Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Books on Demand

- Sprache: Englisch

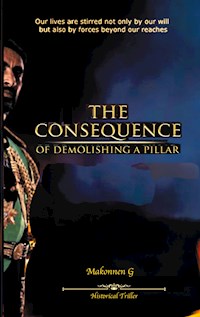

Emperor Haile Selassie was revered as the Messiah by so many people around the world. For almost half a century, he ruled his country quite peacefully until he was smothered to death in 1975. Shortly after his death, strange things began to happen in Ethiopia: civil unrest, mass detention and executions, and war. It appeared as if a powerful spirit was out for vengeance. The CONSEQUENCE is a story of a family in a constant battle to survive the mayhem of the post-Haile Selassie era. ... An Eritrean guerilla fighter in a perilous rescue mission to save his brother from execution... the bloody war in Eritrea.... the barbarous Red Terror in Ethiopia... the harsh torture and extrajudicial killing in the prisons... revolution and counter-revolution, high-level conspiracy and elaborate deceptions, coup de ta and dictatorship, ... amidst all this turmoil, young Daniel has fallen in love and desires nothing but to live and love in peace.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 494

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

In memory of His Imperial Majesty Haile Selassie

(1892-1975)

Haile Selassie was Emperor of Ethiopia from 1930 to 1974. He is remembered as a defining figure in modern Ethiopian history; his contribution to Ethiopia's development, particularly in education and foreign relations, was immense. Ethiopia was a charter member of the UN and the founder of the African Union under his administration.

In 1973, famine claimed the lives of tens of thousands in the province of Wollo, and the emperor was blamed for not tackling the catastrophe as required of him. Taking advantage of this development his opponents instigated mass movement that led to the conspiracy by the army to stage a coup against him. In 1974, a group of young officers deposed him, and installed themselves as a Provisional Military Administrative Council, AKA Dergue. Shortly after the assumption of state power, the Dergue executed sixty of the emperor’s officials without due process of law. The emperor’s grandson, Eskinder Desta and Prime Minster Akililu Habtewolde were among the executed officials. On August 27, 1975 the Dergue smothered the emperor to death while he was under custody. The emperor was 83 years old.

Note:

The naming tradition used in Ethiopia does not have family names. A person’s name consists of an individual personal name and a separate father’s name. In this tradition, children are given a name at birth, by which they will be known.

Dergue: The military junta (108 junior officers) that deposed Emperor Haile Selassie and ruled Ethiopia from 1974 to 1987 is widely known as Dergue. A Geez word meaning "committee" or "council."

Zemecha: A national service program (18 months long) that drafts high school students who are supposed to raise the awareness of the rural population.

Zemach: A student (Age. 18 – 25) drafted in the Zemecha program.

Red Terror: A violent political repression campaign of the military Dergue against its opponents. The red terror was based on the Red Terror of the Russian Civil War and most visibly took place after Mengistu Hailemariam became chairman of the Dergue on 3 February 1977.

Table of Contents

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Epilogue

Endnote

Chapter1

The day had come.

A sleepless night had befallen him; he had fallen asleep only briefly. During that brief time, he had dreamed. As he slid out of his bed now, the dream still floated vividly behind his eyes. A frightening dream, so lovely at the beginning but absurd at the end; the girl he loved just vanished in the air while he held her in his arms.

It had been almost a year since Daniel, 19, had that strange feeling of being drawn to the girl, but he had not told her about his feelings. He was waiting for the right time; a time so perfect that when he told her, she would not laugh but capitulate.

The right time seemed to have come now. Daniel and the girl were supposed to travel to the countryside on a national mission. Last September, while Ethiopia celebrated its new year, a hundred and eight young officers claiming to represent the armed forces had staged a coup and ousted the emperor. The officers announced that they had established a Provisional Military Administrative Council to rule the country, and pledged to reform land ownership in the rural regions, apply good governance in the cities, and maintain law and order all over the country. The Council, widely known as Dergue, declared Socialism as its guiding ideology.

To implement its new ideology, the Dergue summoned the youth to join a development campaign known as Zemecha, a kind of a national service program that would send tens of thousands of high-school and university students out into the rural regions. Many of the students had no idea what Socialism was all about, but they were expected to explain its benefits to the people in the rural regions.

Daniel was one of the Zemachs, and among the first batch leaving today. Unlike the dream, his hope of getting a decent job and marrying his love had never been closer to coming true. The girl was also travelling today to the same region where he was assigned.

Mindful not to wake his brother, Kibrom, who was sleeping on the other side of the bed, Daniel heaved himself to his feet and walked to the window. Carefully, he opened it and let the morning air into the house.

“Daniel,” a voice called from behind him.

“Yes.”

“Is it today?” Kibrom asked, half-awake, his face buried in the pillow.

“Yes, it’s today,” replied Daniel. “Now, will you get up? It’s half-past six.”

Kibrom ignored his request and went back to sleep instead. Daniel walked to the toilet with a towel wrapped on his waist. He bathed his face and the upper part of his body at the backyard's running water pipe. Then he walked casually back, drying his body, and enjoying the cool fresh air. It was then that his eyes caught a sheet of paper stuck between the woods that made the fence. He reached and pulled out the paper that appeared to have been placed there intentionally. On his way back to the house, he skimmed through the lines.

In the bedroom, Kibrom was still sleeping. Concerned not to disturb him, Daniel sat carefully on the edge of the bed and continued reading the paper. The leaflet criticized the Zemecha for its poor preparations and inadequate planning and called on the youth to boycott it.

A boycott was the last thing Daniel wanted to hear. It sounded like aborting a three-month pregnancy. Besides, his conviction in the virtue of the Zemecha was too deep for anyone to persuade him to quit. He had eagerly waited for this day since its announcement three months ago. Decisively, he tossed the leaflet aside, moved forward, and opened the closet. He took out his Zemecha uniform, his shirt and cape, and put them on.

His mother, Abinet, was about to burst into tears when she saw him in the Zemecha gear for the first time. Daniel noticed her attempting to compose herself and control her voice. Yet, her voice quivered as she said, "May God be with you wherever you go, my son," her eyes blinking to deter the tears.

“It’s all right, Mother,” said Daniel. “I'm not alone. There are sixty thousand students; boys and girls, some younger than me.”

Kibrom came yawning and stretching. In his hand was the leaflet.

“Oh, yeah! Our little soldier,” Kibrom laughed, staring at Daniel. “So, you have decided.”

“Well, there is nothing to wait for?”

“Did you read this paper?” asked Kibrom.

“I don’t understand the politics.”

Daniel was more into music and sports than following the current affairs of the country. He had been a soccer player for his school until he got injured last year, and was forced to quit. He exercised in the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA) and often trained in the 5000 metres race.

“How could you trust this government? It’s deceiving the students with promises it won’t keep.”

“I am a student with no knowledge to decipher the mysteries of politics and government.”

“There is no mystery here. Soldiers should not be in the government in the first place. You know that, don’t you?”

Daniel gave it a thought. “I know, Kibrom. But the Zemecha is an obligation we need to carry out. This has more to do with educating the people in rural areas rather than supporting the government. You know that in some places in this country babies are killed for teething on the wrong jaw. Girls are stoned for not found virgins during their wedding day. I think we can make a difference in those places.

As they exchanged these words, their mother, Abinet, was sitting bent over on a stool, fanning the iron brazier on which a teapot was boiling, listening quietly. She did not clearly understand what the Zemecha was all about, but she had not failed to grasp the subject's general idea. She knew that it was peaceful, and no harm would befall the Zemachs. What Daniel mentioned about women’s treatment in the countryside was a matter of personal experience for her.

Abinet’s husband had first picked Abinet’s older sister for a wife. As his first choice was not found intact on the night of the wedding, the bride had to suffer the cruel punishment delivered for such misbehaviour: to be raped by the groom and his best man, flogged, and then hauled back to the family. She still remembered how the groom, now her ex-husband, and his best man came to reclaim their loss.

Abinet’s father, a respected priest, had to hush up the shame that had befallen the family by offering them another wife— a little girl. At the age of 14, Abinet was made liable to save the family from disgrace. Her elder sister, the 16-year-old bride, had to flee from home.

However, there was something ugly Abinet sensed in that Zemecha and did not yet understand. Just months before, the Dergue had executed sixty-three officials of the former regime and a few of its own, including the head of state, General Aman Andom. The shock of that fateful day of November 23, when the Dergue announced the execution as a political decision, still rang in her ears.

"How is the region?" she asked, "and the people?"

"It’s such a rich place and a fertile one. As for the people, you know country-people; they are all the same, harmless and friendly but suspicious," Daniel said as he strode to his bedroom.

He had packed everything he needed for the Zemecha almost a week before. Now, Daniel just needed to do some last-minute packing. He went to the closet and pulled open a drawer from which he fished out the family album. He selected some pictures of his family members and placed them in his wallet.

Sensing someone approaching him, Daniel turned and saw his mother in her Sunday dress. She appeared to have lost considerable weight. The moments of misfortune she endured at various times had left their marks on her face. There were dark rings of worry and fatigue around her eyes. Unable to utter a word that could express his feeling, he bent over and kissed her on the cheek. He, then, turned to the pictures, and put them in his wallet. Reluctantly, he also stuffed in his father’s photo.

From outside, the sound of a car engine cracked. Daniel took his baggage. Abinet wrapped herself up in her Netela, a thin cotton Ethiopian traditional cloth. Even Kibrom put the leaflet aside and stood. They all went out of the house, loaded the baggage on the car, and headed north to pick Ghenet.

Ghenet’s residence was not easily accessible by car. One had to drive a long way around and then walk along the footpath and into the slums. Daniel got out of the car and walked the narrow alley leading to Ghenet’s residence. He jumped over a decayed wire fence for a shortcut to enter the middle of the slum where shyly barking dogs received him. The filthy alleyway was full of washing and garbage. Greeting familiar faces, he met along his way; he reached the old little shack where Ghenet lived with her mother and her siblings in a two-room dwelling.

The door was left ajar.

"Good morning," Daniel called in a loud voice, attempting to be heard over the laughter.

"How are you, Daniel? Come in please," the soft voice of a girl reached his ears. No doubt, it was Ghenet’s voice. As she emerged through the door, Daniel felt his heart jump. His mouth dried up, and he muttered something inaudible.

Though he knew her since childhood, his approach was more reserved, and tense recently. As a result, he was nervous and never seemed to know what to say.

“Are you ready?” he forced himself to speak.

“Yes, mother is dressing up. Come in,” Ghenet said smiling, then stepped aside to let him in. As she smiled, a dimple appeared on her cheek, adding to her beauty.

In Daniel’s nervously watching eyes, Ghenet appeared to be more beautiful today than ever before. His memories must have changed his perception, and his fantasies adding to her beauty because Ghenet had not changed much. She was the same dark brown girl with slightly flat nose set between round cheeks, except that her kinky hair was longer in the front and cropped from behind.

When Daniel entered, the two little children, Ghenet’s brother and sister stopped wrestling and looked at him. From their faces, Daniel could realize that the cruel hands of poverty had seized the throat of this household. The children were skinny and underfed. He approached the boy and the little girl, and kissed their bony cheeks.

“Did you come with your father? I won’t go with you if he is around,” the mother said flatly. She hated Daniel’s father, Goytom Gobezay, for what he had done to Abinet, Daniel’s mother.

“No, not him, but Mother is with us,” Daniel replied.

Never had such a vast number of people gathered in the city of Addis Ababa at one time and place for the same purpose. Over a hundred thousand people had come out to see the Zemachs off. Janmeda, the largest public arena in the country, was crowded to capacity. Those who could afford it had come by their private cars; others by taxis, busses, and trucks. People from the surrounding countryside had walked to the city to celebrate the occasion. The young, the elderly, the rich, the poor of every tribe, and every religion had come. It was an event so unique that it moved everyone and touched every heart.

Even nature seemed to be pleased by the occasion. It was a bright, cheerful day. The thin, whitish cloud that hovered over the eastern horizon was diffusing toward the centre; the sun beyond seemed to be steadily following to take note of the special event.

“That son of yours, over there,” Elsa pointed at the Zemachs who paraded through the stadium saluting the public, “Is he leaving today?”

“Who? Which son are you talking about?” Goytom Gobezay glanced at the beautiful young woman he married after Daniel’s mother.

“Daniel is among the first Zemachs who leave today. Ah! You don’t know. You came just to see your busses.”

Goytom knew that students were conscripted for the Zemecha, but he had no idea that any of his sons would travel today. He was startled when he heard the news from Elsa. He turned to the parading Zemachs and searched for his son, but he couldn’t spot him. Daniel was swallowed by the Zemach crowd who were now receiving the tributes of the cheering mass.

Flowers and green leaves poured down as the young Zemachs in full uniform paraded through the crowd. Flanked by the guard of honour in camouflage suits and the army band, the Zemachs were met by tremendous applause of a delighted citizenry.

As the procession came alongside the tribune, where the Head of State stood, the musicians changed the tune to one of the new songs that had caught the nation's pulse. Instantly the applause erupted again with new force, and every living thing in the area sang the song—Tenessa Terramed - a song that held tragedy from the past and hope for the future.

A moment later, when the applause subsided, a peculiar thing began taking place. Some five or six metres away from where Goytom Gobezay stood, a few youngsters began applauding and shouting a name, “Mengistu! Mengistu!” They agitated the people around to join them. As similar cheers came from different directions, the ovation spread, and, in a moment, the entire Zemach students picked it up. The people, too, applauded in rhythm. It was like a beat of a giant drum, and every blow was accompanied by the loud chant of just one word, “Mengistu! Mengistu!” It was for Major Mengistu, a prominent member of the Dergue, that they were calling.

In the early days of the revolution, though the Dergue worked outside of the public eye, deliberately wrapping itself in secrecy, Major Mengistu was said to have played a significant role in guiding the revolution as the students wanted it. He was rumoured to have been one of the Dergue members who pushed for more radical changes. He was considered the champion of change, and the youth worshipped him.

Goytom Gobezay looked toward the platform and spotted Mengistu flanked by high-ranking government officials. General Teferi, the Head of the state, stood right next to him. When people talked about a certain Mengistu in the new government, it had never occurred to Goytom that this was the Mengistu they meant. He had known this Mengistu a long, long time ago. He had never imagined that the Mengistu he knew could rise to such a height of prominence.

Puzzled and shocked, he continued to look intently at him, scrutinizing his object of concern. The man was Mengistu himself, the same person he knew; flat nose, tiny black eyes, and large lips. His small frame seemed to have grown a little bigger. Mengistu was waving his hand at the parading Zemachs, beaming down at their joyful, happy faces turned on him. He laughed and was tempted to jump up and follow them. Goytom watched him thoughtfully and uttered some expletives before shifting his eyes to the crowd.

“Zemachs! Zemachs!” the loud speakers roared.

Suddenly it was silence.

“Attention! Zemachs are requested to queue up at their respective busses,” the speakers exploded again.

Two of the buses decorated with the Ethiopian flags, garlanded, flowers, and green leaves, belonged to Goytom. As the Nyala Transportation Company's sole owner, Goytom had made a good deal with the Zemecha Headquarters by assigning busses to transport his share of the sixty thousand Zemachs to various regions. He expected to earn quite a lot of money on this deal. He had a similar deal in mind for the return trip some eighteen months later.

He watched the busses move slowly in single file, cleaving the crowds into two. As the busses rolled, he saw mothers weeping, fathers fighting back tears. But soon, they gathered strength, dried their eyes, cleared their throats, and turned their sobs into applause.

Songs and chants, religious melodies glorified the entire scene. To the people, the Zemecha was the one hope left to alleviate their miseries. They seemed to believe that this Zemecha would not remain just as a hollow promise of some politicians but a practical effort that would bring betterment in their lives. This was simply because it was their children in charge this time; they knew they wouldn’t fail them.

Many followed the busses, running behind them as far as their breath could last. In less than a quarter of an hour, the busses were out of sight, out of the city. Then suddenly, it seemed, as though the warmth of the city just went out.

Chapter2

While people celebrated the Zemecha in Addis Ababa, a thousand kilometres north, somewhere in Eritrea, an unfortunate village was burning under a hail of bombs. A few hundred Eritrean farmers lived in the area that was considered as a strategic location for the Ethiopian army to control the western farmland of Eritrea. Thus, the army had built a fuel depot and distribution centre of military hardware in the middle of the village and deployed a special regiment to see its safety.

For many years, the region had been the scene of a civil war of devastating proportions. At issue were questions of self-determination and human rights that had grown increasingly complex as the war progressed. Like many Ethiopians, the Eritreans had hoped the revolution would introduce a new era of peace and reconciliation. But that was not to be; the Dergue approached the Eritrean problem no differently from its predecessor. As military men, Dergue members were ruled by stubborn pride that would not allow them to negotiate with the liberation fronts while the fronts had the upper hand over their troops in the field.

In the first week of May, before the rains came, consolidated Eritrean guerrilla forces suddenly moved to surround the village. They had acquired intelligence reports indicating that there was modern weaponry in the camp. Much out of negligence than contempt, the army had not made any effort to survey the surrounding. As a result, they were not aware of the rebels hovering over them, like vultures waiting for a dying man.

Over the weeks, the rebels intensified their siege, disconnecting the army from any possible supplies and communications except the radio. It appeared the army had no option left other than surrendering if help did not arrive in time. Realizing that its successive call to the head-quarters had come to no avail, the army decided to break out of the suffocating predicament all by itself. As a result, full-scale fighting broke out.

Since the government troops had been cut off supplies for several weeks, they soon ran short of food and water. On the contrary, the rebels were yearning to get hold of the weaponry that would play a decisive role in the struggle to come. So, they fought determinedly to win the battle. At last, the army was to suffer the humiliation of defeat. Before it surrendered, though, it had managed to transmit the final message to the headquarters to whom it revealed the imminent collapse.

Afterwards, while the rebels had been busy collecting the weapons and tallied captives, the sky suddenly turned into a stage of fire theatre. Fast-moving machines invaded the airspace and tore through the air from every direction. They dove, banked, and sored with tremendous speed. Then they began the real job: dropping bombs and explosives, killing indiscriminately anyone who stood on two or four feet, including government troops. The reasoning behind this horror was to destroy the weapons before the guerrillas could lay their hands on them.

The camp erupted in flame and explosives flared up, wrecking the entire cache of weapons. In less than a quarter of an hour, they reduced the poor village into ashes. No one appeared to be spared from the inferno.

On-board the Ethiopian jetliner that flew over the village of Awgaro on that day was Daniel's cousin, Ermias Tesfay, travelling to Addis Ababa. Sitting by the window, he was purposefully surveying the outside with a binocular. Below was the Great Rift Valley, as magnificent as it had always been since the day of creation, stretched from Syria, through the Middle East, and the Red Sea, to Ethiopia. As he thoughtfully observed the grand basin, a sense of belonging crept upon him that soon transformed into a distressing feeling of misfortune. Suddenly, a question crossed his mind. Could the cause of the bloody conflict of this region be the natural wealth that lay beneath this valley? “What sort of wealth is there?” Looking to the east, towards the Middle East's petroleum empires, he wondered if the answer to his questions might be “Oil!”

As the plane entered the heart of the Eritrea air space, Ermias' glance drifted at the passengers. Very few Europeans, a couple of Orientals, a dozen or so Arabs, the rest were, of course, Ethiopians. Tourism had collapsed since the change of regime. Many of the Ethiopians were diplomats on their way home to be briefed about the Revolution. Some were radical scholars summoned by the ruling Dergue to replace the officials of the former regime.

Ermias exchanged friendly glances and smiles with a couple of passengers and then resumed looking out through the window. It was about 2 p.m. the sky was as translucent as the water of the ocean. One could see from one end of the horizon to the other clearly. Ermias watched as the stony mountainous desert of the Sahel came into view.

Then came the barren Barka pasture, frighteningly naked, no grass, and no vegetation. A stranger observing Eritrea from the sky would hardly believe that there was an eighteen-year-old war of liberation going on. One would tend to discard the very notion that there could be any living soul who would wage war to liberate and preserve that barren land. There was nothing to fight for, one would say.

“Hi! How is the journey?”

Ermias turned to see the speaker. A tall, dark-skinned man who looked like a prize-fighter was staggering down the aisle between the seats, greeting everybody with a smile as he passed by.

“It's fine,” Ermias was brief.

The tall man walked past Ermias to the rear end of the aircraft, presumably to the toilet. A few minutes later, the man returned. As he lowered himself to occupy his aisle seat, the aircraft's front tilted upward to gain altitude. As the man staggered off balance and fell on the floor, Ermias saw a pistol on the man belt.

“Anti-hijacker,” Ermias assumed.

Realizing that the aircraft was gaining altitude, Ermias shifted his gaze to the outside. He reached for the binoculars and peered at the country below. He didn't like what he saw on the ground. A small village was burning, thick black smoke spreading over it. His heart suddenly pounded hard. Withdrawing his handkerchief from his pocket, he first wiped his eyes and then the binoculars. Overwhelmed by sudden emotion, he looked down again; it was the village of Awgaro. He had information that it was under siege but had not known that fighting had broken out.

He saw the killing machines darting through the sky like rockets, two F-5 bombers spitting death over the village below them. The Ethiopian Air Force in the line of duty! Ermias' heart erupted with concern as he envisioned the poor villagers, the children caught in fire, women ripped apart, old people reduced to ashes.

As an undercover operator for Eritrean Liberation Front, he had been able to bear witness to numerous atrocities committed by the Ethiopian forces at various times. He had seen villages blown to ashes; innocent people mowed down in marketplaces and other public places. He had seen enough of the Ethiopian rule in which young men were arbitrarily arrested and summarily executed as suspected supporters of the liberation movement. Those images flooded his thoughts, raising his rage and repressing his reason.

A strange and powerful feeling surged through him and urged him to make a move, like to grab the pistol from the anti-hijacker and force the pilot to fly at the bomber's altitude. He pondered if those bombers would stop their deadly operations to avoid a collision with a civilian aircraft. His mind was filled with a frenzy of thoughts.

Ermias was a spymaster, diligent and unafraid, but he was not trained for such an encounter. Nor was he a skilled fighter type to overpower the anti-hijacker. He was tall and gangly, with stooping shoulders, a not muscular but firm body. However, he did not doubt that he could snatch the gun if he could move to the security man undetected.

As his heart pounded faster with anxiety, the plane reached the heart of the village. Just before he made up his mind to storm over the security man, Ermias gazed out again. He couldn't see the village; it was right under him. Instead, he saw a thick smoke of a rapidly descending fireball filling the space below the aircraft. Once again, he could not trust his eyes. It appeared like one of the machines of destruction had been blown up. He almost stood to applaud, forgetting that he was in the enemy’s territory. Thrilled with what he had just witnessed, he observed the other bomber rushing further to the west for safety.

The bombing had ceased.

Ermias' eyes darted toward the anti-hijacker whose seat was now vacant. He looked right and left but could not spot the man. Though thrilled by his compatriots' success blowing a fighter jet, he was still high on adrenaline. But soon, his emotions subsided, and he began thinking of the consequences had it gone his way.

“Terrible,” he thought.

He waved to a hostess and ordered coffee. Ethiopian coffee tasted good; it was probably the best in the world. Ermias liked it. Sipping the coffee, he tried to relax. The plane was now deep into Ethiopia, the country that held many memories for Ermias. He suddenly felt isolated and withdrew into himself, no longer conscious of the other passengers or the lush green country below. Both sad and happy memories unfolded in his mind

Ermias was born into a middle-class family in the city of Asmara where he went to the Italian school that had been established in 1903. His childhood life was noticeably well compared to the other children in the neighbourhood. Despite his mother’s death at an early, he was not deprived of a parent’s love. His warden, a close relative to his father had been able to cover the gap and make him feel comfortable, but the death of Ermias’ father was so sudden that Ermias still had difficulty accepting it after so many years. It had been such a tragic incident that he had felt almost demented when he heard about it.

During the period of the Ethio-Eritrean federation, Ermias' father, Tesfay Kahsay, had been a member of the Eritrean political party. He advocated the idea of maintaining the federal arrangement as some encouraged complete unification, and others promoted total independence. At times, these internal conflicts had led to violent undertakings.

Taking advantage of that situation, the Ethiopian government had begun supporting the Unionist party that favoured unification, as it repressed the federalists and the separatists. Thus, the idea of complete unification begun to pick momentum. With the Eritrean Orthodox community's support, the unionists pushed to pass legislation that facilitated the erosion of Eritrean autonomy. In 1958, they voted to discard the blue-coloured Eritrean flag, replacing it with the tricolour Ethiopian flag. A year later, they replaced the Eritrean Penal Laws with the Ethiopian Penal Code. Then in 1960, it resolved to call the designation "Eritrean Government" as "Eritrean Administration" and the "Chief Executive" as "Chief Administrator."

Now that all preparations had been made, the Ethiopian regime could take the last step to the final goal. On November 15, 1962, Emperor Hailesilassie issued Order No. 27, declaring the termination of Eritrea’s federal statutes. Eritrea “hereby wholly integrated into the unitary system of the Ethiopian Empire.”

That angered some Eritreans and exhausted their patience. Ermias' father was among the first to make up his mind against the Ethiopian government's actions. Even before the formal dissolution of the federation, anti-Ethiopian sentiment had grown in Eritrea. Demonstrations, strikes, and other overt forms of protest had given way to clandestine political movements. By 1961, these movements had already created the setting for the emergence of an armed struggle. Equipped with obsolete Italian rifles, the Eritrean Liberation Army's earliest unit fired the first shot in September 1961, marking the beginning of a long, tragic war.

Ermias' father had been one of the leaders who organized themselves to liberate Eritrea from Ethiopian rule and make it a sovereign state. As there was an aggressive drive to prepare the people for liberation, he had been sent to Addis with the mission to organize Eritreans living in the heartland of Ethiopia. He had worked day and night and succeeded in organizing several people. Eritreans who lived in Ethiopia began to make material, moral, and financial contributions to the cause. Tesfay had been able to assemble hundreds of people in less than six months and collect a significant amount of money.

The Ethiopian government soon realized the danger posed by the liberation movement and devised ways of curbing those disruptive activities. The authorities arrested Eritrean activists, and covert assassinations became a common occurrence. As suspected Eritreans were persecuted both in Asmara and Addis Ababa, many disappeared, some went into exile, and few were found dead. Tesfay spared himself from the atrocities of the state by disguising and hiding until he accomplished his mission. He had almost made it back to Eritrea had he not stayed in Addis one day longer than he should have. He had been found dead in the middle of the city the day he was supposed to leave Addis, with no trace of the money collected to support the Eritrean movement.

The news of the death of his father had been a shocking blow to Ermias. It was so stunning that he could not cry or weep as though the grief had been like a fire that dried up every drop of fluid in him. Since his mother died few weeks after his birth, his love for his father had been twice more than any child could have for a father. With both his parents deceased, he had come to Addis to stay with his aunt, Abinet Kahsay and her husband, Goytom Gobezay. Back in Eritrea, there had been no one to look after of him.

After his father's death, Ermias had transformed from the cheerful child he had been once into a sad, mistrustful, and lonesome boy. He walled himself off from the world, retreating silently into some remote and lonely shadows of his mind. He had begun to look at the humanity around him with a suspicious eye, afraid of the forces of evil that had deprived him of a father. Some malignant fate had snuffed out the warmth and the light in his life. For Ermias, the world had changed forever; it had become full of menace and danger.

It had been under such circumstances that he went to school. Not surprisingly, Ermias' school performance had been inadequate. Neither was his behaviour pleasant. He did not play with his peers as children of his age should do. He spent most of his time thinking about his father's death and the cruelty of the world.

Shortly after Ermias' father died, Goytom Gobezay had bought the three-room house in Kera where Abinet resided now, and the family moved to the new house. Ermias and Goytom’s children, who then had reached school age, joined the Shimelis-Habte-School, the nearest around.

However, Ermias' condition had not improved. Worst of all, he began to skip classes, and he failed his exams. As the years went by, Goytom Gobezay prospered more and more. At the same pace, Ermias grew and developed a striking resemblance to his father, which seemed to trouble Goytom. If Goytom had been having fun playing with his children, he would stop as soon as Ermias joined them. When Ermias would talk directly to him, Goytom would just pretend as if he had not heard. When Ermias would repeat what he said, he would yell at him. Most of the time, Goytom shouted at him for no reason. Using Ermias' failures as a pretext, Goytom had made it a habit to abuse the boy, often insulted him and beat him. When things got tense, Goytom’s rage often spread to the rest of the family. His mistreatment would befall almost everyone except Daniel and Biniam, who were not at school age at the time. Abinet had been the one who had to suffer the most as she tended to protect her nephew from her husband's wrath. The agony his aunt had to experience because of him had been a distressing pain Ermias had to cope with.

At the age of seventeen, Ermias showed some changes. He began examining the documents he inherited from his father: letters, articles, memorandums. He also began to touch on Eritrean history in his quest for knowledge of the past. Deeply impressed, he studied history from the ancient Axumite era up to the Italian colonization of ERITREA. He learned why the British ruled for ten years in Eritrea and the subsequent Ethio-Eritrea federal arrangement. He also examined the process that led to the Ethio-Eritrean unity, which helped him develop a pointed interest in the liberation struggle. He began to look at his father's death in light of the independence struggle in Eritrea. From the history of Eritrea, he realized that his father's death had not been in vain.

After his father’s death, the liberation struggle had grown by leaps, and that proved to Ermias the righteousness of the cause. It was at that time in his life that he started to see the light again. The grief and pain he suffered in his boyhood began to give way to hope and a vision of the future. As he entertained the thought of joining the liberation struggle under the banner for which his father sacrificed his life, he had been able to soften the pain of loss and respond to the pleasure of life.

Subsequently, his appetite for education grew tremendously. He began to register impressive results in his studies. He made friends in and outside of school. He met a girl named Saba Berhe and fell in love with her. Apart from the recurring quarrels with Goytom Gobezay at home, every other aspect of his life had taken a new turn.

As Goytom had used Ermias' learning problems as a pretext to beat him, his improvements had also begun to make Goytom uneasy and wary. Upset with his business, Goytom came home one day, and wanted to unload his frustration on Ermias. To his surprise, Goytom was stopped by the adult boy who planted himself squarely in front of him and, looking into his eyes, told him: “I'm grateful that you raised me like one of your children, but at times you have been beating me unfairly. I can't take it anymore. I'll leave this house soon. Until the day I leave, please be patient!”

From that day onwards, Goytom did not dare touch him; and Ermias didn't stay long. A new era had come when Ermias and Goytom could not live under the same roof as Eritrea and Ethiopia could no longer remain under the same crown. In the summer of 1970, at the age of 20, Ermias left to join the independence struggle.

As the plane came closer to landing, Ermias remembered his first love, Saba Berhe. Departing from Saba, whom he had shared with wonderful and innocent times, had been a painful ordeal he had to sustain. After six years, Saba still had her place in his heart. The memory of the joy he shared with her for a relatively short period was still vivid after those long years of separation.

“Where would she be now?” he thought.

At precisely 3 o'clock, the plane touched the ground at Bole Airport. A moment later, he was out of the airport, speaking with the man assigned to meet him.

“Any problem?” asked the host, a tall and diligent-looking young man of 25 named Jovani, born to an Italian father and Eritrean mother. He owned an Italian restaurant which he inherited from his father, a 5-room villa and a fiat 124 spider. Jovani was one of the few Eritreans who led quite a lavish lifestyle.

“Nothing,” Ermias said, voice dripping with melancholy that caused his shoulders to droop low.

The two had met a few times before in Sudan, but their acquaintance remained remote due to their encounters' brevity. Except for the greeting they exchanged, they did not say much to each other until they were well in the middle of the city. Jovani was just as eager to hear news from the battlefront as Ermias wanted to find out about the changes in Ethiopia. He looked right and left to see if the marks of the Revolution could be detected on the dwarf buildings, the narrow boulevards, and the hidden villas. When he found nothing from the dull street, he turned to Jovani.

“It looks very calm, doesn't it?”

“But underneath, it's boiling,” said Jovani.

“What we hear outside the country is exciting.”

“This revolution is not ours. There is nothing for us in it,” replied Jovani and began telling his story. He related the recent horror in which twenty-four Eritrean businessmen and workers had been secretly taken to Awash and summarily executed for allegedly being members of the Eritrean Liberation Front.

“We cannot live with these people,” he said bitterly at last. “We have to continue the struggle. How is it? We heard that our fighters are gaining…” he left his speech suspended in mid-air, trying to incite Ermias into talking. When he did not hear a word from him, he went straight to the heart of the matter. “We heard that our fighters would soon capture Asmara. Isn't it true?”

“Our struggle is long,” said Ermias, his eyes fixed on the outside, not looking at anything but on something much more remote than the life on the street, something abstract and intangible: victory.

Ermias had never had illusions about victory. As times passed, victory seemed to run farther and farther away, getting increasingly unattainable, partly because the Eritrean cause had virtually no support from the international community, mainly because the liberation fronts were uncompromisingly divided among rival factions. He had, unlike Jovani, no illusions of victory. “Our struggle won’t be short,” he said again and lapsed into vagueness

Jovani parked the car along the street side in front of Bar Tiku at Tekle Square, a crowded area full of beggars, prostitutes, unemployed youngsters and brokers.

“This car will be at your disposal as long as you're here,” Jovani said and bent to pull something from a pocket under his seat, “And I have got a small gift for you.” It was a 0.22 pistol in a shoulder harness of brown leather. He reminded Ermias to avoid wearing it but keep it in the car safe by day and sleep with it under his pillow by night.

Ermias searched the young man's face for any sign of mockery, but he found none. Jovani's final words were sober and appealing, “This is an assassin town where people get killed for teasing at a little cadre of the revolution.”

As he climbed out of the car, Ermias observed the coolies walk past with baskets balanced on their skinny shoulders, poor countrymen with their donkeys crossing the street, fully packed shabby busses rolling. The area was filthy. It had a horrible smell, the air dense. Then his eyes fell on the grey Toyota and his thoughts on the little pistol, by which he would end himself if the situations compel him to do so.

Chapter3

Inango was a small dusty village with a single gravel road passing through it. On the eastern side of the road were half a dozen dwarf brick buildings that housed the post office, the telephone office, and other government offices. On the opposite side of the road, several mud houses lined up like ragtag soldiers at attention. Then came a tea-room, a shop, and a barbershop.

Behind the houses, the village's poor inhabitants survived inside crumbling huts. The adults wore no shoes, and the children went half-naked. In that village, the Zemachs, with their uniforms, caps and leather shoes, were regarded as exceptionally privileged creatures.

Daniel sat in the barber's noisy wooden chair staring through the glass window while the barber worked on his hair. It was Friday; he had finished work an hour earlier than on regular days. The Zemecha compound lay a few blocks to the left of the post office.

“It looks peaceful,” the barber said, staring at the compound across the road. A few Zemachs were playing volleyball on the field. The building, with its hangar-like houses, had primarily been planned to serve as a primary school. It consisted of several rooms, a large dining hall, three dormitories for some thirty Zemachs, and two other office rooms.

“Not as it used to be,” Daniel said, referring to the first few weeks since Zemachs came to Inango. The villagers had welcomed them with open arms, eager to learn from the esteemed Zemachs. Now a weary cautiousness lined the faces of the same villagers. Peace hung in the air only because the opposing sides hid their distrust behind plastic smiles and sweet words masking the poison in their hearts.

“In just a few weeks, I have watched them accomplish much,” said the barber as he finished cutting Daniel's hair. “I don't understand why some are complaining now.”

Daniel heaved himself out of the chair. “Real changes take years, and some won't wait that long,” said Daniel as he paid the barber.

Brushing off bits of hair, he stepped up to the long, cracked mirror on the wall, which held the reflection of his entire 172 cm lean frame. He searched his face, which appeared to have grown thinner since he came to Inango. Yet his black, curious eyes remained mature and purposeful. The brown complexion, which had had a boyish smoothness before, now looked bony and rugged. From the change in his face, one could see the hardship the Zemachs were experiencing.

The Zemachs had found living among the farmlands cumbersome and were ill-prepared for the work that accompanied such a lifestyle. The first few weeks were manageable since they were busy establishing farmer’s associations and redistribution of the land. In Inango and its surrounding regions, thirty-five associations had been created, and land had been redistributed according to the new legislation. As that had been completed with insignificant resistance from the former landowners, preparing the land for the next harvest proceeded expeditiously. That had, however, been the most challenging part of their work.

As the rainy season approached, the Zemachs had to participate in the actual digging and tilling part of the fieldwork to contain every drop of rain. Many were injured as they return home in the evenings with bleeding hands or swollen feet from toiling in the land beside the farmworkers.

Everyone worked according to their abilities toward the completion of the job. The farmworkers were as happy as they had ever thought it possible to be. Of course, there were a few lazy Zemachs who rose from bed late each morning and left work early; however, most were diligent and learned quickly. Despite the hardship, Daniel, too, worked from dawn to dusk and was always where the work was hardest.

Performance and perseverance could add eligibility for a government job or admittance to higher education in the future, but Daniel never thought of that; he was only driven by a sheer sense of obligation and the joy of seeing improvements. As a result, he learned to till the land, and he loved the smell of the earth.

The discussion sessions were held on Tuesdays and Fridays, which proved to be both motivating and educational. During these sessions, they discussed society, politics, the environment, human rights, and the changing role of women. Daniel never missed a single session and was unafraid to ask questions or to speak his mind.

He was thinking about this new life as he reached for his cap and put it on his head. When he turned, he saw his face in the mirror and flashed himself a smile, and stepped out of the barbershop. Outside, the sun had already made most of its way across the sky. It would drop behind the mountains in less than an hour, and darkness would fall over the unelectrified village. Their discussion session would proceed after dinner under the glowing light of a few lanterns. Today's discussion, Daniel had learned, would be on People's Right to Self-determination.

Just before he was about to cross to the post office, a truck passed westward on the road, followed by a horse-drawn cart, raising a cloud of dust behind it. Daniel received two letters at the post office. One from his younger brother, Biniam, and the other strangely was from Ghenet. He found that unusual because she had never written before; there had been no need to. She was not that far away. Besides, not a week had passed since he had met her in Gimbie, a small town where Ghenet was posted for her Zemecha duty.

He opened Ghenet's letter first. It was dated Tuesday, June 17, three days before. She wrote that she had planned to visit him on Saturday, the following day. When he folded the letter and stuffed it in his shirt's pocket, he felt his heart beating faster with a pleasant wave streaming through his body. He almost forgot his brother's letter.

As usual, Biniam's letter began with greetings, then continued, 'Mother is worried because of Kibrom's strange behaviour. He comes home very late. No one knows where he spends his days. He doesn't talk to me, nor does he listen to Mother. Mother is worried about him. When you write to him, try to make him understand what Mother is going through and why. I think he will listen to you. I suspect he has joined a certain political organization. I have observed unpleasant things around him, such as firearms. I'm still working in Nyala Transports. Father has decided to sell it. I don't know why? We are all fine except that we miss you…'

With mixed feelings of concern and delight, Daniel walked to the Zemecha centre. He was worried about his brother who could end up in jail like many of the students involved in political activity. As he entered the Zemecha compound, Ghenet came in his thought and filled him with happiness He went on whistling the new national anthem, which had been introduced along with the change of government. Like many of his generation, Daniel enjoyed the tune and cherished the lyrics because it revived a unique feeling of love for one's country.

He entered the room, a kind of ward with a dozen beds in it and a long table and benches down the middle. The chamber still held the oppressive heat of the day. As his eyes adjusted to the darkness, he saw his roommates, Kirubel, changing clothes, and Kebedde, lying on his bed at the corner of the room. Kebedde was a student at Haile Selassie University in Addis Ababa who, since he came to Inango, had been agitating the Zemachs to quit the Zemecha. He was in mid 20s, but looked much older.

“Oh! Here comes another loyalist who refused to quit, ah,” said Kebedde pointing at Daniel,

“If I ever start, I never quit,” said Daniel solidly,

“You are misled.”

“I am not. I believe in the cause. For almost a decade, the slogan was Land-to-the-Tiller, was it not? Now we have it, and when we need to implement it, you run away. How can you run away from what you know is right and just for the people? I don't understand you.”

“Read these leaflets. It's all there if you can understand it.”

“I have read it. I don't share its opinion. I'd rather say that this Zemecha would broaden our horizon.”

“What's here in the countryside that would broaden you? It's in the city where our party is flourishing: in the factories and schools.”

“What party?”

“You don't know? You are living in a different time, Daniel. You must wake up.”

“I know what I need to know.”

“Look, you have got to read this. It's all there,” said Kebedde, pointing at a leaflet.

“I told you that I have read it and did not like the idea of quitting the Zemecha at this stage,” said Daniel, with a clear indication to avoid the subject.

“That's because you don't know what is going on.”

“What's going on? If I may ask?” Daniel shot back.

“A People’s movement to overthrow the fascist government: the Derg,” Kebedde replied.

“I may not know about fascism or Dergue or whatever, but I do know there are many less fortunate people around. I'm here to do something to improve their lives,” Daniel responded.

“You sound righteous when you say that, but soon we shall find out your connection with the government.”

Daniel was startled by the remark and turned to Kirubel, “What is he talking about?”

Kirubel was a high school student, very close to Daniel. He was a humble person who simply liked the company of his friends more than their opinions. If his friends had not joined this Zemecha, Kirubel would not have been here.

“One or two spies have already been discovered among us, Daniel,” Kirubel answered.

“Kebedde, are you implying that I could be spying on my friends?” Daniel asked, surprised.

“Who knows?” Kebedde said menacingly, rising from his bed, and left the room briskly

Kirubel, feeling that he had offended his friend, stepped closer to Daniel. “Look, Daniel…”

Daniel interrupted, “I know you meant no malice towards me, Kirubel, but it surprises me that you, of all the people, should say that to me.”

“Well, I meant to bring the rumour into the open so that you can defend yourself.”

“I don't have to defend anything,” Daniel replied defiantly.

“But you should join the student community, their struggle, and their party.”

“Party? And what does the party say about this Zemecha: quit?”

“It criticizes the Zemecha for its poor preparations and has called on the youth to boycott.”

“That's what I don't understand. There is nothing wrong with this Zemecha. We are helping the poor. Just look at what we have achieved so far. Until now, work had been done considering the existing reality, and isn’t that okay? Central planning has not been crucial,” Daniel said.

Kirubel seemed to lose ground. He was not Kebedde's type, who understood the politics and the teachings of Marxism. Kirubel was an individual who had no opinions of his own, always found holding the person's beliefs to whom he had last spoken.

“I didn't know much about this,” explained Kirubel, “but if you read the EPRP, I am sure you will change your mind. I read it, and it changed me. It's a party struggling for genuine democracy. It calls on the Dergue to lift all restrictions on democratic rights and step down and allow the formation of a people's government.”

“You stop preaching me EPRP,” said Daniel, “now, let's go for a walk.”

“What's going on in this place? Many of these guys are not as friendly as they used to be towards me,” Daniel said as they walked down the gravel road.

“You are so fascinated by the work of the Zemecha that you haven't noticed what's going on around you,” Kirubel pointed, “The division between the political organizations is growing.”

“What does that have to do with me?”

“Kebedde says it's because of your social class; you have not joined the students…the EPRP.”

“What class?” Daniel seemed puzzled.

“Your father owns the Nyala Transportation Company. He is regarded as a wealthy man—a bourgeoisie,” Kirubel said with a shrug of his shoulders.

“If he only knew how I was raised.”

“What do you mean, Daniel?” asked Kirubel, showing concern in his furrowed brow.

“My father may be one of the few fortunate men in this country, but I did not benefit from his fortune. He left the family years ago, and we saw very little of him, and his money,” Daniel's contempt for his father flew from his lips as he spoke.

“I'm sorry. I didn't know that,” said Kirubel.

“Anyway, it's not because of social class that I did not join the group. It's because I don't know anything about it. Whatever I hear about EPRP isn't different from what I hear about its rival, the socialist party,” Daniel replied.

“But the majority is with the EPRP.”

“Yes, but what exactly does the majority know about the EPRP?"

“Well, I don't know. I guess the majority is always right,” Kirubel admitted.

Daniel smiled, “Not always, Kirubel. I think a majority tells the total number of people wishing the same thing, not the number of smart people.”

The following day the Zemachs were ordered to interrupt their half-day work and assemble in the compound. The night before, security people had visited the place and detained a teacher called Bezabih Mazengia, a Zemecha leader, the students held in high esteem. Late in the evening, a session chaired by Mr. Bezabih had been conducted right after dinner. The topic at that time was Eritrea and the Liberation movement, a sensitive issue but interesting.

In the middle of the hot debate, Bezabih had boldly given his opinion that the Eritrean people had the right to self-determination and that their struggle against the Dergue was just. Someone had leaked to the security forces about the topic of discussion and Bezabih’s speech, and they came late in the night to arrest Mr. Bezabih. Some Zemachs blamed his arrest on pro-Dergue students and retaliated by beating them and chasing them out of the compound. The Zemachs had expected that the Station Chief would say or do something about it.

The Station Chief stood on the porch of the so-called office facing the volleyball field where the Zemachs assembled. From there he could sense the division that had torn the Zemachs apart. On the face of every Zemach reflected mixed attitudes, some resentful and vengeful, others terrified and anxious but all calm.

The Station Chief began speaking to the Zemachs, criticizing the fight that had broken out in the dining hall the night before.

“Those anti-people elements among you who are striving to divide you and sabotage the Zemecha…,” the chief's speech was suddenly interrupted.

“Release Bezabih!” someone shouted.

“Who betrayed him?” another one cried.

Daniel and Kirubel stood together, leaning on the volleyball pole. Daniel asked, “Where did they take Bezabih? Why?”

“You heard him yesterday, supporting the Eritrean question.”

“But he has the right to speak his mind.”

“Oh yeah! You gave him that right or what?”

“Without Bezabih, this place will never be the same,” said Daniel; his eyes darted to the Chief, who was trying to make himself heard over the crowd. As the Chief attempted to continue his speech, the Zemachs screamed at him, demanding to know why the police arrested Bezabih. Once again, he relented to a verbal assault by the crowd.

When the outcry died down, he said, “Okay! We will see what we can do about Mr. Bezabih. I hope it's some misunderstanding. But we have to continue our work with or without him.”

That afternoon, there was no work. Daniel and Kirubel sat on the roadside, waiting for Ghenet.

“How long have you known her?” asked Kirubel.

“Since childhood - the same neighbourhood, the same school. Our brothers were good friends; our families are well acquainted. She is a kind of a sister to me.”

“When did you begin to see her differently?” Kirubel asked with a smile.

“I guess it all started quite a while ago, but I gave it more serious thought since the Zemecha began.”

“That's when we all began to mature. You need to tell her about your feelings,” Kirubel suggested.

“I couldn't do that. I tried the last time I was with her, but I couldn't speak out the words,” Daniel said.

“What about her? What do you think she feels toward you?”

“I think she has the same feelings that I have for her, but she expects me to take the first step.”

“Then take it, Daniel. What are you waiting for?”

“The right time,” Daniel shot back.