Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Wissenschaft und neue Technologien

- Sprache: Englisch

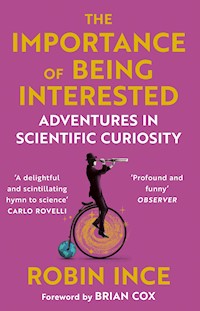

***A Waterstones Best Paperback of 2022 pick*** Perfect for fans of Radio 4's The Infinite Monkey Cage and Professor Brian Cox. 'A delightful and scintillating hymn to science.' Professor Carlo Rovelli Comedian Robin Ince quickly abandoned science at school, bored by a fog of dull lessons and intimidated by the barrage of equations. But, twenty years later, he fell in love and he now presents one of the world's most popular science podcasts. Every year he meets hundreds of the world's greatest thinkers. In this erudite and witty book, Robin reveals why scientific wonder isn't just for the professionals. Filled with interviews featuring astronauts, comedians, teachers, quantum physicists, neuroscientists and more - as well as charting Robin's own journey with science - The Importance of Being Interested explores why many wrongly think of the discipline as distant and difficult. From the glorious appeal of the stars above to why scientific curiosity can encourage much needed intellectual humility, this optimistic and profound book will leave you filled with a thirst for intellectual adventure.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 562

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

THEIMPORTANCEOF BEINGINTERESTED

Robin Inceis the co-creator and presenter of the BBC Radio 4 show The Infinite Monkey Cage, which has won multiple awards, including the Sony Gold and Rose d’Or. In 2019 he played to over a quarter of a million people with Brian Cox on their world tour which has put them in the Guinness Book of Records for the most tickets sold for a science show. He also won Celebrity Mastermind but forgot that calcium was the dominant element of chalk. His other books include I’m a Joke and So Are You and Bibliomaniac.

‘A delightful and scintillating hymn to science. Resolutely a non-scientist, Robin Ince discovers with awe that when science addresses the “big problems” and destroys familiar beliefs, it does not leave us in a cold, meaningless and dehumanized world, but in one that is colourful, human, and full of intensity and wonder.’

Professor Carlo Rovelli

‘Ince makes profound – and funny – reflections on our tiny lives in a massive universe.’

Observer

‘Robin is the most engaging of science communicators… I found this book by turns challenging, entertaining and moving.’

Steve Backshall

‘With razor-sharp wit and insight, Robin slices into the biggest questions of our time. The Importance of Being Interested left me smiling and thinking more deeply.’

Commander Chris Hadfield

‘Brilliant and entertaining. Science is done by humans, and humans are the only reason that science matters: curiosity is part of human nature, but sometimes we need reminding just how much is out there to explore and enjoy.’

Dr Helen Czerski

‘Will gladden the heart and stimulate the mind… Sparkling.’

Independent

By the same author

Robin Ince’s Bad Book Club

I’m a Joke and So Are You

Bibliomaniac

With Brian Cox and Alexandra Feacham

The Infinite Monkey Cage – How to Build a Universe

First published in hardback and trade paperback in Great Britain in 2021by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

This paperback edition published by Atlantic Books in 2022.

Copyright © Robin Ince, 2021

The moral right of Robin Ince to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Paperback ISBN: 978 1 78649 264 7

E-book ISBN: 978 1 78649 263 0

Chapter header illustrations by Mecob, based on images from Shutterstock.

Internal illustrations: p36 © Getty Images; p91 © Robin Ince; p103

© Wikimedia images; p138 © European Space Agency; p168, p355

© NASA; p353 © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2021.

Printed in Great Britain.

Atlantic Books

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

To all the librarians and teachers who haveencouraged our curiosity,

And to my sister,sometimes Camilla, sometimes Janey,depending on whether my parentsthought she was being good or bad,who has maintained her fascination with the worldwhile often keeping it turning for other people.*

* This now puts huge pressure on me to dedicate my next book to my other sister, Sarah. I will try to write one as soon as possible.

Contents

Preface to the Paperback Edition

Foreword by Professor Brian Cox

Introduction: The Stars Your Destination

CHAPTER 1

Scepticism – From the Maelstrom of Knowledge into the Labyrinth of Doubt

CHAPTER 2

Is God on Holiday? – Are There Still Enough Gaps for a God?

CHAPTER 3

Armchair Time-Travel – Putting Out Your Beach Blanket on the Sands of Time

CHAPTER 4

Big, Isn’t It? – On Coping with the Size of the Universe

CHAPTER 5

Escape Velocity – On Looking Back at the Planet from a Height

CHAPTER 6

Why Aren’t They Here? Or Are They…? – On Waiting for Our Alien Saviours

CHAPTER 7

Swinging from the Family Tree – Inviting Yeast to the Family Reunion

CHAPTER 8

The Mind Is a Chaos of Delight – On the Matter of Grey Matter

CHAPTER 9

Reality, What a Concept – Can Anything Be What It Seems?

CHAPTER 10

Imagining There’s No Heaven – On Being Finite

CHAPTER 11

More Important than Knowledge – On the Necessity of Imagination

CHAPTER 12

So It Goes – Facing Up to the End of Everything

Afterword

Notes

Acknowledgements

Preface to the Paperback Edition

This book was written during a time of disconnection.

I wrote it in the first lockdown and edited it in the second.

It was this isolation that brought home to me the importance of creating a sense of connection from what can be found around you. It is wonderful to look at springtime blossom, for example, and think about how the entangled branches of the tree of life reach far back into the history of the universe, for us and every living thing you see. Before there was any life to be curious, there was a point when all the matter around us and within us was in the process of being formed.

This was a very hard book to edit, because I was fascinated by everything I learned from the people I spoke to. My editor questioned the length of the Jane Goodall interview:

‘It looks to me like you’ve just put in everything she said?’

And he was right.

It’s Jane Bloody Goodall.

The same goes for many others in this book. I spoke at length to Neil Gaiman about geology and storytelling, Brian Eno about the differing natures of art and science, Helen Sharman about the experience of observing our planet from beyond the atmosphere. I was lucky that I could have such adventures even though I was unable to go much further than my attic.

After the book was published, when restrictions lifted, I travelled to over a hundred bookshops in the UK and talked to audiences about some of the things I had discovered. Having this real connection with people was life-affirming. They had been inside for so long that they were brimful of questions about black holes, God and gods, starlight and how crayons are made.

I am not a scientist and, as I get older, I have become more comfortable admitting my ignorance. When faced with such questions I am not afraid to say, ‘Sorry, I don’t know’, and then point people in the direction of an author, a YouTube channel or wherever I thought someone could enlighten them.

What I found interesting was that each time I said this people would tell me afterwards, ‘Thank you for saying “I don’t know”.’ This took me by surprise. I was being thanked not for being informative, but for admitting my ignorance. It underlined to me that we live in a culture of the cocksure. It is seen by many to be better to pretend you know than admit you don’t, and when this is done by people with power and responsibility it can lead to us living in an increasingly delusional world.

For me, the most interesting conversations happen when people explore an idea together rather than just telling each other why they are right and the other person is wrong. Too many of our conversations are set up as debates to be won rather than conversations to be learned from.

I tried as much as possible in this book to be open-minded, though not to fall too far into a post-modernist mode of thought in which every belief about reality is of equal worth.

What I hope comes across is the need to be less fearful of uncertainty, and instead be invigorated by doubt and excited to be rare and aware.

Just after I finished the very final edit on the book, I was on my way to one of my favourite music festivals, Beautiful Days. It had the loveliest of audiences, united by ambitions to create a fairer world, as well as by intermittent face painting and drinking cider to just the right point of happiness.

Sat on Wembley Central station platform, I was thinking about the connection I feel when I look at the stars. I was thinking of both the wonder of being alive and the problems that can come with it. I thought of news of distant stars observed so far away that they may no longer exist. I was thinking of a beauty that can only exist because of a fragility. All that we see comes from disorder and entropy, briefly stable and magnificent to our eyes.

With ten minutes to spare until the train to Paddington, I wrote this poem:

Last night

A ghost collided with my head

It was the light from something dead

Once

It breathed hydrogen into helium

Created a beacon

Projected its life across the sky

And some of its life hit me in the eye

And expanded my mind

In its size

And in its power

It had been grander than I could ever be

It never knew how grand it was

It never knew the awe inspired

It never experienced its existence

There was nothing it was like to be that star

Only something it was like to marvel at that star

Because

The stars cannot wonder about the stars

And Jupiter too

Is without curiosity

Me?

I am small

And I’m fragile

I’m easily felled

By meteorites

or by microbes

But

I’m pugnacious

Inquiring

Tenacious

I can chew on the quandaries of the cosmos

I’ve got a skull full of questions

And pictures

And problems too

I don’t like my anxiety

But It’s also my fire

Much that destroys me

Also creates me

There is something it is like to be me

And it is not always satisfactory

My atoms battle

My molecules revolt

Yet still more than

A solo chemical reaction

Or the single line of an equation

Confused

Confusing

Absurd

But flashes

of inspiration

And out of my ashes

May grow apples

Emergent complexity briefly defeats the void.

I made myself perform it that night, unsure if it was gibberish.

Afterwards, a physicist approached me. She was both my age and in tears. She said she’d recently been diagnosed with ADHD and things were finally beginning to make sense after many years. She had found something in that poem that I had not known I’d put there (I’ll tell you my ADHD story another time).

This jumble of words that had come to me unprompted – with seemingly little conscious thought – had made a connection and it felt wonderful.

I hope you are able to celebrate your complexity and rejoice in your possibilities, and I hope that something you read in this book may give you reason for a new adventure.

Robin Ince

May 2022

Foreword

Richard Feynman once wrote that scientists’ most valuable transferable skill is a deep and intimate experience with doubt. It’s difficult to motivate yourself to spend a life in research if you believe you know everything, and even the most self-confident research scientist will ultimately be humbled by their encounters with Nature. This is the best argument I know for maintaining at least a small component of science throughout every citizen’s education. I once half-jokingly wrote that the PPE course at Oxford, studied in the loosest sense of the word by many a cabinet minister, should be rebranded PPES; perhaps brushing up against Nature occasionally would moderate their certainty. After all, as Feynman also pointed out, democracy itself rests on the acceptance that we don’t really know how to run a society; that’s why we change our politicians every four or five years. If you think you know how to run a country, if you think your policies are absolutely right and the other lot are absolutely wrong, you are not a democrat.

Robert Oppenheimer came to similar conclusions in his 1953 BBC Reith Lectures. Nature forces us to hold seemingly contradictory ideas in our heads in order to understand what we observe. A thing as simple as an electron is sometimes best thought of as a wavy, extended object and sometimes as a point-like speck. Crucially it is neither, but both pictures are necessary components of our understanding. Similarly, society may appear to be riven by tensions between the competing human desires for individual freedom and collective responsibility: but riven is the wrong word, because both desires are present in every individual and both are therefore necessarily present in society. The democratic process gently swings the pendulum one way and the other, and the swing is both the manifestation and guarantor of our freedom.

Your freedom, then, is protected by your acceptance that you might be wrong, and science is a sure-fire way of forcing you to practise being wrong. Which brings me neatly to my friend and colleague Robin Ince. He describes his role on The Infinite Monkey Cage as that of professional idiot. He means this in a self-deprecating way; indeed, he has elevated heartfelt self-deprecation to something of an art form. From his wardrobe to his gait, he radiates uncertainty. But, as I have argued, there is no more valuable skill. There are two categories of idiot: the curious idiot – a category that includes all scientists – and the idiot – a category that includes all who are certain. Robin is a category one idiot, and that’s why he’s an engaging and wise guide.

Robin’s thirst for knowledge is unquenchable, and in these pages he engages in debates and conversations with a dazzling cast of great minds in search of a little enlightenment; not absolute enlightenment, because that’s not on offer. We do not understand the human mind, we do not know what it means to live a finite life in an infinite universe, and we do not know whether or not there is a God. If answers exist, they reside in unknown terrain, and that’s what makes them interesting. It’s important to explore that terrain with humility and an open mind. It’s important to be interested.

Brian Cox

July 2021

INTRODUCTION

The Stars Your Destination

In studying how the world works we are studying how God works, and thereby learning what God is. In that spirit, we can interpret the search for knowledge as a form of worship and our discoveries as a revelation.

Frank Wilczek

The moment I put my hand in my school-blazer pocket and found it full of frog entrails, I already knew science was not for me.

As a young child, I loved science. Primary-school science classes were full of excitement, whether it was interrogating leaves or watching Robert Calvert see blood and then faint and smash in his front teeth. In secondary school, though, this joy evaporated. I think many people lose their interest in science at secondary school, and I was one of them. This is where science became serious, but also where it became joyless. This is where the equations and explanations seemed detached from my own experience. Whatever science was, it was not lived experience. It was as if scientists only thought in sums. They didn’t daydream and play. Each day they opened their box of numbers and symbols and moved them about until they were satisfied: ‘I’ve carried the two and now I am satisfied that I have a testable wave function.’

That was predominantly how I felt about science at school. My curiosity about the world never went away – I just ignored it. I’d be thrilled to see an afternoon of art on the timetable, whilst to know that double physics was coming was to foresee time moving slower than Einstein could ever imagine. The division between the arty and the science subjects seemed jagged and high. The two cultures were clearly growing in separate Petri dishes.

Our physics teacher, Mr George, was a clever man, but the sort of person who didn’t understand people who didn’t understand. He was also easy to antagonize, and so the bullying, disruptive boys would hide his pens and see him explode apoplectically. They would giggle as he held back tears. It was a horrible sight, made worse after I read The Lord of the Flies, as I now knew exactly which of the boys in my class would be the ones shattering my glasses and throwing me off the cliff onto the rocks below. Putting frog entrails in my school-blazer pocket was simply the beginning of what might be possible.

My chemistry teacher had clearly lost interest many years ago. Biology had a little more pizzazz about it. There was the relative excitement of watching incubated locusts shed their skins. Then there was Mr Rouan, head of the department, who still had an enthusiasm about his subject and was always ready with a slightly inappropriate biological quip. I remember a nervous colleague of his embarking on sex-education hour, demonstrating how to use a condom with a broom handle playing the part of a priapic penis. The teacher’s shaking hand lost its grip on the broom and it fell to the floor, just as Mr Rouan passed the doorway and made a rude joke. We all laughed loudly as we pretended to understand.

But mostly I remember the mind-numbing effect of an afternoon double-physics class, head on the desk, drooling over my exercise books as the teacher plugged away at speed and mass equations. A dismal result in a physics exam, and an increasing sense that science was detached from the real world, finally put the nail into any delight in science. The tables where the science boffins sat had a strange aura of unknowable exclusivity. It was clear to me they had different brains. They understood this stuff. They were the Midwich cuckoos, otherworldly and somewhat threatening.

Now I wonder how on earth I ended up co-hosting The Infinite Monkey Cage, the long-running radio show and podcast. My early adult life was spent building a career in comedy, but sometime in my mid-twenties I bought a book about quantum physics. I didn’t really understand it, but I realized that what I wasn’t understanding was very exciting. I carried on reading books I didn’t understand, with only small glimmers of occasional comprehension. I started to refer to some of the ideas in comedy routines, then I began to base whole shows around them, and from there it only seemed right to ask whether real scientists could join me onstage to make sense of my confused ramblings. This eventually led to The Infinite Monkey Cage with the physicist Brian Cox. Then I started joining him on tour, where he would explain high cones and holographic principles, and I would ask the dumb questions I realized I’d always wanted to know the answers to, and that others might be afraid to ask because they feared they might look stupid.

At the time of writing there have been 150 episodes of The Infinite Monkey Cage and it has covered everything from the theory of relativity and the Higgs boson, to how science proves that it is best to eat a pear with a golden spoon, and how to speak fluent chimpanzee. I have spoken to Nobel Prize-winning geneticists, Apollo astronauts, undersea explorers and one wizard. Such work has often meant that I’m in the fortunate position of usually being the stupidest person in the room. It’s not always good for the ego, but it is very good for my education. W. H. Auden wrote that when he was in the company of scientists, he felt ‘like a shabby curate who has strayed by mistake into a drawing room full of dukes’.1 I am pretty happy to be the shabby curate. I’ve got the wardrobe full of cardigans, and I come from a long line of vicars, so I have that ecumenical gene.*

The way the guests on the show explain and talk about science – the way they make it relevant to everything about my daily life, my existence here on this planet, the past, the present and the future – has rekindled my enthusiasm and widened my curiosity for a subject that died a death on the Bunsen burners of my youth.

I’ve realized, though, that whilst much can be made of what we have gained from scientific knowledge, for all the enthusiasm and passion of the scientists I speak to on the show, much can also be made of what has been lost. For some people, while science has given us the power to do things, to create, to control and to live longer lives, it has also delivered a longer life that now seems meaningless. Some say that science has robbed us of our gods, our exceptionalism, our centrality, our free will, and leaves us lost and alone in a vast universe. I can understand why some may feel this way, if they merely glance at the knowledge we have gained from science, but I believe that the deeper you explore science, the more our new knowledge creates rich stories, new enchantments and, rather than leaving us alone, connects us to everything. But I am getting ahead of myself; let’s go back to the Garden of Eden and start again.

Did it all go wrong when we ate from the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge? Before then we were living in blissful ignorance, but then curiosity kicked in, and with that curiosity came questions and doubt. Some suppose that the universe was enchanting when we knew nothing of it. The lights in the sky twinkled because they were attached to a celestial sphere or shone through the holes of a heavenly curtain; but then they became nuclear reactors, shining as hydrogen became helium, some of them destined to collapse into something so terrible and mighty that even light could not escape. Your downfall begins the first time your face creases into a frown and you say, ‘But why?’

‘Don’t ask why, just get on with it!’

The best way forward for some people is to stay exactly where they are. ‘Ours is not to reason why…’ Perhaps there’s a fear that if we pull back the curtain, we might be disappointed by what we see. ‘Pay no attention to that man behind the curtain. The great Oz has spoken,’ says the charlatan in The Wizard of Oz, although the result of the revelation that the great Oz is simply a man with a megaphone and a smoke machine actually leads to satisfying answers for all on such issues as the heart and the brain.

Curiosity, in particular scientific curiosity, is dangerous to the powerful. Power often rests on certainties, and the scientific method encourages active doubt. There are warnings to the curious. As Oedipus found out, ‘How terrible is wisdom when it brings no profit to the wise.’*

Questions can be seen as impertinent and dangerous. You may lose everything you hold dear – your god, your afterlife, your free will, your feeling of superiority, your mind… even your entire reality. Knowledge can be framed as loss rather than gain. It is a quandary I have been dealing with for the last fifteen years.

I often ask myself how scientists came to be doing what they are doing. Why weren’t they bored to tears in their science lessons? Do their brains work differently? What do they see when they are explaining quantum indeterminacy? Are they born with scientific brains? Is the ability to understand supernovae or charm quarks somehow hard-wired? This was one of my first anxieties when I started making science shows. Was I allowed to think on such things? Did I have permission even to ponder these subjects, without qualifications? Scientific ideas can seem so daunting that they may feel both forbidding and forbidden. Any question from a novice like me surely has a high probability of being a stupid question.

It can be easy to believe that scientific ability is built into us by a quirk of nature – our genetics. If you find science hard, it is because your father found it hard, and your father’s father found it hard, and you have inherited the ‘not understanding cosmology’ gene. This was how it seemed to me. I struggled with learning science at secondary school and ended up believing that I didn’t have the correct configurations in my brain to check into Hilbert’s Hotel or diagnose Schrödinger’s cat. I don’t think I’m alone in believing this; but that so many people should presume they are unfit for science perhaps suggests there is something wrong both with how we learn science and with what we believe it to be.

Even Carlo Rovelli, who is a founder of the loop quantum gravity theory and a writer of very beautiful books on physics, struggled with the tedium of some of his science education, but he was able to see beyond it. As he writes in his book Helgoland, ‘What attracted me to physics was that beyond the deadly boredom of the subject taught in high school, behind all the stupidity of all those exercises with springs, levers and rolling balls, there was a genuine curiosity to understand the nature of reality.’ Fortunately I have found a way back into feeling a fascination about science, though I can assure you that I will not be contributing anything of any significance to loop quantum gravity theory.

I have totted up daily the pros and cons of confronting my ignorance, and I am pretty sure the advantages outweigh the disadvantages. Sure, it means I now live in a meaningless universe, by the looks of things, but existential philosophy was eager to tell me that, before astrophysics ever got involved. If you want to feel frighteningly alone in the universe, sit on a railway-station platform in midwinter, waiting for a train that increasingly looks as if it will never come, and read Jean-Paul Sartre: ‘Every existing thing is born without reason, prolongs itself out of weakness, and dies by chance.’ And then he doubles down on that with: ‘It is meaningless that we are born, it is meaningless that we die.’* These are the sorts of aphorisms that would lose you your job in the fortune-cookie factory.

Professor Brian Cox is very fond of the words of John Updike: ‘Astronomy is what we have now instead of theology. The terrors are less, but the comforts are nil.’ But does this mean there are no comforts or consolations from science, bar perhaps the temporary consolation of medical ingenuity, spaceships and instant-whip desserts?

Sometimes it can be hard to start the day with a spring in your step when you have been made aware that you are merely a perturbation in the universe’s wave function. The last few centuries have seen our uniqueness being whittled away – we are no longer at the centre of the universe, no longer a special creature separate from those grubby, ball-licking, poop-flinging animals. Like all of the rest of them, we are just a quantum fluctuation, although a quantum fluctuation that combs its hair and plays Scrabble.

Physicists usually seem the least bothered by such a demotion. I think it is because they see things either at an atomic level or wave-function level, and find the recycling of these patterns and subatomic particles satisfying enough. Biologists seem a little more concerned, perhaps because they observe things at a more molecular level and smell the organic decay. Chemists generally don’t have time for either position, as they are too occupied with wondering why people don’t talk about chemistry enough. Chemistry is the middle child. First there was physics, the older sibling; finally there was biology, the spoilt child; and in between, chemistry came into the universe: essential, but often overlooked.

The physicists seem to have got so used to the indifference of the universe that they forget it might be news to other people, and they forget the need to break it to us gently. This can lead to nihilistic flourishes at public lectures and debates, which can be deeply disturbing. They bandy about our inconsequentiality and expect us to sit obediently, taking it all in. We are just a bunch of atoms. Everything is just a bunch of atoms – Chartres Cathedral, the Grand Canyon, a blue whale, Jupiter. Cancel your travel plans; you can simply stare at all the atoms that you have at home; they may well form something magnificent one day, so enjoy them while they take the shape of your desk-tidy or pan-scourer. It is like returning from a world tour and dismissing the Great Wall of China as ‘just a load of bricks’.

Our experience and sensations are all down to nothing but firing neurons. You are merely calcium ions, firing away. Even our selfhood may be an illusion, as is our autonomy. We’re on a humdrum planet. We’re in a corner of the galaxy that is unexciting. Our galaxy is mediocre.

You can see why scientists don’t always make the best motivational speakers, and why first dates can be tricky, because not everyone wants to know the number of bacteria living on the surface of their skin, before the starter. Yet again, though, it is the philosophers who most firmly bop us on the nose. The philosopher Bertrand Russell wrote, ‘The universe has crawled by slow stages to a somewhat pitiful result on this earth and is going to crawl by still more pitiful stages to a condition of universal death.’2

Some may see such statements as cosmological honesty, but, like a work colleague who says, ‘A lot of people in the office think you smell of Camembert stuck in a burnt-out clutch, and that your new haircut makes you look like Mao Tse-tung – just thought you should know’,* such plain speaking can be upsetting and a source of despair and depression, even if it might be true. ‘I speak as I find, and I find the universe to be indifferent, and destined to end leaving no trace of human creativity or indeed any knowledge, love or beauty at all. And how was your day at the office?’ If that has been your only experience of engaging with science, then I can see why many people decide not to return to it, but in my view that is in fact why it is worth sticking with. First may come disillusion, but then comes reenchantment. Some discoveries hit harder than others, but if you can get through that existential pain barrier, there are things on the other side (I am not one for running marathons, so I work out at the library instead).

With our loss of exceptionalism, there is also a gain of connection, and these connections can be found across scientific disciplines. You are not alone up on your Olympian heights; you are joined up to everything, and the loneliness of uniqueness is replaced with a new cosmological camaraderie. A scientist’s pessimistic realism is often the most coherent and quotable way of accessing their work, but after the humdrum, after the ‘cold and indifferent’, comes a big BUT…

I believe that within much of what can seem to be negative or pessimistic about our universe, there are many possible theories that can propel us, that drive us to find our own meaning and consolations – and hopefully that is what this book is about. You don’t have to depart from reality to find happiness and purpose. There are meanings in all this fragility; there is wonder and delight in all these doubts. Detaching yourself from certainty does not mean you must feel lost and bereft. The problem with ultimate truths and utter certainties is that they can get in the way of your adventures in ideas and can possibly block paths altogether. Accepting that the inevitability of life must be attached to the inevitability of death should sharpen the senses and the need to experience. The realization that to love is also to commit to loss is what magnifies that love.

Facing the realities of what scientific endeavour can tell us about the universe, and ourselves, can seem like facing up to the loss of things we have relied upon or held dear, but with the losses come gains that outweigh them, even if they are not always immediately apparent. I think the realization that there is no grand meaning to us – that we are not born with meaning stamped on us, but must strive for meaning, in all its tentativeness and potential fragility – makes it far more vital.

And yet for all these grand philosophical ideas about meaning, returning to actual engagement with science and scientists can be a bumpy road. Sometimes, many years after last burning your fringe on a Bunsen burner, reopening a science book can be a disappointing and frustrating experience. You start to read a book about quantum theory because, bizarrely, someone said it would help you understand how things may be alive and dead all at once, which sounds amazing; and you’d also really like to understand that Christopher Nolan film you have watched three times now. Dismayingly, though, as you plough through the book, it gets more and more complex, you fail to understand superpositions and entanglement, nothing seems to relate to what you really wanted to know; and you end up throwing your arms up in the air and presuming that you’re stupid and, once again, simply do not have the brain required. Sometimes the voice in my head shouting, ‘YOU DON’T UNDERSTAND THIS!’ is so loud that I can’t even hear the sentences I am reading.

At times the words on the page can seem to have a life of their own, independent of the reader. I have often found myself rattling my skull, desperate to work out where all the information that I have just read has gone. Was each sentence like a neutrino, passing through my eyes and skull without ever interacting with my brain?* Even if it does begin to make an impression, some of what you start to understand is aggressively counter-intuitive. Cosmological common sense seems to be in limited supply. For instance, it took me a very long time to get my head around the idea that there are 200 billion stars in our own galaxy alone.* Every time I said it out loud, I presumed I would be openly mocked.

Then I found out that many astronomers believed there were more galaxies in the universe than there were stars in our galaxy. Then I was told that the size of the universe could be infinite, which means there is someone else across the universe who has just read ‘the size of the universe could be infinite, which means there is someone else across the universe who has just read “the size of the universe is infinite”’ – and they have a head and life exactly like mine, or I have one exactly like them: different atoms, same life. That goes for you, too. And you.

That there is nothing special about me means that there are an infinite number of me’s. There are an infinite number of you’s, too. Then I read that we have to say ‘our universe’, because we are probably one of many universes. I bump into a quantum physicist who is keen to tell me about ‘many-worlds interpretation’, where everything that can happen does happen and, at the point of each potential event dividing, more worlds are created to allow all possible outcomes to occur. Now you have a multiverse of many worlds.

Another cosmologist butts in and tells me about the ‘holographic principle’ of black-hole thermodynamics, which suggests that all physical objects – including ourselves – are actually two-dimensional projections from somewhere else. On top of all that, I am still trying to get my head around the idea that my head, and everything else in the vast known universe, used to fit on the end of something smaller than the prick of a pin. Actually, even smaller than that – a sort of nothing-whatsoever size. Everything I have ever imagined was contained in something of infinite density, but no mass.

How could that be? I find it hard to close a suitcase if I try to put a spare pair of shoes in it, let alone a spare plant, hat stand or galaxy. It can all seem like the fevered imagination of a speed-pepped science-fiction author fearful of missing his deadline for Astounding Stories. You can see why people might shy away from science – never mind the numbers. It feels utterly absurd.

But if the universe was easy to understand, it would be a very boring place. When you see the professional public scientists broadcasting, they often seem sure, certain and infinitely polymathic. This is why some of the most important moments to watch out for may be when you see the scientists perplexed. When faced with a question to which the scientist’s reply is ‘I don’t know’, we can feel immensely relieved, but sometimes this can be followed by excitement. ‘Now you ask, let’s see if we can work it out!’

I remember standing with a physicist in front of an audience of 4,000, trying to work out how a Slinky moves downstairs. We came up with interesting answers, both of which were wrong, but even getting to the point of error was fun, and hopefully many people went home from that event, found their old Slinky and started their own research work. It hasn’t just been Slinkies, though; it’s been thinking about the edge of the universe, about the possibility that we are the only intelligent life in the universe (and that may well not be intelligent enough) and about the Sun swelling into a red giant. Sometimes such pondering is playful, and sometimes the air of doom becomes sweltering. And that’s really been my inspiration for this book.

When I first started re-engaging with scientific ideas, it was easy to get lost. It still is. It is a big universe and there are many ideas and theories about it, but the anxiety of not knowing where I am is not as jagged and forbidding as it once was. Scientific progress and development can fill people with confusion and fear, and it can challenge their most deeply held beliefs and connections, but I have lived to tell the tale and to want to learn even more stories. My mind has been repeatedly blown by the images and ideas offered by scientific thought and enquiry, and I am glad. I am getting used to doubt, and I am inspired by the seemingly inexplicable. I don’t need a quick fix any more. A little knowledge is only a dangerous thing if you think it is enough knowledge.

Brian Cox once wrote, ‘A little existentialism never did anyone any harm.’ But when I asked him about this, he admitted that he didn’t think he had ever experienced any existentialism; he simply imagined it might be useful for people who did. I am the anxious one in our partnership. Our temperaments are a cliché of art versus science. I am the fraught, antsy bag of nerves, while he coolly wanders towards the certainty of his own demise, safe in the knowledge that his atoms will survive, even if he doesn’t. Brian wouldn’t rail against the dying of the light; he would simply capture the light in an equation.

I believe that almost any loss that comes from the scientific adventure carries with it great gains, too – not merely pragmatic, but also enchanting and transcendent ones. Whatever idea seems to rob you usually contains a reward as well.

I wrote much of this book during the first lockdown of the Covid-19 pandemic. A positive outcome of the pandemic for me, in this regard, was that a number of people who would never usually have been available were kicking their heels at home, so bored that they talked to me. When I look at the wish list that I drew up at the beginning of 2020, the only person I failed to talk to was the film director David Cronenberg and, to be honest, it wasn’t so much that I needed to talk to him for the book; I just love The Fly* and I thought I could add a few paragraphs to the chapter on biology, dealing with the current genetic understanding of human–fly hybrids, which can be the outcome of drunken use of a teleport. As I talked to all the different contributors to this book, I have found the picture of the universe around me changing frequently. I think one of the purposes of bold human endeavours – whether scientific, philosophical or artistic – is to change how we see what we see, and possibly change ourselves with that.

Changing your mind is not always easy. These days, particularly across politics and on social media, it is easy to find people who would rather be aggressively certain than tentatively contrite or in doubt. Many seem to believe that it is better to be solidly wrong than wavering towards being better informed. But a common theme with the many people I spoke to was the need for inquisitive humility rather than righteous brutality, if we are to progress. And with that humility comes the need to interrogate yourself as much as you interrogate other people and to ask, ‘Why do I believe what I believe? What foundations am I standing on? And why do I favour them?’

We need to know who we are, in order to find out who we can be; to refute pointless barbarism and squabbles and build a world on common ground and collective understanding. I also believe that the more we confront the meaninglessness of the universe, the greater our ability to create our own meaning. I have tried to deal with the areas of understanding that have robbed us of our more comforting myths, but this has not robbed us of stories. The universe is still made of stories, and they have the comfort that they may well be true, too.

So I hope this book can do that for you. I hope you find something in it to enrich your picture of the world, or that you find some new enchantment on what might have seemed to be barren land. From my very first interview with the astronaut Chris Hadfield, a human who has watched the world turn beneath him, to my last interview with Carla MacKinnon, an artist whose experience of sleep paralysis means she has felt night-hags squatting on her chest, the shared underlying message of so many people has been that the more we explore and the more we learn, the better our questions become, the greater the adventure and the more connected we are, whether it is to supernovae or to octopuses. Life becomes easier to live when you start to understand it, when you don’t ignore the questions, when you don’t try and paper over your confusions, but open up to them.

By becoming acquainted with scientific curiosity, by learning and understanding from it, I believe we can be re-humanized rather than dehumanized. Perhaps we can be as beguiled by reality as we can be beguiled by myth, and can find room for both.

I am extremely timid, sensitive, impressionable, and with a great sense of mortality, lazy. Yet inside me there is another self completely unmoved by all of this, full of power and light.

CECIL COLLINS

Not explaining science seems to me perverse. When you’re in love, you want to tell the world.

CARL SAGAN

* Yes, yes, yes, I am aware that they have not really isolated the vicar gene. Nature and nurture vie their way to propel you to the pulpit.

* Obviously I would like you to think that I am quoting from Sophocles, though I’m really quoting from the Mickey Rourke film Angel Heart.

* When Jean-Paul Sartre was a little boy, he had lovely blond curly hair and his mother thought he was a beautiful angel. Unfortunately, while she was out, his grandfather insisted that his ‘girlish’ locks were snipped off. Without his curls, his mother thought he looked monstrous and, upon seeing him, ran to her room. That sort of thing can lead to a boy being a pioneer of existentialism.

* I should make it clear this does not come from personal experience. I have never had a haircut that made me look like Mao Tse-tung, though I did have some glasses that made me look a bit like Ernest Bevin.

* Neutrinos are a good example of being confounded. When I first read of how many pass through us constantly, I could not understand how something can exist with mass, but mass that is so small it passes straight through me. For the first few days after finding out about them, I am sure my body had an increased sensitivity and could feel at least a few of those 100 trillion neutrinos that were passing through me.

* I eventually found out how many stars there were in the universe: (approximately) 70 sextillion or, rather, 70000000000000000000000. Then I had to listen to whale song in a darkened room for a few days.

* And Scanners and Eastern Promises, and The Dead Zone and Spider and…

CHAPTER 1

Scepticism – From the Maelstrom of Knowledge into the Labyrinth of Doubt

Doubt is not a pleasant condition, but certainty is absurd.

Voltaire

Iwould love to be certain, to be sure of something, but my anxiety makes that unlikely. Perhaps my perpetual nervous doubt has had some advantages for me, as it has meant that whilst science has encouraged a deepening of my scepticism about the world, I have not had to painfully sever myself from any strongly held, dogmatic beliefs.

In his book Science and Hypothesis the French mathematician and physicist Henri Poincaré wrote, ‘To doubt everything and to believe everything are two equally convenient solutions; each saves us from thinking.’ Finding the Goldilocks portion of doubt – the doubt that is ‘just right’ – can be tricky. The author Robert Anton Wilson, who co-wrote The Illuminatus Trilogy, a wonderfully playful and adventurous romp through all the conspiracies there have ever been, encouraged universal agnosticism. This was not merely agnosticism about the gods; this was agnosticism for all your beliefs.

Good science is never certain. Though it might be sure it is providing the best answer for the time being, you always need to be prepared to loosen your grip. This is not only true of science, it should be true of all beliefs, but it is not easy. We are tribal and we like to feel that we belong. To belong often meets to be united by your beliefs and, even more so, united by hatred of those who contradict those beliefs.

We are all victims of our cognitive dissonance. Our desire to hold on to beliefs about the world means that people often follow all manner of circuitous routes of thought in order to preserve their beliefs, even when they become increasingly preposterous. With the dominance of social media, there is now a perpetually pumping plumbing system that sprays out opinions twenty-four hours a day. We are never more than two seconds away from an utterly bizarre opinion that is rabidly held.

Sitting in rooms with physicists, I sometimes observe their perplexed faces as they try to understand the erratic and destructive beliefs and decision-making of other humans. ‘Haven’t they seen the statistics and the graphs?’ they wonder. For some, this is why they were drawn to physics. Even in a probabilistic universe, the paths of electrons are easier to predict than the actions of other human beings. Evidence can often play a very minor part in why we believe what we believe, so when the physicist tries to refute your ideology with years of carefully accumulated evidence, you can shrug it off and return to your invisible leprechaun farm.

I can also find myself frustrated by scientists. It seems to me there are some who consider that they have such control over their own minds that the pure evidence they have discovered means they would never fall victim to any cognitive dissonance. I have also grown to dislike those sneering T-shirt slogans or memes that say, ‘Science doesn’t care about your opinions’, as if by being a scientist, their feelings and biases are always usurped by their superior brains, which can manage to neatly box their emotions, only occasionally releasing them for birthdays, funerals and screenings of The Shawshank Redemption.

It goes both ways. When scientists are particularly attached to an idea, evidence may not be enough; and again, though they might deny this, emotion may play its part.

Fred Hoyle was a brilliant scientist. With US physicist Willy Fowler, he demonstrated that all the elements of our world originated from inside stars and were then projected through the universe via stellar explosions. The romance of us being made from star-stuff was confirmed by his work. It provided us with a beautiful story, offering us another sense of connection with the whole universe. Pondering on the journey that the atoms that make up you and me have made throughout history is meditation time well spent. Fred Hoyle is probably best known, though, as the astronomer who, despite increasing evidence, would not accept the Big Bang theory. He continued to prefer his steady-state theory. Astrophysicist Chris Lintott thinks that what lay at the heart of Fred Hoyle’s thinking wasn’t a scientific dispute; it was his hope and desire that the universe would go on for ever. After all, when the universe ends, physics ends, too. ‘Hoyle realized very early that if you have a universe that’s changing, that implies not just that there’s a beginning but that there’s an end, even if it expands for ever. And so his steady-state theory was a way of getting away with that, because you’re continually producing new raw material from which you can keep making stars and planets and astronomers,’ Chris explains. When considering scepticism, it is important to realize that the clear thinking of scientists may also be polluted with emotional attachment and egotism.

With curiosity, though, comes doubt; and if your doubt remains active, you may become marked as a sceptic – something often confused with being a cynic. The sceptic, like the atheist, can be seen as a killjoy. There you are, having all the fun of believing that the Earth is flat, or shunning a potentially lifesaving vaccine because a Hollywood celebrity made a five-minute YouTube film that was informed by someone else’s five-minute YouTube film, which was in turn informed by a YouTube film by a vitamin-pill salesman (and the infinite regress of misinformation goes on), and some sceptic comes along and suggests that it might all be a bit more complicated than that. The importance of doubt working in tandem with science is potentially life-saving. Some may say at this point, ‘But isn’t rejecting the Earth being a sphere, and rejecting vaccines, scepticism?’ And I would suggest that you try arguing with the people who hold these opinions. Their beliefs require a rejection of a great deal of evidence, often based on suspicion or paranoia and the unproven ideas of secret cabals, not really offering testable alternative realities or ideas.

There is a reason why fundamentalist religious and political systems often ban books. It’s because they can be full of ideas and possibilities that can reframe the world in a way counter to that set out by those systems. Books are pliers for the barbed wire with which a dictator wishes to encircle someone’s mind. Once, in Canberra, I spoke to a man who had been brought up in a fundamentalist Christian commune. While other teenagers in Australia may have been hiding creased pornography under their mattress, he had a book of essays by the philosopher A. C. Grayling. This was the key to his rebellion.

A book brought me to sceptical thinking, too, though I did not have to hide it under the mattress, which was fortunate, as I was sleeping on a futon with a very thin mattress and the sharpness of a book corner could have caused spinal damage. In Sceptical Essays, Bertrand Russell wrote that scepticism will diminish the incomes of clairvoyants, bookmakers and bishops. He tells the story of Pyrrho, the first Greek sceptic philosopher, who considered that ‘we never know enough to be sure that one course of action is wiser than another’. When Pyrrho saw his philosophy teacher with his head stuck in a ditch, he didn’t pull him out, as he didn’t think he had enough information to be certain that his teacher didn’t want to have his head stuck in a ditch. After others pulled the teacher’s head out, his teacher congratulated Pyrrho for correctly interpreting his philosophy, even if it did lead to him having his head stuck in a ditch for longer than it needed to be. (We are never told how he got his head stuck in a ditch in the first place, and I am not sure I would hold someone’s teachings in such high regard if they were the sort of person who found themselves in such a position. I am also not sure he would have congratulated Pyrrho quite so heartily if no one else had pulled his head out of the ditch. By the third day, say, even the most stoical of stoics could have become fed up of having his head stuck in a ditch, especially if goats were beginning to sniff around.)

‘They swim. The mark of Satan is upon them. They must hang’

My interest in scepticism grew before my interest in science was rekindled. It really took hold at the witch trials, or at least the site of witch trials, both historical and fictional.

It was the story of the small English town of Lavenham that sparked it all off for me. Its connection to witch trials made it a good place to start questioning why we believe what we believe. Here was one of the locations where the vagaries of nature – whether crop failure or erectile dysfunction – had led to women being burnt at the stake if they failed to do the proper thing and demonstrate their propriety by drowning in a river.*** Women from Lavenham were tried as witches, but the most famous Lavenham witch trials were fictional, in the film-cult classic Witchfinder General, the final film of the far-too-short life and career of enfant terrible film director Michael Reeves,* with Vincent Price playing Matthew Hopkins in the title role.

After wandering around the Lavenham square where Price’s Hopkins set fire to Maggie Kimberly, I went into an antique shop, looking for a Toby jug of interest or a framed cigarette card of Boris Karloff. Instead I found a second-hand copy of James Randi’s Psychic Investigator, the book of the TV series in which the conjuror and escapologist tests the claims of spiritualists, dowsers, telepaths and suchlike.

My first attraction to these stories was as low-hanging fruit for stand-up comedy routines. I was particularly keen on the toe-curling tales of floundering psychic mediums struggling for any sort of ghost that might connect with their audience. My favourite was the medium who stood onstage and announced that the ghost who had sat down beside him liked cheese-andpickle sandwiches – one of Britain’s most popular sandwiches, especially among the generation that were most likely to have died recently, and likely to be popular with his living audience too. Somehow, in a room of more than 500 people, none had a deceased relative who was remembered for being fond of this highly popular sandwich – surely a statistical aberration. Labouring over the details of the snack, as if the audience might have forgotten what a sandwich was, the increasingly flustered and irritated psychic still found no takers. Finally a sheepish man at the back recalled that his father loved cheese, but that he was not allowed to eat it. This was the spirit connection that the medium now said he was looking for. Due to poor communication between the living and the dead, ‘lactose-intolerant’ was translated as ‘cheese and pickle’.

Though I enjoyed the laughter that I could generate from such stories, they made me angry, too. The dairy-product-confused psychic could make as many cock-ups as he liked and still play bigger rooms than me. Each preposterous failure would be forgiven; every minor hit was a miraculous success. Fortunately, with even more bizarre and clearly preposterous theories making it into the twenty-first-century mainstream, I barely have time to be utterly appalled by such ghost-whisperers.

Some of James Randi’s most damning investigations involved faith healers, a similar scam to psychic mediums, although with the ill being preyed upon, rather than the bereaved being mocked. One of his most famous cases from the late 1970s concerned Peter Popoff, a minister who was stunningly accurate in his healing powers. God would tell him the full names and addresses of the sickly people in his audience, and exactly what was wrong with them. He would then heal them with his touch and watch the donations flood in. Once scrutinized by Randi, it became apparent that this connection to God was via an earpiece that broadcast his wife’s specific instructions, based on information that the audience had volunteered on entry. His gift from God was actually a purchase from a high-end electrical shop. The scam was revealed on Johnny Carson’s The Tonight Show, one of the USA’s biggest TV shows. The revelations destroyed the Popoff ministry and he never worked again… … is what I wish I could write. Sadly, years later the Popoff ministries continue to be active, now under his slogan ‘Dream Bigger’. Popoff certainly doesn’t want an audience that is too awake – the more docile and close to a dream state, the better. On his donation page he reminds you to donate big, because that is what 2 Corinthians 9:6 tells you to do.1 God has monetized his miracles. On Popoff’s Miracle Spring Water page, you are reminded: ‘DO NOT INGEST THE MIRACLE SPRING WATER’. Overly powerful miracles can prove toxic and cause diarrhoea.

When I interviewed Randi about the Popoff investigation forty years on, it was clear that he was still disgusted and disturbed that Popoff could abuse and manipulate people. His voice cracked when he recalled some of the abusive, dismissive and derogatory language that was used to describe the people to whom Popoff’s wife was leading him. Not only were they fleecing these people, they were laughing at them as they did so.

Some people may defend faith healing, suggesting that it could have some place in people’s physical well-being. If someone is persuaded that their pain can be alleviated through the love of Jesus, it might act as a placebo; but when it comes to cancer, HIV or numerous other diseases, positive thinking alone will not work.