Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

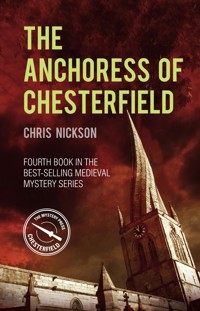

- Herausgeber: The Mystery Press

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

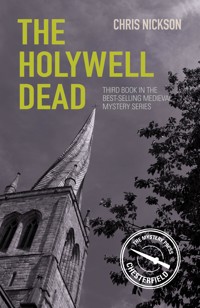

1364: The plague has returned and fear fills the air as the pestilence claims its first victims in Chesterfield. When the local priest vanishes, John the Carpenter believes the man is simply scared – until he discovers a body left in an empty house. Charged with finding the murderer by the coroner, John must dig deep into the past to discover who in the present has enough hatred to kill. But as the roll of the dead grows longer, can he keep his family safe from malign forces outside of his control? The third title in a gripping series following the best-selling titles The Crooked Spire and The Saltergate Psalter.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 374

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

For all the plague victims who lie nameless.

Cover photograph: © iStockphoto.com

First published 2017

The Mystery Press is an imprint of The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Chris Nickson, 2017

The right of Chris Nickson to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7509 8603 8

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CHAPTER ONE

May 1364

‘Do it like this,’ John the Carpenter said. He worked the chisel into the wood and eased it back out, then felt the straightness of the cut with his finger. The boy watched, absorbed, following each small movement. ‘Now you try it.’

Alan wriggled closer, so he could look down into the joint. He tested the sharpness of the tool’s edge with his thumb. Satisfied, he took a breath and began, aware of the line marked on the wood, knowing he couldn’t go beyond that.

‘Very good,’ John told him once he was done, and the lad beamed. Alan had just turned eight, still without the strength to do many things, but he was learning quickly. John had agreed to take him on, to teach him, because the boy had the feel for wood; it was deep in his nature. That was a rare gift. It spoke to him, told him what it needed. In time he’d be able to make a living from this, the way John did. For now, though, he needed to learn, to work his apprenticeship. The carpenter brushed the sawdust off his hose and shirt. A day’s work, well done.

Alan was mute. He’d never said a word since he was born. But he was quick, eager, with a sharp mind for his age.

The carpenter tousled the lad’s hair.

‘Come on, it’s late. I’d better get you home or your mother will wonder where you are.’

The shadows were starting to lengthen. Late May already. After a wet spring, where water puddled deep in the lanes and the fields and the world seemed filled with mud, the weather had finally turned warm and dry.

The crops would be late. Some were starting to grow, although much of the soil was still heavy. The farmers were worried. John had heard them at the Saturday market in Chesterfield, muttering and grumbling and shaking their heads.

But everyone was on edge. The dampness meant illness and bad humours. And a return of the plague. Already rumours had fluttered around of cases in towns away to the south or off to the north. Just talk, he hoped; there’d been nothing close to home. Pray God all the words were wrong. His father, a carpenter, had died in agony during the year of the great death, when John was just the same age as Alan.

No more of those horrors. Never again.

Alan was a fine worker, already cleaning the tools with an oiled rag the way he’d been shown. Slow and steady until he finished, putting everything away in the battered leather satchel.

This wasn’t a big job, just a pen large enough to hold twenty sheep. But it meant five pennies a day, the wage of a skilled man now. One of those went to Alan. From the way the boy picked things up so quickly, a few more years and he’d be off seeking his own jobs.

Soon enough it would be evening and the road into Chesterfield was already empty, all the traders and travellers gone for the day. Just their own footsteps raising dust. He’d be glad to be home, to see his wife and his daughter, Juliana. She was almost a year and a half old and more beautiful than he could have imagined any child could be. He’d hoped for a boy but as soon as he saw her it didn’t matter; she was so delicate and so full of life. It terrified him to think that the plague might return and take her. Or his wife, Katherine, her sisters, her brother. Even Dame Martha, the neighbour who’d moved into their house the year before, slowly growing too infirm to manage on her own. They were all his family. He wanted to protect every one of them.

John felt it as soon as they entered the town. Something was wrong. The place seemed too hushed, as if it was covered in a pall of sorrow. John escorted the boy to his house, then hurried home.

• • •

He held his breath as he opened the door and stepped into the hall. Jeanette and Eleanor, Katherine’s sisters, sat at the table with Dame Martha, practising their writing on pieces of slate. No sign of Walter, his brother-in-law, but that was no surprise; the lad would still be off somewhere delivering messages or with his friends.

Katherine was on a bench, nursing their little girl.

Everything was so ordinary, so normal. Had he imagined things?

‘John,’ Martha began. Her voice was a worried croak. ‘Have you heard?’

‘Heard what?’ He slipped the bag of tools from his shoulder, looking first at her, then to Katherine. ‘What?’ It was no mistake; he could feel the fear crawling up his back.

‘You know Jack the Fuller?’ She put her arms around the girls, drawing them closer to her.

‘Yes, of course.’ Always smiling when they met, full of bad jokes and a large laugh.

‘Two of his children, the youngest ones.’ She hesitated for a moment, as if not speaking could unmake it all. ‘Plague.’

He crossed himself, offering up a small prayer as he looked at his wife. Such helplessness on her face.

‘Sweet Jesu.’ But even as he spoke, his mind was working. Jack and his family lived down the hill, at the bottom of Soutergate, close to the bridge over the River Hipper. The air was always damp there, the ground boggy, especially after the wet spring.

Maybe it was the miasma in the air by the water. Maybe it was God’s will. He knew that in the end the reason didn’t matter. A man was going to lose two of his family, probably more. All the people around would be holding their breath and offering up their prayers to live.

Here, at the top of the hill where the air was clearer and the wind swirled around, would they escape? He knew, he remembered all too well what it had been like when he was a child. No one could forget. The black lumps in the armpits and the groin. The empty cries for help that nobody could give. And finally the stench of hell when they broke, then the sweet relief of death for the sufferers. Half the world had died, and many of those left alive and bereft wished they could be gone, too, because it seemed better than the devastation that surrounded them. Were those days returning? How could he keep his family safe? He reached out and took Katherine’s hand, looking down at Juliana. Her eyes were closed. She was content, oblivious to all the pain and panic in the world. Let her live, he thought. Let them all live.

• • •

Supper was quiet, everyone subdued and reflective. Walter came home, but he had no fresh word. No one else struck down, Jack’s children holding on to life.

Later, up in the solar, John stood by the small bed he’d made for his daughter, staring as she slept. He didn’t even hear Katherine approach until her arms were around his waist. The girls were asleep, with their soft snuffles. Walter was curled up, snoring. Downstairs, Martha moved around quietly; these days she needed little rest, it seemed.

‘It’s in God’s hands, you know,’ Katherine said softly in his ear.

‘Yes.’ But how could he put all his faith in someone who had allowed so many to die in agony just a few years before? Better, he thought, to fear and try to fight. Not that anyone could battle this. ‘I know.’ He turned and held her tight.

• • •

For three days, life in the town seemed to be suspended. No new cases and Jack’s children clung to the world. Each morning John collected Alan and they’d march out along the road to Unstone until they reached the farm where they were working. John kept an ear cocked for any gossip from travellers on the road. With evening they’d return to town, to the quiet and the desperate prayers for the future.

Then, on the fourth day, it changed. The news passed rapidly, not long after dawn: Jack’s children had both died, and there’d been another case in the night: Will the Miller’s widow, a woman who also had her home down by the river. Come evening, two more – Jack himself and a labourer with a tiny cottage on the other side of the Hipper.

No one from up the hill.

Yet.

No one said the word. No one dared breathe it. But all of them thought it.

John tried to concentrate on his work. It would keep everything else at bay. But whether he was using the chisel or the saw, the hammer or the awl, his mind kept wandering. Juliana, Katherine. Jeanette, Eleanor, Walter, Martha. Spare them all.

Twice he almost cut himself, then he had to stop himself shouting when Alan made a mistake, watching the boy flinch.

‘I’m sorry.’ He pulled a small wooden mug from the satchel and filled it with watered ale from a barrel before handing it to the lad. ‘It’s just my mood. Pay me no mind. I don’t mean it.’

In the middle of the afternoon John stopped and began to clean the tools. Alan gave him a questioning look, but the only answer he could offer was a shrug. He needed to be at home. He had to be with his family.

John stamped the dust off his boots and slipped the worn leather jerkin over his shirt. His hose needed to be darned at the knee again, he saw. But that came with the job, so much moving and crouching and kneeling. He hefted the satchel on to his shoulder and grinned at the boy. Alan beamed back.

They’d barely set foot on the road when he heard it. The slow toll of the bell from St Mary’s in town. Burying Jack’s children. The first of the Chesterfield dead. He’d spotted the gravediggers when he left that morning, working in an empty corner of the graveyard. How long before all that space would be full? How many more would die in the coming months?

It was only May. Summer, the worst season for the pestilence, hadn’t even arrived yet. This could linger, it could worsen. But surely it couldn’t be as bad as the black visitation they’d had before? Surely not...

A small elbow nudged him and he looked down. Alan was making quick signs with his fingers. It was a language of sorts they’d worked out between them. John watched, frowned, then watched as the boy repeated it all.

‘I don’t know,’ he said. At least Alan heard with no problem; it was just his speech that God had forgotten. ‘Believe me, if I knew when it would all end, I’d gladly tell you.’

• • •

Sunday morning and everyone gathered in church. Dame Martha stood off to the side with the other old goodwives. She always leaned on John’s arm when they walked now, but her smile lifted as soon as she saw the women she knew so well, all of them with their snow-white wimples and wrinkled faces. A chance to gossip and compare their aches and pains.

Katherine held Juliana in her arms. By now the girl could toddle well enough before falling over. Each time she tumbled, though, she cried as if the sky had fallen on her. Better to keep a grip on her here and let her gaze around, curious at everything.

The service was short. The priest, Father Crispin, seemed distracted. He was still new, in charge of the parish less than a year and they were still weighing him up, not certain yet what to make of him. Plenty of grey in his hair and today his eyes seemed to be full of fear. Just like his congregation, John thought. They all needed to feel God’s blessing today.

After the echoes of the final amen had faded, people gathered outside, sun dappling through the tall trees. Hardly a cloud in the sky but the air still felt close, as if it was pressing tight against his flesh. Not a good omen, John decided. He looked around, waiting for his wife as she talked to some of the other young mothers.

Then the coroner beckoned him over.

De Harville, preening like a peacock in a tunic of red and blue, his parti-coloured hose reversing the colours, all with boots the colour of dark wine. His wife was already on her way back to their house on the High Street, their young son at her side and a servant trailing after. He was the King’s Coroner here, and he wore the title with pride. Twice John had helped him find a murderer.

‘It’s not good news, Carpenter.’ His face was grim and his eyes tired. ‘Two in the ground and five more confirmed.’

‘Five?’ John brought his head up sharply. ‘I’d heard of three.’

‘Two more this morning. Someone came to tell me as I was walking here.’ At his side, Brother Robert, the old monk who served as the coroner’s clerk, began to mutter a prayer.

‘It’s in God’s hands.’ John echoed the words his wife had spoken, empty as they felt. He knew de Harville. A hard man when he chose, but he’d be as scared for his family as every other father in Chesterfield. Ready to cling to any hope, no matter how ridiculous or strange.

‘I’m worried about that priest.’ The coroner rested a hand on the hilt of his dagger.

The words took him by surprise. ‘Crispin? Why?’

‘In case he decides to run off. Didn’t you see him in there? He has the look of a coward.’

Maybe he was right; perhaps the priest was a frail man. Taking holy orders couldn’t change someone’s nature. It didn’t bring patience or courage or saintliness. He’d seen that during the two years he worked in York, a city full of men who claimed they were dedicated to God. But in the end they were all human. Some were tempted and fell. Some were venal. And a few were good.

‘Let’s hope not,’ he answered. They’d need someone strong to bind them all together. And someone to say the service of the dead.

‘We should go, husband.’ Katherine linked her arm through his, smiling. De Harville might possess rank but that didn’t mean he had her respect. She’d never cared for him and the way he used John to solve killings in the town.

The girls had scampered on ahead, Walter lumbering after them like a monster and delighting in their shrieks. God be praised, John decided, he was a lucky man to have all this. He just hoped it would all still surround him at the close of the year.

• • •

Evening. It was light outside, but the shadows were growing and the warmth of the day was beginning to drift away. Walter was playing nine men’s morris with Dame Martha. Katherine was darning and mending clothes, the girls sewing and cutting at her side. Juliana lay asleep, eyes closed, at peace with the world.

John sat with a mug of ale, lost in his thoughts, content. He sat up quickly at the knock on the door. Who could want him at this time? He looked at his wife. Her eyes were wide and frightened.

‘Brother,’ he said as he opened the latch. ‘Come in.’

Robert shook his head. He was breathing hard. These days walking even short distances seemed to exhaust him.

‘Father Crispin has gone. He wasn’t at the service tonight and he’s not at his house. The coroner wants you to help search for him.’

‘Me?’ He didn’t understand. ‘That’s a job for the bailiffs.’

‘He wants everyone looking, John.’ Brother Robert’s chest moved more slowly, the redness starting to disappear from his face. ‘He’s out there himself. You heard what he said about the priest this morning.’

He remembered, and it seemed as if he’d been right. But this wasn’t like the coroner.

‘What do we do if we find him?’

‘Bring him back.’ Robert lowered his gaze, staring at the ground. ‘He says a priest shouldn’t run away and he’ll be damned if he’ll let him.’ As soon as he spoke he crossed himself.

Those certainly sounded like de Harville’s words. He could hear the man’s voice and see him plunging his dagger into the scarred wood of his table as he spoke.

‘I’ll come,’ he agreed. A quick word, pulling on his boots, the hooded tunic and the old jerkin on top, and he was ready.

• • •

Full night arrived and they had to stop. They’d simply be blundering around in the dark. Even if the priest was there they’d never see him.

Dame Martha was still awake when he returned, sitting by the soft light of a tallow candle.

‘Did you find him?’

‘No.’ With a weary groan he lowered himself on to the bench. ‘He could be in Sheffield by now or halfway to Lincoln.’

‘His duty is here, John. In the parish.’

‘I know.’ Yet how could you force someone to stay? He took Martha’s hand. Her skin was like parchment, old, mottled with brown spots. Each year she seemed to grow more frail, her bones more brittle and her step less sure. But her mind was agile, and her tongue could be tart when needed.

‘Perhaps he’ll see sense,’ she said. ‘Maybe God will open his eyes.’

‘Let’s pray He does.’ He kissed her cheek and climbed up to the solar. He needed his sleep; the morning would arrive all too soon.

• • •

No word on Crispin as John walked over to collect Alan. A shower had passed through before dawn, enough to dampen down the dust for an hour or two. Fluffy, high clouds skittered across the sky, passing in front of a pale sun.

Not as warm today, he thought as they walked out towards Newbold. Farmers were on the road to town, ready to set up at the weekday market on the north side of the churchyard. Slabs of fresh-churned yellow butter, chickens in cages, early onions and beans, fragrant heads of wild garlic. He nodded his good morrows, exchanged a word here and there.

He was ready to work. Another day and they should have the sheep pen finished, then there were other jobs waiting, in town and around the area. Alan was learning more with each one. Walter helped when they needed extra muscle and a stout back, but wood didn’t call out to him; he was happier delivering messages all around Chesterfield.

The house sat a few yards back from the road. Until February old man Peter had lived there. But he’d died and the place had been empty ever since. Shutters closed, door locked. John noticed the place each time they passed, curious to what it might be like inside.

This morning, though, was different. The door hung wide, open to the sun and shadows. But there was no sign of life about the place, no sense of anyone busy within. Wait here, he told Alan, and handed the boy his bag of tools. Cautiously he approached the house. His hand gripped the hilt of his dagger, ready, just in case.

‘God’s peace be with you,’ he called out, but there was no answer. Just the birds singing in the branches. Inside, it took his eyes a few moments to adjust to the gloom, blinking until he could make out something in the corner. He moved closer, his knife out and ready. His palms were damp with sweat.

Then he realised what he was seeing and crossed himself. God save them all.

• • •

‘We’re searching for the priest and you find this,’ De Harville complained. Caught in its winding sheet, it had to be the body of a man. Big enough, broad enough.

‘I didn’t choose it, Master,’ John replied.

The shutters were pulled back and daylight flooded into the room. The bailiffs tried to keep their distance from the corpse, scared it could be another plague victim. Finally, tired of waiting, John stepped forward. If the man had died of pestilence, no one would have covered him so thoroughly. They’d have stayed far away.

Pray God he was right.

John knelt. The knife blade slid through the heavy cloth and he tore it further, ripping and shredding the fabric. For a moment he felt he couldn’t breathe. Then he stood and turned to de Harville.

‘Now we know what happened to Father Crispin.’

CHAPTER TWO

De Harville stared, saying nothing for a long time.

‘Slit it all the way open, Carpenter,’ he ordered finally. John sliced the heavy sheet until the body was exposed. Crispin was dressed, arms crossed over his breast. For all the world he looked like a man at peace, quiet and content in his death.

No wound that he could see, no strange smell of poison as he lowered his face towards the man’s mouth.

‘Well?’ the coroner asked.

‘I don’t know.’ He rolled the corpse on to its side. There it was, the small dark patch of blood on the back of his cassock, the tiny stain on the sheet beneath. ‘This is it.’

Whatever had made the wound was thin. Not a knife. Smaller, more like one of the needles the goodwives used. Yet bigger than that, longer, and very sharp, he thought, to pierce clothes and skin and to kill.

De Harville squatted, moving around to view the body from different angles, tongue between his lips.

‘Examine him properly, Carpenter. See what the body can tell you, then have the bailiffs take him to be buried.’

‘I have work to do—’

‘You have work to do for me.’ The man’s eyes flashed. ‘You were the first finder. That means a fine, returned when the murderer is found. A shilling.’

‘I have money at home.’

‘You’ve found killers for me before, Carpenter. You can do it again. Four pence a day.’

‘I usually make five. And my ale.’

‘Four’s my offer.’ His mouth curled into a smile. ‘Don’t try my patience. Or I could put you in jail until we find the killer.’

John stared at him. ‘That’s not the law.’

‘Carpenter,’ de Harville reminded him slowly, ‘I am the law.’

Beaten without even a battle. He knew it. A carpenter was nobody in this world, not when a man with rank and several manors to his name desired something. John had no power; he never would. He nodded his agreement.

‘Come to my house when you’ve finished.’ The coroner looked around. ‘Why does Robert have to grow so old? I need my clerk with me.’

‘You should get someone younger. Let the brother go back to the monastery.’

‘Not with plague all over the land. It’s safer for him to stay with me until it’s passed.’ He glared.

John waited until he was alone in the house before cutting through the priest’s clothes to expose his skin. Stabbed in the back, but it didn’t go all the way through; his chest was unblemished. Whoever did it must have pierced his heart. There was no sign of any other injury. The killer had even taken the time to close Crispin’s eyes as he wrapped him in the shroud. Someone who knew what he was doing, someone deadly and calm who felt no hurry or panic.

John paced around the room, examining the floor, pausing to feel the packed dirt with his fingertips. No trace of blood. The dirt was too hard and dry for footprints, but a path from the door could have been roughly swept, he decided, after the body had been dragged. Hard to be certain now, though; so many feet had walked over it.

The priest still wore a wooden cross around his neck, and a leather scrip hung from his belt. There was little inside, just a few coins and an old comb made from bone with some of the teeth missing. Not a robbery. Murder, pure and simple.

Why?

What did he know about Father Crispin? The man had arrived the summer before, after the parish had spent a twelvemonth with no one at the church, just a curate who travelled from Clay Cross to give communion twice a month.

Crispin was older, grey in his hair, so he must have spent time elsewhere. But he’d been a shy man, not given to small talk or idle chatter in the marketplace. No friends as far as John knew.

‘You can take him,’ he told the bailiffs as he left. They were waiting outside. Rough, hulking men, but good in a fight. ‘The church will look after him.’

• • •

De Harville had his feet up on the table, dictating to Robert who tried to keep up with his voice. They both stopped as the servant showed John into the room.

‘Well, Carpenter? What do you have to tell me?’

‘Very little, Master. It was carefully done and it didn’t happen where he was found. Nothing taken from him and that body was prepared. It was a very deliberate killing.’

‘Go on.’ The coroner stroked his chin.

‘I need to know more about the priest. Who he was, where he came from, what he’d done before.’ John shrugged. ‘It could be an old grudge.’

‘Brother?’ De Harville raised an eyebrow and looked at the monk. ‘How did he come to us?’

‘We wrote to the bishop to ask for a priest to replace the old one. After six months of begging he sent us Crispin.’

‘Did you know him at all?’

Robert shook his head. ‘I tried to talk to him, but he smiled and passed me by. It always seemed to me as if he didn’t have too much time for anyone here, as if in his heart he wanted to be somewhere else. He performed his duties and retreated home again.’

‘I’d like to look in his house,’ John told de Harville. The man gave a short nod.

‘I’ll come with you. I was there yesterday when we started hunting for him.’

It was a small stone building on the far side of the churchyard, with a door to the street and two expensive glazed windows, one for the hall downstairs and another for the solar above. The coroner chose a key from a heavy ring and turned it in the lock.

The room smelt musty and unloved, as if the inhabitant had been here reluctantly. John moved around, trying to fill himself with the sense of the priest. All he could feel was a man who lived a small life. Someone who wanted to be unremarkable, unnoticed. Hidden.

There was nothing of Crispin in the hall. Just the usual furnishings of any priest’s house – a table, a bench, a prie-dieu, candles in their holders, a Bible on the table. Above, in the solar, no more than a bed of old straw and a chest. Locked. He turned to de Harville. The coroner nodded.

He forced the hasp with his knife, pushing back the lid. A thick winter cloak of good wool lay on top, carefully rolled and scented with herbs to keep off the moths. It looked well-worn and old, John decided as he lifted it out, the nap of the cloth worn smooth. A pair of boots lay beneath, with heavy, solid soles, the uppers made from soft, expensive leather. He set them aside and returned to the chest.

It didn’t seem possible. John glanced at de Harville.

‘You need to see this, Master.’

A pair of knives, beautifully crafted, in heavily worked leather sheaths. A short sword in its scabbard. Not the tools of any holy man that he’d ever met.

‘What do you make of it, Carpenter?’

John sat back on his heels, still staring at the weapons in the chest.

‘I don’t know.’ In York he’d once heard of a soldier who’d become a monk. But never one who’d taken a priest’s vows. He glanced up at the coroner. ‘It seems that Crispin has a past. But there’s nothing here to let us know who he really was.’

De Harville drew out the sword, weighing it in his hand and making a few tentative cuts.

‘It’s a fine piece of work,’ he said admiringly. ‘Not cheap.’

John stood, his eyes roving around the solar. It was the same as the hall, nothing else of Crispin’s around, nothing that marked his presence here. What tiny life he had was all in that chest, and it didn’t speak of a peaceful man.

He tossed the straw of the bed, in case the priest had hidden anything. Then a closer search in the hall. Nothing. Maybe he simply had nothing to hide, no other possessions.

Outside, people moved around and the world seemed normal. The May sun shone and he felt the warmth on his face. The priest’s house had seemed chilly, as if spring had never quite reached the place.

A goodwife passed, clutching her basket, giving him a curious stare for a moment before turning away and forgetting him in an instant. John turned his head and looked back. A carrion crow perched on the roof of the house, its beak bobbing and pulling at something. Was that an omen?

‘What now, Carpenter?’

‘I don’t know. How can we find out who killed him if we don’t know who he’d been when he was alive?’

The coroner gave a tight nod. ‘I’ll write to the bishop. Meanwhile,’ he ordered, ‘I want you to start asking questions in town.’

• • •

Juliana pushed herself to her feet as he entered. She began to smile and tottered towards him. John scooped her into his arms, ducking to kiss Jeanette and Eleanor on the tops of their heads as they sat and span wool.

Dame Martha was working with Katherine in the buttery, brewing a fresh batch of ale. She assessed him with old, wise eyes.

‘Coroner’s work again, John? It’s all over town.’

He nodded, seeing his wife frown.

‘There’s not much to find so far.’ He reached out and squeezed Katherine’s hand lightly, an apology. But she knew he had no choice. If de Harville ordered, he had to obey. It was the way of the world. ‘What did you know about Father Crispin?’ he asked Martha.

‘Very little, I suppose,’ she answered after a moment as John tickled Juliana under the chin until she giggled; death and joy side by side. ‘He said the mass well enough but I don’t remember ever speaking to him.’

‘Could you ask the other goodwives? They might know something.’

‘I will.’ She gave him a pointed look. John let his daughter slide down his body. Martha took her by the hand and led her back into the hall.

‘I don’t want to do it,’ he told Katherine.

‘I know.’ There was a bitter undertone to her voice.

‘I found the body.’

‘And now you have to neglect your own work to do the coroner’s job?’

It was the same argument they’d had before. But they both felt the same, and the words were no more than her resentment at the way the coroner used his position. Finally he stroked her face.

‘I’m sorry,’ he said, ‘But I don’t think there’ll be much I can do. I don’t think the answers to this are in Chesterfield.’

‘There was another case of pestilence today,’ she told him, and suddenly he felt guilty. The priest’s body had driven everything else from his head.

‘Who?’

‘Elizabeth, the drover’s wife.’

The woman’s face sprang straight into his mind, round and red and cheery. They had five children, the oldest twelve, the youngest two, and she herded the little ones in front of her like a flock of sheep. Two of them worked but the youngsters kept close to her skirts. With her husband gone most of the time, taking his horse and cart between Sheffield, Derby and Nottingham, what would happen to them all?

The family lived close to the bottom of Soutergate, no more than a dozen yards from the bridge across the river. Praise God the plague hadn’t begun to climb the hill yet, he thought, then crossed himself.

‘Go,’ Katherine told him. ‘It’ll be dinner soon.’

• • •

He spent the afternoon asking questions around Chesterfield. But people had other things on their mind than Father Crispin. The new plague case brought more worry and fear. They drew into themselves and pulled their families close. They were wary of any stranger, and John had only been here for three years. He’d need more time to be trusted.

Still, no one had anything bad to say about the priest. He’d done his job well enough, yet none seemed to know him. Crispin had been remote, he’d made no attempt to be a part of the town.

Maybe it was simply the man’s nature, John thought later. He was sitting in the garden, holding a mug of ale, taking occasional sips. The priest had been a fighting man at one time. A successful one, to judge by the quality of his weapons. Perhaps it was that part of his history which made him wary of people.

‘John?’

He hadn’t heard Walter approach. But Katherine’s brother was light on his feet. He was taller than John now, fifteen years old and still growing like a weed. He earned a living by delivering messages and packages all over Chesterfield, reliable, swift, honest.

Some thought he was simple. When he was younger, someone had hit him hard on the head. Since then he’d spoken slowly, and sometimes he stumbled over words. But there was nothing wrong with his reasoning. Or his courage. John had learned that all too well.

‘Any more word on the victims?’ John asked.

The lad shook his head, the thick mop of hair dancing from side to side. The dust of the day still clung to his hose and tunic. ‘Do you need help looking into Father Crispin’s death?’ Walter had worked with him before. Saved his life, too, and put himself into danger. But the lad relished it. He liked the adventure and the excitement. His eyes glittered hopefully. He was young, he was immortal.

‘Not yet.’ He saw Walter’s face fall and told him what little he knew. ‘I don’t even have any idea why anyone would want to kill him.’ John eyed the young man. Walter was observant, so much a part of Chesterfield that people rarely noticed him. ‘What about you? Is there anything you can tell me about him?’

‘I-I-I saw two men at his door last month,’ he answered after a long pause.

‘Who were they?’ He could feel his heart start beating faster with the sense that this was something.

‘I don’t know, John,’ Walter answered. ‘I couldn’t see their faces.’ He hesitated, drawing the picture into his mind. ‘I think they were big men.’ He smiled quickly. ‘They had mud spattered on their legs and on their boots, as if they’d ridden.’

John was always astonished by the lad’s memory. He could conjure up images, still see things that had happened long before and pick out the tiniest details. That men had visited Crispin was interesting. If they’d ridden to town, then they would have stabled their horses somewhere. In the morning he’d discover more.

John chuckled. ‘You’ve helped me already.’

Walter frowned. ‘But I haven’t done anything.’

‘You have. You’ve done more than you know.’

• • •

In the darkness he sensed Katherine was still awake. Her small shifts in the bed, the uneven breathing even as she tried to be quiet.

‘Tell me it will be all right,’ she said softly.

Very gently, he squeezed her shoulder and pulled her closer. But he said nothing; he couldn’t lie to her.

• • •

‘Last month?’ The man stroked his chin. His clothes were filthy and stained. The whole stable reeked of manure. A boy moved a pile of it around with a besom, pushing it against a wall where it quickly gathered flies. ‘Aye, I remember now.’ He smiled, showing a mouth almost empty of teeth. ‘Didn’t stay half a day but they still expected the horses properly groomed and fed. Haggled over the price, too.’ He spat with disgust. ‘And then they didn’t want to pay.’

‘Where did they come from? Did they say?’

He shook his head. ‘Said no more than they had to. I’ll tell you something, though: they had money. Both of them on good beasts and better clothes than you’ll see round here.’

‘What do you mean?’ Strangers with money and good clothes? It seemed surprising that more people hadn’t noticed them. Men like that stood out and gossip was like gold.

‘Fine beaver hats and jackets with stitching on them.’

‘Stitching?’ John could feel his hopes rising. ‘A coat of arms?’

‘No.’ The man shook his head. ‘Not that. What do you call it... patterns.’

Embroidery, he thought. So much for that thought. Still, dressed like that they weren’t scraping for pennies. Men with some status.

‘No badges? No marks?’

‘No, nothing.’

Impossible to tell whose men they were. ‘How were they armed?’

The stableman grinned widely again. ‘I noticed that, right enough. A sword each and they both carried daggers. Hilts bound in leather and silver on the pommels.’

‘Silver?’ John asked sharply.

‘Sure as I’m standing here,’ the man said with a nod. ‘On the bridles, too. Like I said, fine animals and well-tended.’

‘What did they look like?’

‘They were big. Broad,’ he replied after a moment. ‘Hard eyes. They looked cruel. Arrogant, that’s it. One of them had a scar on his face. I’ll tell you this, Master, I’d not be wanting to go up against them.’

John slipped the man a coin, watched it disappear into his scrip, then said his farewells. It was a little more information. But did it help, or did it simply raise more questions than it answered?

What else could he do, though? He’d followed the only track he had, and that had come to nought. Until he knew more about Crispin, he was stuck. Finally he returned to the house, noticing a shutter that was just beginning to sag, kissed Katherine and picked up his bag of tools.

‘I’ll be back this evening.’

She looked surprised but happy. ‘No more mystery, husband?’

‘Not today, at least.’ He smiled, then his face turned serious. ‘No more word? No victims? I didn’t hear anything.’

‘No, praise God.’

But he knew it wasn’t over. Jesu save them, it had hardly begun.

• • •

Alan beamed to see him, pulling at his mother’s sleeve as she opened the door.

‘He’s missed you,’ she said. ‘I tried to explain but all he wants to do is go to work.’

‘That’s what we’re doing.’ He ruffled the boy’s hair. ‘A half-day’s labour. Are you ready?’

As they walked, Alan moved his fingers so quickly that John kept stopping him; he couldn’t understand it all.

‘Slower, slower.’

The boy was concerned that they might not work together any more because of the carpenter’s job with the coroner. He wanted to learn, he was eager; it was the first thing in life he’d ever done well, the first thing that had come as naturally as breathing.

‘Don’t you worry,’ John told him. ‘There might be interruptions but I’m not giving this up. It’s what I do. It’s what I’ve always done. You as well.’ As he spoke Alan nodded gratefully.

Only half a day’s work, but they filled every moment. More often now the boy could start on a task without being told; he realised what was needed and set to it on his own.

CHAPTER THREE

The days passed with work and the tolling of the church bell for the dead. New victims appeared in dribs and drabs. One, then nothing, two more, a gap just long enough for the town to begin to believe it might have passed, then another. So far all the victims lived close to the river; it was a single ray of hope.

John finished two small jobs. The next one was in town, shaping and erecting the framework of a kitchen behind one of the grand houses out past West Bar. A fire had destroyed the old one, and heavy, charred beams still lay on the ground, stinking of the blaze. It was simple work, cutting and putting up the wood before the mason came to lay the stone of the walls. He’d done it often enough before, here and in York. Most of the job was just sawing and shaping. Slow, repetitive, and with plenty of time to reflect.

There’d been no word yet from the bishop in Lincoln; he was certain that the coroner would have sent for him if any letter had arrived. John kept asking questions around the town, but it seemed as if no one in the flock had ever properly known their priest. A few had talked to him, arranging for weddings, for funerals, but none could say much about him. His past remained a mystery, and no one other than Walter seemed to have noticed his strange visitors.

Alan was cleaning the tools, wiping them with the oiled rag, when John heard the footsteps. Someone running. He turned, right hand ready to reach for his knife but it was Walter. For a terrifying moment the blood went cold in his body. Not plague at home?

‘Th-the coroner wants to see you, John,’ he said.

The carpenter took a long, deep breath. Small mercies. God be praised. ‘Thank you.’ He turned to Alan. ‘Finish the tools.’ He hesitated for a long moment, then said: ‘Take them home with you. Make sure you look after them.’

The boy smiled as if he’d been given the greatest gift in the world, making swift signs. Thank you, he’d take good care of them.

‘I know.’ It would be the first time since his father died that John hadn’t kept the tools close at night. He was surprised to realise that he trusted the lad so much.

• • •

De Harville was pacing angrily up and down the hall, his hands clenched into fists. Brother Robert sat at the table, pain flickering in small waves across his face.

‘What is it, Master?’ John asked.

The coroner looked at the monk and nodded.

‘We’ve heard from the bishop’s secretary,’ Robert began gravely, then started to cough. He held up his hand as John started towards him before taking a sip of ale to clear his throat. ‘He says that the bishop’s office is willing to tell us more about Father Crispin. But we need to go to Lincoln and have an audience with them.’ The words came out as a breathless croak and he drank a little more.

‘See them?’ He didn’t understand. ‘Why can’t they say it in a letter?’

‘I don’t know, Carpenter.’ The coroner held a pewter mug so tightly that his knuckles were white. ‘And now we have to go all the way to Lincoln to find out.’

We. ‘You know they’ll listen to you more than they would to me, Master.’

‘Of course.’ De Harville nodded, taking it as his due. ‘But I want you to come with me.’ He gave a dark, wolfish smile. ‘You can be good company on the journey and hear what they have to say.’

‘I can’t. I have work waiting here.’

‘Then it will just have to wait longer.’ He waved it all away. ‘We leave first thing in the morning.’

• • •