Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Allison & Busby

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Serie: Lake District Mysteries

- Sprache: Englisch

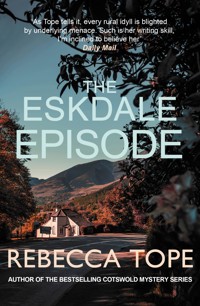

'As Rebecca Tope tells it, every rural idyll is blighted by underlying menace. Such is her writing skill, I'm inclined to believe her' Daily Mail With the approach of autumn, a heavily pregnant Simmy Brown is anticipating the imminent arrival of her new child and juggling the move of her florist business to Keswick. A bouquet order to be delivered to the beautiful but remote Eskdale is an awkward addition to Simmy's to-do list. There she encounters three generations of women - and the next day, one of them is brutally murdered. Drawn into the mystery, Simmy and her friends soon find themselves navigating eccentric artists and fractured families. As her new assistant Evie proves unexpectedly determined to try her hand at sleuthing, and tangled motives begin to surface, Simmy realises the truth is darker than anyone imagined - and closer. And time is running out, in more ways than one. 'A Rebecca Tope novel, be it one of her Lake District, Cotswold or West Country Mysteries is a guarantee of a complex, page turning plot that will keep the reader guessing until the last page. A thoroughly enjoyable read which I heartily recommend.' Mystery People

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 395

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2026

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

3

The Eskdale Episode

Rebecca Tope

4

5

For everyone in my big beautiful family – so many of them!6

Contents

Author’s Note

As with all the titles in this series, the settings are real, but the auction house, the Hartsop home and Venn Farm have all been invented.8

Chapter One

It was the first week of September, nearly five months since Angie Straw’s accident which had brought about several abrupt changes. Simmy was counting down the days until her baby was due to be born, experiencing a bizarre mixture of indolence and urgency.

Her Windermere floristry business had become, as of six weeks ago, a British Red Cross charity shop, and ‘Persimmon Petals’ now occupied a prime position in the middle of Keswick instead. When Angie, Simmy’s mother, had been suddenly rendered unavailable as a childminder, instead needing a lot of care herself, the whole edifice of Simmy’s life as florist and mother had threatened to come crashing down. It took the family a scant week to realise that major adjustments would have to be made. Bonnie Lawson, Simmy’s employee, was the first to voice the unavoidable fact. ‘We can’t go on like this, can we?’ she said. It helped, slightly, that she had said similar things before, but a lot less firmly. ‘It isn’t fair on any of us,’ 10Bonnie added. Her boyfriend, Ben, lived and worked in Keswick, which explained much of her persistence.

It all happened like lightning. The Windermere lease was due for renewal in May. Ben and Bonnie quickly found the empty shop in Keswick. They also found a small attic flat to live in. The stock was moved with a lot less bother than anticipated. The only people to regret the move were Corinne, Bonnie’s foster-mother-turned-landlady, and Verity, who worked in the Windermere shop. ‘I’m not trekking all the way up to bloody Keswick!’ she announced. Nobody had expected her to, but Simmy was sorry to see how upset she was.

Simmy’s husband, Christopher, worked in Keswick. Her parents lived in Threlkeld, barely three miles away. ‘It only needs us to move over to Keswick, and we’d have a real little enclave,’ said Christopher.

‘Over my dead body,’ said Simmy, who loved their converted barn in Hartsop.

But everything was working out extremely well, even if Hartsop was on an outlying limb, down below Ullswater. Angie’s broken femur had given her a few months of feeling unprecedentedly vulnerable and sorry for herself, but she had now recovered almost completely, apart from being unable to drive, and was more than willing to take charge of her little grandson again for at least one day a week, and often two. Her husband, Russell, regularly took Robin, and the dog Cornelia, up Blencathra on foot, or to Castlerigg by car. Angie gave them picnics in the garden or took them to the pub at the bottom of their hill. Robin was two and a half, and not a child to panic. As far as he knew, the world was perfectly trustworthy, albeit sometimes frustrating. He willingly went to his 11childminder, Hattie, three days a week, where two other children had become unofficial siblings for the summer. His parents talked confusingly about a baby, but nothing ever came of their predictions. His mother moved more slowly, but otherwise things went on much as usual.

As a self-employed florist, Simmy had not accorded herself a noticeable maternity leave, despite regular threats to simply lie outside in the sun all day for the final two months of her pregnancy. Resolutions made in the early stages had been abandoned for several reasons. To her secret shame, boredom had been one of them. She had always enjoyed her work, and devoted a lot of her attention to her business. When the move to Keswick had suddenly seemed both feasible and obvious, she developed a powerful commitment to the new shop. She and Bonnie had treated it like a thrilling new adventure, wracking their brains for innovative publicity drives. Simmy found herself more and more determined to make it a success, and to find new avenues to explore. ‘Are you sure?’ Bonnie asked her, whenever she suggested something fresh. ‘Won’t you be much too bogged down with the baby for anything like that? I can still remember you saying you weren’t going to think about work at all after the seventh month, and here you still are, days away from delivering.’

‘I was wrong,’ said Simmy, surprised at herself. ‘It’s bizarre, I know, but I seem to be full of energy. I’m really keen to get cracking on expanding into having a real nursery garden somewhere. That would need to get started next spring, when the baby’s six months old. It can come with me.’

Bonnie puffed out her cheeks, and said nothing.

The loss of Verity had serious implications for their 12flower deliveries, since Bonnie still couldn’t drive. ‘I just can’t seem to get the hang of it,’ she whined, after a few traumatic lessons with Ben. Despite everyone’s insistence that she persevere, the prospect of a licence remained stubbornly far off. Keswick was larger than Windermere, so there were more customers within the town, approachable on foot – but there were still at least a dozen small settlements on every side, approachable only by vehicle.

So when a picture postcard was delivered to the shop on a Monday morning, it caused a degree of consternation. It came in an envelope, with two twenty-pound notes, and read as follows:

Please deliver a dozen yellow roses with added sprays of gypsophila to Miss Jenna Jones at Venn Farm, Eskdale, as early as possible. Payment enclosed. No message required. Thank you. P. O. Williams.

‘Eskdale!’ cried Bonnie. ‘That’s miles away!’

Simmy was holding the card, turning it over to examine the picture on the front. It showed a watercolour painting of a lake – she couldn’t tell which one. ‘We’ll have to do it, I suppose,’ she said. ‘Now they’ve paid.’

‘It takes one hour and eight minutes,’ Bonnie declared, having consulted her phone. ‘It’d be a lot nearer from Windermere.’

‘The gypsophila is no problem, but have we even got a dozen yellow roses?’

‘Just, I think. Possibly only ten. Would that matter? No message is weird. How will she know who they’re from?’

‘Not our worry,’ said Simmy, sounding a lot more 13casual than she felt. Previous experiences with similar commissions had seldom ended well. One woman had hurled the flowers across a farmyard. Others had blanched, or wept, or otherwise manifested negative reactions. But almost always the emotions had arisen from the message and name on the card, rather than the actual flowers. Did P. O. Williams want his (or her?) name mentioned? Apparently not. ‘The money won’t really cover the time and mileage for delivery,’ she calculated.

‘As soon as possible is vague as well,’ Bonnie went on. ‘Do you think tomorrow would be okay?’

‘It’s all horribly vague. Even the address. No postcode. Eskdale’s got those terrible steep roads, hasn’t it? Hardknott and Wrynose – I don’t know which is which, but I don’t want to have to navigate either of them. My car’s brakes aren’t up to it.’

‘If we go at the end of the day, I could come with you,’ Bonnie offered.

Simmy shook her head. ‘No, I can’t be late for Robin. More than two hours late, in fact. That’s not going to work.’

Bonnie was on her phone again. ‘Venn Farm’s not far past the village in the middle of Eskdale. It’s called Boot. Did you know that?’

Simmy shrugged. ‘I might. But I’m sure I’ve never been there. Nobody goes to Eskdale, do they?’

Bonnie laughed. ‘I expect they do. The ones looking for adventure. Let’s have a look and see what we can glean.’

Simmy peered over Bonnie’s shoulder at the little screen, trying to make sense of the map. Before she could start to focus, a customer interrupted, wanting to explain at some length how delighted she was to see the new florist shop. ‘Healthy competition is always a good thing,’ she gushed 14before finally ordering a centrepiece for a birthday lunch.

Simmy shuddered briefly at the implication that existing Keswick florists might well disagree. ‘I’ll go first thing tomorrow,’ she told Bonnie when the woman had gone.

Later that day, Christopher listened not entirely attentively to his wife’s account of the strange order for yellow roses. The flowers themselves were in their little larder, in a bucket of water. ‘Isn’t that rather a long way to go?’ he wondered, refraining from adding in your condition. He steadfastly refused to manifest the slightest anxiety about the coming birth, having readily signed up to the theory that delivering babies was natural and straightforward and seldom a medical matter. Robin had been born easily, as if to prove the point. The fact that Simmy’s first baby, child of her first husband, had been stillborn was something put down to a random stroke of a thoughtless fate, never to be repeated. However, being averagely superstitious, Simmy was doing her best to evade repeating any avoidable patterns from her first pregnancy. For one thing, Tony had insisted they be told the sex of the baby during the ultrasound – which was one reason why she resisted knowing this time. And anyway, she told herself, my whole attitude is totally different now.

Christopher inwardly listened again to what he remembered of Simmy’s words. ‘You can’t get to Eskdale from here,’ he said. ‘Not without going all the way down to Broughton and then back up on that winding road. It must be close to fifty miles.’

‘It can’t be,’ Simmy protested. ‘I thought it would be shorter than going from Keswick.’

‘Let’s see.’ He went to the map of the whole area that 15they had pinned up on the wall. Despite having lived in the Lake District for several years, they both had major blind spots when it came to navigation. Simmy’s father, Russell Straw, was the only member of the family who could find his way around it all. ‘Look.’ Christopher traced the roads with a finger. ‘I was right. There’s no direct road at all. The whole trip’s likely to take you nearly three hours. All morning. Can Bonnie spare you for that long?’

‘So if I go from Keswick, it’s quicker?’ She was still trying to fathom the logistics. ‘Bonnie said an hour and ten minutes, according to Google.’

‘Still not quick. But yes, a much better plan.’

‘I needn’t have brought the flowers home with me, then.’

‘So it would seem.’

‘It’s no wonder I’ve never been to Eskdale. I can’t say I’m exactly keen to go now.’ She gave her husband a look, which he entirely failed to interpret as a plea for advice, or even active assistance. ‘Do you think Ben …? I mean, you’re not really busy this week, are you?’

Ben Harkness worked for Christopher at his auction house, proving himself to be more and more indispensable as time went on. ‘Oh, no!’ was the response. ‘That’s several steps too far. He works for me, not you. And no way is this his problem.’

‘You’re right,’ she conceded. ‘I’m being a wimp.’

He laughed. ‘Haven’t we reversed roles somehow in the last few minutes? I’m supposed to be all clucky and protective, and here I am sending you off into the remotest reaches of mountainous terrain on an errand that seems to have one or two slightly sinister overtones.’

‘And I’m supposed to brush all that aside and set out valiantly to confront the trolls of Eskdale.’

16‘I did point out that you were planning a wholly unsuitable route,’ he defended. ‘And I will remind you to take a phone and a bottle of water and maybe one or two red flags for real emergencies.’

It was getting silly, as they both realised, ending the discussion on a laugh. The coming baby was much more a source of wonder than of any kind of trepidation. Simmy had thrown off all gloomy predictions of exhaustion, veins, heartburn and panic based entirely on her advanced age, and told herself that maturity was an asset. Robin was out of nappies in the day, prodigiously articulate and only fleetingly interested in the prospect of a new sibling. His minder in Pooley Bridge was a miracle of flexibility and good sense, happy to keep him on her books, even if Simmy chose to have him with her while she took time off with the new one. ‘Hattie’s a keeper,’ Simmy often said. ‘We mustn’t upset her.’ They were paying a retainer, which the minder had never actually asked for. Childminders were gold dust, after all. Hadn’t Bonnie been saved by one as a neglected child suffering from severe anorexia, and the blessed Corinne had recommended Hattie, which ensured that everything was perfect.

But still the sheer logistics of the flower delivery to Eskdale were a problem. ‘If you take Robin to Hattie’s, and the dog to Threlkeld, I can leave here at eight, and be at the shop by eleven at the latest, which would be absolutely fine,’ she decided. ‘That girl who answered the job ad isn’t coming for interview until Wednesday now, luckily. I’ll have to be there for that, obviously. I hope she works out – we’ve got to have someone sorted this week or Bonnie’ll be doing everything herself.’

Christopher had already observed that a new employee 17should have been engaged weeks ago, ignoring the complexities involved. Now he just gave an absent-minded nod, and went to brush his teeth. When he came back he said, ‘Why does the dog have to go to Threlkeld? Can’t Lily walk her as usual?’

‘Lily’s gone to a craft fair thing in Nottingham or somewhere. I told you. It finishes today, but she won’t be back till this evening.’

‘Oh.’ The dog was Cornelia, a young black Labrador, who was routinely short-changed by her working owners. She was another individual who would benefit by the arrival of the baby. After a pause, Christopher asked, ‘You do know exactly where to deliver those flowers, I assume.’

‘It’s called Venn Farm. Bonnie found it on her phone, with a postcode. The flower order didn’t give that detail, which was rather unhelpful.’ She went back to the map. ‘Look, it’s not as bad as you said. I’m going to go down to Newby Bridge and approach it from there. There’s only one road, as far as I can see, so I doubt if I can miss it.’

‘Take it steady, then,’ was all he said. ‘At least you’ve got nice weather for it.’ September was, as so often happened, proving a lot more clement than August had been.

Chapter Two

Everything went more or less to plan the next day, although the drive to Eskdale took even longer than anticipated. The shortest route lay through Ambleside, but that involved the infamous Hardknott Pass, where some parts had a gradient of one in three, and Simmy had no intention of attempting that. Instead, she had to go down to Newby Bridge, and then up again via Ulpha and Beckfoot. Her phone confidently navigated her through the first village and then suddenly, with almost no warning, she was driving up onto a great stretch of moorland, the road unfenced and winding. The signs said Ulpha, and eventually Eskdale, so she assumed it was right, but it was not at all what she had envisaged.

When she began to drop down again into Eskdale she found the time to observe how different the landscape was from the Ullswater area. The stone walls were a lot higher, for one thing. And to her surprise there were several fells with generous tree cover on the eastern side. ‘Must tell 19Dad,’ she muttered. Russell was strongly in favour of removing sheep and allowing vegetation to flourish instead.

Venn Farm was a mile or so east of the tiny village of Boot, on the same road as the old Woolpack Inn and the youth hostel. Bright golden gorse lined the road and Herdwick sheep were everywhere, even if apparently not destroying young trees. Large lumps of granite were scattered randomly in fields. Somewhere not far ahead was the vertiginous Pass she had avoided. The farmsteads were spaced out, often with half a mile or more between them, as she drove cautiously along reading their names on gates. The usual pattern was a cluster of substantial stone buildings at the end of a sweeping drive. Tents and camper vans were in abundance. It seemed that almost every farm was providing a field for self-catering campers. Other fields contained a lot of livestock, mainly the Herdwick sheep, interspersed with a few cattle and horses. Peaks rose on both sides, protecting the cultivated land on the lowest available levels. There was a mill and a prettified railway station. A sign showing a steam train caught her eye.

It might be remote, but it was obviously just as popular a holiday spot as any other part of Cumbria. Everywhere gave an impression of prosperity, with a total absence of litter or dereliction. Simmy chastised herself for not coming here before. It had been a serious oversight.

When she found it, Venn Farm had the same long curving driveway, but no indication that it permitted campers. One very small field, near the road, had a high stone wall around it, but Simmy could see that it was full of long grass, nettles and brambles on the parts not strewn with rocks. Amongst the weeds were faded plastic tubes that must have been intended as protectors for baby 20trees. As far as she could tell, nothing was now growing inside them. A failed tree-planting project, apparently. It had been a drier, if cooler, summer than usual and nobody could have watered them, she concluded.

She parked in a dusty yard, and observed that the paintwork on the house was in urgent need of redoing. A purple wheelie bin stood beside a door at one end of the building. Simmy headed for a more central door with a straggly climbing rose beside it, partly anchored to a trellis.

‘Are you Jenna Jones?’ she asked the young woman who came to the door.

‘That’s me,’ came the ready reply and a smile. ‘Who wants me?’

Simmy smiled back and flourished the wrapped flowers. ‘I’ve got a delivery for you. The order came to my shop in Keswick. Yellow roses.’

‘Good God!’

Simmy braced for some sort of extreme reaction that seemed likely to follow from this ejaculation. There was little that would surprise her – tears, rage, sentimental meltdown, a long emotional story or a simple Thanks were all familiar to her. Flowers held more power than she could ever have guessed before she became so involved with them.

‘Mother!’ shouted the woman, turning back to face into the house. ‘Guess what’s just come.’

‘What?’ came a voice.

‘Percy. He’s sent me some roses. Come and see.’

‘Do you mean he’s here?’

‘No, of course he’s not. Just flowers. Like he promised. It’s a message.’ She turned back to Simmy. ‘Do I have to pay you anything?’

21‘Oh no. That’s all seen to.’

Jenna Jones eyed Simmy’s bulk and tipped her chin in a gesture that said Should you be out here looking like that? ‘Do you need a drink or anything?’ she asked.

Before Simmy could reply, a second woman appeared. Looking to be somewhere in her early sixties, she stood in the doorway, holding a large paintbrush like a sceptre. ‘Are they really from Percy?’ she asked, pointing at the flowers. ‘It’s been such a long time.’

‘It has,’ Jenna agreed. ‘But I knew he’d turn up again eventually. We’ll have to go and tell Granny. She’ll be amazed.’ She turned to Simmy. ‘Come in for a bit, and have a drink. It’s quite warm today.’

Simmy was about to refuse, but had second thoughts. ‘Just a quick one,’ she said. ‘I really ought to get back to the shop.’ She was doing calculations in her head, which was her usual reaction when she met multi-generational families. The granny must be pushing ninety, if she was the mother of Jenna’s mum, and if the mum was as old as she looked. The thought of three generations of women living in apparent harmony out here in a half-forgotten land was very appealing. But she was definitely not called upon to make any audible comment to this effect. ‘It’s a long way,’ she added.

‘Did you say Keswick?’ Jenna asked, over her shoulder as she led the way into the house. ‘That’s a good hour and a half from here, assuming you don’t go over the Pass, and even then it’s quite a way.’

Simmy muttered an affirmative murmur. ‘But I came from Hartsop just now. Near Patterdale and Ullswater.’

‘I know Hartsop,’ came the unexpected reply. ‘That’s not at all quicker than coming from Keswick, is it?’ Jenna 22waved Simmy into a low-ceilinged living room, followed by the mother, still holding the paintbrush. ‘Sit down a minute and I’ll get some juice or something. There’s apple, elder, blackcurrant. All home-made. I might have some pear as well.’

‘Apple would be great,’ said Simmy, and Jenna left Simmy in the company of the older woman. The invitation to sit down gave rise to a hesitation. There was a worry that taking a seat would only lead to a longer stay than was advisable. In the end, she perched on the edge of an upholstered chair with wooden arms.

‘Not that any of them are especially easy,’ said the mother, still on the subject of routes over the fells. She seemed to have forgotten the paintbrush in her hand, unless perhaps she was afraid to put it down anywhere. ‘We’re at the end of the earth out here.’

‘It’s lovely, though,’ Simmy assured her. ‘I’m sorry if I’ve interrupted you when you were painting.’ She glanced at the brush. It had a band of yellow paint at the tip.

‘I was patching up an old cupboard. It can wait,’ she said. ‘It’s nice to have a surprise visitor, especially one bringing flowers. We don’t see many people.’ She carefully settled herself onto a small chair, making Simmy aware that she had some kind of back trouble. One shoulder was higher than the other and her neck looked odd.

Simmy felt compelled to keep the conversation going. ‘How long have you been here?’

‘Oh, I was more or less born here. It’s changed drastically, of course, like most places, even the fells in their own way. We’re clinging on, regardless.’

‘You don’t seem to have any camping grounds like the other farms.’

23‘Tried it for a bit,’ said the woman. ‘But the hassle was unbearable. They never stop wanting things. Your life isn’t your own. My mother especially hated it. And she persuaded us it’s economically unviable.’ She waved the paintbrush as if marking a change in her line of thought. ‘We’re more or less self-sufficient now, with fruit trees, eggs and things,’ she finished vaguely. ‘Jenna keeps dreaming up more ways to avoid spending money, which has the full approval of her granny.’ She smiled forbearingly. ‘I’m sure they’re right, but it gets hard at times. The latest idea is to use the car as a generator, instead of being on the national grid, although we’re not sure of the implications for the internet and phone. Jenna’s never going to manage without them. I imagine there’s a chance it’ll work, given that we can charge everything at once and keep it all ticking over, and of course it’s a clever idea, but the reality might not be very comfortable.’ Her hand went to the middle of her back, as if automatically fearing there would be unpleasant physical consequences arising from limited electricity. But she gave a brave smile. ‘We’ve got enormous quantities of firewood for heating and cooking. Very primitive, but Granny loves it all even more than Jenna does. She says it would be just like when she was a child. Oil lamps, candles, a kettle always simmering on the log burner.’ She flicked back a strand of grey hair. ‘It would save an awful lot of money, or so Jenna tells us. And they both think that’s the most important thing.’

‘But not you?’

‘I’m in no position to argue. It’s another four years or more until I get the state pension, and that won’t go very far towards what I’d really like to do.’ She waved an arm 24around the shabby room. ‘A new carpet would cost more than the first month’s payout. And you should see upstairs. It’s even worse than this. It does get depressing sometimes,’ she concluded with a sigh.

Simmy tried to visualise all the implications, making comparisons with her own home. ‘We’ve got a log burner, but we didn’t think to get one with a flat top, so it’s no good for cooking.’

‘Wasteful,’ said the woman.

Jenna came back with a large glass full of cloudy apple juice. Simmy worried that if she drank all of it, she’d need the loo long before she got back to Keswick. ‘I might not finish all that,’ she warned.

‘Your flowers are lovely,’ said Jenna, shrugging away the potential waste of juice. She had put the roses down on a side table, but now gathered them up again. ‘Do you make up the sheaves yourself?’

Was it technically a sheaf, if it only included roses and baby’s breath and a few wisps of feathery leaf, Simmy wondered. She smiled and nodded. ‘Mostly, yes. You were lucky we had yellow roses, actually. We often don’t.’

Jenna sighed and shrugged and held the flowers to her chest. ‘Good old Percy,’ she murmured. ‘I always said he wouldn’t forget to keep in touch. Did he specify that there should be ten?’

‘Actually, no. He asked for twelve. I’m afraid this is all we had.’

‘Ah! Well, I’m glad I asked. It makes a difference.’

Simmy was only mildly curious as to the women’s relationship with the mysterious Percy, but she did wonder at his unorthodox method of ordering the flowers. Just how to pose a pertinent question evaded her, though, and 25she simply drank her juice – finishing it before she could stop herself – and got up to leave.

‘This is a fabulous spot,’ she said, looking out of the window at a fell opposite. ‘I’ve never been over here before. Your mother’s been telling me she’s always lived here.’

‘Generations,’ Jenna confirmed. ‘We’re related to most of the old families in west Cumbria. I think we counted up forty-five cousins and second cousins. Most of them are scattered around the world by now, of course.’

Simmy made a rueful face. ‘I’m impressed. There’s hardly any of us.’ All three looked at the forthcoming addition to the Henderson family. ‘Although I’m doing my best,’ she said with a little laugh.

‘Relatives can be a mixed blessing, believe me,’ said Jenna. ‘And I’ve let the side down completely.’

‘Don’t say that,’ came her mother’s reproach. Jenna ignored her.

Simmy moved towards the door. ‘Thanks very much for the drink. I suppose I should use your loo, if that’s all right?’

There was no immediate consent; after a pause, Jenna led her down a shadowy passageway to a door at the end. ‘It’s a bit of a mess, I’m afraid. But I don’t want to annoy Granny by taking you upstairs.’

The lavatory bowl was stained and the seat was cracked. There were two pairs of wellington boots and some balled-up socks on the floor. There was almost no paper left on the roll she finally found on the windowsill behind her. Thanking her stars that it was summer, requiring minimal clothing, she finished quickly. A very small wash basin was also stained, and the hot tap didn’t work. A hollow breathy sound was all that emerged. The cold was not much better, and there was no towel. This family 26obviously did not go in for anything even approaching modern luxuries – and of course they had not anticipated a visitor.

When she emerged, Simmy noted that Jenna’s mother had disappeared and Jenna herself was hovering near the front door. Simmy took her leave with a hint of reluctance. There was a story here that she would have liked to know. Jenna was about thirty, with a pleasant round face and pink cheeks, resembling her mother in both respects and perhaps her grandmother too. But she, Simmy, would never see them again, never hear about Percy and his promise, and what the roses signified.

Her route lay northwards, all the way to Cockermouth, before using the big A66 to get to Keswick. Within a few yards of Venn Farm was a sign to the village of Boot, and on a whim she turned off. Having come this far, she really ought to give it a look, she told herself, since there was really no desperate need to be back at the shop by any particular time. Within fifty yards, she noticed a sign by a gate saying bamboo canes – free and stopped the car. Bamboo canes were a standard part of equipment in the shop, and the prospect of free ones was impossible to resist. She pulled as far off the little road as she could, got out and went through the gate.

A stone house stood sideways onto the short driveway, and a woman could be seen picking plums in a garden. The fells loomed above a modest clump of oak and sycamore trees. ‘Hello!’ Simmy called.

As if listening for this very shout, the woman came quickly across the lawn to the stone wall between her and Simmy. ‘Yes?’ she said.

‘Bamboo canes. Are there any left?’

27‘Really? I didn’t think anybody would want them so late in the season. How many would you like?’

Here was another ageing female, though perhaps a bit younger than Jenna Jones’s mother. How did anybody end up living in Boot, Simmy wondered. It reminded her slightly of Crookabeck, near her home – a tiny settlement almost entirely given over to holiday lets. And yet people did live there permanently, tending sheep and gardens, working either in one of the bigger towns or remotely from home on computers. Was that the case here, as well? Jenna’s mum had said she was born there, which implied that there were generations of the same family rooted in this spot. How did they all find partners? Did they all have to marry their cousins?

The woman was still waiting for a reply, which Simmy hurriedly provided. ‘I’ve got a florist shop in Keswick. We always need canes for the tall things. I try to avoid plastic if I can. Have you got a dozen or so?’

‘I think at the last count it was over a hundred,’ smiled the woman. ‘I’ve been massacring a very large clump of the stuff that’s been running riot for about twenty years now. It was trying to get under the house.’

‘Oh dear.’

‘Don’t say it – I was mad to plant it in the first place. Lack of imagination, I suppose. I never thought of the consequences. I just wanted to screen out the people in the next house.’ She laughed. ‘At least it worked. I just never dreamt it would spread so much.’

‘Some of them don’t,’ said Simmy, dredging up her bamboo knowledge. ‘You must have been unlucky when you came to choose it. Isn’t it terribly difficult to dig out?’

‘Abominably. I’m using a pickaxe, which does the job, 28but it’s slow. I feel such a beast, as well. It’s not the plant’s fault it’s been so successful.’

Now Simmy laughed, sensing a kindred spirit. In her line of work, she could hardly fail to imbue plants with feelings. ‘I know what you mean,’ she said.

‘Well, can I give you thirty or so? They last for ever. All different lengths and thicknesses.’

‘They won’t root, will they?’

‘They might try – some of them at least. Stick them in boiling water and that’ll stop them. And don’t worry about the colour – they go yellow after a while.’ Belatedly she noticed Simmy’s shape. ‘Can I ask what a heavily pregnant florist is doing out here on a Tuesday morning?’

‘Delivering flowers,’ said Simmy, silently adding, What else?

‘Gracious. Some lucky girl with a birthday, or what?’

Simmy had never found confidentiality much of an issue where work was concerned, but something told her to take care. The mysterious Percy and his minimal method of ordering the flowers had felt decidedly clandestine. As if he had not wanted to leave any kind of trail. ‘Something like that,’ she said.

‘Well, let me get the canes. Where did you leave your car? Or is it a van?’

‘A car. Just out there.’ She pointed.

‘You’ll have them hooting at you. I won’t be long.’

Simmy leant cautiously against a sturdy wooden archway, which had jasmine and honeysuckle entwined all around it, taking some of the weight off her feet. During August her ankles had swollen, and there had been moments of breathlessness, which she took as a sign that she should limit physical exertion. Walking into a garden from her 29car hardly qualified, surely. She had avoided sugary food, alcohol and potatoes and had gained less weight than with Robin. Her back had stood up to the challenge with barely a twinge. She still had all her own teeth. She was in no great hurry for the pregnancy to be over, knowing the infant was easier to manage where it was than out in the world where a mountain of equipment would be brought into play, and nothing would be straightforward.

‘When are you due?’ asked the woman, returning with an armful of odd-coloured canes.

‘Another two weeks at least. I don’t think it’ll be early.’

‘Is it your first?’

‘No.’ The familiar dilemma gripped her. ‘My third, actually, but the first was stillborn.’ This woman could take the facts, she had decided.

‘Ah. I see. I mean – I had a feeling, if that doesn’t sound bonkers.’

Simmy took a slow breath. ‘I can’t believe it shows.’

‘Of course it’s not as simple as that. Call it an aura. Don’t worry about it. Living out here sends us all a bit crazy. Look at it!’ Detaching one arm from the canes, she waved in a half-circle. The scene showed a host of fells ranged all around, bare of trees, rocky and tinged with a faint dusky pink; it could have been an uninhabited landscape from Neolithic times.

‘I’ve never been here before,’ said Simmy, feeling ridiculously small. ‘It’s a lot to take in.’

‘And will you come again? Did you use Hardknott Pass?’

‘I hope I’ll come back soon,’ said Simmy, thinking she still had yet to climb to the top of her own local Hartsop Dodd. ‘I’m going to be rather restricted for a while to come. And no, I couldn’t face the Pass after what I’ve heard.’

30‘You need to have complete confidence in your brakes. The local word for it is outrageous. And yet the satnavs still blithely direct people over it, as if it was just another ordinary road. Most of them must be terrified at what they’ve let themselves in for.’

Simmy laughed and looked at the bamboo. ‘It’s very green,’ she remarked. There were also brown patches and many of the canes were far from straight.

‘Yes, this is the natural colour. But as I say, it fades to yellow before long. It doesn’t matter, does it?’

‘No,’ said Simmy doubtfully.

‘They do the job just as well.’

‘Thank you. It’s very generous of you.’ A vehicle hooted in the road, as the woman had predicted. Simmy clasped the canes awkwardly. ‘I’ll have to go. My name’s Simmy, by the way. Simmy Henderson. It’s short for Persimmon.’

‘Pleased to meet you, Simmy Henderson. And I’m Olive. Also named for a fruit, when you think about it.’

‘Bye, then,’ said Simmy and went back to her car.

Chapter Three

Scafell Pike stood obstructively between her and Keswick, forcing a long curving detour around it, covering twice the distance a determined crow could achieve. The road wavered in all directions as it sought the most level ground. She would have to go due west almost to Seascale before turning north to Cockermouth, along a comparatively ordinary road, and then sharply eastwards along a route that was just like any other. There was even dual carriageway in some places.

The bamboo rattled on the back seat, and she realised she was urgently in need of a loo again barely half an hour after leaving Venn Farm. She found herself in the small town of Gosforth, which had a pub on a corner. Perhaps they were open and would let her use the facilities. There was a car park close by and she turned into it.

The pub was open and willingly allowed her access to the Ladies, seeing her condition. As she came out she 32noticed that a Budgens store across the road was boarded up and a gaping hole could be seen in its roof. Looking round, she gained an impression of a town in decline. A row of houses called Temple Terrace, all painted the same dingy greyish-white, looked ripe for renovation. All three had the same greeny-grey paintwork around windows and doors, and none of them seemed to be inhabited. The pub itself had a tired atmosphere. The only other shop appeared to be a small bakery. Had something happened here, Simmy wondered, to render it so depressed-looking. Seascale, with its unspoilt beach, was close by – as was the nuclear plant at Sellafield, in the process of being shut down. That, she supposed, might explain the slump. Not many of the original employees remained, now that the decommissioning was almost done.

The drive from there to Keswick was straightforward, bypassing Cockermouth and onto familiar territory. It was half past eleven when she finally got to the shop. A few minutes later, she was sitting behind the counter, while Bonnie sold chrysanthemums to a young woman with a corgi. This new shop, unlike the previous one, had a proper counter, with shelves behind it and a display cabinet built in under the top. It had been a wool shop in a previous incarnation.

‘So?’ demanded Bonnie, when the customer had gone.

‘So nothing. It all went perfectly normally. No ructions. The area is absolutely beautiful.’ She sighed. ‘Like a whole other world.’

‘I told Ben last night you were going there. He’s been worrying about you. He says the roads are horrifying.’

‘Well tell him I was fine, and I had more sense than to go the Hardknott way. It was no big deal. I’m back now. 33A woman called Olive gave me a lot of bamboo canes, for good measure. She lives in Boot.’

‘Boot!’ Not for the first time, Bonnie laughed derisively. ‘I still can’t get over that as a name for a village!’

‘I suppose it’s Anglo-Saxon or Viking or something. Or something about boats. It’s quite near the coast.’

‘Ben says there’s a load of good things to see there – old railway stations, a mill, one or two nice churches. He went when he was twelve. And he thinks there’s a castle out there as well. He’d forgotten all about it, and now he wants to go again.’

‘I didn’t see a castle. And I didn’t get to Seascale or see Sellafield. It’s all such a mixture, with neat and tidy farms under the fells, that loom over everything. One of them’s Scafell, although I didn’t notice it especially.’

‘So Jenna Jones is a real person,’ Bonnie persisted.

‘Yes, and she knows Hartsop. That was the only surprise of the morning, really. The flowers were from a chap called Percy, apparently.’ She quickly filled in the few remaining details of her morning, and then settled down with the computer to check stock and send out a few invoices.

But Eskdale continued to nag at her for much of the day. The sheer romance of it was impossible to forget. The brave little settlements, dating back who knew how long, scratching a living from the unpromising soil, until tourism became a thing and salvation lay in visitors from places like New Zealand and Ontario and Argentina, all with their own ideas of mountains and lakes and coastlines that had to be adjusted in the face of Scafell and Wastwater. And then again, there was Jenna Jones and her relations, abjuring the easy money from the tourists and living on the poverty line as a result.

34The baby shifted restlessly, cramped for space as it undoubtedly must be. Simmy knew she had become somewhat bovine in recent weeks, moving more slowly, and not thinking about very much. At night she dreamt she was the woman in Fargo tackling crime while in advanced pregnancy, or perhaps an amalgam of that person and more recent female police officers in TV dramas, rather frequently handicapped by unborn offspring. Pregnant women were expected to function just as usual, ignoring their condition when their work demanded rapid reactions or dangerous heroics. It was all the fault of feminism, Simmy supposed. Babies were a regrettable obstruction to autonomy, the culture was implying, with the result that many women quailed at the prospect and deleted motherhood from their list of priorities. For Simmy herself, there was no contest. Who would ever remember her as vividly as her own children? And what other experience could ever even remotely match that of holding your own newborn infant against your skin?

The fact of a degree of conflict remained, however, as demonstrated by Simmy’s dreams.

It was half past three, and Simmy was preparing to go and collect Robin from Hattie’s, when a man marched into the shop, clearly looking for trouble.

‘I said a dozen yellow roses,’ he shouted. ‘And you sent only ten.’

Percy, said a small voice in Simmy’s head. Turning up in person to complain about a paltry two flowers. She squared her shoulders and faced him. ‘It was all we had.’

‘Not good enough,’ he snapped. ‘Rosie’s going to think I’ve skimped.’

35‘Rosie?’

‘Jenna’s mother, if you must know. She’s always looking for excuses to diminish me in some way.’

Simmy said nothing, trying to reconcile these words with her own impression of the woman she’d met.

‘It was just tough luck that we only had ten,’ put in Bonnie, who had been slow to notice his arrival. ‘If you ask me, you should be thankful we had any at all. Besides, your money was barely enough to cover ten, as well as delivery to the ends of the earth.’

Simmy watched the man’s face as he sought for a reply. He seemed to be in his fifties, with longish colourless hair and wearing a peculiar old-fashioned blazer. His accent was hard to place, but she suspected he might have foreign roots.

‘It had to be a dozen,’ he repeated. ‘She won’t think it means anything otherwise.’

‘I think she did get a message from them,’ Simmy said, hoping to mollify him. ‘I told her you’d asked for twelve. She seemed quite pleased. So did her mother.’ Pleased was perhaps an exaggeration, but there had been no sign of anything negative. ‘I assume she contacted you to say thanks, anyway.’

‘She put a picture on WhatsApp. She doesn’t know I’m in the area. She probably thinks I’m still on Jersey. She hasn’t got any contact details for me.’

So that explained the accent, Simmy thought.

‘But she can WhatsApp you,’ said Bonnie. ‘Surely that counts as contact?’

Simmy pretended to understand how that particular social network operated, but was sadly hazy about the details. All she could manage was a minimal Facebook 36presence and some emailing. She had long passed the point where her ignorance showed any sign of mattering. I can do it if I have to, she insisted, if anybody criticised.

The man shrugged Bonnie’s remark aside and stood his ground. ‘I thought you’d be reliable,’ he grumbled. To Simmy’s ear it sounded encouragingly close to whining, which meant he knew he was losing the argument, such as it was. ‘Now I suppose I’ll have to go and see Jenna for myself.’

‘It’s a lovely road,’ said Simmy brightly. ‘Very scenic.’

‘Oh, I won’t go by road. I’ll have to walk.’ He spoke as if this was a minor inconvenience. ‘It’ll take all day.’

‘How far is it?’ asked Bonnie, eyes wide with shocked admiration.

‘Just over twenty miles, I suppose. Borrowdale, Seatoller, past the tip of Wastwater. I’ve done it before.’ He almost shrugged. ‘September’s one of the best months for it.’

‘You can get a bus as far as Borrowdale,’ said Simmy helpfully.

‘I know you can. It goes all the way to Seatoller, in fact. But I’m not in any hurry. Now I’m here, I might as well make the best of it. Thanks to you, all my plans have changed. I’ll have to face the dreaded Kate, for one thing.’

Simmy wasn’t sure whether or not he was complaining. There was a suggestion that the new plans might in fact be an improvement. ‘Well, I’m sorry about the missing flowers, but we did our best in the circumstances. It was rather an unusual order, after all.’

He shook his head. ‘I don’t see why. Real money, clear instructions. What more do you need?’

Simmy found nothing to say to this, and there was an uncomfortable silence. Bonnie had drifted away, leaving 37the man to Simmy once she’d concluded he was no threat. He had paid no attention to the pregnancy, barely looking directly at either of them. A customer broke the awkward paralysis that had come over all three, and Percy Williams took his leave.

‘He’s an odd one, isn’t he?’ said Bonnie, when they were alone again.

‘At least he didn’t ask for a refund. I thought he was going to.’

‘I was wondering why he came in, actually. I suppose he just wanted to shout at somebody. Men can be like that,’ she added, with a knowing look.

Simmy laughed. ‘I’ve been trying to think of all the ways he might be connected to Jenna in Eskdale. I got the impression he must be a relative, rather than a boyfriend. He’s much too old for that, anyway. I mean, too old for Jenna, and too young for her mother. There’s hardly anything to go on, except they apparently use flowers to send messages.’