Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

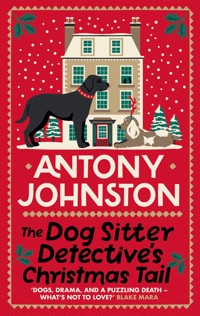

- Herausgeber: Allison & Busby

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Serie: Dog Sitter Detective

- Sprache: Englisch

'Antony Johnson serves up a festive whodunnit that's clever, funny and wonderfully easy to inhale in one sitting. Perfect for anyone who wants their Christmas crime with extra wag' Jo Middleton 'More than one mystery, more than one secret, and definitely more than one dog - this funny, exciting, charming rollercoaster of a book has it all' David Quantick It's almost Christmas, and actress and amateur sleuth Gwinny Tuffel is still pondering what to buy DCI Birch (retired) and whether she could adopt a new furry friend. But sorting through her late father's papers leads her into his mysterious past, pointing to an enigmatic 'liaison' now living in a Somerset commune populated by a group of retired spies. When Gwinny and Birch are unexpectedly snowed in at the remote farmhouse, they find that any skeletons in her father's closet have been joined by a body in the attic. Surrounded by people for whom keeping secrets is second nature, along with an energetic Cocker Spaniel, Gwinny and Birch are embroiled in a murder case once again. Will they uncover the culprit and escape in time for Christmas? Readers love The Dog Sitter Detective's Christmas Tail: 'My three favourite things dogs, books and Christmas.' 'Readers who love Agatha Christie's charm or Richard Osman's humor will find something familiar yet refreshingly light here.' 'Such a fun read!' 'I gulped this tale down-it's that good.' 'Charming and cozy'

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 358

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

123

The Dog Sitter Detective’s Christmas Tail

Antony Johnston

4For all the fake reindeer, dashing through the snow56

CONTENTS

CHAPTER ONE

I stopped suddenly at a market stall, breath misting in the cold winter air. Pretending to browse, I hoped he hadn’t seen me.

My quarry stood barely ten yards away, scanning the packed crowd of shoppers and tourists who jostled and weaved through the Covent Garden Christmas market. Trying to blend in, I stole a glance in his direction. He continued to look around, as if searching for something … or someone. But he showed no sign of recognition. He hadn’t seen me.

With a shrug of his broad shoulders he resumed walking, moving easily among the crowd despite his size. I followed, weaving through the always-changing stream of slow-paced walkers, past people browsing and haggling. My lack of height was both a blessing and a curse; it made me difficult to see amongst all these people, but restricted my own field of vision. He was tall enough to stand out, but if I didn’t keep him in 8sight I might lose him altogether. That was unacceptable.

It was sheer chance I’d spotted him to begin with, browsing the market stalls. Wondering why he was here, I’d debated whether or not to shadow him. It wasn’t why I’d come. But I couldn’t let the chance slip away.

He stopped again, this time taking out his phone. Had someone called him? No, he was making a call. I slipped past two tourist families, hoping to get closer, maybe catch a word or two of his conversation—

My own phone buzzed in my pocket. I removed it, finger already descending towards the Decline button, when I saw who was calling.

It was him.

Should I answer? This could ruin everything … or give me the information I sought. I backed away so he couldn’t hear me above the crowd and tapped Accept.

‘Hello, Birch.’

‘Morning! Wanted to say, um, “break a leg” today. You know, good luck. With the audition.’

My heart melted a little. I wasn’t short of auditions these days, to be honest. My agent was putting me forward for lots of things in order to re-establish my name with casting directors and remind them I was reviving my career, following a ten-year hiatus. Precious few of these auditions led to booking a role, but DCI Alan Birch, retired, called me before each one to wish me luck. Since we’d officially become a couple, he’d opened up a little and become more visibly affectionate.

Nevertheless, we normally made video calls. Not today. 9

‘Thank you, Birch,’ I said, then asked innocently, ‘it sounds quite noisy where you are, what’s going on?’

Leaning through a gap in the market stalls, I spied him looking at the surrounding crowd, trying to think up an excuse.

‘Oh, yes. I’m in … Trafalgar Square. Thought I’d come and see the lights. How about you? Sounds lively.’

‘Carnaby Street,’ I lied. ‘But I’m about to head home.’ I’d actually come here to look for a Christmas gift for Birch, and him fibbing about his whereabouts made me suspect he was doing the same for me. Not that either of us would admit it.

Suddenly the market’s seasonal carol singers began belting out ‘Good King Wenceslas’, their voices travelling up from the basement shopping area and down the phone line.

‘Carol singers at Trafalgar Square,’ Birch blurted, unprompted. ‘Carol singers.’

‘So I can hear.’ I tried not to laugh. ‘I bet they’re freezing.’

‘Bit of a weird echo, actually. Like I can hear them twice …’

‘Oh, um, must be a bad line,’ I said hastily. ‘I should be going. I’ll call you later.’

I ended the call and stayed at the gap, watching him.

‘Can I help you, madam? ’Cos if you’re not buying anything, sling your hook and make way for someone who will.’

The stallholder glared at me, his arms folded. I 10hadn’t really taken in where I was, and now I realised I was blocking anyone else perusing his stall. I looked down and saw shelves of colourful handmade Christmas gifts: Santa ornaments and woodcut reindeer to hang from a tree, felt candy canes, door wreaths made of fabric. It wasn’t my sort of thing, and more importantly it wasn’t Birch’s. What do you get the widowed former Met detective who has everything?

Then I spotted a section of pet gifts and, feeling rather guilty about blocking the man’s stall on a busy morning, picked up a set of fake red antlers made from plastic and felt. I quickly paid the stallholder – rather too much, if you ask me, but that’s Covent Garden for you – then checked through the gap again. Birch was gone.

I pushed through the crowd to the end of the aisle, but it was too late. Wherever my boyfriend (and I was still getting used to thinking of Birch in that context) had moved to next, it was beyond my sight.

Whatever he was getting me would have to remain a surprise. And whatever I was getting him would have to wait for another day; I’d run out of time. I hurried back to the Tube station.

It was quicker to get the Piccadilly Line straight through to South Kensington and walk than change trains twice to reach Sloane Square. Regardless, I speed-marched all the way home to Smithfield Terrace and fell in the door. Well, after opening it with a well-placed kick. It had started sticking a few weeks ago, 11when winter had begun to properly set in. I’d have to get that fixed in the new year.

I’d only just leant back against the door to catch my breath when someone knocked on it, startling me. I didn’t need to look to guess who it would be: the Dowager Lady Ragley, my black-clad next-door neighbour and vigilant defender of the street’s honour. I really didn’t have time for an extended discourse about the ongoing repairs to my house. Could I pretend to be out? No, she must have seen me come in the door to be knocking so quickly afterwards. If I didn’t answer she’d know I was snubbing her.

Still wearing my coat and panting for breath, I opened the door. It stuck six inches in, so I peeked out through the gap.

‘Guinevere, my dear,’ said the dowager with what passed for a smile on her sharp-featured face. ‘Are you well?’

‘Very well, my lady,’ I replied. She’d been a dowager several times longer than her late husband had been a baron, but insisted on being properly addressed. ‘It’s lovely to see you, but I’m in a hurry. I have an audition—’

‘I shan’t keep you,’ she said, with a brief, disapproving glance over my shoulder. ‘You evidently have much work to do.’

Harsh but fair, I supposed. The hallway was no longer filled with my late father’s stacks of old Financial Times newspapers, after I’d finally got most of them to the recycling, but in their place were new stacks of other 12papers, files and magazines that I’d begun to clear out. The house contained decades of my family’s history, and sorting it all out while trying to also have a life of my own was a slow process.

‘Merry Christmas,’ the dowager added, thrusting an envelope at me.

I stared at it, dumbfounded. By the time I found my voice and replied, ‘Um, Merry Christmas …?’ she’d already turned on her heel and gone back inside her own house. The dowager had an uncanny talent for doing so without a sound.

After closing the door with a shove, I finally removed my coat and scarf, dropped the bag with the fake antlers in the kitchen, then carried the envelope through to my lounge. I couldn’t even remember the last time my neighbour had sent a Christmas card. I’d have to write one for her in return, but had no time to think about it right now. I hadn’t even put up any decorations yet. The tree, and its accompanying boxes of tinsel and ornaments, remained in an upstairs room where they’d been since last year. That had been the last Christmas for which my father had been alive, and I’d put the tree up just to make him smile. Without him here, what was the point?

Daydreaming in the middle of the lounge wasn’t getting me anywhere. I left the white envelope unopened on the mantelpiece, knowing that seeing it again later would remind me, and hurried upstairs.

Twenty minutes until the audition; enough time to shower, then set up. It was to be a video call, conducted 13not in a rehearsal space or even a director’s office but ‘remotely’ from my own living room, through the medium of my phone’s camera. I’d grumbled to my agent about this, doubting that anyone would ask Judi Dench to audition via her iPhone, to which he’d replied that Dame Judi wouldn’t be auditioning for a second-tier role with a third-tier director in the first place. Touché.

Frankly, I wasn’t sure I even wanted this role. The director in question was Colin Prendergast, a man with whom I had history, as they say, dating back to when I was a stripling actress in my twenties and he was a rising star. We’d had an altercation which resulted in me being replaced. I’d never worked with him again, and he hadn’t asked me to, for the rest of my career.

That career had ended a little more than ten years ago when I’d retired at the age of fifty to care for my father, after my mother passed away. When he finally joined her a decade later, I discovered he’d left me nothing more than a few grand and this tumbledown old house. So I’d had no choice but to restart my career, which was something of an uphill battle. Good roles for grey-haired sixty-something women were already as rare as hen’s teeth in this world of glamour and bright young things, let alone for someone who’d been out of the spotlight for a decade.

To make ends meet I did a spot of dog sitting on the side, but as much as I loved that, it didn’t bring in anywhere near enough money to repair the house and bring it up to a sellable condition. Not that I had any 14such dog sitting jobs on the calendar at the moment anyway.

All of which meant that if Colin Prendergast was willing to consider me for a role in his new play, A Teardrop of Life, I was willing to bury the hatchet and audition for it. I’ve worked with plenty of similarly belligerent directors, both in TV and on the stage, and work is work.

Fifteen minutes. I had to stop daydreaming and get ready.

Showered and dried, with five minutes to go I prioritised only what they’d be able to see, from the waist up. I tugged a brush through my hair, then threw on a pullover and light scarf to hide my pyjama top. The bottoms, with their pattern of grinning cartoon dog heads, I left uncovered because they’d be out of frame.

Then I took my phone into the lounge, where I spent another minute deciding which background to adopt. I opted for the bookshelves, rather than the front curtains or TV, assuming that would appeal more to a playwright. Finally, I made sure my current half-completed jigsaw was out of sight, opened the curtains for some light, and propped the phone on a pile of books so it was level with my head and shoulders.

I’d already installed the app, and held a practice session with Birch to get to grips with it. If I needed to do anything more than turn on my camera I might be in trouble, but after a couple of taps I was faced 15with a big blue Join button. My finger hovered over it, ready to tap, when I suddenly realised I’d forgotten my sides, which are generally considered handy when auditioning. Silly old Gwinny, where’s your mind these days …

I found the script on the kitchen table, ran back into the lounge, repositioned myself and joined the call. In the three seconds it took to connect I exhaled, reset my expression, and was all smiles when the casting director appeared on screen. Acting!

‘Gwinny, how lovely to see you. I’m Verity, the casting director. I must say, I was surprised when Bostin Jim put you forward. I thought you’d retired years ago.’

‘Bostin’ Jim Austin was my agent, a born-and-bred Brummie (the nickname was apparently local slang). He was a good strategist, landing me small roles and helping me get back up to speed. I quickly re-read my handwritten notes in the top corner of the script, made when Bostin Jim explained the situation to me. An actress had left the play for personal reasons so they needed a swift replacement for the role of Tabitha, a scheming old spinster. Jim said I was perfect for it. ‘How charming,’ I’d replied, but I knew what he meant.

‘I took a short break,’ I said to Verity, keeping up the smile. ‘Now I’m here again. Shall we wait for Colin?’

‘He’s tied up and sends his apologies. But don’t worry, we’re recording all auditions so he can watch them back.’

If he really did ‘send his apologies’, he was a different man from the director I’d known thirty-odd 16years ago. I’d hoped to get the measure of him during this meeting, but it would have to wait.

Verity continued, ‘Let’s start with act two, scene three. From the top, please …’

We ran through the scene, one of the more involved for Tabitha, with Verity reading the other parts. Surprisingly, I was rather nervous. I put it down to doing this online. Prior to my first retirement I’d spent thirty years auditioning everywhere from rehearsal spaces to dressing rooms to basement offices, but always with other people present. The idea of doing it over a computer connection would have struck everyone as absurd. Now, though, the world was quite different. So here I was performing to a propped-up phone in my own front room, and the nerves made me edgy. I knew I was rushing through the lines.

To calm myself I imagined that this was a play within a play, with ‘Gwinny’ just another role I’d already landed, as she now auditioned for a part in the metafictional play. I managed not to daydream myself to pieces, and I think it worked. Besides, a certain amount of nerves is expected and allowed for with any audition. That’s what I told myself.

‘That was wonderful, Gwinny, thank you so much,’ Verity gushed when we finished. She’d have said that even if I stank, of course.

‘Thank you, Verity. I look forward to hearing from you.’ Why I’d suddenly decided to sign off like I was writing a letter to the bank, I didn’t know. Something about the odd nature of being on-screen, perhaps. 17Besides, whether I booked this role or not they’d call Bostin Jim, not me directly. What on earth was I thinking?

Verity gave me an odd look and I panicked. Flustered, I hastily said goodbye and grabbed my phone to end the call, but as I leant forward I knocked the pile of books on which it was propped. The phone promptly fell into my lap, giving Verity an unexpected close-up of my dog pyjamas. When I finally got a grip and turned the screen upright, the last thing I saw was her amused face as she ended the call.

I stared at the black screen, wanting the earth to swallow me up.

CHAPTER TWO

To distract myself from the audition’s disastrous end (and procrastinate the matter of calling Bostin Jim to tell him how it went), I marched upstairs to continue tackling my father’s filing cabinets.

The house’s top floors were mostly used for storage: my parents’ clothes, old dog beds, storage boxes … if it wasn’t regularly used, it had been shoved up here. One small room was effectively an archive of my father’s records. Not an office per se, as there was no desk or chair, but it was filled with filing cabinets, boxes and piles of papers. He had never been the world’s tidiest man, preferring to simply stack new things on top of old things, and I’d put off going through these records for some time. While he was alive there hadn’t been time, as I was too busy caring for him; after he’d gone there seemed little point in rushing, especially as the hallway downstairs had been filled with all those copies of the Financial Times. But I’d finally made a dent in 19those with trips to the recycling centre, and if I was ever going to get this house repaired and sold I’d have to deal with all these too.

I probably shouldn’t have been surprised how far back the files went. Henry Tuffel had worked in the City for most of his adult life, after emigrating to England with his family before the outbreak of World War II, and it really did seem like he’d kept every file and record since. The oldest I’d found so far was a tax return from 1962, though there were many more files and papers from the 1970s onwards. Nobody could see this house without knowing my father was a hoarder, but until now I hadn’t quite realised how deeply ingrained the habit had been.

I’d spent the past week tackling the top three drawers of the cabinet nearest the door, and most of their contents had now joined the piles in the hallway, so now I pulled out its final bottom drawer to begin rifling through it. The drawer made an odd sound while sliding, as if it was catching on something. I closed and re-opened it, hearing the same sound again. I couldn’t see the cause, but it was consistent and seemed to be coming from the back. I pulled all the hanging folders towards the front and peered past the drawer.

There lay a manila folder, curling up from the base to the rear wall, with edges crumpled by the drawer’s movement and paper sheets poking out from inside. The noise I’d heard was the folder being dragged back and forth along the metal runners. It must have fallen out of a higher drawer at some point and become trapped. 20That my father hadn’t noticed or retrieved it suggested how infrequently he’d actually needed these old files.

I stretched beyond the drawer at full reach, took hold of the folder with my fingertips and attempted to pull it out. It resisted, with a bottom corner still wedged in a runner, but after a minute of waggling it finally came free. I flipped the folder open, expecting to find another old financial record ready to toss in the recycling.

But it was much more than that.

I had no idea at the time, but finding this file would begin a cascading series of events that led to murder, exposed secrets and one of the strangest episodes in my life.

The first thing that made the file obviously different from the others was the photograph: a black-and-white picture of a man I didn’t recognise, sitting outdoors at a café. There was no indication of when it had been taken, but his clothes, not to mention the style of the people around him, suggested it was from decades ago. The photo was attached to two sheets of typewritten paper with a clip, so I removed it and flipped it over to check the back. In pencil, someone had written the name ‘Dieter Gerber’.

The name meant nothing to me, and I didn’t recall my father mentioning it. Had he been a business associate of some kind? Why keep a photo of him?

I scanned the typewritten pages, hoping they could furnish an explanation, but came up short. They listed Gerber’s name and vital details – date and place of birth, 21next of kin and so on – followed by a short biography. He’d been born in Munich, then after the war had trained as an engineer in Berlin during its reconstruction. Later he returned to Munich and started an electronics business, Radio Gerber GmbH, which manufactured radio and communications equipment.

None of which my father had ever shown any interest in. How strange.

The file went on to describe Gerber as unmarried and possibly a ‘confirmed bachelor’, an old-fashioned euphemism for gay men, though that wasn’t certain.

Even more strangely, the second page of this odd biography listed places Gerber was known to frequent: his favourite restaurants, commonly visited bars, even the golf club where he was a member.

And there it ended. Or it would have except for two handwritten notes, both in my father’s handwriting. First, in blue ink:

Partial success – contact & interest

Then, in red ink:

cover-up!

C1972

20-31-3

319-23-4

359-14-6, 154-3-10 187-22-7, 404-3-4,

42-18-7 288-12-5 105-24-10

7-16-3 228-10-3?22

When my father had passed away, collapsing in the lounge as he finally succumbed to illness, I was naturally distraught but considered myself lucky to have few regrets. He was, emotionally speaking, a self-sufficient man who tended to deflect questions he considered too personal. But he also enjoyed holding court, so during the decade spent as his full-time carer I’d cajoled him through many conversations I knew I’d otherwise regret not having. He was always willing to expound on his love for my mother, for example, and I certainly made sure he knew that I loved him, despite the days when I could have throttled the stubborn old sod.

But here was a subject I hadn’t even known to ask about, now lost for ever. What had this man Dieter Gerber been to my father? Why had he never come up in conversation? Why was there a file on him tucked away in these filing cabinets, along with a note mentioning a cover-up and a series of random numbers?

Most importantly: were there more?

Ten minutes of quickly rifling through every other drawer in the room furnished an answer to that question. No, this mysterious file was unique.

I scanned it again, noticing something my eyes had passed over on the first read. On the first page, underneath the initial listing of Gerber’s vital statistics, was a single line:

Liaison: Roy Singleton– Telephone 01 9460909

The only date on the file was the line ‘C1972’ in my father’s pen. ‘01’ was an old London dialling code that 23had been obsolete for more than thirty years, so that made sense. And here was another unknown name, someone else my father had never mentioned to me: Roy Singleton.

Was the file my father’s at all? Perhaps someone else had left it here, or it had accidentally been delivered to him, before falling down the back of a cabinet to lie forgotten and undiscovered until now. But there was no doubt my father had made the handwritten notes. I’d recognise his penmanship anywhere.

The thought made me return to the back of the photo, where Dieter Gerber’s name had been written in pencil … but not by my father. It was someone else’s handwriting. So had the picture, and perhaps the whole file, been given to him by someone else? What did ‘Partial success’ and ‘cover-up!’ mean anyway? How I wished I could have asked him.

Perhaps there was someone I could ask, though.

Sitting cross-legged on the floor, surrounded by towers and cabinets of my father’s archives, I took out my phone and tried dialling the ‘liaison’ number on the file.

‘The number you have called was not recognised,’ said the automated woman’s voice from BT. ‘Please check the number and try again.’

Fair enough. I hadn’t expected it would work, given the old dialling code, but I had to try.

Then I had another idea. I swapped out the old dialling code with a modern one, making the number 020 7946 0909. I still didn’t think it would work, of course. 24

But it did.

‘Central,’ said a woman’s voice at the other end of the line.

‘I – well, goodness – sorry, I didn’t think anyone would actually pick up.’ Flabbergasted, I stumbled over my words. Then I checked the name in the file again. ‘Is, um, Roy Singleton available?’

The line suddenly went blank – not the quiet you get when someone simply isn’t speaking, with a little ambient hiss in the background, but the sort of complete silence that normally means the line isn’t working. Or the call has ended.

I was about to put the phone down when the woman returned and said, ‘Mr Singleton hasn’t worked here for some time. Soup of the day?’

What a strange thing to ask. ‘Forgive me, I’m very confused,’ I said. ‘Are you a restaurant?’

The woman paused momentarily – staying on the line, this time – then said, ‘I believe you have the wrong number. Goodbye.’

The line went dead again, and though I waited a full minute, this time she didn’t return. I took a deep breath to regain my wits and redialled, hoping I could get more sense out of her now that I wouldn’t be taken by surprise. Or perhaps someone more helpful would answer.

But this time when I dialled the number, the automated BT voice informed me it was disconnected.

CHAPTER THREE

‘Probably some kind of legacy number,’ suggested Birch when I told him about the phone call that afternoon. ‘Restaurant might not have even known they were paying for it.’

We’d met in Kensington Gardens to walk his black Labrador, Ronnie. Unlike the humans, red-nosed inside our wrappings of winter layers, the dog was oblivious to the cold. He seemed equally oblivious to the idea that other animals might not be quite so insulated, so, despite the frost, continued his usual practice of diving into every bush we passed, hoping to find squirrels wandering about in near-zero temperatures. I once heard Labs described as ‘man’s best friend with the brains of a gnat’, and Ronnie was a fine example.

I’d described the file and my odd phone conversation to Birch as we walked the familiar paths. ‘She didn’t even ask me who I was, or if I wanted to book a table or place an order. What kind of restaurant gives you 26one chance to answer a non sequitur, before putting the phone down on you?’

Birch shrugged. ‘Sounds like the sort of place the Met brass eat at. Not for the likes of you and me, so they vet cold callers. Keep the riff-raff out.’

‘Are you calling me riff-raff?’ I said with a smirk, nudging him.

‘You be riff and I’ll be raff, ma’am.’ He smiled, twitching the ends of his moustache and flashing his bright blue eyes.

Birch and I get funny looks from people when he calls me ‘ma’am’. It’s a habit from the many years he worked under a female police superintendent, of whom I apparently reminded him when we first met. To be fair, at the time I was giving him a dressing-down for not keeping Ronnie under control. I subsequently met the superintendent in question and it’s fair to say we didn’t get on, but then they do say like opposes like.

‘Did you look up the chap in the photo?’ Birch asked.

‘No, I didn’t think of that, I was so surprised by the whole turn of events. I’ll give it a try now.’

I took my phone from my pocket, while Birch took a ball from his to distract Ronnie from chasing phantom squirrels. As he threw it, I searched the internet for ‘Dieter Gerber Radio Munich’.

Predictably, the first page was nothing but ads for radios and links to stores like Argos and Currys. But near the bottom of the second page was a link to a German blog post mentioning someone named Dieter Gerber. I tapped it and was delighted to see the same 27man. The article’s photograph was different to the one in the file, showing a younger Gerber posing, unlike the candid snap I’d seen. But I have an actor’s memory for faces, and was in no doubt it was him.

My German has always been substandard, thanks to my father’s desire to anglicise as much as possible following the war, but I have enough that I could stumble through the blog post and confirm his identity: Dieter Gerber, owner of Radio Gerber GmbH, based in Munich. Reading on, though, I realised this was no simple biography. It seemed to be an account of Gerber’s unexplained disappearance.

‘Look at this, Birch.’ He threw Ronnie’s ball, then turned to my screen. ‘I can’t quite read everything, but this appears to say that Gerber went missing in Munich in 1988 and was never found. How mysterious.’

‘The file you found was from ’72, you said? So he disappeared sixteen years later.’ He peered at my screen. ‘Why can’t you read everything? Need glasses?’

‘No, Birch, because it’s in German. I speak a little, but I’m not fluent.’

‘Oh, easy enough. Here.’ He took my phone, and for a moment I thought he was about to demonstrate a hitherto unknown multilingual ability. Instead, he tapped a few times on the screen, then handed it back. Somehow, the article had changed to English.

‘Built-in translation,’ he explained. ‘Better than nothing.’

I wasn’t entirely sure about that, reading the rather stilted grammar that resulted, but it seemed broadly 28accurate. Further down the page was another big surprise.

‘Good heavens,’ I exclaimed, ‘listen to this. It seems that after Gerber disappeared, his company collapsed and rumours began to emerge that he was a Soviet spy.’

Birch threw Ronnie’s ball again, then shrugged.

‘Plenty around in the eighties. Munich wasn’t a million miles from the Iron Curtain. This is all starting to sound like something out of le Carré,’ he added with a smile.

‘Don’t be ridiculous,’ I said, but smiled along. ‘I just can’t understand how any of this connects. At first I thought Gerber might have been a business associate, but my father was never involved in importing goods or manufacturing.’

‘As far as you know.’

‘It would be an odd secret to keep, though. I’ve found nothing in his files to suggest it, or anything else like the Gerber file. It’s baffling.’

‘Hard to see what it has to do with a restaurant, too.’

‘No, I think you’re right on that one. The number must have been either forwarded or reallocated years ago. The restaurant had nothing to do with it.’ I paused, suddenly confused. ‘Although … then why was it suddenly disconnected when I tried again?’

‘Good question. Want me to look him up?’

‘Who, Gerber? I just did.’

‘Roy Singleton. See if I can find a connection.’ Despite being retired for some years, Birch would always be a copper at heart and maintained contacts in the Met. 29

‘Yes, why not? It’s not the most unique name in the world, but you never know.’

Privately, I thought it would be a small miracle if he could somehow track down the mysterious file’s ‘liaison’ based on nothing but a name and possible connection to my father. But if he did, and assuming Roy Singleton was still alive, I’d jump at the chance to speak with him.

Birch was right that this had begun to sound like a peculiar kind of spy novel. But the idea that my father, a grumpy City trader with a house full of dogs and a permanent tab at Antoine’s, had been in cahoots with a Soviet spy was absurd.

Wasn’t it?

I put my phone away, stood on tiptoe to thank Birch with a kiss on the cheek, then tried to put the matter out of my mind and focus on the moment. That’s what they say these days, isn’t it? Live in the moment. Especially for those of us with fewer moments ahead than behind, it seems like good advice. So I held tight to Birch’s arm, taking in the crisp air and the sight of many others also enjoying the gardens, despite our red noses and flushed cheeks. London in winter can be a harsh place, but at Christmas it becomes quite lovely, even peaceful.

That peace was soon broken by a loud woman’s voice from behind me.

‘Ooh, Gwinny Tuffel? It is you, isn’t it?’

I turned to see a smiling woman in her forties, wearing a red bobble hat and one of those belt 30contraptions with several dog leads attached to it. The leads in question held five dogs, ranging from a sombre German Shepherd to a feisty little Yorkshire Terrier.

Adopting my meet-the-public smile, I said, ‘How do you do? It’s always nice to—’ I’d been about to say meet a fan, but I was saved once again by that memory for faces, which told me she was familiar. I wracked my brains trying to think where I’d met the woman before, then spied the Last Chance Dog Rescue logo embroidered on her gilet and things fell into place. ‘—to run into someone from the rescue again,’ I said, recovering as naturally as I could. ‘You’re in Kensington, aren’t you?’

Last Chance was one of several local dog rescues my father would help out from time to time by fostering. Sometimes they gave him dogs who needed to get used to living in a house with people, before they could hopefully find a new home. Other times they sent brand new arrivals for whom the rescue didn’t have space in their kennels. And sometimes, if we happened to have a dog-free house at that moment (admittedly rare), they sent him dogs that simply didn’t get on with others, so they could live in a place free of conflict.

I say ‘we’, but the truth is it was mostly my father. My mother was fond of dogs, but he was the real soft touch for anything with four paws, and all the local rescues knew it. The house in Chelsea had been a revolving door for all kinds of dogs while I’d been growing up.

That’s why this woman’s face seemed familiar. I seemed to recall she’d been younger and thinner when I 31last saw her, but then hadn’t we all?

‘I’m just getting this lot out of their kennels for a while,’ she replied, indicating the motley crew attached to her waist. ‘My name’s Yvonne. We met before, when you came in with your father. How is he?’

‘No longer with us, I’m afraid. Actually, there’s a thought. Are you looking for donations? Old dog beds, that sort of thing? He left quite a few in the house.’

Yvonne smiled again. ‘Yes, we can always use any spares you have, assuming this one’s got enough?’ She indicated Ronnie, whose ball had been completely forgotten in favour of enthusiastic mutual sniffing with Yvonne’s dogs.

‘Ronnie belongs to my friend Birch, here,’ I said, introducing him. If he’d been wearing a hat he would have doffed it, but he settled for an inclination of the head instead. I continued, ‘Sadly I can’t manage a dog myself at the moment, as it’s just me at home and I’m often out all day working.’

‘That’s right, you’re an actress,’ she said, remembering. ‘But doesn’t that mean you sometimes go a long time between jobs? We have some other actors on our roster, you know. Maybe you could foster when you’re not working.’

‘Um … well, I hadn’t considered it. I’ve actually been dog sitting when I have the time, to keep me afloat—’

‘That’s no problem, we’ll be sure to give you friendlies so you could do both. Fostering’s wonderful, you know, I do it myself with some of the dogs who come through Last Chance, and the rescue pays for 32everything, while you get to bring some happiness to all these poor pooches who’ve got nowhere else to go, and sometimes it’s only for a few days before they’re adopted, although other times they can be there for months, oh, but we can always take them back off your hands if you suddenly get an acting job, and we’d have to do a home check of course, I’ll pop round next week, but I’m sure you’ll pass that with flying colours, it’s mostly a formality to make sure you’re not living in a hole, which I’m sure you’re not, so there’s really no reason at all not to do it, don’t you agree?’

I blinked, taking all this in. A home check? Pass with flying colours? She obviously hadn’t seen my house lately.

‘I’m flattered to be asked, but I’m not sure it would really be a good fit at the moment,’ I said. She looked crestfallen, and the tiny Yorkie suddenly yapped at me as if to say it wasn’t angry, just disappointed. I relented a little. ‘Let me at least think about it, OK? It’s not a decision I’d want to make lightly.’

Her smile returned, and we swapped phone numbers before she resumed her multi-dog walk. Ronnie trotted alongside for a while before he realised we weren’t joining them and hastily returned to Birch’s side.

The former policeman fussed the Lab, then turned his blue eyes on me. Normally I’d consider myself a lucky woman, but at that moment the unspoken question within them irritated me.

‘What?’ I demanded.

He smirked. ‘All this talk of your father. Now by 33chance you meet someone he used to help out, and they offer you a dog? Feels like fate, doesn’t it?’

‘Since when did you become spiritual?’ I replied sceptically. ‘You just want me to get a dog so Ronnie has a companion.’

I hadn’t mentioned it to Yvonne because I didn’t want to give her any more ammunition, but the lack of dog sitting work in my calendar had been preying on my mind. It had dropped off with the turn to winter, as fewer and fewer people went away and thus needed a sitter.

As if summoned by those fickle Fates, at that moment my phone rang with a call from Bostin Jim.

‘Jim, hi,’ I said, before he had a chance to admonish me. ‘Listen, I’m sorry I haven’t called yet, but as soon as the audition was over I got caught up in, um, domestic matters. I promise I was going to call soon.’ I put a finger to my lips, cautioning Birch to be quiet.

‘No problem,’ said Jim, voice booming with his thick Birmingham accent. ‘Verity told me all about how it went.’

My heart sank, imagining the casting director’s retelling of events, but I tried to remain upbeat. ‘Yes, I’m sure she did. Luckily there’s always another audition.’

‘Eh?’ he said, confused. ‘She thought it went very well, despite the technical difficulties.’

Technical difficulties was certainly a generous euphemism for the morning’s wardrobe disaster, but if Verity had said no more, then I wouldn’t elaborate for Jim’s benefit. 34

‘Oh. Well, I suppose it’s fingers crossed, then,’ I said. ‘Assuming Colin wants me.’

‘Don’t see any reason why not. He needs an actor, and you’d suit the role. What more is there to it?’

Bostin Jim Austin was enough of an industry stalwart to know this was nonsense. Show business runs on networking and personalities, and if the director decided for any reason that he didn’t want me, my audition would go straight in the bin regardless of quality. But I appreciated that Jim was trying to keep me thinking positively. We said our goodbyes and ended the call.

‘Heard both sides,’ Birch said. ‘Hard not to. You got the part, then?’

‘Don’t count your chickens. There’s a long way to go from first audition to landing a role.’

‘Still, every step counts. I’ll be there on opening night to cheer you on.’

That was the last thing I wanted. Opening night is often the worst performance of any production, an edgy mixture of nerves, bravado and unfamiliarity. But I couldn’t tell him that. Instead I said, ‘That’s very sweet of you, but how? You can’t leave Ronnie alone all evening.’

He frowned. ‘I’ll give him to a neighbour. Unless you know a good dog sitter I could call?’

I laughed and took his arm as we walked on through the gardens. Perhaps things were looking up after all.

CHAPTER FOUR

Later that week I was halfway down a step ladder, my arms filled with papers and office stationery I’d gathered from a pile on top of a cabinet, when my phone rang.

Torn between going back up and replacing everything on top of the cabinet, or continuing down and putting it all on the floor, I opted for the latter and hurried down the rungs. Which was a mistake, as, in my haste, one foot became caught in the bottom rung and I toppled backwards, dropping everything. Luckily the thick carpet prevented it (and me) from breaking.

Lying on the floor I pulled out my phone, mercifully also unbroken, and saw Birch was calling. I answered voice-only to preserve my dignity.

‘Afternoon, Birch. How are you?’

‘Very well, ma’am. Is everything all right? Can’t see you, for some reason.’ 36

‘It’s fine, I’m just in the middle of something.’

‘Ah, well. Brief it is, then. Called to say we’ve tracked him down.’

‘Sorry, who’s tracked who?’

‘Roy Singleton. The chap from your father’s file. I called a few old colleagues yesterday, and now we’ve got him. At least, seems to be. Same name, same age, retired civil servant.’

‘Birch, that’s extraordinary. How on earth did you do that?’