Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

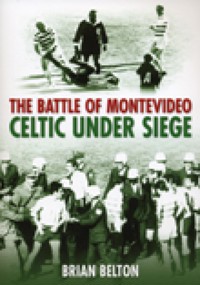

The 1967 World Club Championship decider between Celtic and Racing Club of Buenos Aires was one of the most violent and controversial matches of all time. Three Celtic players and two from Racing Club were sent off in total. The game descended into farce, with the Uruguayan police forced to take to the pitch with batons to separate brawling players. Pictures released of the match met with shock worldwide, but while an embarrassed Jock Stein fined his players, those from Racing Club were rewarded with a new car each! This book tells the story of a real clash of two very different footballing cultures.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 231

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2008

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

THE BATTLE OF MONTEVIDEO

CELTIC UNDER SIEGE

THE BATTLE OF MONTEVIDEO

CELTIC UNDER SIEGE

BRIAN BELTON

To Ronnie Simpson – Lion, Gentleman, Inspiration.

First published in 2008 by STADIA

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2013

All rights reserved

© Brian Belton, 2008, 2013

The right of Brian Belton to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUBISBN 978 0 7509 5676 5

Original typesetting by The History Press

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

Foreword

Introduction

one

Continental Champions

two

Football in the Blood

three

To Avellaneda

four

On Yer Heed, Ron!

five

Football Missionaries

six

The Gathering Storm

seven

Belly of the Beast

eight

Battle Lines Drawn

nine

Under Siege

ten

So Far Away

eleven

Goodbye Ronnie

twelve

Football in Argentina Post-1967

thirteen

After Montevideo

fourteen

Conclusion

Bibliography

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Every reasonable effort has been made to acknowledge the ownership of copyright material included in this book. Any errors that have inadvertently occurred will be corrected in subsequent editions provided notification is sent to the publisher.

Celtic fetch their goalposts, 7 September 1967.

FOREWORD

‘Jimmy McGrory brought me to Celtic. He laid the foundations of what Celtic did later. He knows the club inside out’ – Ronnie Simpson

Between 1922 and 1937, Jimmy McGrory scored 397 league goals for Celtic. He was the Scottish league’s top goalscorer in 1926/1927, 1927/1928 and 1935/1936. During his career he scored 550 goals in first-class matches, including 410 goals in 408 league games, making him the most prolific scorer in British football history.

From the end of the 1940s until Jock Stein took over in 1965, Jimmy was manager of Celtic. He then became the club’s public relations officer until he retired. Being born in the East End of Glasgow he had life-long experience of Celtic and worked for the club for close to half a century.

At the end of 1976 I wrote to Jimmy McGrory (as well as several other former Celtic players, care of the club) asking for their views about Celtic’s 1967 bid for the World Club Cup. I have included Jimmy’s reply as a foreword as it was the longest and, I think, the most insightful of the four replies I received. But also, both as a player and manager with Celtic, Jimmy was known to ‘set the highest standards of fair play and sportsmanship that could be expected of any player’.

It has been almost ten years since Celtic met Racing Club of Argentina in the Intercontinental Cup to see who might become the club champions of the world. There were three meetings between the two clubs and they were memorable although a lot of people, particularly in Glasgow, wish that they were memorable for better reasons.

Much has been said and written about those meetings – perhaps most about the one in Uruguay – so there is not much point in going over that ground. The record will say that Celtic lost the football match, but I am not sure there was a great deal of football played in any of the meetings between the two sides. The Argentinians did not want to play a game; they wanted to fight a battle. But that has been said by many people in many different ways and maybe now it is time to see what can be got from the experience more than going over the same ground again.

Clubs either choose to take part in these type of events or they do not and there is always a great deal at stake. But in Glasgow it is always has been, and is always going to be, more important for Celtic to win when they play Rangers than it is to go hundreds of miles away to play one team for a trophy that people do not know much about. You might say that in Glasgow the world champions are the winners out of Celtic and Rangers.

But if the club plays the game it should do its best to win by the rules. If the other side do not want that, the club should simply not play. That is very simple and fair.

That might be a lesson Celtic learned from its meetings with Racing Club.

I am not sure if two teams and two or three games make a world championship or what being able to say that a team are world champions is worth. For Celtic supporters, Celtic will always be the best team in the world and no trophy will prove that better or less. The idea is that if Celtic does not win, the team will win the next time. Football might be about winning, but it is more about the hope of winning. If Celtic were guaranteed to win every game there would not be much point in coming to watch games. Successful teams know that losing is not an end in itself but a lesson in how they might win. That probably is the biggest lesson to be learned from Celtic’s experience in South America in 1967. That is what I hope.

Jimmy McGrory,

writing in 1977

The Mighty Celts.

CUPS, COPA, TROPHIES

Throughout this book what might be generically understood as the World Club Cup is also referred to as the Intercontinental Cup, the Copa Libertadores, the Copa Libertadores de América and the Copa Intercontinental, according to context.

The Copa America is the South American Nations Cup which also has a history under various titles (the Campeonato Sudamericano de Selecciones for instance) and these will become clear in the reading.

The first official team photograph of the 1966/1967 season at Celtic Park. They are pictured posing with nine of Celtic’s trophies: the Ibrox Disaster Cup,Victory Cup, St Mungo Cup, Coronation Cup, Scottish League Championship, Scottish League Cup, Second XI Cup, Empire Cup, Exhibition Trophy and the Glasgow Cup.

INTRODUCTION

‘The artist cannot attain to mastery in his art, unless he is endowed in the highest degree with the faculty of invention’ – Charles Rennie Mackintosh, architect, born 70 Parson Street, St Rollox, Glasgow

INTERCONTINENTAL CUP – FIRST LEG:

Date:

18 October 1967

Venue:

Hampden Park, Glasgow

Referee:

Juan Gardeazábal (Spain)

Attendance:

84,437

Celtic FC (Scotland)

1-0

Racing Club de Avellaneda (Argentina)

Goal: McNeill

Ronald Campbell Simpson

1

Agustín Mario Cejas

James Philip Craig

2

Roberto Alfredo Perfumo

Thomas Gemmell

3

Rubén Osvaldo Díaz

Robert Murdoch

4

Oscar Raimundo Martín (c),

William McNeill (c)

5

Miguel Ángel Mori

John Clark

6

Alfio Basile

James Connolly Johnstone

7

Norberto Santiago Raffo

Robert Lennox

8

Juan Carlos Rulli

William Semple Brown Wallace

9

Juan Carlos Cárdenas

Robert Auld

10

Juan José Rodríguez

John Hughes

11

Humberto Dionisio Maschio

The Celtic and Racing Club captains shake hands before the kick-off of the first leg in Glasgow, 18 October 1967.

Jimmy Johnstone, a Celtic legend.

Official match programme from the Celtic v. Racing Club match at Hampden Park on 18 October 1967.

The game began the way it would continue to the end. In the eighth minute, the home side made what looked like a justified appeal for a penalty. Well inside the box, Basile had scythed down Johnstone. However, Señor Gardeazábal gave a free-kick, inexplicably on the edge of the penalty area. A few minutes after this, Racing Club’s goalkeeper provoked a huge bellow of anger and contempt from the crowd. He thrashed about in seemingly excruciating pain on the six-yard line following a challenge by McNeill after the clearance of a corner kick. Only seconds later Cejas denied Auld with a fine save executed with great theatrics, demonstrating phenomenal healing powers from the apparently near-fatal damage he had experienced an instant before.

The referee was also an early victim of Racing. He awarded a sequence of free-kicks to the home side but appeared taciturn when it came to imposing more stern discipline on the visiting side as they upped the physical level of their game to toxic proportions that more than a few times warranted the offender’s dismissal. It was clear that the Racing players were taking turns of duty to target and effectively mug the Celtic men. This gave Señor Gardeazábal a difficult challenge as far as isolating individual perpetrators of wrongdoing. This being the case, the South Americans aggravated the Scots by fragmenting any attack directly at its foundation, dislocating potential progression of play and/or preventing Celtic from developing an effective pattern of forward movement.

The game had its ups and downs in South America.

This showed that Racing had fears that they lacked the character to face Celtic in open, flowing play but it produced a match that faltered between fractured events, created by blatant time-wasting, consistent fouling, hold-ups for the treatment of ‘injury’ and arguments about refereeing decisions. All this resulted in Celtic being frustrated and therefore distracted.

Racing Club’s defence and midfield seemed to know no bounds in their aggression. There was fifteen minutes of the first half left to go when Bobby Murdoch was the victim of first one and then another atrocious, purposeful foul. He was hurt and his effectiveness had plainly been diminished. This was more than unusual, as Bob was noted for his power, resilience and intelligent application. However, he was an obvious target as the pivot of Celtic’s frontline; slow or stop him and you would hit his team hard. It was pretty obvious that the Argentines knew that.

Over five-dozen fouls were acted on by the referee, most were for infringements against Celtic. Johnstone got the worse of it, although he hurdled over mad tackles aimed at him like missiles and dodged a hail of swiping kicks, but of course more than a few of his assailants hit their target. This demonstrated that Jinky scared the South Americans to death and, despite the concerted attack on him, he showed himself as the master of the combined assassination force and he was a constant source of anxiety for the visitors.

Johnstone, Lennox, Murdoch and O’Neill at the Victoria Plaza hotel, Montevideo.

Rubén Díaz had been given the daunting assignment of shadowing Johnstone, a huge responsibility given that Jimmy was seen as Celtic’s most potent weapon by the Argentines. An accomplished man-marker on the left, Díaz was tough but also intelligent and versatile, being able to play almost anywhere in defence. As such he was quite a significant figure in the Racing side. Born in Buenos Aires on 1 January 1964, Rubén Oswaldo Díaz Figueras was nicknamed Panadero (baker) as his father was the owner of a bakery, and he began his professional career with Racing in 1965. He was a member of the side that claimed the Argentinian League Championship in 1966 and the team that were victorious in the Copa Libertadores the following year.

However, although Díaz followed the Celtic winger wherever he went, the defender was totally outclassed by ‘Wee Jimmy’. He was consistently reduced to try and tackle Johnstone prior to him receiving the ball, or lurk until the final fraction of a second in order to assess whether to plough into his target or allow one of his colleagues to bushwhack the ‘Viewpark Wizard’ (none of whom were better at stopping James Connolly Johnstone than Rubén the Ripper).

While Johnstone’s treatment was the cause of much outrage amongst the Celtic fans, a specific episode incensed the watching Glaswegians. Jimmy had coaxed the ball to the right touchline and tore beyond Juan Carlos Rulli, but in a moment that mixed anxiety with brutality in the South American, he dived into the Celtic winger with the latest of late tackles. Before Jimmy hit the ground Oscar Martín was on him, executing a sickening plunge with feet and knees that made contact with Johnstone at waist height.

Playing for Scotland against England, Jimmy Johnstone demonstrates the skills that led to him being targeted by Racing Club.

As a consequence of this double broadside on the Celtic flankman, a colossal scrum ensued between the players of both teams. This proved to be a great distracting tactic that allowed Martín to make himself scarce immediately after making contact with his prey. While the fracas continued, Jimmy lay motionless. The only punishment for the bullying malevolence was a warning for Rulli.

Throughout the first half Billy McNeill – taking a prominent role in set-pieces – had been a consistent threat. Ten minutes into the second half it was he who so nearly broke the stalemate. He made contact with Auld’s free-kick and almost gave his team a well-deserved lead, flicking a snappy header goalward, only to be denied by the post.

But the home skipper was up for the corner kick from the right with twenty minutes of the game to play. John Hughes dug in a towering but penetrative cross and it was sweetly met by Parkhead’s very own Caesar. He soared imperially to make a lengthy, arching header. The goal was just reward for Billy, as every time he had moved in on a set piece he had been hampered, bumped, buffeted, held, pushed, and generally obstructed. McNeill was overjoyed. As the ball rolled around at the rear of the net he was gesturing jubilantly in the direction of Basile. The Racing defender was also subject to some Glasgow vernacular that he probably didn’t totally understand but certainly gathered the meaning of. The motivation for this was evident when McNeill came off the park at the end of the game with a corking black eye by way of an Argentinian elbow that he had picked up as he prepared for the Hughes corner.

Ronnie Simpson still asleep at breakfast? Buenos Aires, October 1967.

Celtic did all they knew to find a second goal but on eighty minutes the Argentines began to risk an offensive. The way they went about this contradicted everything they had done up to that point. Their passing was immaculate and for the first time they posed the Celtic defence some real problems. In a hectic five minutes Celtic’s defence was twice breached. Basile, fortunate to still be in the game given his unrelenting foul play, sent a fierce drive over the bar when he might have scored and in the final sixty seconds Rodríguez, from close range, struck the ball straight at Ronnie Simpson. The keeper did well to spread himself to stop the shot. But in the end, Racing ran out of time.

As an exhibition of sporting competition the first Intercontinental Cup game between Celtic and Racing Club had some worth. However, as an example of what a football match might be – especially a game that was for a world crown – to call it less than distinguished would be overstating its merit. For the most part, the Argentines sent the ball everywhere and anywhere with ruthless desperation, although on a few occasions they did manage to work the ball out of defence with commendable technique and notable skill.

The Celtic defence, although hardly tested before the dying moments of the game, could not be faulted. They held fast when they might have been drawn into running at their opponents’ goal in frustration. They concentrated on vigilant and sensible marking, occasionally allowing McNeill to add his weight to the attack for corner kicks.

The inability of the referee to get to grips with the situation, together with the cynical attitude of the South Americans, destroyed any chance of making the encounter one to remember in terms of its aesthetic excellence. Racing appeared ready to go to any lengths just to stop Celtic and grab the advantage for the fixture back in Avellaneda. This attitude had much in common with most Argentinian football teams, both in the domestic leagues and the national side. The will to win, even by means that push the boundaries of acceptable sporting behaviour, is ingrained. The Argentine professional is brought up with this and there is no need for a manager to pursue players to adopt this attitude; by the time they have broken into first-class football they have infused the directive as part of the game’s culture in Argentina. To British and probably European eyes, the type and level of fouling can seem pusillanimous, indeed against everything that football is about. But, to judge anything through the lens of cultural norms is to express a bias. However, sometimes a bias is needed as the severe absence of the same in itself creates an alternative prejudice.

According to Ronnie Simpson, the Celtic goalkeeper in that game:

They were scared of us. Teams play dirty mostly because they can’t play, but that wasn’t the case with them. They could play well. The other reason why a team will play dirty is because they are frightened that the other team are better than them and they think the only way they can win is by cheating. I think that’s how they were thinking.

Even before the match they looked nervous. They either stared at you or couldn’t look you in the eye. I think they were scared before they got to Glasgow and even more frightened at Hampden Park. But that is what killed the game as entertainment. It was all very annoying. They were annoying.

During the whole course of the match, the Racing forwards hardly got within shooting distance of Simpson. Close to eighty minutes of the game was taken up with furious assaults on the Racing half. The few moments of what passed for Racing attrition (within the laws of the game) were pallid in comparison. This made Celtic look as if they were in total control, but of course, the South Americans did what they had set out to do and, with luck on their side, limited the home team to a single goal.

The Celtic fans left with mixed emotions. They were of course delighted to see their team win but were understandably worried that one goal would not be enough to take to Los Estadio Juan Domingo Perón. But many would also have been left perplexed by what they had seen. Racing had shown they were a side capable of footballing beauty but had chosen to lower themselves into a mire of viciousness. If this was what they were like away from their homeland, what would they be capable of in their own backyard?

After the match, the grey-haired Racing coach Juan Pizzuti declared: ‘We can do better than that. But that game is over now; it is completely finished and in the past.’

I started writing this book just over forty years ago now. It was inspired by the extraordinary events in a city far away and of course, long ago. And it does seem now like a legend or a myth, but one I lived, although looking back it has a dream-like quality. The notes I originally wrote have disintegrated – although they have been transcribed on almost every generation of computer – and others are barely comprehensible, written on cigarette packets from the 1970s, a bus ticket from the 1980s and beermats with a history too disjointed to put any definite dates to. I have school exercise books full of scibblings and pads of every description bought in places as far apart as Glasgow W.H. Smiths and the Hong Kong University. They were written on every habitable continent on the face of the Earth and at every hour of the day. I once talked to a former Celtic player and recorded his words in the spaces I could find on the pages of a Hearts match programme. On the way back to my hotel from the ground the skies above Edinburgh opened and a Caledonian Niagara seemed to fall directly on me. When I got to my room the programme that had been stuffed in the pocket of my jeans looked like a cross between the Dead Sea Scrolls and porridge. But I laid the mush on the radiator in the hope that, Lazarus-like, the words I had written would arise back into the world. The next day I had a brittle, chewed-up, papier-mâché frisbee that called itself ‘Midlo’ and my memory to call on. A frustrating combination as it turned out.

However, this process has not been non-stop. I have gone years without writing a word and in going back to the manuscript found that great lumps of it were either stupefyingly dull, vaguely incomprehensible, slightly mad or just plain wrong. There have been more re-writes than I dare to think about and the additions and subtractions would fill at least three other books. But, on the whole, I think it has been worth it. I have returned to Uruguay a few times since my first stay in 1967, and each time I go back I am struck how minutes can change years. Celtic and Racing Club have been a constant stream in my life and looking at the game they played in Montevideo has caused me to travel probably tens of thousands of miles and meet, speak to and exchange correspondence with some marvellously informative and insightful people. I have also met my share of idiots too and been sent down enough blind alleys and block turnings to challenge my sanity (and lose it at points).

Celtic players wait for the bus to take them to a training session at the El Centenario in Montevideo on 3 November 1967.

Amazing though it seems to me now, over the expanse of weeks months, years and decades this book has been fermenting, I have tried to get a grasp on what happened in one football game; an hour-and-a-half, a mere sliver of time. But just describing the match and a few impressions from players and fans – the usual way of telling the tale of ‘Rovers v. United’, or ‘Town v. Athletic’ – does not really do it with regard to what happened at El Centenario in November 1967.

The first meeting between Celtic and Racing Club took place just nine days after the death of Ernesto Guevara de la Serna, Che Guevara, an Argentine revolutionary whose inspiration had been a vision of a united Latin America, from Mexico to the Magellan Straits. What motivated Che – apart from his politics – was what he saw as a common cultural link that overcame what he interpreted as artificial differences between the nations of South America. But he also understood that the people of that great land mass had a shared history and social structure that had, to a certain extent, been defined by their relationship with continental Europe, who in turn depicted them as what might most straightforwardly be defined as ‘estranged’. This cultural rupture was made manifest in the 1967 matches between Celtic and Racing Club. But it was heightened by the fact that, despite some level of religious affinity, the traditions and background that made – and were made by – Celtic were relatively remote from the Latin states of Europe – chiefly Portugal and Spain – that had influenced South American identity.

Tommy Gemmell says adiós – Celtic players taking the bus from the Victoria Plaza hotel en route to a training session.

Celtic came to South America as complete and utter foreigners, engulfed in a culture so far from Glasgow and its districts, the area that the Celtic players called home. Much the same might be claimed by the Racing players on their visit to Scotland, but in fact they had a much better idea of what to expect in Europe than the Scots had of what South America held in store for them. For starters, Racing expected Celtic to abide by the laws of association football in Glasgow, and they did. Celtic, of course, assumed more or less the same of Racing when they arrived in South America, but they didn’t get what they expected. Neither did they get what they expected from hotels and changing rooms, and they got more than what they expected from the crowd, including the missile that put Ronnie Simpson out of the second leg and the play-off.

Billy O’Neill catches up on some light reading, while flanked by Bobby Lennox and Bobby Murdoch.

Celtic were brought to South America by a game and that was the one tangible structure, held together by rules and conventions, that the travelling Scotsmen would have hoped to identify with, or at least they expected to make those considerations a means to get to know the places they would have to overcome or, more realistically, needed to conquer. But as history has shown, that ‘bridge’ of activity they quite understandably had anticipated to connect them with the alien world they had been transported to was itself imbrued with influences and attitudes they had no means of comprehending or dealing with in any ‘reasonable’ way.

As far as Celtic were concerned they were, in terms of their footballing environment, isolated in a mad place full of boggling insanity and populated by starey-eyed lunatics, foaming with simmering aggression that sporadically and unpredictably boiled over into raw hatred and naked violence. Strangers in a strange land, they were surrounded; under siege physically, geographically, spiritually and psychologically.

The portrayal of this condition has presented the most challenging of tasks to me as a writer and researcher. Tom Campbell’s fantastic book Tears in Argentina, along with the biographies of Jock Stein and the Celtic players who went to South America in 1967, to try to gain the recognition they undoubtedly had a right to claim – to be known officially as the best club side on the planet – have more than ably described events and certain points of view. At the same time, the lives of Stein and the Bhoys that faced Racing have become intimately known by the club’s fans, the football public and have even become the stuff of general knowledge and the folklore of popular culture. This being the case, I have never had the ambition to replicate any of this material.

The Battle of Montevideo seeks to give the reader a sense of the suffocating milieu Celtic entered into in 1967 and of how the blockade the Glaswegians found themselves in was nurtured by the host environment. This means developing some understanding of the nature of South American football and, in particular, its Argentine and Uruguayan incarnations, the specific contexts Celtic had to attempt to impose themselves.

At first, Celtic were greeted with curiosity in Argentina. But that fascination was more akin to: ‘What do they think they are doing, coming here?’ This was accentuated by the deeply observational gaze of a foe studying an enemy, trying to gain clues about how to destroy them from the ‘tells’ of demeanour. In Uruguay, the treatment that the Scotsmen experienced was more ambiguous.

In Montevideo, Argentina are indeed the old rivals on a number of fronts. Uruguay is, in terms of economics, population size and, to a certain extent, geography, a Latin American Scotland to Argentina’s England. Certainly, with regard to football, the enmity between the two nations is at least on a par with that which exists between the two full nations that sit, with their uneasy history, side-by-side in the body of Britain. But, for many of us that populate the islands hazily called the ‘United Kingdom’, the animosity between Scotland and England is mostly ‘personal’. Yes, if Manchester United were playing Estudiantes de La Plata at Hampden many Scots would throw their support behind the Argentines, but there would, at least for some, be something linked to language, values, political affinities, spiritual congregations, vicinity, history, attitude and culture that would make this affinity with Estudiantes just a little invidious. This might be even more the case (as it is probably less odious for a suppressing nation to give moral support to those it oppresses than the other way round) if, at Stamford Bridge, Rangers were obliged to meet and beat Peñarol.