Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Books on Demand

- Kategorie: Wissenschaft und neue Technologien

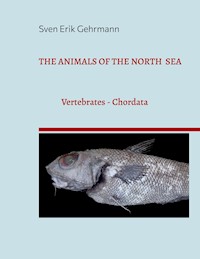

- Serie: The Animals Of The North Sea

- Sprache: Englisch

Part I of this book series puts vertebrates (Chordata) of the North Sea, from sea-squirts to lampreys, sharks and rays, bony fishes, seals and whales, in the context of the changing living conditions in this small part of the one big ocean. The book presents a balance between long-established species and immigrants from the subtropics. Aspects of fishing, ecology and aquarium keeping were also included in this work. In addition, the preparation of fish was also addressed. It would be very welcome, if in the future more people would concern themselves with the care and preservation of the wondrous and multifarious inhabitants of the North Sea. For unfortunately, many of the species shown here seem to be largely unknown to a wider public, which is why they hardly seem to have a real lobby in practice. So, we`d better get to know our endemic species, before they become extinct.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 384

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

CONTENT

Introduction to a complex topic

Prologue

Habitats of the North Sea Animals

The Living Waddens

Algae/Seagrass Zone

High Seas

Cultivators and Neozoans in the Harbour Habitat

Block and Boulder Bottom

Wrecks

The Inhabitants of Sandy Bottoms

Heligoland & Rocky Coasts

Mussel Beds

Restless Wanderers between different Waters

Stray Visitors of the North Sea and the Baltic Sea

Temporary Sandbank Habitat

Finally, a new Habitat: The Rubbish Bank...

ANIMALS OF THE NORTH SEA – Vertebrates -

Chordata

Subphylum

Tunicata

- Ascidians

Class

Ascidiacea

– Sea-Squirts

Class

Appendicularia

– Tailed Sea-Squirts

Superclass

Agnatha

– Jawless

Part Tribe

Chondrichthyes

- Cartilaginous Fishes

Class

Elasmobranchii

– Fish with Plate Gills

Gigaclass

Actinopterygii

– Ray-Finned Fishes

Preparation of Fish

Invertebrate Parasites of Fishes

Sturgeons -

Acipenseridae

Garfish -

Belonidae

Rockskippers or Combtooth Blennies–

Blenniidae

Garden or Conger Eels –

Congridae

Freshwater Eels –

Anguillidae

Shads, Sardines, Menhadens or Herrings -

Clupeidae

Anchovies –

Engraulidae

Silversides –

Atherinidae

Salmonids -

Salmonidae

Smelts -

Osmeridae

Cods and Haddocks-

Gadidae

Hakes and Burbots –

Lotidae

Merluccid Hakes –

Merlucciidae

Ocean Sunfishes or Molas –

Molidae

Mullets –

Mugilidae

Temperate Basses -

Moronidae

Sticklebacks -

Gasterosteidae

Seahorses and Pipefishes -

Syngnathidae

Scorpionfishes -

Scorpaenidae

Gurnards –

Triglidae

Lumpfishes and Snailfishes–

Cyclopteridae

and

Liparidae

Remoras –

Echeneidae

Scaleless Sculpins or Bullheads –

Cottidae

Sea-Poachers, Bandidos or Alligatorfishes –

Agonidae

Goatfishes –

Mullidae

Jacks and Pompanos –

Carangidae

Porgies or Picarels -

Sparidae

True Perches –

Percidae

Weeverfishes -

Trachinidae

Bonitos, Mackerels and Tunas -

Scombridae

Wrasses –

Labridae

Eelpouts –

Zoarcidae

Shannies or Pricklebacks –

Stichaeidae

Gunnels -

Pholidae

Wolffishes -

Anarhichadidae

Sand Lances or Sandeels -

Ammodytidae

Gobies –

Gobiidae

Dragonets –

Callionymidae

Swordfishes –

Xiphiidae

Righteye Flounders –

Pleuronectidae

Lefteye Flounders -

Bothidae

Turbots -

Scophthalmidae

Soles -

Soleidae

Boarfishes -

Caproidae

Dories –

Zeidae

Deep-Sea Fishes

Marine Hatchetfishes –

Sternoptychidae

Subfamily

Sternoptychinae

, True Hatchetfishes

Goosefishes -

Lophiidae

Cutlassfishes -

Trichiuridae

Rattails or Grenadiers –

Macrouridae

Tribe

Mammalia

- Marine Mammals

Atlantic Harbour Seal,

Phoca vitulina

Sea-Pig or Common Porpoise,

Phocoena phocoena

Sperm Whale,

Physeter catodon

An open Letter to the Japanese Embassy in Berlin:

Recommended Facilities on the Topics of North Sea Animals and Fisheries

Thanx, Copyright & Pictures

Literature and Sources

Epilogue, Springtime 2016 - Springtime 2023

Latin Nomenclature Register

About the Author

The Tompot Blenny Parablennius gattorugine now occurs even in the German Bight…

What kind of future will species like the common haddock (Melanogrammus aeglefinus) once have in the North Sea, if the climate change brings a warming up of the sea-water?

Prologue

1983, Island Borkum: I, then 14 years old, got the chance of a lifetime: I was allowed to go out with a real professional fisherman. To catch true shrimps! I remember how we lowered the net off the Bird Island Rottum in July 1983 at clear sight. Two mighty beam trawls dragged evenly along the bottom on each side of the boat. After an agonising three quarters of an hour, the mighty beam trawls were then hauled in by means of a winch. Full of joyful anticipation, I hopped across the deck and - much to the anguish of the fisherman - almost got the beam trawls on my head with excitement. The net was full of true-shrimps, in Germany also known as "crabs". Large pipefish and red gurnards particularly fascinated me. We also caught loads of flatfish of all sizes, various yellow eels and soles. The latter two of which we pan-fried fresh on board. I had never fish! And today?

2003, Island Baltrum: A short holiday with the family. Lately, giant Pacific oysters (Magallana gigas) have been appearing in the mudflats; sporadically on stones. It's April, the sun shines so often, that the islanders have to turn on their sprinklers, because the grass on the island is beginning to wilt. I also find swimming crabs of the species Portumnus latipes, which is distributed as far as North-West Africa, washed up on the beach. All females, which came to the warmer North Sea to reproduce...

2011, Norddeich: In the harbour basin small fish swim on the surface, 2 centimetres. An examination reveals that they are juvenile sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax). In the mudflats of Norddeich, not a single flatfish can be caught with a landing net... The harbour pier is overgrown with Pacific oysters.

2012, Island Baltrum: It is high summer in August. Anglers stand on the groynes at high tide. What do they catch here? Sea bass; the island record is 70 centimetres long...

2012, Norddeich: No sea bass in the harbour basin this time, but small flatfish on the mudflats... At least, but only a few. A result of the cold winter?

2013, Norddeich: With the bait sink, some eelpouts (Zoarces viviparus) can be detected in the harbour basin. But also an introduced shrimp from Korea, Palaemon macrodactylus.

2014, Norddeich: And again the shrimp-trawlers brings egg-bearing females of the subtropical swimming crab Liocarcinus navigator in April. The water is too warm for the season. Summer started…

Spring 2015 and 2016, Norddeich: The trawlers catch dogfish, blonde rays, anchovies... All immigrants from the English Channel. The winter of 2014/2015 was once again far too warm for our latitudes...

2017, muddy weather in East Frisia: No real summer, it is constantly humid or rainy, the farmers have many problems to be able to harvest anything at all... The by-catches of the fishermen turn out very differently, certain otherwise common species are rare...

2018, Norddeich: Heat wave! Many otherwise common fish species were hardly caught by the fishermen in summer. Because with a surface temperature of 22° Celsius in the southern North Sea, they prefer to stay in deeper areas, where no one fishes... In the Baltic Sea: 25° Celsius and vibrion alert! In addition, one could observe considerably more jellyfish than usual... Have they decimated the fish fry?

2019, Norddeich: Catches of the bluemouth rockfish Helicolenus dactylopterus in the flat Wadden sea prove, that deep-water dwellers from the English Channel now migrate to the northern areas of the North Sea. Catches of juvenile devilfish (Lophius piscatorius) sustain this thesis.

July 2022, Island Norderney: The subtropical horse mackerel (Trachurus trachurus) has successfully reproduced here off the East Frisian Islands. I could catch the juveniles in the harbour!

February 2023, Norden: Subtropical horse mackerels and red gurnards were caught by our local fisheries… Subtropical species in the winter! Quo Vadis, North Sea? Everything`s got a mess here!

Habitats of the North Sea Animals:

To gain a deep and true understanding of the animals of the North Sea, one should first look at the habitats where they regularly occur and can be found. Therefore, the next few pages briefly portray some of the habitats of the North Sea to give you an idea of the circumstances and natural forces that affect the organisms. Then you also begin to understand, why certain creatures only occur in certain places and not at all in others, or only in exceptional cases. Adaptations to environmental conditions and enemies also become clear. In the overall ecological structure of the North Sea, fish take on very different roles. Many species of fish are an important source of protein-rich food for birds, other fish, marine mammals and humans. And without them some natural phenomena could not take place properly, such as the annual migration of birds. In particular, the fish species found in the tidal flats also tolerate low and fluctuating salinity and temperatures. Unfortunately, most of the North Sea's habitats are threatened by the numerous influences of humans, and at the present time no all-clear can be given here. Business groups want to drill for oil in the middle of the national park, chemical companies dump thin acids, sometimes illegally, or burn highly toxic chemical waste at sea. And the railing is still the sailor's favourite rubbish bin. Official estimates suggest, that there is about one tonne of visible human waste per square kilometre of tidal flat. On an internal paper, the government of the Federal Republic of Germany admitted in spring 2010, that the protection of the North Sea has obviously failed, as shipping in particular does not comply with existing environmental laws... The waste often has devastating consequences for the inhabitants of the sea. For it often cannot be degraded quickly and makes entire regions uninhabitable due to the subsequent contamination. In addition, there are dumped munitions from First and Second World War, as well as rapid climate warming up, which can have dramatic effects on some marine organisms. The Biological Institute on Heligoland, for example, has documented a warming of the North Sea water by at least 2° Celsius since it began keeping records more than a hundred years ago. These are facts, to which one can no longer close one's eyes. Therefore, climate protection should be made agenda item No. 1 of all political efforts. The years from 2018 to 2022 seem to be the warmest years since weather records began. It is really quite astonishing, that the energy companies still want to fuel the world's climate by burning lignite and seem to have little interest in expanding renewable forms of energy. And that our state refuses to fight the general waste of electricity on a broad scale. (Just Corona-crisis and Ukraine-war started to change that a little bit). Many things could be implemented quickly in the short term - just think of switching off superfluous neon signs in the large conurbations, to name one example. Or stopping inland-flights. And politicians could also do a lot more to stem the tide of plastic. Why, for example, do televisions have to be packed in polystyrene and plastic film? Couldn't we just use cardboard or wood wool? It is simply appalling, how much has not been done here in recent years. Appalling for a widely disappearing marine fauna, of which most people in Europe are obviously neither present nor aware. This work is intended to contribute to remedying this state of affairs. If you are on holiday at North- or Baltic Sea, you too can make a small contribution, for example by collecting and disposing of any rubbish you find. Many people, big effect!

The Inhabitants of Muddy Sea-Bottoms

We are far below the tide mark at a depth of at least 20 metres. Here, fine sediments and remains of dead marine life are deposited, forming a thick bank of mud. At first glance, you cannot spot the inhabitants of this mud desert, but with a bit of luck you can see their traces: Crawl marks of molluscs and echinoderms, burrow marks of worms and crabs and small footprints of all kinds of crustaceans that have traipsed along here. Here and there you can also see the odd hole inhabited by organisms as diverse as Norway lobster and cylinder anemone. The "mud desert" is alive in many different ways! If we were to deposit a bait, such as a dead fish, on this surface, we would shortly be able to locate the approach of various inhabitants of the muddy bottom. The smells of the bait would soon attract various worms, carnivorous snails, brittle stars, predatory starfish and crabs. But one or two sea anemones would also suddenly emerge from the bottom to get a piece of the prey as well. Most inhabitants of the muddy bottom keep themselves hidden. Either to escape their enemies, or to lurk for prey themselves. And some form alliances of protection and defence, such as the Norway lobster with the Fries` sea goby. The few inhabitants of the mud bottom that can afford an exposed position above the ground are either inedible to most predators, such as the sea pen, or they have effective stinging poisons, such as the cylinder-anemone. Still others, such as certain fish, hover close to the bottom and lie in wait for unwary prey. Unfortunately, beam trawls are also often used here to fish for species such as flatfish or Norway-lobsters. This causes massive disturbances on the seabed. In some areas, for example, entire populations of sea feathers have "disappeared", so that these actually common organisms are now in retreat. All this has consequences, which are not always immediately visible. But when cod and herring are suddenly "gone", yes, then the fisherman complains!

The Living Waddens

A stranded jelly fish has fallen dry during the low tide.

Bladder Wrack (Fucus vesiculosus). Amphipods and shore crabs are often found in such algae, but also plastic waste, nylon threads and, as here, the feathers of seabirds.

Even the muddiest mudflats are home to a wide variety of life - from small snails to lugworms, mud crabs, various mussels, crustaceans, shrimps and juvenile fish. This extreme habitat is subject to some strong fluctuations: Low tide and high tide alternate twice a day to create dryness and current, and due to certain sun-, moon-, and wind constellations there can be both very low tides (neap tide) or very high water levels (spring tide). Furthermore the seasons provide a wide range of temperatures, with extremes ranging from ice floes in winter to very high heat in the tidal pools in summer, where the sun can heat water temperatures to more than 30° Celsius. Heavy rainfall can cause significant fluctuations in salinity in the tidal flats and ebb pools. The wind can drift considerable amounts of sand in a very short time, so that new sandbanks and islands are constantly being created, and others sink into the sea. There is high enemy pressure and a high density of individuals of a wide variety of species. The plant food basis for the abundance of shrimps, fish and other small animals is provided by tiny diatoms, which use the tidal flats as a gigantic production field. These also cause the mudflats to look somewhat brownish most of the time. The mudflat bottom consists of 3 different layers: The uppermost layer down to a depth of about 5 cm can be described as an oxic stratum, in which there is a relatively high oxygen content, so that quantitatively most animals are found on or in this layer. This is followed by a suboxic layer, which runs from about 5cm - 15cm depth. In this layer there are still some worms and mussels that can manage with less oxygen, or that are able to get the oxygen they need from above through long connecting passages to the surface or through long siphons. Underneath then runs an anoxic layer, usually blue-black in colour, in which numerous anaerobic bacteria live, which utilise the metabolic waste products of other organisms. This layer in particular ultimately acts like a gigantic natural sewage treatment plant. Since the mudflats are biologically highly productive and produce a lot of biomasses, they are also frequented by numerous seabirds and migratory birds, which find an abundantly laid table here. The mudflats can be very different in nature, as there are mudflats, mixed mudflats and several intermediate forms. Depending on the substrate, the mudflats are also populated by very different animals and plants. Mud crabs and worms in particular play an important role here, because they clean the mudflats of all kinds of organic waste and ensure a fluctuating exchange of nutrients through all the layers of the mudflats. Mussels also make an important contribution to this, but as shellfish they do even more. This is because their empty shells are finely ground by the current and thus shape the consistency of the tidal flat quite considerably. Where there are large mussel beds and stocks, the tidal flats are also much less muddy. And thus much easier for people to walk on! Finally, a request to nature lovers: If you find small pieces of plastic waste during a mudflat hike, please take them with you. Because even the finely rubbed microscopic plastic waste has long since become part of the tidal flats and thus enters the marine food web...

Algae/Seagrass Zone

Seaweed and seagrass zone with the sea lettuce Ulva lactuca.

The small seagrass Zostera nana disappeared extensively from the tidal flats of the German Bight in the 1930s because of introduced pathogens...

This habitat overlaps with the mudflats and differs from the mudflats overgrown with diatom turf in that here one can find densifying stands of higher seaweed and seagrass. Depending on the season, the mudflats can become an algae zone and vice versa. Thus, this section can also be considered a temporary habitat. Humans exert a direct influence on the emergence of algal assemblages here through the discharge of phosphates and other fertilisers into the sea. In particular, fast-growing algae such as the sea lettuce Ulva lactuca are subject to this influence. In shallow water, algae provide cover for numerous animals against the many feathered aerial predators, but they serve as food for only very few species of fish in the North Sea. A wide variety of animals can be found here, depending on the season: In spring and summer, for example, the young of the short-spined sea scorpion Myoxocephalus scorpius, the five-bearded rockling Ciliata mustela and the lumpsucker Cyclopterus lumpus. From spring to autumn, the adults and juveniles of the broad nosed pipefish Syngnathus typhle, the sea stickleback Spinachia spinachia and the three-spined stickleback Gasterosteus aculeatus. In addition, various marine isopods, amphipods, shrimps, snails and various other juvenile fish can be found here. In shallow water, there are also frequent stands of the small seagrass Zostera nana. This plant is not an alga, but a flowering plant that has managed to establish itself in a marine habitat. There used to be very large stocks of Zostera on the German North Sea coast. At that time, the dried seaweed was used as filling material for beds. Nowadays, seagrass meadows have declined enormously, which is due to various factors. Animals such as sea sticklebacks, pipefish and seahorses in particular are perfectly adapted to the habitat of a seagrass meadow, as these species perfectly reproduce the stalks of seagrass swaying in the swells with their colouring and rocking way of moving. Depending on the subsoil, various types of seaweed can be found below the tide line in the North Sea, which on the one hand provide settlement areas for numerous animal species and on the other hand also offer food. This zone, which no longer dries out at low tide, is generally referred to as the sublittoral. However, the areas that can be colonised by algae are limited by the water depth, as light is only available in such small quantities at greater depths that plants can no longer grow and carry out photosynthesis there.

Most red algae manage with very little light and are therefore also present at greater depths than brown or green algae. This is why red algae are usually the better algae for aquariums, where they can continue to grow very well and can be cultivated easily, unlike seaweeds and laminaria. The seaweed that can be found in the rinsing fringe gives some information about what the sublittoral bottom is covered with and whether it is a hard or soft bottom habitat. Recently, it has been observed that some algal species have become truly globalised. For example, the terete wart weed Gracilaria vermiculophylla, which originally came to us from the North Pacific. The same goes for the wireweed Sargassum muticum, whose origins probably lie in Japan, and which is now in the process of conquering the rest of the planet's oceans... We can often only guess what the medium- and long-term consequences will be for our endemic algae species. In any case, the invasion of animals and plants from other parts of the world's one large ocean should always be critically observed.

High Seas

High seas; drifting algae live here, some of which are distributed worldwide.

Wireweed (Sargassum muticum). This alga originates from the Northern Pacific!

This habitat does not exist in the North Sea in the true sense of the word, as the North Sea is a relatively shallow shelf sea with an average depth of only 94 metres. Its deepest point is 725 metres deep and lies in the Norwegian Channel. The shallowest point is only 15 metres deep and is located at Dogger Bank, which lies off the English coast. Therefore, we understand this to mean the areas somewhat removed from the coast, which are no longer subject to the direct influence of the tides. This habitat is characterised by a great abundance of animal and plant plankton, so that the North Sea water always appears slightly turbid and greenish-brown. These micro-organisms are the food basis for all other inhabitants of the high seas, regardless of whether they live here permanently or are only passing through on their way to other marine regions. Some high seas creatures are doomed to die if the current carries them close to beaches or coasts, such as the many different species of jellyfish. The salinity is highest in this part of the North Sea, at 34-35 per mille, because near the coast the sea is subject to the influence of numerous freshwater inputs from rivers and precipitation, which can, for example, pelt the dry mudflats. Here, the salinity is only about 30 per mille. The zone in which the fish glide through the free water is also called the pelagial, which is demarcated from the benthos, the bottom. Pelagic fish usually have a very high energy requirement and therefore have to eat everything that comes in front of their mouths. It is therefore not uncommon for sea anglers to often pull large numbers of schooling fish of the same species out of the water at one fishing spot. Typical inhabitants of the pelagic are garfish Belone belone, mackerel Scomber scombrus, herring Clupea harengus, spiny dogfish Squalus acanthias and halibut Hippoglossus hippoglossus. Invertebrates found here are mainly microscopic plankton and jellyfish, such as the compass jellyfish Chrysaora hysoscella and the moon jellyfish Aurelia aurita.

Mysid shrimps of the order Mysida and planktonic krill of the order Euphausiacea also play an important role in this system and even serve as food for large baleen whales or basking sharks.

Cultivators and Neozoans in the Harbour Habitat

A typical little harbour on the German North Sea coast.

Sheet pile wall in the harbour, overgrown with introduced giant Pacific oysters (Magallana gigas).

Harbours are characterised by the fact that they are subject to various influences that limit life for pure marine life. These limits consist of fluctuating salinities, contamination of the water and harbour mud, and sometimes very extreme current and tidal influences. Therefore, only organisms that are able to adapt to these conditions can settle in this habitat. Sometimes organisms from deeper water layers are also carried into the harbours by fishermen, so that even here you can "find" them with a sink net. In a typical North Sea harbour, you can often find sticklebacks, gobies, pipefish, flatfish, eelpout and eels. In terms of invertebrates, you will find a rich variety of sea worms, sea anemones, crabs, shrimps, echinoderms, mussels, snails and sponges. Among them are species such as the shore crab, the barnacle, the mitten crab, the sea conch, the edible crab, the small rock shrimp, the periwinkle, the breadcrumb sponge, the common starfish, the blue mussel or the Pacific giant oyster, which has been introduced here by oyster farms. Mussels often colonise the sheet pile walls to which they attach themselves with their byssus threads. The oysters even fuse their lower half of the shell to the sheet pile wall; often they even overgrow the barnacles and displace the mussels. Animals from harbour areas are generally no longer edible for humans because they can be contaminated with oil, pesticides or heavy metals such as cadmium or mercury. Therefore, depending on the degree of contamination, animals caught here are at best still usable as animal feed or as stocking animals for aquariums. As the sheet pile walls of harbours offer only few structures, the same biological diversity cannot be found here as for example in estuaries or on mussel beds.

Sheet pile wall of a harbour with oysters and barnacles during the low tide. These animals belong to the toughest kinds of sea-animals, which are able to settle on all kinds of extreme places.

Block and Boulder Bottom

The European edible sea urchin and spiny starfish prefer this habitat.

The Norway king crab Lithodes maja seeks cover and prey here.

This habitat, rich in structures, is characterised by the fact that all kinds of small animals can attach themselves between the accumulations of stones and boulders. These include in particular mussels, worms, echinoderms, sponges, as well as various actinia and corals. These often sessile invertebrates in turn form the food base for larger crabs and fish. Block and boulder bottoms discourage most trawlers from dragging their nets over the bottom here, as they would run a great risk of damaging or losing their fishing gear in these places. Thus, this habitat is also a refuge for species that have been overfished elsewhere. Therefore, these refuges can provide strong impulses for recolonisation of overfished areas if fishing is limited. Block and boulder beds are not found on the German North Sea coast, but they are found near Helgoland and on the Danish and British cliffs. These rocks provide support and settlement space for marine creatures that have drifted here as larvae with the current from other marine areas. Such animals cannot develop properly without solid substrates, let alone stay on the bottom. These animals include, for example, various sea urchins, starfish and soft corals, but also species such as edible crabs and even king crabs. In the absence of hard grounds, some of these organisms also settle on man-made groynes, but groynes are only suitable habitats for a fraction of these species, because they are subject to a very strong tidal influence. And furthermore, as shallow water biotopes, they are exposed to excessively high temperatures in summer. Therefore, small true crabs (Cancer pagurus) might be found on a groyn, but not animals like the cold-loving Norway king crab Lithodes maja, which needs it preferably colder than 8° Celsius. The jagged rocks offer excellent hiding places for predators such as the devilfish Lophius piscatorius, and caves and crevices are home to numerous crustaceans such as the squat lobster Galathea squamifera, the European lobster Homarus gammarus, the spiny lobster Palinurus elephas or the great spider crab Maja brachydactyla. But their enemies are also on the agenda here: The common octopus Octopus vulgaris and the lesser octopus Eledone cirrhosa. And their predators, such as the cod Gadus morhua, the ling Molva molva, or the green pollack Pollachius pollachius are of course not far away either... Higher marine algae can often anchor themselves between the rocky debris with their adhesive roots, the so-called thalli. These algae, also known as Laminaria, often grow very quickly, with some species reaching several metres in length. These algae often harbour animals, which are adapted to cling specifically to the algae leaves and also use them as a protein-rich food source. In Japan, these algae have long been used as food for humans, and on Heligoland there is even a station for researching and using the algae. Some can even be eaten like lettuce. Unfortunately, Laminaria can only be kept for a few weeks to months in aquaria according to the current state of the art, and it is not yet known exactly what the reason might be. There is still a great need for research here. However, dedicated hobbyists have already become active in this field, and some have already succeeded in getting seaweed to grow according to its natural rhythms by simulating days of different lengths and adjusting temperatures accordingly. A few seawater aquarists have even devoted themselves entirely to keeping and cultivating macroalgae. However, a recent development observed by biologists at the Max Planck Institute on Heligoland must be regarded as alarming. Through decades of observing large brown seaweeds, they noticed, that they have begun to settle at ever greater depths. This is apparently related to the fact that they retreat from the surface water warmed by anthropogenic influences. At some point, however, they can no longer retreat, because they would otherwise get too little light. A largescale disappearance of the Laminaria would be the consequence, with various animal species of this special ecosystem following on its heels! This sad phenomenon has already been observed off the Spanish Atlantic coast along a coastline of about 150 kilometres. Therefore, we can no longer afford to continue ignoring Mother Nature's warning signs to us!

Wrecks

Sunken ships offer retreats for various species, especially in places where otherwise muddy ground or sandy substrates predominate. After some time, some wrecks are so populated with a wide variety of sitter species that they are hardly recognisable as structures of human origin. However, some wrecks are also sources of danger for their new inhabitants, because they contain, for example, waste oil, poisons and other hazardous substances that can get into the water and contaminate the environment if their storage containers are rusted through. In particular, sunken ammunition transporters from the First and Second World Wars, sunken nuclear submarines and freighters carrying hazardous chemicals are literally ticking time bombs. This is particularly worrying when humans use fish and marine animals from the vicinity of such contaminated shipwrecks for their food. In the North Atlantic, wrecks are home to invertebrates such as various species of sea anemones, mussels, barnacles and tubeworms. These in turn attract various other species, such as all kinds of crustaceans. Many a lobster or langoustine has also found a home in a wreck. And after them, certain large fish such as cod, pollack, rockfish and conger eel take up residence here. For this reason, wrecks are often popular destinations for divers and sea anglers. Divers should be very careful, however, as wrecks can harbour many sources of danger that are not always calculable. In the course of increasing shipping traffic in the North Sea, the number of shipwrecks will increase considerably in the foreseeable future, and these artificial reefs will provide good settlement areas for many marine organisms. However, accidents such as the wreck of the timber freighter Pallas off the island of Amrum have shown that even cargo ships not carrying petroleum or chemical products pose an enormous risk to marine fauna with their own waste oil alone. Wrecks often attract large fish and provide settlement areas for numerous invertebrates. Nowadays, unfortunately, wrecks mostly consist of corroding metal parts. And also various plastic debris that, due to the lack of ultraviolet light, does not decay on the seabed and is thus preserved for posterity for eternity...

The Inhabitants of Sandy Bottoms

Sandbottoms consist of the finest sediments, which are formed from finely ground stones, mussel shells and other calcareous skeletons of a wide variety of organisms, such as various echinoderms and foraminifera. Due to storms and the associated currents, the sandbanks of the shallow water zone are constantly shifting, so that new sandbanks and islands are constantly being formed and old ones are shifting or sinking back into the sea. Only one law applies to this natural rhythm: the only constant is change! The inhabitants of the sandy bottom are adapted to hiding, burrowing or camouflaging themselves in this low cover environment. Many species only come to the sand surface at night to minimise their risk of falling prey to predators. In addition, many invertebrates in particular can regenerate amazingly well if they have lost a leg or a body segment to a predator. The eternal law of eating and being eaten rules here with relentless harshness. The sandy bottom habitat already begins in the shallow water area, which is exposed to the direct influence of the tides, and extends away from mussel beds, mud or boulder bottoms below the tide mark, usually to depths of about 5-25 metres. This habitat is very important for German coastal fisheries, as it is mainly in this depth range that the bottom is ploughed up by shrimp-trawlers hunting for the North Sea shrimp Crangon crangon, the plaice Pleuronectes platessa or the sole Solea solea with their trawl nets. And especially in summer, species such as various gurnards, squid or dogfish also hunt for small bottom-dwelling animals here. For the sharks, the shallow sandy bottoms of the North Sea serve as a nursery, as they give birth to their live young here.

Heligoland & Rocky Coasts

As the only German rocky island in the North Sea, the island of Heligoland is home to a unique fauna and flora of organisms, which cannot be observed in this diversity anywhere else on the German North Sea coast. The spectrum ranges from organisms that are specially adapted to the rocks to creatures that migrate through the high seas and even marine mammals that would otherwise hardly be seen. The different habitats range from the cliffs of the splash zone to Laminaria-forests and reefs, where such bizarre creatures as the king crab and dead man's fingers can be found. The most typical animal, however, and to a certain extent the heraldic animal of the island of Heligoland, is the European lobster. Which is said to have been so common in ancient times, that surplus catches were used as fertiliser. Other typical animals of Heligoland include edible sea urchin Echinus esculentus, sun star Crossaster paposus, dahlia-anemone Urticina felina, beadlet anemone Actinia equina, dead man's fingers Alcyonium digitatum, lumpsucker Cyclopterus lumpus, gilthead sea bream Sparus aurata and bib Trisopterus luscus. Even this small excerpt shows, how many different zoological orders the fauna of this unique habitat is recruited from; of course, it is not nearly possible to accommodate all the creatures found there in an aquarium - no matter how large it is.

The landmark of Heligoland is the European lobster!

Mussel Beds

Mussel beds exist, where mussels attach themselves to the substrate with their byssus threads. Where there are no hard substrates, they simply stick to each other and form firm settlement felts that can defy the strong current. Their byssus threads are difficult to tear and adhere to the substrate after only a few minutes. Mussels are often found in exposed places, such as on groynes or on wooden piles, where they dry out at low tide. This allows them to escape the starfish that can no longer follow them here at low tide, but exposes them to the danger of becoming the victim of heat, cold or seabirds. The mussels counteract high heat by opening their shells a little and spitting out some water, which then creates evaporative cooling. Mussel beds provide a habitat for many animals that would hardly have any cover without the mussels. For example, worms, snails, various crustaceans and starfish can be found here. Thus, the mussels take over an ecological niche that corresponds to that of the corals in the tropical seas. In addition, even the dead mussels still make an important contribution to other animals, as these can also settle on their empty shells. The current then gradually grinds them together over the years, creating sand and silicates. These are drifted by the current and form new sandbanks and islands. The small animals and fouling organisms are then followed by larger animals that feed on them. The mussel reefs thus form the food basis for numerous echinoderms as well as various species of crustaceans and fish. Without these reefs, biological diversity and productivity in the North Sea would be considerably lower. Finally, it should be noted that reefs of the introduced Pacific giant oyster Magallana gigas (picture below) have recently begun to form on the German North Sea coast. Only time will tell what consequences this will have for the North Sea ecosystem.

Restless Wanderers between different Waters

Many animals that live in the North Sea spend only part of their lives here. They are not fixed to a constant habitat. At least four types of life strategies can be distinguished: Catadromous species migrate from freshwater to the sea to spawn. Anadromous species migrate from the sea to freshwater to spawn. Endemic species stay in the sea their whole life, but change their residence places in the North Sea during their life. Cosmopolitan species migrate in the sea around the entire globe; some are climate-dependent, so that one speaks of circumpolar or circumtropical species. The catadromous and anadromous fish species of the North Sea have the ability to switch from freshwater to the sea and vice versa by means of special glands and osmosis-resistant body tissue. Osmosis is the unidirectional diffusion of a substance through a semi-permeable membrane. This means that salt dissolved in seawater withdraws water from the tissues of an animal living in it. Conversely, in fresh water, water penetrates the tissue of the animals living there. This process of adjustment to the surrounding environment is also called vapour pressure gradient. Most aquatic animals are not able to compensate for a rapid change in this gradient in the short term. This means that their body cells are literally shredded by a short-term change in the salinity of the surrounding water. Invertebrates in particular usually do not survive density fluctuations for long, while some fish, for example, can even survive a transfer from fresh to salt water for several days. Freshwater fish urinate constantly to remove excess water from their bodies, while marine fish have to drink constantly to compensate for the loss of water due to the dehydrating salt in seawater. They excrete the too much salt they have taken in via their gills and kidneys by means of special salt glands. A few species have managed to perform all these bodily functions. Therefore, they can often tolerate extreme changes from a salty to a low-salt environment and vice versa. It is as if they only need to flip a switch in their body to switch from freshwater operation of their organism to seawater operation and vice versa. These life artists include not only fish such as eel, salmon, sea trout, North Sea houting, flounder, sturgeon and smelt, but also invertebrates such as the mitten crab and the brackish water shrimp. Even this short list shows that in our latitudes there are more fish than invertebrates that can manage this enormous change in their metabolism in the short term. Finally, there are also trends in various species that make it easy to see that marine species are evolving into freshwater species. Many freshwater species can be directly derived from marine ancestors and there are even species of which freshwater and seawater strains exist independently of each other. These are then referred to as primary and secondary freshwater species. A typical example of a primary freshwater species would be the carp, while the three-spined stickleback is a secondary species, of which there are also true saltwater strains.

The Houting Coregonus oxyrinchus is considered extinct due to the construction of its spawning grounds in the North Sea.

Stray Visitors of the North Sea and the Baltic Sea

Stray visitors are animal species that usually occur only sporadically or temporarily in areas other than their usual range. Stray visitors should be clearly distinguished from the migratory forms of some species and from the introduced species, the neozoans. The distinction is very simple: migratory species regularly occur every year in the same areas at certain times of the year and/or under certain weather conditions. A typical example would be the sand-smelt Atherina presbyter, whose juveniles migrate northwards from the southern North Sea during the summer. Neozoans, on the other hand, originate from other parts of the world, but have been able to establish themselves permanently in the North Sea due to optimal living conditions. An example of this are species such as the mitten crab Eriocheir sinensis, which was introduced into our inland waters from China at the beginning of the twentieth century, and which migrates back to the North Sea to reproduce. The mitten crab has even been so successful that it has made Lake Constance, far from the sea, its habitat! Stray guests, on the other hand, usually appear out of nowhere, stay for a few weeks or months and then disappear again. Their existence often even goes unnoticed, unless they are landed as accidental bycatch and scientifically studied. Unlike migratory species, they do not regularly visit foreign waters, and they do not establish themselves here the way neozoans do. Typical stray guests of the North Sea are species such as swordfish Xiphias gladius, Moroccan sea bream Dentex maroccanus, stingray Dasyatis pastinaca and electric ray Torpedo marmorata. The marbled swimming crab Portumnus latipes can also be counted as a stray, as it actually prefers warmer southern waters and is most common in North African waters. On the marine mammal side, fin whales and dolphins have also been sighted in the Baltic Sea, as well as sperm whales and belugas in the North Sea, which have strayed to us from Arctic waters. A duck whale has also strayed into North German waters - its skeleton was even exhibited for a time in the Landesmuseum in Hanover. Species such as the sea bass, which thanks to human intervention found their way into the North Sea by escaping from aquacultures, are more likely to be classified as neozoans. As a result of global warming, southern species are also on the advance, such as the thresher shark Alopias vulpinus, which has already been landed off the Dutch coast. The mullet Mullus surmuletus also belongs to this group, which has advanced from the English Channel to the Elbe estuary due to warmer waters. As the mullet has already established itself in more northerly climes, it can no longer be considered a true stray visitor; the thresher shark, on the other hand, can, as it is not regularly sighted in the North Sea. The sudden appearance of subtropical and tropical species in the North Sea is a warning sign to us!

The subtropical thresher shark Alopias vulpinus has also been caught off the Dutch coast. Here is a model of this shark species. Although it can grow up to 6 metres long, it is harmless to humans because it only circles small fish with its long tail and then strikes them as prey. But it indicates the climate change!

Temporary Sandbank Habitat

This marine habitat is probably the most extreme place imaginable to eke out an existence. Most people imagine a beach as a pleasant place to spend their holidays, where they can enjoy the mix of wind, sun and seawater and engage in some leisure activity. For the creatures that naturally inhabit a beach, however, the situation is quite different. They have to withstand icy winds and sandstorms, they have to endure heat and cold, and they have to cope with the problem of acquiring food and maintaining their species. Very few species have mastered all these problems through special adaptations to this extreme environment. In addition, this habitat is subject to constant change. The tides alternate between dryness and flooding, and the inhabitants of a sandbank must be able to cope with both aggregate states of their habitat. They have to cope with particularly extreme tides as well as particularly extreme seasons. In particular, they are exposed to all kinds of precipitation on their sandbank without shelter, ranging from rain to hail to snow. Also, in winter, the ground can freeze, and in rare extreme years, ice floes can even form. Finally, it should be mentioned that, as a result of a storm surge or a hurricane, the sandbank can simply be washed away at any time, so that its inhabitants have to look for a new dry place afterwards. The only constant in this habitat is the permanent change!