Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Polygon

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

- Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

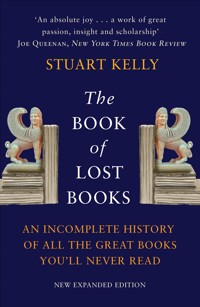

The Book of Lost Books is a book of stories involving kings, heretics, untimely interruptions and back room deals, falling tortoises and fairy princesses, train crashes and war atrocities, bravery, cowardice, rent boys, chamber maids, love, quests, puzzles and a crocodile. From Homer to Jane Austen, Shakespeare to Ernest Hemingway, this is an account of books destroyed, misplaced, never finished, or never even begun. With academic shaggy dog stories, swashbuckling historical fables, wry ironies and imaginative fantasia, The Book of Lost Books is the perfect read for all bibliophiles. Hilarious, insightful, endlessly fascinating, sometimes shocking - The Book of Lost Books is a wonderfully quirky but utterly romantic saga of our love affair with books.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 620

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

THE BOOK OF LOST BOOKS

‘Kelly’s narrative moves with the ease of an after-dinner conversation between bibliophiles, and his love of books is patent’

The Times Higher Education Supplement

‘Kelly has let his eye beam around the gaps in the libraries of the world, and there are essays on great works that have disappeared – books unheard of or otherwise’

Muriel Spark, Sunday Telegraph

‘Charming and erudite’ Sunday Telegraph

‘Kelly hugs the shore of serious, mainly classical literature with barnacle tenacity . . . will appeal to those with incurable bibliomania’

Sunday Herald

‘My top pick (for non-fiction) Kelly describes lost works by the world’s most famous writers, from ancient Greece to modern times. It’s a fascinating work that wears its erudition lightly, and offers a sobering reminder that every book eventually becomes a lost one’

Andrew Crumey, Scotland on Sunday, Books of the Year

‘Kelly wears his considerable scholarship lightly [and] he has packed an incredible amount of research into this book: a lively and entertaining work that can be enjoyed equally as a straight-through read or a random browse . . . leaves you feeling not only cleverer at the end, but entertained as well’

Scotland on Sunday

‘Erudite and entertaining . . . allowing us to play endless “What if?” games with the classics of world literature’

London Review of Books

‘Clever, funny and informative . . . it is a weird history of literature. Identifying books by authors from Homer and Agathon to Flaubert, Bruno Schulz and Sylvia Plath that either went missing or in some cases never got written, Kelly fills you with longing for more books in the world, and more time to read them all’

Lucy Ellman, Sunday Herald

‘An entertaining and sobering book about mutability, impermanence and loss. None of his readers will ever feel the same about the printed word’

The New York Sun

‘Often witty and sometimes poignant . . . The Book of Lost Books leaves us pensive, imagining all the works that are well and truly lost, even beyond “Anonymous,” and thankful for what remains’

Jane Smiley, L. A. Times Book Review

‘The most pleasurable book I’ve read in a good five years . . . What book could possibly deserve prominence more than this exquisite history of literary paradise lost?’

Jeff Simona, Buffalo News

‘Lifelong study of the Stuart Kelly lost literature of this new book just published, summarizing, reviewed the history of his suicide note, and he is a lost masterpiece of the greatest minds of the list’

Google translation of Beijing Post review

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Stuart Kelly was born in 1972 and is Literary Editor of Scotland on Sunday. He is also the author of Scott-land: The Man Who Invented A Nation and runs the blog www.mcshandy.wordpress.com. He is married and lives in Edinburgh.

This eBook edition published in 2012 by Birlinn Limited West Newington House Newington Road Edinburgh EH9 1QSwww.birlinn.co.uk

First published in 2005 by Viking This revised edition published in 2010 by Polygon, an imprint of Birlinn Ltd

Copyright © Stuart Kelly, 2010 Illustrations copyright © Andrzej Krauze, 2010

The moral right of Stuart Kelly to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form without the express written permission of the publisher.

ISBN: 978-1-84697-123-5 eBook ISBN: 978-0-85790-525-3

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

This book is for Sam, who found me

Contents

Acknowledgements

Introduction

Anonymous

Homer

Hesiod

The Yahwist, the Elohist, the Deuteronomist, the Priestly Author and the Redactor

Sappho

K’ung Fu-tzu

Aeschylus

Sophocles

Euripides

Agathon

Aristophanes

Xenocles and Others

Menander

Callimachus

The Caesars

Gallus

Ovid

Longinus

Saint Paul (Saul of Tarsus)

Origen

Faltonia Betitia Proba

Kālidāsa

Fulgentius

Widsith the Wide-travelled

The Venerable Bede

Muhammad Ibn Ishaq

Ahmad ad-Daqiqi

Dante Alighieri

Geoffrey Chaucer

François Villon

John Skelton

Camillo Querno

Luis Vaz de Camões (Camoens)

Torquato Tasso

Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra

Edmund Spenser

William Shakespeare

John Donne

Ben Jonson

John Milton

Sir Thomas Urquhart

Abraham Cowley

Molière (Jean-Baptiste Poquelin)

Jean Racine

Ihara Saikaku

Gottfried Wilhelm von Leibniz

Alexander Pope

Dr Samuel Johnson

The Rev. Laurence Sterne

Edward Gibbon

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

Robert Fergusson

James Hogg

Sir Walter Scott

Samuel Taylor Coleridge

Jane Austen

George Gordon, Lord Byron

Thomas Carlyle

Heinrich Heine

Joseph Smith Jnr

Nikolai Gogol

Charles Dickens

Herman Melville

Gustave Flaubert

Fyodor Dostoyevsky

Sir Richard Burton

Algernon Charles Swinburne

Emile Zola

Arthur Rimbaud

Frank Norris

Franz Kafka

Ezra Loomis Pound

Thomas Stearns Eliot

Thomas Edward Lawrence

Bruno Schulz

Ernest Hemingway

Dylan Marlais Thomas

William S. Burroughs

Robert Traill Spence Lowell IV

Sylvia Plath

Georges Perec

Conclusion

Another Introduction

Hypereides

Mani

Guṇāḍhya

The Yongle Encyclopaedia

The Makers

Henslowe’s Diary

Pierre de Fermat

Emily Brontë

Daniel Paul Schreber

Philip K. Dick

Acknowledgements

Many friends and colleagues have endured incessant questions about their own specialities; many of them have also regularly sent me details about lost books they encountered in their own work. I would like especially to thank Gavin Bowd, Seán Bradley, Peter Burnett, Angus Calder, Andrew Crumey, Lucy Ellmann, Todd McEwen, Richard Price and James Robertson. Peter Straus, Leo Hollis, Kate Barker, David Ebershoff, David Watson and Sam Kelly were all unstintingly helpful in terms of the actual writing; and, of course, thanks to my parents, who started, and endured, my whole obsession with reading.

‘Hence, perpetually and essentially, texts run the risk of becoming definitively lost. Who will ever know of such disappearances?’

Jacques Derrida, ‘Plato’s Pharmacy’

Introduction

‘I’ll burn my books – ah, Mephistophilis’

Christopher Marlowe, Doctor Faustus

My mother claims it started with the Mr Men series of children’s books. In a well-rehearsed pantomime of parental exasperation, she recounts how, after a family relative had given me a copy of one of Roger Hargreaves’ stories, every holiday jaunt, weekend outing and Saturday shopping trip became a single-minded trawl of bookshops until I had every single one of the series. Mr Bump needed Mr Nosey, Mr Tickle was lonely without Mr Chatterbox. After I had finished this first collection I swiftly became obsessed, I forget for what reason, with the Dr Who novelizations; this was followed by ‘Fighting Fantasy’ dice and decision books, and, as I approached my teens, Agatha Christie paperbacks.

A pattern began to develop; a pattern that would turn obsessive. Having one or some of the titles within any given series was not sufficient; I seemed to be afflicted with a relentless monomania for all, a near-compulsive necessity for closure and completeness. I even kept a ‘Book of Lists’, to double-check that I really did know every episode of Dr Who, with ticks against the ones I had bought and annotations about the ones that had never been novelized. When all of Agatha Christie’s books were reissued with newly designed covers, the idea of having mismatched volumes struck me as unspeakably grotesque. I stalked the old stock, ferreted for the forgotten copies at the back of the shelves.

It must have been with some trepidation, on my fourteenth Christmas, that my parents watched me unwrap a Complete Works of Shakespeare (Chancellor Press, 1982, printed in Czechoslovakia) and a selection of Wordsworth (by W. E. Williams, introduction by Jenni Calder, Penguin Poetry Library, 1985). I presume that they were hoping that Literature – with a capital L – was a large enough field in which my fixation might peter out.

Instead, Literature drove my zeal to new heights. The itch became a palpable rash when I started studying Greek (initially as a shameless ruse to avoid sports). Having saved up months of weekend-job wages, and having starved myself rationing lunch money, I binged on Penguin Classics of Hellenic drama: two volumes of Aeschylus, two of Sophocles, three of Aristophanes, four of Euripides and a solitary Menander. The first shock to my well-ordered system came as I peeled back the smart covers and began to browse through the introductions. I was under the impression that I had just bought all of Greek drama, yet the prefaces and commentaries doomfully tolled otherwise: Aeschylus, whose seven plays I was holding, had actually written eighty; there should have been thirty-three volumes of Sophocles, not a mere brace . . . and so on.

The second, more grievous realization came when reading note 61 to Aristophanes’ play Thesmophoriazusae: ‘Agathon, one of the most celebrated tragedians of the day, was forty-one when this play was produced. None of his works has survived.’ None? Not a chorus, not a speech, not a hemistich? It seemed unthinkable.

This, I decided, at the age of fifteen, was a situation which I should rectify. I started compiling a List of Lost Books. It quickly superseded my Book of Lists with its ‘Everyone in Star Wars That Wasn’t Made into a Figure’, ‘Dr Who Episodes Lost by the BBC’ and even the list of books that I should read. This new list would be of the impossible and the unknowable, of books that I would never be able to find, let alone read.

It soon became clear that the subject was not limited to the Greeks, who, after all, had managed to keep on existing through Roman arrogance, Christian lack of interest and a certain Caliph’s censorious view of libraries in general and the Alexandrian Library specifically.

From Shakespeare to Sylvia Plath, Homer to Hemingway, Dante to Ezra Pound, great writers had written works which I could not possess. The entire history of literature was also the history of the loss of literature.

It is intrinsic to the nature of literature that it is written: even work initially preserved in the oral tradition only truly becomes literature when it is written down. All literature thus exists in a medium, be it wax, stone, clay, papyrus, paper or even – as in the case of the Peruvian knot language, Khipu – rope. Since it has a material dimension, literature itself partakes of the vulnerability of its substance. Every element conspires against it: flame and flood, the desiccating air that corrupts, the loamy earth that decays. Paper is particularly defenceless: it can be shredded and ripped, stained and scrubbed away. Countless living things, from parasites and fungi to insects and rodents, can eat it: it even eats itself, burning in its own acids.

The simplest form of loss is destruction. Though the Roman poet Horace proclaimed, ‘I have built a monument more durable than bronze,’ he expressed a hope about his work, and not a certainty. The nineteenth-century poet Gerard Manley Hopkins burned all of his early poetry, as he dedicated his life to the beauty of God. James Joyce petulantly flung Stephen Hero, the first draft of A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, into the fire, but did not prevent his wife from saving what she could of it. Mikhail Bakhtin, exiled in Kazakhstan, used his work on Dostoyevsky as cigarette papers, after having smoked a copy of the Bible.

Some writings are absent, presumed destroyed: Socrates, while in prison awaiting his execution, wrote versifications of Aesop’s Fables. None of these have survived, and we rely on Plato’s remembered and invented dialogues to catch even an echo of what Socrates himself might have written. Similarly, at some point, the only text of Aristotle’s second book of Poetics was lost, and even the first book is made up from students’ notes. A similar fate happened centuries later to Ferdinand de Saussure’s Course in General Linguistics. When the publisher John Calder had to hastily relocate his offices in late 1962, many manuscripts – including The Sowing, the third part of Lars Lawrence’s trilogy, and Angus Heriot’s The Lives of the Librettists – were left behind in the old premises. The building, unpublished works and all, was demolished. If any undiscovered genius had sent their sole copy to Calder, undiscovered they would remain.

There are other works which are lost in the sense of being misplaced. A suitcase containing Malcolm Lowry’s Ultramarine was stolen from his publisher’s car, and the version we have had to be reconstructed from what was left in Lowry’s bin. Allen Ginsberg recollected hearing fellow beat poet Gregory Corso reading in a lesbian bar in the Village, though you can search in vain through Corso’s published oeuvre to find a poem with the line he remembered: ‘The stone world came to me, and said Flesh gives you an hour’s life’. How Ginsberg knew that Flesh was capitalized is a moot point.

There are also those manuscripts that meet an untimely end, whose authors’ mortal existence is concluded before their work. The medieval Scottish poet William Dunbar wrote a haunting elegy for many of his dead fellow writers: of the twenty-two poets he lists, there are ten about whom we know nothing whatsoever. Virgil left instructions for The Aeneid to be torched, since he had not polished it to perfection. Sir Philip Sidney wrote the Arcadia once, but his own massive expansion of the work was abruptly terminated by a bullet on the battlefield at Zutphen. Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The Dolliver Romance, Robert Louis Stevenson’s Weir of Hermiston and William Makepeace Thackeray’s Denis Duval are all partial classics. The SS put paid to the radical theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s disquisition on ethics. Robert Musil and Marcel Proust never quite perfected their similarly voluminous masterpieces; and though we have enough extant to make them ‘classics’, a doubt scratches around these incomplete, unfinished, permanently paused novels.

The final category of lost books is the eternally embryonic works that the author planned and worked on, but never actually got round to the business of writing. Solon, the Athenian legislator, was too busy introducing income tax to turn the story of Atlantis into verse. The philosopher Boethius never managed to create his proof that Plato and Aristotle were in strict agreement. Sheridan told everyone that the sequel to The School for Scandal was going to be called Affectation, but did not bother writing it. Daudet’s The Pentameron and Victor Hugo’s La Quinquengrogne are both perpetually forthcoming. Lewis Grassic Gibbon was prevented from even beginning the novel he described in a letter as ‘McLorna McDoone’, and who knows whether or not Sir Arthur Conan Doyle might not have planned to reveal the true story behind the Giant Rat of Sumatra, which Watson once alluded to whilst Holmes was engaged with more immediate cases? Would Thomas Mann’s Gaia have been the masterpiece while it was unwritten he believed that it could be? Would Nabokov’s never-written Speak, America, the follow-up to his volume of memoirs, Speak, Memory, have told us more about the composition of Lolita or his triumphs in butterfly-collecting? Often these works are so ambitious their completion seems intrinsically impossible: Novalis’ Encyclopedia, covering all human knowledge, progressed little beyond his anxieties about whether the contents list would also serve as an index. Likewise, Leopardi’s Encyclopedia of Useless Information is incomplete: one wonders what he would have made of the Internet.

One other category of lost books exists but, with an unreasonable optimism about the future, I have chosen not to discuss the illegible. Languages such as Linear A, Mayan and the Easter Island Script have not been deciphered, and might therefore be considered to contain whole lost literatures: however, after being thought incomprehensible for millennia, the decryption of the Rosetta Stone in the nineteenth century meant hieroglyphics could now, tentatively, be read. If this book is on the quanta-net in 5005, I would not wish my descendants to be troubled with having to make any deletions.

Loss has symptoms and predilections. Comedy displays many of the high-risk features, as do erotica and autobiography. The loss of Philip Larkin’s diaries, combining all three of these genres, was almost inevitable. The censuring of the erotic also accounts for the loss of a book by the Abbasid court poet Ibn al-Shah al-Tahiri (whether panegyric, satire or handbook can never be known) entitled Masturbation. Over and above the content of the work, the multiplicity of theological and political regimes under which a piece of writing might find itself – its nurture, rather than nature, if you will – contribute towards extinction.

From Savonarola to the Ayatollah Khomeini, religions have expressed themselves through book-burning. Valentin Gentilis, who lived in Geneva, wrote a discursive piece on the idea that Calvin’s Trinitarian doctrine inadvertently posited a Fourth Member of the Godhood. He was imprisoned for eight years, recanted and then was executed: his punishment (apart from the deprivation of life) was first to burn his own work. His sentence was considered light.

The fact that Mandelstam’s blisteringly satirical ‘Stalin Ode’ survived at all is remarkable; many others of his papers, drafts and scribbles were burned, flushed and otherwise discarded. His compatriot Isaac Babel was not so lucky. When he was arrested by Stalin’s secret police on 15 May 1939, agents removed every single piece of paper from his flat.

Certain authors, rather than certain works, become suspect. That there are not more entries on women writers, gay writers and writers from outwith Europe, and the English language, is partially my own fault, and partially the fault of those who systematically erased that work. Virginia Woolf famously tried to imagine Shakespeare’s sister, but the inexorable and unchangeable nature of the past frustrates any attempt at giving a name to those who have been deprived of even a ghostly lost existence. In their place, with a few exceptions, I will concentrate on the so-called Canon. The much-vaunted Western Canon, trumpeted abroad for its wealth, happiness and strength, is not an Olympian torch or a thoroughbred horse; it exists by chance, not necessity, a lucky crag protruding from an ocean of loss. That melancholy parade of disfigured busts, crazed ceramics, blistered portraits and foxed photographs is here, in all its shoogly, precarious glory. They are our conditional, might-have-been-otherwise, sheer damn lucky tradition. Those overwhelmed by Time’s corrosion are not so fortunate.

Is becoming lost the worst that can happen to a book? A lost book is susceptible to a degree of wish fulfilment. The lost book, like the person you never dared ask to the dance, becomes infinitely more alluring simply because it can be perfect only in the imagination.

We are, nowadays, almost incapable of believing in loss. As Project Gutenberg and databases like the Chadwyck-Healy continue to grow, and offer the idea of a perma-fixed cyberspace culture, it is important and humbling to recognize that there is no automatic afterlife for literature. Prizes and plaudits are awarded on a daily basis; yet the ultimate fate of those lucky recipients is no more secure than that of the great prize-winner Agathon. Even a repository like the British Library used to have old request slips with a box on the back, infrequently but occasionally ticked, stating ‘Volume lost’. There is, equally, no guarantee that an intangible existence is also an unreachable state of being. If literature were a house, The Book of Lost Books would be Rachel Whiteread’s House, a poured-into vacancy that is both tomb and trace. The Book of Lost Books is an alternative history of literature, an epitaph and a wake, a hypothetical library and an elegy to what might have been.

On the Absence of a Bibliography and Footnotes in this Work

Zora Neale Hurston, the American folklorist and black activist, who left a novel entitled Herod the Great unfinished at her death, defined research as ‘formalized curiosity’. It is, I think, a liberating definition. There seems to me to be a terrible irony in trying to create a bibliography for The Book of Lost Books: the substance is, by its nature, not in any library or collection. I could, I suppose, display the chain of references that took me, for example, from Aeschylus’ Oresteia translated by Robert Fagles to Gilbert Murray’s Aeschylus to volume ten of the works of the theologian Athenaeus; but where would this chain end? Not, assuredly, in the actual lost book, but in the whisper of its disappearance. For a book like this, footnotes are a trail to an empty grave.

Rather than marshal the reader along the meanders and diversions that my own formalized curiosity led to, I would, however, prefer her or him to set out on their own adventure. There are obvious places to start: every moderately well-stocked public library should, at least, contain either the Columbia or Britannica Encyclopedia, which offer an array of further routes to choose. I would also recommend Margaret Drabble’s Oxford Companion to English Literature, The Cambridge Companion to Women’s Writing, The Oxford Companion to Classical Literature, Edward Browne’s Literary History of Persia, Suchi Kato’s History of Japanese Literature, Ian Hamilton’s Keepers of the Flame, Rosier’s Encyclopedia and . . . but already this is looking like a reading list.

Most of the authors discussed in this book did leave behind extant works, and the reader can choose, for the most part, between numerous editions: Penguin Classics, The World’s Classics, Everyman, the Modern Library. Lost books is a practically infinite subject; and there are many – Acacius’ Life of Eusebius, Eusebius’ Life of Pamphilus, works by Anna Boškovic and Denis Fonvízin – that, through reasons of space, obscurity or indolence, did not make it into this book. The curious reader will no doubt find many more, and may find many more interesting. They may even find a book hitherto thought lost: the Scottish poet John Manson recently discovered, amongst various papers and ephemera in the National Library of Scotland, an almost complete text of the modernist poet Hugh MacDiarmid’s ‘lost’ magnum opus, Mature Art.

According to the Latin poet Horace, the function of writing was to instruct and delight. If The Book of Lost Books manages to whet and divert readers sufficiently that they begin their own peregrinations among the plenitude of books that remain, it will have done everything I hoped.

Anonymous

(c.75,000 BCE–c.2800 BCE)

The very origins of literature are lost.

An oblong piece of ochre, found in the Blombos Caves on the southern coast of present-day South Africa, is crosshatched with a regular pattern of diamonds and triangles. It is 77,000 years old. Whether these geometric designs are supposed to be symbolic, whether they are supposed to mean anything at all, they present us with one irrefutable fact. A precursor of modern humanity deliberately engraved marks on to a medium. It was a long way yet to the word-processor and text messages, but a first step of sorts had been taken.

The period around 45,000 to 35,000 years ago in humanity’s evolution has been called the Upper Palaeolithic Revolution or, more catchily, the Creative Explosion. More complex tools were fashioned, from fish-hooks to buttons to needles. Moreover, they are decorated, not only with schema of lines and dots: a lamp contains an ibex, a spear-tip transforms into a bison. There are also statuettes with no immediately discernible use; squat figurines of dumpy women. Is it possible to have slings but not songs, arrows but not stories?

Looking at the cave-paintings from Lascaux, Altamira and Chavette, created some 18,000 years ago, it is overwhelmingly tempting to try and read them. Do these images record successful hunts, or are they imagined desires and hopes? Is this ‘Yesterday we killed an aurochs’ or ‘Once upon a time there was an aurochs’? What do the squiggles and zig-zags, the claviforms and tectiforms over the animal images signify? Occasionally, looming out from an inconceivably distant time, a human hand print appears, outlined in pigment. A signature, on a work we cannot interpret.

Where did writing come from? Every early culture has a deity who invents it: Nabu in Assyria, Thoth in Egypt, Tenjin in Japan, Oghma in Ireland, Hermes in Greece. The actual explanation may be far less glamorous – accountants in Mesopotamia. All the earliest writing documents, in the blunt, wedge-shaped cuneiform style, are records of transactions, stock-keeping and inventories. Before cursives and uncials, gothic scripts and runic alphabets, hieroglyphics and ideograms, we had tally-marks.

But, by the first few centuries of the second millennium BCE, we know that literature has begun, has begun to be recorded, and has begun to spread. It was not until 1872 that the first fragments of The Epic of Gilgamesh resurfaced in the public domain after four millennia. The excavation of ancient Nineveh had been undertaken by Austen Henry Layard in 1839. Nearly 25,000 broken clay tablets were sent back to the British Museum, and the painstaking work of deciphering the cuneiform markings commenced in earnest. The Nineveh inscriptions were incomplete, and dated from the seventh century BCE, when King Assurbanipal of Assyria had ordered his troops to seek out the ancient wisdom in the cities of Babylon, Uruk and Nippur. These spoils of war were then translated into Akkadian from the original Sumerian.

Over time, the poem was supplemented by more ancient versions discovered in Nippur and Uruk, as well as copies from places as far apart as Boghazköy in Asia Minor and Megiddo in Israel. Gradually, an almost complete version of The Epic of Gilgamesh was assembled out of Hittite, Sumerian, Akkadian, Hurrian and Old Babylonian.

Who first wrote it? We do not know. Was it part of a wider cycle of myths and legends? Possibly, even probably, and there is a slim chance that further archaeological research will answer this. What, finally, is it about?

Gilgamesh is a powerful king of Uruk. The gods create an equal for him in the figure of Enkidu, a wild man, brought up among beasts and tempted into civilization by sex. They become firm friends, and travel together to the forest, where they slay the ferocious giant Humbaba, who guards the cedar trees. This infuriates the goddess Ishtar, who sends a bull from Heaven to defeat them. They kill and sacrifice it, and Ishtar decides that the way to harm Gilgamesh is through the death of Enkidu. Distraught, Gilgamesh travels through the Underworld in search of eternal life, and eventually meets with Utnapishtim at the ends of the world. Utnapishtim was the only human wise enough to escape the Flood, and, after forcing Gilgamesh through a purification ceremony, shows him a flower called ‘The Old Are Young Again’. It eludes his grasp, and Gilgamesh dies.

The themes resonate through recorded literary endeavour. Gilgamesh wrestles with mortality, he declares he will ‘set up his name where the names of the famous are written’. Death is inevitable and incomprehensible. Even the giant Humbaba is given a pitiable scene where he begs for his life. Prayers, elegies, riddles, dreams and prophecies intersperse the adventure; fabulous beasts sit alongside real men and women. The fact that we can discern different styles and genres within The Epic of Gilgamesh hints that unknown versions existed prior to it.

All the earliest authors are anonymous. A legendary name, an Orpheus or Taliessin, serves as a conjectural origin, a myth to shroud the namelessness of our culture’s beginnings. Although anonymity is still practised, it is as a ruse to conceal Deep Throats, both investigative and pornographic. It is a choice, whereas for generations of writers so absolutely lost that no line, no title, no name survives, it is a destiny thrust upon them. They might write, and struggle, and edit, and polish, yet their frail papers dissipate, and all their endeavour is utterly erased. To those of whom no trace remains, this book is an offering. For we will join them, in the end.

Homer

(c. late eighth century BCE)

Homer was . . .

The verb’s the problem here. Was there even such a person as Homer?

There was, or there was believed to be, a Homer: minds as sceptical as Aristotle’s and as gullible as Herodotus’ knew there was, of sorts, a, once, Homer.

‘When ’Omer smote ’is bloomin’ lyre . . . They knew ’e stole; ’e knew they knowed . . .’ says Rudyard Kipling.

‘But when t’ examine ev’ry part he came. Nature and Homer were, he found, the same,’ was Pope’s interpretation.

Samuel Butler, in ‘The Authoress of the Odyssey’ (1897), proposed that at least half of Homer was a woman.

E. V. Rieu, in 1946, patriotically complained:

Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey have from time to time afforded a first class battleground for scholars. In the nineteenth century in particular, German critics were at endless pains to show, not only that the two works are not the product of a single brain, but that each is a piece of intricate and rather ill-sewn patch-work. In this process Homer disappeared.

The imperishable Homer dwindles, a hum, an er, an inconclusive pause. Let’s begin with what we know: Il. and Od. Two long poems exist, The Iliad and The Odyssey, and somehow someone somebody called Homer became convoluted within them.

The Iliad and The Odyssey were considered by the Greeks to be the pinnacle of their literary achievements, and subsequent centuries and countries have concurred. Egyptian papyrus fragments of the texts outnumber all other texts and authors put together; they are the basis for many of the tragedies and are quoted, almost with reverence, by critics, rhetoricians and historians. It is tempting to extract information about the poet from the poetry, as did Thomas Blackwell, who, in ‘An Enquiry into the Life and Writings of Homer’ (1735), found such a happy similarity between the work and the world. Or, like the archaeologist and inveterate pilferer Schliemann, one might scour the coasts of Asia Minor in search of hot springs and cold fountains similar to those in the verse. But Homer, himself, herself, whatever, is irredeemably slippery.

Take customs. Bronze weaponry is ubiquitous in The Iliad, and iron a rarity, leading one to assume the poem describes a Mycenean Bronze Age battle. Yet the corpses are all cremated, never interred, a practice associated with the post-Mycenean Iron Age. The spear and its effect are historically incompatible. The language itself bristles with inconsistencies. Predominantly in the Ionic dialect, there are traces of the Aeolic, hints of Arcado-Cypriot. Are these the snapped-up snatches of a wandering bard, linguistic sticky-burrs hitching on to the oral original? Or the buried lineaments of disparate myths corralled into a cycle, the brick from a Roman villa reused in the Gothic cathedral? The artificer cannot be extrapolated from the artefact.

To the Greeks, The Iliad and The Odyssey were not the works of a poet, but the Poet. So impressed were the people of Argos with their inclusion in The Iliad that they set up a bronze statue of Homer, and sacrificed to it daily.

Seven cities – Argos, Athens, Chios, Colophon, Rhodes, Salamis and Smyrna – claim to be the birthplace of Homer, although, significantly, all did so after his death. When he was born is just as contentious: Eratosthenes places it at 1159 BCE, so that the Trojan War would have still been in living memory, though a plethora of birthdates up until 685 BCE have been offered. Most opt for the end of the ninth century BCE, a convenient average of the extremities. His father was called Maeon, or Meles, or Mnesagoras, or Daemon, or Thamyras, or Menemachus, and may have been a market trader, soldier or priestly scribe, whilst his mother might be Metis or Cretheis, Themista or Eugnetho, or, like his father, Meles.

One extensive genealogy traces him back to his great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-grandfather, the god Apollo, via the mythic poet Orpheus and his wife, the muse Calliope (though she has also been advanced as his mother). Since, as a muse, she would undoubtedly have been immortal, this is possible, though unsavoury.

The Emperor Hadrian tried to untangle these contradictory accounts by asking the Pythian Sibyl for her tuppence, and was told, ‘Ithaca is his country, Telemachus his father, and Epicasta, daughter of Nestor, the mother that bore him, a man by far the wisest of mortals.’ If she was correct, and Telemachus, the son of Odysseus, was Homer’s sire, The Odyssey becomes a biography of his grandfather as much as an epic poem.

At Chios, a group of later rhapsodes announced themselves as the Homeridae, or the sons of Homer, who solemnly learned, recited and preserved the works of the Poet. Were there literal as well as figurative offspring? Tzetzes mentions that a poem called The Cypria, dealing with the prequel to the Trojan War and attributed to one Stasinus, was for the most part written by Homer, and given to the poet Stasinus, along with money, as part of a dowry. One presumes that this means that Homer had a daughter. The Cypria, however, was also sometimes thought to be the work of Hegesias of Troezen; little of it survives, and it is thus impossible to confirm the conjectural daughter.

Accounts agree, however, on one important feature. The Poet was blind. The birthplace claim of Smyrna is bolstered by the contention that homer, in their dialect, means ‘blind’ (though not, as in the description of the Cyclops, in The Odyssey). A section in the Hymn to Delian Apollo is taken, by vague tradition, to be a self-description of Homer – or Melesigenes, as he was called before the Smyrnans christened him ‘Blindy’:

‘Whom think ye, girls, is the sweetest singer that comes here, and in whom do you most delight?’ Then answer, each and all, with one voice: ‘He is a blind man, and dwells in rocky Chios: his lays are evermore supreme.’ As for me, I will carry your renown as far as I roam over the earth to the well-placed this thing is true.

It seems that, rather than being born sightless, Homer went blind: cataracts, diabetic glaucoma, infection by the nematode toxocara. The later poet Stesichorus was struck blind by the gods for slandering Helen, and only had his sight miraculously restored when he rewrote his work, insisting that Helen had not eloped. Instead, she had been spirited away to Egypt and replaced with a phantom fashioned of clouds. Stesichorus blamed Homer, and Homer’s version of events, for his temporary loss of sight. Presumably Homer’s blindness was occasioned by a similar infraction. If, after The Iliad, he was struck blind, then the blinding of Polyphemus the Cyclops in The Odyssey must supposedly be drawn from personal experience.

The place of Homer’s death, thankfully, is barely in dispute: the island of Ios. Indeed, Homer himself was informed by a Pythian Sibyl that he would die on Ios, after hearing a children’s riddle. She referred to the island as the homeplace of his mother (but Nestor’s daughter came from Pylos, a good 150 miles away! One of the priestesses must be mistaken). Eventually Homer went to Ios, to stay with Creophylus. What qualities or creature comforts this Creophylus possessed that would make the bard travel to exactly the place where he had been warned that he would die must be left to the imagination. On the beach he met with some children who had been fishing. When he asked them if they had caught anything, they replied, ‘All that we caught we left behind and we are carrying all that we did not catch.’ Nonplussed, he asked for an explanation, and was rewarded with the information that they were talking about their fleas. Suddenly remembering the oracle and its dire warning about riddling kids, Homer composed his epitaph, and died three days later.

At least we have the texts; the 27,803 lines that are ‘Homer’. But even these are susceptible to error. Despite the best efforts of the Homeridae, the texts were unstable, misremembered, interpolated. The librarians of Alexandria, Zenodotus, Aristophanes of Byzantium and Aristarchus, all later endeavoured to fix the text, to staunch the ebb of letters. The two poems were divided into books, each poem in twenty-four books, exactly the number of letters in the Greek alphabet. No other recorded epics had such an elegant numerology. Earlier, Aristotle himself prepared an edition for Alexander, who placed it in a jewel-encrusted golden casket despoiled from King Darius at the battle of Arbela, with the words: ‘But one thing in the world is worthy of so costly a repository.’ But opulent boxes cannot preserve, nor can locks and keys keep back, the depredations of error. Before any of these scholars tried to secure The Iliad and The Odyssey, less reverent hands had handled the manuscripts.

The sixth-century BCE Athenian tyrant Peisistratus was generally held to be an enlightened man, who reformed taxes and developed the Solonic legal systems. He was also a patron of the arts and the founder of the Dionysia festival; and he was concerned with establishing a standard text of the works of Homer. To this end, he employed a writer called Onomacritus, who undertook the task.

On the surface, Onomacritus seemed to be an ideal choice; he had, after all, already edited the poems and oracles of Musaeus. But, Herodotus informs us, there was a less professional side to the man. Lasus of Hermione, who is credited with teaching the lyric poet Pindar, had accused Onomacritus of misattribution, and even forgery, in his edition of Musaeus – brazenly importing his own words.

Onomacritus may have been acting under a direct political imperative to alter the text. Peisistratus had recently undertaken a military campaign and successfully captured the port of Salamis from the Megarans. After a halt in the offensive, the state of Sparta had agreed to arbitrate between Athens and Megara over the true ownership of Salamis, and the Athenians clinched their case by quoting Homer, specifically, verse 558 of Book II, which described Salamis as traditionally being an Athenian dominion. The Megarans, outraged, later accused the Athenians of a brazen fabrication.

So the preservation of the poems which occupy the apex of literary achievement in Europe was entrusted to someone of questionable integrity, on behalf of a tyrant with a vested interest about border disputes. Was Onomacritus so awed by his position that he carried out the work scrupulously? Or did the recidivist urge to tinker and tamper, meddle and fiddle get the better of him – did he improve the text? Is even part of Homer – the slightest line, the tiniest adjective – forged? The critic Zoilus was thrown over a cliff by irate Athenians who objected to his carping criticism of the divine Homer, his snags at odd words and niggles at images: would they have been so precipitate if he had questioned the phraseology of Onomacritus?

In addition to The Iliad, The Odyssey, scraps of The Cypria and the so-called Homeric Hymns, we learn of other epics composed by, or attributed to, Homer. In the pseudo-Herodotus’ Life of Homer, we hear of a poem entitled The Expedition of Amphiarus, composed in a tanner’s yard. The Taking of Oechalia was mentioned by Eustathius; it was given to Creophylus or was actually written by Creophylus. We have one line, which is, unfortunately, identical to line 343 of book XIV of The Odyssey. There was a Thebais, which recounted the fate of Oedipus and the Seven Champions’ attack on Thebes. It was 7,000 lines long and began: ‘Goddess, sing of parched Argos whence kings’, as well as its sequel, The Epigoni, when the seven sons of the Seven Champions finish the job. Again, the poem was in 7,000 lines, and began: ‘And now, Muses, let us begin to sing of men of later days’.

But most tantalizing of all is the Margites. In the fourth chapter of his Art of Poetry, Aristotle said:

Homer was the supreme poet in the serious style . . . he was the first to indicate the forms that comedy was to assume, for his Margites bears the same relationship to our comedies as his Iliad and Odyssey bear to our tragedies.

The Margites, it is claimed, was Homer’s first work. He began it while still a schoolteacher in Colophon (according to the Colophonians). The name of the hero, Margites, derives from the Greek , meaning madman. The Poet’s first work was a portrait of a fool.

Alexander Pope, who never quite got over not being Homer, explained further:

MARGITES was the name of this personage, whom Antiquity recordeth to have been Dunce the First; and surely from what we hear of him, not unworthy to be the root of so spreading a tree, and so numerous a posterity. The poem therefore celebrating him, was properly and absolutely a Dunciad; which tho’ now unhappily lost, yet is its nature sufficiently known by the infallible tokens aforesaid. And thus it doth appear, that the first Dunciad was the first Epic poem, written by Homer himself, and anterior even to the Iliad and the Odyssey.

This was reason enough for Pope to produce his own Dunciad, from the Preface to which the above words are taken.

Can we tell from the title what the book was about? The definition of madness is never fixed, but fluid, shaped by its culture and dependent on what is considered sane, reasonable or self-evident. A rational, scientifically minded Greek of the fifth century BCE could maintain that when a woman had a nosebleed, it meant her menstruation had got lost, that the Sun gave birth to maggots in dung and that a tribe of one-eyed men called the Arimaspi lived in the extreme North. Madness encompasses murderous rage and inappropriate levity, fearfulness and fearlessness, silence and babble. The title could suggest just about anything.

All that is left of Homer’s comic epic are a few lines, pickled in other works. The Scholiast, writing on Aeschines, gives a thumbnail sketch that fits with his etymologically unfortunate name: ‘Margites . . . a man, who, though fully grown, did not know if his mother or father had given birth to him, and who would not sleep with his wife, saying he was afraid she would give a bad account of him to his mother.’ At this point, Margites seems to coincide with Nietzsche’s description of the comedy of cruelty, as Schadenfreude. We laugh, because we know we are superior to poor Margites, for whom the birds and the bees are mysteries.

Plato and Aristotle each record a snippet of the poem. From Plato’s fragmentary Alcibiades we learn that ‘he knew many things, but all badly’. This Margites is a quack, a clown, a halfwit. It is not his innocence in a chaotic world that forms the comedy, but the chaos of his half-baked theories and half-assed ideas. Aristotle, in the Nicomachean Ethics, offers a different hint: ‘the gods taught him neither to dig nor to plough, nor any other skill; he failed in every craft.’ Odd. Odd indeed. Aristotle’s Margites is an idiot, he has no function, no social reason. He’s a spare part, an appendix. A vague imputation of laziness hangs over this creature who is confused by the difference between spades and hoes.

Is this a naive Stan or a flustering Ollie? Was he the stooge, the kid from the sticks, the fish out of water, the innocent abroad or the country cousin? Zenobius presents, again, an illustration. ‘The fox knows many a ruse, but the hedgehog’s single trick beats them all,’ a phrase also attributed to Archilochus. Is Margites the fox or the hedgehog? Nowhere in the extant extracts is there the sense that Margites is a cheat, a con or a wily individual. Zenobius suggests something else: the wise little man. Chaplin. Forrest Gump. Candide. The Good Soldier Schweik. Homer Simpson.

The Margites is not the only comic epic that existed. Arctinus of Miletus, the author of the lost War of the Titans and a continuation of The Iliad, may be the author of The Cercopes. The Suda records that:

these were two brothers living upon the earth who practised every kind of knavery. They were called Cercopes (or ‘The Monkey-Men’) because of their cunning doings: one of them was named Passalus and the other Acmon. Their mother, a daughter of Memnon, seeing their tricks, told them to keep clear of Black-bottom, that is, of Herakles. These Cercopes were sons of Theia and Ocean, and are said to have been turned to stone for trying to deceive Zeus. Liars and cheats, skilled in deeds irremediable, accomplished knaves. Far over the world they roamed deceiving men as they wandered continually.

This form of comedy seems subtly different from the Margites: this is a pair of rogues, a couple of tricksters. We know they came an inevitable cropper. A carved frieze depicts Herakles with the scallywags trussed up by their ankles, hanging upside down.

With The Cercopes the audience is permitted a double empathy: we can enjoy their shameless pranks and outrageous antics, as well as the satisfaction of seeing their eventual comeuppance. Where the sympathies lie with Margites is far less clear. The heroes of The Iliad and The Odyssey are far from perfect. Achilles is petulant and inhumane, Odysseus is untrustworthy and vengeful. But a flawed hero can nonetheless be a real hero – a flawed schmuck seems, frankly, unimaginable. What could we have learned if the Margites had been spared! Did the Greeks laugh at or with or in a wholly different preposition? Did they yearn, in a rebuke to their entrenched sophistication, for a fool who muddled through? Did they mock the afflicted or smirk at the affected?

Of all the lost books, the Margites is the least explicable, the most tantalizing. Its author was esteemed beyond measure. It was unique among his works. But perhaps – just perhaps – its loss should not be mourned too deeply. What is gone must be reinvented. In the absence of a comedy by the greatest poet of all time, successive generations have been free to imagine sarcastic, sentimental, whimsical, serious, gentle and black comedies, wit and smut, slapstick and riddle. An explosion of new forms may be worth one extinction.

Hesiod

(seventh century BCE)

Homer is only ever glimpsed in his work. At the opening of the Theogony, one of the two extant works attributed to the Boeotian poet Hesiod, the poet himself appears. Although the bulk of the poem is an elaborate catalogue of the genealogy of the gods, it opens with a scene describing how, on Mount Helicon, the Muses taught the shepherd Hesiod how to sing, swiftly shifting their address to the first-person poet. ‘They gave me a staff of blooming laurel,’ he says, and ‘breathed a sacred voice’ into him.

But scholars from the earliest days have wondered how much of the work attributed to Hesiod was actually written by him. Longinus was so offended by a line about the snot-nosed goddess Trouble that he thought fit to exonerate the actual Hesiod from being the author of the lost work from which the line came, the Shield of Herakles. Of the two poems we have, the Theogony and Works and Days, most contemporary scholars would like at least one to be by Hesiod.

So the appearance of Hesiod in the Theogony might be thought to clinch the case. But on grounds of style, diction and the fact that it is occasionally rather gauche and boring, translators and critics have been loath to believe it can be by the same author as Works and Days. Nonetheless, the Greeks thought they were written by one author, and we shall proceed as if Hesiod wrote both poems.

Works and Days is strikingly dissimilar to the Theogony. It begins with two origin myths that account for the state of mankind. Firstly, the reader is told about Pandora’s Box, and the unleashing of manifold pains, cares and diseases on humanity. Then we learn about Zeus’ fivefold attempts at creation: the Gold, Silver, Bronze, Heroic and Iron Races, of which, Hesiod gloomily informs us, he belongs to the ferrous species, and would rather have died sooner or not be born yet.

The later parts of the work offer agricultural maxims, interspersed with autobiographical asides, and the whole is cast as an epistle to his cheating brother Perses, who would do well to listen to some homespun advice. No one can argue with ‘Wrap up warm to prevent gooseflesh’ or ‘Invite your friends, not your enemies, to dinner’, though ‘Don’t piss facing the sun’ and ‘Never have sex after funerals’ seem more peculiar prohibitions.

The writer of Works and Days is not some autodidact, spinning his gripes and saws into a more mnemonic form. He tells us he won a poetry competition at the funeral games for King Amphidamas, and placed the prize (a tripod) on Mount Helicon, where he first started to write, on returning home. In Works and Days Hesiod does not tell us the title of his award-winning entry, and, since such works as The Precepts of Chiron, The Astronomy, The Marriage of Ceyx, Melampodia, Aegimius, Idaen Dactyls and The List of Heroines have all proven vulnerable to the corrosion of passing time, at least one academic has made a virtue of necessity and argued that Hesiod must have been reciting the Theogony.

But against whom was he vying in this competition? At the beginning of Works and Days, when surveying the effects of the goddess Strife, Hesiod conjectures that there must be two goddesses; since some forms of striving, such as warfare, are pernicious, and others, such as the healthy competition between tradesmen, farmers and even poets, are wholly beneficial. The ancients took this as a cue to link Hesiod (whoever he was) with the only other great early poet, Homer (whoever he was).

Another poem, called The Contest of Homer and Hesiod, is sometimes ascribed to Hesiod, even though the version that we have dates from nearly a millennium later. In it, Homer trounces Hesiod in every bout, and at one point seems to exasperate him into speaking nonsense. In the final round, they each read from ‘their’ greatest works: The Iliad and Works and Days. The judges eventually give the victory (surprise, surprise! It’s a tripod!) to Hesiod, since the man who praises peace is better than the man who glorifies war. Blatantly apocryphal and clearly anachronistic, it is still the story that would be most charming, if true.

The Yahwist, the Elohist, the Deuteronomist, the Priestly Author and the Redactor

(c. sixth century BCE)

The Bible is frequently described as a library rather than a book: it is also a mausoleum of writers, a vast graveyard of authors. Who wrote the Bible? The orthodox answer is, assuredly, God; but even the most inflexible traditionalist does not believe that the Infinite condescended to ink. Through prophecy, inspiration and occasionally blatant dictation, God speaks but Man writes. God does have books – in particular, one which He is inordinately fond of editing. As He says to Moses, ‘Whoever hath sinned against me, him will I blot out of my book.’ But the books of the Bible as we have them are by God by proxy at best.

With the books of prophecy, it seemed logical to assign them to the prophets themselves as nominal authors. We are exhorted to ‘Hear the Word of the Lord’, regurgitated through human agency, as in the case of Ezekiel, whom God forced to swallow a scroll containing His message. The prophets sometimes employed their God’s method of production: Jeremiah entrusted the actual transcription of his prophecies, which threatened the impending Babylonian conquest, to Baruch, who had to make multiple copies since the King, Jehoiakim, kept on burning the offending prophecies.

Jeremiah raged against false prophets, who were predicting an opposite outcome. Naturally enough, when Babylon did conquer Israel, the words of the worthless prophets were lost, and the correct foretellings of Jeremiah acquired the authenticity of oracular revelation. The scribes who collected the prophets were not above sleight of hand in this matter: the Book of Isaiah collates the words of an eighth-century BCE prophet with the words of another, unknown prophet who lived two centuries after Isaiah’s death. Hindsight makes exceptionally good foresight.

Then there are the five first books, the Pentateuch, which contain the laws given to Moses and the prehistorical origin of the world. Tradition ascribed these books to Moses himself, which seems unlikely, given that they also contain an account of Moses’ death, and his burial by God, ‘no man knows where’.

Though apologists and ideologues are keen to present the scriptural texts as a unity (the Gideon Bible, for example, refers to the authors from different eras and backgrounds who nonetheless ‘perfectly agree on doctrine’), the Bible is riddled with snags and stray threads. In particular, we can investigate the books in the Bible, rather than the books of it. King Solomon, for example, ‘spake three thousand proverbs: and his songs were a thousand and five’. There are 1,175 verses in the Book of Proverbs, and only one ‘Song of Songs’. Even in cataloguing the accomplishments of the ruler, the Bible also reveals the extent to which his achievements are lost.

Likewise, we have no idea what became of the ‘book in seven parts’ commissioned by Joshua, which described the cities that would be divided amongst the Israelites. Nor do we have the Book of Jasher, cited twice, and which, presumably, contained material on King David’s archery lessons and the stilling of the sun in the valley of Ajalon. The ‘Book of the Battles of Yahweh’, mentioned in the Book of Numbers, chapter 21, is likewise lost. Throughout the First and Second Book of Kings and the First and Second Book of Chronicles, the writer refers the reader to the ‘Book of the Chronicles of the Kings of Israel’ and the ‘Book of the Chronicles of the Kings of Judah’, neither of which invaluable resource has survived.

In the Apocrypha, we learn that the Book of the Maccabees is a summary of the more complete, five-volume work by Jason of Cyrene. The Apocrypha also contains an account of the creation of the scriptures. ‘For thy law is burnt, therefore no man knoweth the things that are done of thee, or the works that shall begin,’ complains Esdras, and in response God commands him to recite the 204 books containing the Law, which are transcribed by five scholars over a period of forty days. The final seventy, the ‘Books of Mystery’, are held back from the people: still, it leaves ninety-five whole volumes unaccounted for.

The Bible appears again in its own history. In the Second Book of Kings, King Josiah intends to reconsecrate and refurbish the Temple in 621 BCE, after its desecration by the Baal-worshipping sons of Athaliah. Hilkiah, the High Priest, is told to reckon up the amount of silver they have; and, in doing so, stumbles on the long-lost Book of the Law. With Shaphan the Scribe, they show it to the young King, who rends his garments on hearing of what will happen to those who do not follow in the paths of righteousness. Saint Jerome and Saint John Chrysostom in the fourth century CE both identified this Book of the Law with the Book of Deuteronomy. Josiah instructs them to seek out Huldah the Prophetess, to explain the work in detail. She confirms that if the King rectifies the behaviour of the people, God’s anger will be deflected. Though Joash is told that God will ‘gather him into his grave in peace’, the Second Book of Chronicles claims he is murdered by his people, suffering from great diseases, after a Syrian incursion. The whole story of Hilkiah, Shaphan and Huldah is omitted from Chronicles. It is not the only, or most bizarre, contradiction between the pseudo-historical accounts; compare, for example, 2 Samuel 24:1 (‘And again the anger of the LORD was kindled against Israel, and he moved David against them to say, Go, number Israel and Judah’) with 1 Chronicles 21:1 (‘And Satan stood up against Israel, and provoked David to number Israel’).

Though the epithet ‘People of the Book’ was conferred on all the followers of the first Abrahamic religions, it appears that in the histories and prophecies we are more likely to encounter lost books, burned manuscripts and secret scrolls. Then, in the nineteenth century, a shocking new perspective on the question ‘Who wrote the Bible?’ was found.

The so-called ‘Documentary Hypothesis’ is an exercise in pure stylistics. We may not be able to know the names of the biblical authors, but, as Jean Astruc first demonstrated in 1753, we can trace their signatures and idiosyncratic constructions throughout the individual books. In effect, the Bible’s text can bring us back to its putative authors.

The theory stems from a cluster of inconsistencies in the Book of Genesis. At times, God is referred to as ‘Yahweh’, and at others, as ‘Elohim’. Moreover, in chapters 1 and 2, the same event – the Creation of Adam and Eve – is narrated twice; at Genesis 1:26–7 and at Genesis 2:7, 21–3. In chapter 1, we are told ‘God created man in his own image, in the image of God created he him; male and female created he them’. In chapter 2, we are told of Adam being fashioned out of dust and breath, and Eve from Adam’s rib. There are further curious anomalies. In chapter 1, God makes the birds and sea-creatures on the fifth day, and the land animals on the sixth, prior to Adam. In chapter 2, verse 19, God creates animals after Adam.

The Documentary Hypothesis suggests that there were originally two Books of Genesis, one by ‘J’ – the Yahwist, the writer who calls God ‘Yahweh’ – and another by ‘E’ – the Elohist, who refers to ‘Elohim’. These ‘ur-texts’ were synthesized into one version, with both contradictory sections aspicked together. ‘J’, for example, is fond of puns: it is to him that the etymology of ‘Adam’, meaning red earth, belongs. ‘J’ also is keen to give explanations for how things came about and why names are attached to particular places. ‘E’ is altogether more cryptic, an older version, perhaps especially considering his name for God is unaccountably in the plural.

To ‘J’ and ‘E’ were added the Deuteronomist (‘D’) and the Priestly Author (‘P’). ‘D’ had a clear ideological theology; that God punished Israel for its intransigence and for straying from the Law, and that the history of the Jewish people was a moral lesson in the consequences of disobedience. The Priestly Author was liturgist and ecclesiast, defining the ramification of the Law, the categories of clean and unclean, the role of the Levites and the authority of the Torah. ‘D’ understood the reasons for the Exile; ‘P’ reaffirmed the centrality of the Temple.

It’s a neat quartet, and an attractive theory. Unfortunately, it is only a theory. As much as one can almost hallucinate the differing qualities of ‘D’, ‘E’, ‘J’ and ‘P’, they are virtual authors at best, makeshift theories of possible writers. All of them collapse, especially at the advance of the fifth single-letter function: enter ‘R’, the Redactor.

‘R’ was the genius who spliced together ‘J’ and ‘E’ to give us the Old Testament. Only, ‘R’ was never singular; ‘R’ is a veritable host of textual editors, a dynasty of tinkerers, eliders, alterers, correctors, amenders and tidiers. Redactor, from the Latin redigere, redactum