6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

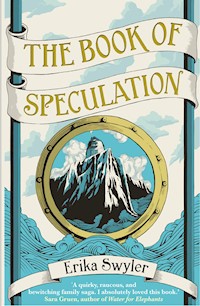

- Herausgeber: Corvus

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

For fans of The Night Circus, comes a sweeping and captivating debut novel about a young librarian who discovers that his family labours under a terrible curse. Simon Watson lives alone on the Long Island Sound. On a day in late June, Simon receives a mysterious book connected to his family. The book tells the story of two doomed lovers, two hundred years ago. He is fascinated, yet as he reads Simon becomes increasingly unnerved. Why do so many women in his family drown on 24th July? And could his beloved sister risk the same terrible fate? As 24th July draws ever closer, Simon must unlock the mysteries of the book, and decode his family history, before it's too late.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

About the Author

Erika Swyler, a graduate of New York University, is a writer and playwright whose work has appeared in literary journals and anthologies. Born and raised on Long Island’s north shore, Erika learned to swim before she could walk, and happily spent all her money at travelling carnivals. She is also a baker and photographer.

The Book of Speculation

Erika Swyler

with illustrations by the author

ATLANTIC BOOKS

London

Copyright page

First published in the United States in 2015 by St. Martin’s Press.

First published in export trade paperback and e-book in 2015 by Corvus, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

First published in hardback in 2016 in Great Britain by Corvus, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Erika Swyler, 2015

The moral right of Erika Swyler to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Australian ISBN: 978 1 78239 775 5

Hardback ISBN: 978 1 78239 776 2

Trade paperback ISBN: 978 1 78239 763 2

E-book ISBN: 978 1 78239 765 6

Printed in Great Britain.

Corvus

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

Dedication

For Mom. There are no words.

Contents

Acknowledgments

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Acknowledgments

Books have an awful lot of working parts; what follows are the essentials.

My agent, Michelle Brower, fixed a mess and didn’t flinch when I said I intended to hand bind the manuscripts myself. Before giving me good news, she advised me to sit down. She was correct in all things.

My editor, Hope Dellon, steered the book and me with such gentle cheer. She and St. Martin’s Press have been nothing short of fantastic.

Much of this book was written in the Comsewogue and Brooklyn Public Libraries. Circus history is wild and hairy, and an excellent reason to work in a library. When unable to invent towns, I relied on the historical societies of Charlotte, North Carolina; New Castle, Delaware; and Burlington, New Jersey. Any faults are mine.

A long list of names should go here, but there are too many. This book would not be were it not for Rick Rofihe and Matt de la Peña. Stephanie Friedberg called in the middle of the night to yell a chapter number at me, letting me know I was on to something. Karen Swyler was instrumental in the way only a sibling can be. Finally, Robert. Out of all the endless coffee, you are the best cup.

Chapter 1

June 20th

Perched on the bluff’s edge, the house is in danger. Last night’s storm tore land and churned water, littering the beach with bottles, seaweed, and horseshoe crab carapaces. The place where I’ve spent my entire life is unlikely to survive the fall storm season. The Long Island Sound is peppered with the remains of homes and lifetimes, all ground to sand in its greedy maw. It is a hunger.

Measures that should have been taken—bulkheads, terracing—weren’t. My father’s apathy left me to inherit an unfixable problem, one too costly for a librarian in Napawset. But we librarians are known for being resourceful.

I walk toward the wooden stairs that sprawl down the cliff and lean into the sand. I’ve been delinquent in breaking in my calluses this year and my feet hurt where stones chew at them. On the north shore few things are more essential than hard feet. My sister, Enola, and I used to run shoe-less in the summers until the pavement got so hot our toes sank into the tar. Outsiders can’t walk these shores.

At the bottom of the steps Frank McAvoy waves to me before turning his gaze to the cliff. He has a skiff with him, a beautiful vessel that looks as if it’s been carved from a single piece of wood. Frank is a boatwright and a good man who has known my family since before I was born. When he smiles his face breaks into the splotchy weathered lines of an Irishman with too many years in the sun. His eyebrows curl upward and disappear beneath the brim of an aging canvas hat he’s never without. Had my father lived into his sixties he might have looked like Frank, with the same yellowed teeth, the reddish freckles.

To look at Frank is to remember me, young, crawling among wood set up for a bonfire, and his huge hand pulling me away from a toppling log. He summons memories of my father poised over a barbecue, grilling corn—the smell of charred husk and burning silk—while Frank regaled us with fishing stories. Frank lied hugely, obviously. My mother and his wife egged him on, their laughter frightening the gulls. Two people are now missing from the tableau. I look at Frank and see my parents; I imagine it’s impossible for him to look at me and not see his departed friends.

“Looks like the storm hit you hard, Simon,” he says.

“I know. I lost five feet.” Five feet is an underestimate.

“I told your dad that he needed to get on that bulkhead, put in trees.” The McAvoy property lies a few hundred yards west of my house, farther back from the water with a terraced and planted bluff that’s designed to save Frank’s house come hell or, literally, high water.

“Dad was never big on listening.”

“No, he wasn’t. Still, a patch or two on that bulkhead could have saved you a world of trouble.”

“You know what he was like.” The silence, the resignation.

Frank sucks air through his teeth, making a dry whistling sound. “I guess he thought he had more time to fix things.”

“Probably,” I say. Who knows what my father thought?

“The water’s been coming up high the last couple years, though.”

“I know. I can’t let it go much longer. If you’ve got somebody you trust, I’d appreciate the name of a contractor.”

“Absolutely. I can send someone your way.” He scratches the back of his neck. “I won’t lie, though, it won’t be cheap.”

“Nothing is anymore, is it?”

“No, I suppose not.”

“I may wind up having to sell.”

“I’d hate to see you do that.” Frank’s brow furrows, tugging his hat down.

“The property is worth something even if the house goes.”

“Think on it some.”

Frank knows my financial constraints. His daughter, Alice, also works at the library. Redheaded and pretty, Alice has her father’s smile and a way with kids. She’s better with people than I am, which is why she handles programming and I’m in reference. But we’re not here about Alice, or the perilous state of my house. We’re here to do what we’ve done for over a decade, setting buoys to cordon off a swimming area. The storm was strong enough to pull the buoys and their anchors ashore, leaving them a heap of rusted chains and orange rope braid, alive with barnacles. It’s little wonder I lost land.

“Shall we?” I ask.

“Might as well. Day’s not getting any younger.”

I strip off my shirt, heft the chains and ropes over a shoulder, and begin the slow walk into the water.

“Sure you don’t need a hand?” Frank asks. The skiff scrapes against the sand as he pushes it into the water.

“No thanks, I’ve got it.” I could do it by myself, but it’s safer to have Frank follow me. He isn’t really here for me; he’s here for the same reason I do this walk every year: to remember my mother, Paulina, who drowned in this water.

The Sound is icy for June, but once in I am whole and my feet curl around algae-covered rocks as if made to fit them. The anchor chains slow me, but Frank keeps pace, circling the oars. I walk until the water reaches my chest, then neck. Just before dipping under I exhale everything, then breathe in, like my mother taught

me on a warm morning in late July, like I taught my sister.

The trick to holding your breath is to be thirsty.

“Out in a quick hard breath,” my mother said, her voice soft just by my ear. In the shallow water her thick black hair flowed around us in rivers. I was five years old. She pressed my stomach until muscle sucked in, navel almost touching spine. She pushed hard, sharp fingernails pricking. “Now in, fast. Quick, quick, quick. Spread your ribs wide. Think wide.” She breathed and her rib cage expanded, bird-thin bones splayed until her stomach was barrel-round. Her bathing suit was a bright white glare in the water. I squinted to watch it. She thumped a finger against my sternum. Tap. Tap. Tap. “You’re breathing up, Simon. If you breathe up you’ll drown. Up cuts off the space in your belly.” A gentle touch. A little smile. My mother said to imagine you’re thirsty, dried out and empty, and then drink the air. Stretch your bones and drink wide and deep. Once my stomach rounded to a fat drum she whispered, “Wonderful, wonderful. Now, we go under.”

Now, I go under. Soft rays filter down around the shadow of Frank’s boat. I hear her sometimes, drifting through the water, and glimpse her now and then, behind curtains of seaweed, black hair mingling with kelp.

My breath fractures into a fine mist over my skin.

Paulina, my mother, was a circus and carnival performer, fortune-teller, magician’s assistant, and mermaid who made her living by holding her breath. She taught me to swim like a fish, and she made my father smile. She disappeared often. She would quit jobs or work two and three at once. She stayed in hotels just to try out other beds. My father, Daniel, was a machinist and her constant. He was at the house, smiling, waiting for her to return, waiting for her to call him darling.

Simon, darling. She called me that as well.

I was seven years old the day she walked into the water. I’ve tried to forget, but it’s become my fondest memory of her. She left us in the morning after making breakfast. Hard-boiled eggs that had to be cracked on the side of a plate and peeled with fingernails, getting bits of shell underneath them. I cracked and peeled my sister’s egg, cutting it into slivers for her toddler fingers. Dry toast and orange juice to accompany. The early hours of summer make shadows darker, faces fairer, and hollows all the more angular. Paulina was a beauty that morning, swanlike, someone who did not fit. Dad was at work at the plant. She was alone with us, watching, nodding as I cut Enola’s egg.

“You’re a good big brother, Simon. Look out for Enola. She’ll want to run off on you. Promise you won’t let her.”

“I won’t.”

“You’re a wonderful boy, aren’t you? I never expected that. I didn’t expect you at all.”

The pendulum on the cuckoo clock ticked back and forth. She tapped a heel on the linoleum, keeping quiet time. Enola covered herself with egg and crumbs. I battled to eat and keep my sister clean.

After a while my mother stood and smoothed the front of her yellow summer skirt. “I’ll see you later, Simon. Goodbye, Enola.”

She kissed Enola’s cheek and pressed her lips to the top of my head. She waved goodbye, smiled, and left for what I thought was work. How could I have known that goodbye meant goodbye? Hard thoughts are held in small words. When she looked at me that morning, she knew I would take care of Enola. She knew we could not follow. It was the only time she could go.

Not long after, while Alice McAvoy and I raced cars across her living room rug, my mother drowned herself in the Sound.

I lean into the water, pushing with my chest, digging in my toes. A few more feet and I drop an anchor with a muffled clang. I look at the boat’s shadow. Frank is anxious. The oars slap the surface. What must it be like to breathe water? I imagine my mother’s contorted face, but keep walking until I can set the other anchor, and then empty the air from my lungs and tread toward the shore, trying to stay on the bottom for as long as possible—a game Enola and I used to play. I swim only when it’s too difficult to maintain the balance to walk, then my arms move in steady strokes, cutting the Sound like one of Frank’s boats. When the water is just deep enough to cover my head, I touch back down to the bottom. What I do next is for Frank’s benefit.

“Slowly, Simon,” my mother told me. “Keep your eyes open, even when it stings. It hurts more coming out than going in, but keep them open. No blinking.” Salt burns but she never blinked, not in the water, not when the air first hit her eyes. She was moving sculpture. “Don’t breathe, not even when your nose is above. Breathe too quickly and you get a mouthful of salt. Wait,” she said, holding the word out like a promise. “Wait until your mouth breaks the water, but breathe through your nose, or it looks like you’re tired. You can never be tired. Then you smile.” Though small-mouthed and thin-lipped, her smile stretched as wide as the water. She showed me how to bow properly: arms high, chest out, a crane taking flight. “Crowds love very small people and very tall ones. Don’t bend at the waist like an actor; it cuts you off. Let them think you’re taller than you are.” She smiled at me around her raised arms, “And you’re going to be very tall, Simon.” A tight nod to an invisible audience. “Be gracious, too. Always gracious.”

I don’t bow, not for Frank. The last time I bowed was when I taught Enola and the salt stung our eyes so badly we looked like we’d been fighting. Still, I smile and take in a deep breath through my nose, let my ribs stretch and fill my gut.

“Thought I was going to have to go in after you,” Frank calls.

“How long was I down?”

He eyes his watch with its cracked leather strap and expels a breath. “Nine minutes.”

“Mom could do eleven.” I shake the water from my hair, thumping twice to get it out of my ear.

“Never understood it,” Frank mutters as he frees the oars from the locks. They clatter when he tosses them inside the skiff. There’s a question neither of us asks: how long would it take for a breath-holder to drown?

When I throw on my shirt it’s full of sand; a consequence of shore living, it’s always in the hair, under the toenails, in the folds of the sheets.

Frank comes up behind me, puffing from dragging the boat.

“You should have let me help you with that.”

He slaps my back. “If I don’t push myself now and again I’ll just get old.”

We make small talk about things at the marina. He complains about the prevalence of fiberglass boats, we both wax poetic about Windmill, the racing sail he’d shared with my father. After Mom drowned, Dad sold the boat without explanation. It was cruel of him to do that to Frank, but I suppose Frank could have bought it outright if he’d wanted. We avoid talking about the house, though it’s clear he’s upset over the idea of selling it. I’d rather not sell either. Instead we exchange pleasantries about Alice. I say I’m keeping an eye out for her, though it’s unnecessary.

“How’s that sister of yours? She settled anywhere yet?”

“Not that I know of. To be honest, I don’t know if she ever will.”

Frank smiles a little. We both think it: Enola is restless like my mother.

“Still reading tarot cards?” he asks.

“She’s getting by.” She’s taken up with a carnival. Once that’s said, we’ve ticked off the requisite conversational boxes. We dry off and heft the skiff back up on the bulkhead.

“Are you heading up?” I ask. “I’ll walk back with you.”

“It’s a nice day,” he says. “Think I’ll stay down here awhile.” The ritual is done. We part ways once we’ve drowned our ghosts.

I take the steps back, avoiding the poison ivy that grows over the railings and runs rampant over the bluff—no one pulls it out; anything that anchors the sand is worth whatever evil it brings— and cut through the beach grass, toward home. Like many Napawset houses, mine is a true colonial, built in the late 1700s. A plaque from the historical society hung beside the front door until it blew away in a nor’easter a few years back. The Timothy Wabash house. With peeling white paint, four crooked windows, and a sloping step, the house’s appearance marks prolonged negligence and a serious lack of funds.

On the faded green front step (have to get to that) a package props open the screen door. The deliveryman always leaves the door open though I’ve left countless notes not to; the last thing I need is to rehang a door on a house that hasn’t been square since the day it was built. I haven’t ordered anything and can’t think of anyone who would send me something. Enola is rarely in one place long enough to mail more than a postcard. Even then they’re usually blank.

The package is heavy, awkward, and addressed with the spidery scrawl of an elderly person—a style I’m familiar with, as the library’s patrons are by and large an aging group. That reminds me, I need to talk to Janice about finding stretchable dollars in the library budget. Things might not be too bad if I can get a patch on the bulkhead. It wouldn’t be a raise, a one-time bonus maybe, for years of service. The sender is no one I know, an M. Churchwarry in Iowa. I clear a stack of papers from the desk—a few articles on circus and carnivals, things I’ve collected over the years to keep abreast of my sister’s life.

The box contains a good-sized book, carefully wrapped. Even before opening it, the musty, slightly acrid scent indicates old paper, wood, leather, and glue. It’s enveloped in tissue and newsprint, and unwrapping reveals a dark leather binding covered with what would be intricate scrollwork had it not suffered substantial water damage. A small shock runs through me. It’s very old, not a book to be handled with naked fingers, but seeing as it’s already ruined, I give in to the quiet thrill of touching something with history. The edges of the undamaged paper are soft, gritty. The library’s whaling collection lets me dabble in archival work and restoration, enough to say that the book feels to be at least from the 1800s. This is appointment reading, not a book you ship without warning. I shuffle my papers into two small stacks to support the volume—a poor substitute for the bookstands it deserves, but they’ll do.

A letter is tucked inside the front cover, written in watery ink with the same shaky hand.

Dear Mr. Watson,

I came across this book at auction as part of a larger lot I purchased on speculation. The damage renders it useless to me, but a name inside it —Verona Bonn—led me to believe it might be of interest to you or your family. It’s a lovely book, and I hope that it finds a good home with you. Please don’t hesitate to contact me if you have any questions that you feel I may be able to answer.

It is signed by a Mr. Martin Churchwarry of Churchwarry & Son and includes a telephone number. A bookseller, specializing in used and antiquarian books.

Verona Bonn. What my grandmother’s name would be doing inside this book is beyond me. A traveling performer like my mother, she would have had no place in her life for a book like this. With the edge of my finger, I turn a page. The paper nearly crackles with the effort. Must remember to grab gloves along with book stands. The inside page is filled with elaborate writing, an excessively ornamented copperplate with whimsical flourishes that make it barely legible. It appears to be an accounting book or journal of a Mr. Hermelius Peabody, related to something containing the words portable and miracle. Any other identifiers are obscured by water damage and Mr. Peabody’s devotion to calligraphy. Skimming reveals sketches of women and men, buildings, and fanciful curved-roof wagons, all in brown. I never knew my grandmother. She passed away when my mother was a child, and my mother never spoke about her much. How this book connects to my grandmother is unclear, but it’s interesting nonetheless.

I dial the number, ignoring the stutter indicating a message. It rings for an exceedingly long time before an answering machine picks up and a man’s weathered voice states that I’ve reached Churchwarry & Son Booksellers and instructs to leave the time and date in addition to a detailed message as to any specific volume I’m seeking. The handwriting didn’t lie. This is an old man.

“Mr. Churchwarry, this is Simon Watson. I received a book from you. I’m not sure why you sent it, but I’m curious. It’s June twentieth, just six o’clock. It’s a fantastic specimen and I’d love to know more about it.” I leave multiple numbers, cell, home, and library.

Across the street, Frank heads toward his workshop, a barn to the side of his property. A piece of wood tucked under his arm, a jig of some sort. I should have asked him for money, not a contractor. Workmen I can probably find, the money to do the work is an entirely different matter. I need a raise. Or a different job. Or both.

A blinking light catches my eye. Voice mail. Right. I punch in the numbers. The voice at the other end is not one I expect to hear.

“Hey, it’s me. Shit. Do I call enough to be an it’s me? I hope you have an it’s me. That would be good. Anyway, it’s me, Enola. I’m giving you a heads-up. I’m coming home in July. It would be good to see you, if you feel like being around. Actually, I want you to be around. So, I’m coming home in July, so you should be home. Okay? Bye.”

I play it back again. She doesn’t call enough to be an it’s me. There’s noise in the background, people talking, laughing, maybe even the sound of a carnival ride or two, but I might be imagining that. No dates, no number, just July. Enola doesn’t work on a normal timeline; to her, leaving a month’s window is reasonable. It’s good to hear her voice, but also concerning. Enola hasn’t called in more than two months and hasn’t been home in six years, not since announcing that if she spent one more day in this house with me she’d die. It was a typical thing to say, but different in that we both knew she meant it, different because I’d spent the previous four years taking care of her after Dad died. Since then she’s called from time to time, leaving rambling messages. Our conversations are brief and centered on needs. Two years ago she called, sick with the flu. I found her in a hotel in New Jersey, hugging a toilet. I stayed three days. She refused to come home.

She wants to visit. She can. I haven’t touched her room since she left, hoping she’d come back, I suppose. I’d thought about turning it into a library, but there were always more immediate concerns, patching leaks, fixing electrical problems, replacing windows. Re-purposing my long-gone sister’s room wasn’t a priority. Though perhaps it’s convenient to think so.

The book sits by the phone, a tempting little mystery. I won’t sleep tonight; I often don’t. I’ll be up, fixating. On the house, on my sister, on money. I trace the curve of a flourished H with my thumb. If this book is meant for me, best find out why.

Chapter 2

The boy was born a bastard on a small tobacco farm in the rich-soiled Virginia hills. Had his birth been noted, it would have been in the 1780s, after a tobacco man could set his price for a hogshead barrel, but before he was swallowed up by all-consuming cotton. Little more than clapboard, his diminutive home was moss tipped and permanently shuttered against rain, flies, and the ever-present tang of tobacco from the drying shed.

His mother was the farmer’s wife, strong-backed Eunice Oliver. His father was Lemuel Atkinson, an attractive young man and proprietor of a traveling medicine show. With little more than a soft endearment and the lure of a gentleman’s supple hands, Eunice gained three bottles of Atkinson’s Elixir and a pregnancy.

The farmer, William Oliver, had three children to his name already and did not look kindly upon a bastard. Once the boy was up, walking, and too large to survive on table scraps, Mr. Oliver led the child into the heart of the woods and left him to fate. Eunice cried mightily at having her son taken, but the boy remained silent. The boy’s great misfortune was not that he was a bastard, but that he was mute.

He survived several years without words to explain them. In light the boy was hungry and fed himself however he could, picking berries with dirt-crusted hands; when he happened upon a farm, he stole from it on silent feet. A meat-drying house meant a night’s shelter and weeks of food. In dark he slept wherever there was warmth. His days shrank, becoming only fog, mountains, and a thick of trees so full the world itself fell in. The boy disappeared into this place, and it was here that he first learned to vanish.

People may live for a century without discovering the secret of vanishing. The boy found it because he was free to listen to the ground humming, the subtle moving of soil, and the breathing of water—a whisper barely discernible over the sound of a heartbeat. Water was the key. If he listened to its depth and measure and matched his breath to it, slowing his heart until it barely thumped, his slight brown frame would fade into the surrounding world. Had any watched, they would have seen a grubby boy turn sideways and vanish into the trees, becoming like a grain of sand—impossible to differentiate from the larger shore. Hunger, his enduring companion, was all that kept him certain that he lived.

Vanishing eased his survival, enabling him to walk into smokehouses and eat until heat and fumes drove him out. He snatched bread from tables, clothing from trees and bushes where it dried, and stole whatever he could to quiet his body’s demands.

Only once did he venture to the home that had abandoned him, when his memories of it had grown so vague he thought them imagined. He happened upon the gray house with the slanted roof and was shocked to find it real and not a remnant of a dream. He lifted the latch on a shutter just enough to peer through with a deep brown eye. This vantage showed the interior of a bedroom lit by what moonlight the ill-fitting shutters allowed.

A man and a woman slept on a straw mattress. The boy looked at the man’s rough features, the stiff dark bristles jutting from his chin, and felt nothing. The woman lay on her side, brown hair spilling across the edge of her smock. Something woke in the boy, a flash of that hair brushing the back of his hand. He crept into the house, past a long table and the bed of a sleeping child, and slipped into the room where the woman and the man slept, his body remembering the way as though it had traveled it thousands of times. He gently lifted the bedsheet, slid beneath, and closed his eyes. The woman’s smell was at once familiar, lye soap and curing tobacco, a scent that lived deep inside him that he’d forgotten. Her warmth made his chest stammer.

He fled before she woke.

He didn’t see the woman rouse the man or hear her tell the man that she’d had the sensation of being watched, or that she’d dreamt of her son. The boy did not return to the house. He walked back into the woods, searching for other shelter, other food, and places that didn’t make his skin burn.

On the banks of the muddy Dan River, not far from Boyd’s Ferry, was the town of Catspaw, named for the shape of the valley in which it lay; it was colored the ochre of the river’s loam and dusty with the tracks of horses and mules. The freshets that plagued Boyd’s Ferry would later cause Catspaw to melt back into the hills, but at the time the settlement was burgeoning. The boy traveled the Dan’s winding edge until he stumbled upon the town. It was frightening but filled with potential; washerwomen boiled large tubs of clothing, sloshing soap and wash water down to the river, men poled flat boats, and horses pulled wagons along the banks and up through the streets, each carrying women and men. The cacophonous jumble of water, people, and wagons terrified the boy. His eyes darted until they latched onto a woman’s bright blue dress and watched as the heavy cloth swung back and forth. He hid behind a tree, covered his ears, and tried to slow his heartbeat, to listen to the breath of the river.

Then—a wondrous sound.

Heralded by a glorious voice, a troupe of traveling entertainers arrived. A mismatched collection of jugglers, acrobats, fortune-tellers, contortionists, and animals, the band was presided over by Hermelius H. Peabody, self-proclaimed visionary in entertainment and education, who thought the performers and animals (a counting pig deemed learned, a horse of miniature proportions, and a spitting llama) were instruments for improving minds and fattening his purse. On better days Peabody fancied himself professorial, on worse days townsfolk were unreceptive to enlightenment and ran him out of town. The pig wagon, with its freshly painted blue sides proudly declaring the animal’s name, “Toby,” bore scars from unfortunate run-ins with pitchforks.

The boy watched townspeople crowd a green and gold wagon as it rolled into the open central square. Close behind were several duller carts and carriages, some with round tops fashioned from large casks, painted every color in creation, each carrying a hodgepodge of people and animals. The wagons circled and women pulled children to their skirts to keep them from running too close to the wheels. The lead wagon was painted with writing so ornate it was near indecipherable; on it stood an impressive man in flamboyant attire—Peabody. Accustomed to lone traveling jugglers or musicians, the townsfolk had not encountered such a spectacle before.

Never had there been such a man as Hermelius Peabody and he was fond of saying so. Both his height and appearance commanded attention. His beard came to a twisted point that brushed his chest and pristine white hair hung to his shoulders, topped by a curly hat that flirted with disintegration; that it held together at all appeared an act of trickery. His belly blatantly taunted gravity; riding high and round, it dared his waistcoat’s brass buttons to contain it and strained his red velvet jacket to its limit. Yet the most remarkable thing about Hermelius Peabody was his voice, resonating through the valley with a rich rumbling that grew from deep within his stomach.

“Ladies and gentlemen, you are indeed fortuitous!” He motioned to a lean man behind him. The man, who had a thick scar that tugged at the corner of his mouth, whispered into Peabody’s ear. “Virginians,” Peabody shouted. “Before you is the most amazing spectacle you shall ever see. From the East I bring you the greatest Orient contortionist!” A willowy girl scrambled onto a carriage roof, tucked a leg behind her head, and tipped forward to stand on one hand.

The boy was transfixed. He inched from behind his tree.

“From the heart of the Carpathians,” Peabody shouted and lifted his arms to the sky, “shrouded in the depths of Slavic mysticism, raised by wolves and schooled in the ancient arts of fortune-telling, The Madame Ryzhkova.” The crowd murmured as a stooped woman wrapped in a broadloom’s worth of silk emerged from a curved-top wagon and extended a twisted hand.

Peabody’s voice resonated with the wild part of the boy, crooning and soothing. He inched toward the spectators, toward the wagons, snaking between bodies until he found a spot behind a wheel to best view the white-haired man with the voice like a river. He crouched, balanced on the tips of his toes, listening, timing each breath to the man’s.

“Once in a lifetime, ladies and gentlemen. When else will you see a man lift a grown horse using one arm alone? When else, I ask, will you next encounter a girl who can tie herself into a proper sailor’s knot or a seer who will tell you what the Lord himself has destined for you? Never, fine ladies and gentlemen!” With a flurry of movement, the performers hopped back into their carts and wagons, rolled down thick canvas coverings, and pulled shut the doors. Peabody remained, pacing slowly, running a hand over his buttons. “Noon and dusk, ladies and gentlemen. Threepence a look and we’ll happily accept Spanish notes. Noon and dusk!”

The crowd dispersed, returning to carting, washing, marketing, and the ins and outs of Catspawian life. The boy held his position at the cart. Peabody’s sharp blue eyes turned to him.

“Boy,” the voice intoned.

The boy fell backward and a whuff of breath left him. His body refused to heed the command to run.

“That is quite a fine trick you have,” Peabody continued. “The vanishing, the popping in and out. What do you call it? Ephemeral, ephemerae, perhaps? We’ll think of a word or mayhap invent one.”

The boy did not understand the sounds tumbling from the man. Boy felt familiar, but the rest was a jumble of beautiful noise. He wanted to feel the material that wrapped around the man’s stomach.

The man approached. “And what do we have here? You are a boy, yes? Yet you seem to be comprised of muck and sticks. Curious creature.” He made a clucking sound. “What say you?” Pea-body dropped a hand to the boy’s shoulder. It had been months since the boy had encountered a person. Unused to touch, he shuddered under the weight and, doing what fear and instinct commanded, pissed himself.

“Damnation!” Peabody hopped back. “We’ll need to rid you of that habit.”

The boy blinked. A rasping sound escaped his lips.

Peabody’s face softened, a twitch of his cheek betraying a smile. “Do not worry yourself, lad; we’ll get along famously. In fact, I am relying upon it.” He wrapped a hand around the boy’s arm and pulled him to standing. “Come. Let’s show you about.”

Afraid but fascinated, the boy followed.

Peabody led him to the green and gold wagon where a neatly hinged door opened onto a well-appointed room with a desk, piles of books, a brass lantern, and all the makings of a comfortable home for a traveling man. The boy set foot inside.

Peabody looked him over. “You’re dark enough to pass as a Mussulman or Turk. Here, chin up.” He bent down, hooking a finger under the boy’s jaw for a better view of him. The boy flinched. “No, you’re too wild for that.” Peabody sat heavily on a small three-legged chair. The boy wondered that it didn’t break under the man’s weight.

He watched the man think. The man’s fingers were clean, nails trimmed. Different from the boy’s. Though his size was frightening, there was gentleness to him, the crinkles around his eyes. The boy scurried close to the desk where the man sat, listening to his rumbling.

“We haven’t done India before. India,” Peabody said to himself. “Yes, an Indian savage, I think.” He chuckled. “My new Wild Boy.” He reached down as if to pat the boy’s head, but paused. “Would you like to be a savage?” The boy did not respond. Peabody’s brows lifted. “Can’t you speak?”

The boy pressed his back to the wall. His skin felt itchy and tight. He stared at the intricate ties on the man’s shoes and stretched his toes against the floor.

“No matter, lad. Yours will not be a speaking role.” The corner of his mouth twisted. “More a disappearing act.”

The boy reached to touch the man’s shoes.

“Like those, do you?”

The boy pulled away.

Peabody frowned, an expression discernible by the turn of his moustache. His sharp eyes softened and he spoke quietly. “You’ve not been treated well. We’ll fix that, boy. You’ll stay the night, see if it settles you.”

The boy was given a blanket from a trunk. It was scratchy, but he enjoyed rubbing it across his temple. He huddled against the man’s desk, pulling the blanket around him. Once during the night the man left and the boy feared he’d been abandoned, but a short time later the man returned with bread. The boy tore into it. The man said nothing, but began scribbling in a book. Occasionally his hand would drift down to pull the blanket back over the boy’s shoulder.

As sleep overtook him, the boy decided he would follow this man anywhere.

In the morning Peabody walked the boy through the circled wagons, keeping several paces ahead, and then waiting for him to follow. When they came to an imposing cage affixed to a dray wagon, Peabody stopped.

“I’ve thought on it. This will be yours; you’re to be our Wild Boy.”

The boy examined the cage, unaware of the other eyes that looked from their wagons, watching him. The floor was scattered with straw and wood shavings that kept it warm in the evenings—a good consideration, as the boy would be barefooted and naked. On the outside of the cage hung lavish velvet curtains that Peabody had liberated from his mother’s drawing room. The curtains were weighted by chains—to close out the light, Peabody said—and rigged with pulleys. Peabody demonstrated how to surprise an audience by snapping them open the moment a Wild Boy defecated or committed an equally abhorrent act.

“It was the previous Wild Boy’s, but we’ll make it yours.”

The boy took to the act. He enjoyed the cool metal against his skin, and the act allowed him to observe as much as he was observed. Faces gawked at him, and he stared back without fear. He tried to understand the rolls women wore their hair in, why their hips appeared larger than men’s, and the strange ways that men groomed the hair on their faces. He jumped, crawled, scrambled, ate, and voided where and how he pleased. If he did not like a man, he could sneer and spit without repercussion, and would be rewarded for the privilege. He experienced the beginnings of ease.

Without the boy’s knowledge, Peabody studied and tailored the act, learning the intricacies of the boy’s disappearing, perhaps better than the boy himself understood. If he left the child in the cage for the length of a morning, the boy would crouch low to the floor, his breaths would become shallow until his chest barely moved, and then, quite suddenly, he would vanish. Peabody learned to slowly raise the curtain on the disappeared boy.

“Hush, fine people,” he instructed, sotto voce. “No good can come from frightening a savage beast.”

Lifting the curtain was enough to rouse the boy from dissipation. As spectators drew in close to what they presumed was an empty cage, the boy revealed himself. The abrupt appearance of a savage where there had been none made children shout; beyond that, the boy needed do little more than remain mute and naked to drive a crowd to frenzy. The boy found his new life pleasing. He discovered that if he made his penis bobble or flaunted his testicles, a prim woman or two might swoon, after which Peabody would draw the curtain and declare the act successful. He began searching for ways to frighten, hissing and snarling, letting spittle drip from his mouth. When Peabody patted his shoulder and pronounced, “Well done,” the boy felt fullness in his stomach that was better than food.

Though the Wild Boy cage was his, the boy did not sleep in it. Beneath the sawdust and hay lay a hidden door; after the curtains were drawn he undid the latch and climbed into the dray’s box bottom, where a wool blanket was stored for him; from there he made his way to Peabody’s wagon, where a change of clothing was kept for the prized Wild Boy. Peabody would sit at the far end of the wagon chewing at his pipe while writing and sketching by lantern light, occasionally pausing to give a conspiratorial look.

“Excellent take, my boy,” he’d say. “You’ve got a certain flair. Mayhap the best Wild Boy I’ve had. Did you see the missus faint?

Her skirts went over her head.” His belly shook as he clapped the boy on the back. The boy understood that the man liked him. He’d begun to recall words from a time before the woods, words like boy, and horse, bread, and water, and that laughter was good. The more he listened to Peabody talk, the more language began to knit.

Peabody spoke differently to the boy, with a quieter voice than he used with others. The boy did not know that within short weeks of their acquaintance, Hermelius Peabody had begun to think of him as a son.

It began when Peabody did not want the boy to spend an unseasonably cool night in the Wild Boy cage. Perhaps the boy’s thinness inspired pity, but Peabody decided offering the boy a warm place to sleep was a good business investment and would reflect well on his soul. The boy curled up on a straw-stuffed cushion, the same cushion on which Peabody’s son, Zachary, had once slept. Something inside Peabody shifted. Zachary had set out years before to make his fortune, leaving Peabody proud but at a loss. He looked at the sleeping boy and realized his latest acquisition might fill that space. When the boy woke he was greeted by a pile of clothing that was to belong to him. The knee britches and long shirts were no simple castoffs; they had been Zachary’s.

In the evenings, the boy sat on the floor of Peabody’s wagon, listening, picking out names, places, acts. Nat, Melina, Susanna, Benno, Meixel. Peabody schooled him little in social niceties, as he deemed them useless, instructing instead in showmanship and confidence born of understanding an audience. At first the boy did not want to know about the people who looked at him through his bars; he was pleased that the cage kept them at a distance, but curiosity sprouted as Peabody made him watch other acts, the tumbler, the bending girl, and the strongman.

“Watch,” he said. “Benno looks at the lady just so, draws her in, and now he’ll pretend he’s about to fall.” The tumbler, balanced on a single hand, wobbled dangerously and a woman gasped. “He’s in no more peril than you or I. He’s done the same trick with that very wobble since I picked him up in Boston. We lure them in, boy, lure them and scare them a little. They like to be frightened. It’s what they pay for.” The boy began to understand that those who watched were others. The boy, Peabody, the performers were we.

Over a series of weeks, Peabody taught his Wild Boy the art of reading people. Prior to each evening’s show he sat with the boy in the Wild Boy cage. Together they peeked through the heavy drapes and observed the crowd.

“That one there,” Peabody whispered. “She clutches the hand of the man beside her—that one’s half affright already. A single pounce in her direction and she’ll have a fit.” He chuckled, round cheeks spilling over white beard. “And the big man—puffed-looking fellow?” The boy’s eyes darted to a man huge as an ox. “See if he won’t try his hand against our strongman.” He murmured something about using the second set of weights for the show.

The boy began to think of people as animals, each with their own temperament. Peabody was a bear, burly, protective, and predisposed to bellowing. Nat, the strongman, broad browed and quiet natured, was a cart horse. Benno, whom the boy had started to take meals with, possessed a goat’s playfulness. The corded scar that pulled Benno’s mouth downward when he spoke fascinated the boy. The fortune-teller was something stranger. Madame Ryzhkova was both birdlike and predatory. Despite great age, her movements were twitching and brisk. She looked at people as though they were prey, her eyes bearing the mark of hunger. Her voice stood the hair at his neck on end.

They were setting up camp after leaving a town called Rawlson when Peabody took the boy aside.

“You’ve done well by me.” He tapped his hand lightly on the boy’s back and pulled him away from sweeping the cage. “It’s time I do well by you. We cannot continue calling you boy forever.”

Peabody led him between the circled wagons to where a fire burned and members of the troupe took turns roasting rabbit and fish. Darkish men some might have called gypsies played dice; Susanna, the contortion girl, stretched and cracked her bones against a poplar tree, while Nat sat cross-legged, holding the miniature horse securely in his lap, stroking its stiff hair with a dark hand. Weeks prior the boy would have been frightened by them, but now as Peabody tugged him toward the gathering, he felt only curiosity.

Peabody took the boy under the shoulder and hoisted him high into the air, then set him firmly atop a tree stump near the fire.

“Friends and fellow miscreants.” His silvery show voice stopped all movement. “We have tonight an arduous, yet joyful duty. A wonder has traveled among us in this Wild Boy.” The troupe closed in around the fire. Wagons opened. Melina, the juggler with striking eyes, stepped down from her wagon. Meixel, the small blondish man who served as a trick rider, emerged from the woods covered in straw and spit from tending the llama. Ryzhkova’s door creaked open. “This lad has earned his weight and is well on to making us wealthier. It is our duty to name him so that one day, my most esteemed friends, he will be master of all he surveys.” The fire burst and threw sparks like stars into the night. “A strong name,” Pea-body said.

“Benjamin,” called a voice.

“A true name.”

“Peter.”

“A name that carries importance,” said Peabody. Inescapable, the voice buzzed inside the boy, tickling parts of his skull. He stared into the fire and felt his heartbeat rise.

“He is called Amos.” Madame Ryzhkova spoke softly, but her words sliced. “Amos is a bearer of burdens, as will be this boy. Amos is a name that holds the world with strength and sorrows.”

“Amos,” said Peabody.

Amos, the boy thought. The seer’s eyes glinted at him, two black beads. Amos. The sound was long and short, round and flat. It was his.

Meixel found his fiddle and played a bouncy melody that started Susanna dancing and brought about drinking and laughter. Amos watched and listened for a time, but slinked away once he could tell he’d been forgotten. He spent his naming night stretched across the mattress in Peabody’s wagon. Silently he repeated this moniker, hearing each syllable as it had sounded on Madame Ryzhkova’s lips. Amos, he thought. I am Amos.

Late in the night Peabody returned to the wagon and sat down to sketch in his book. It was long hours before he extinguished his light. As he did so, he spared a glance over his shoulder to where the boy lay. “Good night, my boy. Dream well, Amos.”

Amos smiled into the darkness.

Chapter 3

June 22nd

It’s an absurd hour for a phone call, but the more absurd the hour, the more likely someone is to be home. Though the sun is barely up over the water, Martin Churchwarry sounds as though he’s been awake for hours. “Mr. Churchwarry? I’m so glad to reach you. This is Simon Watson. You sent me a book.”

“Oh, Mr. Watson,” he says. “I’m delighted to hear it arrived in one piece.” He sounds excited, almost breathy. “It’s rather fantastic, isn’t it? I’m only sorry that I wasn’t able to hang on to it myself, but Marie would have killed me if I’d brought home another stray.”

“Absolutely,” I say reflexively. After a brief pause, “I don’t think I follow.”

“It’s the bookseller’s occupational hazard. The longer you’re in business, the more the line between shop and home blurs. Oh, let’s be honest. There isn’t a line at all anymore, and Marie—my wife—won’t tolerate me taking up any more space with books I can’t sell but like the look of.”

“I see.”

“But you haven’t called about my wife. I assume you have questions.”

“Yes. Specifically where did you get it and why send it to me?”

“Of course, of course. I mentioned that I specialize in antiquarian books, yes? I’m a bit of a book hound, actually. I hunt down specific volumes for clients. Yours was part of a lot in a series of estate auctions. I wasn’t there about it specifically, I was there for a lovely edition of Moby-Dick; a client of mine is a bit obsessed with it.” There is a jovial bounce to his voice and I find myself picturing an elfin man. “There was a 1930 Lakeside Press edition in the lot I couldn’t pass up. I was lucky enough to have the winning bid, but wound up with some twenty-odd other volumes in the process, nothing spectacular, but saleable things—Dickens, some Woolf— and then there was your book.”

My book. I haven’t thought of it that way, though its leather feels comfortable in my hands, right. “Whose estate?”

“A management company was in charge of the event. I tried to follow up with them about the book, but they weren’t terribly forthcoming. If something has no provenance, their interest is generally low, and the lot it was part of was a mixed bag, more volume than quality. It belonged to a John Vermillion.”

The name is unfamiliar. I know little of my family. Dad was the only child of older parents who died before I was born, and Mom didn’t live long enough to tell me much of anything. “Why send it to me and not his family?”

“The name, Verona Bonn. Wonderful sounding. Half the charm in old books is the marks of living they acquire; the way the name was written seemed to imply ownership. It was too lovely to destroy or let rot any further, yet I couldn’t keep it. So I did a bit of research on the name. A circus high diver—how extraordinary. I discovered a death notice, which led me to your mother, and in turn to you.”

“I doubt it was my grandmother’s,” I say. “From what I know she lived out of a suitcase.”

“Well, another family member’s perhaps? Or maybe a fan of your grandmother’s—people do love a good story.”