Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

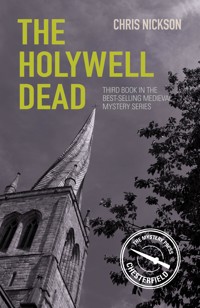

- Herausgeber: The Mystery Press

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

John the Carpenter has been happy to leave the investigation of death behind. For six years now he's been content to work with wood. His life looks prosperous, but times are growing desperate. Then the coroner summons him to look at the mysterious death of an anchoress, a religious woman who lived in confined solitude. She's been murdered. Her father is an important local landowner, a man of influence with the crown. He's distraught, and the money he offers John to find the killer can solve his problems and leave his family comfortable for life. But the path to the truth leads John to the heart of the rich, and back into history, to places where he's not welcome and in danger for his own life. Can he find the killer? And what will happen if he doesn't?

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 374

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

To the church with its glorious crooked spire,the original inspiration.

With gratitude to Waterstones in Chesterfieldfor their support with this series.

For Chesterfield Museum, where the windlass sits:it’s helped my thoughts turn.

First published 2020

The Mystery Press is an imprint of The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Chris Nickson, 2020

The right of Chris Nickson to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7509 9547 4

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ International Ltd.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CHAPTER ONE

Chesterfield, September 1370

John felt the axe bite into the wood, deep enough for it to stay. He straightened up and stretched, then wiped the sweat from his face with an old piece of linen. Chopping the branches from a fallen tree was labour to make the muscles ache and moan in protest.

It had come down during the night, blocking the road that led north from Chesterfield to Sheffield. At first light the town bailiffs were out knocking on the doors, begging all the craftsmen and labourers in town for their help. Everyone with tools and a strong back. John the Carpenter had been one of the first, bringing his mute assistant, Alan. Soon a dozen men and more were working on the tree with axes and saws. It was an old, thick elm that had rotted at its core until the weight became too much and it had toppled.

Now the trunk lay in sections the height of a man, each one pushed to the side of the road. The only task remaining was to strip the branches, and they were almost done with that. John told Alan to fetch them ale from the jug a kindly goodwife had left. Only six men were still working. Themselves, three foresters who seemed locked into their labour, never joking or gossiping, and a farmhand, a sullen man sent along by his master who kept pausing to grumble.

The sun sat high in the sky. But it was September now, with none of the fierce heat that had burned his skin all summer and turned it the colour of tanned leather. A pleasant day, with the high clouds flitting and dancing above the fields.

At least he’d be paid for this, John thought. Fourpence, a full day’s wage. And there were one or two pieces of wood he might be able to scavenge and shape into things later, once business had ceased for the winter.

Truth be told, he was grateful for any money at all. It had been a meagre year. The only good thing was that the prayers of all in the town had been answered; no cases of plague in the heat of summer gave them all the hope that it might never return. He crossed himself at the thought.

For him, though, things had been hard. Two more joiners had moved to town and brought competition. Their work was rough and ready, they weren’t proper craftsmen; still, they were able to handle most jobs that had been his. Men who charged less than he did and took much of his business. Incomers. Silently, he laughed at himself.

John had been here for ten years now. He was married, he had three children. Much of the time he felt part of the fabric of Chesterfield. Still, to some who’d been born and raised here, he was as much an outsider as someone who’d arrived just the week before. Another decade and he still wouldn’t be a native to people like that.

He carefully pulled out his axe, wiped it with an oily rag and inspected the edge, running it along his thumb, before putting it back in the leather satchel. The tools he owned had once belonged to his father. They’d served the man well until he died in the Great Pestilence. God’s blood, that was more than twenty years ago now. A lifetime and more.

The hammer, the saw, the awl and everything else had kept John alive as he wandered from place to place, growing from a boy to a young man and learning to harness his natural feel for wood. Life on the roads had taken him to York; for several years he’d honed his craft there, constantly employed in the frenzy of church building until circumstances forced him to leave. Only after that had he ended up in Chesterfield.

This was home now. He was settled, he’d lived here longer than anywhere else. To anyone looking at his life, he was a success. He’d become a family man with all the responsibilities that brought. He had his business as a carpenter, he owned two houses, he employed a young man. But he knew how readily appearances could deceive.

One of the properties, on Saltergate, had been in his wife Katherine’s family; she was the oldest child, she’d inherited it when her mother died. The other, around the corner on Knifesmithgate, had belonged to Martha, the old woman who was friend to them both. She’d willed him her house when she died two years before. By then John and his family were already living there, caring for the woman in her old age. Martha had stood godmother to two of their children and they’d named their younger daughter after her; her memory would live on in his family.

Both houses desperately needed work. They’d been ignored for too long. John had done what he could, but so much was beyond him. The roof at Martha’s old house leaked into the solar. It was going to need new slates before winter set in. If he left it for yet another year, the beams would begin to rot and it would be a much bigger, harder job. But a tiler would cost money he didn’t have in his coffer.

He rented out the Saltergate house. The amount it brought barely covered all the never-ending list of repairs.

The constant worry about money grew more pressing every month. It kept him awake long into the night and gnawed at his heart. No peace. The other day he’d seen his reflection in a pond, shocked at the way his hair was turning grey and the lines that furrowed his face.

This year it was coming to a head. He was going to have to make a choice. Unless something happened and a fortune tumbled into his lap, he’d have no choice but to sell one of the houses. And he had no faith in miracles. Not for a man like him.

He loved Katherine’s brother and sisters, but he was glad they were no longer part of the household. Fewer mouths to feed was a blessing when he had three children of his own. His brother-in-law Walter and his young bride were settled with her parents in Bolsover, while Katherine’s two sisters were in service on a farm near Holymoorside.

He sighed and began the walk back towards Chesterfield. It wasn’t far, no more than a few minutes away. The spire of the church soared high into the sky, visible for miles around, as clear and welcoming as any beacon.

He’d worked on that when he first arrived in the town. Only for a short time, though. After a few days John had found himself a suspect in a murder in the church tower, a stranger who needed to clear his name.

That had happened ten years ago. Where had the time gone? It happened when he first knew Katherine, before he’d become a husband and a father and all the things that had happened since. John felt the weight of his own history pressing down on his shoulders. What could he do except carry on? With God’s blessing, everything would be fine. He had to believe that. They’d all survive and prosper in His grace.

‘Who knows, maybe we’ll have work waiting for us in town,’ he told Alan, with the kind of hope he didn’t feel.

The lad was twelve now, as much a natural as a carpenter as John had been himself. He carried his own leather satchel of tools that banged against his back as he walked. He was growing into a tall young man with broad shoulders, his hands rough and thick with calluses from the work they did. Alan was old enough and certainly skilled enough to strike out on his own. But he was mute and he didn’t know how to write. His fingers were quick to make signs, but most people would never understand them. It was impossible for him to obtain work himself, and he needed to be with someone who wouldn’t take advantage of him. Six years before, the boy had started out as John’s apprentice and bit by bit the lad had learned everything he had to teach. Now he was… what could he call him, John wondered? An assistant? An equal? He clapped a hand down on the boy’s shoulder and watched the tiny flakes of wood rise from his battered tunic.

The road was dusty; they’d had no rain for over a fortnight. A few horses and carts passed them, and he could hear the sounds of the weekday market on the north side of the church as they climbed the hill. A town of stone and slate, of timber and limewash. Beautiful, in its own coarse way. Home.

Not too much more than a week and the annual fair would begin. It would be eight days of feasting, noise and entertainment, with all manner of goods for sale. Music and players, tumblers and jugglers. It would all begin with a service and blessing in church on the day of the exaltation of the Holy Cross. Already he could sense the excitement around town. Every year it was exactly the same. The children caught it first, dancing through the days in anticipation, then the fever started to affect the adults.

For a brief while, Chesterfield would feel like the most important, magical place in the kingdom. People came from all over for the fair. Not just the North, nor even England, but everywhere. John had met many from beyond the borders: Welshmen, Irishmen, even a Dane once, with his happy, sing-song accent; a German and a man from the lowlands of Holland. An entire world came to Chesterfield, bringing things beyond the locals’ imagination. Goods to buy, foods to taste. Minstrels and clowns to entertain. There would be merchants and goodwives shouting out their wares and displaying all the luxuries on offer. Everything from the ordinary to the exotic. His children were counting down the days. Foolishly, he’d promised Martha a length of ribbon from the fair. She’d remember, of course, but he had no idea how he’d be able to afford it for her. The worry of an empty scrip crowded his mind.

Before he went home he’d stop at the Guildhall and pick up his wage for today’s work. Four good pennies to spend on food. Katherine would be glad to see that. The garden behind their house had been fruitful this year, but the season was coming to an end and it didn’t offer them bread or milk or meat. Only the occasional hen that had grown too old to lay eggs.

He looked as Alan nudged him and pointed towards a man hurrying along with a forceful stride and a determined look in his eye. He was wearing a dark green woollen tunic bearing the coroner’s badge, he had a sword hanging from his belt, and he was coming directly towards them.

Pray God the man wasn’t seeking him. It couldn’t be good news if someone like that wanted him. Either something awful had happened, or the coroner wanted his help. Six years had passed since the last time that had happened. That was when de Harville was still alive and held the office of King’s Coroner. Katherine had always hated the idea of him working for the man. Three times it had happened, and he’d always undertaken the work reluctantly, but what choice did anyone have when a rich man in authority demanded his services? The last time he’d almost been killed. Enough, his wife insisted, and he’d been quick to agree.

Then de Harville died, and John was thankful that his successor, Sir Mark Strong, had chosen to go his own way. He had no desire to be tangled up in any of that again.

‘Are you John the Carpenter?’ the man asked as he came closer.

‘I am.’ He felt his heart sink.

‘The coroner would like you to attend him.’

‘Me?’ John asked. ‘Are you sure you have the right man? Why would he want me? I’ve never done any work for Coroner Strong.’

He knew the words were hopeless, but he had to say them, to try and ward all this off.

The man shrugged. He was well-muscled, with fair hair and a ruddy complexion, a pair of smiling blue eyes.

‘Nay, Master, I’m not the one to ask. I’m just the messenger. All I do is what I’m told, and my order was to come and fetch you. I don’t know what he wants. But I can tell you this: there’s a body at Calow and he’d like you to see it. You’re welcome to walk out with me if you choose.’

Calow? It was nothing more than a hamlet half a mile from the town. He could picture it in his mind: just three or four tumbledown little cottages and a tiny church with an anchoress’s cell. What could have happened out there to draw the coroner’s attention?

‘Is it a murder?’

The man shook his head. ‘Couldn’t tell you, Master. He gave me my order, that’s it.’

‘Who is it?’

‘I can’t say that, either. Coroner Strong will tell you himself, Master.’ His face flickered with impatience. ‘We should set off.’

‘Not yet,’ John told him. He wasn’t going without telling Katherine. She wouldn’t be happy; she wouldn’t want to see something like this bubbling to the surface once more. She’d married a carpenter, not a man who investigated deaths, even if he had a talent for finding the awkward truths behind someone’s passing.

As it was, she stared at him with growing anger as he told her. When he finished speaking she scooped up Martha and stalked through to the buttery without a word.

‘What else can I do?’ he asked as he followed her. ‘I don’t have a say in it. You know I can’t refuse a coroner.’

Katherine turned. ‘You’ll do what you want, the same as ever.’ Her voice was cold as winter ice. ‘I know the coroner doesn’t care that you have a living to make and a family to feed. But what about you, husband? Do you care?’

‘You know the answer to that,’ he told her. ‘You know it just as well as I do. It’s the only thing I can think about.’

She dropped her eyes and ran her fingers through their daughter’s curls.

‘They make me so angry, the way they feel they can treat us all like this, like we’re nothing.’

‘Look, let me go out and see,’ he said. ‘It might be nothing at all. We’re standing here thinking it’s murder and it could prove to be something different.’

‘Of course.’ She snorted. ‘And if wishes were horses, all the beggars would be riding up and down the King’s highway. We’d have a stable full of them in the garden.’

She was right. Imagining anything else was pointless. The coroner’s man wouldn’t be waiting impatiently in the September sun unless Strong suspected murder. He kissed Katherine, then Martha, and left. In the hall of the house, he picked up a jug of ale off the table and filled one of the clay cups, drinking it down in a single swallow. Out on Knifesmithgate John brushed tiny flecks of sawdust from his tunic and hose. He didn’t look like a man of property at all. He looked to be exactly what he was – a carpenter trying to scrape a living. But at least he’d appear presentable to authority.

‘I’m ready.’

‘We should hurry,’ the man told him. ‘The coroner doesn’t like to be kept waiting.’

John was determined to hold on to the tatters of his pride. He might be summoned, but he was his own man. Strong didn’t possess him.

‘Whose is the body?’ he asked.

The man shook his head. ‘I told you, it’s not my place to say anything, Master. Coroner Strong said to bring you and nothing more. He wants you to make up your own mind, that’s his plan.’

A suspicion of murder, then, but apparently no certainty. The coroner wanted another opinion. But why him? He’d find out when they arrived.

Side by side, they crossed the bridge over the Hipper, then turned along the path to Calow. It wasn’t a road, just something slightly better than a track, wide enough for a single cart, the earth beaten down by feet and horses’ hooves. Clouds passed overhead, then the sun appeared again; the September air remained pleasant. Out in the fields, men were guiding their teams of oxen, ploughing the stoops left from the wheat back into the ground. The harvest was done and it had been a good year. None would starve to death this winter. There would be grain for bread and food for the pot.

He followed the man as he bore off on a path that cut to the right. Well, well, John thought. It wasn’t in Calow itself. They were walking towards the church. It stood on its own, perhaps a quarter of a mile beyond the hamlet. Far enough to seem distant, yet still within shouting distance. It was placed to serve all the tiny settlements close by – Duckmanton, Ingersall Green and the others.

Who was the victim? It couldn’t be the priest. He only came for service on Sundays. That meant it had to be the anchoress herself.

Two men were gathered by the stone cell. John recognised Sir Mark Strong, the coroner, dressed in fine cloth so black it seemed to drown the light, and dark hose; he’d seen him often enough around Chesterfield, although they’d never had cause to speak. Next to him stood a man wearing a clerk’s robes. Not a tonsured monk, but a layman with ink on his fingers and the type of squint that came from spending too long looking at words on paper and in books. Strong glanced up as they approached. His hair was short, cropped close to his skull, a bright silver-grey that caught the light.

‘Are you the carpenter?’ His voice was deep, coming from somewhere low in his chest. John felt as if the man was inspecting and assessing him.

John bowed his head. ‘I am, Master.’

‘I’ve been told that you used to help de Harville when he was the coroner.’

‘That only happened very rarely, Master. And the last time was six years ago. As you must know.’ Maybe that would be enough to convince the man he wasn’t the one for this work.

Sir Mark frowned. He glanced at the clerk, who shrugged. ‘But you were able to solve puzzles that defeated other men. You found out how people had died and if someone had killed them.’

‘No, Master,’ he replied, and watched the coroner’s eyes widen in surprise. ‘I had luck, and God’s grace helped me.’

Strong waved the words away and gestured at the cell.

‘Do you know who lived here?’

‘Gertrude the anchoress.’ Everyone for miles around knew about her. The goodwives all swore she was a holy woman. They’d walked out from Chesterfield to see her after she arrived, to inspect her and form their opinions. They’d been surprised to find such serenity and humility in someone so young.

The anchoress sought a life of prayer and contemplation. She lived in solitude, walled away, a religious recluse. Food was provided through an opening and she talked to those who came to visit and offer gifts in return for prayers and advice. But she could never walk with them. She’d chosen to make the small cell her world. A slit between it and the church allowed her to observe services and receive the sacrament.

Gertrude had only been there for twelve months; it seemed like nothing at all. Barely more than a girl, she’d taken the place of the previous anchoress who died of old age. And now her time had passed, too. John crossed himself.

‘What killed her?’ he asked.

‘Go inside,’ Strong ordered. ‘Take a look. Tell me what you see. I’ve been in there and for the love of Our Lord, I can’t find a cause.’

Someone had prised away some of the stones, making a space just large enough for a man to crawl through.

John had never come out here to see the anchoress for himself. Why would he, when she craved solitude and prayer? But even so, it was impossible to avoid the gossip about her that passed around Chesterfield. Her father was Lord l’Honfleur. A rich man who moved in royal circles. He had influence. He owned this manor of Calow, John knew that, and many others besides, probably far more than a poor man could count.

‘Go on, tell me what you think,’ Strong urged.

With a quizzical look, John squeezed himself through the small opening and into the cell. He squatted on his haunches, letting his eyes adjust to the gloom. He inhaled and the stench hit him. He could feel the bile rising in his stomach and willed it down. A rank perfume of old vomit and shit filled the air as it stifled and clung. Decay, putrefaction. Death. He breathed through his mouth, then his ears picked out the constant buzzing of flies, a low, insistent drone. Slowly, very slowly, his vision began to clear. The main room was so small it was oppressive. Perhaps six paces long by four wide and barely tall enough for a man to stretch. He picked out the opening into the church along one wall. A small room stood in the corner. He opened the door. A jakes, with a bucket and seat for the anchoress to relieve herself. He turned back to the room. A window to the outside world in one wall, its shutter partly open. John stood and drew the wood all the way back to let the light flood in. Suddenly everything stood out in sharp relief. The pools on the floor were crawling with thousands of insects. He tried to brush them away, but it was an impossible task; they returned as soon as his hand had passed.

A pallet sat in the corner, a rough-cut wooden frame topped with straw and a threadbare blanket. No comfort of any kind for the anchoress. There wasn’t even any space for a fire or a brazier to keep herself warm. Winter would have been a brutal season in here. Even now this place carried a damp chill that seemed to ooze out of the stone. He took another shallow breath. The young woman was slumped against the wall, her eyes wide with agony and fear. Her hair was hidden by a wimple that had long since lost its whiteness. Her gown was expensive, made from finely woven wool, but it had been worn to a threadbare shine in patches. John knelt by her, tracing the pale flesh on her hands and face, then looking at her body. He half-turned the corpse. The coroner was right. There was no sign of a wound or an injury. No blood. He sniffed the corpse’s mouth, but he couldn’t pick up any scent of poison. There was no sign of it, he thought; no discolouration of her lips or fingernails.

Very strange. There was nothing at all to show the cause of her death. And certainly nothing to indicate it had been deliberate. No violence of any kind. But the pain that had contorted her face told its own story. Gertrude’s death had been terrible. John traced the sign of the cross over his chest and studied the room once more.

A knife sat on a low wooden table, but the blade was too blunt to do any damage; it would barely be able to cut meat. The anchoress had knocked the plate from her final meal on to the floor. It covered the few scraps of food the insects hadn’t already carried away. He brushed the remnants back on to the plate then crawled out into the light.

‘Well?’ the coroner asked. ‘What did you see?’ But John ignored his question. He was studying the food. The answer had to be in there. That had to have been what killed her. But what was it?

It took him a few moments. Then he understood. A faint memory grew sharper as it took on form in his mind. The pieces of mushroom had been cut very fine. Only the sickly yellow colour and the sheen on the cap gave it away.

‘That,’ John said. He pointed, careful not to touch.

Strong stared. At the plate first, then at him.

‘Why? What is it?’

‘People call it the death cap mushroom. That’s what killed her.’ Most people out here would have known about its danger and kept away from it, he thought. Unless they wanted to kill.

The coroner didn’t look convinced. ‘How can you be sure?’

‘I know,’ John replied, ‘because I saw someone eat one once.’

It came roaring back into his head. He was just nine, orphaned for a twelvemonth by the plague and simply trying to stay alive as he travelled through a land that the pestilence had laid waste. He’d been with a small group of starving men, tramping their way along the road from Ripon to Knaresborough. They’d been going slowly. Half of them were too weak to walk more than a mile without resting. Their tunics and hose were all filthy, the soles of their shoes battered and worn all the way through by time on the highway. One of them, Seth, had spotted the mushrooms, deep in the cool shade of a tree where he was resting. So desperate for anything at all in his belly, he’d started to eat them before anyone could stop him.

John didn’t understand. He couldn’t. He was too young to know. He didn’t see what the man had done that was so wrong. Seth was hungry, he’d seen food, he’d eaten it. John’s father had never told him that some mushrooms were deadly. The plague had taken him before he could teach that lesson. Him and so many others. In the end, it was the hard, toothless man leading their party who explained it all to him.

They struck up a rough camp and waited for the death. Someone trapped a coney and they roasted it over the fire. He could still remember the warm grease running down his chin as he gratefully chewed a scrap of meat and sucked at the bones.

Seth took a day and a half to find God’s peace. He was in pain the whole time, but there was nothing they could do to ease it, no plants that might take the agony away for a while. John could still hear the cries. Seth suffered, screaming into the air, his body beyond his control, even when there was nothing else left inside. The silence when his breathing stopped had brought a sweet relief, and then guilt. They buried him. A shallow grave was the best they could manage, piled high with stones to keep the animals away from the corpse.

‘Are you positive?’ Strong asked him now.

‘Yes.’ He had no doubt at all. It was one lesson he could never erase. ‘It would have taken her a long time to die.’

‘How long?’ a voice asked.

John turned. He hadn’t heard the man approach, coming around from the other side of the church. Lord l’Honfleur. Dame Gertrude’s father. He wore his wealth very easily and naturally. A light silk surcote dyed a deep, rich blue, cut to fall flatteringly around his body. He was well-barbered, his cheeks clean and still pink from the razor, and his grey hair was cut short. He had a fighting man’s padded jerkin that reached down to his thighs, and high, shiny boots of supple leather that sat snug against his calves, over blue hose.

‘God speed, my lord,’ John lowered his head. ‘A day at least.’

‘I see.’

The grief bowed the man down like a powerful weight he couldn’t support.

‘I’m sorry, my lord,’ John said. ‘May God’s light be on her now.’

The man nodded absently and took a deep breath. He started to pace around, clenching his fists then opening them again.

‘Why?’ he asked. A small word, a simple question, but none of them could answer it. ‘Why? Why would someone do that?’

John looked at the coroner, then said: ‘I don’t know, my lord.’

‘She was always her mother’s favourite.’ L’Honfleur started to speak as if he hadn’t heard him. He was tracing a path backwards through the years. ‘Gertrude was the youngest, she was the one most like her.’ He closed his eyes for a moment. When he opened them again, a tear began to roll down his cheek. He let it fall, not even aware it was there. ‘After my wife died, Gertrude found comfort in prayer and the church. In the priest and the sister who was teaching her.’ A brief, wistful smile of remembrance. He didn’t want an answer; maybe it was enough for him to know they were there, that someone would hear what he needed to say. ‘I was urged to make a good marriage for her. I was already discussing it with a family, but she begged me to let her become a nun. Begged me. Nine years old and the only thing she wanted was to leave this world behind her.’ He shook his head in wonder. ‘My wife had always been a friend to the convent. How could I refuse? The vocation was plain in her eyes. The need.’ He took a few more paces. ‘And then she craved more and more solitude. When the old anchoress died last year, she pleaded with the Mother Superior to let her take on this task.’ He breathed very slowly and seemed to return to the present. He stood, legs slightly apart, shoulders back. ‘Who are you, anyway?’

‘John, my lord. John the Carpenter.’

L’Honfleur raised an eyebrow in surprise. ‘What kind of carpenter knows about death?’

‘He did some work for the old coroner,’ Strong said. ‘You remember him – de Harville.’

The man nodded. His eyes peered into John’s face, examining it for truth and honesty. ‘Yes, I think I recall your name now. You’re the one who has the gift for finding murderers.’

‘Not really, Master. And all that was a long time ago.’ He stumbled over the words. The very last thing in the world that he wanted was to have l’Honfleur demanding his services.

‘But you were able to identify the mushroom.’

‘True enough, Master.’ He could hardly deny that.

L’Honfleur sighed. ‘Tell me this, Carpenter: do you believe my daughter’s death was an accident?’

What kind of answer could he offer? A lie that might ease the man’s heart? That wouldn’t give the girl in the anchorite cell any justice. Once the truth eased out, and it surely would in time, would l’Honfleur come after him? Honesty was painful, but it was better. It could burn and cleanse. Anyone who gathered mushrooms should know to avoid the death cap.

‘No, my lord,’ John said after a moment, ‘I don’t think it was.’ He hesitated, weighing his words as if they were gold. ‘It’s possible that someone made a mistake. But my belief is that this was done deliberately.’

Who would want to kill a young nun? How could she have done anyone any harm in such a short life, especially alone out here? He thought of the pain and fear crowded together on her face. What had she gone through, hour after hour, on her own? What reason could someone possess for doing that to her?

L’Honfleur began to pace once more, hands clasped behind his back. This time he walked all the way to the treeline before turning and coming back. Strong and his clerk remained silent, staring at the cell. John waited, silently cursing the coroner for demanding that he come out here.

‘Carpenter,’ l’Honfleur said when he returned, ‘I want you to find the person who killed my daughter.’

‘My lord—’John began. For the blessed love of God, not that.

The man rode roughshod over his protest. ‘You’ve done it before. You used to have a reputation for it. You can’t deny that.’ His voice softened and there was a plea in his eyes. ‘I’m asking you to do it again. For me.’

It might have sounded like a request, like begging, but it was an order. And one he dare not refuse, not when it came from a man with l’Honfleur’s power. A word would be all it took to ruin a life.

He bowed his head. ‘Yes, my lord.’

‘Succeed and I’ll pay you fifty pounds.’

John shook his head. He frowned in disbelief, in shock. He’d misheard. He must have. That or he’d slipped deep into a dream. Fifty pounds? Fifty pounds? It wasn’t possible. No one would offer that much, certainly not to someone of his status. It was more than he could dream of making in more than ten good years as a carpenter. Plenty of wealthy merchants with their servants and their beautiful clothes earned far less than fifty pounds in a year. It was enough to repair both his houses and leave ample to keep his family comfortable until he was old. He glanced at Strong and the clerk. Both of them were staring at l’Honfleur with their jaws wide.

‘Fifty pounds, my lord?’ John’s voice was a croak. He was afraid to ask, in case the man realised his mistake and took back the offer.

‘Fifty.’ He nodded towards the other men. ‘You have witnesses, Carpenter. I’m a man of my word. Fifty pounds if you find the killer by the time the fair starts. What do you say?’

‘Yes, my lord.’ He agreed. But there was never a choice, and l’Honfleur knew it as well as he did.

CHAPTER TWO

‘You made the right decision, Carpenter.’

L’Honfleur had remained at the anchorite cell, making arrangements to have his daughter brought to the church for her burial. John and the coroner’s clerk were trudging back to Chesterfield, while Strong rode alongside them, looking down on the world from the saddle of his horse.

‘Did I have a choice, Master?’

‘No, you didn’t, and it would have been unwise to try and refuse. What do you know about him?’

‘Very little.’ What did he know about any man with titles and lands? About as much as he knew about the countries beyond the Middle Sea. The rich were there; they existed in a world far removed from his own. They had money. It built a wall around them, left them warm and kept everything at bay. They were the ones who ran the country, who looked after the grand affairs. But none of that really touched his life, or anyone he knew. He lived among the small people, running around like ants and trying to avoid being crushed under the soles of those who controlled everything.

‘He’s a very powerful man. Twelve manors across Derbyshire and Yorkshire.’ The way Strong spoke, it was supposed to impress him. Instead it made the man seem like someone who could part with fifty pounds and never notice it had gone. ‘A man who has the ear of Alice Perrers, the King’s mistress.’

And what did that matter, unless it was some sort of threat? He hadn’t wanted to do this, but with little choice, he’d agreed to look into Gertrude’s death. The money was meant to tempt him and keep him going, and he knew that it would. Now he had to hope he succeeded and earned the reward. It was the only thing about the whole business that made sense to him.

‘I shall need some help.’

‘What do you want?’ Strong asked. They’d crossed the bridge and were climbing up Soutergate towards the church with its towering spire.

‘Men,’ John told him. He was certain the coroner would agree; he’d want to please l’Honfleur.

‘Let me know when you need them and how many. I’ll make sure they’re available.’

‘And I’ll need to be paid.’

‘But my lord said…’

‘That doesn’t feed my family while I’m looking into this,’ John insisted. ‘I can’t do my own work, so I need to earn.’

The coroner eyed him suspiciously. ‘I thought you owned two houses.’

‘I do.’ There was no need to give the man the full truth; the rumours would simply fly all over Chesterfield. ‘But when you hire a labourer, you pay him for his work.’

‘Very well,’ the man agreed with a grudging sigh. ‘Four pennies a day. But he wants this complete by the time the fair starts, Carpenter. I hope you’ll remember that.’

‘I will, Master. All too well.’

• • •

John counted out his four pennies from the Guildhall on the table in the hall.

‘I’m glad you remembered to collect your pay,’ Katherine said. Her voice was chilly. ‘Especially when you had more important things to do.’ She bounced Martha on her knee, and the child smiled. That sweet, easy grin which caught his heart every time.

Juliana was off somewhere, probably playing with her friends in the churchyard, and Richard was likely asleep in the solar. Ever since his birth he’d been a weak, sickly child, so close to death a few times that the priest had administered the last rites. Rest seemed to help him, but they both knew he would probably leave this world before too long. The knowledge hurt; it was like a knife forcing its slow, agonising way into his heart. But it was God’s will, something beyond his control. All he could do was accept it when it happened.

‘You know I didn’t have a choice. I had to go.’

Her eyes flashed. She wasn’t giving an inch.

‘And what else does the coroner want you to do?’

He hesitated before answering. ‘Not him. My Lord l’Honfleur. They body belonged to his daughter Gertrude, the anchoress. He wants me to investigate her death.’

‘No!’ She slapped her palm down hard on the table and shouted the word loud enough for all of Chesterfield to hear. With Martha crying and squirming in her arms, she stalked off through the buttery, down to the end of the garden to stare at the wall.

John waited. But she didn’t return. Instead, she stood by the apple tree, running her free hand along the bark. They’d picked the last of the fruit only a week before. Richard had felt strong enough that day to climb up in the branches and toss the apples down into a basket as they all laughed and sang. A day to cherish when times grew dark.

He went to her, stood behind her and placed his hands on her shoulders. Softly, he explained it all, his lips close to her ear. She wouldn’t turn her head to look at him, gazing straight ahead as she stroked Martha’s hair.

‘The money will solve everything,’ he told her.

‘I daresay it will.’ Her voice was withering, full of scorn. ‘If you’re alive to enjoy it. Have you forgotten what happened the last time you did all this? You came a hair away from death yourself, John. Do you remember that you promised me you’d never do it again?’

‘I do,’ he agreed. ‘But I know those four coins I brought home today are almost all we possess. What else can I do?’

‘Maybe work will pick up.’

Gently, he turned his wife until she was facing him.

‘It’s September. There won’t be much more business this year. We both know how the roof leaks, that we need new slates. If I don’t do this, we’re going to have to sell one of the houses to be able to repair the other and stay alive.’

She knew it well enough. They’d talked about it time after time once their children were asleep. And he knew how much she hated the idea. She didn’t want to believe it. Katherine had grown up in the house on Saltergate. All the warm memories of her childhood lay within its walls. And this place… it was still full of old Martha and the love she had for them.

‘It’s dangerous work, husband,’ she said. ‘That’s what scares me.’

But her voice had softened; John knew she’d accept it. It was necessary. The reward… it would save them. It held out the promise of a good life.

‘I’ll be careful. I’ll go to the church and swear on the Bible that I will.’

‘You know I can’t stand you doing this,’ Katherine said, and he nodded.

‘I don’t like it, either.’ He took hold of her hand and squeezed it lightly. ‘I don’t want to, but what else is there? L’Honfleur has ordered me to look into it. I can’t tell him no, can I? I don’t have the power to refuse his commands.’ Katherine shook her head. Below her anger and pain, she understood the reality of life. ‘Just be grateful he’s willing to pay a fortune for it.’

‘Fifty pounds…’ She said nothing for a long time. ‘Do you really think he’ll part with the money?’

John thought about the look on the man’s face. The sorrow, the anger, the longing.

‘Yes,’ he replied, ‘I do. He seems as honest as anyone in his position. There are witnesses, too; the coroner and his clerk. And Strong is giving me fourpence a day while I work.’

‘How much do you trust them all?’

Very little; that was the answer. Trust had no meaning at all. But he didn’t say a word.

‘If l’Honfleur pays, we’ll be safe for years.’

‘If he pays,’ Katherine said. She frowned as she spoke. ‘And what happens if you don’t find the person who killed his daughter? Have you thought about that?’

Of course he had. It had begun to gnaw at the edges of his mind on the walk back from Calow. He hadn’t lied to the coroner and l’Honfleur; John knew he’d been lucky before. But luck could easily stop smiling. It was a fickle mistress; it shifted its favours. And if luck wasn’t with him… l’Honfleur had influence. He had money. If he was angry at the failure, he could do anything he chose and no one would ever question it. No talk of justice and law. A poor man’s death would be nothing. No one with a voice would even care.

• • •

Strong lived just beyond West Bar, outside the town itself, in a house he’d had built shortly before John arrived in Chesterfield. The timber frames were solid, standing square and true, the limewash freshly applied this summer. The windows sat sturdy in their frames, and the roof looked tight. Everything snug and neat. The work had been done by proper craftsmen, John thought. The place wasn’t especially large, there was nothing about it that shouted out the status of the owner. But everything looked exact, with no ragged corners or edges. It was considered and careful, like the man himself.

Strong’s father had been a merchant, selling wool from the hill farmers to the weavers up in York. The business continued after his death, run by a factor. Strong’s only involvement was to take the profit and enjoy his hunting and hawking. And for the last six years, his position of King’s Coroner in Chesterfield.