7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Orenda Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

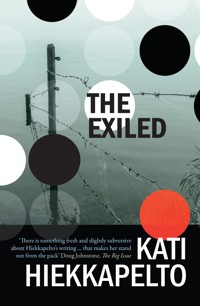

When Finnish police investigator Anna Fekete's bag is stolen on holiday in the Balkan village of her birth, she is pulled into a murder investigation that becomes increasingly dangerous … and personal. The electrifying third book in the international, bestselling Anna Fekete series. ***Shortlisted for the Petrona Award for Best Scandinavian Crime Novel of the Year*** 'Tough and powerful crime fiction' Publishers Weekly 'A gut-punch of a book' Metro 'Dark-souled but clear-eyed, Kati Hiekkapelto's edgy, powerful novels grip your throat and squeeze your heart. Addictive' A J Finn, author of The Woman in the Window –––––––––––––––––––––––– Anna Fekete returns to the Balkan village of her birth for a relaxing summer holiday. But when her bag is stolen and the thief is found dead on the banks of the river, Anna is pulled into a murder case. Her investigation leads straight to her own family and to closely guarded secrets concealing a horrendous travesty of justice that threatens them all. As layer after layer of corruption, deceit and guilt are revealed, Anna is caught up in the refugee crisis spreading across Europe. How long before everything explodes? Chilling, tense and relevant, The Exiled is an electrifying, unputdownable thriller from one of Finland's most celebrated crime writers. –––––––––––––––––––––––– 'Finnish Kati Hiekkapelto deserves her growing reputation as her individual writing identity is subtly unlike that of her colleagues' Barry Forshaw, Financial Times 'The Exiled represents the next level in creative development of both the author and her heroine. There is the subtle confident maturity: the writer who is not afraid to challenge the current political and social situation, and to rage about it in the most elegant literary manner, and the character who learns more about her roots and her personality, and ways to deal with the feeling of displacement' Crime Review 'Compelling, assured and gutsy … a gripping and stimulating read' LoveReading 'There is something fresh and slightly subversive about Hiekkapelto's writing … that makes the novel stand out from the pack' Doug Johnstone, Big Issue 'An edgy and insightful chiller with a raw and brooding narrative. Skilfully plotted and beautifully written, Hiekkapelto has given us an excellent and suspenseful crime novel' Craig Robertson 'A beautifully written and many-layered mystery novel that illuminates the dangers of prejudice, while still providing a major thrill ride' Mystery Scene Magazine 'A taut and provocative thriller with a raging social conscience' Eva Dolan 'A writer willing to take risks with her work' Sarah Ward 'The taut and elegance of the writing brilliantly contrasts with the grit of the subject matter' Anya Lipska

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 447

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Ähnliche

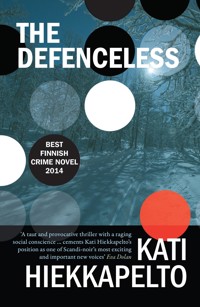

PRAISE FOR KATI HIEKKAPELTO

‘An edgy and insightful chiller with a raw and brooding narrative. Skilfully plotted and beautifully written, Hiekkapelto has given us an excellent and suspenseful crime novel’ Craig Robertson

‘Kati Hiekkapelto deserves her growing reputation, as her individual writing identity is subtly unlike that of her colleagues … her socially committed style acquires more polish with each successive book’ Barry Forshaw

‘Seriously good! The taut elegance of the writing brilliantly contrasts the grit of the subject matter. Kati Hiekkapelto is the real deal’ Anya Lipska

‘There is something fresh and slightly subversive about Hiekkapelto’s writing … that makes the novel stand out from the pack’ Doug Johnstone, The Big Issue

‘Crisp and refreshing, with a rawness that comes from a writer willing to take risks with her work’ Sarah Ward, CrimePieces

‘A gripping slice of Scandi Noir’ Raven Crime Reads

‘Hiekkapelto’s particular type of crime genre is deeply intertwined with social critique, as was already evident in The Defenceless. This is a happy marriage, and she manages to discuss touchy and topical issues such as immigration without succumbing into the dangers of holier-than-thou territory. For me, however, this was a book about Anna’ One Day I Will Read

‘Chilling, disturbing and terrifyingly believable, The Defenceless is an extraordinary, vivid and gripping thriller by one of the most exciting new voices in crime fiction’ Northern Crime

‘Kati Hiekkapelto’s second novel has fully delivered on all of the promise of her first. The Defenceless is a gritty crime novel with a pulsing vein of social realism. It is entertainment with a conscience, fiction with heart-rending insight into the real lives of people on the fringes of our own societies’ Live Many Lives

‘From the outset The Defenceless ticks so many of the boxes that Scandinavian crime fiction lovers look for in their favourite crime sub-genre, and here’s why … The real stand-out feature of this book is the strength and balance of Hiekkapelto’s plotting. A gripping slice of Scandi-noir’ Raven Crime Reads

‘In her follow-up novel, Kati Hiekkapelto weaves a complex, multilayered narrative that forces the reader to re-evaluate long-standing opinions. More strident than its predecessor, the book uses the crime fiction genre to shine a torch on to under-reported social problems.’ Andy Lawrence, Crime Time

‘With The Defenceless you’re so caught up in the characters, the sub plots and the hunt for what appears to be a brutal killer that when the killer’s identity and motive are revealed it comes like a bolt from the blue. It brings to (my) mind the reveal in Håkan Nesser’s The Unlucky Lottery. The translation – by David Hackston – should also receive the strongest nod of approval; at no point in reading The Defenceless was there any indication that this was anything other than the language the novel was written in, and the deft translation ensures that the novel’s momentum and feel flows uninterpreted across the language transition’ Tony Hill, Mumbling About Music

‘The Defenceless is a powerful read, tackling illegal immigration and the role of gang members in exacerbating the desperation of migrant workers. Hiekkapelto is unflinching in her chilling descriptions and, once more, it is her police investigator protagonist, Anna Fekete, who dominates the narrative’ Sarah J. Ward, Crime Pieces

The Exiled

KATI HIEKKAPELTO

Translated from the Finnish by David Hackston

To my mother

Contents

JUNE 19th

Droplets of blood on the light-green wallpaper, like overgrown poppies along the verge.

Here, where the hazy grey sky swallows the edges of the immense wheat fields, where you can sense the Tisza, the river flowing past, even when you can’t see it. The river is always present, always on the move, arriving, leaving. It flows like a giant artery through the poisoned fields, where weeds, poppies, cornflowers and dandelions are stifled and beaten back, past this small town where life feels unchanged, where time seems to have stopped while the country around it changes name, fights wars, languishes on the precipice of economic collapse, harbours its war criminals, ashamed of itself but too proud to admit its own mistakes. That country contains dozens of identities, nationalities, minorities, majorities, languages. It has signed the UN Declaration of Human Rights but doesn’t uphold its contents.

The river will come into blossom any day now. People are saying it will be the biggest flowering in living memory. Perhaps right now millions of mayfly larvae are beginning to hatch and dig their way out of the mud on the riverbank. Soon they will swarm above the river like a giant, beautiful cloud of flying flowers; they will mate, lay eggs and die. People gather along the riverbank to celebrate, many taking their boats out on the water, in among the insects, so they can feel the delicate beating of their wings and the touch of the insects’ rubbery bodies on their skin. The flowering is a wondrous carnival of life and death, an event the town eagerly awaits and that people celebrate with great verve. Nothing like this happens anywhere else in the world – only at this bend in the river, at the centre of this town. As though the town was special, blessed.

Droplets of blood. They converge on the light-green wallpaper into a large, blackening pattern, a giant amoeba. The wall is around two-and-a-half metres high, five metres in length, and behind it is one of the house’s two bedrooms. The wall is bare – no paintings, no mirrors. Only plain, light-green wallpaper, and now that pattern in the middle, the amoeba, the poppy field.

A moment earlier a figure cast a shadow as he sat down at the antique desk by the window. The desk was bare; it had just been cleared, its drawers emptied. From outside came the sound of footsteps, the happy laughter of children walking past, laughter that seemed out of place in the atmosphere of the room.

A road leads directly past this house. In this part of town all the houses are built like this, snuggly against one another and so close to the road that they form a wall along the narrow pavement. A cherry tree can be seen through the window. It stands on a small strip of grass between the road and the pavement, its leafy branches shading the house so well that the occupants rarely need to lower the blinds, though the afternoon sun shines mercilessly on this side of the building. The blinds in this window are drawn last of all, in a futile attempt to hold back the heat when the summer outside is so sweltering, so oppressive that it penetrates everything. The branches are heavy with cherries – dark-red, juicy globes, ripe and ready to be plucked. Will anyone pick them this summer, preserve them in syrup, organise the jars in rows on the shelves in the pantry behind the kitchen?

A moment longer after he sat down, then his head and body worked together. The sturdy barrel of the pistol was placed squarely beneath his jaw, at such an angle that the bullet would go right through his skull and not just injure his face, leaving him alive but in pain. The pistol was loaded, his hand wasn’t trembling in the slightest, his body was steady and prepared. With one exception, his head always had perfect control over his hand and pistol.

A shot, and before that a single thought: hell is here. Right now.

JUNE 3rd

THERE WAS A SMALL WINE FESTIVAL going on in the park outside the town hall. To Anna the word ‘park’ seemed a bit over the top for the green but rather underwhelming strip of land, bordered to the south by the town hall and to the east by the road running between Horgos and Törökkanizsa, which pared off a chunk of the town. At the northern end of the park was the main shopping boulevard, and to the west rose the beautiful belfry of the Orthodox cathedral. The area was barely a quarter of a hectare in size, nothing but a stretch of lawn shaded by the chestnut trees right in the centre of Kanizsa. In the summer people sat in the shade of the trees watching the passers-by, keeping an eye on their playing children and exchanging gossip. In the evenings the place was filled with youngsters. Fine, call it a park, thought Anna. After all, it even had the obligatory statues – busts of two local artists and a monument to commemorate the Second World War. Za slobodu, it read in Serbian. In the Name of Freedom. The park was as tenuous as the freedom that existed in this country. A semi-park. A semi-freedom. Anna wondered how she might translate those words into Hungarian. She couldn’t think of anything. Word play worked better in Finnish, and in Finland the notion of freedom seemed to grow more absurd by the day.

The evening had grown dusky. Light bulbs dangling from the trees like strings of pearls lit the asphalted path running through the park. The path was lined with wine-tasting stalls, tables and chairs. People crowded around them, drinking and laughing. Acquaintances and half-acquaintances, and even some complete strangers, who must have been friends of Anna’s mother, stopped as they saw Anna and greeted her with smacking kisses on both her cheeks. Anna could smell the wine and tobacco on their breath as they went through the list of compulsory questions, excited and apparently with genuine curiosity. How are you doing? When did you arrive? How long will you be staying? Did you fly into Budapest? How long is the flight? I’m sorry about your grandmother. She was a good woman. Oh, you didn’t make it to the funeral? Your brother has been here for a while now. How is he getting on? And how is your mother keeping? You must come and visit one day, any time you like. Finally they whispered to Anna, almost apologetically, that last year’s fair had attracted many more people. What a shame it’s so quiet this year. It’s started straight away, thought Anna: the apologising. Had people apologised like this back in Tito’s day? Or had it only started after the war that led to the break-up of Yugoslavia? It seemed that a sense of inferiority had descended over Kanizsa like a veil, a layer of dust in an abandoned house. But the locals barely noticed it. Here, complaining about things and belittling themselves were an integral part of communication, and nobody thought of the effect this had on the atmosphere and on people’s confidence and self-respect. People were slowly but surely giving up. Anna had sensed this in the past too.

Anna thought there were a surprising number of people at the fair. After the scorching daytime heat the evening was still warm, and a hint of approaching rain hung in the air. People weaved around one another and the atmosphere was almost jubilant. On a stage erected at one end of the path a band struck up and started playing covers of Hungarian hit songs; the music was so loud it could probably be heard on the other side of town. Inferiority complex or not, at least people here knew how to celebrate, how to live in the moment, and the following morning nobody, not even the grumpiest old codgers in town, would complain about being kept awake by the noise. They were all probably enjoying the party too, asking their grandchildren to bring them little tasters of the different wines.

In front of the stage a group of youngsters were slouching around, bottles of beer in their hands, and more people were arriving all the while. Anna felt tired. To tell the truth, she’d wanted to go to sleep a long time ago, or at least to withdraw into the peace and quiet of her bedroom. All the greetings, the shrieks of excitement, the kisses on the cheek and the questions about how she was doing had quickly got on her nerves. In Finland she forgot all about the inquisitiveness of the people of Kanizsa, so gushing it was almost overwhelming, and after the first few days of her holiday it always managed to exhaust her. She instantly started making comparisons in her mind: in Finland people do this and that instead. It annoyed her. It was as though she was constantly awarding each place plusses and minuses, as though this would help her decide where she belonged. As though she had to make a choice. But she didn’t. Fate had made that decision for her long ago.

Anna had arrived in Kanizsa late in the afternoon. After a bad night’s sleep she had set off ridiculously early from her one-bedroom rented apartment in Koivuharju, taken a cab to the airport, flown south to Helsinki and caught a connecting flight to Budapest. There she had jumped into a hire car – a white Fiat Punto with automatic gears and with such efficient air conditioning that she could still feel the chill in her shoulders – and driven a few hundred kilometres directly south. She crossed the border at Röszke, taking a deep breath once she arrived on the other side, where the Hungarian steppe, the puszta, stretched out on both sides of the road like the open sea. A few kilometres later she turned right at the intersection leading to Horgos, where the houses looked like they might fall down at any minute, and then to Magyarkanizsa, which the locals referred to simply as Kanizsa.

The transition was too quick. It was like this every time. When a plane shoots into the sky and hurtles through the air at hundreds of kilometres per hour, carrying people from one city and one country to another, the soul has no time to catch up. Its habit is to unwind itself slowly, at its own pace. Anna knew this perfectly well, but she never seemed able to protect herself against the shock; she always went straight to Kanizsa to visit friends as soon as she’d arrived. Instantly she became so agitated that she almost hated the place, regretted ever coming back and felt as though she was suffocating inside her own soulless body, as though it was the soul – the innermost being – that defined the extremities of our body and protected it from outside attacks. It was a strange feeling but one that would soon pass. She knew that too.

They sat down in front of a stall belonging to the Nagy-Sagmeister vineyard and bought three bottles of wine and one of mineral water. Anna was with friends she had known since they were at nursery school together: Tibor, Nóra, Ernő and Véra. Réka hadn’t joined them. She’d been feeling ill all day, and she and Anna had agreed to meet up tomorrow. Anna’s mouth felt bone dry after the long journey, and she downed a large glass of water. Her friends handed her a glass of white wine – furmint – which the local vineyard had bottled the previous autumn. This stuff’s fantastic, top notch, they assured her. You won’t find anything better in Hungary either. This producer – a Kanizsa local – was set to bring Serbian wine culture to new heights, they proudly proclaimed. Anna sipped the wine. It was good. She watched the people walking past and noticed a man standing at another stall with a glass in his hand, looking over at her. For a moment Anna looked elsewhere and nodded at Tibor’s stories as if she were actually listening to him, then she cautiously glanced back at the man. Yes. Now he was openly staring at her. Anna awkwardly looked down at her wine glass.

‘Don’t look now, but who is that man over there on the left? The one with the bespoke suit and the grey hair,’ Anna asked Nóra.

Nóra peered over Anna’s shoulder. The man was engaged in conversation with the owner of the wine stall.

‘That’s Remete Mihály. He sits on the local council. He’s a big fish. Apparently he’s going to run for parliament at the next election.’

Again the man looked over at Anna.

‘He’s staring at me,’ said Anna and felt an uncomfortable tingling sensation in her back.

‘Mihály likes younger women. It’s an open secret round the town,’ said Tibor and gave Anna a teasing nudge on the shoulder.

‘He’s old enough to be my father,’ Anna scoffed.

The man paid for his wine and began walking towards their table.

‘Damn it, he’s coming this way,’ Anna whispered.

‘Jó estét kívánok, Remete Mihály vagyok.’ The man stood smiling in front of Anna and held out his hand.

Anna shook his hand and introduced herself. The man had several thick golden rings on his fingers.

‘I know who you are,’ he said ‘I knew your father well. He was a good man.’

Of course, thought Anna. Everybody had known her father. Back here she would always be her father’s daughter. This defined her position in a society to which she no longer belonged, but to which she was eternally bound. Her grandfather, grandmother and great-grandfather were roots, and her mother and father the trunk from which her own branch grew. She could almost see that branch appearing like a speech bubble in a cartoon as the local man tried to place her in the right bough of the right tree in the arboretum called Kanizsa. A sense of relief flashed across their faces when they found the correct tree, the correct branch. Good. You’re not an outsider. We know you. We know how to treat you.

How ludicrously wrong they were.

‘Are you here on holiday?’ asked Remete Mihály.

Anna repeated the same things again, answered the same questions, smiled and raised her wine glass when the man decided to make a toast to her father.

‘Come and visit me some day,’ he said. ‘I could show you a few photographs of your father from when we were young. You might be surprised. We were a pair of tearaways.’ At that he gave a hollow chuckle, bade the group good evening and went to the next stall to get another glass of wine.

‘Nice guy,’ said Ernő. ‘I voted for him last time.’

Anna could hear Ernő beginning to slur his words. Nóra wanted to take the obligatory selfie with Anna and their glasses of wine and upload it to Facebook straight away. Anna put on a smile and posed for the photo: cheek-to-cheek with Nóra, cheese; and with our glasses raised, cheese; now with the guys. The prodigal daughter has returned, Nóra typed and tagged them in the photograph. She giggled at her own inventiveness and wondered out loud why Anna still wasn’t on Facebook. Anna explained – for the umpteenth time – that she simply didn’t want to. Eventually she said she might consider it in order to keep in closer contact with her old friends, but only because Nóra’s effusive Facebook sermon started to make her feel pressured.

The guys’ conversation had shifted to local politics, a subject about which they both seemed to have trenchant views, while the women chatted about their work and what they had cooked for dinner earlier that day, yesterday, last week. Anna tried to engage in her friends’ conversations but couldn’t get a grip on the rhythms, couldn’t deploy appropriate words at the appropriate moment, and didn’t really know what to say about either subject. After a while she gave up and listened to the buzz of chatter, punctuated with bursts of laughter. Before long she’d given up on that too. She drifted into her own thoughts, sensed the dizzying smell of the hársfa in her nostrils, closed her eyes for a moment and slowly began to relax. Things will be fine, she thought. I can soon go to bed, they’ll understand I’m tired. Tomorrow this will all feel much nicer, much cosier, and I’ll see Réka for the first time in ages. We can go for a walk across the járás.

Just then Anna felt a violent shove at her back. She was buffeted against the table – so hard that Tibor’s wine glass toppled over. Golden-yellow furmint trickled over the edge of the table on to the ground and splashed on Anna’s trousers. Tibor leapt to his feet and shouted something, and it was then that Anna noticed her handbag had disappeared from the chair next to her.

‘My handbag!’ she shouted. ‘Someone’s taken my handbag!’

Tibor and Ernő dashed into the crowd of people.

‘Stop! Thief!’ Tibor hollered. It sounded almost like a joke, like something straight out of a cartoon strip.

Anna rushed after them. She saw someone running. The figure disappeared into the crowd, reappearing a moment later at the edge of the park. The situation had erupted so unexpectedly that nobody had time to react. Anna barged past people standing in her way, and when she eventually reached the pathway, she caught a glimpse of two people running in different directions: a man, and a little girl in a red skirt, who swiftly slipped away among the high-rise apartment blocks rising up behind the Orthodox cathedral. The man was running towards the school. Each of them carried a bag.

For a fraction of a second Anna considered which of them to run after. She chose the man. Ernő, who was in much poorer physical shape than Tibor – he had put on weight and smoked like a chimney – had run off in the same direction, but there was no chance of him catching up with the thief on foot. Tibor was heading down the main road after the girl.

The man was already running past the school and now disappeared round the side of the building. Anna couldn’t see whether the bag in his hands belonged to her. She increased her pace and sped past Ernő, who by now was gasping for breath, ran round the corner of the darkened school and reached the next road. From there she could see the cathedral and as far down as Kőrös, but the fleeing man had disappeared from sight. Anna came to a halt at the intersection and listened. Normally it would have been easy to follow the echo of footsteps in the otherwise quiet town, but now the boom of music from the park drowned out all other sounds. A barn owl leapt from the cathedral copula and glided into a silent hunting flight. Its pale silhouette disappeared behind the tall chestnut trees. Ernő finally caught up with Anna.

‘Where did he go?’ he asked, panting loudly. He rested his hands against his knees and grimaced.

‘I don’t know,’ Anna replied. ‘It’s no use standing around wondering about it. I’ll go that way, towards Sumadija utca. Go and check round the church, maybe he’s hiding somewhere, lying low in the rose bushes round the corner.’

‘What shall I do if I find him?’ asked Ernő.

‘Catch him.’

‘How?’ Fear flashed across Ernő’s eyes. Fear and uncertainty.

Anna didn’t answer. This wasn’t the time for a lesson in apprehending a suspect. She took off her high-heeled shoes and jogged off briskly – barefoot and almost silent – down Sumadija utca, past the nursery school, hoping she would be the one to find the man and not Ernő. The darkness thickened around her. Small sharp stones pricked the soles of her feet, but Anna didn’t care. One of the aims of rigorous exercise was to get used to pain, and Anna was a master of that. Be that as it may, she hoped she didn’t step on a broken bottle. Even she had limits.

The sound of the music had died down, or perhaps the band was having a break. Streetlamps were few and far between, and there were no cars in the street. Kőrös looked all but deserted. This area to the north of Kanizsa had once been at the bottom of a lake. Back when the Yugoslav economy was booming, it had been built up into a middle-class residential area with two-and three-storey houses standing tall and silent, each in their own fenced-off garden. The empty, almost ghostlike feeling was heightened by the heavy shutters pulled across the windows, making the buildings look dark and abandoned. What’s more, each building had its own garage, so there were no cars parked out on the street. Nowadays few people could afford to keep these enormous houses heated during the winter months. As the price of imported Russian gas had skyrocketed, the upper floors of these apartment blocks were often left unheated all winter, and in a house with six rooms, people sometimes heated only two: the kitchen and the living room.

At the Szent János crossroads Anna again had to make a snap decision about which direction to take. She listened to the silent streets for the space of a long, deep breath. For no logical reason she decided to run towards the Gong restaurant and took the first left on to Szőlö utca. All of a sudden a metallic gate gave a clatter right next to her, as though something was trying to clamber through it. Anna gave a startled shout, and on the other side of the fence a mongrel with a tangled coat ran alongside her barking wildly.

‘Quiet!’ Anna snapped at the dog, which stood at the corner of the garden barking after her. Now they’ll know for sure where I am, she sighed, and at the next crossroads slipped into Tvirnicka utca. She jogged up and down the streets. Small, sharp stones cut into her feet, tore a hole in one of her socks and scratched her heel, but still the thief was nowhere to be found.

When she saw Ernő approaching her on Jesenska utca, Anna came to a halt.

‘That bag had my passport and credit cards in it. Everything, perkele,’ she said, and noticed she was swearing in Finnish.

‘What about your phone?’ asked Ernő. He was so out of breath he could hardly speak. His cheeks were glowing red and his brow was covered in sweat. You should go for a run more often, Anna found herself thinking meanly.

She tapped her jacket pocket, discovered that her phone was still there and showed it to Ernő with a look of feigned victory on her face.

‘Hah, at least they didn’t get away with everything.’

‘Damn tinkers,’ said Ernő.

‘How do you know that?’ asked Anna, somewhat taken aback. She hadn’t seen anything of the thief but the back of his jacket.

‘Well, the girl looked … you know. It’s obvious.’

‘Looked what?’

‘You know … untidy.’

‘How closely did you get a look at her? I didn’t really see the man at all. Height, one hundred and eighty centimetres; average build; dark jacket; but if someone asked me to describe him, I don’t think I could do it. I guess he’s probably fairly young, thirty at the most.’

‘So you didn’t get a look at him then? I don’t think I’d be able to say anything at all about the girl either.’

‘Height? Age?’

‘She couldn’t be very old because she was quite small. Nothing but a kid. I didn’t really see.’

‘But you said she looked untidy. In what way?’

‘I can’t say really. It must have been her hair. Long and tangled.’

‘And that automatically makes them Romani, does it?’

Ernő couldn’t avoid the irritated tone in Anna’s voice.

‘Come on, you’d recognise them a mile off,’ he said, trying to defend himself.

‘The girl was wearing a red skirt,’ said Anna.

‘Was she?’

Anna hadn’t paid the thieves’ ethnic background any attention. And if Ernő hadn’t noticed the girl’s red skirt, how could he possibly have seen whether her hair was untidy? His observation was nothing but prejudiced supposition, thought Anna. Was there a single place on earth where ‘gypsy’ wasn’t a synonym for ‘thief’? She swallowed her desire to give Ernő a piece of her mind. After all, he might be right. To Anna the average Romani looked exactly like the average Serb or Hungarian. Over here the Romani women didn’t wear frilly blouses and black velvet skirts, and the man didn’t wear straight trousers and a jacket like they did in Finland, where they clearly stood out from the crowd. Here they dressed just like everybody else. But still, people here seemed to know just by looking who was a Romani and who wasn’t. As if having a skill like that was in any way important.

‘They live nearby, don’t they?’ asked Anna.

‘I don’t think they were locals.’

‘What makes you say that?’

‘This is such a small town, the locals have to go thieving elsewhere. Everybody knows everybody else. Almost.’

‘Shall we go and take a look?’

‘They won’t let us in, and we can hardly batter the door down. They’d shoot us first. And if those two have gone that way, they’ll be well and truly hidden by now. The most sensible thing is to go straight to the police station and report the theft.’

Anna thought about this for a moment. The idea of snooping round the gypsy quarter by night appealed to her, but still she hesitated. Maybe it really would be best to report the theft at the police station. What a great start to her relaxing holiday. Just then the sound of a dog barking could be heard in the distance. Ernő turned his head and listened closely.

‘That’s coming from the gypsy quarter,’ he said.

‘Right, we’re going down there.’

‘The hell we are, in the middle of the night.’

‘Are you afraid?’ asked Anna.

‘No.’

‘Neither am I, so let’s go.’

Anna wiped the sand and grit from her feet and put on her shoes. Her socks were torn to shreds and there was a bleeding cut on the ball of her left foot. She tried not to think about the searing pain that was now running up her calf muscle, or that her high heels weren’t making it any better.

The clack of Anna’s shoes echoed across the deserted street. She was irritated. She’d had to pick these shoes, hadn’t she? And tights and a skirt. It meant something, she thought. She was wearing more make-up, more feminine clothes than in Finland. What exactly was she trying to hide? Or reveal?

The dog had stopped barking. The silence was sultry and oppressive.

The town came to an abrupt end at a large brick factory. The edge of the town looked like it had been measured with a ruler. On the final street before the factory stood a white, roughcast, terraced house. The courtyard was on the side facing the factory; the building’s run-down façade was half the length of the street and completely concealed the view into the courtyard. The windows were all dark.

Anna went up to the locked gate.

‘Is there anyone there?’ she shouted. ‘Open the gate!’

Tethered to a thick chain, a mongrel that resembled a dachshund appeared from around the corner and growled.

Ernő stood further back, agitatedly glancing around.

‘They might have guns,’ he whispered.

‘Nonsense,’ Anna scoffed and rattled the gate. ‘Open up!’

The dog started barking, a window near the gate opened up, and a young-looking woman poked her head out.

‘Who is it?’ she asked.

Anna stepped closer and stood right beneath the window. The woman’s thick, black hair was tied in a bun. Her skin was dark, and she was very beautiful. Her eyes were large and pitch black. And as she looked down, Anna thought they betrayed a sense of caution. There was something else in her expression too. Maybe pride, maybe contempt.

‘What do you want? You’ll wake up the kids,’ the woman snapped.

‘We’re looking for a young man and a little girl in a red skirt. Have they just come into this house, by any chance?’ Anna asked.

‘Nobody comes in at this hour. We’re all asleep.’

‘Mummy, who’s there?’ came the sound of a sleepy child, a little boy perhaps.

‘Back to bed now, there’s nothing to worry about,’ the woman said gently before turning back to Anna. ‘Has something happened?’ she asked and looked Anna in the eyes.

Anna felt embarrassed. It was as though the woman could see right through her, as though she knew exactly what had happened and who they were looking for. There was also something very defensive about the woman’s demeanour, and Anna couldn’t tell whether this was aimed at her personally or the people she represented. She wasn’t welcome here; that much was clear. She no longer wanted to disturb the peace in their house.

‘We’re probably in the wrong place. Sorry to disturb you,’ said Anna, then turned and nodded to Ernő as if to say it would be best if they left.

They had only walked a few metres when the woman’s voice echoed across the stone walls of the houses.

‘Tiszavirág,’ the woman shouted in a voice that made Anna shudder. The flowering of the Tisza – when the river’s long-tailed mayflies all hatched and mated in the space of a few short days.

Anna and Ernő stopped and turned around, but the window had already closed behind them. The cut in Anna’s foot was throbbing painfully.

‘What on earth was that about?’ asked Anna.

‘I don’t know, but I know that woman.’

‘Really? Who is she?’

‘Her name’s Judit. She’s an organiser for the local Romani community group. She runs camps for the kids, that sort of stuff.’

‘But that sounds great,’ said Anna.

‘Well, they probably get money from the council for it,’ Ernő replied. ‘Let’s call Tibor. Maybe he caught the girl.’

Ernő took out his phone and exchanged a few quick words with Tibor. He shook his head at Anna. The girl had disappeared. Tibor and the others were going home for the night and didn’t feel like partying any more.

‘Let’s stop by the police station. It’s best to report the theft immediately rather than tomorrow,’ said Ernő after he’d finished his phone call. ‘What a crap start to your holiday. Never mind, we’ll make up for it.’

DZSENIFER CREPT BACK towards the town. Branches tore at her already tangled hair and her little feet were soaked from the muddy earth, where even the smallest depressions had captured water from the flooding Tisza. She had crouched by the riverbank until it was light, to make sure the monster had disappeared. She had gone down to the water’s edge to take a look at her brother. Then she’d picked up the passport and the credit card, which lay in the mud, and stuffed them in her pocket. She lifted her gaunt face to the sun and tried to forget everything that had happened that night. That’s what she’d done when Mother had died, and it had helped then too. But that was so long ago that Dzsenifer couldn’t really remember what she’d done or thought.

She walked towards the town centre and sat down near the bus station. She felt as though she blended into the group of people loitering around there, people whose skin and hair was as dark as hers. She didn’t know who they were, where they had come from or why. But she knew that her brother had had some dealings with them. Business, he’d always said. For Dzsenifer business meant bread and meat, milk and burek. When her brother’s business was doing well, she could eat until her tummy was full, and when business was slow they were hungry. That’s when she snuck round to the neighbours’ house. The tables next door weren’t exactly overflowing with treats either, but Dzsenifer didn’t expect them to be. The neighbours gave her bread and lard. When your stomach was howling with hunger that was a treat above all others.

This summer her brother had had plenty of business, and Dzsenifer couldn’t remember the last time she’d gone hungry. Now she felt a pinch at the bottom of her stomach. She started to cry as the image of her brother lying by the banks of the Tisza forced itself into her mind. Perhaps her brother would wake up and find her later. Maybe he’d just been sleeping more soundly than usual. Maybe the horrible man who’d attacked him had only appeared in Dzsenifer’s nightmares. She often had nightmares. That’s why she was afraid of going to sleep. That’s what must have happened.

Her brother would come home later.

Dzsenifer knew what to do with the passport and the credit card. She knew where to take them. All those people who had wandered here from places she didn’t know and who spoke strange languages and who seemed to fill every bit of the town, they were in the same place she was going. One of them would buy the passport. Then Dzsenifer would be able to buy lots of bread.

The bus jolted to the stop, its exhaust sputtering. The driver stepped out to smoke a cigarette, looked at the crowd of people and shook his head. Dzsenifer felt like darting into the bus, but she waited until the driver had smoked his cigarette, thrown it to the ground and stamped it beneath his shoe. Then she stepped calmly up to the driver’s booth, bought a ticket and went to sit on the back seat. Neither Dzsenifer nor anyone else paid any attention to the grey-haired man sitting in a car parked in front of the Venezia pizzeria and watching her leave.

JUNE 4th

A CLATTER COULD BE HEARD from the kitchen. Anna opened her eyes a fraction. The blinds in the upstairs room were pulled so tight, the light only came through in tiny bright spots, like pinpricks in a black window. As her eyes grew accustomed to the darkness, she began to make out the contours of the familiar furniture: the desk beneath the window, the small bookcase in the corner and the armchair with her clothes thrown over the back.

Once Anna had turned eighteen, her mother had returned to their former homeland. This used to be Anna’s room as a girl. The toys had long since been packed away and taken up to the attic, or given to relatives with young children. There were no posters or photographs on the walls, because that phase of Anna’s life had only begun once they arrived in Finland. It hadn’t really taken off there, though; unlike all the other teenage girls at school, Anna had never been head over heels about any particular band or actor. She’d taped a few posters to the wall of her room in Koivuharju, but only so that she didn’t seem like a total freak if one of her classmates visited. She couldn’t even remember which bands they were. She did remember that guests at their house were few and far between.

‘Kértek a pálinkát?’ Anna could hear the creak of the pantry door, the sounds of her mother fussing round the kitchen. Anna looked at her phone. Ten o’clock. That meant it was actually nine o’clock, because her phone hadn’t automatically changed to local time. Pálinka at nine in the morning – home-brewed fruit liquor that was stronger than vodka, thought Anna, and smiled. Welcome home.

She changed the time settings on her phone and listened to the agitated chatter from downstairs. She truly didn’t want to get out of bed yet. It must have something to do with yesterday’s handbag theft, she thought as she gently stroked her stomach. She made out the words ‘gypsy’ and ‘thief ’. Maybe they’d caught up with the culprit. Maybe she wouldn’t have to get up just yet, have a shower, call Ernő and Tibor, go back to the police station and try to establish a chain of events while her friends interpreted. Most of the local police officers were Serbs and Anna’s grasp of the language wasn’t up to scratch. Some of those who had worked in Kanizsa for years spoke Hungarian too, but the young duty officer who had been there the night before had been so monolingual that Anna suspected he might have been from Kosovo. It was ironic that here, in her so-called homeland, she had to rely on her friends’ interpreting skills to deal with the police. The duty officer had sat smoking in his Plexiglas booth, logged the event in his computer and encouraged them to come back in the morning when there would be more staff around.

No police stations on holiday, thank you. No interviews, eye witnesses, uniforms, investigations – Anna didn’t want to remember that such things even existed. She wanted to lie in, drink Turkish coffee with her breakfast, let her mother make a pleasant fuss and wait on her. She wanted to buy warm white bread from the local bakery run by the Albanians, walk along the banks of the Tisza with Réka, talking about everything, sweat in the heat, and eat cherries straight from the tree. She would have time to do all those things before the holiday was over: if the weather remained this warm, the first cherries would ripen at the end of June. But of all the bags to steal, someone had stolen hers. Could she have had any worse luck? Anna thought, rubbing her eyes and stretching her arms.

Réka hadn’t joined them last night. They had messaged back and forth throughout the day and Réka had said she’d been working in Szabadka, the nearest large city on the Serbian side, which in Serbian was called Subotica. Eventually Réka had said she’d felt so ill all day that she didn’t want to drive all the way to Kanizsa. Anna was disappointed because Réka normally joined her as soon as she arrived. Feeling ill sounded like an excuse. Réka has something going on, something more important than me, Anna thought, almost jealous. But her other friends had been waiting for her at the house, and she’d hardly had time to eat or exchange news with her mother before they rushed her off into town. Then her handbag had been stolen and she’d forgotten all about Réka.

Anna reluctantly swung her legs out of bed and placed her feet on the brown, patterned carpet, the kind that were popular when the house was built in the seventies. It’s so handy not to have to take rugs out and air them, her mother used to say. Nobody thought then of the dust and dirt that became ingrained in them over the years – she wasn’t sure they thought of it nowadays either. In a country where people still smoked indoors, the dirt clinging to fitted carpets wasn’t a particular concern. Anna went into the bathroom and noticed that the voices in the kitchen had fallen silent. An unpleasant sensation pressed down sharply on her chest, the same way a mother feels when she realises the sound of her child playing has stopped: something has happened.

Anna quickly pulled on her clothes, didn’t bother brushing her teeth or combing her hair, and went downstairs.

A man and two women were sitting in the kitchen. As Anna appeared in the doorway, they turned to look at her but didn’t smile or greet her in the normal, cheery fashion.

‘Your bag has been found,’ said her mother.

Anna was puzzled at the subdued atmosphere.

‘That’s great, isn’t it? Let’s drink to that,’ she said. She walked over to the kitchen cabinet, took out a glass, ran water from the tap in a hopeless attempt to cool it, then took a long gulp of lukewarm water and looked at the assembled group of people, none of whom raised their glasses of fruit liquor to their lips.

‘This is Kovács Gábor, his wife and their neighbour, Gulyás Katalin,’ said her mother. ‘You’ve met them before. Gábor was a policeman at the same time as your father, though he’s been retired for a while. How long is it now, Gábor?’

‘Seven years since I left the force,’ the man replied in a low, pleasant voice. The hair across his brow was grey and silvered, he wore a thick moustache, and his eyes were brown and alert.

‘Is it so long?’ said her mother, almost to herself, and shook her head.

‘Where did they find my bag?’ asked Anna.

Only once she’d spoken did she realise that she hadn’t rolled out the usual formal greetings and pleasantries. One of the women, the policeman’s wife, seemed to turn her nose up. She probably thought Anna was an impolite brat. Anna had felt this same awkwardness countless times before, particularly around older women – the barely hidden rejection that began to seep from them like frost from an opened freezer the minute Anna forgot to use the right words in just the right way. She would never be a hölgy, never be considered an úriasszony, a lady, a woman who understood the rules of etiquette, her family life in impeccable shape and her cupboards in order. This fact she had to face every time she met her mother and her mother’s friends.

‘Some way along the banks of the river, down towards Törökkanizsa,’ said Kovács Gábor.

‘Was my wallet still there?’

‘Yes. But we’ll have to establish whether anything’s been taken from it. Do you have a credit card?’

‘Yes, a Visa card.’

‘Well, that wasn’t there.’

‘I cancelled it last night, so it’ll be no use to anyone.’

‘Good. Did you have much cash with you?’

‘A few thousand dinars. I only arrived yesterday, so I hadn’t had time to change any more.’

‘There were only a few coins in your wallet. The notes had been taken.’

‘Of course. What about my passport?’

‘Gone, I’m afraid.’

‘Brilliant,’ Anna said, disappointed. The loss of her passport meant she’d have to contact the embassy in Belgrade and fill out who knows how much paperwork. Fucking hell, she cursed to herself.

‘Isn’t it just bushes down that way?’ she asked. ‘Do you know how the bag ended up there? Did you catch the thief?’

‘We’ve got the thief,’ said Kovács Gábor.

‘Who is he?’

Her mother cast a worried look at the elderly policeman, and he nodded at her almost imperceptibly.

‘Was he…’ her mother said quietly. ‘He was lying next to your bag. Dead.’

‘What?’ Anna gasped.

‘We don’t know who he was,’ Gábor explained. ‘But he wasn’t from round here. He’d drowned. It appears he stumbled into the water and got himself caught on some tree roots spreading out into the river; they stopped him from being washed away with the current. Your bag was on the shore right next to him.’

‘Úr Isten!’

‘The man might have gone into the bushes to clean out the bag and slipped into the river – the ground round there is muddy and slippery, and the bank is quite steep. Naturally, the police will conduct a thorough investigation. You’ll have to come down to the station as soon as you can and tell us everything that happened last night. We’d like to speak to your friends too. The police will need witness statements from everyone who was present at the time of the theft; even the smallest detail might be of use in the investigation.’

‘I know,’ said Anna and looked out of the window. The morning sun shone enticingly, promising another scorching day. ‘I’m a criminal investigator too, in the Violent Crimes Unit.’

‘Your mother told us. As you see, I still help out at the department. I can’t seem to keep away.’

‘Were you there when they found the thief?’

‘No. I leave crawling around in the undergrowth to the younger ones. But I went to the station as soon as I heard the news. And we all agreed it’s a good idea to have a Hungarian officer helping you sort this out. Our younger colleagues are almost all Serbs.’

Helping me: Anna repeated Gábor’s words to herself. Sounds as if I’ll have to spend my holiday assisting the police. Great.

‘That’s kind,’ she said out loud.

‘I’m sure we don’t have the same kind of resources as the Finnish police, but you can be sure we do our job as well as we can. I imagine you’ll be fascinated to see how we work round here. You’re your father’s daughter,’ said Gábor.

‘You look just like him,’ the policeman’s wife added and attempted a smile.

I guess I do, and I suppose I am, thought Anna. And my holiday is ruined.

‘Voi vittu perkele,’ she swore in Finnish and smiled.

‘What does that mean?’ Gábor’s wife asked, suddenly curious. Anna’s mother shot her a look that was sharper than a dagger.

‘“How interesting”,’ Anna replied and headed for the shower.

THE POLICE STATION in Magyarkanizsa looked like a desolate apartment block. The giant yellow box was situated on a quiet side street on the edge of the town centre, right next to the tangled woodland that continued all the way to the riverside. Somewhere down there Anna’s handbag and the dead thief had been found.

Anna waited for Ernő and Tibor in front of the station. In the small courtyard was a statue in memory of local policemen who had died during the Yugoslav war – a little monument engraved with officers’ names. A painful memory momentarily punched the air from Anna’s lungs, and tears welled in her eyes. Her eldest brother, Áron, hadn’t been a policeman. He hadn’t had the chance to be anything other than a wild young man, whose studies, and eventually his whole life, were cut short by the war. Ákos still carried inside him the pain of losing his older brother; they’d been very close, almost the same age, and always together. Anna swallowed her tears. It was hard to bring Áron fully to mind, Anna’s memory of him had faded so much. His face, his body – now they were familiar only from photographs. Anna could no longer truly remember his voice, the way he walked, his gestures or expressions. And yet the pain of losing him was like a heavy weight hanging from her shoulders. What must it feel like for Mum? she wondered. Her mother never spoke of Áron. Or of her father.

‘Szia!’

Anna heard the cheery greeting from across the street and looked up from the monument, where someone had lain a wreath woven from red flowers. She waved to Ernő and Tibor. Ernő looked the worse for wear.

‘Sziasztok!’

They walked inside the station and explained who they were to the young officer on duty, who, to Anna’s surprise, was a Hungarian. And quite good-looking. The man asked them to sit down on the brown, metal-legged chairs and wait for the detective.

‘It seems there are Hungarians working here after all,’ Anna said to Ernő and nodded towards the man sitting in the booth at the entrance. The man looked back at her, not even trying to hide his interest. Anna could feel the blood rushing to her cheeks and she quickly looked away again.

‘Sure, there are a few. Why wouldn’t there be?’

‘I was told most of the police officers were Serbs nowadays.’

‘Well, they’re in the majority, like they are in the border patrol. But as far as I know there has to be a quota of Hungarians, so some of them must be our lot. The nearest Hungarian-speaking high school is in Törökkanizsa, although that’s mostly a Serbian-speaking town.’

‘What’s that got to do with it?’ asked Anna.

‘Think about it, you’re a smart woman,’ Ernő scoffed and didn’t look like he was going to explain any further.

‘Just tell me.’

‘The government is using deliberate political decisions like that to drive our language and culture into the ground. They’re just trying to make our lives difficult. Sure, it looks great that there’s a Hungarian-speaking high school, but why isn’t it here in Kanizsa? Why did they have to locate it in a neighbouring town where there aren’t many Hungarians?’

Ernő’s tirade was interrupted by the arrival of a tall, authoritative-looking, grey-haired man in a uniform laden with medals. The chief of police himself had come to meet her. Anna was rather taken aback. The man introduced himself and apologised in awkward Hungarian that he wouldn’t be able to deal with the case in Anna’s native language. His former colleague, Kovács Gábor, had kindly agreed to assist them. Anna nodded. I know, she answered in Serbian. She knew a few words and phrases, thanks to Ákos’s old friends – Zoran in particular.

The chief of police led them to his office on the second floor, where Gábor was waiting for them. The chief picked up the phone on his desk, made a call, and a moment later there came a knock at the door and an officer in uniform brought in Anna’s handbag. The officer was wearing gloves and the handbag had been placed in a transparent plastic bag.

‘Could you inspect it to see what is missing,’ said Gábor.