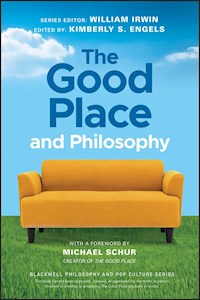

The Good Place and Philosophy E-Book

14,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Serie: The Blackwell Philosophy and Pop Culture Series

- Sprache: Englisch

Dive into the moral philosophy at the heart of all four seasons of NBC's The Good Place, guided by academic experts including the show's philosophical consultants Pamela Hieronymi and Todd May, and featuring a foreword from creator and showrunner Michael Schur * Explicitly dedicated to the philosophical concepts, questions, and fundamental ethical dilemmas at the heart of the thoughtful and ambitious NBC sitcom The Good Place * Navigates the murky waters of moral philosophy in more conceptual depth to call into question what Chidi's ethics lessons--and the show--get right about learning to be a good person * Features contributions from The Good Place's philosophical consultants, Pamela Hieronymi and Todd May, and introduced by the show's creator and showrunner Michael Schur (Parks and Recreation, The Office) * Engages classic philosophical questions, including the clash between utilitarianism and deontological ethics in the "Trolley Problem," Kant's categorical imperative, Sartre's nihilism, and T.M Scanlon's contractualism * Explores themes such as death, love, moral heroism, free will, responsibility, artificial intelligence, fatalism, skepticism, virtue ethics, perception, and the nature of autonomy in the surreal heaven-like afterlife of the Good Place * Led by Kimberly S. Engels, co-editor of Westworld and Philosophy

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 554

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright Page

Contributors

Editor’s Introduction and Acknowledgments

Foreword

Introduction:

Pamela Hieronymi and Todd May, philosophical advisors to The Good Place

Part I: “I JUST ETHICS’D YOU IN THE FACE”

1 How Do You Like Them Ethics?

What Makes an Action Right?

Should It Bother Us?

The Coincidence Thesis

Benevolent Administration

Tragedy, Comedy, or Cincinnati?

2 Don’t Let the Good Life Pass You By: Doug Forcett and the Limits of Self‐Sacrifice

“Michael, Face Facts. Doug Is Not the Blueprint of How to Live a Good Life. He’s Become a Happiness Pump.” —Janet

“We Are Here to Celebrate the Life of Martin Luther Gandhi Tyler Moore, the Snail.” —Doug

“I Should Donate More Blood. I’ll Try, but the Last Time I Went Down There, They Said I Was So Anemic They Ended Up Giving

Me

Blood.” —Doug

Snails and Radishes

“I Just Want to Be Virtuous for Virtue’s Sake.” —Eleanor

3 Luck and Fairness in The Good Place

Fairness and Judgment

Morality and Control

Moral Luck in

The Good Place

Unfairness in the System

Judgment and Ideals

The New System

Part II: “VIRTUOUS FOR VIRTUE'S SAKE”

4 Can Eleanor Really Become a Better Person?

Aristotle’s Guide to Moral Growth

Aristotle’s Four Levels of Moral Character

Kohlberg’s Model of Moral Development

Does Character Actually Matter?

The Moral of the Story

5 The Good Place and The Good Life

Being Happy and Being Good

Who Died and Left Aristotle in Charge of Ethics?

Why Kant We Be Good?

Utilitarianism: It’s So Simple!

We Are Not in This Alone

6 The Ethics of Indecision: Why Chidi Anagonye Belongs in The Bad Place

Aristotle’s Virtue Theory: Learning to Be Good

Decision Making 101: The Practical Syllogism

Practical Wisdom (

Phronesis

): “I Have to Consider All the Factors”

Can’t We Just Give Chidi a Break?!

A Medium Place for Medium People

Part III: “ALL THOSE ETHICS LESSONS PAID OFF”

7 Moral Absurdity and Care Ethics in The Good Place

Moral Absurdity

Good Enough for The Good Place

A Different Moral Calculus

The Remedy to Absurdity

8 The Medium Place: Third Space, Morality, and Being In Between

Escape, Neutrality, and Stomachache

Eleanor’s “Third Possibility”

Dialectics, Contradictions, and Mindy’s Weird Beige House

Self‐Exploration and Becoming

Third Space and Medium Morality

Don’t Let the Good Life Pass You By

We’re All Medium People!

9 What We May Learn from Michael’s Solution to the Trolley Problem

The Point of Human Ethics

Trolleys in

The Good Place

Sacrifice Yourself!

What Else the Massive Man Should Complain About

Michael’s Solution

Part IV: “HELP IS OTHER PEOPLE”

10 Some Memories You May Have Forgotten: Holding Space for Each Other When Memory Fails

Stories, Relationships, and the Moral Self in

The Good Place

Stories, Relationships, and the Moral Self in This Actual World

What Is Memory?

Constructing Memories of What Really Matters

The Ethics of Memory

Some Memories You May Have Forgotten

11 The Good Other

Old Habits Die Hard (Not as Hard as Those People You Crushed with the Trolley, Though)

I Want to Become the Person I Pretended to Be

Pobody’s Nerfect!

Conclusion: The Good Other

12 Not Knowing Your Place: A Tale of Two Women

“You’re Okay, Eleanor. You’re in The Good Place.”

“Take It Away from Me! Sorry, I Mean Take It Away, Kamilah.”

Irigaray and Woman as Other

“My Whole Life I’ve Tried to Be Extraordinary, but It Has Never Seemed to Be Enough.”

… Coming from a Place Where Penis Envy Is a Thing

Why Haven’t You Forkers Invented a Medium Place?

“Surprise Idiots! You’re All in The Bad Place.”

Part V: “ABSURDITY NEEDS TO BE CONFRONTED”

13 Marginal ComfortsKeep Us in Hell

Bad Faith and Bad Place

Everything Is Fine!

Chidi, the Serious Man

A Turn toward Authenticity and against Comfort

Welcome! Not Everything Is Fine!

14 “I Would Refuse to Be a God if It Were Offered to Me”: Architects and Existentialism in

The Good Place

The Silent Indifference of an Empty Universe

Existential Crisis

You’re All in The Bad Place

Snowplowing Circumstances

I Would Refuse to Be a God

Part VI: “SEARCHING FOR MEANING IS PHILOSOPHICAL SUICIDE”

15 Death, Meaning, and Existential Crises

“So You’re Saying That I Would Be …

No … Me

?”

“Searching for Meaning Is Philosophical Suicide”

“Let Me Just Get into the Mindset of a Human”

“I’m Gonna Eat All This Chili and/or Die Trying”

“I’m Gonna Teach You the Meaning of Life”

“Holy Crap! I Just Almost Died”

“We’re All Just Corpses Who Haven’t Yet Begun to Decay”

16 From Indecision to Ambiguity: Simone de Beauvoir and Chidi’s Moral Growth

Chidi’s Indecision as

Seriousness

Chidi’s Nihilistic Chili

Reboot: Chidi’s Positive Ambiguity

Pandemonium, or Not?

Getting to “The Answer”

17 Beyond Good and Evil Places: Eternal Return of the Superhuman

Aim for the Stars, for the Superhuman

Demons Too Can Go beyond Themselves

Eleanor Really Is Better than Others

The Problem of Getting to The Good Place

Me versus Us

The End of History?

Beyond Good and Evil Places

Part VII: “THE DALAI LAMA TEXTED ME THAT”

18 Conceptions of the Afterlife:

The Good Place

and Religious Tradition

Why Religion, and Which One?

Asian Religions and

The Good Place

Indian Philosophy, Hindu Religion, and

The Good Place

Meaning Making and Religious Pluralism

19 Who Are Chidi and Eleanor in a Past‐(After)Life? The Buddhist Notion of No‐Self

Would the “Real Chidi” Please Stand Up?

The Buddhist Critiques of the Self: What the “Fork” Is a “Chidi”?

Every “Thing” Changes

The Self as a Useful Fiction

Part VIII: “SOMETIMES A FLAW CAN MAKE SOMETHING EVEN MORE BEAUTIFUL”

20 Hell Is Other People’s Tastes

Eleanor’s Clown Nook

Tahani’s Mansion and Jason’s Bud‐Hole

No Good Place for Chidi

“Oh Cool, More Philosophy—That Will Help Us!”

The Metaphysics of Taste in The Good Place

Hell Is Other People’s Tastes

21 Why Everyone Hates Moral Philosophy Professors: The Aesthetics of Shallowness

Hell Is Ordinary People

Why Does Everyone Hate Moral Philosophers?

Philosophy and Depth

Depth and Existentialism

Chidi’s Tragic Flaw

My Love‐Hate Relationship with Professors of Ethics and Moral Philosophy

Conclusion: The Aesthetics of Shallowness

Part IX: “OH COOL, MORE PHILOSOPHY! THAT WILL HELP US.”

22 An Epistemological Nightmare? Ways of Knowing in

The Good Place

Three Types of Knowledge

The Requirements of Propositional Knowledge

Justification, Sources of Knowledge, and Chidi’s Nightmare

A Debate about Justification (and Janet)

“Here Comes the Egghead …”

23 What’s the Use of Free Will?

Free Will

The Case against Free Will

Determinism

Compatibilism

Michael’s 15‐Million‐Point Plan

When Is the Will Free?

In Defense of Free Will

The Use of Free Will

Moral Responsibility

Determinism versus Moral Responsibility

24 From Clickwheel through Busty Alexa: The Embodied Case for Janet as Artificial Intelligence

Embodiment Matters

Wisdom and Social Abilities

A Moral Neighborhood

Not Just a Janet Anymore

25 Why It Wouldn’t Be Rational to Believe You’re in The Good Place (and Why You Wouldn’t Want to Be There Anyway)

Cartesian Skepticism about The Good Place

The Good Place as a Good Explanation

Scientific Skepticism about The Good Place

Cosmic Coachella

Conclusion: The Meaning of Life

Index

End User License Agreement

Guide

Cover

Table of Contents

Begin Reading

Pages

ii

iii

iv

ix

x

xi

xii

xiii

xiv

xv

xvii

xviii

xix

xxi

xxii

xxiii

xxiv

xxv

xxvi

xxvii

1

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

35

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

153

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

172

173

174

175

176

177

178

179

180

181

182

183

184

185

186

187

188

189

191

192

193

194

195

196

197

198

199

200

201

202

203

204

205

206

207

208

209

211

213

214

215

216

217

218

219

220

221

222

223

224

225

226

227

228

229

230

231

232

233

234

235

237

239

240

241

242

243

244

245

246

247

248

249

250

251

252

253

254

255

256

257

258

259

260

261

262

263

264

265

266

267

268

269

270

271

272

273

274

275

276

277

278

279

280

281

282

283

284

285

286

287

The Blackwell Philosophy and Pop Culture Series

Series editor: William Irwin

A spoonful of sugar helps the medicine go down, and a healthy helping of popular culture clears the cobwebs from Kant. Philosophy has had a public relations problem for a few centuries now. This series aims to change that, showing that philosophy is relevant to your life—and not just for answering the big questions like “To be or not to be?” but for answering the little questions: “To watch or not to watch South Park?” Thinking deeply about TV, movies, and music doesn’t make you a “complete idiot.” In fact it might make you a philosopher, someone who believes the unexamined life is not worth living and the unexamined cartoon is not worth watching.

Already published in the series:

24 and Philosophy: The World According to JackEdited by Jennifer Hart Weed, Richard Brian Davis, and Ronald Weed

30 Rock and Philosophy: We Want to Go to ThereEdited by J. Jeremy Wisnewski

Alice in Wonderland and Philosophy: Curiouser and CuriouserEdited by Richard Brian Davis

Alien and Philosophy: I Infest, Therefore I AmEdited by Jeffery A. Ewing and Kevin S. Decker

Arrested Development and Philosophy: They’ve Made a Huge MistakeEdited by Kristopher G. Phillips and J. Jeremy Wisnewski

Avatar and Philosophy: Learning to SeeEdited by George A. Dunn

The Avengers and Philosophy: Earth’s Mightiest ThinkersEdited by Mark D. White

Batman and Philosophy: The Dark Knight of the SoulEdited by Mark D. White and Robert Arp

Battlestar Galactica and Philosophy: Knowledge Here Begins Out ThereEdited by Jason T. Eberl

The Big Bang Theory and Philosophy: Rock, Paper, Scissors, Aristotle, LockeEdited by Dean Kowalski

The Big Lebowski and Philosophy: Keeping Your Mind Limber with Abiding WisdomEdited by Peter S. Fosl

BioShock and Philosophy: Irrational Game, Rational BookEdited by Luke Cuddy

Black Mirror and PhilosophyEdited by David Kyle Johnson

Black Sabbath and Philosophy: Mastering RealityEdited by William Irwin

The Ultimate Daily Show and Philosophy: More Moments of Zen, More Indecision TheoryEdited by Jason Holt

Disney and Philosophy: Truth, Trust, and a Little Bit of Pixie DustEdited by Richard B. Davis

Doctor Strange and Philosophy: The Other Book of Forbidden KnowledgeEdited by Mark D. White

Downton Abbey and Philosophy: The Truth Is Neither Here Nor ThereEdited by Mark D. White

Dungeons and Dragons and Philosophy: Read and Gain Advantage on All Wisdom ChecksEdited by Christopher Robichaud

Ender’s Game and Philosophy: The Logic Gate is DownEdited by Kevin S. Decker

Family Guy and Philosophy: A Cure for the PetardedEdited by J. Jeremy Wisnewski

Final Fantasy and Philosophy: The Ultimate WalkthroughEdited by Jason P. Blahuta and Michel S. Beaulieu

Game of Thrones and Philosophy: Logic Cuts Deeper Than SwordsEdited by Henry Jacoby

The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo and Philosophy: Everything Is FireEdited by Eric Bronson

Green Lantern and Philosophy: No Evil Shall Escape this BookEdited by Jane Dryden and Mark D. White

The Ultimate Harry Potter and Philosophy: Hogwarts for MugglesEdited by Gregory Bassham

Heroes and Philosophy: Buy the Book, Save the WorldEdited by David Kyle Johnson

The Hobbit and Philosophy: For When You’ve Lost Your Dwarves, Your Wizard, and Your WayEdited by Gregory Bassham and Eric Bronson

House and Philosophy: Everybody LiesEdited by Henry Jacoby

House of Cards and Philosophy: Underwood’s RepublicEdited by J. Edward Hackett

The Hunger Games and Philosophy: A Critique of Pure TreasonEdited by George Dunn and Nicolas Michaud

Inception and Philosophy: Because It’s Never Just a DreamEdited by David Kyle Johnson

Iron Man and Philosophy: Facing the Stark RealityEdited by Mark D. White

LEGO and Philosophy: Constructing Reality Brick By BrickEdited by Roy T. Cook and Sondra Bacharach

The Ultimate Lost and Philosophy: Think Together, Die AloneEdited by Sharon Kaye

Mad Men and Philosophy: Nothing Is as It SeemsEdited by James South and Rod Carveth

Metallica and Philosophy: A Crash Course in Brain SurgeryEdited by William Irwin

The Office and Philosophy: Scenes from the Unfinished LifeEdited by J. Jeremy Wisnewski

Saturday Night Live and PhilosophyEdited by Ruth Tallman and Jason Southworth

Sons of Anarchy and Philosophy: Brains Before BulletsEdited by George A. Dunn and Jason T. Eberl

The Ultimate South Park and Philosophy: Respect My Philosophah!Edited by Robert Arp and Kevin S. Decker

Spider‐Man and Philosophy: The Web of InquiryEdited by Jonathan J. Sanford

The Ultimate Star Trek and Philosophy: The Search for SocratesEdited by Jason T. Eberl and Kevin S. Decker

The Ultimate Star Wars and Philosophy: You Must Unlearn What You Have LearnedEdited by Jason T. Eberl and Kevin S. Decker

Superman and Philosophy: What Would the Man of Steel Do?Edited by Mark D. White

Supernatural and Philosophy: Metaphysics and Monsters…for IdjitsEdited by Galen A. Foresman

Terminator and Philosophy: I’ll Be Back, Therefore I AmEdited by Richard Brown and Kevin S. Decker

True Blood and Philosophy: We Wanna Think Bad Things with YouEdited by George Dunn and Rebecca Housel

True Blood and Philosophy: We Wanna Think Bad Things with You, Expanded EditionEdited by George Dunn and Rebecca Housel

True Detective and Philosophy: A Deeper Kind of DarknessEdited by Jacob Graham and Tom Sparrow

Twilight and Philosophy: Vampires, Vegetarians, and the Pursuit of ImmortalityEdited by Rebecca Housel and J. Jeremy Wisnewski

Veronica Mars and Philosophy: Investigating the Mysteries of Life (Which is a Bitch Until You Die)Edited by George A. Dunn

The Walking Dead and Philosophy: Shotgun. Machete. Reason.Edited by Christopher Robichaud

Watchmen and Philosophy: A Rorschach TestEdited by Mark D. White

Westworld and Philosophy: If You Go Looking for the Truth, Get the Whole ThingEdited by James B. South and Kimberly S. Engels

Wonder Woman and Philosophy: The Amazonian MystiqueEdited by Jacob M. Held

X‐Men and Philosophy: Astonishing Insight and Uncanny Argument in the Mutant X‐VerseEdited by Rebecca Housel and J. Jeremy Wisnewski

THE GOOD PLACE AND PHILOSOPHY: EVERYTHING IS FORKING FINE!

Edited by

Kimberly S. Engels

This edition first published 2021© 2021 John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by law. Advice on how to obtain permission to reuse material from this title is available at http://www.wiley.com/go/permissions.

The right of Kimberly S. Engels to be identified as the author of the editorial material in this work has been asserted in accordance with law.

Registered OfficeJohn Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, USA

Editorial Office111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, USA

For details of our global editorial offices, customer services, and more information about Wiley products visit us at www.wiley.com.

Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats and by print‐on‐demand. Some content that appears in standard print versions of this book may not be available in other

Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of WarrantyWhile the publisher and authors have used their best efforts in preparing this work, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this work and specifically disclaim all warranties, including without limitation any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. No warranty may be created or extended by sales representatives, written sales materials or promotional statements for this work. The fact that an organization, website, or product is referred to in this work as a citation and/or potential source of further information does not mean that the publisher and authors endorse the information or services the organization, website, or product may provide or recommendations it may make. This work is sold with the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering professional services. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for your situation. You should consult with a specialist where appropriate. Further, readers should be aware that websites listed in this work may have changed or disappeared between when this work was written and when it is read. Neither the publisher nor authors shall be liable for any loss of profit or any other commercial damages, including but not limited to special, incidental, consequential, or other damages.

Library of Congress Cataloging‐in‐Publication data applied for

9781119633280 (paperback)9781119633020 (adobe pdf)9781119633297 (epub)

Cover Design: WileyCover Images: Sky: © spooh/Getty ImagesSofa: © Pitinan Piyavatin/EyeEm/Getty ImagesGrass: © hadynyah/Getty Images

Contributors

Leslie A. Aarons is a Professor of Philosophy at City University of New York. Her specializations are in environmental and public philosophy. She has published numerous chapters in the Philosophy and Popular Culture series, including House of Cards and Philosophy: Underwood’s Republic (Wiley‐Blackwell); Philosophy and Breaking Bad (Palgrave Macmillan); and WikiLeaking: The Ethics of Secrecy and Exposure (Open Court). As an amateur chef she is proud of her latest signature dish that captures the delectable “Full Cellphone Battery” flavor in a perfectly executed chicken piccata.

David Baggett is Professor of Philosophy at Houston Baptist University and works in ethics, philosophy of religion, and natural theology. He’s the executive editor of MoralApologetics.com, and his most recent book is The Moral Argument: A History, co‐written with Jerry Walls. Unapologetic about drinking almond milk, he remains just 520,000,008 points shy of The Good Place.

Marybeth Baggett, an English Professor (not a philosopher) at Houston Baptist University, studies contemporary American literature, science fiction, and the life and work of groundbreaking artist and popular icon Kamilah. The Eleanor to David’s Chidi, Marybeth has authored two books and has been working for 18 years on her magnum opus, Why Do Bad Things Happen to Mediocre People Who Lie about Their Identity?

Steven A. Benko is a Professor of Religious and Ethical Studies at Meredith College. His research focuses on ethics, subjectivity, and culture. He is the co‐editor of The Good Place and Philosophy: Get an Afterlife, Ethics and Comedy (forthcoming) and has published articles on authenticity and The Good Place, religious humor in Monty Python’s Life of Brian, critical thinking pedagogy, and posthumanism. He once asked Chidi for help with an ethics syllabus, but Chidi said that it gave him a stomachache.

Kiki Berk is an Associate Professor of Philosophy at Southern New Hampshire University and currently holds the Papoutsy Chair in Ethics and Social Responsibility. She received her PhD in Philosophy from the VU University Amsterdam in 2010. Her current research interests include value theory (especially happiness), analytic existentialism (especially the meaning of life), and the philosophy of death. If searching for meaning is philosophical suicide, then her days are numbered.

Andreas Bruns is a PhD candidate at the University of Leeds. His research focuses on deontological ethics and moral conflicts. He teaches moral and political philosophy, and medical ethics. The Accounting Department assigns a negative value of −143 points to doing a PhD in philosophy, and the job prospects are terrible. But, as his good friend Barack once told him during a skiing holiday with Michelle and the kids, “You are not here to fear the future. You’re here to shape it. And where you are met with cynicism and doubts and those who tell you that you can’t, tell them: Yes, I can.”

Andrew Davison is a student at the Gatton Academy of Mathematics and Science, so you may be surprised to see him listed as a contributor to a philosophy volume. He researches applications of the Fourier Transform and other mathy stuff. This is his first philosophy chapter and his second publication. Clearly, Andrew is conflicted about what exactly he wants to do when he “grows up,” but hopefully he can be as cool as his dad (see: Scott Davison). As Jason Mendoza once said, “I’m just trying to figure out what the fork is happening.”

Scott A. Davison is Professor of Philosophy at Morehead State University. He is the author of two books, On the Intrinsic Value of Everything (Continuum, 2012) and Petitionary Prayer: A Philosophical Investigation (Oxford, 2017), and a number of articles in the areas of metaphysics, philosophy of religion, and value theory. He serves as the book review editor for the International Journal for Philosophy of Religion and the associate editor of the journal Faith and Philosophy. In his spare time, he likes to build things and hang out with his children and his rabbits. Other than that, as Eleanor has told him repeatedly, “Ya basic.”

Kimberly S. Engels is Assistant Professor of Philosophy at Molloy College. Her research focuses on existentialism as a contemporary living philosophy, applicable to all domains of modern life. She is co‐editor of the book Westworld and Philosophy: If You Go Looking for the Truth, Get the Whole Thing (Wiley‐Blackwell, 2018), and has published articles relating existentialism to issues in environmental ethics, medical ethics, and public policy. Jason Mendoza once told her, “You’ve got a dope soul and hella ethics.”

T Storm Heter teaches Philosophy at East Stroudsburg University. He is author of Sartre’s Ethics of Engagement (Continuum, 2006) and he writes about existentialism, music, and critical race theory.

Darren Hudson Hick is the author of Introducing Aesthetics and the Philosophy of Art (2017) and Artistic License: The Philosophical Problems of Copyright & Appropriation (2017), and co‐editor of The Aesthetics and Ethics of Copying (2016). Unbeknownst to Sarah Worth, his bud‐hole is mostly filled with velvet Elvis paintings.

Pamela Hieronymi is a Professor of Philosophy at UCLA. She has published on moral responsibility and on our control over our own states of mind. She is currently bringing these two strands together into a book, Minds That Matter, in order to unwind the traditional problem of free will. She and Chidi are still trying to decide which quotation to use for this bio.

Jake Jackson is a PhD Candidate in Philosophy at Temple University writing on depression, anxiety, and moral responsibility. His published work examines how to navigate depression and anxiety within a stigmatizing world. He’s been compared to Chidi a few too many times and tries his best to ignore his point totals, but fears the Time Knife.

David Kyle Johnson is a Professor of Philosophy at King’s College in Wilkes‐Barre, Pennsylvania, who also produces lecture series for The Teaching Company’s The Great Courses. His specializations include metaphysics, logic, and philosophy of religion, and his “Great Courses” include Sci‐Phi: Science Fiction as Philosophy, The Big Questions of Philosophy, and Exploring Metaphysics. Kyle is the editor‐in‐chief of The Palgrave Handbook of Popular Culture as Philosophy (forthcoming), and has also edited other volumes for Wiley‐Blackwell, including Black Mirror and Philosophy: Dark Reflections and Inception and Philosophy: Because It’s Never Just a Dream. Thanks to Lisa Kudrow, his six‐year‐old son Johney won’t stop calling him a think‐read‐book‐man.

Dean A. Kowalski is a Professor of Philosophy and Chair of the Arts & Humanities Department in the College of General Studies at the University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee. He regularly teaches philosophy of religion, Asian philosophy, and ethics. He is the author of Joss Whedon as Philosopher (2017), Classic Questions and Contemporary Film, 2nd edition (2016), and Moral Theory at the Movies (2012). He is the editor of The Big Bang Theory and Philosophy (2012), The Philosophy of The X‐Files, revised edition (2009), and Steven Spielberg and Philosophy (2008); he is the coeditor of The Philosophy of Joss Whedon (2011). Like Chidi, he is vexed by what you might call directional insanity. Vexed. Just ask his wife (or any of his friends, really).

Being a fairly young soul, this is only James Lawler’s 322nd time for participating in The Good Place and Philosophy. Previously, some may recall, during his 321st time round his classic book The God Tube: Uncovering the Hidden Spiritual Message in Pop Culture (Open Court, 2010) won the Noble [sic] Prize, beating out Bob Dillon [sic] that year. Dillon (this time around he spells it Dylan) failed then to convince the jury with his song “The Times Are They Are Unchangin’.” After 702 repetitions, he finally got the message, showing that humanity is indeed making progress. James is still at the State University of New York at Buffalo, but this time, for those who remember, in the Philosophy Department, not Astrophysics.

If Greg Littmann goes to The Good Place, he’ll still get to be an Associate Professor of Philosophy at Southern Illinois University Edwardsville. But the exams will all magically grade themselves. He’ll still publish in metaphysics, epistemology, philosophy of logic, and the philosophy of professional philosophy. He’ll still write chapters relating philosophy to popular culture, like the ones he’s written for books devoted to Big Bang Theory, Black Mirror, Doctor Who, Game of Thrones, It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia, The Walking Dead, and others. But there’ll be no word limits or due dates, and his word processor will automatically underline bad ideas in red. If Greg goes to The Bad Place, the students will ask, “Will this be on the exam?” anytime he says anything in class. He’ll still be allowed to write, but Plato and Aristotle will stand over his shoulder, sniggering.

Laura Matthews is an Instructor in the Department of Philosophy at Auburn University. Her research focuses on integrating phenomenology with 4E (embodied, embedded, enactive, and extended) approaches to cognition. She is particularly interested in the application of these approaches to philosophical problems surrounding the classification and treatment of mental illness. She is currently finishing her thesis on an enactive approach to mental illness at the University of Georgia. Chidi once sat in on one of Laura’s lectures and complimented her that it was “so bleak.”

Todd May is Class of 1941 Memorial Professor of the Humanities at Clemson University. He is the author of sixteen books of philosophy, most recently A Decent Life: Morality for the Rest of Us and Kenneth Lonergan: Filmmaker and Philosopher. When Jason tells Shawn, “You used to be cool. But you’ve changed, man,” he was thinking of Todd. Except the cool part.

Michael McGowan is Professor of Philosophy and Religion at Florida Southwestern State College. He is co‐editor of David Foster Wallace and Religion: Essays on Faith and Fiction (Bloomsbury Academic Press, 2019) and author of The Bridge: Revelation and Its Implications (Pickwick, 2015). He is currently interested in meaning‐of‐life questions and nihilism, or maybe he isn’t. Whatever.

Matthew P. Meyer is Assistant Professor of Philosophy at the University of Wisconsin–Eau Claire. His main areas of study are existentialism, phenomenology, and psychoanalysis. He has written a book entitled Archery and the Human Condition in Lacan, the Greeks, and Nietzsche: The Bow with the Greatest Tension (Lexington, 2019) and has published articles and chapters on Nietzsche and film, and in several Blackwell Philosophy and Pop Culture series books, on Sartre (and The Office), Nietzsche (and House of Cards), and aesthetics (and Westworld). Chidi Anogonye once gave him the answer to life, but he is not willing to share it.

Traci Phillipson is Visiting Assistant Professor of Philosophy at Marquette University. Her research focuses on Medieval Latin and Arabic philosophy and its Aristotelian roots. She works primarily on issues of will and intellect in Aquinas and Averroes. She, like Michael, thinks that human beings can be “g‐g‐good, sometimes.”

Alison Reiheld is Associate Professor of Philosophy at Southern Illinois University–Edwardsville. She is a regular contributor to the scholarly bioethics blog, IJFAB Blog, and hopes that her work there helps folks to think through tricky issues in medical ethics. In addition to her research on the ethics of memory, Dr. Reiheld deals with how power and social norms operate within social institutions to render some people and groups vulnerable in unethical ways. She tends to make folks question ethical conclusions that had at first seemed obvious. This is why everybody hates moral philosophers.

Catherine M. Robb is an Assistant Professor of Philosophy at Tilburg University in the Netherlands. At the moment she is interested in questions about the ethics and politics of self‐development, and also writes on the aesthetics of music. In her spare time she “takes it sleazy” just like Eleanor, although she prefers red wine to margaritas.

Dane Sawyer is Senior Adjunct Professor of Philosophy and Religion at the University of La Verne. His research focuses on the interconnections among existentialism, philosophy of mind, Buddhism, and meditation. Tahani often brags that Dane offered her “exquisite” and “unsurpassable” meditation advice and philosophical reflections on the nature of mind during her time as a Tibetan Buddhist monk.

Michael Schur is the creator of The Good Place. He also co‐created Brooklyn 99 and Parks and Recreation.

C. Scott Sevier is Professor of Philosophy at The College of Southern Nevada in Las Vegas. His research focuses on medieval philosophy and aesthetics as well as the nature of beauty. He is interested in the history of ideas and in philosophy as a wisdom tradition. He contributed a chapter to Psych and Philosophy: Some Dark Juju‐Magumbo (Open Court, 2013), and published articles relating to the aesthetics and morality of Aquinas, as well as the book Aquinas on Beauty (Lexington Press, 2015). If it seems like he talks too fast, it’s because he still goes to Andy’s Coffee, and he’s got a full punch‐card, Bro.

Eric J. Silverman is Associate Professor of Philosophy at Christopher Newport University, United States. He has twenty publications on topics in ethics, philosophy of religion, and medieval philosophy. His publications include two monographs, The Prudence of Love: How Possessing the Virtue of Love Benefits the Lover and The Supremacy of Love: An Agape‐Centered Vision of Aristotelian Virtue Ethics, and a co‐edited collection, Paradise Understood: New Philosophical Essays about Heaven. Although he shares much of Chidi’s fashion sense, it has never taken him more than fifteen minutes to choose a fedora.

Zachary Swanson is in his final year as an undergraduate at Christopher Newport University. He is applying to graduate programs in psychology. He is still in the process of completing his 4000‐page manuscript on the simple question: Why? Like Chidi, his brain makes noises as a fork in a garbage disposal.

Joshua Tepley is an Associate Professor of Philosophy at Saint Anselm College. He received his BA in philosophy from Bucknell University and his PhD in philosophy from the University of Notre Dame. His research focuses on the intersection between twentieth‐century continental philosophy and analytic metaphysics. The thing he looks forward to the most when he gets to The Good Place is hanging out with Judge Gen.

Sarah E. Worth is a professor at Furman University. She writes at the intersection of aesthetics and epistemology. She published In Defense of Reading in 2017 and is now working on a book called The Pleasures of Eating: A Philosophy of Taste. Sarah teaches classes about food and eating as often as she can, and believes, ironically, that although hell is other people’s tastes, frozen yogurt is pure heaven. She shares an office with Darren Hudson Hick that is decorated only with clown paintings.

Robin L. Zebrowski is Associate Professor of Cognitive Science at Beloit College. Her research focuses on artificial intelligence and human/computer interfaces, with a focus on the relationship between embodiment and conceptualization. Jason Mendoza thinks she’s the Pam Anderson boob motorcycle of people, but she also once got lost on an escalator.

Editor’s Introduction and Acknowledgments

Kimberly S. Engels

“We Are Not in This Alone”

So, why do it then? Why choose to be good, every day, if there is no guaranteed reward we can count on, now or in the afterlife? I argue that we choose to be good because of our bonds with other people and our innate desire to treat them with dignity. Simply put, we are not in this alone.

When Chidi Anagonye reads this aloud in “Somewhere Else,” he expresses the heart and soul of a show that succeeded in making philosophy both funny and mainstream. More than any work of contemporary pop culture, The Good Place explicitly explores the work of a variety of famous philosophers, yet it is anchored in one theme. As the show’s creator, Michael Schur, said in a 2018 plenary session of the annual meeting of the North American Sartre Society, “The goal is to try to ask the question what it means to be a good person. That was the one line source of the show.”

Despite Chidi’s desire for the first three and a half seasons, perhaps there is no single philosophical answer to that question. There is, though, a narrative answer. Through the story it tells, The Good Place shows us that being a good person is social. It involves becoming better together through our relationships and bonds with other people—through our shared experiences, sacrifices, triumphs, and failures. Simply put, we are not in this alone. This is true not just for Chidi but for all of us.

Indeed, I have not been alone at any stage with this book, which has its origins in a meeting of the North American Sartre Society (NASS) in November 2018 at the University of Mary Washington. The NASS includes many supportive, collaborative, and remarkable individuals who are even better when together. Each year’s meeting is filled with meaningful scholarship and companionship, but the 2018 gathering was extra special. The show’s creator, Michael Schur, and one of the show’s philosophical advisors, Todd May, joined us for a special plenary session about The Good Place and Sartre’s work. It was one of the most rewarding experiences of my professional life.

My gratitude to all who organized and participated in the event—Michael Schur, Todd May, Jake Jackson, Kiki Berk, and Craig Vasey—cannot be overstated. NASS president T Storm Heter, conference organizer Craig Vasey, as well as other members of the NASS executive committee then entrusted me to carry this project to the next stages. Michael Schur graciously agreed to write the foreword for the book. He was kind, responsive, and generous with his time. Likewise, the philosophical advisors for The Good Place, Todd May and Pamela Hieronymi, graciously agreed to write an introduction for the volume.

William Irwin, the Blackwell Philosophy and Pop Culture Series editor, helped turn the project into a reality. He offered invaluable assistance in every stage of the process. The contributing authors worked diligently, met important deadlines, and helped create something wonderful. Did I mention that I was not in this alone?

Last but not least, my daughter, Moriah A. Khan, binge‐watched the show with me on repeat. At this point she is a mega‐fan as well as a budding philosopher.

Foreword

In the summer of 2015, I found myself sitting in heavy traffic on a freeway in Los Angeles. Sitting in heavy traffic is one of our favorite pastimes out here, along with sitting in moderate traffic, inching along in light traffic, and canceling plans because there’s too much traffic. On this particular day, a man in a white sports car decided the rules of society didn’t apply to him—he is special! He has a white sports car!—and he pulled into the breakdown lane and sped by all of us poor suckers who were foolish enough to abide by a social contract.

“That guy,” I thought to myself, “just lost twenty points.”

It was a game I played sometimes—a little soul‐soother: I imagined that someone (or ‐thing) is omnisciently tallying up our moral triumphs and failures, filing them away for review in toto when our threads finally get snipped. I’m hardly the first person to imagine such a system, but in my version it was a real numbers game—a cold, computational, Moneyball‐style analysis of our every action. This time, when I played my little accounting game, something else occurred to me: if this were the actual grand, eternal system, whose computational rules would we be using? Would all moral philosophers even agree that white sports car man had lost a few points in that moment? Would there be a consensus as to how many points his act had cost him? Would their reasons for believing so be the same? And then I had one more (slightly less lofty) thought: is there any way this is a television show?

In the months that followed I conceived of and wrote the pilot for The Good Place, a comedy on NBC that I’ve now run for the last four years. The basic premise, if you haven’t seen it—though, if you haven’t, why the hell are you reading this book?—is this: Eleanor Shellstrop wakes up in the afterlife, and is told that she is in The Good Place. Though it’s explicitly nondenominational, The Good Place is a version of the Christian “heaven,” full of everything she’d ever want, and reserved (she’s told) for the very best people who ever lived. Humans’ moral scores have been scrupulously kept, points added and subtracted for every action, great and small, and only the real cream of the moral crop get into this paradise. The problem is: she is decidedly not the cream of the crop. She is a very mediocre person, who certainly does not qualify for this VIP Club of ethical superstars. There’s been a mistake.

Then a million other things happen, that would take too long to explain. Just watch the show, it’ll be easier. (And also, again, if you don’t know what happens in the show, why did you buy this book?)

In order to write the show the way it needed to be written—meaning, “not ignorantly”—I embarked on a self‐designed course of study into moral philosophy, a subject about which I knew very little. From my few courses in college, I remembered that Kant was strict, Mill was results‐oriented, and Socrates was forced to drink hemlock because he annoyed everyone in Athens until they couldn’t take it anymore. That was about it.

I bought a few survey books covering the basics—virtue ethics, utilitarianism, deontology—designed to lay down a primer coat of knowledge: Ethics for Dummies Who Write TV Shows. The problem was, every book and article pointed me to five others, which led me to twenty others after that. I bought more and more volumes, spent more and more time reading, got deeper and deeper into the philosophical weeds. My eyes were never unstrained. My Amazon cart was never empty.

It was exhausting—but it was fun. Oh man, was it fun. It didn’t feel like work, really—it felt like listening to a conversation, a 2500‐year‐long conversation these men and (far too late in the game) women were having with each other. The debates, and refutations, and criticisms.… Scanlon was talking to Rawls, who’d been talking to Kant, who’d been sniffing at Aristotle. Philippa Foot was talking to Mill, and then John Taurek snapped at the people who’d talked to her. The ideas were fascinating, but the conversation was the fun part. And as long as humans walk the planet, it occurred to me, it would never end. As T.M. Scanlon wrote, when concluding his magnum opus: working out the terms of moral justification is an unending task.

Which is why this volume delights me so much. When you start a TV show, you have very pedestrian goals: make something good, that entertains people. If you’re lucky, you make something audiences care about, and invest in, emotionally and intellectually. But this show had another, clandestine goal: to add to the conversation. I hoped the show could toss out a few ideas, ask a couple questions, raise a hand from the back of the class. An entire book full of ideas based on its contents was something I never dreamed of.

I’m very grateful to the academics who contributed to the pages within—and to the writers, actors, editors, and crew members who made the show sturdy enough in its scholarship to warrant those pages. I’m doubly grateful for everyone who watched the show and felt it contributed, in some small way, to the conversation of philosophy.

Michael SchurCreator of The Good Place

October 2019

Introduction: Pamela Hieronymi and Todd May, philosophical advisors to The Good Place

The philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein once remarked that “A serious and good philosophical work could be written consisting entirely of jokes.”1 But who, really, has tried this? Who would have the chutzpah, not to mention the fortitude, to write such a book? And if such a task were beyond most philosophers, what about this: a television show of philosophy composed largely of jokes?

If you’re reading these pages you already know that it’s been done. Tacking between the Scylla of cheapening philosophy and the Charybdis of unfunny humor (the dreaded philosophy jokes), The Good Place has sought to engage philosophy seriously while at the same time remaining an entertaining sitcom broadcast on network television. In particular, it has focused on the questions of how to be good and how to learn to be good in a world fraught with ethical complexities. Although the show engages in any number of philosophical arenas, for instance existentialism and the problem of personal identity, it always returns to the core issue of living an ethically decent life in a world that has the unfortunate tendency to push back.

In doing so, the show does not cleave to one or another of the ethical theories current in philosophical discussion. It presents Kant’s view, through the behavior of the academic philosopher Chidi, as a blind set of imperatives whose key is hard to discover and even harder to act upon. Consequentialism, on the other hand, comes in for critique in the form of the point system for getting into The Good Place. Consequences are impossible to calculate in a world where good and bad are so deeply entwined that even the most diligent of consequentialists—and who is more diligent than Doug Forcett?—cannot pull off the trick of earning enough points to achieve proper Good Place standing. As Judge Gen discovers when she takes her short foray to the land of the living, acting rightly, if we base it on consequences, is far too complicated to master.

In the first and second season, T.M. Scanlon’s What We Owe to Each Other looms large. Contractualism offers a contrast to both points and imperatives, with its update of the Golden Rule and its focus on respect and concern for other people. It is not so much the particularities of Scanlon’s theory that inform the show in its early episodes—although Chidi does present Scanlon’s idea that we should act on principles that others could not reasonably refuse—but rather the primary role that the theory gives to interpersonal relationships. In the first season, it is revealed that, in life, Eleanor never felt comfortable being part of any group; she was a distrustful loner (“Someone Like Me as a Member”). She turns a corner, though, when she convinces Jason and Janet that they all must return to The Good Place and sacrifice themselves, so that Chidi and Tahani are not sent to The Bad Place (“Mindy St. Claire”). Eleanor’s first motive is friendship, but its connection to justice comes through.

If there is a philosophical view that comes closest to what The Good Place puts before us, it would be Aristotle’s virtue ethics. And yet there is no wise person, no sage that stands as a model for those seekers of ethical living. Instead, all Eleanor, Chidi, Jason, Tahani, and Michael have are one another—flawed human beings (and a flawed immortal). What allows them to improve? What keeps them on the path even as, in the third season, they are convinced it will be impossible for any of them to enter The Good Place? In interview after interview about the show, Mike Schur returns to a single word: trying. Through their relationships with one another, they come to desire and then to try their hardest to become better people.

Trying, though, has its own hazards. Eleanor needs to try because she lacks the motivations of a good person. Aristotle would recommend that she do what the good person does, as a way to become a good person: in contemporary terms, “Fake it ’til you make it.” But sheer effort alone will not transform poor motives—motives are not like muscles; mere repetition will not effect change. To become a better person, your motives must be transformed, and effort alone does not guarantee transformation. In the pilot, Eleanor volunteered to pick up trash as a way of becoming better. She tried, but she couldn’t stick to it. Later, though, when she realized Chidi’s disappointment in missing his real soul mate, she was moved to kindness, without effort (and the sinkhole closed). Eleanor’s resolve again flags when she is back on earth, attempting to improve herself, but it revives when she hears Chidi’s lecture on contractualism, with its emphasis on interpersonal relations. As the humans (re)unite on earth and form friendships, their transformations begin.

Aristotle’s ethics is not, in the end, in tension with Scanlon’s contractualism. Aristotle recognized that becoming good is not something that one does on one’s own. Ethics, for him, is a part of politics: becoming good requires other people. The Good Place turns the Sartrean dictum that hell is other people on its head. Michael tries to create an interpersonal hell for Eleanor and the others, but it backfires. The four humans bond in bringing themselves to be better than they were. They recognize one another as people who are also seeking to live their lives as best they can, and they realize that they might do much worse than to try to help one another out.

As The Good Place’s characters learn this, we learn something important about them. It is a lesson that we would do well to heed in this period of profound polarization and mistrust. There is often more to people than our quick summary judgment of them leads us to believe. Eleanor, the “dirt bag from Arizona,” becomes, through her moral education alongside others, the most morally courageous of the group. There is nothing in the early episodes of the series that would make us predict this. Yet her evolution that stems from her relationships with others, especially but not exclusively Chidi, is entirely believable. There is more to her, and more to most people, than our snap judgments would tempt us to think. We can each be better—or at least try to be better—than we currently are; and, relatedly, we should realize that others are often better—or at least might well be better—than we think they are.

The essays in this volume approach The Good Place from a variety of philosophical angles, although ethics is never far from the text. The contributing authors engage in conversation with the thinkers one might expect—Sartre, Camus, Nietzsche, Aristotle, and Scanlon among them—developing their ideas in order to bring forward aspects or implications of the show that are either implicit or cannot be treated at length philosophically in the episodes themselves. (Let’s not forget that The Good Place is a sitcom, complete with fart jokes.) Although we cannot canvass those aspects and implications here—after all, that is the job of the essays themselves—perhaps a few quick gestures can indicate the rich resources of the show itself for philosophical reflection.

The final episode of the first season, “Michael’s Gambit,” calls to mind the quote from Sartre’s No Exit that “Hell is other people.” As several essays argue, and as is evident from the show itself, things are more complicated than those four words might, on their own, lead one to believe. To be sure, Michael designed The Good Place neighborhood with that very idea in mind. The frustration Chidi experiences in trying to teach Eleanor to be good (and the conflict he experiences, in keeping her secret), the exasperation Tahani feels in being unable to engage Jason in conversation, and so on lead to feelings of helplessness and self‐torture among the four characters. Nevertheless, as the show develops we become witness to an alternative: just as they can make one another miserable, so they can encourage one another to be better. If hell is other people, might it not be that heaven is as well?

This theme leads to another one: that of moral development. Several of the essays note the journey of moral development and self‐understanding that takes place. Eleanor, especially, comes to listen to the little voice in her head that warned her when she was about to do something wrong, a voice that she admits to Michael has always been there but that she had not been willing to pay attention to before. Likewise, Tahani comes to recognize that her feelings toward her sister have been one‐sided, and that her sister has had struggles with her parents’ expectations complementary to Tahani’s own. Being with one another over the course of The Good Place’s episodes has fostered these recognitions, and so the characters provide one another opportunities to become better persons, instead of just torturing one another.

Another theme that appears in the essays, and looms large in the show itself, is that of reward and punishment. In the third season we learn that nobody has gotten into the real Good Place in 521 years. This is because, as Judge Gen discovers, there are so many unforeseeable consequences of our behavior; it seems impossible to try to be good without thereby causing bad. This raises a question—and it is a question not only for moral reflection, but also for such social institutions as the contemporary prison: how should we think about the ways in which we judge one another? Challenging a simple calculus of good and bad consequences, the show asks us to consider the complexity of our fellow human beings. In a period in which polarization has lent itself to the formation of simple binaries in our assessments of others, the sitcom asks for nuance and grace.

Finally, a fourth theme, one that plays an important but sometimes implicit role in the show, is that of our freedom of action, particularly in the contemporary world. If the characters of the show are to be capable of moral development, then they must have the freedom to be able to engage in that development. However, their freedom of action is hedged by the complexity of our world, one in which to buy a rose for a loved one might contribute to exploitation (of the workers who picked the rose), climate change (through the transportation of the rose), and deforestation (if the rose was an element of a farm that cleared forest land in order to create a rose farm that will itself be laid waste). Although the general theme of free will and determinism only appears once in the show during a conversation between Michael and Eleanor (“The Worst Possible Use of Free Will”), the pressing question of our freedom to be good in a world fraught with unforeseen consequences is an abiding concern throughout.

In all, The Good Place offers much food for thought without either spoon‐feeding us or, as Wittgenstein worried about, unduly restricting our diet. By raising issues but refusing simple answers, by illustrating theories and dilemmas in ways that are at once provocative and entertaining, by allowing us to follow the moral development of four flawed individuals (and one flawed demon) through four seasons, the show displays how the reflective work of philosophy can be deep, engaging, and humorous all at once. And it has accomplished the trick that has eluded many of us in the field over these past several thousand years: it makes philosophy cool.

Note

1

Quoted in “A View from the Asylum” in Henry Dribble,

Philosophical Investigations from the Sanctity of the Press

(New York: iUniverse, 2004), 87.

Part I“I JUST ETHICS’D YOU IN THE FACE”

1How Do You Like Them Ethics?

David Baggett and Marybeth Baggett

As NBC’s breakout sitcom opens, Eleanor Shellstrop finds herself in a dilemma. She has died, and a cosmic mismanagement lands her in The Good Place, a secular version of heaven, completely by mistake. Confessing the error will almost certainly mean her removal to The Bad Place and eternal torture. So what should she do? It is out of this predicament that all the series’ hijinks ensue. In considering this tension, we find that two organically connected questions lie behind this delightful show: (1) whether morality requires that we do good for goodness’ sake and (2) whether reality itself is committed to morality.

Starring Ted Danson as the demon Michael and Kristen Bell as Eleanor—sweet, teentsy, and no freakin’ Gandhi—the show blazes a trail of brilliant fun from Nature’s Lasik to “Ya Basic!” As proof that moral philosophy professors aren’t as bad as the show’s running gag suggests, consider ethicist Chidi Anagonye’s Hamilton‐style rap musical: “My name is Kierkegaard and my writing is impeccable! / Check out my teleological suspension of the ethical!” Or how one day in class Eleanor dismissively asks, “Who died and left Aristotle in charge of ethics?” to which an exasperated Chidi replies, “Plato!”

Although the show is a comedy, the picture that emerges is one of tragedy, tragicomedy at best. Nobody, it turns out at the close of Season 3, has made it into The Good Place for centuries. Not even Doug Forcett is likely to make the cut, even though he’s the show’s quasi‐prophet who accidentally stumbled on the secret of the afterlife and has arguably led a faultless life ever since. The reason for this regrettable situation is life’s complexity. Even good‐intentioned behavior often results in a number of unintended bad consequences, yielding a net loss of “points” rather than a gain. The relative importance of intentions versus consequences is one of the vital philosophical questions the show raises. After discussing what the show has to say on the matter, we will offer our own view and why, if we’re right, the context of The Good Place, it turns out, is much more tragic than comic. Then we will consider the evidence of morality itself to see if it might suggest a different outcome. But enough of this bullshirt. It’s high time to take a swig from a putrid, disgusting bowl of ethical soup.

What Makes an Action Right?

Before reviewing how philosophers have answered the intentions/consequences question, let’s first consider the question itself. Some might say that actions are neither right nor wrong. The whole enterprise of morality, they suggest, is misguided. Perhaps life is meaningless or the category of morality is confused. A committed nihilist might insist there’s good reason to think there’s ultimately nothing to this morality business at all. There are simply no moral truths to be found.

This isn’t quite the position of Mindy St. Claire when she counsels Eleanor and company not to mess with ethics (“Mindy St. Claire”). Instead, she advises them to look out for number one. In principle that leaves open the possibility that she believes in objective morality and that we can know what such morality tells us to do, but that she is simply indifferent to it. Perhaps she sees morality and self‐interest as so much at odds that she simply gave up on what morality had to say. As she sees it, the more reliable path to happiness concerns promoting what’s best for oneself. Interestingly, the moral theory of ethical egoism says that doing what’s in one’s own ultimate best interest is our moral obligation. This is one way of maintaining a vital connection between what morality says and what’s best for us. There’s no particular evidence to suggest that Mindy held such an ethical account. What we know is simply that her life was about “making money and doing cocaine”—finding what happiness and fulfillment she could in her circumstances.

The better representation of a nihilistic approach is what Chidi flirted with after becoming aware of his impending eternal doom in the episode “Jeremy Bearimy.” Making his vile Peep‐M&M‐chili concoction in the middle of class, quoting Nietzsche’s immortal lines about the