Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: September Publishing

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

- Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

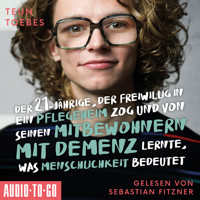

The international bestseller - an uplifting story of cross-generational living and friendship. Twenty-one-year-old nursing student Teun Toebes (both broke and curious) decided to move into a nursing home and experience the daily life of elderly residents, not as a nurse or a carer - but as a housemate. The experience was to change his life, as well as the lives of his new friends. He initiated Friday drinks, trips out and camping evenings, and reintroduced pleasure in the small things in life: a laugh, a dance, a cup of good coffee, a chance to sit in the sun. As he became embedded in the community, however, Teun became more and more distressingly aware of how society and the care system diminishes the elderly and particularly people living with dementia - and he resolved to do something about it. A number 1 bestseller in the Netherlands, The Housemates is Teun Toebes' story of his years of being a housemate, the friends who changed him and a heartfelt cry for change in how we care for the elderly.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 212

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Sammlungen

Ähnliche

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

First published in 2023 by September Publishing

First published in the Netherlands in 2021 by De Arbeiderspers, Amsterdam, with the title VerpleegThuis

Copyright © Teun Toebes 2021, 2023

Translation copyright © Laura Vroomen 2023

This book was published with the support of the Dutch Foundation for Literature.

The right of Teun Toebes to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Teun Toebes wrote The Housemates in close collaboration with documentary maker and author Jonathan de Jong.

Front cover photo, Teun and Eugenie: Annabel Oosteweeghel Back cover photo, Teun with (from left to right) Jeanne, Ad, Juul, Elly, Eugenie, Tineke and Petra: author’s own

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright holder.

Typeset by RefineCatch Limited, www.refinecatch.com

Printed in Poland on paper from responsibly managed, sustainable sources by Hussar Books

ISBN 9781914613395

Ebook ISBN 9781914613401

September Publishing

www.septemberpublishing.org

‘Life here has no purpose, and when you no longer matter you might as well be dead’

Muriëlle Mulier – housemate

Dementia in numbers

In the UK, there are 944,000 people estimated to be living with dementia; this is due to increase to 1.6 million by 2050.1Dementia cost the UK economy an estimated £25 billion in 2021.2In the USA, of those at least 65 years of age, there were an estimated 5 million adults with dementia in 2014, with projections to be nearly 14 million by 2060.3In the US, in 2023, dementia will cost the nation US$345 billion (this does not include the value of unpaid caregiving).4Globally, more than 55 million people have dementia. This will increase by 10 million each year.5In 2019, dementia cost economies globally US$1.3 trillion (about 50 per cent of these costs are attributable to care provided by informal carers).6Contents

Dementia in numbers

Preface

I. Seeing the Light

My heart’s been stolen

An open mind

The first steps

II. Between Hope and Fear

Life after death

The big why

The house rules

III. Safety First

Reality check

Perfectly normal

2017

IV. I Think, Therefore I Am

Things were better in the old days

Silent night

I haven’t lost my mind, you know

Normal life

Human forever: A conclusion

A cry from the heart

My friends in their own words

Ethical considerations

Afterword: The path of most resistance

Notes

Acknowledgements

About the author

Preface

My name is Teun Toebes and I believe that people living with dementia don’t get the care and attention they deserve. It makes me incredibly sad. Not only because I love my housemates with dementia dearly, but even more so because this could be my future if I ever receive the diagnosis myself. After a life of freedom and self-determination, who’d want to end up in a system of indignity and exclusion? Who’d want to spend his or her final years as someone who’s no longer seen as an individual, but as one of a group of sick people who’ve lost the plot? Who’d look forward to living in a home where the long corridors echo with loneliness and the TV blaring in the lounge is the only sign of life? Do you fancy such a future for yourself? I didn’t think so! It has to change and that’s why I’ve written this book.

The Housemates is a heartfelt indictment, not against the care sector, but against the way our society views people with dementia. Is it a devastating indictment? Absolutely, because life in a nursing home is devastating – it’s something I encounter every day.

This isn’t the truth; this is my truth and I admit it can be confrontational at times. But I hope my story will lead to dialogue and new insights, so that together we can make some much-needed improvements to the care we provide for people with dementia. We need to show that those living with dementia can still have a meaningful life; once we realise this as a society, the nursing home – my home – will have a hopeful future.

A better future sounds good, of course, but what’s the situation like right now? When you’re diagnosed with a form of dementia today, you go down a medical pathway with a great deal of attention placed on ‘the patient’ and lots of discussions about you. You’ll live at home for as long as possible, until your condition deteriorates and it’s no longer viable for either medical or social reasons. Or until your carer, often your partner, breaks down. The next step is a nursing home, where you’ll find yourself in a mini society with all the hallmarks of a totalitarian regime. Did I really just say that? Yes, and I mean it, but like everybody who works in the care sector, I say this with the best of intentions. To my mind, the fact that the nursing home is set up in such a way as to exert total control over my life and that of my housemates means that it bears little or no resemblance to a democratic and equal society.

Just to be clear: I’m not writing this to make things difficult for my colleagues in the care sector or to portray them as a bunch of careless pencil pushers – far from it. I actually want them to have the freedom to change the way they think and act, and to discuss among themselves how care is provided and, above all, why it’s done in the way it is now. That’s what I’d like to achieve with this book. As a young care assistant, I’m so frustrated by the inhumane treatment of people with dementia today that my motivation to do this work is melting away like snow in the sun.

As much as we try to give loving care, as providers we appear to have lost sight of the essence. The current system is undermining lasting human relationships and is moving towards a model of medicalisation that fails to adequately see individuals for who they are. It looks as if it’s almost all about money, appointments and expertise, and we’re losing track of the people we’re supposed to be looking after. I believe that we need to be attentive to the wishes of individuals with dementia and that the care for these people must – and can – change.

If we want to implement real change and humanise care, we must start by asking ourselves the fundamental question: what does it mean to live with dementia?

With that question in the back of my mind, over a year ago, I moved into a nursing home. This allowed me to experience life with dementia from a range of different perspectives: as a nurse and as a student of Care Ethics and Policy, but, above all, as a human being. My housemates and I have created special memories together and a dynamic and loving relationship. With them, I feel that I experience the crux of human existence.

It’s truly wonderful to be able to call this environment my home. I feel privileged to learn from these fine people and to discover more about their inner world. But most amazing of all is that every day I get to share in the happiness of people who in the eyes of society are incapable of being happy.

That’s why I dedicate this book to those who are so often forgotten: people living with dementia.

I

Seeing the Light

My heart’s been stolen

If you’re talking to Teun, it’s bound to be about dementia,’ those around me have a habit of saying. Every day, I get asked where my passion for people with dementia comes from. And no wonder, as it’s not exactly a topic you’d expect to come up at an average twenty-two-year-old’s birthday party.

Everybody assumes that dementia runs in the family, and it does, but that was certainly not what first drew me to it. My interest was piqued on a work placement during my nursing course. I ended up on the secure unit of a nursing home dedicated to people living with dementia. I must confess that it was a lot to take in, as what I saw didn’t exactly correspond to the idea I had when I enrolled in the degree.

Perhaps I was a bit naïve, but, like many, I grew up with US television series about handsome doctors and young nurses who save the world while busy dating each other. Of course, I knew that this portrayal of the care sector wasn’t entirely accurate, but the reality was such a let-down that I wanted to call it quits straightaway. Those people who sat around long tables staring into space all day made me feel uneasy. Was this my future, I wondered? What difference could I possibly make in this dreary world behind closed doors?

As sweet as my mother usually is, there are times when she’s unexpectedly feisty and tough. When she heard me moan about my degree choice, she told me in no uncertain terms that quitting wasn’t really an option. ‘Good care can only be provided by caring people and if there’s one thing I know, my boy, it’s that you’re one of them.’ Although I was well aware that my mother, who works in the care sector herself, is more than a little biased, I took the compliment and, a week later, I went back to the ward with some healthy misgivings.

I had a look around, chatted a bit and had the odd cup of tea. Then I suddenly realised something that, as an adolescent boy, I really didn’t want to: my mother was right! Right from the off, I enjoyed my contact with the residents, especially when I met John Francken, a former construction foreman. It was because of him that I grew to love the care sector as well as people with dementia, and not just him. He showed me, a seventeen-year-old, that as a society, we don’t properly understand ‘the nursing home resident’ because we just don’t want to accept that ‘they’, in their own remarkable interior world, have exactly the same needs as ‘we’ have in the outside world.

‘Listen up, Teun,’ John said. ‘My whole life, I got treated normally, until the doctor said: “You’ve got Parkinson’s.” It was all downhill from there, not so much with me, but more with the way people behaved towards me and talked about me. The contact with my old workmates changed, neighbours looked at me differently because they felt sorry for me and I was constantly being asked if I was all right. So basically, my life as a normal person was over … And I don’t blame them, pal, because nobody on the outside knows anything about this bloody disease. But what I do mind, Teun,’ he continued, ‘is how I’m treated inhere, where it’s full of people who have something wrong with them and who bloody well know it. You’d expect the staff to recognise that we’re not barmy, that we’re not all the same or at the same stage of the illness. Shouldn’t we be normal in here, of all places? But they’re treating me like I’m bonkers, like I don’t know what I’m doing, don’t matter anymore. They forget that the man they’re looking at is John Francken, and that this man has had a good life and used to enjoy the little things – a bit of banter, a joke, or even just people walking past the building site with a spring in their step. They forget that this very same man still loves all that, even if I’m confused sometimes and I forget things. I may be forgetful, but from the day I moved in here, pal, they’ve forgotten about me, not the other way round …’

Gulp. For a moment, we looked at each other, speechless and with tears in our eyes. For a moment, there was no tough guy sat opposite me, but a human being with the sweetest yet saddest expression I’d ever seen. Then I cleared my throat and said gently: ‘I won’t be doing that, John. I won’t forget you, I promise.’

Because of that promise, I felt I had something to prove to John, and that is that as a society we can listen to him and the thousands of others living with dementia. And so John not only became my buddy, but the inspiration behind my mission to improve the quality of life for people with dementia. And that mission began right there and then.

In my free time, I’d go out for ice cream with John. We’d laugh at some of his rather sexist ‘builders’ jokes’ and race around the village in my car, insofar as that was possible in that old rust bucket of mine. And, as the icing on the cake, yours truly, a somewhat vain nurse-in-the-making, was the only person on the ward allowed to trim John’s moustache. Perhaps not that great an honour on the face of it, but anyone who knew John would understand. John not only taught me to really look and listen to people with dementia, he also showed me something I hadn’t been able to see during my first visit: the human being behind the illness.

A second reason for wanting to help people with dementia came several years later, when my grandmother’s younger sister, Greet, was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s, the most common form of dementia. I remembered Greet from my grandma’s milestone birthdays, when she’d be the one moaning and complaining about other people. I also recalled that she was always dressed to the nines, wearing pearls. Greet had been alone for much of her life: her husband had died young, leaving her involuntarily childless. To have something to care for, Greet got herself two pooches – a couple of lapdogs, or ‘yap dogs’ as she called them. Every year, she had their portraits taken, both of them wearing a red bow, and gave the smartly framed photograph pride of place on her wall.

Greet had little or no contact with the rest of the family, but as she got older she developed a closer bond with my aunt, her niece. When Greet was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease – after a long period of shame and concealing her symptoms – my aunt became her legal guardian and was given lasting power of attorney over Greet. At the time, I didn’t give it a second thought, but it’s a formality that epitomises what your life is like from that moment on: a life without an official voice, free will or self-determination. A life in which you’re legally no longer heard, simply because you don’t have the right to speak, whatever you say. Perhaps it’s this stroke of the pen that’s inadvertently at the root of how, as a society, we view people with dementia.

The moment she was diagnosed, Greet began to withdraw even further. Her blinds remained resolutely shut and the meals she received from relatives were immediately passed on to the dogs – their welfare was paramount to her. But sometimes she’d forget that besides dementia she also had diabetes, a combination that can be dangerous, as we found out when the police had to force entry twice while Greet was unconscious on the floor. It became clear that it was no longer safe for her to live at home, in the house where she’d lived her whole life. That came as a huge shock because her autonomy was perhaps most precious to her – not surprising when you think that for much of her life she’d had to fend for herself. But after a good conversation with my aunt, Greet agreed that her safety was at stake. With hindsight, she might have chosen to accept that risk rather than go along with what was in store for her.

All that was needed now was a court order to set the move to a nursing home in motion, which followed soon after. Maybe it was because there was family involved or because this was the first time I saw how people ended up in a nursing home, but I couldn’t stop thinking about the fact that a woman was forced to leave her house after fifty-eight years. What must that feel like, especially when you don’t always understand why you had to leave? It’s no wonder that most people are terrified when they move into a nursing home, something that never fails to hit a nerve with me. Surely there has to be another way? Even in terms of design and layout, a nursing home is so different from a private dwelling that residents rarely, if ever, feel at home. That is not to say that nursing homes should be abolished, because remaining at home wasn’t an option for Greet. But living in fear shouldn’t be either.

As chance would have it, I worked in the nursing home that Greet moved into. Hand in hand, we entered the living area, where she sat down on the chair closest to the window. That turned out to be no coincidence. ‘Right, this spot is mine, boy. At least I get to choose something in here,’ she said cynically, as her eyes drifted to the fenced-off garden.

I soon became my great-aunt’s point of contact for anything care related. It was an unusual dual role: one moment I was a healthcare professional, the next I provided care out of love for my relative. And the good thing was that she also took care of me. She could sense when I was busy or struggling with something and she would always give me tailor-made advice. It was fascinating to see that she could read me so well and it once again confirmed my suspicion that not only can you connect with someone with dementia, but you can establish a lasting and reciprocal relationship too – even if you have to go about it differently. This took a while to sink in because it wasn’t at all what I’d learnt on my course. My realisation set something off in me, which further strengthened my intention to improve the quality of life for people like my great aunt.

To me, the two separate roles of official care provider and informal carer were complimentary, if difficult at times. Not least when I was consulted about major decisions, such as how long we’d want to continue medical treatment if her symptoms worsened. Such questions are tough for any twenty-year-old care assistant, but even more so when your own family is involved. Being an informal carer was totally new to me and, like so many others, I was trying my hardest. The personal care, on the other hand, didn’t take any getting used to. To my surprise, I felt privileged rather than awkward about taking physical care of Greet, and luckily Greet felt the same way. Before I could even hand her a washcloth, she’d already dropped her trousers and said: ‘Wash me, Teun.’ In no time, we’d established a strong bond and she’d often refer to me as ‘her boy’. But, proud as she was, she could look very jealous whenever I gave attention to her fellow residents.

In the months that followed, she changed from an unkempt and embittered woman into the lady I recognised from the parties in the old days. She looked chic again and was always over the moon when the dogs, her ‘woofies’, came to visit. Her character had remained virtually unaffected by the dementia, though, so she could still grumble with the best of them. When it came to her day-to-day freedom of choice or when something wasn’t to her liking, she could make things pretty difficult for the nursing staff on duty.

Most people won’t bat an eyelid when they read this next sentence, but I’ve chosen my words carefully as they capture the reality of care to a T: when people with dementia push back, they’re almost immediately branded ‘difficult’. Consequently, many ‘difficult’ people are sedated to the point of coma. Because, let’s face it, isn’t having a conversation with or offering a sympathetic ear to someone living with dementia basically pointless …?

This situation really pains me because why would diagnosis with a form of dementia determine whether a person can be happy or not? Why would such a diagnosis condemn you to hours of listening to André Rieu in the lounge when you’ve always loved the Rolling Stones and this kind of saccharine music – no disrespect, André – isn’t your cup of tea? Why does it result in flower arranging when you hate gardening, or listening to yet another choir that’s come to sing old, sentimental ballads when you’d much rather play Whitney Houston or the Beastie Boys in your room? Please explain to me why a diagnosis justifies this kind of approach and, above all, why it means that when you stand up for yourself, you’re robbed of your voice, either medicinally or through other measures? It doesn’t just sound daft, it is daft! In what kind of world do you get punished for standing up for yourself? Sadly, this was the everyday reality for John, later for Greet and, to my immense regret, for many others to this day.

This is not an attack on care providers but an indictment of a system that has created a huge distance between people with dementia and the rest of society. This system has not only made laws that say that people with dementia may be marginalised – and ignored when it comes to fundamental or personal matters – but it has also created a corresponding climate of care in which such marginalisation isn’t the exception but the rule. This system is the reason why nothing is changing, because once the absurd has been rendered normal through policy, you can’t expect those working in the care sector to defy the rules. Anyone who does tends to be seen as ‘difficult’ and that … that is something nobody wants.

As the months went by, Greet’s health declined. She was confused more often and would wonder where her parents were. I could feel her pain when she told me that her parents had passed away, but she’d been unable to attend their funeral. Or so she thought. As her brain deteriorated, so did her body. She often complained of pain for which she received medication, but the side effects meant she slept for much of the day. Slowly, her lungs began to give out. She wheezed as she clutched the humidifier.

After several weeks, during which the proud woman I’d come to know again had been increasingly absent, I received a call from one of the carers. Greet was in a bad way, would I come in to take a decision? After consulting with the doctor and the care coordinator, I called my aunt, her legal guardian, and suggested to her that it might be better to withdraw life-sustaining treatments. In our view, Greet’s suffering was no longer proportional to the better moments, so death would be a release for her. But it was a tough decision. Greet herself could no longer tell us what she wanted because she was in a deep sleep. My aunt backed the decision and I drove over to my grandma to inform her that the last remaining member of the family she grew up with was going to die. She was behind the decision all the way and together we made our way back to the nursing home.

Soon after, the moment came to start palliative sedation, which involves administering medication to put someone in a deeper sleep and relieve suffering. In principle, a person can still wake up when the medication is withdrawn before their heart stops beating. My grandma was astonished when we explained this to her: ‘Why doesn’t it just end when you give that medication? Why leave someone to wither away for days?’ I nodded because I understood where she was coming from. They’re often very long and strange, those days of waiting while someone is dying. You can sense it. The atmosphere in the room is simultaneously ominous and heavenly. You find yourself in a kind of surreal no-man’s-land where every now and again, you’re brought back down to earth by gurgling breaths that come at ever-increasing intervals. Some people find this period restful because it provides an opportunity for an extended goodbye, but I was hoping Greet would quickly get to the other side. I brought my head close to hers one last time to thank her for allowing me to get to know her again. ‘Rest in peace,’ I whispered in her left ear, after which my grandma bid her sister farewell in her own way. ‘Bye girl,’ she said lovingly.

With a colleague by my side, I took the syringe with morphine and the appropriately named sedative Dormicum and slowly injected the fluid via a needle in Greet’s chest into her body. Two nights later, my mother woke me. It was done; her heart had stopped beating.

In the months that followed, I missed her terribly. Every day I wondered whether I’d given her the best possible life at the nursing home or if I’d been too blinded by acquired patterns of behaviour that had made my great aunt a ‘patient’. But the more I thought about it, the more convinced I became that I’d always seen Greet for who she was – that eccentric person with both good and bad qualities that I loved more and more every day – and not my sad great aunt with dementia. This filled me with hope. The ‘reimagining’ of patients into individuals seemed so easy to me that the future of caring for people with dementia looked a great deal brighter.

To test whether creating a better and more humane care sector is indeed as simple as that, I decided to raise my mission to a higher level by not only caring for people with dementia but by living with them as well. As in, actually moving into a nursing home? Exactly. A more inclusive society begins at home.

An open mind

As a care provider, I know that many nursing homes have empty rooms because for years – for a variety of reasons – there’s been a shortage of staff to look after residents. That’s the sad reality and, given the rising tide of people with dementia, it’s only going to get worse in the future.