Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

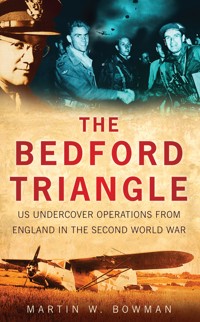

The Bedford Triangle portrays the crucial part played by the British Special Operations Executive (SOE),US Army Air Force (USAAF) and American Office of Strategic Services (OSS) in operations behind enemy lines in occupied Europe during World War Two. Milton Ernest Hall, a country house in Bedfordshire used officially as the UK headquarters of the US Army Airforce Service Command, was located at the heart of a network of top secret Allied Radio and propaganda transmitting stations, political warfare units and undercover British and American formations dealing in espionage and subterfuge. Martin Bowman draws upon revealing first-hand accounts, together with official documentary evidence, to provide tantalising glimpses of the cloak and dagger operations. The author's extensive research has revealed that Allied Secret Service organisations participated in even more unorthodox activities, such as clandestine propaganda and political warfare. He also reveals the truth behind what really happened to legendary band leader Glenn Miller.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 455

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

THE BEDFORD TRIANGLE

‘The first casualty when war comes is truth.’

Hiram Johnson US Senate, 1917

THE BEDFORD TRIANGLE

US UNDERCOVER OPERATIONS FROM ENGLAND IN THE SECOND WORLD WAR

MARTIN W. BOWMAN

First published in 1989 by Patrick Stephens Ltd

First published by Sutton Publishing Limited in 1996

This edition first published in 2009

Reprinted 2013

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2016

All rights reserved

© Martin W. Bowman, 1989, 1996, 2003, 2009

The right of Martin W. Bowman to be identified as the Authors of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7509 7974 0

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

Preface to New, Revised Edition

Introduction

Prologue: Douglas D. Walker

1 The Carpetbagger Project

2 Area of Doubt

3 Circle of Deception

4 Jedburghs and ‘Joes’

5 Black Sheep in Wolves’ Clothing

6 Fateful May Day

7 New Blood

8 The Belgian Connection

9 New Methods

10 French Escapade

11 Fresh Fields

12 Final Days at Harrington

13 Spring will be a Little Late this Year

14 The German Connection

15 Glenn Miller: ‘Missing, Presumed Murdered?’

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Many people helped in the preparation of this book, none more so than Connie Richards, a Bedford lady who has been researching the intriguing Miller mystery for many years, and who, along with her husband, Gordon, very kindly allowed me to use their home on several occasions as a base for operations. I am also especially indebted to Carl Bartram and many other researchers, contributors, veterans and fellow authors, some of whom very graciously allowed excerpts of their work to be used in this book. Mike Bailey was his customary altruistic self, permitting me to borrow publications and research material to fill in the gaps I could not, alone, fill. I would also especially like to thank the late Dennis Cottam, a life-long researcher into the Miller legend, for allowing me to quote parts from his extensive library of tapes and interviews. This book would be the poorer without them.

Obtaining photos of the top secret Carpetbagger group did not pose a problem because of the generosity of its members, in particular Sebastian Corriere, who started the ball rolling by providing me with a wealth of material, written and photographic. I am also most grateful to ‘Rudy’ Rudolph, Wilmer Stapel, Colonel Robert J. Fish (USAF Retd) for their immense contribution of photos and to the late Douglas Walker, who despite the incessant organizational demands of the Carpetbagger reunion, always found time to unearth more material and answer my individual questions.

I am no less grateful to:

John Bailey; Joseph Bodenhamer; Warren Borges; Thompson H. Boyd; William J. Carey (USAF Retd); Art Carnot; Elmer ‘Bill’ Clarey; Forrest S. Clark; Ron Clarke; Lester Cowling; the late Arthur Davies; Bill Dillon; Colonel Peter D. Dustman (USAF Retd); Professor Marcial and Mrs M. Louisa de Echenique; Roy Ellis-Brown; Don Fairbanks; Brigadier-General Richard E. Fisher (USAF Retd); Royal D. Frey; Peter Frost; Michael L. Gibson; Ken Godfrey; Gene Goodbread; Chris Gotts; Paul E. Gourd; John W. Guthrie; Cliff and Wendy Hall; Lady Hastings; Mrs Edmund Walton Hill; Harry Holmes; Julius M. Klinkbeil; George T. Johnson; Dave Mayor; Roxanne M. Merritt, Curator, JFK Special Warfare Museum; Frank McDonald; the late William Miskho; Wiley Noble; Erwin Norwood, Lieutenant-Colonel (USAF Retd); John Page; André Pequet; the late Louis Pennow; Nick Pratt; John Reitmeier; Ivon Ressler; Denny Scanlon; Rodman St. Clair; Joseph Staelens; the late Victor Stilwell; Art Talbot; Bernard Tebbutt, Carpetbagger Museum, Harrington; Dale Titler; the late Edgar Townsend; Graham Truscott; Edward J. Twohig; Captain Barney Welch (USAF) and Maurice Whittle.

All of the above, whether they be former Carpetbaggers or English contributors, came forward with rare and exciting photographic material previously tucked away in the recesses of their albums and attic chests. I am most grateful to them all and to the other contributors for their hand of friendship.

PREFACE TO NEW, REVISED EDITION

In 1989, when this book was first published, many files, particularly those concerned with the OSS, political warfare operations, and SOE agent-dropping missions, remained closed. Many files in Britain are still sealed from public view but others, particularly those in the USA concerning Office of Strategic Services (OSS) operations, have been opened thanks to the US Freedom of Information Act. They give the background to some of the Carpetbagger missions which were described in the first edition. I am indebted to Carl Bartram, an OSS researcher in Wellingborough, for kindly making me aware of this new material, and for his help in tracing former members and providing photos, many of which are published here for the first time. Carl’s diligent research and correspondence with OSS personnel has led to his appointment as their official UK contact, and in 1995 he hosted the very successful fiftieth anniversary OSS reunion in Northamptonshire. One result was that Carpetbagger and OSS personnel were able to compare notes on their joint operations during the clandestine war, 1942–5. Thanks to Noel Chaffey, the part played by the RAF in Carpetbagger operations from Harrington is revealed publicly for the first time.

During the Second World War at least sixty-one ‘safe houses’ were used for agent operations, and there were probably more. Many were located in the immediate vicinity of Harrington and Tempsford. Several, like Holmewood Hall, Gaynes Hall, Farm Hall, Sunnyside House and Brock Hall, were used as holding areas for Special Operations Executive (SOE) and OSS agents. The grounds of some of them were used for storage and training, while the real nature of operations at Finedon Hall can now be revealed. Now, all of these country houses have been added to the ‘Triangle’. Some were known as Area ‘E’, Area ‘H’ and Area ‘O’, and they were used for American covert operations. Others, like Area ‘B’, were actually located in the USA, so where were Areas ‘A’, ‘C’, ‘D’, ‘G’, and possibly others, based? It begs the question: was Milton Ernest Hall one of these? What really did go on there and was it connected with the OSS, SOE, Political Warfare Executive (PWE) and codebreaking operations in the Bedford Triangle? The answers to these questions might eventually solve the Glenn Miller mystery too.

In 1992 files released gave details of monitoring operations in 1945 at Farm Hall when ten members of Germany’s ‘Uranium Club’ were ‘guests’ there. I am most grateful to Professor Marcial and his wife, Mme Louisa de Echenique, for their hospitality and valuable assistance with source material concerning this period in the long history of Farm Hall. Several books published since contain transcripts of the secretly taped Farm Hall recordings, and their nuclear secrets make intriguing reading.

All of these revelations here and elsewhere reinforce the original premise put forward in the first edition of The Bedford Triangle that the close proximity of Allied intelligence gathering, political warfare and covert operations concentrated in one area was certainly not coincidental. Hopefully, now that the ‘Triangle’ has given up a few more of its sinister secrets, a clearer picture of these secret wartime operations has emerged. Undoubtedly, there are more to come. Whether we will be allowed to share in them is another matter.

INTRODUCTION

A dark limousine, its black shiny body and chromium bumpers gleaming in the faint July sunshine, motored along the meandering Bedford to Sharnbrook road on a quiet Sunday afternoon. Turning a bend the driver spotted two brick gateposts to reveal the entrance he was seeking. The car slowed and the chauffeur turned effortlessly into the narrow shingle drive. A few hundred yards further on there stood the baroque towers and solid walls of an imposing English stately home.

The official limousine picked up speed and motored sharply along the driveway, sending clouds of dust into the air and scattering a small fusillade of shingle over the well-manicured lawns. Onlookers could not see the car’s occupants. The windows were glazed over with specially darkened glass allowing those inside to see out but preventing any curious people from looking in.

Already, the strains of ‘In the Mood’ and ‘Chattanooga Choo Choo’ could be heard from around the back of the hall as the driver turned in to the inner courtyard at the rear. Carefully, he wheeled the car towards the old stables and slowed to a halt. At the double, two tall lean men in dark suits, wearing sunglasses, exited from the rear of the car, slammed the doors and took up position at the front of the vehicle. Quickly, and with only a sideways glance, they held open the right hand door. An unknown silver-grey-haired man emerged. He also sported sunglasses but was dressed in a light coloured suit. The aides ushered the old gentleman into the hall before anyone could get a good look at him.

Inside the hall itself the aides took up their positions as the elderly gentleman went upstairs to a room at the front of the hall where an open window overlooked the scene on the lawns below. It was certainly a sight to stir the blood. The musicians, all dressed in brown American Air Force uniforms with blue SHAEF patches on their shoulders, were waiting for the lead from their band leader, similarly attired but in the uniform of a USAAF major. He stood erect, trombone in hand, at the front of the bandstand. As if taking his cue from the latest arrival at the open window above, he struck up the ‘St Louis Blues’ march. The packed crowd around the lawns went into raptures. Some who left to answer the call of nature were surprised to be turned away from the hall by the men in suits and barred from going upstairs as they attempted to reach the rest rooms.

Everything had been done to re-create the atmosphere of the heady days of 1944 when Glenn Miller and his Army Air Force Band had temporarily been based at Milton Ernest Hall. He and the band had also used Twinwoods airfield nearby as a launching pad for their musical travels to almost all the heavy bomb groups and fighter squadrons stationed throughout war-torn England.

The band, the band leader and a local audience were gathered but an Englishman who had promised to attend was missing. He had good reason to attend this, the Glenn Miller anniversary concert at Milton Ernest Hall, on a normally peaceful Sunday afternoon in July 1980. During the war he had been batman to Glenn Miller when he had stayed at the hall.

The Glenn Miller orchestra was famous in pre-war America for its distinctive sound, arrived at by mixing some jazz, a large element of swing, and unabashed showmanship characterized by the flapping of their mutes, standing for solos and the choreographed pumping of trombone slides. Miller pursued musical supremacy, demanded perfection and drove his musicians hard. In March 1939 the band was contracted to play for the summer season at the celebrated Glen Island Casino in New Rochelle, New York. They broadcast from the Casino ten times a week, thousands of listeners tuned in and soon the band was a household name. One hit record after another followed, including Little Brown Jug, In the Mood, Chattanooga Choo Choo, Serenade in Blue, I Got a Gal in Kalamazoo and Moonlight Serenade, which became Miller’s theme song.

When the band went on the road, each live venue became a sellout. In Hershey, Pennsylvania, the band broke the attendance record set by the Guy Lombardo Orchestra eight years earlier and in Syracuse, New York, it played for the biggest dance audience ever. In December 1939 the band was hired for a three times weekly CBS national radio program sponsored by Chesterfield cigarettes. In the summer of 1940 the results of a poll made the Glenn Miller orchestra the top band in the country with almost double the number of votes of its nearest rival, Tommy Dorsey. Appearances in two Hollywood movies followed. In 1941 the Glenn Miller band featured in Sun Valley Serenade and a year later they appeared in Orchestra Wives.

By this time the United States was at war and the draft deprived Miller of most of his established musicians. At age thirty-eight Miller was spared the call up but if he enlisted he could perhaps help the war effort in a musical capacity, possibly by updating military music for the troops. Miller first offered his services to the US Navy, but was turned down so he tried the Army. On 12 August 1942 Miller wrote to Brigadier General Charles D. Young, outlining a desire to enable music to reach servicemen at home and overseas on a fairly regular basis. He argued that this would considerably ease some of the ‘difficulties of army life’. Miller’s desire to join the armed forces may not have been driven by patriotic reasons entirely. In August 1942 a strike by the musicians’ union against the record companies began and it was to last until September 1943, effectively keeping the bands out of the recording studios for a whole year. Although the record companies eventually capitulated, the strike was a severe blow for the Big Bands. Where once Benny Goodman was guaranteed $3,000 a night and Tommy Dorsey was getting $4,000, suddenly one night, the total take was just $700. A wartime 20 per cent amusement tax on nightclub receipts (which continued into peacetime) did not help. Tastes too began to change towards romantic singers who were much in demand for radio performances. In 1943 Frank Sinatra left the Tommy Dorsey band and other vocalists like Perry Como and Eddie Fisher followed. By the end of 1946 eight of the top US bands had disbanded.

Miller reported for induction on 7 October 1942. Eventually, he was named Director of Bands Training for the Army Air Forces Technical Training Command and authorized to organize a band at Yale University, which had become a training area for cadets. The outfit, officially known as the 418th Army Air Forces Band, was activated on 20 March 1943 with permanent station at Yale University.

Yale was not just a training area for cadets. It had links with counter-espionage going back to the days of the War of Independence when three members of the Culpeper spy ring, who graduated in the class of 1773, were established secretly by George Washington to gather intelligence on the British. Unlike the British, the US had no independent intelligence agency for most of its history. Spying was a rather informal affair, confined to the wartime military. With the outbreak of Second World War it became clear that the US needed a large-scale operation and quickly. What better place than academe? Especially since Yale was a hot bed of intrigue and unique secret societies such as the exclusive and infamous ‘Skull and Bones’ society, whose members are sworn to secrecy for life about the club’s activities. The society’s origins can be traced back to 1832, when William Russell founded it as retribution for a classmate’s having been passed over by Phi Beta Kappa. Many wealthy American families made their money trafficking in drugs. Yale’s secretive order of the Skull and Bones was involved in the opium trade and founding family were the Russells. Samuel Russell established Russell and Company in 1823 and acquired opium in Turkey, smuggled it into China and in 1830 established the Perkins Opium syndicate of Boston and Connecticut. During the Opium Wars Russell and Company was at times the only trading house operating in Canton and used the opportunity to develop strong commercial ties and handsome profits. The Skull and Bones cryptic iconography is derived from German University societies. Every year, each society taps a dozen juniors to join their upscale fraternity, where they recount their sexual histories, perform strange rituals, and prepare for a life among the ruling classes. Henry Lewis Stimson, President Theodore Roosevelt’s Secretary of War, and Averell Harriman, American Ambassador to Moscow were members.

The majority of leading agents in OSS (Office of Strategic Services), which was founded in 1942 for the acquisition and analysis of intelligence, were provided by Yale. Many of them including Henry Luce owner of Time-Life, and his wife Marjorie, Henry Stanley founder of Morgan Stanley, and Captain Charles Black (who later married Shirley Temple) were ‘bonesmen’ too. In fact so many ‘Yalies’ joined the OSS that the university’s drinking tune, the ‘Whiffenpoof Song’ became the secret organisation’s unofficial song. At the heart of OSS and home to most of Yale’s academics was the Research and Analysis branch (R&A) where social scientists, historians, linguists and even literary critics studied friends and enemies, real and potential, present and future. By the end of the war, R&A had gathered 3 million index cards, 300,000 photographs, a million maps, 350,000 foreign serials, 50,000 books, thousands of loose postcards – all indexed and cross-indexed, many of these gathered under the cover of the Yale library. Walter L. Pforzheimer, who helped found the CIA, was educated at Yale, arriving in 1931, then entered the army. Shortly after graduating from Officers Candidate School he was approached by a young officer who asked if he was interested in joining the intelligence community. ‘Beats digging ditches,’ he thought and became part of the OSS. He had two roles. One was as a liaison officer in the UK; the second was laundering money for the OSS. This was called the Yale Library Project and the money was supposedly being spent on the university’s collections. After the war he became the OSS’s Legislative Counsel for liaison with Congress and played a major part in writing the bill that brought the CIA into existence in 1947. His father made his fortune in oil but became a significant book collector. For Walter’s twenty-first birthday, he gave him a library. It was, said Walter, a shock that shaped his life. He went on to collate a huge selection of intelligence material. When he gave the works to Yale University in 2002, they included more than 15,000 books.

Apart from R&A, OSS comprised four other major categories: Secret Intelligence (SI) was responsible for intelligence gathering. Secret Operations (SO) parachuted agents into the occupied countries. Morale Operations (MO) was involved with propaganda broadcasts to the enemy to undermine his morale. X-2 the counter-intelligence service, which also handled the German Ultra intelligence deciphered at Bletchley Park in Bedfordshire, was dominated by Yale students and Yale alumni such as English Literature professor Norman Holmes Pearson while James Jesus Angleton went on to a legendary career as director of the CIA’s counterintelligence staff. Both belonged to the Skull and Bones. Myth says that the society’s members form a clique that rules the world. They have promoted one another in enormously successful political and business careers and presided over the creation of the atomic bomb, as well as the CIA. Even today, there is reportedly a ‘Bones club’ within the CIA, which helps promote the intelligence careers of members of the Yale secret society. A statue of Nathan Hale, which stands in front of the headquarters of the Central Intelligence Agency in Langley, Virginia, is a replica of one on the campus of Yale University.

On 28 July 1943 Glenn Miller’s new swinging military band made its debut in the Yale Bowl to a rapturous reception from the cadets. The Miller band continued to play at retreat parades and at review formations on the Yale Green, but really let their hair down performing at dances, open houses, parties and luncheons. On radio Miller’s musicians broadcast I Sustain the Wings, a series designed to boost Air Force recruitment. The band was such a hit and its appearances at bond drives so successful that Miller began to fear that they might be held stateside instead of being sent overseas to boost troop morale. He need not have concerned himself for the band would go to England but was there an ulterior motive? While at Yale was Miller recruited for OSS propaganda activities and morale operations and even psychological warfare? It would not have been out of the question. OSS operatives included the cream of Hollywood. Actors Sterling Hayden (John Hamilton), William Holden, Broderick Crawford, Julia Child, Charlotte Gower and Hollywood directors, such as John Ford. After the war Ford produced two movies about the OSS called ‘13 Rue Madeleine’ with James Cagney and ‘Operation Secret’ with Cornel Wilde. They were based in part on the exploits of Colonel Peter Ortiz, one of the most decorated Marine officers of Second World War, who had been a member of OSS since 1943.

OSS and the US intelligence services stopped at nothing that might help the US war effort. They rigged the Norwegian stock exchange. They even enlisted the help of the Mafia and German organizations. In 1941, the security of the port of New York was a matter of great concern, not only to the Third Naval District, but also to the Secretary of the Navy and the President of the United States. Everyone knew that the Mafia controlled the waterfront and Charlie ‘Lucky’ Luciano, who was serving thirty years in prison for prostitution, was obviously an important man in the underworld. Naval Intelligence was extremely concerned about sabotage and espionage on the New York waterfront. They were equally alarmed at the shipping losses. Between 7 December 1941 and February 1942 the US and its allies had lost seventy-one merchant ships to U-boats and by May 1942 272 ships had been sunk along the Eastern Seaboard Frontier. To secure the New York waterfront a Navy–Mafia alliance was concluded and Operation Underworld was born. As part of the deal, on 12 May 1942 Lucky Luciano was moved from the bleak Clinton Prison at Dannemora near the Canadian border to the more comfortable Great Meadow Prison in New York State.

By December 1942 Lieutenant Commander Charles Radcliffe ‘Red’ Haffenden and his staff of fifty officers and eighty-one EM and civilian men were working closely with their mob connections. Early in 1943 the Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI) set up a new department called F-Section to collect strategic information which would assist Husky, the allied invasion of Sicily. The mob co-operated and the greater part of the intelligence developed in the Sicilian campaign came from a number of Sicilians associated with Luciano. Haffenden was delighted and even went as far as proposing that Luciano be released. The mobster remained in prison however, but in February 1946, he was given passage to Italy to spend the rest of his life in exile. He died of a heart attack at Naples airport on 26 January 1962.

Officially, Operation Underworld never happened. On 17 May 1946 in an inter-office memorandum, J. Edgar Hoover, the chief of the FBI, wrote on the report, ‘This is an amazing and fantastic case. We should get all the facts for it looks rotten to me from several angles... a shocking example of misuse of naval authority in the interests of a hoodlum. It surprises me that they didn’t give Luciano the Navy Cross’. On 24 May 1946 after just four months as Commissioner of Marine and Aviation for the city of New York, Haffenden was dismissed.

Towards the end of the war in Operation Sunrise, John Foster Dulles negotiated a separate peace with the German Army in Northern Italy. Six days before VE Day, Operation Sunrise succeeded. Dulles recruited SS General Reinhard Gehlen, head of military intelligence for German forces in the Soviet Union. Gehlen’s information was of substantial interest to those planning the Cold War, so he and his organization were enlisted in the good fight against the Soviets. Gehlen became director of the West German intelligence agency on its establishment in 1955. According to an article by John Loftus in the Boston Globe (29 May 1984) Dulles, with the assistance of the Vatican, engineered the escape of thousands of Gestapo and SS officers. Among these, it now seems likely, were Josef Mengele, Klaus Barbie and possibly Adolf Eichmann. Ex-filtrated Nazis were free to offer their services to Latin American dictators and drug traffickers, as well as the CIA. As Dulles said, ‘For us there are two sorts of people in the world: there are those who are Christians and support free enterprise and there are the others.’

Meanwhile, in the spring of 1944 the AAF orchestra was finally ordered to England. Miller’s arrival there can be attributed to General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the Supreme Allied Commander, who wanted Miller and his band for his brainchild, the AEF (Allied Expeditionary Forces) programme. Ike wanted the programme put out on air to the Allied troops who were taking part in the invasion of France and subsequent campaigns. Despite difficulties, Eisenhower’s persistence, backed by support from Winston Churchill, finally ensured that the AEF programme reached the airwaves and the new programme was inaugurated in March 1944. It went out on air for the first time over the BBC transmitter at Start Point, Devon the day after the successful Allied landings in Normandy, 7 June 1944. Miller and the band, which was now known as the American Band of the Supreme Allied Command, arrived at Gourock, Scotland on 28 June and entrained for London where they were immediately caught up in the V-1 flying-bomb blitz on the capital. Almost 5,000 people were killed. Miller persuaded the top brass to move his unit and on 2 July they left their billet at Sloane Court and travelled to Bedford, 50 miles north of London and safe from flying bombs. On the day after the men had vacated Sloane Court, a buzz bomb fell a few feet from the building, blowing away its entire front and leaving the place in ruins. Ever since 1940 Bedford played host to the major recording and broadcasting departments of the BBC and the Music Department and the BBC Symphony Orchestra, among others, had been moved from London to the comparative safety of Bedford.

At first Miller and his executive officer, Lieutenant Don Haynes, were billeted at the American Red Cross Officers’ Club in Bedford but later Miller was given a flat in Waterloo Road and the band was billeted in two large detached houses in Ashburnham Road. VIIIth Air Force Service Command Headquarters at Milton Ernest Hall on the banks of the Ouse River about 10 miles north of Bedford carried out the day-to-day administration of the band. In between broadcasts and rehearsals at the Co-Partners Hall the band was taken to the headquarters in trucks for its meals. Captain Bob Seymour, in the Communication Section, recalls:

It was about the most pleasant place to be during wartime that one can imagine. Our little post, being the closest military establishment, was designated as the payroll location for Glenn and the band. Some of the band members would hang around our place on days off, play poker or softball. Once in a while we’d have parties and invite the local gentry and some of the lonesome girls from Bedford or Cambridge. Captain Miller usually obliged by bringing out a small all-star band to play for dancing, featuring such renowned sidemen as Peanuts Hucko on woodwinds. One night Glenn goosed my hutmate’s girlfriend on the dance floor resulting in a minor squabble which had to be pulled apart. Probably too much Scotch from our regular RAF ration. A hard life, indeed! But aside from those times we worked hard and did a good job. We kept them flying.

A small detachment from Miller’s AEF band performed for the first time on Saturday evening, 8 July, at a dance for officers of VIIIth Air Force Service Command headquarters at Milton Ernest Hall. On 9 July the Miller band assembled in the Corn Exchange in Bedford for a rehearsal for their first programme, due to be broadcast that night; live on the American Armed Forces (AEF) network. That evening the Corn Exchange was filled to overflowing. Among the audience were some of the biggest names in show-business in America, including Humphrey Bogart and Lieutenant Colonel David Niven, Associate Director of Broadcasting services. Niven reported to Colonel Ed Kirby who had been appointed by SHAEF as Director of Broadcasting services with responsibility for liaison with the BBC. This magical opening performance was followed by hundreds more in England, many of them for troops at American bases throughout East Anglia. The band was so much in demand, especially for radio work, that it became impractical to take the whole unit to every venue. Miller formed sub-sections of the full band to perform different types of music on four radio series. Strings With Wings featured a full string section headed by George Ockner; The Swing Shift, a seventeen-piece dance band led by Ray McKinley; Uptown Hall, a seven-piece jazz ensemble under Mel Powell; and A Soldier and a Song, crooner Johnny Desmond accompanied by the full band.

On 15 December 1944 Glenn Miller is supposed to have vacated Milton Ernest Hall suddenly, leaving Twinwoods airfield for Paris. He was never seen again and his sudden disappearance is still something of a mystery. When it was known that Miller would not be returning, his room at the hall and his flat at Bedford were visited by council workmen who cleared out the contents of his lodgings including one of his last records, ‘Farewell Blues’. It was as if Glenn Miller had never lived there at all or had even existed.

Miller’s disappearance is one of several intriguing episodes in the wartime history of Bedford and its surrounding area. During the Second World War the hall had been the headquarters for the US Army Air Force Service Command but it is not widely known, and many have sought to keep it this way, what other covert activities the hall was put to by the United States military.

From late 1943 Milton Ernest Hall was in the middle of a very intriguing triangle which included many top secret Allied radio and propaganda transmitting stations, political warfare units, undercover British and American units dealing in espionage and subterfuge, as well as the heavy bomber and fighter bases used by the Eighth Air Force First Air Division.

Bletchley Park, Woburn Abbey, Chicksands Priory, North Crawley Grange and Hanslope Park were just a few of the places within the Bedford Triangle that were used by British codebreakers, Secret Intelligence Service (SIS) and the PWE. Why should an area of countryside within a 30 mile radius of Bedford contain so many sites and locations charged with political warfare and covert operations involving espionage, subterfuge and, as we will learn later, clandestine spy-dropping operations?

Certainly, some installations, like Bletchley Park Manor in Buckinghamshire, had been acquired by the British in the late 1930s when war clouds were gathering. The head of the British Government Code and Cypher School (GC and CS) at the outbreak of war was Alastair Denniston, a naval commander. He had already foreseen that expansion of British codebreaking efforts would be extremely important in any future war and had decided that the universities of Oxford and Cambridge would be his best source of personnel. As a result he selected a Victorian country mansion at Bletchley, between both university cities and with good rail links, for the expansion of the GC and CS.

The move from central London to north Buckinghamshire was made in August 1939. At the same time the school was officially renamed Government Communications Headquarters. Bletchley was codenamed Station X and the perimeter of Bletchley Park was patrolled by men of the RAF Regiment.

Bletchley was to be successful in breaking the German Enigma codes. The Ultra codebreaking effort became so large that several other units had to be set up, first in country houses in the area and later in large centres on the outskirts of London. Centres were set up at Gayhurst Manor, 8 miles north of Bletchley and at Wavendon Manor, 3 miles to the north-east. The centres were dispersed to safeguard Ultra from the risk of enemy action should one of the centres be bombed and put out of action. Wrens arriving at ‘Station X’ from London for the soul-destroying but vital job of cypher machine operators found themselves despatched to often pleasant surroundings such as Aspley Guise, Woburn Sands and to a beautiful Tudor house at Crawley Grange, 5 miles north of Wavendon. Houses in Aspley Guise were not just full of bombed-out evacuees from London. Many, known as ‘Hush Hush’ houses, were home for the cryptanalysts and mathematicians who worked at Bletchley Park and for propagandists who worked at Woburn Abbey, home of the Government’s political propaganda unit of the PWE. All described themselves to local people as ‘working for the Foreign Office’.

Doreen Page, who before the war had been a travel courier, was employed by the Foreign Office as a civilian linguist in the Naval Section, working closely with the Wrens. She recalls:

I believe there were about 10,000 people working at Bletchley. I was billeted as a ‘guinea pig’ (so-called because our landladies received just one guinea a week for our keep!) with a family in Newport Pagnell. We were bussed in and out to and from Bletchley by the official transport coaches day and night. I actually worked alternate weeks on day or evening shift most of the time.

Meanwhile, in 1939, the RAF had also set up a listening post at Chicksands Priory, which stands in several hundred acres of ground just west of Shefford, for the purpose of intercepting enemy radio traffic and encoded messages. It is reported that the RAF personnel at Chicksands were instrumental in breaking German codes and permitting the Allies to take advantage of the resulting intelligence information. Much of this, of course, was handled at Bletchley Park Manor.

Late in 1940 Chicksands Priory received the unwelcome attentions of the Luftwaffe, which bombed the facility but only lightly damaged the priory. Chicksands’ other role was in the field of communication. Much of the British radio traffic to support the Allied invasion of North Africa in November 1942 originated from the priory. Chicksands was never short of wireless telegraphy operators because the RAF Radio Communications School was stationed nearby at RAF Henlow.

In addition to the intelligence and propagandist centres and radio communications centres in Buckinghamshire and Bedfordshire there was also a sprinkling of airfields like Tempsford, Cheddington, Harrington and Chelveston, located within easy reach. These airfields were used, amid great secrecy, first by the British secret services and later, jointly by the American OSS, to mount propaganda leaflet raids and to send secret agents into the very heart of German-occupied Europe.

British spy-dropping operations were carried out under the auspices of SOE, which had its beginnings in the dark days of May 1940. Winston Churchill, on assuming the office of Prime Minister and Minister of Defence, aimed to restore British confidence after the military setbacks leading to the resignation of his predecessor Neville Chamberlain, and his first priority was to ascertain from his chiefs of staff whether Britain could fight on alone after the recent collapse of France.

Air Chief Marshal Sir Arthur Harris, Chief of Bomber Command, in particular, was adamant that Germany could only be put out of the war by the calculated and relentless destruction of her industrial and economic might from the air. Britain’s military chiefs were united in one respect. They suggested that the only other way Hitler could be brought down was from within. The Allies had to sow the seeds of discontent and ferment rebellion in the subjugated nations of occupied Europe and Germany itself. This romantic ideal immediately appealed to the swashbuckling Churchill. In July 1940 Dr Hugh Dalton, the Minister of Economic Warfare, was placed in charge of sabotage and subversion and given the job of setting up a new organization called SOE. Churchill’s directive to Dalton was to ‘Set Europe Ablaze’.

The staid and correct military men in the regular branches of the armed services tartly referred to the SOE ‘outcasts’ as ‘The Cloak and Dagger Mob’. In their naïvety the conventional staff officers overlooked the fact that these ‘agents provocateurs’ were in fact brave, highly trained professional killers, armed to carry out a very dirty form of subversive warfare involving assassination, murder, manipulation and sabotage among an implacable enemy whose Gestapo was a feared and ruthless foe.

Despite antagonism from the chiefs of staff and Air Marshal Harris in particular, under the direction of the far-sighted Brigadier Colin McVeagh Gubbins, SOE would grow from humble beginnings in June 1940 (when its headquarters was a small suite of offices at No. 64 Baker Street, London), to a peak of its achievements on D-Day, 6 June 1944. Harris opposed the allocation of valuable aircraft to the infant SOE because it represented a diversion away from the main bomber offensive. Therefore, the aircraft which did find their way to SOE were small in number and not all of them were entirely adequate for special operations.

SOE was responsible for the co-ordination of Resistance operations with Allied strategical requirements in enemy-occupied countries of Europe. The French Resistance was among the leading contenders for arms and equipment. There were four distinct types of French Resistance activity, as identified by M.R.D. Foot, the noted historian: intelligence gathering; running escape and evasion lines; killing Germans; and lastly, political subversion.1 Political subversion existed in France itself and was directed against the Vichy régime. Although all of these activities were closely monitored and assisted by secret organizations in London and Algiers (which provided money while further aid and comfort was provided by the PWE and, later, by the American OSS), their roots were planted in secret outposts scattered throughout the rolling countryside of Bedfordshire and Buckinghamshire.

For the purpose of this story the apex of the Bedford Triangle begins at Harrington. Its eastern side is at Tempsford while its western side includes Woburn Sands and Bletchley. Although much has been revealed about the Enigma code-breaking operation at Bletchley in recent years, the wartime secrecy surrounding SOE and OSS, and even some of the operations mounted from Tempsford and Harrington, is still covered by the Official Secrets Act.

Now, at long last, the triangle is beginning to give up some of its secrets, and conclusions about the disappearance of certain aircraft and their occupants can therefore be drawn.

1Organisation and Conduct of Guerrilla Warfare M.R.D. Foot (Purnell, 1973)

PROLOGUE

Douglas D. Walker

The big ash tree bent to the cold English spring wind, as it had forty years before when the Spitfire fighter plane had ripped through it, cartwheeled into the finance hut and slammed into the ground in front of us. Douglas D. Walker, from Tacoma, Wisconsin, felt the years peeling back to that day in 1945:

The time for going back to England with my wife Jackie to visit the Air Force base from which I had flown in the Second World War had arrived. I had retired from a business career and had plenty of time; our sons had grown and left home; our relatives in Scotland had offered their hospitality and our youngest had offered to house sit.

There were no longer the excuses that had surfaced whenever we had discussed the trip. We both felt fine and, to put the icing on the cake, the fortieth anniversary of VE Day in Europe was coming up on May 8th. It was hard to believe, but the young airman was now a greying retiree and the war was a distant forty years in the past.

May 8th was sunny, but brisk. We mixed with a crowd lining Buckingham Palace Road and waved at Queen Elizabeth and Prince Philip as they drove past on their way to Westminster Abbey for a special service commemorating VE Day.

Three ladies in the crowd with pronounced ‘cockney’ accents talked with us. They had heard our American voices. They asked if I had been in England in the Second World War. I said, ‘Yes, in the 8th Air Force.’ We reminisced about those dark days. They told us about the terror they had experienced night after night during the ‘Blitz’ as the Nazi planes attacked the docks and ships in the Thames River and bombed their homes to rubble. One said, ‘Luv, we was glad to see the war come to an end forty years ago.’ My wife and I solemnly echoed the sentiment.

I remembered the original VE Day forty years before. It had been a joyous celebration as the men on our airbase had welcomed the end of the war in Europe with relieved abandon, shooting pistols and flares into the skies. And why not? There was an immense sense of relief that we would no longer have to face death in those same skies, as we had mission after mission. We – the lucky ones – would soon be going home to our loved ones. Our dead comrades would not. After the first moments of joy, we grieved for them.

Later, while visiting Winston Churchill’s underground war Cabinet offices on Whitehall Street, now open to the public as a museum, we saw Walter Cronkite getting ready to participate in a special BBC VE Day commemorative TV broadcast to America. We paused in awe in front of Winston Churchill’s desk where he had broadcast many of his radio speeches during the Second World War, including his famous, ‘We shall fight them on the beaches, we shall fight them in the streets. . . .’

I remember seeing the great Prime Minister drive by when I was on leave in London one weekend in 1944. His bulldog look was no sham; his defiant rhetoric and adamant stance rallied his people to do their part to help earn ultimate allied victory when, early in the war, it looked like England was doomed to annihilation, as she faced the Nazi war machine alone after the fall of France.

After taking in the sights of London, we rented a car and drove towards Northamptonshire in the ‘Midlands’ section of England. I wanted to see what remained of my old airbase. I had a strong desire to return to this place, which played such an important part in my young life in the Second World War.

Forty years ago, like thousands of other young men, I was based in England as an aircrewman on a B–24 Liberator in the 8th Air Force. I was stationed near Kettering in Northamptonshire, not far from the city of Leicester, about 80 miles north-west of London.

There were many 8th Air Force bases in this section of England. On any given morning, the sky over Northamptonshire would be filled with many hundreds of B–24s and B–17s circling and assembling into units for that day’s bombing attacks on Germany. (More than 26,000 8th Air Force aircrewmen died in the skies over France and Germany in the Second World War.)

My outfit was the 492nd Bomb Group, flying out of Harrington Air Force base. We did not fly normal daylight bombing missions; we flew black Liberators on clandestine missions at night – dropping teams of radio-equipped spies into France and Germany as well as munitions and supplies to underground Resistance forces in France, Denmark and Norway. We bore the nickname Carpetbaggers.

In the spring of 1945, one of our crews parachuted a group of sixteen American commandos of Norwegian descent into the Jaevsjo Lake area of Norway, along with ten tons of explosives and supplies. Jaevsjo Lake is located near the Swedish–Norwegian border. These commandos were a special arm of the OSS (the forerunner of the CIA) and, joining up with a small group of Norwegian Resistance fighters, they proceeded to blow up rail lines and bridges, cutting the main north–south railway lines. Outnumbered ten to one, the commando force completed their missions and managed to outrun their Nazi pursuers in a demanding 50 mile ski chase into the mountains. They successfully evaded the Nazi patrols until the end of the war.

Two of our aircrews from Harrington crashed during the first four attempts to land additional commandos and supplies in the mountainous Jaevsjo Lake area, killing sixteen aircrewmen and ten commandos. These crashes were due to the exceptionally severe weather conditions in the Norwegian mountains in early 1945. Our crew was one of the lucky ones – we had to turn back on a mission to this area during that period after encountering blinding blizzards and heavy icing conditions.

As I drove along looking at the rolling, mist-shrouded landscape I had known so well from the air forty years previously, I began to remember faces of long-forgotten friends, as well as incidents I had tucked away in my ‘memory bank’ and now recalled with exact detail. I turned to my wife and told her about a sunny morning in February 1945 when I was strolling to the mess hall with a few friends to have lunch. We had noticed an English Spitfire fighter plane landing on the runway nearby (this did not surprise us – many English pilots landed at our base to purchase American cigarettes and candy bars). The pilot hopped out, strolled in our direction and stopped to chat with us. He was a member of the Free Polish Air Force and was just finishing his training. We invited him to join us for lunch. During lunch we learned how, as a child, he had fled from the Germans when they had invaded his country and how he had waited impatiently to be old enough to join the Free Polish Air Force so that he could ‘fight Messerschmitts’.

As we parted company, he told us to watch him – he was going to perform a ‘fly over’ and show us some ‘fancy flying’. We watched as he skilfully threw his Spitfire into a series of aerobatics, until, in horror, we saw him dip too low to the ground: a wing ripped through a nearby tree, then the plane smashed into the finance hut and dug a hole into the ground near us.

We ran to help him, but there was nothing we could do. We watched helplessly as he was pronounced dead by the medics. Fortunately, the loss of life was not greater; the two men normally in the finance hut were in the mess hall when the accident happened.

I also remembered a happier time when I had travelled to Aberdeen, Scotland on a three-day pass to see my grandparents, whom I had not seen since I was four. I recalled how their eyes had lit up when I had unpacked five pounds of sugar, a large tin of Spam and three pounds of butter – through the courtesy of a friendly mess sergeant. They hadn’t seen food like that since wartime rationing started in 1940.

My base had been located at Harrington, a one-pub hamlet about 5 miles from the town of Kettering. Because I didn’t think I could locate the place without help, I followed my wife’s suggestion and stopped at the police station in Kettering. I didn’t think that the young sergeant on duty would be able to help me as it was obvious he wasn’t even born when the war was on. However, surprisingly, he knew all about the history of the airfield and was able to give me exact directions. He regretfully pointed out that I wouldn’t see much evidence of the airbase. Seems they had torn it down after the war to resume farming operations. However, he said we might see some pieces of the original concrete runway.

As we drove, the weather turned nasty. A cold north-east wind was blowing and premature dusk was setting on. We drove over single-track roads surrounded by rolling farmlands and very little sign of habitation. Finally, we reached the general area described by the police sergeant. It was in the midst of hundreds of acres of farmland. I could see no familiar traces of the airbase, not even any pieces of the old concrete runway. I was beginning to feel despondent.

The contrast was even more sombre, comparing this pastoral scene with one forty years previously, when the area had been a bustling beehive of activity, with more than a thousand men and dozens of airplanes creating a busy and vital aerodrome.

It was now darker. I started to turn the car around to leave when I noticed an old stone farmhouse in the distance. I decided to talk with the inhabitants to see if they could help me find some remnants of the base.

Two fat geese snapped at me as I left the car to knock on the door. There was no response to my knocking. I backed the car up to leave, just barely missing the geese, when I noticed a big man approaching the car with a dog at his heels. He was dressed in work clothes and boots.

I stopped, opened my window and began to explain that I was an American who had been stationed at Harrington air base during the Second World War and had returned to try to find the place. Halfway through my explanation he gave a big friendly smile, and when I had finished, swept his hand towards the farmhouse and invited us in. He said, ‘Any 8th Air Force man is welcome here. Come on in with your fine lady and I’ll give you all the information you need.’ He cheerily introduced himself as John Hunt. My falling spirits took a quick upturn.

We followed him into the farmhouse, which we later learned was over 300 years old. His wife Angela proved to be an attractive and intelligent mother of two girls, who hadn’t heard my knocking because she was bathing the children.

Jackie and I sat down in their living room in front of a cheery gas burner to get rid of the May chill, as Mr Hunt took out an illustrated book on the history of the RAF and US Air Force operations in Northamptonshire. He pointed to a picture of a black Liberator taking off from Harrington with a nearby farmhouse in the background. I recognized the farmhouse as one that had stood across the street from our quarters. He indicated that it was still there. There was an accompanying article about the operations of our base and about our clandestine missions during the war.

John admitted that even though he had been only a few months old at the start of the war, he had become a ‘buff’ concerning air operations in the Second World War and knew all about the operations of the 8th Air Force bases in the vicinity, including a special interest in Harrington due to its proximity to his farm. I had found the right man at last.

John said that he had become familiar with Harrington Air Force base in the late fifties when he used to ride a motorbike on the old runways. He remembered the government removing the Nissen hut barracks and 200 acres of concrete runway, tarmacs and revetments to turn the acreage back into farming.

He also remembered the demolition of the control tower complex. ‘But’, he said, ‘your old brick administration building is still standing, together with a mess hall.’ I felt better. At least I would get to see something of the old base.

John was also familiar with other 8th Air Force bases in the vicinity, such as a nearby B–17 base at Grafton Underwood. We later drove there to see a marble monument honouring the men of the 384th Bombardment Group, which flew from that base. The 384th enjoyed a singular achievement: they dropped the first US Air Force bombs on Germany in 1942 and the last bombs in 1945.

I remembered this base. They were only 3 miles from us. One morning there was a tremendous blast which shook our quarters. We rushed out to see a plume of black smoke rising into the sky in the direction of Grafton Underwood airbase. Later, we learned that a B–17 fully loaded with fuel and 500 lb bombs had crashed on take-off, killing all ten of the crew and injuring crews on two other bombers awaiting take-off. In all, the 384th lost more than 1,600 young aircrew flyers in two years of operations against Germany.

John offered to show my wife and me what remained of the Harrington air force base if we would return the next morning. We readily accepted and drove to Kettering and stayed at the Royal Hotel for the night. The back of the menu in the hotel dining room featured a copy of a letter written by Charles Dickens to his wife in London while a guest at the hotel in 1835.

The next morning was cold and drizzly. The wind whipped up suddenly, but I didn’t mind a bit. Finally, after forty long years, I was about to return to the wartime scenes of my youth, along with the girl who had patiently waited for me to come back.

As we drove through the first of several open gates, John waved to a man watching us from the front yard of a modern farmhouse. He explained that this man was the farm manager for the owner, the late Sir Gerald Glover. I asked how he achieved the knighthood and learned that he received the honour as a result of his wartime services, ‘in the same type of clandestine spying as you chaps, but on the British side of things’. John went on to explain that Sir Gerald had purchased the majority of the 800–acre airbase after the war to conduct farming operations.

We drove deeper into the farm pastures over rutted and muddy roads. Now and then we would ride over concrete surfaces and John would point out old revetments where bombs were stored – or fuel dumps – or airplane tarmacs and portions of old service roads. Most of the decaying installations in the area were overgrown with weeds and bushes.