Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The Mystery Press

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

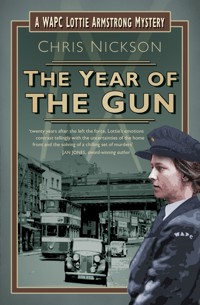

1944: Twenty years after WPC Lottie Armstrong was dismissed from the Leeds police force, she's back, now a member of the Women's Auxiliary Police Corps. Detective Chief Superintendent McMillan is now head of CID, trying to keep order with a depleted force as many of the male officers have enlisted. This hasn't stopped the criminals, however, and as the Second World War rages around them, can they stop a blackout killer with a taste for murder?

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 377

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

THE YEAR OFTHE GUN

For Margaret Clarke – thank you.

First published in 2017

The Mystery Press is an imprint of The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2017

All rights reserved

© Chris Nickson, 2017

The right of Chris Nickson to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7509 8516 1

Original typesetting by The History Press

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

Modern Crimes: A WPC Lottie Armstrong Mystery

‘This was masses of fun to read; with its incisive historicaldetail, colourful Leeds references and strong female characters.Lottie Armstrong is simply wonderful. I want to be Lottie.She is a force to be reckoned with.’

northerncrime.wordpress.com

‘Nickson’s rich, outstanding and complex characters and hisattention to historical detail will keep you riveted to what isalso a story strong on social comment and which brings tolife the city itself.’

crimereview.co.uk

‘No author has used the city of Leeds as a backdrop for crimestories so profoundly as Chris Nickson.’

crimefictionlover.com

Leeds, February 1944

‘WHY are there suddenly so many Americans around?’ Lottie asked as she parked the car on Albion Street. ‘You can hardly turn a corner without running into one.’

‘Are you sure that’s not just your driving?’ McMillan said.

She glanced in the mirror, seeing him sitting comfortably in the middle of the back seat, grinning.

‘You could always walk, sir.’ She kept her voice perfectly polite, a calm, sweet smile on her face. ‘It might shift a few of those inches around your waist.’

He closed the buff folder on his lap and sighed. ‘What did I do to deserve this?’

‘As I recall, you came and requested that I join up and become your driver.’

‘A moment of madness.’ Detective Chief Superintendent McMillan grunted as he slid across the seat of the Humber and opened the door. ‘I shan’t be long.’

She turned off the engine, glanced at her reflection and smiled, straightening the dark blue cap on her head.

Three months back in uniform and it still felt strange to be a policewoman again after twenty years away from it. It was just the Women’s Auxiliary Police Corps, not a proper copper, but still… after they’d pitched her out on her ear it tasted delicious. Every morning when she put on her jacket she had to touch the WAPC shoulder flash to assure herself it wasn’t all a dream.

And it was perfectly true that McMillan had asked her. He’d turned up on her doorstep at the beginning of November, looking meek.

‘I need a driver, Lottie. Someone with a brain.’

‘That’s why they got rid of me before,’ she reminded him. ‘Too independent, you remember?’ McMillan had been a detective sergeant then: disobeying his order had put her before the disciplinary board, and she’d been dismissed from Leeds City Police. ‘Anyway, I’m past conscription age. Not by much,’ she added carefully, ‘but even so…’

‘Volunteer. I’ll arrange everything,’ he promised.

Hands on hips, she cocked her head and eyed him carefully.

‘Why?’ she asked suspiciously. ‘And why now?’

She’d never really blamed him for what happened before. Both of them had been in impossible positions. They’d stayed in touch after she was bounced off the force – Christmas cards, an occasional luncheon in town – and he’d been thoughtful after her husband Geoff died. But none of that explained this request.

‘Why now?’ he repeated. ‘Because I’ve just lost another driver. Pregnant. That’s the second one in two years.’

Lottie raised an eyebrow.

‘Oh, don’t be daft,’ he told her. He was in his middle fifties, mostly bald, growing fat, the dashing dark moustache now white and his cheeks turning to jowls. By rights he should have retired, but with so many away fighting for King and Country he’d agreed to stay on for the duration.

He was a senior officer, effectively running CID in Leeds, answerable to the assistant chief constable. Most of the detectives under him were older or medically unfit for service. Only two had invoked reserved occupation and stayed on the Home Front rather than put on a uniform.

But wartime hadn’t slowed down crime. Far from it. The black market had become worse in the last few months, gangs, deserters, prostitution. More of it than ever. Robberies were becoming violent, rackets more deadly. Criminals had guns and they were using them.

And now Leeds had American troops all over the place.

‘Back to Millgarth,’ McMillan said when he returned, balancing a brown paper bag carefully in one hand. ‘If nothing’s come up while we’ve been gone, you can call it a day and get off home.’

Good, Lottie thought. The Co-op might have some tea left; she was almost out. She didn’t hold out much hope for the butcher by this time of day, though. At least it had been a bountiful year in the garden: plenty of potatoes and carrots and a decent crop of peas and marrows. One thing about all this rationing, she hadn’t gained any weight since it started. If anything she’d lost a little; clothes she’d worn ten years before still fitted.

She followed McMillan into the station and up the rickety wooden staircase, gas mask case banging gently against her hip. Why she bothered with one, she didn’t know; most people had stopped carrying them. On the landing a poster read Coughs and Sneezes Spread Diseases, the words so faded they were almost invisible. His office was the second one along a corridor where the old linoleum curled at the edges and the paint flaked under the fingers.

‘Quiet for once,’ McMillan said as he inspected his desk. ‘Close the door.’

‘Sir?’

‘Chop chop.’

She did as he ordered, then watched him reach into the paper bag and draw out two eggs. Real, fresh eggs. When was the last time she’d seen any of those?

‘Go on, take them. They’re for you. When I saw Timmy Houghton he gave me four. Or don’t you want them?’

Lottie scooped them up carefully, swaddled them in a handkerchief and placed them in her handbag.

‘Of course. Thank you.’ She didn’t know what to say. He had a habit of doing things like this. A little something here and there. A pair of stockings, some chocolate. Even a quarterpound of best steak once that tasted like a feast. In the three months she’d been working for him she felt spoilt. It was his way of thanking her.

At the bus stop she cradled her bag close, miles away as she dreamed of the eggs, maybe with a sausage and some fried bread. The kind of breakfasts they had before the war. So many things had changed after Chamberlain spoke on the radio. Most of all, her life: two days later Geoff was dead from a sudden heart attack at work.

He’d left good provision for her. The man from the Pru came and explained it all. Insurance would pay off the mortgage on the house they’d bought in Chapel Allerton. There was an annuity as well as a pension from his job as an area manager at Dunlop. She’d never want for anything.

Her life was comfortable. Even Geoff’s death, even the war, couldn’t seem to shake her out of it. She was sheltered, numb. Lottie burrowed into it, hid in it. She was just too old to be called up for war work. Everything seemed easier that way. Until McMillan knocked on her door and turned her life upside down.

And she couldn’t remember when she’d been so grateful.

‘DON’T take your coat off,’ he said as she walked into the office. Half-past seven, growing light, but with a bitter, miserable wind in the air. What she wanted was to sit for a few minutes and warm up. She wasn’t going to have the chance.

Lottie gathered up the car keys and followed him out of the door.

‘Kirkstall Abbey,’ he said as she started the engine and felt the power of the Super Snipe’s engine.

‘Yes, sir.’

‘We have a murder.’

The old monastery was only three miles from the city centre, standing by the River Aire. It was hard to believe this had once been the middle of nowhere, she thought. But that was what they’d taught her at school; she still remembered it. They drove past the loud thrum and activity of a dozen workshops along the road, all going round the clock to win the war. Traffic moved in a steady flow.

The abbey had been a ruin for centuries, a shell of what it used to be just as surely as if Hitler’s bombs had landed on it. Lottie parked the Humber at the tail of a line of cars, close to the path that led down to the ruins.

A knot of men had gathered around one of the buildings, eight or ten of them together. She could pick out Detective Inspector Andrews with his stooped, crooked back, and Detective Constable Smith following on his heels like a puppy, the way he always did. A few uniforms, and then two men in army khaki. What were they doing here?

Lottie looked sharply over her shoulder at McMillan. ‘Who’s dead?’

‘An ATS girl,’ he answered. ‘You’d better come along.’

She walked at his side, hunched inside her greatcoat, looking around, taking it all in. She and Geoff had come out here regularly; he loved the history of the place. This was the first time since he’d died. For a second she half-expected to see his ghost wandering over the grass, rubbing the stones and staring up at the sky. But there was only the empty cold of winter.

‘What do you have for me?’ McMillan asked as they tried to shelter from the frigid wind.

‘She’s inside, sir,’ Andrews said, ‘as much as anywhere can be round here. In the chapter house, just off the cloister, through there.’ He gestured vaguely. ‘I thought you’d better see her before the coroner hauls the body away.’

‘Who found her?’

‘A woman walking her dog first thing. Scared the life out of her.’

McMillan nodded and rubbed his hands together against the chill. ‘Do we know who she was yet?’

‘Her name’s Kate Patterson. ATS private. She’s a kinetheodolite operator, whatever that is. Just twenty-three, poor girl. From Redcar. Stationed at Carlton barracks.’

The Chief Superintendent studied the ground. Too hard for any useful footprints. ‘How was she killed?’

‘Not so good, sir. A gun. Single shot. Up close, powder burns on her clothes. No other wounds that I can see, nothing on her arms, doesn’t look as if she put up a fight…’ Andrews shrugged helplessly. He was a man with too much on his plate already and dreading this.

A girl in the service, shot to death out here. That was as bad as it could be, Lottie thought.

‘Right, I’d better take a look. Which way?’

‘Follow me, sir,’ Lottie told him, leading him through the old church, its roof long gone, and down a pair of steps to the cloister path around a square of scrubby grass, then to the arched opening of the chapter house.

Such a bleak, terrible place to die, she thought. So bare and barren. A stone floor, windows open to the bitter east wind. Kate Patterson had probably come here with a man, seeking a private place for a little companionship, a few minutes of loving, and he’d killed her. At least someone had put a blanket over the body to offer her some decency.

McMillan pulled the cover away. Grunting as he knelt and steadying himself with one hand on the ground, he peered closely at the corpse. Lottie watched, standing silent, notebook and pencil in hand in case he had any thoughts. He simply moved around like a crab, then stood, took a torch from his overcoat and shone the light on the floor.

Stone. Not much to see. A dark patch of blood under her where flies and God knew what swarmed, even in this cold. Empty eyes staring up at the stone ceiling. It was damp enough to chill the bones; Lottie shuddered.

‘God,’ McMillan said finally. ‘Why?’

‘Are you giving the case to Andrews?’ she asked.

‘No.’ He shook his head. ‘This is the first girl who’s ever been shot to death in Leeds. She’s in uniform, too. I’m going to look after this one myself. The brass will insist on it. Anyway, Andrews already has enough to keep him busy until Doomsday.’ He glanced around. ‘Do you know this place?’

‘A little. It’s not as if it changes much.’

‘Sarah and I came out years ago when the children were small. She’s not one for history.’

His kids were grown now, one boy in the army in Burma, another air force ground crew, his daughter a WREN somewhere down south. He wore that nagging fear she saw on the face of all parents. She and Geoff hadn’t been able to have children; sometimes it seemed for the best.

‘Were you looking as we drove out here?’ she asked.

McMillan gave her a curious glance. ‘At what?’

‘We passed one pub down the road, but it looks like a local, not the type of place you’d go for a pick-up. There’s nothing bigger until much closer to town.’

‘What are you trying to say?’ He stared at her, eyes narrowed.

‘Whoever brought that poor girl here didn’t just stumble on the abbey by blind luck. There’s nothing nearby. And he certainly wouldn’t have found the chapter house without knowing the layout. No lights round here, never mind the blackout.’

‘The perfect place,’ he said quietly. ‘Especially if he intended to kill her. Far enough away from all the houses that nobody would hear the shot.’

‘That’s true,’ Lottie admitted. ‘But think about it: unless they really were at that pub down the road, they made a special trip. That means they’ll have taken the bus or a taxi.’

He shook his head in wonder. ‘You’ve worked that out in ten minutes. My men have been here for two hours. I knew there was a reason I wanted you working for me.’

‘It seems obvious, that’s all.’

‘Not to everyone, apparently. I’m going to need to talk to these Army and ATS people. Can you get whatever information Andrews has found? Tell him to send some of those bobbies who are milling around down to the pub and ask questions, and get others on a house-to-house round here. I want everyone working flat out on this.’

‘Yes, sir.’

By the time he returned to the car she’d read through everything and placed it on the back seat. Only a few sheets, the basics. She saw the black coroner’s van arrive and the men in their brown shop coats carry out the wrapped body, no expression on their faces.

‘Where now?’

‘You’re the one with the bright ideas this morning. I’m sure you read the bumf.’

‘For what it’s worth.’

He paused for a fraction of a second. ‘Did you see the body?’

‘I tried not to look.’ Lottie hadn’t wanted to watch but she’d been unable to turn away. Now the image was burned in her mind.

‘I don’t blame you. Shooting her… I don’t know what’s happening to this country. Why on earth would anyone kill a girl like that?’ In the mirror she could see him staring out of the window and chewing on the flesh around his thumbnail. ‘You know, something did strike me. She was lying on her back. Her head was pointed towards the – what did you call it?’

‘The cloister.’

‘Yes. So whoever was with her was deeper inside that room.’ He was silent again. ‘Don’t mind me, I’m just thinking out loud. I’ll have the evidence boys go over that place with a fine-tooth comb. With a little luck we can find the cartridge. The post-mortem should tell us something.’ He glanced over his shoulder at the ruined stone tower of the abbey. ‘Do you think there’d be anyone in a place like that at night?’

‘I don’t know.’ Lottie answered, then thought. ‘Could be a tramp, I suppose.’

‘That’s possible,’ McMillan agreed. ‘Once we’re back at the station I’ll start asking around. It’s worth a shot. If a tramp was there he might have seen something.’

‘The newspapers are going to play all this up,’ she warned.

‘No, they won’t,’ he told her. ‘Not yet, anyway. You won’t read anything about it. A quiet word and it’ll be hushed up. Bad for morale.’

‘I see,’ Lottie said doubtfully.

‘Don’t you agree?’

‘I’m not sure.’ It was an honest answer. If you couldn’t trust the papers, who could you believe? Surely people could handle the truth. ‘Millgarth?’

‘Soon as you can.’ He stared out of the window as she drove along Kirkstall Road. Business and factories, and on the other side stood houses, rising up the hillside towards Burley. Nowhere to attract the young looking for some fun and games.

She’d learned to drive twelve years before, when Geoff sold the motorcycle and sidecar and bought a car. A Morris Minor first, then the Morris Eight once they started selling them. Lottie loved the freedom it brought. Lock up the house and go anywhere you want; it was perfect. But she’d never dreamt she’d become a driver. There’d been so much in the future she couldn’t anticipate.

She heard the rustle as McMillan glanced through the papers.

‘She was in a barracks in Headingley,’ he said.

‘Maybe her friends will know where she was going.’

‘Let’s hope so.’ He sighed. ‘We’ve got enough with the Jerries and the Japs trying to kill our troops. We don’t need our own people doing it, too.’

On the way back into town she passed a pair of bombed-out buildings. Almost three years since the last raid and they hadn’t been pulled down yet. Leeds had been lucky; not even a dozen visits from the Luftwaffe and very little damage. Not like the footage of London and Liverpool and Hull that she’d seen in the newsreels. Or the devastation that had once been Coventry. And she was grateful.

There were two other WAPCs in the canteen. Lottie carried her tea over to join them. Helen was a telephonist, handling the switchboard, while Margaret worked as a records clerk. Stuck in offices all day, they envied her the freedom of being a driver.

‘At least it’s never going to be boring,’ Helen said. ‘And you get to see what’s happening.’

‘All that fun out there in the cold and wet?’ Lottie said. She wasn’t going to mention the murder. They’d hear about it soon enough, anyway. ‘The heater in that car hardly works and I’ve been trying for a fortnight to get the garage to put on new back tyres. No rubber, that’s what they tell me.’ She shook her head from side to side. ‘Don’t you know there’s a war on?’

They began to giggle, ducking their heads together. Ten minutes later Lottie was sitting there alone as the others returned to work.

But they were right, it was a good job. She enjoyed working with McMillan, they had an easy relationship that had built over the years. For the most part the work was interesting. Her fifty-five hours a week passed quickly, almost before she realised it. And she was doing her bit. It was certainly more satisfying than the volunteering at the nutrition centre she’d done before.

But this was going to test her, she knew that. Kate Patterson’s dead face came back into her mind.

‘Tell DC Smith I want him to check all the taxi companies and see if they had a fare out to the abbey last night,’ McMillan said when she returned to the office. ‘If he can drag himself away from Inspector Andrews, that is.’

Lottie’s mouth twitched into a smile. If Smith stuck any closer he’d be following the other man home at night.

‘Yes, sir.’

‘After he’s done that he can talk to the conductresses on the Kirkstall Road buses. See if anyone remembers a young couple.’

‘Will you be needing the car again today, sir?’

‘Yes. I’m meeting Private Patterson’s CO at the ATS headquarters in an hour.’ His voice was quiet, very sober. ‘Then I’m going to talk to the girls she shared a room with in the barracks. I want you with me for all that.’

Standing back from Clay Pit Lane, Carlton Barracks looked cold and imposing, the Victorian brick black with years of soot. Lottie had never been inside; she’d never had a reason. It carried the air of an institution, everything regulated and ready to stamp out all traces of individuality. McMillan showed his warrant card to the sentry at the gate. Lottie eyed the rifle hanging from the soldier’s shoulder, polished and menacing.

She trailed behind the superintendent, through an office where a harassed lance-corporal muttered to herself as she rummaged through a stack of paper. A door was open and beyond it, an officer. She was a smart, alert woman in her early forties, hair neat and short, her uniform tailored, eyes an unusual deep blue, intelligent and questioning.

‘I’m Captain Hayes.’ She stood and extended a hand. ‘Private Patterson...’

‘We’re going to find whoever killed her,’ McMillan said before she could continue. Not a trace of doubt in his voice.

The captain paced behind her desk. She wanted to understand, Lottie thought, to try to make sense of it all. To give it some order and reason. But how could you, when it was so senseless?

‘I just don’t see…’ the woman began, then, simply: ‘Why?’

‘We don’t know yet.’ His voice softened. ‘I’ve been doing this job for a long time and it’s always bad when there’s a woman involved. I’m sorry, I truly am. Have you told the other girls what happened?’

‘Just that she was murdered. That was hard enough. I didn’t tell them how.’

‘Thank you. I need that to stay quiet. You understand.’

Hayes nodded. ‘I’ve never lost any of my girls before, Superintendent. I didn’t imagine I would, not up here. This is supposed to be a safe posting.’ She gestured at the pen and paper on her desk. ‘Now I have to write to her parents. I don’t even know what to say.’

‘It’s hard, I know that,’ he agreed. ‘I served in the last war.’

Hayes nodded. ‘Do you have any clues at all?’

‘Not so far. We’ve just started. We will, though. And I’ll make sure her killer hangs.’

‘Thank you.’ She tried to smile but there was nothing behind it. ‘I prepared her file for you.’ The woman hesitated. ‘I hate to speak ill of her when she’s barely dead, but I’d better tell you: Private Patterson wasn’t exactly a model ATS girl. She’s been up on charges several times: reporting back late to barracks, sometimes drunk.’

‘I understand she was a kinetheodolite operator?’ McMillan asked, and the woman nodded. ‘What’s that?’

‘It’s an instrument that lets us track the trajectory of shells,’ she explained. ‘Quite skilled work. Very specialised.’

‘Was Patterson good at it?’

‘Very. That’s why I was willing to tolerate a lot from her. If her behaviour had been better she’d have been a corporal by now.’

‘Do you have the girls from her barracks here?’

‘I do. They’re waiting in the canteen, the far side of the square.’ She pushed the folder across the desk. ‘This is a copy for you.’

‘Interesting woman,’ he said. They walked around the edge of the square as a sergeant-major with a voice that could reach across the Pennines was putting recruits through their drill.

‘Sounded like she was trying to appear concerned when she didn’t really have a good word to say about Kate,’ Lottie said.

‘She did make Patterson seem like a bit of a wild one, didn’t she?’

‘Maybe her friends can tell us more.’

They were gathered at the far end of the canteen, three young women, heads close as they talked, sadness in their eyes.

‘You get the teas, I’ll make a start,’ McMillan said, and passed her a sixpence.

By the time she arrived he was already talking to them. The girls all had that pale, sober beauty that sorrow brought. Losing a man overseas was one thing; that was the risk of war. A friend murdered in the safety of home was entirely different. Too close, too real.

‘She always got to know about parties and that,’ a blonde woman with a Birmingham accent said. Her fingers twitched at a cigarette. ‘If she was going somewhere you knew it was a fun place. Kate was like that.’ She glanced at the other faces, receiving nods of confirmation. ‘She didn’t deserve anything like this.’

‘Did she have someone special?’ McMillan asked. He took out a packet of Four Square cigarettes and offered them round.

‘No,’ a brunette with a hard face told him. ‘She didn’t want none, neither. Lost her fiancé in North Africa a couple of years ago and decided she wasn’t going to get tied down again. Not until it’s all over, anyway.’

‘Was she a popular girl?’ Lottie wondered, and the eyes turned to her.

‘How do you mean?’ the blonde asked.

‘With the other girls. With men.’

The three girls looked at each other and began to laugh.

‘Blokes couldn’t get enough of her,’ the brunette said finally. ‘She knew what she wanted, if you get what I mean.’ She blushed slightly. ‘I know she’s dead and that, but it’s the truth.’

‘She liked to live up to her reputation, too,’ the blonde added with a smirk.

‘What did the other girls here think about that?’

A shrug as a response.

‘She didn’t care.’ The last girl spoke slowly. She looked almost too young to be in uniform, still very thin, her skin smooth, features not yet fully formed. Her face was pale, as if she’d been crying. But her voice sounded older, wiser. ‘That was the thing about Kate, you see: she didn’t give a monkey’s. She was good at her job, but as soon as it was over, she was out to enjoy herself. Whoever wanted could come along.’

‘And did you?’ Lottie watched them all. ‘Go along, I mean.’

‘Sometimes,’ the brunette admitted. ‘She’d be off on her own if no-one else was interested.’

‘What about last night?’ McMillan asked, looking at their faces. ‘Did any of you go out with her then?’

‘I took the bus into town with Kate.’ The young one again. ‘We both got off on the Headrow.’ A long silence, then she spoke with a catch in her voice. ‘That was the last I saw of her.’

‘Did she say where she was going?’

‘No. I don’t think she knew. She just wanted to be out and doing something. Feeling alive.’ She realised what she’d said and her face crumpled.

Feeling alive. Lottie let the words echo in her mind. Treasure the moment because who knew if there’d be another. Like so many these days. Who could blame them? It had been the same the last time around. Grasping those few minutes, knowing they couldn’t last.

Even if the Allied landings in Italy had put the first scent of victory on the air, the end was still a long way off. Plenty more would die before any armistice.

‘What about you?’ Lottie asked. ‘Where did you go?’

‘I was meeting a chap. We went to the Odeon, saw To Have And Have Not. It’s very steamy.’ She reached into the breast pocket of her uniform. ‘This was in Kate’s locker. I thought it might be useful.’

An address book. It might be valuable. Lottie took it.

A few more questions but no more information they could use. A pair of detective constables would go through the rest of Patterson’s belongings.

‘Kate sounds like she was desperate to be the life and soul,’ Lottie said as she drove cautiously out of the barracks.

‘Or she was drowning her sorrows,’ McMillan grunted.

IN the office she dropped Patterson’s ATS file on the tottering pile of papers. That was the thing about a murder case: in just hours the paperwork grew like Topsy. But it was still too soon for the results of any searches or the post-mortem.

‘I’ll fetch us some tea,’ Lottie offered and McMillan nodded absently as he started to glance through the reports.

‘No, wait,’ he said before she’d reached the door. ‘We’re going straight out again.’

‘Him?’ Lottie asked. ‘He’s got to be sixty-five if he’s a day.’

‘His name’s George Chadwick,’ McMillan told her. ‘And I doubt there’s anyone who knows this area better.’

She’d parked by the blue police box on Kirkstall Road. They could see the constable approaching. He looked sound enough, with a firm, easy gait, but the bushy white whiskers, thick moustache and the deep lines on his face gave away his age. McMillan rolled down the window.

‘George. Over here.’

The bobby squinted, trying to make out who’d spoken, then his face broke into a wide grin.

‘Mr McMillan. Not seen you in donkey’s years, sir.’

‘I heard you were back for the war.’

‘Colin Selby joined up. I wasn’t doing much and me missus wanted me out of the house more, so I became a Special Constable…’ He shrugged and gave a hearty laugh before his face turned sombre. ‘I hear you want to talk about tramps out this way.’

‘I’ve got an ATS girl who was shot to death at the abbey. I wondered if anyone dossed down there who might have heard or seen anything.’

‘I heard about her. That’s…’ He couldn’t find the words, shrugged his shoulders and collected himself. ‘There are two who spend time out there. I’ve been looking for them since I got the message but there’s neither hide nor hair today.’

‘Is that normal?’ McMillan asked. He had his head cocked, listening attentively. Lottie was paying attention. The copper might be knocking on a bit for the beat, but he sounded sensible enough.

‘They come and go,’ Chadwick said. ‘No telling really. There’s Harry Giddins, he’s scared of his own shadow. Took bad in the last war and never got himself right again. And Leslie Armistead, he’s as gentle a soul as I ever met. If you want my opinion, sir, they’ve probably made themselves scarce, what with all the attention round there.’

‘I’ll still need to talk to them both. Find out if they saw anything.’

‘Fair enough, sir.’ The constable nodded. ‘I’ll try to track them down for you this afternoon. You might do better if I’m there when you question them, if you don’t mind me saying so. They trust me.’

McMillan smiled. ‘I can probably arrange that. Call in as soon as you find them.’

Lottie turned the car and began the drive back into Leeds.

‘Back in 1912, George Chadwick took on a man armed with a knife,’ McMillan began. ‘Chased him for a mile then brought him down. Stabbed in the arm. Joined the Leeds Pals, survived the Somme. Wounded twice, decorated for gallantry. I’ve plenty of time for someone like that.’

‘I’m sorry.’ She felt chastened. ‘I didn’t know.’

‘I trust his judgement.’ He lit a cigarette and stared out of the window.

They passed a US Army lorry that was parked at the side of the road. Three men stood at the back, laughing and smoking. They all looked so… Lottie struggled to find the right word. Fresh. Clean. Scrubbed.

Happy.

That was it. They always seemed to be smiling, as if they didn’t have a care in the world and nothing could touch them. So different from the British, ground down by the years of war, rationing, walking around with grim, grubby determination. Hanging on. There’d be time for joy after the job was done.

She was waiting. Only to be expected, she supposed, working for a senior officer, although she’d rather be doing something than sitting on her behind. Lottie had never been one to relax easily.

She’d learned to carry a book with her, something from the library. Along with the newspaper, it filled the time. A Peter Cheyney thriller, or maybe James Hadley Chase. Georgette Heyer if she was in the mood. And there was always Daphne du Maurier – she’d read Rebecca seven times since it was published. But McMillan always seemed to interrupt just as things were becoming interesting. As if he knew and wasn’t going to let her become too comfortable.

‘We’re going to Headingley,’ he announced as she slipped a bookmark between the pages. The Power and the Glory would have to wait.

‘Whereabouts?’ she asked as she nosed the car through the traffic on the Headrow. Blast walls protected the large glass doors of Lewis’s, and the huge water containers of the National Fire Service still stood on the central island in case of air raids. They were empty now, rusting, unused; please God they’d never be needed to put out fires.

Lottie turned on to Woodhouse Lane, then out past the university and the moor. The sky was grey, the threat of sleet in the air. Past a rag and bone man, trundling along, the horse drawing his empty cart. But who threw things away any more? The government had taken everything worthwhile.

She turned on to Shire Oak Road and within a few yards she was in a different Leeds. Large, spreading trees. Big houses, expansive gardens. Room to breathe, it seemed, nothing cramped. The humps of Anderson shelters showed in a few places, disguised until all that was visible was mounds of sod.

‘We’re looking for a house called Woodmarsh,’ McMillan told her. ‘Strange name.’

She scanned the words carved into the stone gateposts. No iron gates now, of course; they’d long since been fashioned into Spitfires or Hurricanes. Finally she spotted it, at the far end of the street, set apart from all the other buildings, looking down the hill over Meanwood Valley.

The house looked abandoned, in need of attention. She counted four slates missing from the roof, the garden was overgrown, and weeds poked through in the drive.

‘Park on the road,’ he told her.

‘But it looks empty.’

‘I know.’ He was smiling. ‘Come on.’

The front door was unlocked, the wood warped. He pushed at it with his shoulder until it gave, swinging open. Inside, the rooms were bare boards and empty walls. Anything that could be carried away had long since gone.

The house smelt of decay. But there was more. An empty gin bottle that had rolled into a corner. A pair of knickers tossed on a windowsill, a torn handkerchief bunched up against the skirting board.

‘What is this place?’

‘Someone came here to enjoy themselves,’ he answered wryly. ‘Can’t you tell?’

‘It looks… miserable.’ How could anyone find pleasure here? Lottie glanced around. A couple had found an empty house for a good time. ‘I don’t understand. What does any of this have to do with the Patterson case?’

‘We had a telephone call from a neighbour this morning,’ McMillan told her. ‘He said he glanced out about midnight two nights ago and saw someone carrying a girl in his arms to a Jeep. She looked as if she was passed out. His words,’ he added carefully. ‘That’s why we’re here.’

‘I still don’t understand how that connects to Patterson. Was she wearing an ATS uniform?’

‘He didn’t see. I don’t know, it’s a hunch,’ he said, as if that explained everything. ‘As soon as I saw the message I got a feeling in my gut. I just wish he’d rung when he saw it happen, instead of thinking it over for so long.’ McMillan rolled his eyes in frustration. ‘The public.’

‘There’s not too much to see in here now.’

‘Enough, though. We’ll take a nosey around,’ he insisted. ‘I’ll look in the bedrooms if you want to search here and out in the garden.’

The clean-up must have been quick, probably done in the darkness. A few items still remained. Not just the abandoned knickers, the handkerchief, and the empty bottle. Cigarette ends. She stirred them with her fingernail. Player’s. Lucky Strikes. People had been here, they’d had sex. But it didn’t look like the aftermath of a party. Outside there was nothing. A rusted spade, a fork, and an empty cup, all caked with dirt as if they’d sat there for months.

McMillan’s tread was heavy on the stairs. At the bottom he turned and looked back up, as if he was assessing something.

‘What is it?’

‘Nothing much. All I really found was this.’ He held out a crumpled note.

It was a man’s handwriting; Lottie was certain of that. Small, cramped. An address on Lower Basinghall Street.

‘At least we have somewhere to go,’ she said. ‘But I’m still not convinced. I haven’t seen anything that says Kate Patterson was here.’

‘It’s just… call it copper’s instinct.’ He groped for the words to explain. ‘Sometimes you know. I’m going to get the fingerprint and the evidence crews out here.’

Lottie glanced at the crumpled underwear.

‘Was she wearing knickers when her body was found?’ The uniform skirt had been in proper order; impossible to tell.

‘No idea. It’ll be in the pathologist’s report. Put those in a bag and bring them along.’

She did as he ordered, picking them up with a pencil. Silk. Expensive. Not something you’d get at Woolworth’s with clothing coupons. She took the handkerchief, too.

‘I need to talk to the chap next door first,’ McMillan said. ‘See if I can get more from him.’

‘He said the girl was put in a Jeep?’ Lottie asked.

‘Yes.’

‘There are American cigarette ends on the floor. Lucky Strikes. British ones, too.’

‘Then the Yanks were involved. And if I’m right and Kate Patterson was here, you’d better prepare for some hands across the water.’

The neighbour was waiting expectantly outside his front door. He looked close to eighty, comfortably plump even on the ration, a yellow waistcoat bulging over his belly. The type who didn’t approve of a woman in uniform; she could see it in the glare he gave her.

That was fine. She could sit in the car, open her book, and spend a little time with Graham Greene and the whisky priest. As she sat, a tune popped into her head: Imagination. She’d heard it twice on the radio in the last week and now it wouldn’t leave her alone. She didn’t even particularly like it. She began to read, humming under her breath and wishing the song would go away.

It was impossible to park on Lower Basinghall Street without blocking the entire road. Even walking down it gave her the creeps. The buildings rose to block out all the light and warmth of the day; it felt like stepping down into a chilly cellar.

‘Number seventeen,’ McMillan said. Judging by the brass plates outside the main door, it was a warren of offices. Insurance, a commissioner for oaths, manufacturers’ representatives, a jumble of mankind scraping a living.

‘What name?’ Lottie asked.

‘It’s not written down. Just the address.’ He raised an eyebrow. ‘Well?’

‘Just a thought: maybe a cup of tea before we start. We can make a plan. We don’t even know what we’re looking for.’

He jingled the coins in his pocket and nodded, glancing again at the list of businesses.

‘Probably a good idea,’ he agreed.

At least the British Café in the crypt of the Town Hall did a decent cuppa. Strong enough for a spoon to stand up, plenty of sugar. A bunch of servicemen crowded round one of the tables, caps through the epaulettes, cradling the mugs lovingly as they talked. A woman walked by, her legs a curious brown colour, the stocking seam a suspiciously crooked line. Painted with diluted gravy browning, the seams marked in with eyebrow pencil. God, Lottie thought, that was vanity.

‘How do you suggest we approach it?’ McMillan asked. He lit a Four Square, holding it with fingers stained gold by nicotine.

‘Maybe someone at Basinghall Street has the keys to the house.’ She’d considered it as they walked. Something to do with business seemed the only feasible connection.

‘That’s possible,’ he allowed.

‘If it’s someone young, they might have been at the party.’

‘Good thought.’ McMillan nodded. ‘If there was a party. I’m not convinced it was as wild as that.’

‘What did the old buffer next door have to tell you?’

‘Evidently the chap who owned the house died a year ago. The will’s in limbo for now. One of the heirs is dead, the other two are off fighting. I’ll get someone to track down the solicitor and ask questions.’

Lottie ran her cup around the rim of the saucer. She knew what she wanted to say; finding the words was the hard part.

‘This seems to be an awful lot of work just for a hunch.’

‘We know someone was in that house,’ he told her.

‘Yes,’ she agreed slowly. ‘Someone. A man and a woman, maybe more, we can’t tell yet. And with a Jeep and the Lucky Strikes, one of them could well be American. But that’s all we know. Right now there’s absolutely nothing that links it to the Patterson murder. No evidence. Only your hunch.’

She felt better for getting it off her chest. He was a detective, he had a good record, but nobody was right all the time. At least they’d known each other long enough for her to be candid. ‘I’m sorry,’ she added.

‘No, you’re right,’ he agreed. He didn’t look annoyed. If anything, there was relief on his face. ‘See, this is why I’m glad I asked you to be my driver. You stop me getting carried away. You’re right: the feeling is all I’ve got. But I can sense it.’ He stubbed out his cigarette in the ashtray. ‘The P-M and the other reports won’t be in until late afternoon. I’ve nowhere to turn before them. And this feels right. That’s why we’re following it.’ He stared until she nodded her agreement.

He started from the top floor while Lottie worked her way up from the ground. Office after office of old men who looked expectant and hopeful when she opened the door. Each time she disappointed them. No one knew anything about the address on Shire Oak Road.

The last door. Finally. A Commissioner for Oaths. She didn’t even know what that was. Perhaps Ewart Hardy could tell her.

He was close to seventy but still with a twinkle in his eye, the Times spread across his desk. A clipped moustache, a good suit, old but cared for, a heavy beak of a nose.

‘How might I help you, young lady?’ An educated voice, crisp and clear. He looked like someone who’d retained an appetite for life and found it endlessly amusing.

‘I’m WAPC Armstrong, sir. We’re making a few enquiries in the building.’

He gestured at a chair. ‘Make yourself comfortable and enquire away. It’s a pleasure simply to have a visitor during the day. A lovely young lady is a bonus.’

Lottie smiled and sat, back straight. Who could turn down a compliment like that?

‘Are you familiar with Shire Oak Road, sir?’ The same question she’d already asked a dozen men. This time though, it brought a surprised gaze.

‘I should hope so. I live there.’

She felt a shiver along her spine. Something. She had something.

‘Whereabouts, sir? I know it’s a fairly long street.’

‘The cheap part, I’m afraid, down towards the shops on Otley Road,’ he answered with a bewildered smile. ‘Why, what’s going on?’

‘Do you know the empty house that looks out over the valley?’

‘I do. It’s funny, someone was asking me about it just last week.’

‘Oh?’ Lottie took out her notebook and pencil. ‘Would you mind telling me about it, please?’ she asked, trying to make it sounds like nothing.

‘An American,’ Hardy told her. ‘I think he was an officer. It’s so hard to tell with them, isn’t it? There was something on his shoulder, anyway, and a hat, not a cap. I was walking past, going to take the dog down on Woodhouse Ridge. He was standing by the entrance to the house, with his hands on his hips.’

‘What did he ask you?’

‘Who owned it, how long it had been empty, if it was for rent.’ He shrugged. ‘The usual things, I suppose.’

‘What did you tell him, sir?’

‘Not a great deal. I didn’t know much. It’s been vacant a year or so. I wrote down the address here for him. Said if he came in I’d see what I could do. But he never turned up.’ He paused, just a fraction of a second, then smiled. ‘You found my address there.’

He’d already put it together, not that it took a genius.

‘Can you remember anything about the man?’