The Glass Shore E-Book

Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: New Island

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

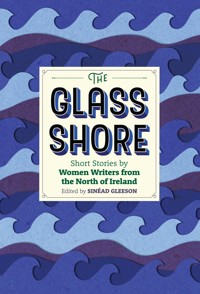

NEW PAPERBACK EDITION 2015 saw the publication of The Long Gaze Back: An Anthology of Irish Women Writers, edited by Sinéad Gleeson. The Long Gaze Back was widely acclaimed and went on to win Best Irish-published Book of the Year 2015 at the Irish Book Awards. More importantly, it sparked lively discussion and debate about the erasure of women writers from the literary canon. One question kept arising: where was the equivalent anthology for women writers from the north? The Glass Shore, compiled by award-winning editor, broadcaster and critic Sinéad Gleeson, provides an intimate and illuminating insight into a previously underappreciated literary canon. Twenty-four female luminaries — whose lives and works cover three centuries — capture experiences that are both vivid and varied, despite their shared geographical heritage. Unavoidably affected by a difficult political past, this challenging landscape is navigated by characters who are searingly honest, humorous and, at times, heartbreakingly poignant. The result is a collection that is enthralling, stirring and quietly disconcerting. Individually, these intriguing stories make an indelible impact and are cause for reflection and contemplation. Together, they transgress their social, political and gender constraints, instead collectively presenting a distinctive, resolute and impassioned voice worthy of recognition and admiration. Featuring stories by: Rosa Mulholland, Erminda Rentoul Esler, Sarah Grand, Alice Milligan, Eithne Carbery, Margaret Barrington, Janet McNeill, Mary Beckett, Polly Devlin, Frances Molloy, Una Woods, Sheila Llewellyn, Linda Anderson, Anne Devlin, Evelyn Conlon, Mary O'Donnell, Annemarie Neary, Martina Devlin, Rosemary Jenkinson, Bernie McGill, Tara West, Jan Carson, Lucy Caldwell and Roisín O'Donnell.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 504

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

THE GLASS SHORE

THE GLASS SHORE

Short Stories by Women Writers from the North of Ireland

Edited by Sinéad Gleeson

THE GLASS SHORE

First published in 2016 by

New Island Books

16 Priory Office Park

Stillorgan

Co. Dublin

Republic of Ireland.

www.newisland.ie

Editor’s Introduction © Sinéad Gleeson, 2016

Introduction © Patricia Craig, 2016

Individual Stories © Respective Authors, 2016.

‘The Harp that Once---!’ originally appeared inThe Shan Van Vocht, held by National Folklore Collection UCD. © Public domain. Digital content: © University College Dublin, published by UCD Library, University College Dublin <http://digital.ucd.ie/view/ucdlib:43116>

‘Village Without Men’ is fromDavid’s Daughter Tamar and Other Storiesby Margaret Barrington, reprinted by permission of Peters Fraser & Dunlop (www.petersfraserdunlop.com) on behalf of the Estate of Margaret Barrington.

‘The Girls’ by Janet McNeill reprinted with permission of David Alexander, executor of the literary estate of Janet McNeill.

‘Flags and Emblems’ is fromA Belfast Womanby Mary Beckett, © Mary Beckett 1980.

‘Taft’s Wife’ by Caroline Blackwood. Copyright © The Estate of Caroline Blackwood 2010, used by permission of The Wylie Agency (UK) Limited.

‘The Devil’s Gift’ is fromWomen Are the Scourge of the Earthby Frances Molloy, reprinted by permission of White Row (http://www.whiterow.net) on behalf of the estate of Frances Molloy.

The authors have asserted their moral rights.

Print ISBN: 978-1-84840-557-8

Epub ISBN: 978-1-84840-558-5

All rights reserved. The material in this publication is protected by copyright law. Except as may be permitted by law, no part of the material may be reproduced (including by storage in a retrieval system) or transmitted in any form or by any means; adapted; rented or lent without the written permission of the copyright owner.

British Library Cataloguing Data.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

New Island is grateful to have received financial assistance from The Arts Council of Northern Ireland (1 The Sidings, Antrim Road, Lisburn, BT28 3AJ, Northern Ireland).

Contents

Editor’s IntroductionSinéad GleesonIntroductionPatricia CraigThe Mystery of OraRosa MulhollandAn IdealistErminda Rentoul EslerEugeniaSarah GrandThe Harp that Once–!Alice MilliganThe Coming of Maire BanEthna CarberyThe GirlsJanet McNeillThe Countess and IcarusPolly DevlinThe Devil’s GiftFrances MolloyThe DiaryUna WoodsCapering PenguinsSheila LlewellynThe TurnLinda AndersonCornucopiaAnne DevlinDisturbing WordsEvelyn ConlonThe Path to HeavenMary O’DonnellThe NegotiatorsAnnemarie NearyNo Other PlaceMartina DevlinThe Mural PainterRosemary JenkinsonThe Cure for Too Much FeelingBernie McGillThe Speaking and the DeadTara WestSettlingJan CarsonMaydayLucy CaldwellThe Seventh ManRoisín O’DonnellAcknowledgementsEditor’s Introduction

Sinéad Gleeson

Books sometimes beget books. Something comes into being and, down the road, reaches out to other work. In 2011, sitting in a room crammed with books in New Island’s office, I mentioned to the editor there how much I admired Evelyn Conlon’s all-female short story anthology, Cutting the Night in Two. Originally published in 2001, another volume felt long overdue.

When I was asked to take on the project, I agreed. It was daunting, certainly, and felt like a lot of responsibility, but I was excited at the prospect of finding new writers and resurrecting older ones. It was a long process of recovery, of what a friend called ‘literary archaeology’. Not just to seek out writers that had all but vanished, but to physically locate texts and work of a suitable length. The result was The Long Gaze Back: An Anthology of Irish Women Writers, and the response to it far exceeded any expectations myself or New Island had. The collection started many conversations about omission and exclusion, about the dominance of male voices in the Irish literary canon, and the sheer volume of writing by women that had been overlooked and marginalised. The anthology won an Irish Book Award in the same month that the Waking the Feminists controversy began. It seemed that in 2015, we were still having conversations about women’s cultural exclusion and how casually it can happen.

I chaired many discussion events for The Long Gaze Back, including two panels in Belfast. At both talks, many people asked questions or approached me afterwards to ask, ‘Where is our book?’ Lucy Caldwell contributed to both events, and also has a new story in The Glass Shore. She told me of growing up in Northern Ireland and hearing all aspects of life – politics, society and particularly culture – dominated by male voices. She encouraged me to take on this project and give a voice to the women writers who had been left behind. I thought of the threaded line between Cutting the Night in Two and The Long Gaze Back, and believed that a new book representing a range of Northern Irish voices needed to happen. In the weeks after Belfast, I spoke to countless writers and women who reaffirmed this absence. While not solely short stories, Ruth Carr’s excellent The Female Line: Northern Irish Women’s Writers (1985) is a diverse mix of poetry, memoir and novel extracts. It is an important book for many reasons, not least because it represented Northern Irish women writers at a time when there was little visibility.

The Long Gaze Back includes six Northern Irish writers in a collection of thirty stories spanning several centuries. The Glass Shore contains twenty-five stories and is structured in a similar way. There are ten deceased writers, the earliest being Rosa Mulholland (born in 1841), and six more of the writers were born in the nineteenth century. Some predate the existing border in the North, which is one of many reasons for including the nine counties of Ulster in this anthology. All anthologies are partial, for reasons of space, and I hope these stories make readers search out more work by each writer, and by other Northern writers. In these pages, there are fifteen living writers, and the youngest – Roisín O’Donnell – was born two years before The Female Line was published. As with The Long Gaze Back, I felt it was important that writers contributed new and unpublished work. The writers were given a word count, but no thematic guide. Given the geographic focus of this book, there may be an expectation of the work: that it would deal with conflict or religion. Some stories do, but many engage in a broader kind of politics: of the personal, of bodies, of borders.

These stories exist on their own terms. They talk of movement, belonging and expectation. They are set in cities, and on the coast, in Ireland, and outside it. Characters negotiate relationships, missed chances, love, social exclusion, ghosts, history and where we all come from. They look back as well as forwards. Patricia Craig, in her excellent introduction, outlines many of the stories, including their commonality and their distinctions.

In terms of women’s writing all over the island of Ireland, I hope there are more anthologies, new editors and exceptional work – like the stories here – to come.

Sinéad Gleeson, Summer 2016

Introduction

Patricia Craig

Writing in 1936, Elizabeth Bowen ascribed a kind of ‘heroic simplicity’ to the contemporary story, along with a ‘cinematic’ conciseness or compression, which freed it from ponderousness. It was, she thought, in its current form, ‘a child of the twentieth century’. True: but the mid-century story had roots in the past, and a strong link to the future. Sinéad Gleeson’s previous anthology of Irish women writers, The Long Gaze Back (2015), stretched all the way to Maria Edgeworth, and came right up to the present with authors such as Anne Enright and Éilís Ní Dhuibhne. Its present-day section added up to a stunning display of twenty-first-century preoccupations and techniques, while earlier inclusions (the stylish Maeve Brennan, the judicious Mary Lavin) gave a due thumbs-up to their predecessors.

The Long Gaze Backcovered the whole of Ireland; now Sinéad Gleeson has turned her attention to the North (the geographical North, that is, with Donegal and Monaghan well represented).The Glass Shorefollows a similar format to the previous undertaking: most of the stories brought together here have been commissioned specially for the anthology, while a few older contributions (some much older) testify to a tradition of Northern women’s writing which gets to grips, forthrightly or obliquely, with all kinds of topical concerns. The earliest piece in the book, ‘The Mystery of Ora’ by Rosa Mulholland, exploits ‘sensation’ to the full. Mulholland was born in Belfast in 1841, but writes about an overwrought Irish maiden on a wild mountainside in the West, a traveller, some diabolical machinations, a prisoner on an island, and so on, in a thoroughly professional manner. Two further nineteenth-century stories stand out as contributions to what was then an emerging ‘New Woman’ genre, as defiant feminists and Suffragettes went kicking over the traces. The name of Sarah Grand, indeed, is almost synonymous with this genre; and in ‘Eugenia’ she preserves a cool detachment, a hint of mockery, while pursuing a satisfactorily feminist outcome. If her story is a bit wordy, as well as worthy – well, we can put it down to the fashions of the day. Her contemporary, the wonderfully named Erminda Rentoul Esler (‘An Idealist’), is likewise in the business of presenting a positive plan of action for brainy girls to follow.

Other modes were available to past Irish writers. Margaret Barrington, for example, has a stark account of female stoicism and expedience in remote Donegal in ‘Village without Men’, while Ethna Carbery in ‘The Coming of Maire Ban’ succumbs to a romanticism of the peasant-macabre. ‘The Harp That Once–!’ by Alice Milligan is set in Mayo during the final episode of the rebellion in 1798, and features an intrepid heroine who delays a band of Redcoats with her harp-playing, while, behind the scenes, defeated rebels make good their escape. Alice Milligan, as it happens, is not only a contributor to The Glass Shore, but the subject of one of its finest stories, ‘No Other Place’ by Martina Devlin. Here she is in old age, tending roses in the garden of her Church-of-Ireland rectory outside Omagh on the eve of the Second World War, while her past work – all her literary and nationalist activities – are deftly delineated.

‘No Other Place’ is beautifully judged in its effects and atmosphere, but it is not alone in this. Each of The Glass Shore stories embodies a unique angle of vision; the range of styles and tones is very striking. At the same time, reading through the anthology, what you’re aware of is a unifying assurance and expertise. Moreover, as with all properly thought-out collections, each inclusion gains in impact from the presence of others. These are all splendid examples of the Irish short story, irrespective of gender – though it seems a balance still needs to be adjusted between male and female, which justifies the nature of the project.

You will find touches of the surreal or supernatural here, exhilarating wryness, ingenuity and depth of feeling. An impressive discovery, Janet McNeill’s ‘The Girls’ appears here in book form for the first time, and is characteristically insightful, economical and decorous; while Caroline Blackwood (‘Taft’s Wife’) is sharp and astringent as ever. And, because ofThe Glass Shore’s Northern orientation, the sense of sectarian imperatives is never too far away. Transgressions against a neighbourhood code of conduct are central to Mary Beckett’s masterly ‘Flags and Emblems’, and to Rosemary Jenkinson’s poignant and unsettling ‘The Mural Painter’. The Troubles, too, are an inescapable fact of life, as in Linda Anderson’s compelling ‘The Turn’ – set in a hospital ward in Cambridge at the present time, but harking back to Belfast before the ceasefires, and further back to childhood summers and ‘forlorn trips to Ballyholme and Groomsport’.

Tara West’s ‘The Speaking and the Dead’ comes replete with Belfast repartee, undercut by sadness and desperation. In Lucy Caldwell’s skillful, level-headed ‘Mayday’, a student at Queen’s University in Belfast finds herself in an age-old predicament. Perhaps the most shocking story in the book – shocking, because truthful and dispassionate – is the late Frances Molloy’s ‘The Devil’s Gift’, which recounts without recrimination the experiences of a postulant in a mid-twentieth-century Irish convent. You are left aghast at the inhumanity, not to say lunacy, evoked in this searing account. In a lighter vein, the captivating ‘Settling’ by Jan Carson takes a quizzical look at a moment of misgiving in its heroine’s life, with the safety of the past opposing the liberating uncertainty of the future.

Painful and playful social comedy; astute documentation and comment; a destructive impulse afflicting a returned prisoner of war; a brisk account of the dangers of undue empathy; a warning about unearned confidence in a foreign situation – or indeed, about interfering in another’s domestic circumstances; a strong engagement with myth and magical realism; an enigmatic approach; an out-and-out zaniness; all these you will find wonderfully represented in these pages. And more. Polly Devlin’s debonair and sparkling ‘The Countess and Icarus’, with its discreet Northern Irish narrative voice, takes us into a realm of urbanity and insouciance (with an episode of high comedy towards the end); while in Anne Devlin’s ‘Cornucopia’, a vividly impressionistic world comes into being, all subtle colouring and pungent connections.

The North of Ireland functions as a theme, a setting, a background, a place to own or repudiate, to wonder at or take for granted – or simply as the birthplace of the authors assembled so felicitously by Sinéad Gleeson. Home ground, broken ground, a place apart: view it as you will. Politically (six counties), it is inescapably cut off, and even in the geographical sense it has a distinct outline – and one ofThe Glass Shorestories, in particular, has a special resonance in relation to borders and borderlands, lines drawn, ironies observed and symbols upheld. It is Evelyn Conlon’s idiosyncratic ‘Disturbing Words’, which also contains pointed reflections on death and emigration, locality and protest, all intriguingly intertwined. It rivets the attention.

But whatever your aesthetic, intellectual or imaginative requirements of the short piece of fiction, you will find much to ponder here, much to relish and applaud.

Rosa Mulholland

Rosa Mulholland was born in Belfast in 1841, and after encouragement from Charles Dickens – who admired and championed her work – became a writer. She was a prolific author of novels, novellas, dramas, and poems, including Narcissa’s Ring, Giannetta: A Girl’s Story of Herself, The Wicked Woods of Toobereevil, The Wild Birds of Killeevy, The Late Miss Hollingford, Marcella Grace, A Fair Emigrant and The Story of Ellen. She wrote several short story collections, including The Walking Trees and Other Tales, The Haunted Organist of Hurly Burly and Other Stories, Marigold and Other Stories and Eldergowan … and Other Tales. Her short story, ‘The Hungry Death’, was included by W.B. Yeats in his collection, Representative Irish Tales, and is said to be the inspiration for his play Cathleen ni Houlihan. She died in 1921 in Dublin.

The Mystery of Ora

There is something inexplicable in the story, but I tell it exactly as it happened.

Born to the exception of wealth, certain casualties of fortune swept away my possessions at a blow. I was young enough to relish the thought of work for three years unremittingly, till my health began to feel the strain, and I resolved to take an open-air holiday. A friend who was to have accompanied me changed his mind at the last moment, and I set out alone.

I chose to visit the wildest parts of the west coast of Ireland, and was rewarded by the sight of some of the finest scenes I had ever beheld. Keeping the Atlantic on my right, losing sight of it for a time, and again finding it when some heathery ascent was gained, I walked for two or three days among lonely mountains, accepting hospitality from the poor occupants of the cabins I occasionally met with. It was fine August weather. All day the hill peaks lay round me in blue ether; every evening the sun dyed them first purple, then blood-red, while the solitary slopes and vales became transfigured with a glory of colour quite indescribable. At night the solemn splendour that hung over this wilderness kept me awake, enchanted by the spells of a more mysterious moon than I had ever known elsewhere.

One morning I began to cross a ridge of a mountain that separated me from the sea shore, and was warned by the peasant whose breakfast of potatoes I had shared that I must travel a considerable distance before I could meet with shelter or food again.

‘Ye’ll see no roof till you meet the glass house of ould Collum, the stargazer,’ he said. ‘An’ ye needn’t call there, for he spakes to no one, an’ allows no man to darken his door. Keep always away to yer left, an’ ye’ll get to the village of Gurteen by nightfall.’

‘Who is this Collum, who allows no man to darken his door?’ I asked.

‘Nobody rightly knows what he is by this time, sire; but he was wanst a dacent man, only his head was light with always lookin’ up at the stars. He built himself this glass house, for all the world like a lighthouse; an’ so far so good, for it did turn off a lighthouse on them Eriff rocks; that’ll tear a ship to ribbons like the teeth of a shark. An’ there he did be porin’ into books an’ pryin’ up at the heavens with his lamp burnin’ at night; an’ drawin’ what he called horry-scopes, thinkin’ he could tell a man’s future an’ know the saycrets of the Almighty. His wife was a nice poor thing, an’ very good to travellers passing the way, an’ his little girl was as gay and free as any other man’s child; but somehow there’s no good to be got of spyin’ on the Creator; an’ after his wife died he got queerer an’ queerer, an’ fairly shut himself up from his fellow cratures; an’ there he bes, an’ there he remains. An’ the daughter seems to have grown up as queer as himself, for she niver spakes to nobody, not these last three or four years, though she used to be so friendly.’

‘Well,’ I said. ‘I shall keep out of old Collum’s way,’ and I started for my long day’s walk.

I had walked a good many hours, and had crossed the steep ridge that separated me from the seaboard; had lain and rested at the full-length in the heather, and gazed in delight at the magnificent view of the Atlantic, with its fringe of white, low-lying, serrated rocks, interrupted here and there by a group of black fortress-like cliffs. I had begun to descend the face of the mountain by a winding path when I became conscious of something moving at a little distance from me. Sheltering my eyes from the sun, I saw the figure of a woman against the strong light – a figure that came towards me with such a swift, vehement movement that it seemed almost as if she had been shot from the blazing sky across my path. She put both her hands on my arm with a grasp of terror, and then stammered some incoherent words, extended one arm, and pointed wildly to the sea – that serene ocean, which a moment ago had looked to me like the very image of majestic peace, with its happy islets sparkling on its breast. What was there in that smiling storm-forgetting ocean to excite the fear of any reasonable being? My first thought was that she was some poor maniac whose all had gone down out there on some stormy night, and who had ever since haunted the scene of her shipwreck, calling for help. I could not see her features at first, so dark was she against the strong light that dazzled my eyes.

‘What is the matter?’ I asked. ‘What can I do for you?’

As I spoke, I shifted my position so that I was in the shade while the light fell upon her; and I saw that she was no mad woman, but a very beautiful girl, with a face full of strong character and vivid intelligence. The look in her eyes was the sane appeal of one human creature to another for protection; the white fear on her lips was a rational fear. The firm, gracious lines of her young countenance suggested that no mere cowardly impulse had caused her to seize my arm with that agonised grasp.

As she stood gazing at me, with that transfixed look of terror and appeal, I saw how very beautiful she was, with the sunlight pouring round her and almost through her. Her glowing hair, which I had thought was black, had flashed into the warmest auburn, and lay in sunny masses on her shoulders; her eyes, deep grey and heavily fringed, glowed from her pale face with a splendour I had never seen in eyes before. She was poorly and singularly dressed in a faded calico gown and an old straw hat, tied down with a scarlet handkerchief; but even as she stood, nothing could be more perfect than the artistic beauty of colour and form which she presented to my astonished eyes. Almost unconsciously I noticed this, for all my mind was engaged with the expectation of what she had to tell me, with the awe of that look of the living imploring anguish, and the wonder as to what that message could be that she seemed to be bringing me from the ocean.

As she did not speak I repeated my question: ‘What is the matter? Tell me, I beg, what can I do to help you?’

Her eyes slowly loosened their gaze from my face, her arm fell to her side, a slight shudder passed over her, and she turned away.

‘Nothing.’ She almost whispered the word, and moved a step from me.

‘That is nonsense,’ I said, placing myself in her path. ‘Pardon me, but you are in some trouble – in some danger, and you thought I could save you from it, or at least help you. Let me try. Let me know how I can serve you.’

‘I cannot tell you,’ she murmured, and then raised her eyes again to mine with another wild look full of unutterable meaning. Behind her gaze there seemed to lie a lonely trouble, which peered out from its prison house and asked for human sympathy, but was crossed and driven back by a cloud of unearthly fear. I thought so weird a look had never passed from one living creature to another.

I felt puzzled. So sure was I of the reality of her forlorn anguish that I could not think of passing on and leaving her to be the victim of whatever calamity threatened her under the shadow of this lonely mountain. And I felt, by instinct, that the womanly weakness within her was clinging to me for protection in spite of the steadfast denial of her words.

‘I am a stranger,’ I said. ‘And you are afraid to trust me; but I give you my word, I am an honourable man – I will not take advantage of anything you may tell me here.’

Her lips quivered and she glanced at me wistfully. She looked so young – so piteous! I took her passive hand firmly in mine and said again, ‘Trust me.’

‘I do, I could,’ she faltered. ‘But oh! It is not that. It must never be told. I dare not speak.’

She turned slowly round, and her eyes went fearfully out to sea, wavered towards the cliffs, and lit on a glittering point among them; then she snatched her fingers from mine with a wail of terror, and, dropping to her knees before me, hid her hands in her face and wept.

I waited till her agony had spent itself, and then I raised her up gently and tried to reason with her. But it was all in vain. No confidence would pass her lips. She became every moment firmer, colder, more controlled. All her weakness seemed to have been washed away by her tears, and yet the calm despair on her soft face, bringing out its strongest lines of character, somehow touched me more than any complaint could have done.

‘I thank you deeply,’ she said. ‘You would have helped me if you could. Go your way now, and I will go mine.’

‘I will at least bring you to your home,’ I said. ‘Where do you live?’

‘There,’ she said, pointing to the glittering point on the rocks.

I shaded my eyes and looked keenly through the sunlight, and suddenly it flashed upon me that yon glitter came from ‘old Collum’s glass house’, and that this was his daughter.

‘Is your father’s name Collum?’ I asked.

A sudden change passed over her – I knew not what – like an electric thrill.

‘That is his name.’

‘And he lives in yonder observatory?’

‘It is our home,’ she replied after a pause.

‘Let me accompany you,’ I said.

‘No one comes there; he – he does not make anyone welcome. I beg, you will not mind me; I am accustomed to roam about alone.’

‘I have walked a long way,’ I said after a few moments’ reflection, ‘and I am tired and hungry. I hope you will not forbid my throwing myself on your father’s hospitality for a few hours. I cannot reach the nearest village before nightfall.’

This clever appeal of mine had its effect. She no longer urged me to leave her, though a painful embarrassment hung upon her. Under other circumstances, delicacy would have forced me to relieve her from this, but I had made up my mind to leave no means untried to help her. I had a strong suspicion that old Collum was cruel to his child, and that she feared to let a stranger witness his ill-conduct. I determined to discover for myself, if I could, what sort of life he forced her to lead. We descended the mountain silently together, and, crossing a difficult passage of rocks, arrived at old Collum’s house.

It was a curious, old, grey, weather-beaten building, wedged into and sheltered by the cliffs, and looking as if in some early age it might have been carved out of their grim masses. The observatory was a much newer erection – a round tower with a glass chamber at its top, resembling a lighthouse to warn mariners from these dangerous rocks. The house was of two storeys – three rooms below and three above, and we ascended a narrow spiral staircase to the higher chambers. My companion led the way to an apartment in the front – a dimly-lit, gloomy place, with two small windows set high in the wall from which nothing could be seen but two square spaces of ocean. The interiors of this room showed how very ancient the building must be. It had, in fact, been built as a hermitage by monks in an early century. The stone walls, made without mortar, had never been plastered, and the rough, dark edges of the stones had been polished and smoothed by time. Upon them hung a map of the world, one or two sea charts, a compass, a great old-fashioned watch of foreign workmanship, ticking the time loudly, and a few pieces of ancient Irish armour and ornaments dug out of a neighbouring bog. The floor was paved with stones, worn into hollows here and there, and skins of animals were strewn over it. The fireplace was a smoke-blackened alcove, and across it, sheltering its wide nakedness, the skin of a seal was hung, fixed in its place by an ancient skein, or knife of curious workmanship. On the rude hearthstone lay the red embers of a peat fire; and though an August sun was glowing in the heavens, the fire did not seem out of place in the chill of this vault-like dwelling.

As we entered, my companion cast a hurried glance into the room and seemed relieved to find it unoccupied. She threw off her hat and, opening a cupboard, began to prepare the meal which I had begged of her. All her movements were graceful and ladylike, and her beauty seemed to take a new character as she made her simple housewifely arrangements. Excitement and exaltation were gone from her manner, wildness and brilliance from her looks. No longer glorified by the sunlight, her hair had ceased to flash with gold, and had darkened to the blackness in the shadows of the room. Her downcast eyes expressed only a gentle care for my comfort and, as I watched her with increasing interest, a faint colour came and went in her face.

I took up a curious, old drinking cup of gold that she had placed on the table. On it was engraved the word ‘Ora’, and I asked her what it meant.

‘It is my name,’ she said. ‘The cup was found not far from here, and my father put my name upon it.’

Now, when she said this, there was wonder in my mind, not that she bore so strange and original a name, but because the words ‘my father’ were pronounced in a tone of such mournful and compassionate lovingness as to startle away all my preconceived notions as to the reason of her unhappiness.

‘Perhaps, if not wicked, he is mad,’ I thought. ‘And she is afraid of having him taken away from her.’

As I pondered this thought with my eyes fixed on the door, it opened, and a sallow, withered face appeared, set with two dull, black eyes, which fastened in blank astonishment on my face. ‘Collum the madman!’ was my mental exclamation on beholding this vision; but as the door opened farther, and a figure was added to the face, I saw that the intruder was a woman.

Ora turned to her, and raising her hands, talked to her on her fingers; then as the old creature began to make up the fire, said to me: ‘She is deaf and dumb, but a faithful soul, and all the servant we have. She gets our messages, fetches our provisions, and does little things that I cannot do myself.’

‘A strange household,’ I reflected. ‘An aged man, a deaf and dumb crone, and this beautiful, living, vigorous creature! Outside, the wilderness of the mountain and ocean. What a place – what company for Ora on winter nights!’

I said aloud: ‘And you, and she, and your father, are really the only dwellers in this lonely spot?’

She glanced up quickly, and a shudder of agitation passed over her, such as I had seen before. She did not reply for a few seconds, and then she said in a low, pained voice:

‘There are only three of us.’

A most distressing feeling came over me – a conviction that the girl was answering me with a wary reserve, veiling her meaning so that, while she did not speak absolute untruth, she resolutely kept something hidden from me. Everything about her persuaded me that this was done against her will. Her eyes expressed a candid nature; her manner trusted me, except at moments when my words jarred on the secret chord of anguish. Some terrible dread made her treat me at such moments as an enemy.

I sat at the table, and she waited upon me, serving me with an anxious care that made me feel ashamed of the pretence which had thrown me on her hospitality as a hungry man. My meal over, I felt that she would expect me to depart; and as I ate I pondered as to how I could contrive to remain in old Collum’s dwelling.

I was resolved not to go without making his acquaintance – yet how was I to force myself into the old man’s presence? Even as the thought passed my mind my question was answered. The door opened, and the master of this strange domicile appeared.

My first thought was that I found him much younger, keener, more vigorous and wide-awake than I had expected. Despite his long white hair, beard, and eyebrows, I saw at once that he was not a very old man; even his manner of opening the door, and the step with which he entered the room, gave one the idea of physical strength in its prime. There was no droop of the dotard about his features or figure – no dreamy, absent look of the stargazer in his fierce black eyes – no lines of abstracted thought upon his cunning brow. As he entered the room, not expecting to see me, I saw him just as he was– in all his reality; and I felt at once that had he known I was there he would have presented a different appearance. I seemed to know this by instinct, as one does sometimes divine certain things, by a flash of intelligence, in the first moment of meeting with a fellow creature.

As he stood in the doorway, looking at me with rage in his eyes, I saw his soul unveiled; the next moment – how or why I knew not – I beheld (my gaze having never been withdrawn from his face) a different being. The tension of his figure slackened; the lines of his face lengthened and weakened; the shaggy grey brows veiled the languid eyes; the forehead had assumed the look of the forehead of a visionary. He flung himself on a seat, and said feebly: ‘Excuse me, sir, but I did not know that our poor dwelling was honoured by the presence of a guest. Ora, my dear, you ought to have told me.’

Ora was behind me, and so intent was I upon watching the strange being before me that I did not look to see how she had taken this address. Besides, something warned me that it would be better to notice her as little as possible in her father’s presence. Striving to overcome the extreme repugnance I felt to my host, I said: ‘It is I who ought to apologise for my intrusion, but’ – here it seemed to me that I felt the thrill that quivered through Ora standing behind me – ‘but finding myself a complete stranger in need of rest and food in this lonely region, ventured to throw myself on your daughter’s hospitality. I am afraid, indeed, I forced myself upon her kindness.’

‘You are welcome, sir,’ he said. ‘Welcome to all we have to give. We live out of the world, and have little to offer to those who are accustomed to better things.’

His civil speech seemed to clear difficulties from my path, only to put greater ones in my way. That this wily man had, as well as his daughter, a secret to guard, was an established fact in my mind. That cruelty to her was not the whole of it I felt sure. Whether his civility was proof that he feared, or did not fear, detection by me, I could not at that moment decide, but put the question away for after consideration, along with another fact that I had noted without weighing what its value might be. The man spoke with a foreign accent, and with a manner which suggested that English was not familiar to him, and had been learnt late in life. He was of foreign workmanship, as surely as was the quaint old watch that ticked so loudly over the rugged fireplace.

As I talked to my host I studied the name on my drinking cup more frequently than his countenance. Something warned me that he would not endure anything like scrutiny; at the same time, I felt that I was undergoing a searching examination from the keen, cruel eyes half hidden under their drooping eyelids.

‘You are an Englishman, I suppose?’ he said.

‘Yes.’

‘And have never been in this country before?’

‘Never.’

‘And in all probability what you see of it in this holiday will be enough for you. You will hardly come back.’

This was said with an affectation of carelessness which would have imposed upon me had suspicion not been aroused within me.

‘Nothing is more unlikely than my return.’

As I said this, my conscience smote me, for I already felt that I could never more be entirely indifferent to the country which held Ora. The answer pleased him, however. There was a certain relief in his voice which I felt, and this encouraged me to make a bold stroke towards attaining my own purpose.

‘I am going to make a request,’ I said, ‘which I hope you will not think impertinent. This bit of coast scenery is so beautiful that I feel great longing to explore it further. I could not do so unless you will be so very good as to allow me to return here in the evening, and give me shelter for the night. I am well aware there is no dwelling in the direction I would take, and my health is not good enough for sleeping out of doors.’

I prolonged my speech after my request was made to give him time to prepare his answer; and I forbore to raise my eyes to his so that he might have a moment to quench whatever light of ire my audacity might happen to call into them. There was a slight pause, which told me my precaution had not been an unnecessary one, but when I looked up his face was placid and bland.

‘You are welcome,’ he said, ‘to what poor accommodation we can offer. Ora, let a room be prepared for this gentleman.’

I thanked him, and took my hat to go upon the excursion I had so newly designed. My host also rose and prepared to leave the room with me.

‘The old owl must go back to his nest,’ he said, with an attempt at pleasantry. ‘I am a dabbler in astronomy, an observer of the stars, and my days pass in making calculations. My observatory is my home. When I entered the room some time ago I was irritated beyond measure by a problem, the solution of which still eludes me. A little society has soothed me, and I shall return to my labours refreshed.’

This speech convinced me more than ever that he was an imposter. Not only had his words of information about himself a false ring in them, but his apology for his appearance in the moment when he had stood unveiled before me revealed a depth of consciousness which was betrayed by the effort to hide it. If anything had been wanting to complete the impression made by him upon me, it would have been supplied by the evil look which he turned upon Ora as he left the room. This look he, of course, intended to be unseen by me, and I was thankful that my interception of it had been unperceived. It was a significant look of warning, and contained a threat.

He went to his observatory, and I took my way over the jagged rocks along the sea shore, thinking deeply over all I had seen and heard.

It seemed to me that I had to sum up a number of contradictory evidences. That old Collum was not the visionary nor the stargazer which public report and his own representations declared him to be, was to me past doubting. That he had some heavy stake in this lower world, and was playing a part to win it, I believed, upon the strength of my own observations. Yet what object was to be gained by a life of such entire exclusion as his? The wildest ideas occurred to my imagination as to the possibilities of leading a criminal life in this wilderness; and were rejected almost as quickly as they took shape in my mind. His well-known inhospitality forbade the supposition that he could be a waylayer of travellers; and besides, had he been a murderer, Ora would not have stayed by him. She was free to roam where she pleased, and could have easily escaped to the nearest town as she could have climbed the mountain upon which she had met me. It was more likely that he might be a forger, and an undertaker of secret journeys into the world and back again to his den. Could her knowledge of his evil life account for her conduct? I thought it might and yet, having granted this, I still felt that there was a mystery behind him which I could not unravel. One moment I felt convinced that Ora hated and feared him, and that it was from him she would have appealed to me for protection; the next I remembered the accent of love with which she dwelt on the words ‘my father’, uttering them in a tone that was crossed by neither shame nor terror. And another point remained in my thoughts, though I knew not what conclusion I could draw from it. The man was of a foreign nation. I believed that he was not a European. True, my informant might have overlooked this fact when giving me his slight sketch of the unloved recluse, but from his name I had concluded he was an Irishman. ‘Collum’ I had supposed must be a namesake of St Columb; but of course, it might as easily be a corruption of some difficult Eastern word. From an Irish mother, Ora might have inherited her wonderful grey eyes and tender bloom, together with a might and heart as beautiful as her exquisite face.

The only result my cogitations produced was a feeling of satisfaction that I was going to pass one night at least under old Collum’s roof. I acknowledged to myself that there seemed very little likelihood of my being thus enabled to make any discovery; but the vague hope that during the next twenty-four hours I might find some faint clue to Ora’s mystery cheered me in spite of reasonable probability. I felt no pang of conscience at the thought of playing the spy upon my host. The one fact that remained clear in my mind regarding him was that he was a criminal who ought to be detected, whose existence blighted the life of the innocent girl who had the misfortune to be his child. And then my thoughts wandered from him and rested exclusively on Ora.

As I lay upon the rocks with my hands clasped behind my head, gazing out to sea, my eyes roamed over the numerous islands that lay scattered on its bosom for miles towards the horizon. Some looked large enough to support life, others were mere clusters of rocks; yonder one was gleaming like an emerald in the sun and seeming to invite the tired traveller to a sea-girt paradise, while over there another lowered, making a spot of sinister gloom on the smiling ocean. One that bore this latter character had a particular fascination for me. Its jagged rocks were like cruel teeth; it showed no cheerful fleck of green even when the sun touched it a moment and fled away. It seemed always in a shadow, and had a fierce gloom in its aspect that made one shiver. ‘All that enter here leave hope behind,’ I murmured, looking at it, and fancying it might well be the home of despairing spirits.

Birds were wheeling above it, and as I watched them, now black in the shadow and now white in the sun, I fell into a sort of dream – slumbering lightly, yet never losing the consciousness of where I was. I thought I heard the birds talking loudly to each other, and they talked of Ora.

‘Pluck her out of yonder dungeon,’ said one, ‘and carry her far over the sea!’

‘I cannot,’ said the other; ‘she is chained to the rock. Her father has chained her, and she will not tell.’

I started out of this dream to find that the sun had set, and resolved to return at once to the observatory. When I arrived, the door of the house lay open, and I went in without seeing anyone, and ascended the winding stone stairs, which did not creak under the foot.

In the room where I had left her, Ora was sitting alone. Outside it was still daylight, but in this gloomy chamber with its small, high windows, dusk had long set in, and a small lamp burned on the table, throwing a heavier darkness into the corners around it. The young girl sat by the lamp, poring intently over a book. The lamplight fell full on her face; and on that beautiful face was such a look of horror as it froze my blood to see. So absorbed was she that she did not perceive my approach, and I paused involuntarily, pained at seeing her suffering soul thus laid bare before me once more. Surprise deprived me for some moments of the power of speech. To find Ora a student was about the last thing I should have expected. To see her buried in a study which, from the expression of her face, I could not but fancy in some way connected with the woe of her life, was a still greater cause for amazement. Could she be conning some task which had been set her; or striving to forget in the pages of a book moments of terror which were only just past? But no; as she read, all her mind, all her being, were engaged with what the book conveyed to her; and as the moments passed, that fearful, indescribable look grew and grew on her face, till at last she raised her eyes and fixed them on vacancy with a gaze which seemed to threaten madness.

I could not bear it any longer.

‘Ora!’ I cried, touching her shoulder, ‘for Heaven’s sake, tell me what horrible thing you are looking at!’

She started violently, and let the book fall, put out her arm to bar my taking it up, and then sank back in her chair, exhausted by conflicting feeling. As before, I seemed to feel her passionate desire to confide in me – a desire struggling in the chains of her deadly fear. I gently put away her hand and took up the book.

‘Let me look at it,’ I said. ‘What harm can it do? You shall not tell me anything but what you please. The book can surely betray no secrets.’

She bent her head, and I opened the book. It was old and worn, the cover worm-eaten, the pages yellow and brown with time. The type was so strange that at first sight it seemed to be written in a foreign language; but as my eye became accustomed to it I was able to read.

It was a book on necromancy, treating the power of the Evil One, and of the mighty and terrible things he enabled those to do who leagued themselves with him and played into his hands. It was written with a certain force of imagination and diction, and, apparently, a thoroughness of faith in what it set forth, which was calculated to exercise an almost fiendish influence over a sensitive and delicate mind, and of which even the strongest and most sceptical mind must for a moment feel the spell. As I turned page after page, and gradually mastered the entire drift of the book, I asked myself could it be that all the terrors of the supernatural had been brought to bear upon Ora’s imagination, and that the fears which bound her were of this extraordinary nature?

‘You do not believe a word of all this terrible nonsense?’ I said, smiling as I closed the uncanny volume, which seemed to almost smell of brimstone.

She gazed at me with a look of amazement, in which there was for a second a gleam of something like relief.

‘Ah,’ she said, ‘you talk like that because you are ignorant. You are not so well educated as I am. See here!’

She drew back a curtain that covered some rows of bookshelves, all filled with volumes looking like fit companions of the book on the table.

‘Look over these,’ said Ora, ‘and you will see that my instruction has not been neglected.’

I did look through them, and found them the most extraordinary assemblage of compositions that were ever brought together for the bewilderment of human creatures. There were several long treatises on astrology, dream-like, mystical books full of fascination; then came augury, the knowledge of signs and omens; necromancy, witchcraft, and vividly detailed information regarding leagues with the person of Satan who powerfully underlays all the movements of the world.

‘If these and these only have been your school books,’ I reflected, ‘Heaven help you, poor Ora!’

I thought of a lonely childhood and youth passed in this wilderness of rock and ocean, of winters which were probably all one long, howling storm, and asked myself how the poor girl had preserved her senses, fed upon teaching such as this.

‘Are these books your father’s?’ I asked, hardly able to contain my indignation against the wretch who had so poisoned her mind.

‘Some of them,’ she answered with a quiver of the lip. ‘Those on astrology.’

‘And who gave you the others?’

She trembled, cast me the wild look she had given me on the mountain, and threw up her hands in a defensive attitude.

‘Don’t!’ she said hoarsely. ‘Don’t ask me questions. If I answer them I shall have to hate you for evermore.’

She then turned quickly towards the wall, and leaning against it, hid her face between her hands.

The words, the movement, gave me a thrill of gladness.

‘Ora,’ I said. ‘You must never hate me. Nay, listen to me. If you can love me instead, I will take you away out of this miserable life, with its secret dread of Heavens only knows what! As my wife you shall have every happiness that a loving heart can procure for you. And I shall ask you no questions. If ever a moment comes when you feel you can confide in me, dear, I shall trust that then you will speak.’

I drew away her hands from her face, and she looked at me with a bewildered blush of surprise.

‘You?’ she stammered. ‘You would marry me?’

‘Is that so very unreasonable?’

Her face became gradually glorified by a look of such radiant joy as showed for me an instant what happiness might make of her; but it faded quickly away: the joy went out like a light in a gust of wind, the blush was replaced by an ashen pallor.

‘Oh, why has this come to me,’ she murmured with quivering lips, ‘only to be found impossible, only to deepen my misery?’

‘Why impossible, Ora?’

‘That I cannot tell you. If I were to tell you it would bring such ruin as you could not bear to hurl upon me.’

Having said this, her old, reticent calm descended upon her like armour; she withdrew herself from me, went over to the table, and taking up the book she had been reading, replaced it on the shelf with its companions, drawing the curtain across, as if to prevent any return to the discussion of the subject of her studies. Then she stood silently waiting, as if expecting me to leave her.

‘You had better go to your room,’ she said gently. ‘He – he will be displeased if he finds you here with me.’

I obeyed her desire at once, fearing to bring down a tyrant’s wrath upon that tender head.

The room assigned to me was small, but its windows were well placed, being in the gable of the house, and thus commanding both a noble view of the inland, with its mountains, and the island-strewn sea. True, it was rather out of reach, and at an inconvenient height – so that an effort must be made if one wanted to enjoy the outside world through its medium. It would seem, indeed, as if the windows of this house had been planned with a view to shutting out the perpetual sight of the ocean that was so near. Had the builder foreseen that future dwellers within the walls might find the companionship of the great ocean momentously intolerable? Whether, or not, the blindness, so to speak, of the house, and the bold and peering inquisitiveness of the observatory close by, struck me as contrasting with each other curiously.

I extinguished my light and threw myself on the bed, but felt that I was not likely to sleep. My mind flew back over all the events of the day, and I could scarcely believe that I was the same person who had parted from his peasant-entertainer in the morning, saying: ‘I will take care to avoid old Collum’s dwelling.’ I felt as if years must have elapsed since the time when I had never seen Ora, since the moment when I saw her darting to meet me upon the mountain, as if the sun had cast her upon my path. Since I had beheld that light of love and joy in her face, I resolved that nothing would induce me to give up the hope of making her my wife– an impenetrable mystery should daunt me; no terror, natural or supernatural, should be allowed to wrench her away from me. At the same time, I must be careful not to persecute her. Ignorant as I was of the cause of her sorrow and fear, I must be content to wait patiently; if necessary, to watch over her from a distance. Time, which unveils wonders, would be certain to unravel the mystery in which Ora was entangled.

As the night advanced I became more and more fevered with tantalising thoughts and vain speculations; at last, faint indications of approaching dawn appeared, and I left my bed, and with some difficulty established myself in such a position at the window as enabled me to have a view of all the landscape beauties below. I looked down into a sheer bed of rocks, which went like jagged steps to the sea; and beyond this foreground lay the ocean, with its islands dimly discernible in the misty daybreak. One by one the darkness gave up its hidden treasures, and allowed them to creep under the mysterious grey veil of the morning.

‘The sun will come,’ I said to myself. ‘The sun will come; and presently how beautiful this all will be!’

I was trying to persuade myself that the clouds and mysteries of Ora’s life would dissolve away when a slight sound immediately below startled me, a sound no greater than the flutter of a bird’s wing, but sufficient in the intense stillness to make me look to see whence it proceeded. And I did look, and beheld a sight which surprised me: Ora gliding over the rocks like a spirit, stopping to look around anxiously, as if afraid of being observed, and then hurrying on towards the sea. A shawl was around her head and shoulders, and she carried a basket on her arm. She was clearly going on a journey, and was making towards the verge of the cliffs. Was it possible her household duties could take her away to a distance at this extraordinary hour? And where could she be going by water?

I lost sight of her for a few moments as she disappeared among the rocks, but soon a little boat shot out from beyond them, and Ora was in it, rowing away from the land with all her might. Outward, still outward, I saw her darting like an impatient bird over the calm sea in the still grey dawn. The wildest thoughts came into my mind. Was she running away frantically, trying to escape from all her troubles at once: from the mystery of her home, from my love, the discoveries it might impel me to make, from every difficulty that best her? And whither? Had she any plan; or did she in her ignorance hope vaguely that she might reach by chance some goal of safety, touch with her little hunted feet some shore of peace, where, unknown and unquestioned, she might loosen the chords of misery by forgetting her own identity?

Suddenly my crazy thoughts were rebuked, and I saw that she had a simple and definite purpose in her voyage. She was making for one of the islands out yonder that was creeping one by one out of the shadows of the night. It was that particular islet of gloomy and fantastic shape and expression on which yesterday the sun had refused to shine, and over which the birds had talked and wheeled in my dream. She neared it, touched it; I saw her moor the boat and vanish among the rocks of the island shore.

After an interval of half an hour she reappeared, and presently I saw her coming, small and scarcely visible as she and her skiff were in the distance, and looking, as she plied her oars, like some dark sea bird on the wing. Landing where she embarked, she returned among the rocks with swift glances of alarm cast on all sides, and sped like a frightened dove into the shadows of the house.

I mused over this secret expedition of Ora’s. Her evident fear of being seen, and the fact that she bore with her a well-filled basket, which she carried carefully, bringing back the same basket empty, forbade me to suppose that she could have gone to fetch any simple produce of the island for household purposes. Whose observation had she feared? Not mine, for she never once glanced towards my window. Had she waited till her father had left his observatory, and might be supposed to be asleep, before she stole forth on her solitary adventure? And if not, what was the purpose of her visit to the island? I felt assured that some human creature’s need had drawn her to the secret expedition; she was supplying sustenance to that creature unknown to and in defiance of her father. I did not guess these facts; I divined them at once; and the knowledge gave an added pang to my mind.

Who was this person lingering in the retreat upon that gloomy island? Why did he stay there? If it were a man who had thus secured the devotion of a woman like Ora, why did he not free himself and her? Why did he not step into her boat, and escape with her into the safety of the vastness of the world? I wearied myself with asking questions, with indulging my indignation against this cowardly protégé of Ora’s, who was content to lie by and let her suffer, till my reasoning powers returned, and I remembered that I knew nothing of the facts of the case.

On leaving my tiny apartment I found breakfast ready for me in the sitting-room, and Ora waited upon me as she had done the day before. She looked unnaturally pale, and there were dark circles round her eyes that told a tale of suffering. She was in her most impenetrable mood, and I scarcely ventured to speak to her. Whilst I was at breakfast old Collum came into the room, and though he kept up an appearance of civility in his manner towards me, yet I felt my hour had come, and that I must go. He had bestowed his society upon me in order that he might see me out of the house. There, in his presence, I was obliged to say goodbye to Ora, and left the place accompanied by the man, who walked with me a mile along the shore.

I arrived at Gurteen in the evening but found it impossible either to stay there or go further away from old Collum’s observatory. The knowledge of Ora’s lonely trouble held me like a chord, and the thought of that gloomy island, with Ora’s little boat speeding towards it, haunted me wherever I turned. The overwhelming desire to know more of the mystery I had left behind me so deprived me of the power of pursuing any other idea, so ignored all difficulties in the way of discovery, that I gave up battling with it, and resolved to spend the remaining time at my disposal in hovering near the spot which I had quitted in the morning. Having rested a few hours in the village inn, I set out again in the twilight to walk back the way I had come, without having any positive purpose in so doing, and drawn only by the craving to see whether Ora’s little boat would again be on the water in the still grey hours that lie between the night and the dawn.

At a certain distance from Ora’s home, I found a cave in the rocks in which I could rest, with my eyes on that line across the sea from the house by the observatory to the gloomy island. A faint moonlight illuminated the track as I began my watch; but it soon vanished with its shadows, and in the pale obscurity that followed, I saw the thing I expected to see – Ora’s small boat on its solitary voyage. She went and came as on the preceding night, and in the sunrise there came a vivid light across my mind. I remembered that when Ora met me on the mountain she had pointed towards the sea: she had indicated the very island which she now visited by night. I had felt that she was bringing me some message from the ocean, but afterwards I had forgotten this striking impression made by her gesture in the first moment of her appearance. Now the first and the last seemed to join and close the circle of my speculation: the beginning and end of Ora’s mystery was centred in the island.