5,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The Mystery Press

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

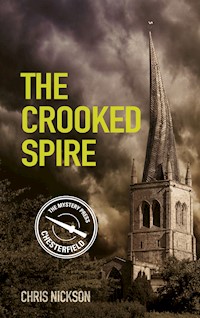

1361: Orphaned by the Black Death, all John possesses are the tools that belonged to his father, a carpenter, and an uncanny ability to work wood. His travels bring him to Chesterfield, where he finds work erecting the spire of the new church. But no sooner does he begin than the master carpenter is murdered and John himself becomes a suspect. To prove his innocence John must help the coroner in his search for the killer, a quest that brings him up against some powerful enemies in a town where he is still a stranger and friends are few. Chris Nickson brilliantly evokes the feeling of time and place in this story of corruption and murder.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

To Penny, because this is her favourite.

Contents

Title

Dedication

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-one

Chapter Twenty-two

Chapter Twenty-three

Chapter Twenty-four

About the Author

Copyright

CHAPTER ONE

Anno Domini 1360

He came over the rise, the bag of tools weighing heavily on his shoulder. The track snaked away in front of him, down the slope, with the soft promise of water at the bottom of the valley. Over in the woods a magpie chattered to its mate as it swooped through the branches.

The August sun was already fierce, even though midday was still four hours away. He shaded his eyes with a hand and squinted. In the distance he could make out the low roofs and the church tower of Chesterfield. Another hour and he would be there, with a dry throat and a hunger the size of England. The chantry priest in Dronfield had let him sleep on a bench the night before, but the man had possessed precious little food to share.

He strode out, stopping to drink at the stream and wet his head then cross himself for luck before striking out along the road into the town. There were few people about, but that was no surprise. Coming down from York he had often gone half a day or more without seeing a soul, his tongue and his heart aching for conversation and companionship.

When he was a child, before the great pestilence came and swept away most of the world, he felt he remembered people everywhere, a welter of conversation that filled his ears all day. He had helped his father then, beginning to learn how to make the wood do what he wanted, shaping and shaving it. But then his father was gone; his life withered to nothing in two brief days, and all John had left was the man’s satchel of tools and a mind that tumbled with memories and confusion.

He could recall the crops rotting in the fields at harvest time, not enough people still alive to bring them in, and the cows lowing until they died, their carcasses stinking and covered with flies.

He had taken to the roads that autumn, not wanting to cling to the few folk still alive in Leeds. He had the beginnings of a trade and it had served him well in the twelve years since. By God’s good grace he had a feel for wood. He could run his hands along the grain and understand how it should be, how to use its strength, where to cut and where to leave it.

A cart passed, going the other way, the horse plodding slowly between the traces, and he exchanged greetings with the driver, asking about the town ahead, eager for any gossip or information he could use. By the time they parted with a ‘God be with you’ he had learned there was work for a good man building the spire for the church, and the names of two places where he might find food and ale. Smiling, he walked on into Chesterfield, easing his way up the hill that climbed towards the church.

He glanced around with a curious eye, taking in the marketplace close to the building, then the construction of the spire itself. Groups of men were at work, the masons up high on the scaffold, laughing and joking as they laboured away, joiners busy under the shade of trees in the yard; it seemed a good site, with everyone busy enough.

He passed through, taking a turn around the town. Houses were packed tight along the streets and there was a sense of money about the place. Not wealthy, perhaps, but a comfortable little market town, and a growing one at that. The rich iron tang of blood hung in the air in the crowded streets of the Shambles, where the animal carcasses were suspended and goodwives haggled loudly with butchers over the price and quality of meat.

A few yards further, where the ginnel ended, stood another market place, the largest he had seen, bigger even than the one in York. Astonished, he stood and gazed over the space, imagining it full of traders.

He was still wide-eyed when a high voice close by said, ‘You need to see it tomorrow,’ and he turned quickly. The boy was no more than twelve or thirteen, not even any down on his chin yet, but he had a warm, guileless smile. His dark hair was awry around his face and he wore a cote of good cloth that was too short, as if the lad had grown too quickly.

‘The market’s Tuesdays by the church, Saturdays here. People come from all over for it. You’re new here, aren’t you?’

‘Aye,’ he agreed. The boy seemed harmless enough, but he still felt to make sure his purse was still attached to his belt. ‘It looks like a fair town.’

‘Wait until the morning,’ the lad inclined his head at the square, ‘you won’t believe it then. You’ve never seen so many people,’ he said, his eyes wide, then nodded at the man’s satchel. ‘What do you do?’

‘I’m a carpenter,’ the man replied. ‘I thought there might be work at the church.’

‘I’m sure there will be,’ the boy laughed. ‘They always seem to want people there.’

The answer didn’t surprise him. The death had carried off so many skilled men that a craftsman could earn good money these days, before he moved on when he wanted, safe in the knowledge that there would be work ahead of him.

‘I’ll go over there soon,’ he said.

‘I’m Walter,’ the lad told him and cocked his head questioningly. ‘What’s your name?’

‘I’m John.’

Walter smiled happily and nodded once more. He started to leave, but then looked back.

‘Do you need somewhere to stay John?’

‘I do,’ he replied. ‘Do you know of a place?’

‘Ask for Widow Martha on Knifesmithgate.’

‘Thank you, I’ll do that.’

And with that Walter waved and ran off, moving across the empty marketplace with the effortless grace of the young.

John tried to pat the worst of the dirt and dust from his cote and hose, then made his way back to the church. He watched the workmen for a minute before asking one of the masons for the master carpenter.

‘Over there,’ the man pointed, staring at the stranger with open curiosity while he drank from a mug. ‘They say he’s not easy to work for.’

John grinned.

‘I’ll survive; I’ve had hard masters before.’

The master carpenter was bent over, planing down a length of oak, sawdust and small curls of wood caught in the sweat and hairs of his broad forearms. He was stripped to shirt and hose, the skin on the back of his neck red and angry.

‘What do you need?’ he asked without glancing up.

‘I’m looking for work,’ John said.

‘You and a hundred others lad,’ the man answered.

‘I’m a carpenter.’

‘Oh aye? Where did you apprentice?’ He ran the plane along the beam again, then felt the surface delicately with his fingertips.

‘I started with my father in Leeds,’ John explained, ‘then the sickness took him. I’ve been on my own since then.’

The man stood up and faced him, assessing him coolly. He was small but with the breadth and thick strength gained from a lifetime of labour, his short hair heavily flecked with grey, his lips clamped in a thin line.

‘Let me see your hands.’

John held them out, palms upright to show the callouses of work.

‘Turn them over.’

He did as he was ordered, displaying the many small scars that stood out on his skin.

‘What’s your name?’ the man asked.

‘John.’

‘And where did you work last?’

‘York. At the Minster.’

‘Oh aye?’ The man said doubtfully and ran a hand across his chin. ‘No shortage of jobs up there for them as is willing.’

‘Could keep busy till Judgement Day, most likely,’ John agreed.

‘So why did you leave?’

He reddened. ‘A lass’s father thought I ought to marry her. We had words.’

‘Anyone hurt?’

‘No.’ He shook his head. ‘I left in the night on Lammas Eve. It was best to move on.’

The man nodded then inclined his head at the satchel.

‘Let me see your tools.’

John lifted the flap. The leather was old and scarred, and over the years he had mended the strap more times than he could count. But he had never been tempted to replace it. He remembered his father carrying it, the sound of it banging against his hip as he walked, looking down at his son and smiling.

‘Old but good,’ the master carpenter said. ‘Now let’s see what you can do with them.’ He gestured at a pile of offcuts thrown into a corner. ‘Make me a mortise and tenon.’

‘Can I have a drink first?’ John asked. ‘Been a long walk in the heat.’

The man chuckled. ‘Go on, then. The barrel’s there. I’ll come back in a few minutes.’

He slaked his burning thirst with two mugs of the small beer then set to work. He picked up a piece of the wood – good, well-seasoned oak – and caressed it tenderly, rubbing along the grain before setting it aside. Within a minute he’d selected the pieces he wanted, knowing they’d fit together well.

He worked quickly. The wood told you what it wanted, if a man knew how to listen. That was what his father had always said, and John had learned the lesson well. He made his marks carefully then worked with chisel and saw, each stroke deft and sure. He forgot all the sounds around him, absorbed in the task until it was done and he stood up, coming back to the world.

He watched as the man inspected the joint, easing it apart then pushing it back in place, checking how closely the two pieces fitted together before nodding.

‘It’s fourpence halfpenny a day and all your ale. A penny less in winter, if you last that long.’ He extended his hand and John took it, shaking it to give his agreement. ‘You can call me Will. But I’ll give you a piece of advice, lad.’

‘What’s that?’ John asked as he rubbed the tools with an oiled cloth before putting them away.

‘Keep your pizzle in your braies round here and don’t get any of the lasses with child. They have a temper on them, do Chesterfield men.’

John grinned. ‘I’ll remember that.’ He cast an eye over the building. ‘What church is this, anyway?’

‘St Mary’s, dedicated to Our Lady. Right, you start at daybreak and – ’ before he could say more there was a loud cry from the other side of the yard. Will ran towards the sounds, fast and agile.John slung his bag over his shoulder and followed, curious.

Two men were facing each other, one holding a knife, the other with a long cut along his forearm that dripped blood onto the grass. Will strode between them, pushing them both back. John came up quietly behind the man with the knife, clamping his hand around the man’s wrist, tightening his grip until the weapon fell from his hand. The man turned with pure fury in his dark eyes. He had thin, bony features; his lips were curled in a sneer, the heat of anger boiling off him.

‘Get him bandaged up and send him home for the day,’ Will ordered, as two of the workers led the injured man away. He turned to the one who’d wielded the knife. ‘And you, you’ve been nothing but trouble since I took you on.’

‘He went for me.’

‘I don’t give a rat’s arse what he did.’ Will stood close, his spittle landing on the man’s face as he spoke. ‘I’ll not have you here anymore. And you’ll not be paid for today.’ The man opened his mouth to speak but Will cut him off. ‘Get yourself away from here and you’d better just hope Stephen there doesn’t swear out a complaint against you.’

The man stood defiantly for a moment, then bent to retrieve his knife and walked away.

‘Is it often like that?’ John asked.

Will shook his head. ‘They’re good lads, for the most part. Loud when they’ve been paid, but that’s life. There’s always one, though. Anyway, start at daybreak, work until sunset. Be here in the morning and not a slug a bed like some of this lot.’

‘I will,’ John promised.

‘You did well there,’ Will added quietly. ‘Where did you learn that?’

John shrugged, ‘Around.’

CHAPTER TWO

All of Chesterfield knew Widow Martha, it seemed. The first man he asked readily gave him the direction to her house, taking time to praise her as a good Christian woman.

‘I’m told she takes in lodgers,’ John said.

‘One or two, maybe.’ The man looked him up and down, eyes taking in the plain russet cote, old hose, and dirty boots that had covered too many miles in recent days. ‘But she’s choosy.’

‘Well, happen she’ll choose me,’ John answered with a broad smile. ‘God be with you.’

The house on Knifesmithgate was the only one with its ground-floor shutters closed tight against the day. All along the street, cutlers had their wares on display, windows open to the day, the sound of grinding metal and voices spilling out into the light.

He knocked on the door, licking his fingertips and running them through his hair to try to tame it as he waited.

Widow Martha was a small, stooped woman, not even reaching to his shoulder. Her hair was hidden neatly under a crisp, clean wimple, a green wool dress over her round frame, and she was wearing a dark surcote in spite of the warmth. But it was her eyes that he really noticed, pale blue and calm, as clear and sparkling as any young girl.

‘Good day to you, Mistress,’ he said politely. ‘I am told you take lodgers.’

She gazed at closely him before she replied, ‘And who told you that?’ Her voice was light, teasing, a touch of music in her words.

‘A boy called Walter.’

Her glance moved to his satchel. ‘Are you working on the church?’ she asked.

‘I am, Mistress. Just arrived here and hired.’

‘How long do you intend on staying?’ A smile played across her lips. ‘I know you young men, you’re here one week, gone the next.’

‘As long as the work lasts,’ he told her, ‘and it seems like there’s plenty there yet.’

‘So they say,’ she agreed. ‘There’s still the spire to go on the tower.’ She paused. ‘What’s your name?’

‘John, Mistress.’

She nodded. ‘And do you keep the gospels, John?’

‘Not always,’ he admitted wryly, although she had likely guessed it already.

She stepped aside, holding the door wide. ‘Come in,’ she said, ‘you’re welcome enough. There’s a place for you here, if it suits you. Call me Martha.’

He stepped through an empty workshop, to a small, neatly kept hall with two benches against the walls, and a well-polished table and small joint stool in the middle of a floor covered in fresh rushes and lavender. A rough wooden staircase led up to the solar. The back door stood open, trying to draw in a cool breeze, looking out on the long burgage plot of the garden, heavy with vegetables.

‘How do you know Walter?’ Martha asked, sitting calmly on the settle.

‘I met him near the marketplace,’ he told her, nodding his approval at the house. ‘Are there really enough traders to fill all that space?’

‘You should go down one Saturday and see for yourself,’ she told him with a smile. ‘Walter must like you. He wouldn’t have recommended you here if he didn’t think you were trustworthy.’

‘He’d barely met me two minutes before,’ John protested.

‘Don’t you underestimate that boy,’ she chided gently. ‘He might have young shoulders, but there’s a wise head on top of them and a good heart inside. He does jobs for me when I need them. He only lives round the corner with his mother and his sisters.’

‘What do you charge for lodging, Mistress?’

‘It’s threepence for a week, tuppence more if you want your food too. I keep the sheets clean and changed regularly. The food’s filling, even for a working man.’

‘I’ll stay,’ he said, digging in his purse for five small silver coins.

‘It’s a good house, if I say so myself,’ Martha said, closing a small fist around the money. ‘I’ve been here nigh on thirty years now. My husband was a cutler – God rest his soul – and I couldn’t bear to leave after he died.’

• • •

The room was small, tucked away at the back of the house, with an unglazed window looking over the garden and out across the long valley to the north. He sat on the bed, feeling the firm straw and the sheet crisp against his touch. A small chest stood open against the wall; he placed the satchel carefully inside it before using a small cake of lye soap to wash his hands, face and feet in a ewer, enjoying the delicious coolness of the water then drying himself on the scrap of old linen Martha had given him. There was ample daylight left, time enough to go and explore Chesterfield properly. Instead he stretched out, hands behind his head, and let sleep carry him away.

• • •

The morning was a thin, pale band on the horizon when he woke. He pulled on his boots, picked up the tools and tried to move quietly through the house. But Martha was already there by the front door, fully dressed, her face half-lit by the flame of a tallow candle.

‘Here,’ she said, passing him a small package wrapped in old fabric. ‘You had no supper, so there’s something for your dinner.’

‘Thank you, Mistress,’ he answered in surprise. ‘That’s a kindness.’

‘Oh, get on with you,’ she told him kindly. ‘And I told you to call me Martha. Everyone else does. There’s a market today, just tell me if you want me to buy you anything.’

‘Bread and cheese, if you would.’ He began to open his purse but she just shook her head. ‘Pay me tonight.’

As he walked down the street he could hear people moving around behind their doors, the day already beginning. Over in the churchyard small groups of men stood together, some going over to the barrel to fill their mugs with ale.

He looked around in the gloom, finally spotting Will by the church, staring up at the tower.

‘Good morning, Master,’ he said. ‘What do you want me doing today?’

‘There’s work up there,’ Will told him. ‘We need to finish reinforcing the ceiling in the top room. Next week we start work on the spire.’ John followed his gaze, trying to picture it. Already it seemed tall enough. ‘It’ll be more than two hundred feet high when we’ve finished. People will see it for miles around.’

‘What’s going to hold it in place?’ He couldn’t even start to imagine what would be needed to keep a structure like that sturdy.

Will grinned broadly. ‘That’s the beauty of it, lad. It’ll be heavy enough that its own weight will keep it there.’

‘What?’ John looked up again. It seemed impossible. Any strong wind would topple it if it wasn’t attached. But if it worked, if it could stay, it would be one of the wonders of the world.

‘That’s what the engineers tell me, any road.’ He scratched at the dark stubble on his chin. ‘And they’re the ones who are paid to know. So that’s why we need the ceiling strong. Good cross-bracing.’

The dawn had lightened enough for John to make out Will’s features and see the glimmer of doubt that flickered across his mouth and troubled his eyes. If anything went wrong it would be the master carpenter and his men who would take the blame first. Will drained the mug in his hand.

‘Right,’ he said, ‘off you go. One of the engineers will tell you what to do. Can you read a plan?’ John shook his head. ‘Then just do exactly what he tells you. There’ll be some others up there. I’ll come by later and see if you’re as good as you think you are.’ He gave a wink and strode away.

John entered through the porch and made the sign of the cross. The stairs were close to the screen, and he stopped for a moment to look around. It didn’t compare to the great Minster in York, but nothing could; that was a building as large as any castle. This church had a pleasing symmetry in its shape, though, and he ran his hand along one of the decorated pillars, feeling the sharpness of the mason’s cut in the stone before climbing the winding staircase.

The room stood open to the sky, tall enough to catch the faint morning breeze. Already there was the scent of heat in the air, and he knew that in another hour he’d be covered in sweat and stripped to his shirt. He put the satchel carefully in a corner and examined the area. Some beams were already in place, a basic structure that was solid when he pushed against it.

He heard footsteps and turned. A man in a cote of expensive wool topped with a dark blue surcote entered, followed by three others. He carried a piece of vellum rolled in his fist, while one man carried a bag, the others were empty handed. They were big men with thick hands and muscled arms.

‘You’re the new carpenter?’ the man asked without any real interest. He was short, with a hawk nose and weary eyes, carrying his air of self-importance like a crown as he unrolled the plan. His fingernails were clean, his hands as smooth as if he had never used them more than was needful.

‘I am.’

‘Have you done any cross-bracing before?’

‘Aye, some,’ John said. He’d done most everything in his two years in York, but he listened closely as the man explained everything in his haughty voice, his mind’s eye seeing each piece go into its place to ease the weight and spread the stress of the spire.

He set to work with the other carpenter, a thin, dour man named Robert who spoke little, and with hair the colour of iron cropped close against his skull. The labourers did the hardest work, shifting the heavy beams and helping to keep them steady.

By the time the bell sounded for dinner the linen of his shirt was soaked through. The sun burned down hot, not a cloud in the sky, the room trapping the warmth like an oven.

Outside, he found a place in the cool shade of a birch tree and took a long draught of ale and began to eat. He had almost finished when Will came by. John had watched him going around his men, talking to them, asking interested questions. A good master, he decided, one who cared about the job and those under him.

‘How are you getting on up there?’ he asked.

‘Slow but steady. It’ll take a few days to have everything secure.’

‘There’s time yet. Just make sure it’s right. What do you think of the engineer?’ John turned his head and spat. Will roared with laughter. ‘Aye, he’s an arrogant streak of piss, but he knows what he’s doing. That’s more than you can say for some of them.’

John nodded and watched idly as Will passed a moment with a group of men. He stood and stretched before returning to the room at the top of the tower.

They worked hard all day, never as fast as the engineer wanted, but John didn’t care about that. If he was going to do a job he had do it properly and at his own speed. He had pride in what he did; no one would ever need to go over it.

He finished as the shadows fell and it became too difficult to see. Carefully, he wiped the tools with the oiled cloth, slung the bag over his shoulder and walked down the stairs, the leather rubbing noisily against the stone as he moved. His arms ached, but that was a good feeling. Along with the others he lined up to be paid, making a mark with a quill before slipping the coins into his purse.

The dying of the day had always been his favourite time, the sounds muted, the night scents appearing on the air, a suspicion of magic in the sky. He leaned against the wall of the churchyard, looking down the slope towards the river that moved sluggishly in the distance and felt the satisfied weariness of labour done well. A man was his work, and the ache in his muscles felt as rich as any full coffer.

It was full dark when he returned to the house on Knifesmithgate, opening the latch quietly in case Martha was already asleep. But a rushlight burned bright and she was seated on the bench, her back straight, eyes bright and alert. She had a needle and thread in her hand and a small pile of sewing at her side.

‘Good evening, Mistress,’ he said, then corrected himself with a smile as she gazed steadily at him. ‘Martha.’

‘There’s ale on the table for you,’ she told him, ‘and a coney for dinner tomorrow, if you’ve a mind.’

‘I’d like that. Thank you.’ He drank and settled himself on the joint stool. ‘I’m surprised you don’t have a servant here. I thought all women did.’

She chuckled and shook her head. ‘Shows how much you know. Most of the ones I’ve had couldn’t do anything right, I always ended up doing it myself anyway.’ She caught his grin. ‘Besides, if I had a servant, what would I do all day? You men have your work, but what do I have?’

‘You don’t have any children close by?’

‘There’s only one still alive,’ Martha said with a gentle sigh, ‘and she’s up in Sheffield with a brood of her own. Married to a cutler, of course, and he’s doing well in his guild. They come twice a year to see me.’ She paused, as if she was embarrassed to tell him so much. ‘I left the bread and cheese in your room.’

‘Thank you.’

• • •

The next morning was Sunday, and John escorted Martha to the church as the bell rang, leaving her to stand at the side along with the widows and crones, where they could exchange gossip behind their hands. He took his place at the back among the workmen, nodding a greeting to the few faces he recognised.

Close to the front he spotted the lad Walter, there between women he assumed were his mother and sisters. The boy smiled to see him and leaned over to whisper to one of the girls. She turned to look, a promise of mischief and flirtation in her eyes and a bold smile on her bonny face.

He hurried away after the service, glad of his own company to wander around Chesterfield on the quiet streets, taking a path down to the marshy area around the river and staring back up to see the church tower standing proud and tall. What would it be like with the spire on top of that, he wondered.

He made sure he was back at the house on Knifesmithgate for his dinner, an edge to his hunger, ready for the tender rabbit that Martha had cooked in a heady pepper sauce with other spices he couldn’t name. He ate slowly, relishing each mouthful, spearing the food with his knife and chewing slowly, trying to remember when he had last had a good meal in someone’s home. For so much of his life his food had come from cookshops or charity as he walked between towns.

In the afternoon he did some small jobs for the widow, adding a thin shim to a joint in the settle to stop it wobbling, then planing down the bottom of the back door where it stuck on the stone of the step. It took no more than a quarter hour and it was repaymeny for the woman who had just fed him so well.

• • •

He entered the churchyard in the half light, pausing for a quick drink of ale from the barrel before climbing the stairs to the tower. The stars stood bright, clear in the still sky. He had heard once how some men claimed to understand them and what they meant, but he knew nothing of that and never would.

He started to ease the bag from his shoulder then halted as he breathed in. The room stank of decay. He coughed, tasting the bile as it rose in his throat, then put a hand over his mouth.

In a few moments he could make out enough to see the shape on the floor. It was large enough to be a man – a corpse. He took the steps at a run, gasping for clean air, and rushed out of the church.

‘In the tower, quick!’ he shouted. ‘Someone’s dead up there.’

CHAPTER THREE

Men dashed from across the churchyard, pressing into the building and up the stairs to the tower. John stayed outside, leaning against the stone, breathing in the clean air deeply and letting the sweat of fear cool on his skin. He had seen too many bodies before, many of them with the agony of the plague on their faces; he had no wish to see another.

He could hear the hubbub of voices, then the sharp, distinctive sound of someone striking a flint to light a candle.

‘Christ’s blood, it’s Will,’ a voice said, the words carrying in the dawn. ‘The crows have been at him, too. Go for the coroner.’

John slid down the wall, resting on his haunches and sighing. With the coroner coming and the inquest in the tower there’d be no work done today. And as first finder he would have to give his evidence then pay a fine to make sure he stayed in the district.

It was full morning before the coroner finally appeared, a tall man with thick, pale hair, wearing polished boots, red hose and a blue cote buttoned up tight, a monk for his clerk limping behind him and carrying a small, portable desk.

The man must have selected his jury on the way. Six men trailed along, some looking around curiously, others try to hold back, reluctant to be there but knowing they couldn’t refuse.

‘Where’s the body?’ the coroner asked.

‘Top o’ there,’ someone told him, pointing to the tower.

‘Who’s the first finder?’

John stood slowly.

‘I am,’ he said.

‘You come too, then,’ and motioned for the jury to follow him.

The room seemed cramped and airless, the stench more powerful than before. Men were packed together in the space, gagging and retching; two went to the corner and vomited. John stayed back, hating all this but unable to keep his eyes from the body.

It was Will, no doubt about that. Enough remained of his face to be sure of that; the birds and rats had taken the rest and now flies were thick on his skin. He lay crumpled in the middle of the floor, so much smaller in death than he had seemed in life. A lake of blood had bloomed under him, dried now to a thick, dark stain on the wooden boards.

The coroner turned Will over gently with his boot, an expression of distaste on his mouth. Maggots crawled around the deep wound on his back; the shirt soaked a deep red.

‘I’ll hold the inquest in the nave,’ the coroner announced, then turned to the monk. ‘Arrange for some of the women to prepare him for burial.’

The jury assembled near the font, the clerk sitting with the desk on his lap, quill ready.

‘Who was he?’ the coroner asked.

‘His name was Will,’ John said. ‘He was the master carpenter.’

‘English?’

‘As much as you and me, aye.’

‘You found him?’

‘I did,’ he answered with a brisk nod.

‘And who are you?’ the man wondered. ‘You’re not from here.’

‘I’m John. Will hired me on Friday. I’m staying with Widow Martha on Knifesmithgate.’

He felt the coroner’s pale eyes on him.

‘What were you doing in the tower?’

‘Getting ready for work. We’re putting cross-bracing in there for the spire.’

‘Who told you to go up there?’

‘No one.’ John took a breath. ‘I’d been working up there on Saturday and there was still plenty to do.’

‘What did you do when you found him?’

‘I came down to raise the alarm.’ The memory came back to his throat and he swallowed. ‘I could smell him, but it was too dark to see who it was.’

‘When did you see this Will last?’

‘Saturday evening, when he paid the men. All the men,’ he added.

The coroner turned to the clerk.

‘Fine him a shilling as first finder.’

Head bent, the monk nodded.

‘What do you think, jury?’ the coroner asked.

‘Someone killed him,’ a man at the front said. ‘Knifed him in the back. It’s obvious to anyone.’ He turned to glance at John. ‘Could have been him for all we know.’

‘Anyone else?’

‘He’s been there a while,’ an older man added thoughtfully. ‘A man don’t end up like that in an hour, stinking and pecked to buggery.’

The coroner nodded.

‘I pronounce Will unlawfully murdered.’ He looked around the men. ‘I charge the jury with finding his killer.’ Finally he turned to the clerk again. ‘Take their names before you let them go.’ Then he strode off, gesturing to John to follow him.

They stood in the porch, looking out at the groups of men gathered in the yard.

‘How well did you know him?’

‘Not at all,’ John answered.

‘Do you know of anyone who’d want to kill him?’ the coroner persisted.

He thought back to Friday and the fight Will had broken up.

‘I saw him dismiss a man just after he had hired me.’

‘What happened?’ The coroner stared at him curiously, his pale eyes intent.

‘A couple of the workers were fighting. One of them cut another.’ He shrugged. ‘From what I heard, the man with the knife had been a troublemaker and Will sent him on his way without his wages.’

‘Was it reported?’

‘I don’t know,’ John told him, seeing the doubt on the other man’s face.

‘Do you know the man’s name?’

John shook his head. ‘Stephen, I think. He was the one who was hurt.’

‘Where is he?’

John inclined his head. ‘He’ll probably be out there somewhere. Look for someone with a bandage on his arm. He can tell you more.’

‘You’re not a helpful man,’ the coroner said, his voice bemused. ‘Didn’t you like Will?’

John was slow to reply. ‘He seemed liked a good master, he looked like he cared about the people working for him. But like I said, I didn’t know him.’

‘Go and pay your fine. You’re a stranger here; that makes you a suspect in the death.’

He had known those words would come. No one knew him here; there wasn’t a soul to speak for his good character.

‘Most of the people working on the church aren’t local,’ he countered.

‘They didn’t find him,’ the coroner said firmly. ‘You did.’ He turned and strode away, out of the churchyard.

John sighed. He leaned against the wall, waiting until the jurors had filed out, their faces set, two of them glancing angrily at him as if they blamed him for their task. Then he returned to the nave, the flagstones solid under the sole of his boots, to the clerk slowly packing away his vellum and ink.

‘My fine,’ he said, counting out coins from his purse and passing them over. He hated to lose the money, but knew he had no choice. He was better off than many; he had worked steadily for a long time and spent little of his wages. Most of his small wealth he had painstakingly sewn away in his cote, safe from the eyes of thieves and cutpurses.

The monk took the money with a nod, sliding it into the scrip that hung from his belt. He had a long face with all the lines of age but a lively mouth that twitched into a smile.

‘Don’t worry,’ he said, ‘he doesn’t think you did it.’

John raised his eyebrows. ‘How do you know?’

‘If he’d had any doubts about you he’d have arrested you straight away. I’ve seen him do it before.’ The man stood, smoothing down the black habit that had been patched and mended many times. A shaft of sunlight through the window of the church shone on his tonsure.

‘How long have you clerked for him?’

‘Five years come Michaelmas. He’s a good man, is Richard de Harville.’ He picked up the small desk wearily and put it under his arm. ‘He’s thorough in his duties.’

‘You need a strap on that,’ John told him. ‘That way you could carry it on your shoulder. Find some leather and I’ll put one on for you.’

‘That would be a kindness,’ the monk said, inclining his head. ‘I’ll do that.’

‘How does a Benedictine come to work as a clerk?’

‘There’s a tale in that, right enough,’ the man said with a grin. ‘I taught Richard his letters when he was little, before he inherited the manors from his father. When the king appointed him coroner around here, he asked the abbot for my services. So I was called to God but I end up serving man once more,’ he finished with a sigh.

‘And do you like living back in the world?’

‘Not so much, to tell you the truth.’ He walked towards the porch with the slow gait of an old man who had traipsed too many miles. ‘The monastic life chose me, I was happy in it. I’ve asked to go back, but the Master says he needs me.’ At the porch he straightened a little. ‘God go with you, John Carpenter,’ he said.

• • •

The men clamoured around, eager for the gossip and the verdict. John told them briefly, his eyes moving around, searching for someone. Finally he saw Stephen, standing by the barrel of ale, a dirty bandage wrapped around his forearm.

Soon enough the questions faded, men wandering off to spread the word of Will’s murder. John strolled across and poured himself a drink.

‘How’s the arm?’ he asked.

‘Well enough,’ Stephen answered with a small shrug. He was tall, with a thick growth of beard on his sallow face and his hood pulled back to show long, stringy hair. ‘I can still work, if there’s anything for us today.’

‘There won’t be,’ John told him. ‘Not with Will dead.’

‘You’re the one who found him?’

‘Aye.’ He took another drink, trying to wash the taste of death from his mouth.

‘How did he die?’

‘Knifed, by the look of it.’ He let the words sink in for a moment. ‘That one who attacked you, who was he?’

‘Mark?’ Stephen shook his head. ‘He was just one of the labourers. Turned up drunk most days, when he showed up at all. Always with a temper on him too, just itching to pick a fight.’

John knew the type all too well; there were one or two like that on every site, never happy, never satisfied, their anger lying too close to the surface.

‘What happened on Friday?’ he asked.

‘He tried to push in front of me for the ale. I wasn’t having that. He pulled out the knife and cut me.’ His voice turned boastful. ‘Another minute or two and I’d have put that blade up his arse.’

‘This Mark, is he local?’

Stephen shrugged. ‘I never asked.’

John put down his empty mug. ‘God be with you. Maybe we’ll all be able to earn some money soon.’

He was scarcely ten yards down Knifesmithgate before Walter was at his side, all gawky limbs and questions.

‘Did you really find him?’ he asked, walking quickly to keep pace.

‘Word travels fast here,’ John replied, smiling inwardly at the boy’s eagerness. ‘But I did.’

‘What was he like?’

He stopped, put a hand gently on Walter’s shoulder. ‘He was dead, lad. That’s all you need to know. It’s not a sight anyone wants to recall, believe me.’

The boy’s face fell for a moment, but then brightened again. ‘Do they know who did it?’

‘Not yet.’ He smiled sadly. ‘The coroner thought it might be me. I found him, and I’m a stranger.’

‘You?’ Walter looked shocked. ‘You’d never hurt anyone like that.’

‘No,’ he agreed. ‘But don’t be so trusting. You don’t know me.’

‘But I can tell,’ the boy protested.