2,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Noel Gray

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

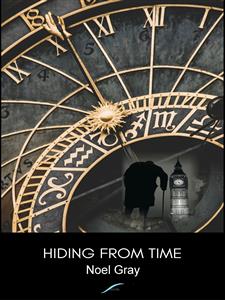

The Dead Gondolier and other crimes of Venice A collection of twelve stories set in Venice and nearby islands. Each tale involves a different crime, and factual information about the city and its history are woven into every plot. The main character, Pio Scampi, is a Carabinieri officer who spends most of his time thinking about food. He is generally assigned the more difficult or strange cases, and his team of detectives do most of the legwork, usually based on circuitous questions he raises about the crime under investigation. The detection techniques employed are more psychological than scientific and the crimes themselves reflect the specific character of the city and its inhabitants.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

Noel Gray

THE DEAD GONDOLIER

© Noel Gray 2016

ONDINA PRESS

www.noelgraybooks.com

Contents:

The Dead Gondolier

The Fouled Referee

The Foolish Friend

The Ill-Fated Mariners

The Disappearing Actor

The Cunning Magician

The Deceived Hero

The Cheating Bureaucrat

The Doomed Colonel

The Sly Engineer

The Missing Skeleton

The Useless Expert

to Laura

The Dead Gondolier

“Maresciallo!” yelled an impatient voice on the intercom, “my office, immediately.”

“Yes, Sir,” said Pio Scampi, rising from his chair and slowly walking down the corridor to the office of Captain Paolo Foscarini, the head of the Venice Carabinieri.

“Take your time, Maresciallo,” snapped Foscarini when Scampi finally arrived. “Here,” he ordered, handing a file to the most experienced man on his force, “take charge of this. And don’t tread on anyone’s toes doing it,” he sniped. His subordinate had a genius for upsetting the wrong people.

Scampi ignored the comment. The Captain was not himself these days. Getting divorced was never easy. Scampi saluted and went back to his office. He slumped in his chair and studied the file’s contents. A gondolier, Amadeo Despotti, had been found at first light the day before, floating face down near the Canale Rio Della Croce in Giudecca, the spine shaped island directly opposite Venice. The body was several meters from a gondola tied to mooring rings at the mouth of the canal. Despotti had drowned. The boat was later identified as belonging to the dead man. Scampi stared at a photograph of the corpse: a healthy, good-looking boy, not unlike countless others of his profession. Too young to be dead, and now too dead to ever become old.

Scampi pressed a button on his intercom. “Rullo, come here for a moment, please.”

“Yes, Sir,” screamed Gino Rullo. Seconds later the subordinate officer dashed into Scampi’s office, eager to discover the reason for the summons.

“Read this preliminary report and tell me what you think?” said Scampi. “And please, don’t shout the barracks down. I’m old but my hearing remains young.”

“Sorry, Sir,” Rullo grinned and quickly read the first few pages of the file. “Hmm, a drowned gondolier. Gondoliers are among the finest boatmen in the world, so they don’t drown, Sir, except in alcohol,” he added with a snigger. Like many young men of Venice he resented the winning ways of the gondoliers with the girls. “And what was a gondolier and his boat doing at Giudecca? Their turf is the main island. I’ve never heard of one working at Giudecca. Never!”

“Good, Rullo. Now, let Cossutta and Gazzera read the file and then send them to interview Despotti’s family. Then, tell De Sica to get his boat ready and let’s visit that canal. Tell Corrio I want him along, too. Remind De Sica to bring plenty of cigarettes.”

Rullo could hardly contain his excitement. Marco De Sica only smoked Camels; Scampi only smoked De Sica’s Camels when a case was strange enough to blow away the fog that usually surrounded his personality. The young officer snapped a quick salute and then ran out, reminding himself that he’d better ring his mother and tell her he wouldn’t be home for lunch. Squid cooked in its own ink; the most famous dish of Venice. He’d never hear the end of it. Thank god he lived on the barracks. And thank god his mother didn’t know Scampi by sight. The fog of Venice meeting the volcano from Naples; a clash of the gods he could live without.

An hour later a shiny, black and white motorboat with red trim and the number 103 on both sides of its bow, crossed the Canale Di San Marco that separated the Eastern tip of Giudecca from the main island. The Venice Carabinieri were very proud of their boats and their nautical skills, as indeed were all those who made their living plying the waters of the famous lagoon. De Sica was no exception. He was therefore mystified as to how a gondolier could drown. He had read the autopsy report. Despotti was in perfect health, not a mark on his body, and sober. Every gondolier he had ever known was a good swimmer. It didn’t make any sense. Gondoliers didn’t drown; it was that simple!

“What does the Fog make of it?” De Sica whispered to Alberto Corrio, nodding his head in the direction of Scampi sitting with Rullo at the stern of the boat.

“You know what he’s like,” answered the exceptionally neat Corrio, straightening his tie as he spoke. “Sooner or later he’ll get us to discover what we didn’t know we knew. Give me one of your Camels. I’ll see if that’ll get him started.”

“Tell me, Corrio,” asked Scampi lighting the cigarette offered him, “what would make a gondolier take his boat to Giudecca, presumably very late at night?”

“Money,” came the quick reply.

“A trip like that wouldn’t come cheap, given what they usually charge for an hour around the city’s canals,” added Rullo.

“A lot of money,” corrected Corrio.

“Where is there always a lot of money on Giudecca?” asked Scampi, this time lifting his voice so that De Sica could hear.

“The Cipriani Hotel,” said the helmsman. “Some of the most famous people in the world stay there, particularly during the film festival, which started last weekend by the way. Right now the city is crowded with stars and directors so you can be sure that most of them are staying at the Cipriani, or at the Hotel Excelsior on the Lido.”

“Good, De Sica. When we land you and Corrio go to the Cipriani and find out if any of their guests hired our gondolier the night before last. Remind the staff that it’s a serious matter so none of their guests can hide behind fame, etc. Find out exactly where the gondolier dropped his client, how much was paid, and why that person didn’t use the special motorboat that ferries all the guests to and from the hotel. Ring Rullo on his mobile when you’re finished. He and I will be at the canal. Oh, De Sica, leave your cigarettes. Nowadays, the rich and famous don’t use camels.”

Arriving at Giudecca, De Sica docked the boat at a wharf directly opposite the tiny island of San Giorgio Maggiore. The wharf belonged to the Guardia di Finanza, an occasional rival of their prestigious military cousins, the Carabinieri. Securing the boat, De Sica and Corrio hurried off to the nearby Cipriani Hotel. Scampi remained aboard, taking his time to enjoy the remains of his cigarette. Rullo was already ashore, pacing up and down, ready to go.

“Patience, Rullo” smiled Scampi, finally stepping from the boat. “This is not a case where the facts might escape before we see them. Now tell me, how is your mother? Still filling you with great food and advice?”

“Yes, Sir,” answered Rullo, trying to avoid thinking about the squid he could be eating. “She tells me every time I go home that being a good policeman is like being a good cook: hours of work for minutes of satisfaction.”

“And your father, what does he have to say on the subject?”

“A good grappa is worth any ordeal!”

“People after my own heart,” laughed Scampi, unaware that Rullo doubted his mother at that precise moment would be interested in Scampi’s heart, unless she had a chance to cook it.

The two men walked down about a third of the long promenade that ran almost the entire length of the island. Naturally, every resident on Giudecca knew about the death of the gondolier, although apparently no one had witnessed a thing. Most of them assumed he was drunk and simply fell in the water. Boats and alcohol were a bad cocktail, was a comment that on the previous day had done the rounds of every bar on the island.

“Here’s the canal, Sir,” said Rullo, “and there’s the gondola.”

“Where did Despotti normally moor his boat for the night?” asked Scampi, interested to see how much of the file Rullo had read.

“In front of San Marco. His family have been gondoliers for generations, so they naturally have the best spot...” Before he could finish speaking his telephone rang. He listened for several minutes, then said, “Yes...yes...yes... I’ll tell him, De Sica...one moment. Sir, the famous actress, Katie Poutlin, hired Despotti to row her across to the Cipriani because she wanted to sit back and look up at the stars. She gave him 400 euro. They left close to midnight, slow-rowed to the island and arrived about twenty minutes later at the hotel’s wharf just down from where we’re moored. He then saw her to her room, where he was invited in, and about an hour or so later he was seen leaving the hotel by one of the night staff. Poutlin is going back to Los Angeles late this afternoon so De Sica wants to know if you have anything else he should ask her. He also said she was very upset about Despotti’s death, and that, in the morning she found her 400 euro hidden under one of her bags.”

A gracious and fair man, our young gondolier, thought Scampi to himself. Aloud he said, “Yes, yes, I can imagine she would be shocked to hear of his death. Tell De Sica to find out if she saw Despotti reboard his boat, and if so what direction he went in, etc. Also, thank her for her cooperation and tell her I’m sorry we had to bring such bad news on the eve of her departure. Regardless whether or not she saw him off, get Corrio to contact the member of the night staff that reported seeing Despotti leave the hotel. Maybe that person also saw which direction the boy headed in after his boat cleared the front of the island. Tell De Sica and Corrio to come down here when they’re through.”

“Yes, Sir,” obeyed Rullo, relaying the orders to De Sica.

“Now, Rullo, let’s go over to that bar and have some lunch. Who knows, maybe one of the regulars has a few ideas that might be helpful?”

The lunch was good, but not the ideas. At the end of their meal Scampi and Rullo decided to have their coffee served outside.

“Busy,” observed Scampi, looking out across the water.

“Yes, Sir. Just about every type of boat in Venice goes along here at some time of the day. Ah, here they are now,” he said a few moments later, looking past Scampi and spying his two colleagues in the distance. “Want some coffee?” he asked when they arrived.

“Maybe later,” answered Corrio checking his reflection in the bar’s window before joining the others at the table. “The actress saw nothing after Despotti had left her room,” he began, before Scampi could ask for a report. “However, the night watchman, Gianni Marcotta, saw him board his boat. He watched him clear the edge of the island and although it was a moonless night he is sure that Despotti was rowing in the direction of San Marco. The last he saw of him before completing his rounds was the silhouette of his gondola about one hundred meters out from the front of the island.”

“Good,” said Scampi. “Now let’s walk over and inspect that gondola.” He led the way to the nearby canal where the sleek, black boat glistened in the early afternoon sun. “De Sica, tell us what you know about gondolas. Just the main points will do.”

De Sica was the fact addict of the team. Speaking about things Venetian gave him a special delight. No man served with the Venice Carabinieri who was prouder of his city than De Sica. From art to antiques, from boats to bridges, he knew it all. He cleared his throat and spoke in his best tour-guide voice. “The gondola is one of the truly unique boats of the world and a fine example of old world knowledge that still impresses expert and novice alike. For instance, it is shorter on one side than the other to compensate for being rowed with only one oar. Its relative short, flat bottom means that it can glide across the water and also spin-turn almost in its own length. Its twisted shape to starboard hides the fact that it is remarkably stable in choppy water. The seven fingers on the silver blade fitted to its bow represent the seven districts of Venice, the six facing forward represent those on the main island, and the one facing backwards is Giudecca. The uppermost part of this silver blade is a cross section of the hat worn by the ancient Doge of Venice...”

“Good, De Sica,” interrupted Scampi. “As you said, a truly unusual boat. Notice anything else that is unusual about this particular gondola?”

“Well, the painting on the crown of the forward bulkhead is better done than most, and the cushions...” De Sica suddenly stopped himself in mid-sentence. “Where’s the oar?” he yelled in excitement. “There’s no oar! Every gondolier leaves his oar on the boat; it’s a matter of tradition. Where’s the oar?!”

“Good, De Sica. Anyone see anything else unusual that might interest us?”

The three young officers stared at the boat. It was securely tied fore-and-aft. Its cushions and seats neatly arranged. Everything seemed to be in order. But they knew Scampi. He never asked a question unless he had seen something. However, stare as they could they saw nothing else of note. The minutes ticked by with no one speaking.

“Okay, let’s leave that for a moment,” said Scampi, breaking the awkward silence. “Anyone got any suggestions as to why the oar is missing, and why the boat is down here, nowhere near the course Despotti originally took on his way back to San Marco?”

More silence.

“Okay, we’ll pick up on all of this back at headquarters. In the meantime, Rullo, you and Corrio go and get De Sica’s boat and bring it back here. Take your time. De Sica and I will sample some of his excellent tobacco.”

“The old man seems almost normal today,” said Corrio, when he and Rullo were some distance away. “The murkier the case, the clearer he is,” he added. “Sometimes I wonder how his mind works, don’t you, Rullo?”

“Who doesn’t? But you have to agree he makes us work our brains. I never saw a thing until I became part of his team. In fact, I often think that if he hasn’t seen it then it probably doesn’t exist!”

Corrio walked in silence, chewing over this comment. Rullo turned his mind back to the squid. Finally arriving at their boat Rullo took the helm and leisurely motored down to where Scampi and De Sica were enjoying the last of the Camels. Eventually the two men boarded the boat and with De Sica now at the helm all four made their way back to their headquarters, not far from Piazza San Marco. Once there, they gathered in Scampi’s office.

Settling into his chair, the other three men grouped around his desk, Scampi buzzed Ito Cossutta and Guido Gazzera. The remaining members of the team, both giants, lurched into the room and stood at attention as Scampi briefed them on what he and his companions had learned from their trip to Giudecca. “At ease; now, tell us what the family had to say,” ordered Scampi. “Just the main points,” he added, aware that the two men tended to elaborate when they had an opportunity. No two officers got more information out of the public than Cossutta and Gazzera, but keeping their reports slender was not their strongest skill.

“As expected, the boy’s parents were in a terrible state,” began Gazzera, “ but after a while the father calmed down long enough to give us some information. So, a little after one-thirty yesterday morning Despotti used his mobile to ring his father to tell him he was just clearing the island and on his way home. Like most gondoliers, Despotti earned good money, but unlike some he was not greedy; it was a matter of professional honor was how his father put it. The son must have told his father about returning the 400 euro. In any case, the family did, however, have one problem. It was a long running dispute involving a neighbour, Giuseppe Gallo. Gallo is originally from Padua and came here to live a few years ago. He is a fisherman and runs a good size boat that he moors at Porto Marghera, a few kilometers North West of the main Island. He lives next door to the Despotti family in Campo Sant’ Angelo and has a small run-about that he uses to take his wife out on the lagoon. He keeps this second boat some distance away in a marina at Porto Campalto, on the mainland behind Venice.”

Cossutta decided to take over the story at this point. “Old man Despotti used to own a typical canal boat, a topa, in beautiful condition judging by the photographs. A while ago he sold it, which meant that the mooring in front of his house was no longer of any use to him. Gallo approached him and asked if he could use the spot, or if Despotti was going to cancel it then to let Gallo know exactly when so he could rush in an application at the appropriate government department and secure the spot before someone else grabbed it.”

“Did Despotti give up the mooring?” asked Scampi.

“Well, not exactly,” answered Gazzera. “He was going to when his son suddenly bought a small boat of his own. The boy’s father therefore decided to keep the mooring in his name and let his son use it. Pretty normal. However, Gallo took it badly. He claimed it was as a deliberate attempt to prevent him, because he was not a Venetian, from having a mooring inside the city. Despotti’s father vehemently denied this as ridiculous, but Gallo would not listen.”

“Is that it?” asked Scampi.

“One more thing,” answered Cossutta. “A little later, Gallo picked a fight with Despotti’s son in a bar all three men were regulars at. The boy side stepped the punch and then left the bar. Apparently, the rest of the bar needled Gallo for not being able to hit the smaller man. That made the fisherman even angrier. Storming out he swore that he would settle the score with the Despotti family at the first opportunity.”

“How long ago was all of this?” asked De Sica.

“Nearly a year,” replied Gazzera.

“What did Despotti’s mother have to say,” suddenly asked Scampi as his men argued over the implications of this news.

“Some fishermen are like the fish they catch,” answered Gazzera, a look of puzzlement on his face.

“What fish does Gallo normally troll for?” asked Scampi.

“Eel.”

“Slippery characters, hard to land,” observed De Sica, making a mental note of another piece of Venetian folklore.

“Good, good, men.” said Scampi. “Now, let’s get back to the matter of the gondola. Why was the oar missing, why was the boat moored in the canal, and what else was odd about the boat? Anyone? No, well, De Sica, Rullo, Corrio, get back to your desks and study the photographs of the boat. Let me know when you see something. Okay.”

“Yes Sir,” said the three men together as they filed out of the office like naughty schoolboys who hadn’t done their homework.

“Gazzera, Cossutta, go and question Gallo about the fight. Nothing else, hear!”

“Yes, Sir,” answered both men as they saluted and took their leave.

Scampi swiveled his chair and stared out of his window into Campo San Zaccaria, the small square adjacent his office. Big crimes committed for little reasons; an old story in Italy. They were always the most interesting cases, but also the saddest. He saw the dead gondolier’s face in his mind. It was such a waste, and for no better reason than convenience and misplaced regional pride. An hour later his meditation was shattered by Rullo screaming at the top of his lungs as he and his two colleagues burst into the office.

“The ropes, the ropes!” yelled Rullo.

“Tell me,” said Scampi, half covering his ears with his hands.

“Two things,” cried De Sica, eager not to be outdone by his colleague.

“You first, Rullo, then you, De Sica,” said Scampi, wondering if Corrio would add anything, hopefully in a softer voice.

“The boat is tied fore-and aft. The only time a gondolier does that is when he’s finished for the day, or when his boat will be unattended for a lengthy period. The rest of the time he ties it amidships so he doesn’t have to climb over his customers in order to cast-off. True, Despotti had finished his day’s work, but he’d already rang his father to say he was coming home, which meant he intended to moor at San Marco, not in Giudecca.”

“But even if he did change his mind,” added De Sica, pleased it was his turn, “the knot used was not the simple reef knot or a clove hitch favored by every gondolier I’ve ever known.”

“Good,” said Scampi. “So what does that tell us?”

“Whoever tied up Despotti’s boat was almost certainly not a gondolier.” said Corrio. “And,” he added, a touch of uncertainty in his voice, “the knot in these photographs, the bowline, is one generally favored by fishermen because it’s stronger and more reliable, although in fairness, other people use it too. However, tying a knot becomes second nature to any professional boatman, something he does without a moment’s thought, particularly in the dark. So, whoever tied that gondola to the mooring rings would automatically use a familiar knot, unless he took time to think about it.”

“Good, Corrio” said Scampi. “And the oar?” he teased. “Why wasn’t the oar with the boat?”

Silence.

“Okay, that’s enough for today. Tonight I want you to think about these crucial points: around one-thirty Despotti is on his way home to San Marco. He rings his father. Sometime between that call and the morning the boy’s gondola is moored in a canal some distance from the hotel, and in the opposite direction to its original course. The person who tied up the boat could be a fisherman, and given what we know about Gallo that places him at the top of our list. During that same period Despotti drowns, and the oar goes missing from his boat. That’s it. See you all in the morning. Think about that oar!”

Several days later, and having heard nothing of interest from any of his men, including Gazzera and Cossutta’s interview with Gallo, except that the fisherman was indeed a slippery character, Scampi decided to change tack. Calling his officers together, he said, “Let us assume that Gallo had a hand in the drowning because of his dispute with the Despotti family. Give me a few ideas about how things might have gone that night. Yes, Corrio, let’s hear it.”

“The time frame we have,” began Corrio, “also covers the period that many of the fishermen come back from their night’s work. Let’s say Gallo is returning to port when he happens to see Despotti rowing in the direction of San Marco. Perhaps Gallo had his deck lights on so he could start tidying up a bit before he got to his mooring. Vessels like his have very powerful lights so they could have caught the gondolier in their glare. Anyway, he sees Despotti, perhaps even speaks to him, and then decides this is the opportunity he has been waiting for. It’s at that point that things become unclear to me,” Corrio modestly admitted.

“Good,” smiled Scampi. “I agree about the deck lights. That is almost certainly how Gallo was able to see Despotti in the first place. Now, anyone else?”

“Well,” offered Rullo, “I’ve been giving a lot of thought to that missing oar. If Gallo rammed the gondola then the force could have knocked Despotti into the water, naturally taking the oar with him as he would have been holding it at the time. The problem is there are no marks anywhere on the gondola to suggest it was rammed, or even slightly bumped. Of course, Gallo could have jumped overboard and once in the water reached up and grabbed the oar, pulling it and Despotti off the boat, but I think that as being highly unlikely.”

“I agree,” said De Sica, “most unlikely. After all, Gallo could lose his own boat, perhaps his life if he did something as stupid as that.”

“True,” agreed Scampi. “So now, finally, we come to the crux of the problem. How do you drown a gondolier, without leaving a mark on him or his boat.”

Much to his own surprise, it was Gazzera who spoke. “Gallo’s a fisherman, so why not just come alongside the gondola, flick the deck lights off, at the same time as throwing a net over the boy and then drag him, along with his oar, into the water. Allowed to play out behind the still moving fishing boat the net would sink below the surface drowning Despotti into the bargain. That could explain why there were no marks on his body, no matter how much he may have struggled to save himself.”

“Of course,” continued Gazzera, “while the net’s doing its work Gallo brings his boat around and grabs the gondola, making it fast to the starboard side of his boat. Turning his boat back toward its original course, he motors across to the island and docks alongside the promenade near the entrance of the Canale Rio Della Croce. He then boards the gondola, unhitches it and works his way along the side of his boat toward its bow, finally pushing off into the canal where he then secures the gondola to the mooring rings. He then steps ashore, re-boards his boat and quietly reels in the net, extracting the body and sliding it over the side. Being a little before first light the water would probably be calm, but I’ll check that, and the tides as well. If the tide had turned and was coming in then that would explain why the body stayed in the vicinity of the canal until it was discovered at dawn.”

“Good,” beamed Scampi. “And the oar?” he quietly added.

It was Cossutta’s turn. “If it got snagged in the net then I’m sure Gallo would have cleared it, if not when he dumped the body then certainly later. If it missed the net then it’s anyone’s guess where it is now.”

“However,” piped in Corrio, “if it was in the net and not discovered until later, then it might still be somewhere aboard Gallo’s boat.”

“If it isn’t,” sighed Rullo, only seconds ahead of De Sica, “then it’s going to be very hard to prove Gallo is our man. The thing that amazes me is not a single person saw anything suspicious that night. I know it happens like that sometimes, but it makes Gallo the luckiest man I’ve ever heard of.”

“Let’s hope we find that oar and his luck runs out,” angrily said De Sica.

It did.

The Fouled Referee

“Maresciallo, do you like soccer?” asked Captain Foscarini. He was experimenting with a softer approach to his second in command.

“Sometimes,” answered Scampi.

Typical Scampi, thought Foscarini, his temper rising. Never get a straight answer about anything. Impenetrable fog, and like all fogs slow moving. He picked up a file and almost threw it at the other man. “Yes, well, see what this is all about,” he snapped, “and look lively about it. And for once, try to curb your natural talent for getting the wrong people off-side. One day one of them will give you a red card and I won’t be able to help you, understand?”

“Yes, Sir,” answered Scampi, admiring the joke at his expense. He choked off his laughter before it had time to surface. Laughter coming from Foscarini’s office could unsettle the entire command. Instead, he gave a crisp salute and then left without further comment. Lately, the Captain’s moods kept shifting from nearly normal to normally nasty. It was probably his new girlfriend. Love had a habit of confusing middle-aged men, particularly those used to giving orders. Scampi put these thoughts away and strolled down the corridor toward his office. Once there he closed the door behind him and placed the file on his desk. Putting off examining it, or even reading the name on its cover, he walked to the window and gazed out at the busy courtyard directly adjacent his office. It was only after the knocking on his door had increased in volume did he snap out of his reverie. He glanced at his watch. Right on time. “Yes, come in,” he said, sitting down and making no effort to appear busy. “Please take a seat, some coffee?” he added as his visitor entered the room.

“No thank-you, Maresciallo, I’ve just finished lunch,” replied Guido Di Martino, the famous reporter for the Gazzetta dello Sport, Italy’s most popular sports newspaper. “Thank-you for seeing me at such short notice. I appreciate you are a busy man so I’ll get straight to the point. The death here in Venice of Carlos Montoya is a terrible loss to European soccer. He was the fairest referee on the circuit and one even the players respected. He will be hard to replace.”

Scampi listened and glanced at the name on the file Foscarini had just given him. Turning his attention back to his visitor he asked, “How may we be of help to you, Signore?”

“I want to ask a special favour,” said Di Martino. “I know that the Carabinieri have a strict policy about not discussing on-going cases with the press, and of course, I respect that. However, on this occasion I was wondering if you might bend the rules a little. My purpose for asking is not self-motivated. Rather, Carlos was not only a fair and just referee; he was also a respected force against the racist muck that has recently soiled the image of soccer. I mean all those hate banners and anti-immigrant signs that have been appearing at matches throughout Europe.”

“How was he a force?” inquired Scampi.

“Three times in this year’s European Cup series,” answered Di Martino, “he stopped a game when those banners appeared. He demanded that they be removed before he would allow the play to resume. His respect was such that in all three matches the players and coaches on both teams supported his call. It was unprecedented in soccer history...I mean for a referee to stop three games in the middle of play! An extraordinary thing to do, and one taking great courage given some of the local and imported soccer hooligans we’ve seen of late. I doubt any other man in European soccer could have gotten away with it. Extraordinary! As I said, his untimely death is a terrible blow to all of us, on and off the field.” Di Martino’s voice trailed away. A barely visible tear appeared in the corner of one eye, but he quickly brushed it away.

Scampi remained silent for a few moments, pretending to be interested in rearranging the one file on his desk. Seeing his visitor had regained his composure he said in a soft voice, “Signore, in memory of a good man I think we can do a bit of rule bending. However, one thing you haven’t told me...why do you want me to bend the rule in the first place?”

“Excuse me, Maresciallo,” apologized Di Martino. “I am asking you to bend a rule while I’m forgetting the most important one of my own profession...get to the facts first! So, I want to get a head start on my colleagues because Montoya’s stand against racism is sure to get lost when the results of your investigations, whatever they are, become public knowledge. Already there are many negative stories about his death. I don’t believe them, but the waters of truth are getting murkier by the hour.”

“Not uncommon when a famous person dies,” said Scampi. “Almost all such stories are baseless, although not always. However, here’s what I will do. In a short while I will be calling my team together. You can attend that initial briefing, and then, when we get to the conclusion of the investigation you can attend the last briefing. Will that be enough?”