5,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The Mystery Press

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

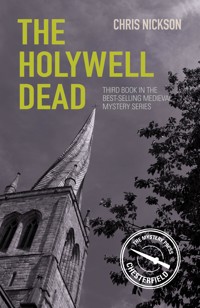

'Chris Nickson works his usual magic, populating late medieval Chesterfield with characters that are clearly of their time and yet jump off the page, vibrant and familiar. The icing on the cake (or the jeweled cover on the exquisite psalter) – a fiendishly clever puzzle. Highly recommended!' - Candace Robb, author of the bestselling Owen Archer mysteries 1361: John the Carpenter, married and soon to become a father, has plenty of work to keep him busy in Chesterfield. But when an elderly man in the town is found murdered with no clue as to why, the coroner calls upon John's mystery-solving expertise once again. However, this is a crime where nothing is as it appears. When the suspected murderer is found dead and a valuable Book of Psalms vanishes, John is suddenly embroiled in a string of crimes that threaten his own life and the safety of his new family.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

Praise for The Crooked Spire by Chris Nickson

‘The author powerfully evokes a sense of time and place with all the detailed and meticulous research he has carried out for this very suspenseful and well plotted story of corruption and murder.’

Eurocrime

‘[A] convincing depiction of late-medievalEngland make this a satisfying comfort read.’

Publishers Weekly

‘[Nickson] makes us feels as though we are living whatseems like a fourteenth-century version of dystopia,giving this remarkable novel a powerful immediacy.’

Booklist (starred review)

For Shonaleigh and Simon of Dronfield,the couple who have all the best stories.

CONTENTS

Praise

Title

Dedication

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Chapter Twenty-Seven

About the Author

Copyright

CHAPTER ONE

Anno Domini 1361

In the late May light he walked home along the dusty road. The old leather bag of tools slapped against his thigh with every step. His muscles ached from a long day’s work, but John the Carpenter felt content.

The job at the farm in Newbold was going well. A barn to complete, another four weeks of steady money, fourpence and a gallon of weak ale each day for his labours. At home his wife, Katherine, was waiting. They’d been wed during the winter, standing in the church porch while the snow fluttered down outside. A few words from the priest and it was done, then they walked back through a white Chesterfield to the house on Saltergate that would be their home.

Now the air was heavy with the smell of wild flowers, their bright colours dotting the copses and the hedgerows. The scent of honeysuckle caught his nostrils. He was happy, he thought. For the first time since he was a child, he believed he had a place where he belonged.

He glanced up and saw the tower of St Mary’s, the timbers of the spire rising higher and higher. It would be complete in just a few weeks and visible for miles around. It was work he could do quite easily, but there’d be nothing there for him. Not after last year.

Still, this was better. He took what carpentry work came along, big jobs or small. It was enough to get by. In the autumn of the year before he’d been offered the stewardship of a manor. A steward. A man of rank and position; how proud his father would have been. And yet … He’d thought long and hard about it, discussed it with Katherine and with Dame Martha, the widow woman who owned the house where he lodged before his marriage. In the end he’d turned it down, with his gratitude to Coroner de Harville for the offer.

In his heart he knew it was the right decision. What did he understand about farms, of crops and cows? He’d spent his whole life working with wood. He could feel the shape in a piece of lumber and bring it out with his hands. It was what he could do well. It was the thing he’d been born to do, his gift from God.

Since his refusal of the steward’s position the coroner had barely spoken to him, snubbing him when they passed on the High Street or on Saturdays in the market square. Let him be, John thought. The man had his own troubles, his wife still not recovered after the difficult birth of a son, according to all the gossip of the goodwives.

A cart passed, heading away from the town, and he paused to exchange greetings with the driver, then scooped up water from a stream and drank. It had been a warm, dry spring, and he was grateful: more time to earn money.

Back in March he’d begun cutting and shaping the timbers for the barn, choosing aged, good oak. It was a long, slow task, day after day with the saw and adze. He’d finally drilled and pegged the beams together, then put them up at the end of April, with the help of Katherine’s younger brother, Walter.

In the early evening, Chesterfield was quiet. The traffic of the day had passed. A pair of young girls hurried by, heads together as they spoke quickly. Noise came from the houses, but it seemed distant, muted and drowsy. A bee droned close to his head, then hummed away, out of sight.

He stood in front of their house on Saltergate. It still needed a little work, a patch of limewash to be replaced, a shutter to be re-hung in one of the windows. Nothing immediate; there’d be time for that later in the year, after his paid work was finished. Satisfied, he lifted the latch and walked in, past the screens and into the hall. Katherine had put fresh rushes on the floor, sprinkled with thyme that released its smell as he walked over them.

Her young sisters, Janette and Eleanor, were perched on the settle, one on either side of Dame Martha as she told them a story, the tale of an outlaw who only stole from the rich and gave what he took to the poor. They were listening, rapt, not even noticing as he passed.

Martha smiled and winked, never pausing in her words. He grinned at her and walked through to the buttery.

Katherine stood with her back to him, concentrating on stirring something in a bowl. Quietly, he crept up, sliding his arms around her waist and pulling her close to him.

‘John,’ she warned him with a gasp. But she didn’t resist, leaning her head back against his shoulder and giving a small sigh. ‘I didn’t know when you’d be back.’

It was true enough. As the days lengthened, he often worked until dusk had passed.

‘I missed you,’ he said, and she turned to kiss him. Sometimes, when he looked into her eyes, it was difficult to believe she was his wife, that this wasn’t some long, beautiful dream. Her lips tasted of cream; a tiny spatter of it remained on her cheek.

‘Martha came to see the girls so I asked her to stay for supper.’

That was the reason the old woman always gave, but he knew it was really to spend time with all of them. Somehow or other, she’d become a part of their family, welcome and wanted in this house. Katherine’s own mother had died the year before, her passing a blessing after her mind had gone. And his parents … his mother buried when he was young, and his father one of so many taken by the Great Pestilence, the leather satchel of tools all he had to leave.

‘Where’s Walter?’

‘He’s still out delivering messages.’ It was how her brother earned most of his money, delivering things and passing word around the town. She pulled back until he was at arm’s length, his hands still on her shoulders.

‘What is it?’ he asked.

‘The coroner was here after dinner. He wants to see you.’

He grimaced; whatever de Harville needed, it wasn’t good news. And after dinner? That was more than eight hours ago. The man would be waiting impatiently. The previous autumn John had helped solve a killing. He’d had no choice; he was still new in Chesterfield, a suspect in the murder himself. Finding the murderer had been the only way to clear his name. They’d invited the coroner to witness their marriage. He never came, but his clerk, Brother Robert, had slipped away to say a blessing over them.

And now de Harville was back with his demands.

‘Did he say what he needed?’ John asked warily.

A strand of dark hair had escaped from her veil. He brushed it back gently with his fingertips.

‘Old Master Timothy has died. That was the talk at the market this morning. They’ve raised the hue and cry for his servant.’

Timothy only lived a hundred yards away, in a grand house at the top end of Saltergate, a beautifully constructed building John admired for its jetting upper storey. But he’d never seen the man who owned it. People said Timothy been on the earth for eighty summers, surviving the plague and the famine many years before. He was supposed to be so frail that he could barely walk around his grand house.

The servant was the only one who ever came out of the front door. He was no young man either, the skin on his hands mottled with the dark spots of age, not a hair left on his head. But he carried himself erect and proud, as if he was happy to serve such a master. Nicholas; he recalled the man’s name. He didn’t seem the type to kill and run off.

‘Don’t worry,’ he told Katherine. ‘It’ll be fine. He probably only wants to annoy me.’ He didn’t believe it, but saying the words lightened his mood. He placed a hand over her belly. A small life was quickening there. She’d told him the week before, when she was far enough along to feel certain that the child wouldn’t vanish in a clout of blood. The only other person who knew was Martha, who’d beamed with delight when she was asked to be the baby’s godmother. ‘I won’t let him take all my time. I promise,’ he said.

‘Make sure he doesn’t.’ Her eyes flashed. Marriage hadn’t dulled her spark, and he was grateful for that. During her mother’s illness she’d run the house, fiercely protecting her family. Katherine was no scold, but she expected as much of others as she gave of herself. A few times he’d felt the sharp edge of her tongue when he’d been thoughtless. But making up after had been an even greater pleasure.

‘I will.’

‘And please, John, keep Walter out of things.’

‘If I can.’ It was the only answer he could give. Walter had helped him before, and the coroner knew it. If the man expected it … He looked at her helplessly. She smiled and stroked his cheek.

‘Try, please.’

He squeezed her hand and put his arms around her. He knew what she meant. He was a man with responsibilities now. And more on the way. He kissed her tenderly.

John placed his bag gently on the floor, out of the way so young feet wouldn’t trip over it. Before he’d left the job he’d cleaned and oiled all his tools, the way he did every day. They were a part of him, they’d served his father well, and with God’s good grace he’d be able to pass them to his own son, if he had the gift of working with wood.

He kissed his wife again, wiped the smudge of cream from her face, and walked down to the High Street.

The coroner’s house faced on to the market square, set at the back of a small yard with a stable to the side. He knocked on the door, waiting until a servant showed him through to where de Harville sat at his table, dictating notes to old Brother Robert, his clerk.

The coroner finished his sentence before looking up. His face had grown leaner and harder in the last few months, leaving him looking careworn and troubled. His fair hair was even more pale, his eyes colder.

‘About time, Carpenter. I’ve been waiting all day. I have a job for you.’

John stared at him.

‘I’m sorry, Master. People have ordered my services until the autumn.’ Whatever the task, he didn’t want it. He had his real work to do. If God smiled, perhaps the coroner would have some pity.

De Harville’s expression didn’t change. In the heat he’d stripped to his linen shirt, hose and boots, a thin green and yellow surcote tossed carelessly over a stool in the corner.

‘If I want you to do something, you’ll do it, Carpenter,’ he said bluntly. He picked up a knife lying on the table and stabbed the point hard into the wood. ‘You understand? I’m the King’s Coroner in this town.’

It was a battle he’d never had a hope of winning. He’d put up his small resistance, for whatever it was worth.

‘As long as you pay me,’ John said.

De Harville put his head back and roared with laughter. It was an ugly scourge of a sound.

‘You hear that, Brother? He thinks he can make demands.’

The monk kept his head lowered, his gaze fixed on the parchment in front of him.

‘King’s Coroner or not, Master, I need fourpence a day and my ale.’ If he had to do it, he’d be damned if he was going to lose money on this.

‘Done,’ de Harville agreed quickly. ‘Make a note of that so we can claim it later.’ He looked at John and shook his head. ‘You should have asked for more. The crown would have paid. Too late now. Be here first thing in the morning. We can let Timothy sit overnight. No one can do him any more harm now, anyway.’

CHAPTER TWO

John was up before first light, slipping out of the room quietly, leaving Katherine and the girls asleep up in the solar. He could hear Walter moving around in the buttery, preparing his food for the day. Bread, some cheese.

‘Can I come with you?’ he asked as John entered, yawning.

‘Not this morning,’ he answered kindly. The lad had helped him in the past, and even saved his life once. But he’d do what Katherine wanted, as long as it was in his power.

‘Why, John?’ Walter was smiling as he asked the question. He’d grown tall during the winter, bigger than his sister now although he was a few years younger. His dark hair was wild, his face so open it showed all his thoughts. The lad was still thin, not much more than a stick, but quick on his feet as he delivered messages around town. No one knew Chesterfield better. People thought the lad had turned simple after a blow on the head when he was young; in truth, he was anything but. Quick to learn and eager to please, he might stumble over words, but there was nothing wrong with his mind.

‘De Harville just wants me for now.’ He put a hand on the lad’s shoulder. ‘Don’t worry, I’ll need you soon enough.’ He hoped that wasn’t true.

But it was enough to make Walter smile.

‘I’m glad, John.’

For some reason the boy looked up to him. He was always eager to help, the way he had on the barn in Newbold and other jobs that needed a second person. John had tried to teach him carpentry and he’d mastered the basics. But no matter how willing, he didn’t have the natural feel for it.

He liked Walter’s company. On Sunday afternoons, as the church bell faded into memory, they’d often walk in the country, talking, discovering things. The lad had a sharp eye, he could identify the birds and the animals, where to find them and how to watch them unseen.

‘Stop,’ he whispered when they’d been out one day, halting John with a hand over his chest. ‘There.’ Slowly, he raised a hand and pointed. It took a while, but after a few moments John had been able to make out the stag in the trees, almost hidden in the branches. Yet Walter had spotted it straight away.

• • •

The coroner led the way through to the top of Saltergate. It was early, the sun barely risen, still a breath of coolness on the land.

John lagged behind, strolling beside Brother Robert. The old monk was limping, a small portable desk with its quills and parchment hanging from a strap on his shoulder.

‘How are you, Brother?’ He nodded at the coroner. ‘He won’t let you go back to the monastery yet?’

Robert shook his head. ‘He tells me I’m too valuable. I keep saying that he needs someone younger to keep pace with him, but he still won’t let me leave. With his wife ill, he’s prickly all the time.’ He gave a pointed glance. ‘I’d advise you not to test him, John.’

‘But the other way round …?’ He smiled.

‘Power does what it likes, you know that.’

‘How’s the child?’

‘Strong and healthy, praise God. He’s with the wet nurse.’ Robert’s eyes twinkled. He paused before adding, ‘You’ll be a father yourself, I believe.’

‘What?’ John stared in surprise. ‘How did you know?’

‘I’ve seen Dame Katherine,’ Robert said gently. ‘The glow on her face tells its own story.’

For a moment he was nonplussed, unsure what to say. Finally he just smiled and nodded.

‘October, she says. Pray it’s a safe birth for mother and child.’

‘I will,’ the monk assured him. ‘Don’t you worry about that.’

The coroner was waiting outside the house. The building looked as if it needed some work, as if it has been neglected too long.

‘I don’t have all day to spend here,’ he said sharply. ‘Old women move faster than you two.’

De Harville brought out a key and unlocked the door. Inside, the shutters were closed tight, just a little light coming through the gaps. The hall smelt of neglect and the sweet stink of death. John blinked, letting his eyes adjust to the gloom before he moved.

A rich man’s house, that was certain. A long table, a settle of good, carved oak, and a pair of fine tapestries hanging on the walls.

‘Up in the solar,’ the coroner said, and they climbed the stairs.

Here the shutters had been thrown back, showing a man propped up in a bed, a pillow behind him. The smell of putrefaction was stronger in the room; John held his breath and put a hand over his mouth as he approached the corpse. Maggots were already doing their work around the mouth, nose and eyes. Flies buzzed relentlessly. He swept them away, but as soon as his hand passed they returned. Brother Robert stood with his hands together and eyes closed, lips moving as he silently said prayers for the dead.

Timothy’s eyes stared sightlessly. Old hands rested on the blanket, the flesh wrinkled, dappled and gnarled by time. A full head of white hair, his linen shirt so ancient it had yellowed.

But there was no sign of violence. He looked as though he’d died in his sleep. John stepped back, still staring at the body. Then he turned to the coroner.

‘It looks like he died naturally.’

‘I agree,’ de Harville nodded. ‘But if he did, why would his servant flee? Tell me that, Carpenter.’

All John could do was shake his head. He glanced around the solar. A glazed window, the catch closed. A small chest for clothes stood in the corner, a night pot on the floor, still partly filled.

In spite of the heat, there was a thick cover on the bed, a sheet and heavy, rough blanket. Not too unusual, he thought; old bones loved the warmth and loathed the chill. He approached Timothy’s body again. Pulling back the covers revealed little. A man’s thin legs, most of the hair gone from them, the flesh very pale. Tenderly, he lifted the head from a pillow made of soft down.

His fingers could feel it immediately. A lump at the back of the skull. John’s fingers parted the hair, concentrating as he examined, working his way along slowly. It must have been a heavy blow. The skin wasn’t broken, but it had certainly been enough to kill an old man.

He stood back once more, thinking rapidly. The position of the blow … Timothy couldn’t have been sitting in bed at the time. Someone had taken the time to arrange him there, to try and make it look as if age had taken him.

‘Well?’ the coroner demanded.

‘Someone murdered him,’ John said finally. He began to walk around the solar, searching for the weapon. But there was nothing likely in the sparse room. ‘How did you even discover he was dead?’ he wondered.

‘Timothy owned three houses in Chesterfield,’ Robert replied. ‘One of his tenants came to see him. When no one answered the door, he tried the handle. It wasn’t locked. He came up here. As soon as he saw Timothy he called for the Master–’ he nodded at de Harville ‘–and we arrived and pronounced him dead. When the servant didn’t return, we raised the hue and cry.’

Simple enough, John thought, and obvious.

‘How long had the servant been with him?’

‘Since I was a boy, at least,’ de Harville snapped. ‘God’s balls, Carpenter, the man must have killed him and run off. Anyone can see that.’

‘But why now? If he’d been here for years …’

‘Who knows?’ he said. ‘Does it matter? We’ll find that out when we catch him. That’s what I want you to do.’ The coroner walked to the window and stared down at the street. The town was coming alive, the sound of voices, the grate of a cart’s wheels as it passed.

‘What do you know about the servant?’ John asked the monk.

‘Very little,’ he replied after a moment’s reflection. ‘Nicholas has worked for Timothy as long as anyone can remember. You must have seen him.’

John nodded. It was hard to imagine him as a killer. Especially one that seemed so calculating. Who could tell what lay deep in another’s mind? Maybe Timothy was a bad master and he’d finally had enough. His anger had risen and he’d committed murder. He wouldn’t be the first.

Then he stopped and wondered again. If this had been born from years of anger and resentment, would Nicholas have been satisfied with a single blow? And would he have taken the time to arrange Timothy in bed so carefully that it looked as if he’d died while sleeping? That was hard to believe.

‘Well, Carpenter?’ the corner asked. ‘What are you thinking?’

‘I don’t know yet, Master,’ he answered honestly and heard a frustrated sigh.

‘No ideas?’ he asked mockingly. ‘I expected more from you.’

John was about to reply when they heard the tentative footsteps downstairs, moving around slowly then climbing the stairs to the solar. They stood quietly, looking from one to the other.

He knew the face that emerged into the light. He saw it each Sunday, conducting the service at St Mary’s Church. Father Geoffrey. A man who spoke his Latin with painful slowness, his voice hardly louder than the mutterings and gossip that formed a constant murmur during the service.

The priest had dark hair that grew wildly from his scalp, streaked with grey here and there, and eyes that seemed to peer like an owl, as if he wasn’t quite certain what he was seeing. His surplice was simple, as clean as anything could be in Chesterfield, no more than a few stains on the dark cloth. There was no sense of wealth and riches about him, not like the churchmen John used to see every day when he lived in York.

‘God’s blessing, Father,’ de Harville said, and the priest looked around, taken by surprise.

‘God’s blessing on you, too, sir,’ Geoffrey replied. ‘Brother,’ he added with a small nod before turning his gaze on John. ‘God’s grace on you too, my son.’

‘Thank you, Father.’

‘What brings you here?’ the coroner asked.

‘When I came home last night, they said that poor Timothy was dead.’ He crossed himself as he stared at the body. ‘They told me you’ve raised the hue and cry for Nicholas.’ He glanced at the corpse. ‘His death looks peaceful enough.’

‘Don’t believe everything you see,’ de Harville said smugly. ‘Right, Carpenter?’

‘Yes, Master.’

‘You mean someone killed him?’ Geoffrey sounded shocked.

‘The servant. He’s run off.’

‘Did he …’ Geoffrey began, then gave a small, urgent cough. ‘Have you seen the psalter?’

‘Psalter?’ John asked.

‘It’s a book of psalms,’ Brother Robert explained, then looked at Geoffrey. ‘I didn’t know Timothy owned one.’

‘He did,’ the priest replied seriously. His eyes seemed to shine. ‘He showed it to me. Such beautiful illustrations, and all bound in leather. He promised it to the church when he died. It’s been in his family for generations but he had no one to leave it to.’

‘Where did he keep it?’ John asked.

‘In the chest. After he showed it to me, he had me put it back. It caused him so much pain to move.’

John was on his knees, lifting the lid, hands scrambling around inside the chest. A few clothes, all of them old and the worse for wear. Some ancient, cracked rolls of vellum. But no book.

‘It’s not here.’

‘Well, now we know who took it and why he killed his master,’ the coroner said triumphantly.

‘Nicholas …’ Father Geoffrey shook his head. ‘I find it hard to believe. He always seemed like such a loyal man.’

‘Loyalty’s only worth the pennies it’s paid,’ de Harville told him.

‘Did you come to see Timothy often, Father?’ John asked.

‘Every week. I gave him communion and heard his confession. I doubt he’d been out of the solar in more than a year. He couldn’t manage the stairs, you see. His legs weren’t strong enough to support him.’

‘How was his mind?’

‘As clear as ever. It was just his body that betrayed him.’ Geoffrey shook his head sadly. ‘He was waiting up here for death.’

But not in the way it happened, John thought. Not so violent. He looked around once more. No weapon, not even a sign that there’d been a struggle. Just the corpse in the bed. Someone had taken time here. No fear, no panic. And the psalter missing …

‘The psalter?’ he asked. ‘What does it look like?’

‘It’s about as big as a man’s hand,’ the priest said after a moment’s thought. ‘Easy enough to hide in a scrip or a pack, I suppose.’

‘What about money? Did Timothy keep a purse?’

‘Under the bed,’ the priest told him.

On his hands and knees again, John searched. There was only the dust on the wooden boards.

‘Have we finished here?’ de Harville interrupted.

‘Yes, Master.’

‘Good.’ The coroner moved to the stairs. Over his shoulder he said, ‘Come on, Robert, we have business.’ And to the priest: ‘I’ll leave you to take care of the body.’

There was nothing more to learn in the room. John knew what had killed Timothy and very likely who’d done it. Even why. All that remained was to find Nicholas, and that shouldn’t be too difficult. Where would an old man go? With a nod to the priest he made his farewell.

But he didn’t leave the house. Not yet. John prowled around the hall, pulling back the shutters to let in the day. A settle, a table and chairs, plate worth good money on display, the expensive tapestries, all of it covered with a layer of dust. And behind the hall, the buttery. Bread, cheese, oats to make oatcakes. Two flagons of ale. Off to the side was Nicholas’s room. It was as spare as his master’s, nothing more than a bed and a small chest that held a shirt and a pair of well-darned hose. Odd, he thought. If Nicholas had run, he’d surely have taken those. Burrowing further down, he found a small purse of coins. Stranger still. Why would he leave that?

The door at the back of the house was unlocked. He walked out into an ordered garden. Apple trees stood against the back wall, catching the bright morning sun. The soil was well dug and hoed, the first stirrings of plants poking through the soft earth.

The kitchen stood a few yards away, separate from the house in case of fire. Wood was stacked inside, a pan of pottage standing on the table next to a pair of clay bowls.

Against the far wall of the garden, as distant from the house as possible, lay a sprawling midden, flies buzzing noisily around it. John stood, stroking his chin. None of it made sense. Everything pointed to Nicholas as murderer and thief. But why hadn’t the man taken his few possessions? They’d be easy enough to carry. And even with Timothy’s purse he’d still have use for the coins in his chest.

The hoe was resting against the stone wall of the kitchen. He picked it up and started to poke at the midden, methodically pulling at the waste as he held his breath against the stench. It only took a few moments. The metal struck something and he carefully scraped the pile of refuse away.

He knew the empty face staring up at him. Nicholas the servant.

CHAPTER THREE

De Harville stood a few yards from the body and sighed.

‘God’s blood, Carpenter. I bring you to help and you turn everything upside down.’

He turned away and strode quickly back towards the house.

‘He hoped this would be simple, John,’ Brother Robert said sadly, staring at Nicholas. ‘What made you look there?’

‘The midden seemed too big,’ was the only answer he could offer.

‘May the Lord rest his soul.’ The monk made the sign of the cross. ‘Can you see what killed him?’

‘No.’ He hadn’t examined the body yet. Did it even matter how he’d died? Someone had murdered him and tried to hide the corpse. Surely that was enough?

The coroner was in the buttery. He’d poured himself a mug of the ale standing there. Still early and the day was already warm.

‘That boy,’ he said, ‘the one you used before. Your wife’s brother.’

‘Walter.’ It was the first time the man had ever acknowledged that John was now married.

‘Have him work with you.’

‘He has his own jobs.’

De Harville turned, fire behind his eyes.

‘It’s not a request, Carpenter,’ he roared. It’s an order.’

He waited before answering. It was the only resistance he could offer. He had no power.

‘Yes, Master. But he’ll need to be paid.’

The coroner nodded his agreement after a moment. ‘Two pence per day. That’s as high as I’ll go. The crown isn’t made of money.’ He slammed the mug down on the counter. They could hear the soft voice of Father Geoffrey, still up in the solar as he continued to pray over Timothy’s corpse. ‘Have him shrive the servant once he’s done.’ He shook his head in frustration. ‘Come along, monk, we have work to do.’

John watched them walk away, the brother limping slowly behind the coroner. Who could have killed Timothy and Nicholas? He had no ideas, nothing to point him in the right direction. What he needed was to learn more about Timothy. What he did, what enemies he might have made during his life.

• • •

It took a little while for Dame Martha to answer his knock. When she did, her eyes were bright, her veil brilliant white and her gown as fine as ever. But somehow she seemed a little more frail, as if she was slowly fading away. For the first time, he noticed the flesh stretched tighter over her bones and the way her skin seemed more transparent.

She’d spent her whole life in the town; few knew it as well. Here there had been joy and sorrow for her. The love of a long marriage. Time and the pestilence that had taken so many of her kin and friends. How does a life balance out, he wondered?

‘Come in, come in,’ she told him, guiding him to a stool. ‘So the coroner has you looking into Timothy’s death? Everyone said Nicholas did it and ran away.’

‘Then everyone’s wrong,’ he said and saw her astonishment. Martha loved to be able to give fresh gossip to the other goodwives in the marketplace. Now he could offer her something tasty to pass on. ‘Nicholas is dead, too. In the garden behind the house.’

‘May God give him peace,’ she said without thinking, then asked, ‘What happened?’

Her eyes were full of curiosity and he told her what little he knew.

‘What I really need is to know about Timothy,’ John told her. ‘And Nicholas.’

She poured ale for them both and sat, sifting through her memories.

‘Timothy was very handsome when he was young,’ she began. ‘He was older than me, but I still noticed him. I think all the girls were in love with him.’

‘Were you?’ She blushed slightly, but didn’t reply. ‘Did he ever marry?’ John asked.

She shook her head. ‘No, he never seemed interested. He rode and hunted, that was what he enjoyed. There was talk that he had someone, but it was never more than that. No one knew a name, even if it was true. He grew up in that house on Saltergate. It became his when his father died.’

‘So he had money.’

‘That goes back a long way in the family,’ she told him. ‘That’s what my mother always told me. Something to do with trading in wool. His father and grandfather before him. And Timothy carried it on.’ She paused. ‘Until his accident, anyway.’

‘Accident?’

‘His horse threw him,’ Dame Martha explained. ‘After that he couldn’t walk much. He sold off his business and spent all his time in that house.’ She chewed at her lower lip. ‘I doubt I’ve seen him more than twice in the last ten years. He had to use two sticks to get around. I think he felt ashamed to be seen like that. After he’d always been so strong and active. I know he owned a few houses around Chesterfield but I’m not sure how much he had besides that.’

‘No children anywhere?’

She shook her head again. ‘Not that I ever heard of. Not around here, anyway. He hardly seemed to notice women. He had his friends and that was all. And the pestilence took most of them.’

He swirled the ale in the mug and took another long sip.

‘How long has Nicholas been with him?’

‘Oh, it must be years and years.’ Martha brought a hand to her mouth, trying to think. ‘Long before the plague, I’m certain of that. Timothy’s parents died when he was about twenty. I suppose it was soon after that.’ She turned to look at him. ‘I’m sorry, I wish I could tell you more.’

‘What was he like?’ John asked. ‘Timothy, I mean.’

‘Pleasant enough when he was younger, I suppose. But he was always a little distant, as if he’d rather be somewhere else. He always rushed through his business to make time for his pleasure.’

‘And then his pleasure was taken from him,’ John said quietly.

‘It was, God rest his soul.’

‘Have you ever heard of a book of psalms in the family?’

‘No,’ she answered with a thoughtful glance. ‘Nothing like that. Why?’

He ignored her question.

‘What about Nicholas? Did you know him?’

‘Not really. You should talk to Evelyn.’

‘Evelyn? I don’t think I know her.’

‘Of course you do, John.’ She swatted playfully at his arm. ‘You repaired the hinge on her door back at the turn of the year. She’s the one who lives over by West Bar. One of Timothy’s tenants. Walks bent over. I often used to see them talking on market day.’

He remembered her now, one of Martha’s friends. They stood together at the side of the church nave with the other goodwives during the Sunday service.

‘You don’t miss much,’ he said in admiration.

‘I like to know what’s going on,’ she sniffed. ‘But since you’re here, there’s something I wanted to ask you. What are you going to do about Janette and Eleanor?’

‘The girls?’ He didn’t understand. ‘What do you mean?’

‘They’re very bright. They should learn to read and write.’

The thought took him aback. Reading? Writing? What would they need with that?

‘But why?’ he asked.

‘Because everyone should,’ she told him simply. ‘I already talked to Katherine. She agrees.’

He smiled. Even if he objected he had no chance.

‘Who’d teach them?’ John asked.

‘I would,’ she told him as if it was obvious. ‘Their numbers, too. I might as well be of some use in my old age.’

‘You’re not so old.’

‘And you’re not a good liar, John the Carpenter.’ Dame Martha smiled and tapped him on the knee. ‘It’s settled then.’

• • •

‘Yes, I know Nicholas,’ Evelyn told him. She shook her head. ‘I can’t believe he could have killed Master Timothy.’

‘He didn’t,’ John said.

She turned to look at him. Her face was lined with wrinkles, all her hair carefully tucked under her veil. Her wrists were like twigs, her fingers bent almost into claws by age. The years hadn’t been kind to her. Her back had twisted so she could no longer straighten it, and she shuffled more than walked. But her mind appeared sharp enough.

‘That’s what everyone said.’