Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Seren

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

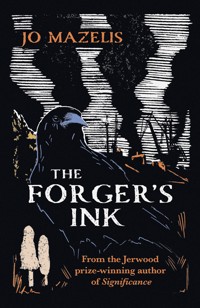

It's the 1970s, and a mysterious woman has a cache of letters which claim to tell the story of the death of Fanny Imlay, half-sister of Mary Shelley and daughter of Mary Wollstonecraft. Did Fanny really commit suicide in an inn in Swansea in 1816, as historians thought? The letters instead suggest a faked death and an escape from Fanny's fraught family life. It could have been an independence of which Fanny's mother would have been proud. But the letters also suggest the re-born Fanny remained misunderstood, mis-used and rejected, in the manner of Mary Shelley's Frankenstein's monster. The women's intertwining narratives begin to reflect each other as the mysteries multiply and resolve. Gothic body-swaps, dark mansions and unexpected deaths merge with 70s politics and feminism in this tour-de-force by Jerwood Prize-winning author Jo Mazelis. "The Wollstonecraft-Shelley story is a founding myth in Gothic literature; Jo Mazelis tears it to shreds and reassembles it, amid the thick sea mists of south Wales, with Cymbeline and the Manson girls among her dramatic sources." – Geoff Sawers, author of Widdershins Walk

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 423

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Also by Jo Mazelis

Diving Girls

Circle Games

Significance

Ritual, 1969

Blister & Other Stories

Photography

The Democratic Elvis

Seren is the book imprint of

Poetry Wales Press Ltd

Suite 6, 4 Derwen Road, Bridgend,

Wales, CF31 1LH

www.serenbooks.com

Follow us on social media @SerenBooks

© Jo Mazelis 2025.

The right of Jo Mazelis to be identified asthe author of this work has been asserted in accordancewith the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988.

ISBN: 978-1-78172-432-3

Ebook: 978-1-78172-433-0

A CIP record for this title is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced,stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted at any time or by any means,electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise withoutthe prior permission of the copyright holder.

The publisher acknowledges the financial assistance of theBooks Council of Wales.

EU GPSR Authorised Representative

Logos Europe, 9 rue Nicolas Poussin, 17000,

La Rochelle, France

E-mail: [email protected]

Printed by CMP UK Ltd.

Map and illustrations © Jo Mazelis 2025.

Cover design: Jamie Hill 2025.

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organisations,and events portrayed in this novel are either products of theauthor’s imagination or are used fictitiously.

To Swansea and all who sail in her;

past, present and future.

PART ONE

1967-1971

‘Now more than ever seems it rich to die,

To cease upon the midnight with no pain.’

From ‘Ode to a Nightingale’ by John Keats

FERRYMAN’S COTTAGE

1968

Judith Hopkins did not believe in ghosts.

Her life had been too full of real monsters to consider other, unseen forces. Her mother was long gone and she’d finally left her father to whatever demons possessed him – most, she was certain, came from the bottle, but as she had never known him sober how could she tell?

She changed her name, shortening it to Jude and that was a rebirth, a liberation.

She became Jude from the Beatles’ song. Never Judy as in Punch and Judy the powerless object of unbridled rage.

As names went, Jude was best.

Hey Jude.

She had inherited a house. A ramshackle place with a jerry-built, glassed-in extension and a wild garden that ran down to the river. Her mother’s father was born there and lived there until he and the house were both crippled nearly beyond redemption. Grandpa Powell had left his home and died at the hospital two days after being admitted. She never really knew him; had only a vague memory of a visit and someone (it must have been her mother) loudly weeping.

After leaving the solicitor’s office on Walter Road, she’d walked through the grounds of the church opposite and into St James’ Park where it was leafy and cool. She sat on a freshly painted wooden bench and stared at everything around her, unable to grasp what had just happened. The key to the house grew so warm in her hand that she could no longer feel it. She had to look to see if it was real.

She moved into Ferryman’s Cottage the next day, certain her father would drag her back, certain a mistake had been made and the house was not hers. She remained as nervous as a rabbit in a hutch, only secure when nothing came to disturb her, but skittish whenever anyone, friend or foe came near.

She took to silence. A profound silence that grew deep inside the thick walls of the old cottage. She liked to imagine herself in another century. She made her little journeys into the modern world only to buy the necessities of life, the small loaves of bread, the tins of salmon and soup, the tiny jars of bloater paste, the jolly packets of Typhoo tea. Her clothes came from jumble sales.

On her sallies into world, she sat on benches wherever she found them, in parks and on the promenade or outside the old hospital, and from those places, with a book held open on her lap, she surveyed all she saw and began to notice how codes of dress marked people out. Particularly young people. Young men’s hair grew longer, women’s skirts got shorter and shorter, then just as abruptly dropped to floor length.

Women over a certain age still had their hair cut short and wore it permed in a crown of black or brown or yellow-blonde. Then when they were older their hair turned an honest grey, or naked white, or was rinsed in shades of blue, mauve or palest pink. Spectacles were either clunky black or tortoiseshell, or they grew wings. Children’s National Health glasses were round and surgical pink or blue depending if for a boy or girl. Schoolboys wore shorts to school until they were fairly bristling with testosterone and stubble, while girls’ growing bosoms were imprisoned in old-fashioned gymslips and shapeless blazers. Nurses wore navy wool capes with a scarlet lining, the bus conductor his cap. Nuns sailed by in clouds of black.

If anyone caught her eye or tried to speak to her, Jude lowered her head and read furiously, until they gave up and went away.

The old house, the ferryman’s cottage, had been built in the seventeenth century and all its ghosts, or so she’d heard, were the drowned dead and they came squelching and dripping, fish-nibbled and green with slimy weeds out of the river. At night, strange sounds like lapping water or the cries of animals terrified her, but by daybreak these noises were once again made mute or banal. The water noise was just traffic on the nearby road or it was wind in the trees; what had sounded like the jangle and creak of oars was the milkman rattling his crates, the screams were seagulls calling. That was all.

The unearthly chill, the creeping damp, all had their rational sources, Jude told herself, but she felt helpless and did nothing to remedy them. One awful winter, a bout of flu turned into a chest infection and she lay for nearly a fortnight in her damp bed with her lungs clogged and rattling, certain she would die there alone. When, finally, a little of her strength returned, she went out. She was like a walking corpse, gasping for air, weak as a newborn kitten. One step, another step, another. She had to get to the shop, had to get bread and milk. Get sausages, get a slab of greasy cheese. A banana that she could eat immediately.

Her eyes were sunk in her face and the black shadows beneath them gave her the aspect of a prisoner in a concentration camp. Her hair was a mass of knots and tangles. Not that she’d looked in the mirror. She was still running a temperature, still half-mad with a fever.

On towards the shops she trudged. Outside the greengrocer’s two prams were parked, a baby inside each. The sun was out, the sky blue with huge white clouds hanging in them. She drew level with the first of the prams, all black canvas and silvery suspension parts, with the hood turned up to protect its tiny passenger from the sun. Jude had been feeling giddy all the way, but moved forward, letting the momentum carry her. She stopped a moment to catch her breath before she entered the shop.

Once inside, while the assistant glared at her, she manged to say ‘banana’, then ‘please.’ No good, not saying please, even if she was dying. A whole bunch of bananas were placed on the scale and her request for just one was, after a moment’s hesitation, disdainfully obeyed. The room was kaleidescoping around her and grew black at the edges. She paid and lurched out of the shop, misjudged the depth of the doorstep, reeled unsteadily. She was a sailor setting foot on dry land after months at sea. She was a girl again, stepping out of the carriage on the waltzers at the funfair after she’d been spun around and around, with the flashing lights above her and the pounding music blaring, her legs all gone to jelly. To stop herself from falling, she grabbed at the nearest solid thing, which was the black pram. No sooner had she touched it than a cry went up from inside the shop and Jude, letting go as if stung, fell to the ground, leaving the pram lurching and rocking above her on its springs.

When they realised she wasn’t a baby-snatcher and neither drunk nor drugged, an ambulance was called. She was taken to hospital, where after nearly three weeks of sleep, food and antibiotics, she recovered.

‘Forty years ago, you’d have been a goner!’ the porter cheerfully told her. He was young and in between his other duties he made it his business to talk to everyone. ‘If it wasn’t for the miracle of penicillin, you’d be kaput, pushing up the daisies, six feet under, toast! You poor dab.’

‘Shut up Eddie,’ said a nurse. ‘We don’t talk about that, do we?’

‘Nah, better not, eh? Touch wood.’ He tapped his head. ‘Back home today then, Miss. But don’t forget, a ’undred years ago you’d be the dearly departed.’

Back at the cottage she took account of her life. It was true – she might have died of pneumonia. Or simply starved to death, if she hadn’t found the strength to go out. A hundred years ago, two hundred years ago, nothing could have saved her. And what had she done with her life? Nothing, came the dire answer.

She remembered the sensation of her choked lungs as they filled with fluid. It must be like drowning, she thought. Like those ghosts who drifted up from the river at twilight. Her lungs opened for air and found only liquid. Her fever sent her wild, vivid dreams and these seemed to cling to her still. They came back in brief moments, very alive and nearly tangible.

She wanted to remember this. To remember how close she’d come to dying. She also wanted to be remembered. To not die alone with nothing to show for her miserable life. The only way of doing this was to leave a record. She would write everything down, but write it as if it had all been a hundred years ago. One hundred and fifty years ago.

THE STORYTELLER

She began one evening with a blue biro and a cheap reporter’s notepad. The pen produced nasty gobbets of ink that, if touched, smeared. It made what she wrote ugly and the pen dried up gradually too, so that parts of what she wrote grew fainter and fainter until there were only the traces of indentation from the tip. She searched the house and the first pen she found had green ink. She used that, then when that ran out, a red pen and finally a pencil. Five hours produced twenty pages of such utter ugliness that she almost wept. The next day, in despair and on the brink of throwing the pages away, she reread her words. It was hard to ignore the handwriting, the blue, green and red ink, the blurry pencil marks, the narrow blue lines on the paper, the smudges, but somehow rising from the ruins like a phoenix, she saw that her words had power.

Somehow in the scratch and scribble, the niggling frustration with the various pens (which was all she really remembered of the day before) something had emerged which, as words are wont to do, spoke to her. But the most remarkable thing was that she had the sense, the very strong sense, that the sentences, the ideas, the syntax belonged to a presence other than herself.

Yes, she had been the one scribbling the words. Yet it had been, she thought, with a mingled sensation of fear and joy, as if she had been taking dictation from another wiser being. A being who did not belong in the twentieth century with its oil spills, its transistor radios, its rumbling articulated trucks, its factories, its plastic everything, its pollution and nuclear reactors and atomic bombs. It was a voice from a purer age, nearly but not quite entirely innocent.

Jude looked up from the page, her gaze travelling over the room as if the author of these words might step forward at any moment and introduce herself. This author, or rather ‘authoress’, for Jude was in no doubt that the voice was a woman’s, seemed, as all ghosts are said to be, an unhappy, restless spirit with unfinished business to settle.

Jude picked up the pencil and, turning to a fresh page, sat waiting for more words to come. She listened, straining at the silence in the room and inside her head. For half the morning it seemed, she sat with the pencil poised over the paper. She tried closing her eyes. Nothing. She opened them, sharpened the pencil and again waited. But still, the voice or the dream or whatever it was, evaded her.

What had happened yesterday? she wondered. What was different? It had been later in the day; by the time she had begun to write the sun was already low in the sky. As she’d worked, the light had faded until the paper seemed to turn grey, and even the red ink was drained of its colour. Then, when she’d got up to switch on the overhead light, the bulb had popped and so, lacking a replacement, she’d lit the candles in the old cast iron candelabra and set it on the table, where its warm yellow glow cast flickering shadows.

It was easy to imagine that something, some ancient unseen entity, had caused the electric light bulb to fail, forcing Jude to write by the source of illumination it was familiar with. Or was it simply a matter of atmosphere? The candlelight of romance and witchcraft and psychics and séances. Easy to think that something malevolent or otherwise had crept into the house and wrapped its wraith-like form around her in order to guide her hand. She almost saw it in her imagination, a vague form like a mist that, when she inhaled, was drawn like a trail of thin smoke into her nose and her mouth, and from there circulated to every part of her body, to her lungs, bloodstream, heart and brain.

She remembered all too well the difficulty with the pens and the light bulb, yet her thoughts as she wrote, her plan or ideas or inspiration, were now a blank. It was as if she had been in a trance.

She was still feverish, her head when she touched it with the back of her hand felt hot, but the exhaustion had passed. It was eleven o’clock, the day ahead seemed to wait for her, the sun was out and there was no wind. She would walk to town and besides the necessity of some money from the Post Office and some food, she determined to go to the reference library on Alexandra Road and see if she could discover anything about hauntings and possession.

Before that day, she had never dared to enter the reference library; now she stepped into the huge circular room and was awestruck by it. The central well was filled with long tables at which various scholars sat amid piles of books, some merely reading, others busy making notes. None looked up, or if they did it was only the nearblind momentary glance of someone whose mind was elsewhere. The curving walls were dense with shelves of books, and an upper level was reached by an ornate metal balcony. High above was a great domed ceiling that let in some light, though evidently not enough, as there was also electric lighting.

To her left was an information desk with a small office behind it. Noticing Jude, who had stepped only a few paces into the library, a man behind the thickly varnished wooden counter asked, in a voice that was not quite a whisper, ‘Can I help you?’

She hesitated. Her impulse was to turn on her heels and run, but something, some new strength or trust in strangers, perhaps due to her recent hospital stay, or maybe it was this other being who had possessed her, made her say with unruffled confidence, ‘Yes, I want to see any books you have on the supernatural.’

‘Did you want something on local paranormal sightings?’

‘Maybe.’

‘I have a file here for just that – newspaper clippings, photostats, some handwritten notes. The haunted rectory at Rhossili, the ghost of Swansea Castle, the white lady of Oystermouth: suicide, sorrow, suspicion, all the usual palaver.’

He sat her at a table near the desk and brought her a manila folder filled with a jumble of papers. She had been unprepared for this, bringing neither a pen or paper to make notes. So, uncertain what she was doing, she looked through the material, glancing over the news story about the ‘melancholy discovery’ of an unknown woman and an apparent suicide note. In the margin someone had written ‘is the reported ghost in Wind Street?’ Jude’s interest was wavering and self-conscious. She was reading while also pretending to read, aware of the other people in the room whom she assumed to be ‘real’ scholars, not scarecrow students like her.

Later, she bought her other bits and pieces – bacon from the market, a meat pie and a small Hovis from Eynon’s, a new fountain pen and a bottle of Quink ink from WH Smith’s as well as unlined writing paper. Walking through town, she caught sight of herself in shop windows. Her face had the appearance of a skull, gaunt with dark eyeless sockets, bone-white skin. No wonder the man in the library had stared at her.

Her appetite had, at last, come back. She went into Woolworth’s on the High Street and headed upstairs to its vast cafeteria. She ordered sausage, egg and chips along with two pieces of bread and butter. The chips were pale and soggy but she ate ravenously without a hint of the self-consciousness that usually plagued her. She washed it all down with a good strong cup of tea in a white Pyrex cup.

Before leaving the shop, she bought a pack of household candles and some light bulbs. Her mind, or so it seemed, was already entering the trance-like state she remembered from the day before. The fact that it was probably just tiredness and the dwindling effects of her illness or the natural effects of eating a greasy, stodgy meal did not occur to her. She hurried for the bus, stared blankly at the cheery bus conductor when he tried to chat about the weather, her eyes going out of focus, then tearing up with weariness. She was shaky by the time she’d reached the cottage, her hands visibly trembling. After drawing the curtains, she lit the candle and filled the new pen with ink. Its weight was sacrosanct. She sensed it in the palm of her hand for a moment, then forgot about it as she began to scratch out a story.

The threads of her tale seemed to arise unbidden; she began to frighten herself as the story spooled out. Everything frightened her, although she’d never have admitted it. She was a coiled spring ready to run at the merest hint of danger.

She gathered up the pages, lit the gas ring, and one by one burned them, dropping them into the white enamel sink where they turned into brittle black flakes.

PART TWO

1967-1971

‘Then up I rose,

And dragged to earth both branch and bough, with crash

And merciless ravage: and the shady nook

Of hazels, and the green and mossy bower,

Deformed and sullied, patiently gave up

Their quiet being’

From ‘Nutting’ by William Wordsworth

THE MUSHROOM GATHERER

Of course, people watched her.

They stood behind their privet hedges, their net curtains, their shop counters, and followed her with their eyes. Jude gave the impression of being oblivious, but she felt like Moses parting the Red Sea, a tide of turning heads following in her wake.

Today, with a red plastic shopping basket, Jude ducked into a copse of trees in search of shaggy inkcaps. The secret with these was to cook them within an hour or so of picking them. She planned to fry them in bacon fat along with a bit of stale bread. There was a piece of rough ground, a very secret place close to an abandoned industrial site, where they always grew. Once the mushrooms were gathered, the route back would provide handfuls of ramsons that she would throw into the sizzling pan near the end of cooking.

Anticipating the feast to come, Jude strode forward until a noise up ahead stopped her. Voices and a crashing, thrashing sound. Laughter. The hoarse, rogue voices of boys on the brink of manhood. Their talk so peppered with foul language there was hardly any normal word or meaning left. It was a school day, too. If they were as young as she suspected, they must be mitching. And if they were mitching off school, they’d be bored; bored to the point of trouble and until that trouble found you, you never knew the measure of it. The boys wouldn’t know either. Not until it was too late and there was blood on their hands.

Jude turned, going stealthily at first, then faster, and went back the way she had come. Nothing, not even wild mushrooms, was worth entanglement with feral boys. She decided to make her apparent retreat into a planned and necessary trip of exploration. She made her way to the abandoned grounds of a big house; there was a silted-over pond, the broken-down walls of ruined cottages, fruit trees, greenhouses without a bit of intact glass remaining, stables and the remains of an arboretum. The stately home had long been razed to the ground, its carriageways and paths swallowed up by alien species that Victorian collectors of rhododendron, bamboo and Himalayan Balsam had planted.

After hours of fruitless wandering, alongside a meadow and a shallow stream, she found what she was looking for. The inkcaps were standing in the undergrowth like a meeting of be-wigged lawyers with white and ruffled heads. Some had passed their best; others, with their skirts not yet flaring open, were perfect. Yet she hesitated before cutting them. How long before they melted away to black slush? How long would it take her to get home? While she pondered this, she failed to notice the approach of an old man.

‘They aren’t poisonous, you know,’ he informed her, barely breaking his stride.

‘I know,’ she called after him, her tone indignant. If he heard her, he showed no sign, but carried on along the side of the stream and went out of sight. Stubbornly, as if to prove a point, she cut five of the mushrooms low down on their stems and laid them in two rows in her basket like corpses. She carried on, following the remains of a lane. The route opened into the broad expanse of an overgrown meadow and at the furthest edge was an ancient oak tree with some stout branches low enough to climb. She quickened her pace in the direction of the tree, set her basket down and climbed easily onto the first low branch; she was looking for her next footing when she realised she was not alone.

It was the agitation of the furthest branches that alerted her; a rustling and a less than bird-like tugging. She followed the sound with her eyes and spotted a pair of sturdy boots and grey flannel trousers tucked into thick green knee-high socks. She got a glimpse of an arm, and hands reaching, pulling, picking something. Acorns? Bobbing about, she saw the person’s head: snow-white hair, deeply-lined skin, eyebrows gone mad as well as grey. Certainly, if he was the same old codger as before (and alone) he was no threat, so feeling piratical she jumped down from her perch and landed awkwardly.

‘Good gracious!’ the old man said, mildly. ‘You really should have shouted “timber!” or something.’

‘Sorry,’ Jude said, ‘I didn’t see you.’

‘Oh, I think you did.’

He managed to say this both knowingly and with enough warmth to make Jude blush. He had an accent, she noticed – a rising and falling in the pattern of his words.

‘Okay. Well, sorry again,’ she said.

‘Apology accepted.’

‘What are you doing?’ she asked. ‘Are those nuts?’

‘I could ask the same in reference to the contents of your basket.’

‘Mushrooms, that’s all. There’s no law against it.’

‘Are you sure? They used to hang boys for scrumping apples.’

‘No, they didn’t.’

‘Is that so? What are you going to do with them, make ink?’

‘No, I’m going to eat them.’

‘Before they deliquesce, I suppose. But you could make ink with them; did you know that?’

Jude was silent. She knew they were called Ink Caps but hadn’t imagined they could be turned into ink. She didn’t have a clue what deliquesce meant, but she wouldn’t ask; he’d only laugh at her. She guessed it was a word for how the mushrooms turned to mush.

‘Sort of,’ she said. ‘Anyway, what are those you’ve collected? Do you cook them?’

‘These?’ he said, holding out what looked like a handful of dull brown marbles. ‘Take one.’

She did as she was told; the nut, or whatever it was, turned out to be far lighter than she expected.

‘See that tiny pinprick?’

‘Yes.’

‘One would imagine something bored its way inside, wouldn’t one.’

Jude was tempted to reply sarcastically with, ‘One would.’ Or call him a poncey old twat. But she liked him, so, by way of reply, she merely nodded.

‘What happens is rather more interesting. An insect called an Oak Marble Gall Wasp, or Andricus kollari to give it its scientific name, grows from a larva and that is what creates these galls. The tiny hole is where the wasp emerged. When I say ‘wasp’, please don’t imagine those pesky yellow-and-black creatures that sometimes make a nuisance of themselves and give a nasty sting.’ He paused to study her face, ‘You must tell me if I’m delaying you. My wife tells me I talk too much.’

‘Oh.’ Jude didn’t quite know how to respond to that.

‘And speaking of my wife,’ he glanced at his wristwatch, ‘she’ll have my guts for garters. She’s waiting for me in the car and I said I’d only be half an hour. Must dash.’

‘But…’ Jude said.

‘Walk with me and I’ll explain the science and uses of galls.’

What could possibly go wrong, Jude wondered, and fell into step alongside him.

THE PROFESSOR

‘Now the gall, you see, is caused by the wasp, but made by the tree. It’s like a pearl in a shell – the organism gets a growth from an irritant; with the oyster it’s a grain of sand. Oh, look, a heron! Don’t they look ungainly flying? Where was I?’

‘Galls,’ Jude said.

‘Oh, yes. Now my wife will tell you that not only do I talk too much, I’m inclined to go off at a tangent. Galls, and these particular ones,’ he said, tapping the pocket of his tweed jacket which was bulging with them, ‘are excellent for making ink.’

‘Really?’

‘Yes, so naturally when I saw you gathering the Shaggy Ink Caps, that was my first thought. I looked at you and thought, art student, she’ll be making pigments. But then again more likely a gourmand. Certainly someone who walks unblinkered, who is unafraid of wild food. Was I right?’

‘I suppose so, but how do you make ink from those things?’

‘Well, it’s fairly simple. You need some large flasks and ferrous sulphate, and gum arabic. And water. And oak galls. I used to do it in the university’s laboratory, but now I use the garden shed. The smell, you see, is slightly unpleasant.’

‘Oh.’

‘But the odour is nothing compared to that of the Durian fruit, which I had the dubious honour of trying when I was stationed in Burma during the war. Not that Durian was the worst thing about that time and place. There was of course, the Death Railway.’

To Jude that sounded like a fairground ride; the ghost train, the wall of death, the death railway. ‘So the ink,’ she said, attempting to rein in his tangent. ‘Do you write with it?’

‘The ink? Oh, yes. Write with it, paint with it, draw with it. Just as with any other ink. Now in the eighteenth, nineteenth centuries, for someone who was literate and wanted to write a letter, the ink was no problem, very easily made, as were quills made from feathers. No, the expensive bit was the paper. People were economical with that.’

As they came to a particularly overgrown part of the old path, where shrubs with pretty pink flowers loomed ten feet high on either side of them, he said, ‘Ah, Himalayan Balsam, it’s an invasive species but…’

Jude was forced to fall into step behind him, so while he continued to talk, it was impossible to hear what he said. By the time the path opened up again, he was on another topic entirely. She didn’t feel she could interrupt, so he talked on, oblivious.

‘… the industrialists, for all their money and power, couldn’t escape the stench of the copper smelting, particularly on the east side of the river Tawe, so they abandoned their great houses and moved west. Ah, here we are!’

They had popped, almost miraculously, from the undergrowth onto a gravel road, where a battered-looking black car was pulled up on a grass verge. A fair-haired woman was sitting in the passenger seat, or seemed to be, until she honked the horn in a double greeting and put both hands on the steering wheel.

‘Thar she blows!’ he said, gleefully waving with the full sweep of his arm. ‘Our trusty Saab. She does look like a whale, I think, don’t you? Come and say hello to my wife; she’ll never forgive me otherwise.’

Before Jude had a chance to bolt, the woman was out of the car and striding towards them. And smiling with such warmth that Jude was hardly able to think.

The couple threw their arms around each other and kissed quickly on the mouth, before turning their attention to Jude.

‘What have we here?’ the woman said to her husband, then turned to Jude. ‘I do hope he hasn’t hypnotised you with his words, dear. He’s an unstoppable force once he gets going. Anyway, nice to meet you. I’m Sigrid, but you can me Sigi.’ She grabbed Jude’s hand and gripped it in a strong handshake. She was tall and strongly-built with a swimmer’s shoulders, but, despite her age, very beautiful.

‘Goodness gracious,’ he said, ‘I don’t even know this young lady’s name.’

‘Jude,’ said Jude wondering if she could also say, I’m Judith, but you can call me Jude.

‘Nice to meet you, Jude. This fool, in case he forgot to introduce himself, is Olof.’

‘My wife likes to remind me now and then that Olof is an anagram of fool,’ he said, chuckling and taking his wife’s hand.

‘Ah,’ Jude replied, and stood awkwardly transfixed by this pair, who might have been aliens from another planet, so different were they from anyone she’d ever known.

‘I caught her picking mushrooms,’ Olof said, ‘and she caught me picking oak galls!’

‘Well, well, a fellow forager! What did you find? May I see?’

It was then that Jude and Olof realised that the mushrooms, basket and all, had been left under the tree.

‘Oh,’ Jude said, ‘I’ll have to go back.’

‘No,’ Sigrid said. ‘It’s going to be dark soon.’

‘But my basket…my…’

‘But this is silly, you can come back for that tomorrow. Now, do you have far to go? A car?’

‘No,’ Jude said, miserably; oddly for her, tears pricked at her eyes.

‘Oh, helvete! See what you’ve done, Oli! We will, of course, give you a lift home. I may have to stop off on the way, but we’re not far.’

Sigrid opened the passenger side door, pulled the seat forward and Olof folded himself into the back.

‘Hop in,’ she said to Jude, in such a way as to brook no argument.

Jude obeyed, casting a glance at Olof, who was sitting with his long legs folded sideways.

Sigrid drove fast, overtaking cars and gunning the engine, until she suddenly swerved off the road and up a long, tree-lined drive. She came to a halt in front of a large detached house, then pulled up the handbrake fiercely.

‘Come on, you may as well come in for a coffee while I make my call. Then I’ll take you wherever it is you want to go… as long as it’s not Hammerfest!’

Sigrid hurried into the house leaving Jude to tip up her seat and allow Olof out of the car.

‘She rings her mother in Sweden every evening at the same time. You mustn’t take offence. It’s important.’

He went through the open door. ‘Do you take coffee?’ he asked. ‘Or something stronger, perhaps?’

Jude followed him though a dim hallway. The tiled floor had a geometric pattern of black, white, terracotta and blue. On the wall was a large abstract painting that seemed to throb with colour; splashes and broad strokes of orange, yellow, sky blue and red. As she passed by, looking through an open door into another room, she saw an upright piano and another abstract painting; in yet another room, there were floor to ceiling shelves of books.

‘Come through,’ Olof said. ‘Make yourself at home.’

Oh, how she would have loved to do exactly that! But instead, she entered the enormous kitchen and stood awkwardly by the big pine table, not daring to touch one of the many chairs, let alone sit on it. Olof was fussing with various cupboards and pots, arranging brown bread on a board, jars of pickles and mustard, knives large and small. From the monster fridge with a silver decal reading ‘Kelvinator’, he took a brown-glazed crock, and numerous mysterious items of different sizes wrapped in greaseproof paper. Tempting aromas of cheese and cold cuts began to drift towards her. Within her reach there was already a bowl of fruit: grapes, apples, oranges and bananas. She weighed up her chances of taking just one thing on the sly, eating it and not getting caught. She thought about poor Tantalus punished by the gods, never able to reach the fruit that hung above his head.

‘Oh, Olof, tell the poor girl to sit, why don’t you?’ said Sigrid, sweeping into the room. ‘Please, sit, eat. I simply must have something before I drop you home – is that all right?’

Gratefully, as if finally forgiven by the gods she’d offended, Jude sat and ate, and drank a tiny glass of a strong, clear spirit they said was called Aquavit. Before she left, Olof asked her to come to their lumber room, where, tumbled in a corner, were several willow baskets of different shapes and sizes. He dug one out and said she’d be doing him a favour if she’d take it away. When she protested, he insisted, saying it was entirely his fault that she’d left her own bag behind.

After Sigrid dropped her back at the cottage, Jude allowed herself to weep for all she’d lost and all she’d never had. ‘If wishes were horses beggars would ride,’ she remembered her grandmother saying bitterly, nearly every time she saw her. She didn’t understand the proverb when she was little and as she got older, she ceased to really hear it; now it came back to her with clarity and she found herself wanting to scream at the old woman, ‘So what? Stuff your horses and your beggars and just shut up!’

OLOF THE FOOL

Jude was woken at six the next morning by a loud hammering on her door. Her first thought was that it must be her father, wild and still drunk from the night before. Next, she wondered if it must be the police or the Welfare people come to drag her away.

As she crept down the stairs, her letterbox clattered open and a woman’s voice cooed, ‘Hel-loo-oo! Ju-ude, it’s Sigi. Rise and shine!’

Jude wrenched the door open, ‘What’s wrong?’ she asked, imagining terrible things.

Yet there was Sigrid smiling broadly. ‘Wrong?’ she echoed. ‘Nothing’s wrong. Are you not even dressed? Did you forget?’

‘Forget?’

‘Yes, Olof asked you for breakfast, didn’t he?’

‘No… at least I don’t think so.’

‘But he asked you to join us for the day? He was so looking forward to it. He could talk about nothing else last night.’

‘I must have forgotten,’ Jude lied.

‘He misses teaching so much. Now what did he call you… ah, yes, an apt pupil.’

‘I…’

‘Oh, no,’ Sigrid said. ‘He didn’t ask you, did he? He has been imagining our day out and what he planned to show you and tell you so much that it’s become real in his mind before even that first simple step of inviting you. He will be so cast down. Can you come? Will you come? Or do you have plans for the day?’

‘No. Or rather yes, I can come. I have no plans.’

‘Wonderful! I’ll wait in the car.’

Jude dressed as quickly as she could, fearing any delay would mean the invitation was snatched away. She would have liked to dress with more care, choosing something special or failing that something clean, but yesterday’s clothes were there already, thrown over a chair. She splashed her face with cold water, pulled a comb carelessly through her hair and brushed her teeth. Downstairs she pushed her feet into her shoes without unlacing them.

‘Ready?’ Sigrid asked brightly as Jude got into the seat beside her. Without waiting for a reply she set off, driving once more at high speed through the still-empty streets. In scarcely any time, Jude found herself once more approaching the door of the lovely old house and passing through the hall and into the warm kitchen where Olof stood by the enormous table, wearing a butcher’s striped apron amidst clouds of flour.

‘My dear girl!’ he said, seeing her. ‘I won’t kiss you as I’ve doughy hands.’ He held up both hands to show her; flags and tatters of stretchy dough adorned his fingers.

‘Here she is!’ cried Sigrid, coming into the room behind her. ‘Your apt pupil, all ready for the day!’

‘Indeed! And what a day we have planned. But first, breakfast!’

They sat together to eat. Just like a real family, Jude thought. Politely she ate yogurt for the first time, first dipping the furthest tip of her tongue into the dollop on her spoon.

All the time Sigrid was watching her with concern, but each time Jude returned her gaze, she smiled brightly to divert her.

Olof went to fetch the newspapers from the hall: The Times, The Guardian.

‘Your magazine came,’ he said.

‘Oh, good,’ Sigrid said, ‘pass it over.’

Jude expected it to be Nova or She or any one of those women’s glossy magazines, but it was The New Scientist. She tried not to show her surprise, but evidently failed.

‘How rude of us,’ Sigrid said. ‘Sorry, Jude, would you like a paper to read? How’s that bread doing, Oli?’

‘Nearly ready for the oven,’ said Olof from behind the open wingspan of The Times.

‘We have a guest, Olof. Why don’t you show her your latest experiment instead of lurking behind the newspaper like a true Englishman?’

As if struck by lightning, Olof leapt up and threw the paper onto the table.

‘What?’ he roared, his face distorted, terrible.

Jude shrank into herself. It had happened, what she had expected all along – the anger, the unstoppable rage over nothing. A wrong word, a wrong look, an object left out of place by a fraction of an inch, an official letter in the post, a stubbed toe…

Then Sigrid laughed.

Olof laughed.

Jude was frozen by an old fear; she sat rigidly, eyes wide, heart pounding.

Olof turned to Jude, smiling, but the smile fell away. ‘Dear girl, what’s wrong?’

Sigrid rushed to her side, put a hand on Jude’s forehead. ‘Are you unwell? Here, sip some water. Olof get the brandy!’

He hurried away to another room.

‘I thought… I thought he was going to hit you,’ Jude whispered.

‘No. NO! He would never… that was just playacting. Just fun.’

Olof returned and with trembling fingers Jude took the glass he offered her.

‘Olof! This poor child thought you were really cross, that you were going to hurt me. Say sorry.’

‘I am sorry. From the bottom of my heart. I would never, never… It is a game we play.’

‘For a time we were in a small theatre company. Just amateur, you understand, in Stockholm. Our friends know our japes and nonsense, but you… Will you be okay? Shall I drive you home?’

Jude shook her head so vigorously there could be no doubt about her answer.

‘Good. Very good. We’d be disappointed if it spoiled our day. We were going to drive out to the Gower, but perhaps you would rather go somewhere else? Somewhere you haven’t been?’

Jude had not been to the Gower very much, despite the peninsula being ‘on the doorstep’, as people said. Just once on a nature trip with the school, and a few times on the bus. The sad truth was, it might have been the moon, so out of reach was it for someone like her.

‘The Gower would be lovely,’ she managed to say, ‘but I forgot to bring any money.’

‘Money? What do you want money for? There are no shops, you know.’

‘No, I know, but…’

‘Really. You’re our guest. It will be a pleasure to have your company, won’t it, Olof?’

Olof was clattering about with the oven. Pulling the loaf from it and tapping the bottom of the bread tin. ‘Perfect,’ he declared. ‘Have you done the coffee for the thermos yet?’

Jude insisted on sitting in the back of the car, saying she’d more comfortable.

Sigrid drove at her usual high speed, but as they approached Fairwood Common, she slowed down considerably. Jude gazed out of the window taking it all in. The wild ponies, the sheep, the far-off vistas, the blue sky so big all of a sudden.

‘I’m sorry,’ she burst out, surprising even herself.

‘What’s that?’

‘I’m sorry that I got upset. It was just…’

‘You mustn’t apologise. We understand.’

How could they understand, Jude thought. No-one could.

AN APT PUPIL

Stepping out of the car at Rhossili they found a cold wind blowing in from the sea.

‘Will you be warm enough?’ Sigrid asked, opening the boot of the car. She dug around until she found what she was looking for. ‘Here,’ she said, ‘put this on. It is from Iceland.’

Jude took the heavy jumper from her. It was white with a sort of black houndstooth pattern.

‘Very traditional. Now you look like a proper bondflicka!’

‘What’s that?’ Jude asked, loving the sound of the word in Sigrid’s voice.

‘Bondflicka? Oh, a strong working girl.’

‘Oh.’

‘It’s a compliment.’

‘Ah,’ Jude said uncertainly.

They walked along the broad cliff path, Jude marvelling at the sheep grazing calmly at the perilous edges, then beyond them the wide sweep of the sands so far below. Ahead of them lay the Worm’s Head and the old coastguard hut.

‘We won’t go over the causeway to the island today. The tide’s just in by the look of it.’

‘Jude has been many times, I daresay,’ said Olof.

Jude didn’t contradict him. It seemed embarrassing to admit she’d never even been this far. A failure of imagination, or just stupidity or laziness.

‘The Red Lady of Paviland was buried here with great ceremony during the Ice Age. Of course, “she” turned out to be a man. What’s it – thirty thousand years ago? They found mammoth bones too. Hard to imagine. Perhaps he was your ancestor, Jude.’

‘Or yours,’ added Sigrid.

‘True, true. Because, of course, as you know, Jude, those early tribes spread out across the globe. I have a book you might like to see, The Bog People by Peter Glob. A much later period, that’s true. It’s a study of the nearly perfectly preserved men put in peat bogs during the Iron Age.’

‘And women.’

‘Yes, yes, men and women. Sacrificed, most probably, but much is unknown. When we get home, I will show you the book.’

‘Only if Jude is interested. Not everyone shares your passion for the ancient past.’

‘I’d love to see it,’ Jude said, concentrating more on the word ‘home’; with them she would have agreed to an evening poring over the telephone book.

‘We went to a lecture Peter gave in Copenhagen, and met him at the drinks reception afterwards. A charming man, handsome too.’

‘Apart from that smelly pipe he was constantly smoking.’

‘Oh, yes, I’d forgotten that.’

They passed very few people, but called ‘Good morning! Beautiful day!’ to all. Jude walked silently beside them, noticing how people responded warmly to them.

At the coastguard hut, Sigrid produced a camera and a tripod.

Leaning close to Jude, Olof said, ’Don’t imagine she’ll take a nice snapshot of us. Or indeed the Worm; it’s that hut she wants. The splendid isolation of it. Let’s look at this drystone wall instead.’

What Jude thought was sarcasm, turned out to be a simple statement. Olof stared at the wall, going closer at times, but mostly scanning it from a few feet away. Jude also looked, but she was stumped as to the reason.

‘See anything out of the ordinary?’ he asked, after fifteen or so minutes.

‘I don’t think so.’

‘Me neither,’ he concluded. ‘My theory, you see, is that with so much evidence of prehistoric activity nearby, it could be that old stones were reused by farmers. As you know, the famous bluestones of Stonehenge came from west Wales, so I’m always on the lookout for stones that don’t belong.’

Sigrid joined them. ‘There’s a fisherman’s shed down the cliff, too, but I’ll save that for another time. I think the weather’s on the turn.’

‘We should get around to Goat Hole sometime, too, see the Red “Lady’s” cave.’

‘Can you see her… him?’ Jude asked.

‘Oh no, not here. Not in situ. He was whisked off to Oxford.’

‘Oh,’ Jude said.

‘It’s desecration, plain and simple,’ Sigrid said. ‘Typical Western arrogance. A lack of respect that’s excused by progress and science. Anyway, I’m in need of coffee; let’s get going.’

They marched briskly back; the wind was gathering force, whistling in Jude’s ears and making conversation impossible. A huge thundercloud seemed to appear from nowhere and cold rain spattered down just as they got to the car.

The windows of the car steamed up while they sipped their coffee, so between that and the driving rain it seemed as if the ordinary world had gone away and they were on an alien planet. Jude herself felt like an alien. An outsider, never fitting in, never finding her place. She had no doubt that Sigrid and Olof had seen her loneliness, her awkwardness, her frowning intensity too, and taken pity on her. She did not dare to ask them anything about themselves, such as what had brought them to Wales. She assumed they must have something to do with the university.

‘Where now?’ Sigrid said, and it seemed as if the words were a question that had escaped from Jude’s mind. ‘I hoped the rain would have cleared by now. I’m not sure it’s the best for exploring the Salt House.’

‘Have you been there?’ Olof inquired pleasantly, peering at Jude from between the front seats.

‘I don’t think so. Is it a pub?’

Olof laughed as if Jude had made a witty remark.

‘No,’ Sigrid said, ‘it’s the ruins of a house where salt was dried and stored.’

‘Salt was valuable, wasn’t it?’ Jude said. ‘That’s where the word salary comes from.’

‘Did you study Latin at school?’

‘No, not really. Our English teacher used to talk about words, where they came from and all that.’

‘Ah, the tangle of language! Etymology is a fascinating subject.’ Jude thought etymology was the study of insects, but held her tongue.

‘Perhaps we should just go home,’ Sigrid said.

‘I can show you how I make ink!’

‘Only if you’d be interested, Jude. Oli thinks the world is as passionate about these obscurities as he is.’

‘I would like to see how it’s done,’ Jude said.

‘Excellent. Then the day won’t be wasted,’ Sigrid said.

‘No day with you is ever wasted, älskling.’

‘Fool,’ said Sigrid and she leaned over and kissed Olof, smack-bang on the mouth. ‘Off we go then; say if you’re cold in the back.’ She rolled her window down an inch and started the car. The windshield wipers began with a steady, squeaking rhythm. The cool air was refreshing, the green landscape flashed by as blurry as a watercolour painting.

CURIOUS PEOPLE

‘Do you keep a diary, Jude?’ Olof asked.

‘I used to. Then someone read it.’

Sigrid had disappeared to her darkroom, while Jude watched Olof slicing red onions.

‘This will be for Picklad rödlök.’

‘Pickled onions?’

‘Precisely. But how did you know that someone read your diary?’

‘Because he told me.’

‘He?’

‘He was furious. He yelled at me and tore it to shreds.’

‘I see. A boyfriend, was it? But what had you written? Tales of an illicit love affair?’

‘No!’

‘Will you pass me that glass jar, please.’

‘This one?’

‘Yes. That must have been upsetting, to have one’s private thoughts invaded. Then for him to destroy them. Such a vile betrayal of trust. I can’t imagine.’

‘But I…’

‘What? You deserved it? No, no. Now I’m going to boil the cider vinegar with sugar and water. In Sweden we have vinegar called ättika, but this will do. So was it your father, Jude?’

‘Yes. I hated him.’

‘I’m sorry. Is he gone now?’

Jude nodded cautiously; her father was gone and never gone, too.