyond all others should her unhappy spirit be allowed to haunt the church? I dare say it is just what a miserable soul would wish, sorrowful, self-tormenting—if uncontrolled. But I see no reason why it should be permitted. And assuming it could be, I’m curious to know why she should appear to you and not to her own relation. He would have spoken of it, wouldn’t he, if she had?”

“Poor man!” said Mrs. Stackhouse, with a hysterical laugh that she was unable to check; “he would have raised the whole neighborhood.”

“Probably,” said Stackhouse, the grave line of his mouth relaxing, “but he shut up his house and went away; the loneliness was too much for him. And I hear that on his travels he seems to have come across a sensible woman who took him and married him. Some middle-aged person like himself, who had no ties and was feeling lonely. It’s the best that could happen.”

“The blinds were up as I passed the house yesterday,” said Mrs. Stackhouse.

“Heavens, Robinson, what’s to be done?” burst out Stackhouse. “Look at us, talking coolly in the face of this horror! I can’t stand the thing much longer. Think of it, man! Week after week, there she sits, with her eyes fixed on me—”

“Oh, George, George!” said his wife, shuddering.

Robinson was sorry for them both. Evidently both of them were neurotic, and the tragic circumstance they related had affected them; their highly strung temperaments, acting on each other, had worked them up to a really dangerous pitch. And Stackhouse didn’t have enough to do. Perhaps it was worse for him to rust in this quiet parish than to wear himself out with work. The doctors had sent him on a sea voyage, had they? Months of idleness and too much introspection. Fools!

“Look here,” he said, “you go up and take over my job for a bit, and I’ll stop down here and discover something. You’ll be giddy at first, but the organization’s good, and I’ve got a regular martinet of a curate. He’ll manage you and see you don’t kill yourself. And I think Mrs. Stackhouse will find my house quite comfortable for a bachelor’s. I want a holiday badly—and you’ll soon shake off this obsession of yours in a London slum.”

Mrs. Stackhouse looked up eagerly at her husband. Relief at the great suggestion shone in her eyes.

“It would be cowardly to do that,” said Stackhouse, irresolutely. “I should feel as if I had deserted a poor soul that needs my help.”

“You’re not fit to help anyone in the present state of your nerves,” said his fellow-parson, and clinched the argument like a Jesuit. “How do you know she wants your help more than mine? Didn’t I see her too?”

CHAPTER II

The October sun shone aslant the quiet street as the Revd Mr. Robinson marched along it to call on his—or, rather, on Stackhouse’s truant churchwarden, Mr. Parker. He had a straw hat on and swung his stick.

Personally, he was hugely enjoying his interval of peace, and he had in his pocket a letter from his head curate extolling Stackhouse, who was working like a demon, and looked less ill. It only remained for Robinson to clear up the ghost worry in unmistakable fashion, which ought not to be too hard. He smiled. Odd tricks one’s imagination played sometimes! Recollecting Stackhouse’s unbalanced asseveration, he had himself experienced a slight thrill as he peered down the glimmering aisle on the following Sunday evening, and saw the same face that had impressed him before, the same dark eyes riveted on him. His robust intellect, that admitted all things to be possible, but few of them expedient, had been a little staggered by the sad intensity—imagination again—of her look. But a very commonplace incident had rescued him from any foolishness; just a little nodding child that had snuggled up against her as she gathered it in her arm.

He told himself that what he had to do was simply to make a few discreet enquiries and get acquainted with the disturbing young woman. He had spoken to the clerk after service, but that ancient worthy had not noticed who was sitting by the pillar; his sight, he explained, was not so good as it might be, with that chancy gas. Happen it was some stranger; folk was a bit shy of sitting that side because of the children fidgeting, and them boys—you couldn’t keep them boys quiet! Happen it was a teacher?

Clearly there was no disquieting rumor current, no local gossip; there seemed to be no foundation for any supernatural hypothesis but the overwrought condition of the parson’s nerves.

Robinson reached his destination, and pushed open the iron gate. Mr. Parker was out, but Mrs. Parker was at home, and the caller was marched into the drawing-room.

This was a mixture of ancient middle-class superstition and modern ease. It amused Robinson to compare the two, and even to track the ancestral album to its lurking-place behind a potted palm. While he waited he undid the stiff clasp and turned over the pages. Pity that people had given up that instructive custom of pillorying different generations for the good of posterity! It was an interesting study to look back and mark how family traits persisted, how they cropped up on occasion as ineradicable as weeds. He went through the book with the keen eye of an anthropologist. There was something elusive, something distantly familiar running through the whole collection. He must have met a member of that family at one time without knowing it. On the very last page he saw her; a photograph of a girl.

Breaking in on his moment of stupefaction Mrs. Parker sailed into the room, having furbished herself for the occasion with fresh and violent scent on her handkerchief. A dashing female, with quantities of blazing yellow hair and round eyes that stared and challenged; a splendid presence, indeed, in this sober house. But not at all the expected type of a middle-aged comforter. Much more like a firework.

She excused her husband in a high London voice. He was obliged to be at his office. Everything was in a muddle owing to things being left so long to the clerks. It really was time they came back, though how she was to endure this place—! Still, of course, with a motor—! Dull, did he say? It was simply dreadful. She had always warned Jimmy that it would be too much for her, but he had persuaded her at last.

“How lucky for him!” said Robinson, politely. The lady agreed at once.

“Rather!” she said. “Poor Jimmy! He must have proposed to me twenty times in the last two years!”

The accelerated clatter of a tea-tray approached. The bride was not going to allow her one visitor to escape her. She began moving things on the table.

“I have just been looking through that album,” said Robinson, turning it over as carelessly as he could. “That is a striking photograph on the last page. I fancy I have seen the original.”

She uttered a little shriek and closed the book.

“Oh!” she said. “Don’t you know? It’s Mr. Parker’s niece who committed suicide. A shocking thing, wasn’t it? Haven’t you heard about it? It was in all the papers!”

Eagerly she plunged into the story. His shocked countenance encouraged her to enlarge. He sat facing her across the gaudy little painted tea-cups (“a wedding present from one of my pals,” she remarked) that surrounded the heavy silver pot.

She poured out the whole history as Robinson had heard it from his fellow-parson, but with amplifications. He heard what a temper poor Kitty had, and what a drag on a girl it was to be tied by a long engagement. When a man she hadn’t seen for years wrote suddenly wanting her to come out at once and be married, no wonder the poor girl was terrified. Men alter so. He might have taken to drinking, he might even have grown a beard! And she didn’t dare to back out of it, because she was a religious girl, and she’d promised; and very likely he needed her bit of money. She wasn’t dependent on her uncle—oh, dear, no! Why, that heavy old tea-pot that made your arm ache belonged to her share! And she’d never stirred an inch from home. If Jimmy had had a grain of sense he would have put his foot down and said if the man really wanted her he must come and fetch her. But he didn’t think of it, and so—and so—Well, it must have sent her crazy. Look at her artfulness, making up that story about the dog, when she went out to buy the poison! Wasn’t it awful how cunning a person could be, and yet not right in the head, of course!

Her ear-rings tinkled as she shook her head with an air of wisdom. Her eager relation was no more personal than that of anybody retailing the latest sensational case in the papers—except in so far as she possessed the distinction of inside knowledge. There was a certain pride in her glib recital. But she was utterly unaffected by any breath of superstition, any hint of the supernatural hovering.

“Did you know her well?” said Robinson, trying to shake off his strange feeling of mental numbness.

“Oh, my goodness, no!” she said. “I never saw her. I didn’t get engaged to Jimmy till it was all over, and he came up to town more dead than alive, poor fellow, and told me how his circumstances had changed; and I was so sorry for him I just got married to him at once and off we went to Monte Carlo.”

An incongruous picture presented itself to her listener’s mind, the spectacle of this splendid person leading a dazed mourner by the scruff of his neck towards consolation. But the flicker of humor passed.

“I should like to meet your husband,” he said. She took, or mistook, him to be severe.

“I’m afraid we have both been naughty,” she said. “I know we have never been to church, and Mr. Parker a churchwarden, too! I used always to call him ‘the churchwarden’ when I wanted to tease him—and he used to get red and say it was a very important office. I must really apologize. And the cook says nobody will call on me till we’ve appeared at church. I’ll promise to bring him next Sunday evening. The cook says it used to be his turn to take round the plate at night.”

Eagerly, but with condescension, she gave this undertaking to satisfy the conventions (the cook having omitted to point out the superior social stamp of Morning Service), and effusively she shook hands. Robinson got out of the house and into the empty street. His mind began to work slowly, in jerks, like a jarred machine.

It was the original of that dead girl’s photograph be bad seen.

Something remarkably like panic shook him. He drew his hand across his forehead and found that it was wet.

By an odd trick of memory his own involuntary gesture reminded him of Stackhouse, who had wiped the sweat from his brow like that when the charwoman complained that her little girl had been telling lies. The insignificant incident, printed unconsciously on his brain, came back to him now with an unearthly meaning. He remembered that baby face, wide-eyed, insistent, too young to explain, too little to understand. And he remembered a sleepy head supported safely within a protecting arm.

“Good Lord!” he said, and his ruddy face was pale.

CHAPTER III

It was a hot, full church, the atmosphere thick with the breath of humanity and the purring gas. Evening service was popular with the multitude, and a wet night had driven all and sundry who would have been taking walks in the lanes to the only alternative. They pushed in, furling their dripping umbrellas and stacking them in the porch, till there was scarcely an inch of room in the middle aisle. And as the organ ceased rumbling and the packed congregation prepared to shout out the opening hymn a small, rabbit-faced man came stealing up the nave.

In his wake, plumed and hatted and scented, advanced Mrs. Parker, making her triumphal entry. Indisputably there was nobody in the church dressed like her. The man ushered her into her place, and took up his own, with a countenance of uneasy rapture, beside this tremendous fine bird he had somehow caged.

Robinson, at the reading-desk, shot one furtive glance at the side aisle and withdrew his eyes. He was conscious of a mixed sensation of relief and of disappointment. His timorous look had travelled along rows of blank, unimportant faces, and seen nothing to send a shock to his sober sense. The appearance, whatever under God’s mysterious providence it might be, was not there. He took heart to rate himself inwardly for a pusillanimous yielding to superstition. Obstinately he refused to let his attention wander and pinned his eyes to his book.

The service wore on, chant and psalm, prayer and preaching. He found himself halting unaccountably in the pulpit; the terse, vigorous words he sought for became jumbled in his head. In his struggle to keep the thread of his discourse and be lucid he had to fight a growing horror of expectation, a kind of strange foreknowledge that pressed on him. His eyes searched the dim spaces while his tongue stumbled over platitudes. He tried vainly to pierce the veil of mystery that hung over the darkened church. It was not time yet.

And then the glimmering lights went up.

She was there, in her place by the pillar, with her tragic eyes raised to him and the jewel glittering on her breast. All the other faces around her seemed indistinct, as if she alone were real—and yet the seat had been packed with worshippers standing up finding the places for the concluding hymn. Straight and still she stood among them, and, filled with a sense of impending climax, Robinson found it impossible to turn from gazing and go down the pulpit stairs. He, too, waited, watching, holding his breath, while the organ struck up and the churchwardens began to take the collection under cover of a lusty, long-winded hymn.

All at once, without consciously looking in that direction, he became aware that Mr. Parker’s place was vacant. He saw the small, rabbit-faced man drawing himself up to be stiff and pompous, carrying out his duty. Row after row he collected gravely, passing down the nave and coming up the side aisle. With a shock that staggered him for a moment the watcher realized that it was Mr. Parker’s part to collect on that side of the church. Would nothing happen, or would he, too, be granted the power to see?

The people were swinging through the third verse to an undercurrent of tinkling pennies. Nearer and nearer the man approached. Mechanically the watcher in the pulpit counted. Three more rows—two more—he had nearly reached her, but had made no sign. One more row and then—crash! The plate of coins went spinning in all directions. The man lay still where he had dropped on his face.

He did not die immediately. The numbing paralysis took a little time to kill. But he lay like a trodden insect, muttering, muttering. Blank terror was fixed immutably on his face.

It was clear from his own words that he had murdered his niece, but even the doctors did not know how much was intelligent confession and how much the involuntary betrayal of a stricken brain automatically reeling off old thoughts and guarded secrets.

“She’ll not have me, she’ll not have me; she says I’m not rich enough—”

That was his continual refrain, the fixed idea that had obsessed him, and that found utterance now at intervals, breaking even through the more coherent statements that had been taken down.

“It was all Bill’s fault. Why didn’t he leave his money to me instead of the girl? If I had it now; if I had it—! That fool of a girl, she thinks of nothing but her lover—”

Only for a moment the muttering voice would pause. Robinson, watching beside him, would speak of the everlasting mercy.

“She’ll not have me, she’ll not have me; she says I’m not rich enough!” and then, in the monotonous babble that was like a recitation, “I did it. Draw up the legal documents. Put it down. They called it suicide, that’s why she can’t forgive me. That’s why she came. Look at her, reproaching me with her eyes! Oh, my God, Kitty, take your eyes off me—”

On it went, over and over.

“I sent her to get the poison. I told her the dog had been run over in the street. I said I had shut it in the coach-house and the only merciful thing was to put it out of its pain. I told her to hurry and not to say anything to the servants—they would come bothering round, and they would not understand it was kindness—And I took it from her and put it into her lemonade on the sideboard. It was so easy. Look at her, look at her, come back to curse me!”

It was not hard to reconstruct the whole sordid story of a weak-minded man’s infatuation and greed. It was also wiser, remembering Stackhouse and his horror of letting his church be profaned by a sightseeing crowd, to acquiesce in the public view that it was remorse that had brought on the stroke that killed Kitty’s uncle. And so Robinson held his peace.

FOUR DREAMS OF GRAM PERKINS,by Ruth Sawyer

Originally published in The American Mercury, Oct. 1926.

Gram Perkins was not my grandmother. I had good reason to believe that she had died and received Christian burial a half century before I first set foot in Haddock harbour. Neither were the dreams of my dreaming; so my connection with her was always remote and impersonal. Nevertheless, I came to know through her all the horror and the fascination of a perturbed spirit.

For those who may not know the harbour, let me explain that it bites into the northern stretch of Maine coast. Summer resorters are still in the minority, and peace and beauty serve as perpetual handmaidens to those few exhausted, nerve-racked city folk who have found refuge there. I was there only a few days when the immortal essence of Gram Perkins confronted me. Perkins is a prevailing name at the harbour. A Perkins peddles fish on Tuesdays and Fridays. A Perkins keeps the village store in whose windows are displayed those amazing knickknacks somebody or other creates out of sweet grass, beads, birch bark, and sealing wax. A Perkins is framed daily in the general delivery window of the post office, and his brother drives the one village jitney.

It was Cal Perkins of tender years who indirectly introduced me to the mysterious dreamer of the dreams. Cal took me on my first scaling of the blueberry ledges. Standing like Balboa on the Peak of Darien he swept a hand inland and said: “Somewhars, over thar, lives Zeb Perkins. Hain’t never laid eyes on him myself, but Pa says you doan’t never want to hear him tell of them four dreams he’s had of Grandmother Perkins. Woan’t sleep ag’in fur a month ef you do.” It was not long before I discovered those dreams were as firm a tradition at the harbour as the “Three Hairs of Grandfather Knowital” are in Eastern Europe—only with a difference. Natives in the Balkans pass on their story for the asking; whereas in Haddock harbour they evade all questions leading to Gram Perkins, while their tongues travel to their cheeks.

One day Cal took me to the cemetery and showed me the Perkins monument. It was a splendid affair in two shades of marble with a wrought-iron fence and gateway, and all about it were the head stones marking the graves of the separate members of the family. I read the inscription on Gram Perkins’s stone:

Sara Amanda PerkinsBeloved wife of Benjamin Perkins, Sea Captain1791–1863May she rest in perfect peace!

“Wall, she didn’t!” Cal hurled the words at me as he catapulted through the gate, shaking all over like the aspen back of the lot. I caught a final mumbling: “Never aim to stop nigh her. Pa says I might git to dreamin’, too.”

Here was distinctly unpleasant food for thought. Already she had a firm grip on my waking hours, and there was no relish to the idea of her haunting my sleeping ones. The manner in which she possessed the town was astounding. She lurked wherever one went, popping out with the most casual remark when one was buying a pound of butter or a pint of clams. And yet, for all the daily allusions and innuendoes, one never got at the heart of the matter; one never rightly understood why Gram Perkins was and yet was not five feet below the sod. As for the dreamer of the dreams, one never found him clothed in anything more solid than words.

I questioned Peddling Perkins one Friday when he came to our house with the makings of a chowder. “Tell me,” I began, “where does Zeb Perkins live and what relation is he to you?”

He paused in his weighing. The scales hung from a rafter in his cart and worked somewhat mysteriously. He might have been weighing out the exact amount of relationship he cared to claim. “Fur as I can make out he’s sort of a third cousin.”

“Did he ever tell you about those dreams?”

“No, m’am!” He fixed me with a fore-warning eye. “What’s more, he hain’t never goin’ to. I seen Scip Perkins—time he told him. Scairt! Never seen a feller so shook up in his life. Didn’t take off his clothes and lay good abed fur a week. No, m’am!”

I questioned the post-office Perkins one day: “Do you happen to know what Zeb Perkins dreamed about his grandmother?”

“Dreamed! Gosh, what didn’t he dream? Think of anything a sensible woman, dead and buried fifty years, stands liable to do and you wouldn’t have the half of it.” He finished snapping his teeth together to signify that he had gone as far with those dreams as he intended to go—for the present, anyway.

A few days later I took the matter to the village store. I even bought a chain and earrings of sealing wax to make my going seem less mercenary. “Those dreams,” I ventured, “how did they happen and do they belong entirely to Zeb?”

“They do, God be praised!” Whereupon the storekeeper retired behind the necklace for a good two minutes, and then partially emerged to whisper, “No one’s layin’ any claim at all to those dreams but Zeb. And I’ve always thought myself if he hadn’t had them, no knowing what he mightn’t have had.”

II

For two recurring summers I stayed fixed at this point. And then came a spring when I slipped off early to the harbour for trout. The Perkins who drives the jitney met me at the wharf as I stepped from the Boston boat. “Hain’t a summer resorter nor a bluejay here yit,” was his greeting. “Weather’s right smart—nips ye considerable.” And it did. The water in the brooks was so cold my fingers remained stiff and blue all day. But the fishing was good, and in the end I caught something more than trout.

A morning came with a southeast wind. Up to that I had lost almost no flies, so I started out with little extra tackle. The middle of the morning found me a mile deep in an alder swamp, bog on one side and piled-up brush on the other. It was what you would call dirty fishing, and in half an hour I had lost every fly and leader I had with me. There was nothing to do but put up my rod and go back. In an effort to strike higher ground I came into what was new country to me. A trail led up toward where I judged the blueberry ledges would be, and climbing for a mile or so I suddenly broke through into a clearing and a wagon road. A grayish house stood beside the road. A thin spiral of smoke curled out of the chimney. On a split stake, even with the road, teetered a sign reading:

HAND MADE TROUT FLIESFOR SALE HERE

I attacked the door without mercy. A moment’s knocking brought the sound of stirring from within, and the door finally creaked open, displaying the oddest cut of a little man in a wheel chair. He blinked at me like some great nocturnal bird, and soon there was an intelligent wag of the head—more at my clothes than at me.

“Come in. Doan’t gin’rally git lady fishermen. Hearn tell they git ’em down to the harbour lookin’ jes’ as he-ish as the men.” He rolled his chair backward from the door, beckoning me to follow. I could hear him repeating the last of his words under his breath as if by way of confirmation: “Yes, sir, looking jes’ as he-ish as the men.”

He led me into a room that might have been identified even in the uttermost corner of the world as having been conceived and delivered in the State of Maine. An airtight stove centred it, and on its pinnacle stood a nickel-plated moose at bay. There were half a dozen pulled-in rugs: fruit pulled in; red, yellow, and purple roses pulled in; a rooster pulled in; and other things that defied the imagination. The two window sills were gay with geraniums and begonias. Crayon portraits panelled the walls, and between each portrait hung a hair wreath. Fronting the door was a shower of coffin plates, strung together with a fish line. A large coloured print of a clipper hung over the mantel, while all about hung trophies of the South Seas—strings of shells and beads and corals. But the most amazing exhibit was the feathers: peacock, egret, flamingo, pheasant, turkey, and cock tails, yellowhammer and bluejay wings, breasts, crests and what not. The work bench was littered with tiny feathers, partridge and guinea fowl, and spools of bright silk. He brushed all these aside and reached underneath to a drawer, bringing out a handful of trout flies. It took no close scrutiny to tell their exquisite workmanship.

“Pick out what ye want. Swamp back yonder jes’ eats ’em up, doan’t it?” And he smiled an ingratiating, toothless smile.

I made my selections slowly, studying the little man more than the flies. His head was as bald and pink as a baby’s. His lips were tremulous, and his eyes showed that pale blue opacity of the very old or very young. It was his hands that held me confounded. They were twisted like bird claws. How they could have ever taken wisps of feather and fine lengths of silk and wound them into the perfect semblance of tiny aërial creatures was more than I could conceive. He caught at my wondering and with a burst of crowing laughter he held the claws closer for inspection. “Handsome, hain’t they? Cal’ate I work ’em steady as most folks work a good pair. Can’t stand wet nor cold, no better ’n Gram Perkins could in hern. Good days she was the smartest knitter in the county.”

So here was another Perkins. I aimed my habitual question at him, expecting no better results. “Tell me, do you know anything about those four dreams?”

He sat a moment, motionless, in what one might have termed a vainglorious silence. He sucked his lips in and out over those vacant gums as if he found them full of flavour; then he suddenly burst into the triumphant crow of a chanticleer. “Yes m’am! Cal’ate I do know them dreams—seein’ I dreamed ’em. I be Zeb Perkins!” He said it with as sweet an unction as if he had announced himself King of the Hejaz. In a flash the room stood revealed anew. It spoke aloud of Sara Amanda Perkins, beloved wife of Benjamin Perkins, sea captain; of his clipper, of the relics of his voyages, of her handiwork in rugs and wreaths. The very begonias might be slip grandchildren of the ones she had planted. Here, indeed, was a stage set for those dreams. Here sat Zeb Perkins, playwright and stage manager, picking excitedly at his pink head, eternally ready to ring up his curtain. He caught my eye on the wreaths.

“Them little tow-headed fergit-me-nots belonged to her first son as died a baby. She set a terrible store by him. The black in them susans come from her sister Ida, my great-aunt Perkins. See them coffin plates. Ye’ll see every one of them was copper, nickeled over, every one but Gram’s. Hers was solid.”

There was a wealth of information conveyed in that last word. I had been standing until now. One of Zeb’s claws waved itself away from the coffin plates to a chair: “Set, woan’t ye? Ye’ll see them rockers under ye are worn as flat as sledge runners. That was Gram’s chair; and we wore them rockers off luggin’ her ’round. She was all crippled up, Gram was, same as me; only in them days there warn’t no wheel chairs.”

The chair was all Zeb claimed. There was no more rock to it than to a dray sledge. From the chair his eyes flew to the crayon portraits. “Look at them! Look at Marm—then look at Gram. Why, there was nary a thing Gram couldn’t do, for all her crippled-upness. Bake a pie, fry a batch o’ doughnuts, clean up the butt’ry. But Marm seems like she was born fretty and tired. Made ye tired jest to watch her travel from the sink to the cook stove. She’d handle a batch o’ biscuits like she never expected to live to see ’em baked. Jes’ lookin’ at ’em, can’ ye make out a difference?”

I did and I could. In spite of everything the artist had done to obliterate all human expression he had mastered the single point of difference. One face sagged utterly, the other looked out with sharp alert eyes on a world that interested her immensely. There was a grim humour about the mouth, and a firmness that spoke a challenge even at the end of a century.

“I tell ye,” Zeb’s eulogy was gathering momentum. “We boys set a terrible store by Gram. She was cuter and smarter tied to that chair than Marm was on two good legs—hands to match ’em. Golly! How sick boys git bein’ whined at. Didn’t make no odds what we done—good or bad—Marm al’ays whined, but Gram—she stood by like she’d been a boy herself. She’d beg us off hoein’ fer circus and fair days and slip us dimes for this or that. Cal’ate she’s slipped us enough nickels and dimes to stretch clean to the upper pasture. Pasture! Golly! When we was up thar, hot days, hayin’, she’d al’ays mix us a pitcher o’ somethin’ cool—cream o’ tartar water or lemon and m’lasses. When she had it ready she’d take a stick and tick-tack on the wind’y. She could whistle, too; whistle through them crooked fingers o’ hern like a yaller-hammer. She’d whistle whenever she wanted to be fetched anywhars; then one of us boys would come runnin’ and heave her to wheresomever she aimed to go—kitchen to butt’ry—butt’ry to settin’ room—settin’ room to shed.”

Zeb stopped here and illustrated. He put two of his crooked fingers to his mouth and shrilled out a thin, wailing note as eery as a banshee’s.

“That’s the way she done it,” he continued. “And Marm would fuss and fret and say she didn’t see why the Lord ’lowed a little crippled-up body like Gram’s to stay so chuck full o’ spunk. Some days she git sort o’ vengeful, Marm would, and tell Gram she’d better quiet down decent, or more’n likely she’d never rest quiet in her grave after she died.”

III

A hush fell on the room. There was a baleful light shimmering through Zeb’s dull eyes, his claws began a nervous intertwining. “Wall…” he broke the silence at last, “Gram died. Night afore she died seems like she got scairt. She grabbed us boys one after another and made us all promise we wouldn’t bury her till we were good and sure she was dead. ‘Keep me five days—promise me that,’ she kept a-sayin’. And we promised. Recollect it didn’t seem to me then as how Gram could die—so full of smartness and spunk. Even after old Doc Coombs come and pronounced her, seemed like she’d open her eyes any minute and ask us boys to lug her somewhars. ’Stead o’ that, she lay so quiet, seemed like I could hear Doomsday strike.”

The air about us became suddenly supercharged with something. Was it that ravenous desire for life that must have consumed Gram Perkins? Under their glass domes the hair wreaths seemed to move as if fanned by a breath. The feathers about us swayed. The rooster in the pulled-in rug seemed to pulse with life and a desire to crow. A crowing shook the room, but it came from Zeb.

“Hot! Golly, Gram died in the sizzlingest spell, middle of August, folks can remember. Didn’t embalm in them days, so ’twas ice or nothing. We drew lots for shifts—us boys. Ben and Ellery drew day; Sam and me night. Mebbe we didn’t work! Lugged in hunks from the ice house to the shed; thar we cracked and lugged in dish pans to the settin’ room. Crack—lug—mop—lug—crack. Five days! It’s been a powerful sight o’ comfort sence to know we kept Gram’s promise. Then come the funeral—smart one. Slathers o’ flowers and mourners and hacks. Cal’ate you’ve seen the lot whar we buried her?”

At the mention of burial a sense of enormity made me shudder. I was beginning to realize that the further Zeb progressed in the matter of the obsequies of Gram Perkins the more alive she became. At that moment she possessed the house—every crack and cranny in it. She possessed Zeb, and she possessed me. I found myself straining my ears for the rattle of dishes in the butt’ry or the sharp thin note of a whistle. Zeb’s ear was cocked as well as mine.

“Them dreams,” he said, pulling himself together. “First one come fifteen years after Gram died. All was gone from the harbour by that time but me. Ben took the pneumony and died quick. Ellery got liver complaint, turned yaller as arnicy and thinned out to a straw. Sort o’ blew away he did. Sam—he got trampled on by a horse. That left jes’ me. Night after I buried Marm I come back here and had my first dream. I was young ag’in. Boys back, Marm back, all of us settin’ thar at Gram’s funeral. Parson was a-prayin’—had been fur a considerable time. I could hear Nate French fumblin’ fur his tunin’ fork, so’s to lead the departin’ hymn when plain as daylight I heard a whistle. Yes, m’am. Then I heard a tick-tack—like Gram was knockin’ on some wind’y. Kept hopin’ she’d quiet down when out shot another whistle—clear above the parson’s prayin’. Nobody but me seemed to notice, so I got up gingerly and tiptoed over to the coffin and raised the lid.

“Thar she was—fixin’ fur to tick-tack ag’in. I grapped her fingers quick and shoved ’em back whar they belonged. Then I leaned over and whispered, loud as I durst, ‘Lay still, Gram. Parson’s nigh through and we’ll be movin’ along shortly. Folks ’ll be passin’ ’round in a moment to view the remains. Fur the Lord’s sake, close your eyes and act sensible.’ Wall…that fixed her. She give me a wink so’d I know she’d act right, and I tiptoed back to my place. They was all still a-prayin’—kept right on a-prayin’ twell I woke up. Three years later, come November, I had the second.”

Zeb shivered, and so did I. I wanted that second dream and yet I did not want it. Had I chosen I could no more have stayed it than one could have held back the second act of a Greek tragedy.

“We was on our way to the cemetery.” Zeb’s voice lifted me free of all choice in the matter. “I was ridin’ outside the first hack, bein’ the youngest, and I was thinkin’ what a fine day it was fur that time o’ year. Sort o’ funny, too, fur Gram died in August and here it was November and we was jes’ gittin’ to bury her. I was lookin’ at the hearse when it happened. Hearses was different in them days, black urns at the four top corners with black plumes stickin’ out and a pair o’ solid wooden doors behind. Above the poundin’ of the horses’ hoofs I heard a hammerin’ on them solid doors. Bang…bang… Plain as daylight. Old Jared Sims was drivin’, and I didn’t want he should hear so I sung out, ‘Cal’ate they’re shinglin’ the Coomb’s barn.’ He turned ’round in his seat to look, and jes’ that minute thar come a regular whale of a hammerin’, and the doors of the hearse bust open. Thar was Gram—top of her own coffin, peekin’ down low at me and beckonin’ fur me to come and git her.

“Mad! I was as mad as a hornet. I went back to that wink she’d given me in t’other dream and seemed like she’d gone back on her word—something Gram had never done livin’. I was off the seat of that hack in a jiffy, runnin’ aside the hearse. When the goin’ slowed up I stuck my head inside and hollered, ‘Ye git straight back whar ye b’long! And what’s more ye stay thar!’ Then I begun to whimper like I couldn’t stand my feelin’s another minute. ‘Gram,’ says I, ‘hain’t ye got any heart? Do ye want to disgrace us boys? How’ll ye cal’ate we’ll feel to have the neighbours thinkin’ we’re tryin’ to bury ye ag’in your will? We give ye them five days like we promised—can’t ye lay down decent and proper now?’

“That settled her. She turned, meek as a cow, climbed back into her coffin and closed the lid down. I went back to the hack and climbed up. We was still a-goin’ when I woke up.”

IV

An interlude followed. I tried to bring back my mind to the reality of life as I knew it to be. I fingered my trout flies and did my best to image the still, deep pool below the swamp where I had been on the point of casting just as my last leader broke. Half an hour more I could be back there, casting again. But the pool and the trout faded into oblivion beside the sterner reality of Gram Perkins. I was on the hack with young Zeb, my eyes fastened in growing perturbation on a pair of solid black doors.

“Jes’ started on our January thaw when the next dream took me,” broke in Zeb. “We’d reached the cemetery. Grave dug, coffin lowered, folks standin’ ’round fur a final prayer. To all appearances everything was goin’ first rate. But the sexton hadn’t more than picked up his shovel, easy-like, when out comes a whistle, clear as a fog horn. I opened my eyes quick and looked down. Thar was Gram, poppin’ out like a jack-in-the-box, lid swung wide open and both hands reachin’ fur the dirt the sexton was shovellin’ in. Yes, m’am! Ye never saw dirt fly in all your born days the way Gram made it fly. At the rate she was goin’, I knew we’d be standin’ thar twell Doomsday, gittin’ her buried.

“Everybody else was prayin’ hard along with the parson, and he was ’most to the Resurrection. I knew somethin’ had to be done quick, so in I jumped. I slapped the dirt out of her hands hard like you would with a child and says I, ‘Land o’ goodness, Gram, what ails ye? We’ve fetched ye along to what the Bible calls your last restin’ place. All we boys is askin’ of ye now is to keep quiet and rest twell Jedgment Day.’

“The words warn’t more’n out afore I knew I’d said the wrong thing. She didn’t lay any more store ’bout this eternal restin’ than what ye would, settin’ thar fingerin’ them flies. She give me the most pitiful look ye ever saw on a human face. It said, plain as daylight, ‘Zeb, lug me back home and let me git to work ag’in.’

“Wall…I took to whimperin’ like a two-year-old. ‘Ef ye woan’t do it fur the Bible,’ says I, ‘do it fur us boys. Ye’ve al’ays been terrible proud of us—al’ays wanted we should have jes’ what we wanted, and thar’s nothin’ in the whole o’ creation we want so much this minute as to see ye restin’ peaceful. Git back in. Close your eyes, fold your hands, git that listen fur the last trumpet look on your face. Hurry, woan’t ye? The sexton’s shovellin’ like sixty.’

“She give me another of them pitiful looks—nigh broke me all up—and she sort o’ slid back and slammed the lid down on her fur all the world like one of these cuckoo clocks. I lit out and landed side o’ the parson jes’ as he said ‘Amen.’… ‘Amen,’ says I, thankful-like. ‘Amen,’ says the sexton…. ‘Amen,’ says the mourners in a roarin’ chorus like the sea. And then I swear to ye that way under the dirt I heard Gram sing out Amen! Tell ye I woke in a sweat!”

“Cold sweat?” I asked. It was all I could think of.

“Cold as a clam, dripped with it.”

“That makes three.”