Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

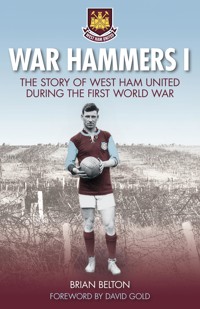

This book tells the fascinating story of West Ham United Football Club during the First World War, charting the relationship between war and football by following the pursuits of West Ham from 1913/14 to 1918/19. In many ways, it was their success in wartime competitions that led to them being accepted into the Football League in 1919, paving the way for subsequent FA Cup and League success. As well as a football story, this book is about the impact of the war on Britain. It documents the social implications of war on Londoners and the social and political influence of football, the armed forces and civilians alike. Looking closely at the 13th Service Battalion, also known as the 'West Ham Pals', the book includes such players as George Kay, Ted Hufton, and their manager and coach, Syd King and Charlie Paynter respectively.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 339

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Title

Preface

Foreword

Introduction

ONE The First Thunder

TWO To the Magpies’ Nest

THREE Football Goes to War

FOUR The Footballer’s Battalion

FIVE The Game of Dark Days

SIX Dangerous Danny Shea

SEVEN West Ham Champions

EIGHT Death and Goals

NINE Puddy

TEN Peace in Our Time?

ELEVEN Transformation

APPENDIX 1 West Ham United in the First World War

APPENDIX 2 Wartime Champions 1915–1919

APPENDIX 3 Wartime Leagues (Outside London)

APPENDIX 4 West Ham’s Wartime Players

Bibliography

Copyright

PREFACE

I am very pleased to have been asked by Brian Belton to supply a short preface for this interesting and compelling book. It’s difficult to imagine many more emotive subjects than football and war. Any West Ham supporter like me will be fascinated by this book which describes a very special part of the club’s history in the early twentieth century. It’s a unique story, a period when the club, players, officials, supporters and a nation went through extraordinary times and did extraordinary things in the service of country.

The First World War centenary makes many people remember, like I do, the terrible carnage of the Great War and the loss of so many young men from one generation. This is a tribute to the role West Ham United played in that conflict, something which is not widely known.

The chapters of the book, with titles like ‘The First Thunder’, ‘Football Goes to War’ and ‘Death and Goals’, tell a compelling story. I am sure every reader will be moved, which is very timely as we remember those who gave their lives for us.

Jim Fitzpatrick

MP for Poplar and Limehouse

2014

FOREWORD

‘WAR HAMMERS’ – THE HISTORY OF WEST HAM UNITED IN THE FIRST WORLD WAR

I have been a lifelong supporter of West Ham United and, having as a boy lived directly opposite the Boleyn Ground, that place and the club have been a constant in my life; somewhere I came from and of course a location I have returned to. As such, like many fans, West Ham is part of who I am, but at the same time the club is made of part of me. This is what being a supporter is about, and that is what I am first and foremost in terms of my relationship with the club.

I was born just eighteen years after the First World War and, as such, three years before the Second World War. The Great War was still very much part of people’s consciousness. In many ways, as Brian Belton, another committed Irons fan, illustrates in this book, West Ham United and the surrounding communities, were shaped by the events and circumstances of the years between 1914 and 1918. Even a century later, the area and the club continue carrying the culture that was formed during those years of conflict. This includes a sense of place and the character of the area (somewhere between ‘attack’ and ‘never give up’).

The years of the First World War saw West Ham United start a rise that saw it become a modern football club. The organisation was obliged to definitely pull away from its paternalistic roots, to become consciously part of a new pioneering form business venture, based on a sporting/leisure model. This laid the foundations of a club that, when the conflict was done, was able to firstly push its way into the Football League and then, just five years on from the war, find its way, on merit, to the first Wembley Cup Final. Here the Hammers not only challenged and almost matched the might of the northern monopoly of football (in the shape of Bolton Wanderers) but on any other day, given better circumstances (as Brian’s Lads of ’23 suggests) would probably have beaten the Trotters.

This was a phenomenal, meteoric rise, but its foundations were forged out of the years of conflict and hardship that are chronicled in the pages that follow. Now, as the time comes for us to leave Green Street, everyone connected with the club faces another giant leap. As is often the case, the past gives us an insight into the future and shows us there is time for change, and change usually happens according to what the times dictate.

In War Hammers Brian has brought to life the fascinating and entertaining journey West Ham made during an era demanding tremendous innovation and dedication on the part of players, management and supporters. This is an interesting, fascinating and sometimes funny story of excitement, glory, disappointment and loyalty that will cause the reader to smile, reminisce, laugh and occasionally shed a tear as they relive the spirit and life of one of the most iconic football clubs in the annals of the game. The wit and insight of those connected with the club is mixed with expressions of frustration, delight, pain, elation and adulation. It is a story of ‘us’ and ‘them’, a fight against the odds but also finding, living and moving on; to that extent Brian has written a biography of West Ham during the most demanding of times for the club, but it is also a story that looks forward as well as back. This reflects the character of football; we must honour the past, for that is what we are and where we come from, but we have a duty to provide a legacy for the future: the place we are going to. Sadly, some great club names from the history of our game have perhaps concentrated too much on the former and not enough on the latter. We must not make that mistake.

When West Ham United left the Memorial Ground, many saw it as the end of the club. But from 1904 onwards, the Hammers moved forward and of course grew to be the team we know today: a major force not only in football, but an influential organisation in sport and the East London/West Essex area that surrounds the club.

As we look towards Stratford, post the 2012 Olympic Games, although it seems there are echoes of the type of pessimism that surrounded West Ham United as the clouds of war gathered in 1914, I believe that the club’s move to the Olympic Stadium will be the start of a similar era of development and growth. Just as back when the twentieth century was young, those who ran and organised the club understood that it needed to make the most of the times and adapt given every opportunity. In the early years of the twenty-first century, the Hammers, having come of age at the Boleyn Ground, need to move on if the club is to make its place at the next level of development and become a significant national, European and world footballing power.

War Hammers is a story of simple passion and a place that has given rise to its own multifaceted universe of hope, skill and endeavour – the words from such a realm will always reward the reader – but we, the stewards of the present, have an obligation to take all that desire and enterprise on into yet another century. If we were to fail in this task we will have let down not only ourselves and those we will pass our club on to, but also the people who gave their all to keep the Hammers alive during the dark days of war. They effectively did what they did for us, so that we might benefit, by way of the joys, solidarity and challenges we have known under the banner of the crossed irons.

Over the next few years we can, in return, give them (ourselves and those who come after us) a home, a home where we can grow and become all we can be – a home we, the fans of the future and those who went before, deserve. A home for the Hammers – all the Hammers!

I think you will agree, as you read this book, that the people Brian brings back to life deserve this and would want us to do all we can to ensure the claret and blue heritage and future existence of what they bequeathed to us.

David Gold

2014

INTRODUCTION

This book is about war and football. It charts a relationship between these two human pursuits through the life of one particular team, West Ham United, in the dark, grim seasons that were played out from 1913/14 to 1918/19. But, as is the way of all text, there was a path to the writing of the words that follow.

What I have written in these pages was inspired when, years ago now, roaming along an isolated and exposed headland, overlooking the Gulf of Genoa, in Italy, I was amazed to come across a weathered monument to Private Arthur Ley Davies, a casualty of the First World War, recruited to the service of King and Country as a West Ham ‘Pal’.

I had known about the 13th (Service) Battalion (West Ham Pals) and, as part of the Essex Regiment, their heroics in France during the First World War for most of my life. The original West Ham Pals got their moniker from being made up of mostly West Ham United fans; their battle cry ‘Up the Irons!’ recalled West Ham’s original nickname before they became known as the Hammers.

On my return to London I began to find out about Arthur Davies. I discovered that he was born in Saffron Walden – at the time of his birth a relatively remote place in the heart of the Essex countryside. The Davies family relocated to Forest Gate in 1910, to No. 110 Studley Road. Five years later, in a Stratford (E15) January, the young Davies enlisted to defend the Empire.

My research continued and took me across Europe and back in time to the throes of the First World War, but at the same time I was returned to the heartlands where I was born, and Arthur and his family lived. This journey caused me to develop a picture of a ‘football time’ and a football team within that time, the club with which the West Ham Pals and I share an allegiance. This adherence is the reason why, whenever I have been a long way from east London, sheltering from cold Antarctic winds in the Falkland Islands, sweltering in Hong Kong afternoons or long, lonely African nights, on hearing or reading news of ‘my’ West Ham, I have whispered to myself ‘Up the Irons!’

A GENERATIONAL THING

Most commentaries on the history of football, especially those going back more than fifty years, are written on the basis of secondary sources; that is, they bring together what other people have written before them. When looking at events of the First World War it would be impractical not to do this to some extent, but the foundation of this book is somewhat different. In terms of gaining primary material I am indebted to Eddie Lamb and Dennis Parker, two great, authentic custodians of the history of West Ham United in the noble tradition of amateur chroniclers, unsullied by commercial limitations. The journal Soccer History and John Bailey’s work on football in the First World War have been great sources of relevant literature. However, I have also called on memories and interactions with my family and community over something close to half a century that have taken me (and now hopefully you) back to a time when West Ham United were still an adolescent organisation, a mere thirteen years of age.

My family have lived in the east London area, from where the Hammers have traditionally drawn support and players, since well before even the coming of Thames Ironworks, the shipbuilding company that gave birth to West Ham United. It is hard for those who are not familiar with the days when the ’Ammers were young to understand the impact that the football club has had on the area in which it has developed. It was, as it still is, a central focus for sport and the sportsmen of the Docklands. The club grew into one of the most important cultural influences in the East End of London and one of the largest businesses in the district. On match days the club directly and indirectly employed hundreds, maybe thousands of people, most on a casual, part-time basis. One was my paternal grandfather, Jim Belton, who worked on the turnstiles but was also involved in the maintenance of the Boleyn Ground from time to time. Like his full-time job, as a stoker in Beckton Gas Works, he had inherited these roles from his father (William). The Hills family, who had founded Thames Ironworks, had been amongst the founders of gas production and supply in London, and the links between the gas works and the football club remained strong until after the Second World War.

William Belton had been a fine sprinter and, supported by his trainer/manager Tony ‘Two Hats’ Falco, had competed on the professional circuits all over Britain. Bill – who had faced, beaten and trained with Charlie Paynter, the West Ham trainer to be, at West Ham’s first home, the Memorial Ground (which was also an athletics and cycling venue) – was later employed in France to train with the fine Swiss middle-distance runners Paul Martin and Willy Scharer in their preparation for the 1924 Paris Olympics. The Americans, Jackson Scholz, Charles Paddock and Horatio Fitch, saw the positive effect of Bill’s professional knowledge and took him on for a number of sessions. All this was a very risky business for the athletes. Although most of the top runners were taking ‘unofficial’ coaching at the time, it was strictly against the amateur code. If the Games’ administrators had found out that any athlete had trained with a professional it would almost certainly have meant expulsion from the Olympics and probably from the amateur ranks. However, Bill’s services were dispensed with as Scholz (the Mississippi Canon Ball) felt that constantly being beaten by the little cockney was doing his morale no good.

Bill’s sons, William Junior, John, Bronco and Jim (my grandfather), were all high achievers in sporting fields. Bill was a good amateur footballer who raced pigeons and whippets, and John, who was a Thames bargeman, competed in a number of sailing classes. Bronco was a boxer and wrestler of some renown, whilst my granddad would compete at anything for money, from prize fighting to lifting weights. All had, at some point, contact with Paynter and West Ham trainers Abe Norris, Frank Piercy, Jack Ratcliffe and Bill Johnson, both through sporting activities and association with the club. However, many of the West Ham professionals either took part in or were spectators of the proud sporting traditions of the West Ham area. Danny Shea and George Hilsdon liked a flutter on whippets and pigeon racing, and both also watched local athletics form. Syd Puddefoot took a great interest in sport in general, whilst Billy Cope, George Kay and Alf Leafe were amongst the many Hammers who competed in athletic events. Of course, being young men, the West Ham players would watch and wager on the prize fights that took place on summer weekends and bank holidays.

Another great-grandfather (my paternal grandmother’s dad), Jimmy Stone, was a gypsy bare-knuckle fighter. He had acted as a sparring partner for a number of fighters trained by Tom Robinson, who had been a coach with Thames Ironworks and went on to serve the young West Ham United in the same capacity. His brother, my great-uncle, had played for Djurgardens IF, the Swedish soccer champions of 1920, who the wartime Hammer Jack Macconarchie had turned out for and coached in 1921. He was working for the Fenerbahce in the early 1930s at the time when West Ham legend Syd Puddefoot came to the great Turkish club.

It is the stories of these interactions – from my great-grandparents, my grandparents, great uncles and aunts, and reminiscences from my mum and dad and their siblings about what these people had to say – together with long conversations with close to 100 former players, some of whom, like Ernie Gregory and Eddie Chapman, had served and been around West Ham United for most of its history, as well as responses from contacts all over the world, that are the bedrock of this book. The perspective has been built from the earliest days of my own half-century of life. The first time I wrote any of it down was in June 1962.This produced seas of notes, jotted down in schoolbooks, on odd bits of paper and cigarette packets – there were even a few scribbled words on the back of a bus ticket reflecting an ‘interview’ with West Ham’s former manager and player Ted Fenton on the top deck of a number 15 bus. It took place in the mid-1960s; the tragedy is I just can’t read it and have little recollection of what was said, although I can recall him saying that Andy Malcolm had been one of the ‘bleedin’ best defenders in the world’ and that ‘he’d have knocked spots off Pele’.

Through structured research of the history of West Ham United from the team’s social and political origins in the nineteenth century up to the period that this book deals with, combining both primary and secondary sources, it is clear that during the First World War there was another war going on within football itself. In the first part of the twentieth century the game, at its professional grass-roots level, had been wrestled from the control of the British ruling class. The social and psychological effects of this on the male-dominated elite groups of the time were probably much more complex than the practical implications. Although association football was still administered by the old-boy network – its bureaucratic and regulatory centre being dominated by Oxbridge graduates representing the nation’s establishment – the supporters, the professional playing force and many of the club staff, and even board members, were overwhelmingly people from working-class backgrounds. This had happened despite the constant efforts of the financial and social elite to hold on to the power embodied in what had become the game of the masses. The symbolic relevance of this should not be underestimated; it stood as an example of the ‘have nots’ appropriating the power and influence of the ‘haves’.

As such, when the First World War caused former supporters to enlist and/or reassess their life priorities in response to the demands of war labour, and the great professional clubs saw attendances plummet, those who had initiated and moulded the game for the development of ‘Manly honour’ and ‘Muscular Christianity’ and attempted to use it for the ‘betterment’ of the ‘worthy poor’ (as a means to promote the ideals and personality traits congruent to the service of Empire) seized the moment. Church, press and parliament conspired to bring an end to professionalism, which in effect would have meant the abolition of the clubs that enabled the same. Of course, the clubs fought back with all the resources they could muster: the friendly press and the game’s entrepreneurs, such as West Ham’s William White. With footballing generals like the Hammers’ manager Syd King and his right-hand man Charlie Paynter, professional football laboured long and hard to maintain the integrity of the club system by providing the means to finance the maintenance of grounds, stadiums and the very fabric of the professional game. The London Combination tournament was one of many tangible manifestations of football’s ‘class resistance’ as was West Ham United’s energetic and successful contribution to that competition throughout the years of the First World War.

This conflict needs to be viewed in the context of the early years of the twentieth century, a time of paranoia amongst those who had traditionally ruled Britain. Fifth columnists, foreign nationalism, Unionism and, of course, with the removal of the Tsar in Russia in 1917, Communism, were all seen to be waiting to exploit the cracks in capitalism that had been fully exposed by the war. Any mass gathering of the working class merely provoked panic amongst those with much to lose. One of the most profound anxieties connected with soccer was that professional footballers would unionise. This was not grounded in trepidation that players might take independent industrial action, as this could be handled. The dread was that a football union might support wider industrial action, so bringing worker/employer disputes into the mass public consciousness, promoting the escalation of industrial action via example, and in the process harnessing forces of local and national solidarity embodied in the support of the professional game. This scenario was the product of low-level hysteria and, as we shall see, was in fact responsible for those who had traditionally been the controllers of football taking their eye off the ball and thus clearing the way for commercialism to take a firm grasp on the professional game.

As such, class anxiety was the kernel of the football war within the First World War and therefore no history of the game in this period is complete without taking this force into consideration. Make no mistake, the First World War was used as an opportunity to advance class interests. With regard to football, this was in essence an exercise in blatant propaganda and subtle indoctrination and, this being the case, anything but moral. The hundreds of thousands of working-class men who perished on the battlefields of Europe – one of whom was ‘Gypsy Boy’ Jimmy Stone – in the cause of an Empire which kept them poor, were used to inspire guilt in an attempt to undermine and destroy an institution, and a means of cultural and social expression, that many of those who had died helped to win and develop.

This book is a homage to those men but it also seeks to expose part of the truth of how the control of the game changed hands. From the time of its first organisation it was a bastion of the aristocratic class. There followed a short period when association football was truly the working man’s resource, used to gain time off from work and as a form of leisure, recreation and means to socialise. Thereafter, starting in earnest in the years following the First World War, the ownership of soccer was increasingly taken over by the ethos of commerce; at first this was represented by ‘local men made good’, the owners of small to medium-sized businesses, but the seed grew. Today the English game is, in effect, in the hands of Roman Abramovich – an utterly ruthless capitalist, who made his billions on the back of impoverished millions of his own countrymen. He is the new Tsar, the Kaiser of football, ruling the game from the club that Hammers like George Hilsdon and later Len Goulden helped create and nurture.

This is why the history of football in the First World War is important. It helps us, those who give up time and money to support the game, to understand what is happening today. It seems, at least as far as football is concerned, that it was not Germany and the Central Powers who lost the war, or Britain and her allies that won it; as far as the ‘beautiful game’ is concerned, it appears that the war to end all wars planted the germ for the new Roman Empire, cheered on by Chelsea supporters, wearing the inane smiles of the historically uninformed under Cossack hats, paying more for a season ticket than a West Ham Pal would have taken in his soldier’s pay for the entire duration of the First World War. Of course, very few of those East End and Essex boys would have survived that long. I hope the pages that follow will in some way celebrate them and win back just a little of the spirit of football they once carried – to that extent it echoes their battle cry, ‘Up the Irons!’

Brian Belton,

August 2007

ONE

THE FIRST THUNDER

As professional football players reported back for training in mid-August 1914, fighting had been going on for about four weeks and by the time the season kicked off, the British Expeditionary Force had crossed the channel and were desperately, alongside the French, trying to resist the German invasion descending from Belgium.

Resolute but almost totally unprepared, the British professional army was not, at the start of the war, well equipped. At the same time, as a volunteer army, in terms of numbers it was minute relative to the conscript-rich standing armies of Europe. Great Britain had an army of only 450,000: this included a pitiful 900 trained staff officers (approximately) and about 250,000 reservists. In contrast, Germany was recognised as having the most efficient army in the world. Its structure included universal mass conscription for short-term military service followed by a longer period in reserve. The German Army placed great emphasis on high-quality training and maintaining a large number of experienced senior officers. In 1914 it comprised twenty-five corps (700,000 men). There were eight army commands and a further ten were created during the war. A cavalry regiment and other support forces were attached to each two divisions. Within a week of war being declared, the reserves had been called up and some 3.8 million men were in the German Army. By August 1916, about 2.85 million soldiers were serving on the Western Front with another 1.7 million on the Eastern Front. As such, it is understandable that Kaiser Wilhelm II referred to the British forces as ‘Britain’s contemptible little army’. The name stuck and the survivors were forever to be known as ‘The Old Contemptibles’. However, the sheer lack of numbers was a problem for those responsible for the defence of the realm. While many thought the war would be short-lived, and ‘over by Christmas’, Lord Kitchener, the newly appointed Secretary of State for War, was not so confident. He let the government know that in his bleak opinion the conflict would be determined by the last million men that Britain could commit.

The scale of the First World War placed a huge burden on the small British Army, but the military and social values of the time shied away from the introduction of conscription. With a ‘call-up’ politically unpalatable, Kitchener decided to raise a new army of volunteers. On 6 August, Parliament sanctioned an increase in army strength of 500,000 men. Just days later, Kitchener made his first call to arms, asking for 100,000 volunteers to come forward. It was stipulated that those who ‘took the King’s shilling’ should be aged between 19 and 30, at least 5ft 3in (1.6m) tall and with a chest size greater than 34in (86cm).

The war did not go well for the Allies in its earliest stages. The well-prepared German Army, working to an impressively defined and executed strategic plan, swept into Belgium and France, pushing back the Allied forces and taking prisoners. On 20 August they crossed the River Meuse and captured the town of Lille, just over the French border. The French and British, still hastily trying to work out a co-ordinated plan, were taken by surprise by the force and nature of the German assault, but the courage and tenacity of the Allied troops managed to check the enemy advance and the conflict ground into a near impasse of continuing carnage. In September, following the Battle of the Marne, the German Army and the British Expeditionary Force dug themselves into the first trenches of the war. The formation of the Western Front, running from Switzerland to the coast, bogged down British hopes of an early victory in a sea of mud and established the character of the war for the next four years.

NOT OVER BY CHRISTMAS

At the start of the First World War no one thought that the fighting would go on for years, but as it became clear that the conflict was going to be protracted many thought that football had a part to play in helping to maintain the morale in the trenches. The game also provided some semblance of normality at home and, as time went on, like most sporting and entertainment organisations, West Ham United took a role in providing those still at home (and the men in the forces who picked up news of the game) with something to take their minds off the boredom, misery and butchery of war. At the same time, the large crowds attracted by matches were seen to offer an ideal opportunity to stage recruitment drives.

SILENT NIGHT, HEILIGE NACHT

The compulsion and possibilities of football were exemplified with the birth of the now well-known legend of an event that was said to have taken place on the Western Front on Christmas Day 1914. The one-time fable goes that the British and German armies, having little stomach for the fight over the season of goodwill, called an impromptu and unofficial halt to attrition. A ball appeared and a game took place; mutual enemies became temporary comrades in sport. The ‘truce’ spread along the length of the front, and soldiers exchanged simple gifts and heartfelt embraces.

In the last few years the former myth has been underwritten by historical research (see for example Silent Night: The Story of the World War I Christmas Truce by Stanley Weintraub; Jim Murphy’s Truce: The Day Soldiers Stopped Fighting, Meetings on No-Man’s Land by Marc Ferro, Malcolm Brown, Remy Cazals, Olaf Mueller and Helen McPhail; and Christmas Truce: The Western Front December 1914 by Malcolm Brown and Shirley Seaton) and it seems there might have been any number of incidents like this during the conflict. Indeed, my great-grandfather told how he had been part of such a game. However, the stories have gelled and fused in that historical place somewhere between fact, fiction, allegory and parable, while history tends to relate what people are prepared to believe rather than what actually happened – to that extent we make our own history. But it is as sure as can be that the East Surrey Regiment kicked two footballs ahead when charging the enemy at Calmaison and, as a Yorkshire corps went over the top to face a bayonet charge, one of their number shouted, ‘Come on lads, let’s do this for the Wednesday’, and the West Ham Pals faced death with a cry of, ‘Up the Irons!’ These are examples of the potential of the game: the solidarity it engenders and the passions it provokes. This being the case, the author chooses to believe that if football can inspire men in this way as they face their own mortality, then the same zeal and similar accord did indeed cause foes to be friends that Christmas (and probably others).

THE MIGHTY BURGE

Surprisingly, not all footballers were fit for the army. Bill (Walter) Masterman, a goalscorer for Sheffield United in the 1915 FA Cup final who turned out for West Ham the following season, was rejected for military service because he was deaf. Others, including East Ender Syd Puddefoot, worked long, exhausting and often dangerous shifts in munitions factories.

Just one example of what players were obliged to put up with came in November 1915. A Bromley amateur, Pomeroy Burge, made an eventful appearance for West Ham at Stamford Bridge. He scored once and missed two other chances at crucial times as West Ham went down 5–2. Before the game he had been on the night shift at the Woolwich Arsenal, and straight after the final whistle he hurried off to begin another. He was back at the Boleyn Ground the next day for training, beating the rest of the squad in a twenty-five-lap race around the pitch! When asked about his durability he put it down to drinking around twenty pints of stout each day (starting with a couple for breakfast!), minimal food intake (usually restricting himself to a tin of Lyles Golden Syrup and a bun purchased from Jackson’s bakery in the Barking Road) together with often spending his hours of sleep stretched out, shirtless, on the marble counter of his brother-in-law’s fishmongers in East Ham, regardless of season or temperature. It was rumoured that Burge volunteered for army service and in the course of his duties made a single-handed attack on a German trench. Emptying his rifle he fought his way up the enemy line with his bayonet until it broke inside the body of one rather portly foe, whereupon he happened on a plank of wood with a nail in the end which he used to finally clear the trench of the enemy. It seems he would have been awarded a medal, but when his commanding officer found him sitting in the captured German mess guzzling ‘liberated’ schnapps (actually finishing off the last of several bottles he had found) his chance of becoming an official hero evaporated in the threat of being charged with disorderly conduct (it was rumoured Burge told his rather posh superior where he could shove his mention in dispatches).

THE LAST SOUTHERN LEAGUE SEASON

West Ham United opened their 1914/15 season with a home fixture against Gillingham in front of 5,000 paying customers, many of them looking to the Irons to help them take their mind off the tension of war. Percy L. Wright had turned out for the Hammers that day. Born in Darley Dale, Percy had played for Heanor Town before moving to Wednesday, and between 1910 and 1913 played 20 games and scored 6 goals for the Sheffield club. He made just 10 appearances for the Hammers in 1914/15. The outside left scored his only goal of that term in a 4–1 win over Bristol Rovers at Upton Park. His brother James was born in Hyde, Cheshire, and the two Wright boys moved to the USA in the summer of 1919 and for a time played semi-professional soccer there before moving into baseball. James became known in that sport as Jim ‘Jiggs’ Wright and by 1927 was good enough to play a season for the St Louis Browns. The baseball archives detail Wright the younger as being born in September 1900. Jim Wright passed away on 10 April 1963 in Oakland California.

Harold Caton was brought back into the side for that game against the Gills in the number 11 slot. He had joined the club in 1912 but had not been able to make himself a regular in the first team.

Another debutant for the first game of the new season was Blackburn-born George Speak. First seeing the light of day on 7 November 1880, he played 13 times over the first two wartime seasons. As was the case with many Hammers, Speak, a thickset left-back, came to the Boleyn Ground from Midland League Gainsborough Trinity. He had begun his footballing career in his native Lancashire with Clitheroe Central and Darwen. After a trial for Liverpool in 1910, George joined West Bromwich Albion and then Grimsby Town, but between 1910 and 1912 he made only 4 Football League appearances for the Mariners before taking the short trip across Lincolnshire to Trinity in July 1913. Speak spent ten months with Gainsborough before being transferred to West Ham in May 1914. He started the 1914/15 term as the Iron’s first-choice left-back, but he lost his place after four matches and did not regain it until the end of March.

Gillingham began the 1914/15 Southern League season with what had become their usual unsuccessful visit to Upton Park (they lost 2–1). In 15 attempts, the Kent side had only recorded victories twice at the Boleyn Ground, in 1907/08 and 1908/09. However, the Hammers, along with the rest of football, stumbled into the 1914/15 season, reacting day to day to the situation they found themselves in. One of the first things the club did was to coordinate contributions from its players to the War Fund. This was publicised as much as possible, giving a loud and clear message, ‘We know we are at war!’ Syd King reminded the press that the club was going to add £60 from a practice match to the players’ donation. In those days it wasn’t unusual for people to turn up and pay to watch such events, much like they might for a friendly now.

In the 1913/14 campaign the Hammers had let in far too many goals for King’s satisfaction. As such, the keepers from the previous term were out of favour: Tom Lonsdale disappeared from first-team reckoning, whilst Joe Hughes would have to wait until December before getting another chance. Joe, a Londoner born in 1892, began his football career with Tufnell Park and then South Weald, from where the Hammers signed him in 1911. After making 90 League and 15 cup appearances for West Ham, Joe was transferred to Chelsea in 1919. He would appear for the Pensioners and West Ham during the First World War.

The West Ham custodian for the first part of the 1914/15 term was Nottingham-born Joe Webster. Joe would see three years’ active service in France during the First World War and played with the ‘Footballers Battalion’ (a fighting force put together in a similar way to the West Ham Pals, but made up of talented players). He had started his life between the posts with his local club Ilkeston United and had joined West Ham from Watford in 1914. He played in the first 17 of West Ham’s 1914/15 fixtures, but would be associated with the Hammers after the First World War, playing 2 Second Division games for the Irons, deputising for Ted Hufton against Huddersfield Town and Port Vale at Upton Park in the 1919/20 season. Joe, who played twice for the Southern League, was 31 in 1914.

The opening day of the season was also the Upton Park baptism of full-back Bill Cope, who King had brought to West Ham after 5 seasons, 62 appearances and 1 goal for Oldham. Originally hailing from Stoke-on-Trent, Staffs, on 25 November 1914 Bill would hit ‘the big three zero’. Cope was an exceptionally hard defender, able to play at right- or left-back and inclined to be a bit forthright in the challenge in compensation for his relative lack of pace.

Another summer import, this time from Hull City, was the lively left half Austin Randolph Fenwick. Born in Hamsterley, County Durham on 26 March 1881, Alf (as he was known) began his life in the game with Cragheart United in Co. Durham. He progressed to Football League status with Hull, making 17 appearances and scoring 7 times while taking over as centre forward following the transfer of the Yorkshire Tigers’ regular number 9, Tom Browell, to Everton.

As what was to be West Ham’s last Southern League season got under way, it became clear that Tom Randall’s time at Upton Park was over. The Hammers’ captain would never recover from the leg injury he had sustained the previous season. He took part in the win over Gillingham but the leg had not improved and in December, after just 5 appearances, his first-class football career was finished. He had been a regular in the Southern League at left half and had been honoured with the captaincy of the Southern League Representative XI. He turned out for the Southern League on five occasions in games against the English, Scottish and Irish Leagues in 1912, and the English and Irish again the following year. Randall was also selected for a Football Association XI. Tom retired having made 205 appearances for the Irons and scored 9 goals. He passed away in 1946.

Randall was eventually succeeded as a regular in the first team by Jack Tresadern, but for much of the 1914/15 season Danny Woodards swapped the number 6 shirt for the number 4 position. Dan was still on the staff at the club when the Hammers were elected to the Football League in 1919, having played 180 games for the Boleyn Boys (including wartime appearances) and continued to play for and coach the reserves.

The shifting of Woodards allowed Bob Whiteman an extended run in the Southern League side. After appearing for Manor Park Albion (near neighbours of the Irons) like his Hammers contemporary George Wagstaff, Bob had plied his trade with South Weald and Norwich City, but was by far the most successful of several signings made by the Irons from the Norfolk club. He turned out 34 times for the Hammers as the clouds of war gathered over Europe.

LUMPING LUTON

Gillingham gained vengeance and more when West Ham made the trip to Kent later on in September, but the Hammers seemed to have recovered their poise three days later, beating Luton 3–0 in front of 5,000