Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

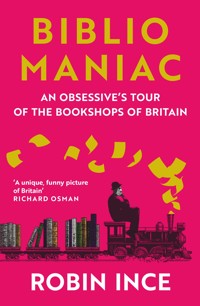

***A Waterstones Best Books of 2022 pick*** 'A unique, funny picture of Britain... A love letter to bookshops and the vagaries of public transport.' Richard Osman 'Ince's love of books is infectious.' 'Books of the Year', Independent Why play to 12,000 people when you can play to 12? In Autumn 2021, Robin Ince's stadium tour with Professor Brian Cox was postponed due to the pandemic. Rather than do nothing, he decided instead to go on a tour of over a hundred bookshops in the UK, from Wigtown to Penzance; from Swansea to Margate. Packed with witty anecdotes and tall tales, Bibliomaniac takes the reader on a journey across Britain as Robin explores his lifelong love of bookshops and books - and also tries to find out just why he can never have enough of them. It is the story of an addiction and a romance, and also of an occasional points failure just outside Oxenholme.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 427

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

BIBLIOMANIAC

Robin Ince is co-presenter of the award-winning BBC Radio 4 show and podcast, The Infinite Monkey Cage. He has toured his award-winning stand-up across the world, both solo and with his radio double-act partner, Professor Brian Cox. His other books include I’m a Joke and So Are You and The Importance of Being Interested.

‘You may think you have a book problem but, as likely as not, comedian Ince’s will dwarf it... There’s some nice travel writing here as he wends his way from Wigtown to Penzance, along with cosy anecdotes about the folk he encounters and some madcap tangents, invariably prompted by his eclectic reading habits.’ Observer

‘I like books and if you’re reading this you almost certainly like books too. But Robin Ince really, really, really likes books, and this tome takes us on a whirlwind adventure around Britain’s bookshops and inside the head of a bibliomaniac who also happens to be a fine travel writer and generous raconteur. (Includes the funniest line about Margaret Rutherford ever written, unless the lawyers took it out.)’ Ian Rankin

‘Robin Ince is a book-lover’s book-lover, a man who responded to publishing his last volume by visiting over 100 bookshops in 100 days. He is a reader without prejudice, a lover of every type of fiction and non-fiction, able to find something that interests him in everything: the sure sign of a man with a curious mind. You need Robin Ince in your life; you need his book on your shelves.’ Natalie Haynes

By the same author

Robin Ince’s Bad Book Club

I’m a Joke and So Are You

The Importance of Being Interested

With Brian Cox and Alexandra Feachem

The Infinite Monkey Cage – How to Build a Universe

BIBLIOMANIAC

An Obsessive’s Tour of theBookshops of Britain

Robin Ince

First published in hardback in Great Britain in 2022 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

This paperback edition first published in Great Britain in 2023 by Atlantic Books.

Copyright © Robin Ince, 2022, 2023

Illustrations © Natalie Kay-Thatcher, 2022

The moral right of Robin Ince to be identifi ed as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

Every eff ort has been made to trace or contact all copyright-holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Paperback ISBN: 978-1-83895-771-1

E-book ISBN: 978-1-83895-770-4

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

Contents

Preface to the Paperback Edition

Tsundoku: An Introduction

1 Out of Lockdown and Into the Wicker ManWigtown to Laugharne

2 It All Began at the End of the WorldChorleywood to Bristol

3 I Only Play in the Finest Freezer CabinetsSidmouth to Birmingham

4 Pity the LlamaOxford to Norwich

5 Mermaids and Mermonks?Okehampton to Shoreham

6 What is Avuncular Knitwear?Margate to Southwold

7 Where Orwell Ate His ChipsSouthwold to Leeds

8 Black Holes Drowned Out by the Bells of GodChippenham to London

9 Hurricanes at the Benighted InnMalvern to Malton

10 Important Lessons from a PorpoiseEdinburgh to Hull

11 From the End of the Line to the Girl Guides’ HallHull to Hungerford

Afterword

Notes

Thank You…

‘Last Night’

Index of Bookshops

Index of Books

Dedicated to all the bibliomaniacs, all of those who are never happier than when in a library or a bookshop and especially to my friend Katherine, formerly KP, who has always been the most kind and curious person and has led me to many wonderful books.

And always to Nicki.

And always to Archie.

Preface to the Paperback Edition

Iam happy to say that my father really enjoyed Bibliomaniac. It was his favourite of the books I have written.

This book is about him because it was his passion for books that put a spell on me and led to my love of books too. It was a vital connection between us.

Sadly, he will not read my next book. He died a few months after Bibliomaniac was published.

The last time he left his house was to see me talking at the Chorleywood Bookshop. He sat in a comfy chair in the front row and when the owner introduced me, telling the audience that I had recently been awarded Author of the Year by the Booksellers Association, my father loudly remarked, ‘I don’t know why!’ A typical move by him. He was proud of his children, but public displays made him embarrassed.

As my father became less mobile in his last years, I became his surrogate browser of the outside world. On tour, I’d always be seeking out books that I thought would delight him, which was always a good excuse for a phone call. The last book I delivered to him was a biography of the actor Robert Donat, whose films we watched together many times, in particular The 39 Steps and Goodbye, Mr Chips.

Returning from the Laugharne festival, another weekend of authors and book browsing with my bookseller friend Jeff, I went to stay over with my dad. The next morning, I was woken up by him calling for help. Entering his bedroom, I think he was worried he was having a heart attack. Actually, the pain in his chest was pneumonia, but we didn’t know that then. I rubbed some cooling gel on his back and, when my sister returned, I popped into London for a book launch at John Sandoe Books. I am not very good at such social occasions, but this was for Sarah Bakewell, an author I admire greatly, and my dad always enjoyed stories of these literary events he could no longer take part in. Rather than return to his home after the wine and cheese straws, I went straight to Stoke Mandeville Hospital where he lay in a corridor.

In between my father’s bouts of wakefulness, I read a copy of Raymond Chandler’s The Big Sleep with a particularly vivid cover of a corpse in some orchids.* By dawn, my dad’s hypnagogic dreams and his stretcher-bed reality had become confused. He told me, ‘It was roast pheasant last night and I think it will be again today.’ I suggested it was more likely to be an egg and cress sandwich and yoghurt.

Over the first three days, the prognosis was neither good nor bad, but he was 92 and a body at war in its tenth decade is often short of supplies. I popped down to Devon for a few days with my wife’s family, but within twelve hours of arriving, I was summoned back.

For the last twenty-four hours, his consciousness had faded and so we sat around his hospital bed and read from his favourite book, Tarka the Otter. It was 1 April and we hoped that he might make it to the 2nd as Fool’s Day as the day of death wouldn’t suit him. He made it past midnight and on to lunchtime, and then the him-ness of him was gone.

The reading of books together, of Tarka, and The Hobbit, and the mid-1940s novelization of a favourite film, Powell and Pressburger’s A Matter of Life and Death, created a sense of ritual over this last few hours. His birthday present arrived too late to be read, another 1940s novelization of a Powell and Pressburger film, I Know Where I’m Going!

In his last two years, he kept telling me that he had decided to stop ordering new books as he knew there just wasn’t time to read the many he was surrounded by, but he was a bibliomaniac too. At least twice a week when I went to check the post, there would be a brown paper parcel for me with a new treat inside. His last purchase was 103 Not Out from the lovely little independent publisher The Fleece Press; it’s a book about the 103 Royal Mail stamps designed by David Gentleman, with an unfranked copy of every one of those stamps within its pages.

I am writing this while taking a break from sorting dad’s books. It is taking time because every one must be scrutinized for things that may lie within. I pulled out a copy of a hefty historical romance in the Angélique series. I believe they were very popular in the 1950s and generally involved the eponymous young blonde woman ending up entangled with untrustworthy dukes. She was reaching higher this time – it was Angélique and the King. I thought it would make the charity donations pile, but when I opened it, handwritten on the first page was: ‘Pam, for the best 365 days of my life so far, Nigel’. This was his first wedding anniversary, the paper anniversary, gift to my mum, and so it stays. Within two days, I had already collected 74 bookmarks and there will be many more to find, some leather ones with fading cathedrals embossed on them, occasional ones with tassels, and many cardboard page reminders from the charities he supported. There is a story in the bookmarks before we even start scanning our eyes across the books. The rituals of his death and the memories of his life are often bound, some paperback, some hardback.

When I was at Westwood Books recently, we talked of the things that fall from books. Once, they discovered that a longforgotten bookmark inside a volume of botany was a cheque from Charles Darwin. They also received many books that had once been owned by Nicole, a young woman who died far too soon. In every book, she wrote where she bought it from, then on chapter one she wrote where she was when she began the story and on the final page where she was when it was finished, and sometimes a little precis of her experience between the pages too. How delightful that she left some of herself behind. Leave some of yourself in this book too. When you pass it on, I hope there is a bus ticket or four-leaf clover within. My friend Jeff told of how sometimes, when asked to sort through the books of avid collectors who have died, he is friends with them by the end of the process, even though he never knew the person in life.

Between the lines of Bibliomaniac is the story of how my father made me.

Robin Ince, July 2023

Tsundoku: An Introduction

Let’s start with a battle cry, but quietly, just in case you are in the library.

I don’t retreat into books, I advance out of them. I go into a bookshop with one fascination and come out with five more. I always need another book. I love their potential.

I love the moment of pulling an intriguing title from a shelf and exploring what’s within, perhaps E. C. Cawte’s Ritual Animal Disguise or Julian Symons’s The 31st of February – ‘an ugly vortex of horror at the limit of human tension’. On a perfect day I walk out of the bookshop with a canvas bag of known and unknown delights and find a tearoom, where I revel in each new purchase while tucking into a piece of Victoria sponge.

This is my holy time. Here is transcendence.

I have shaken off almost all of my other addictions, but never my insatiable desire for more and more books.

Books about William Blake.

Books about climate change.

Books about spider goats.

Books about the evolution of flight.

Books about avant-garde performance artists.

Books about Princess Margaret.*

Books about satanic transport cafés.

Those just happen to be the ones that have come home with me today.

In The Nature of Happiness Desmond Morris wrote, ‘One of my great joys is going on a book-hunt. Finding a rare book I desperately want after a long search, acquiring it and carrying it home with me, is a symbolic equivalent of a hunt for prey.’

Being both a vegetarian and clumsy with a spear, I find this form of being a noble huntsman suits me. As a male who is far down the Greek alphabet when it comes to my masculinity, my delusions of warrior status when searching for a Shirley Jackson rarity ennoble me.

I have many gazelles mounted on my bookshelves. I do not buy books for their rarity or potential profit, I buy them because I want them, although there can be an extra frisson of excitement when you find you have purchased a rare bargain.

Browsing a thirty-pence bookstall, I once saw a 1921 hardback copy of Relativity: The Special and the General Theory – A Popular Exposition by Albert Einstein. I had a modern copy already, but I thought it would be nice to have an old edition, an artefact that enabled me to contemplate who had been in these pages before me. It was a sixth impression, so I imagined there were many copies out there and it would be worth only a couple of quid. Later I found out it could be worth more than £300. To make my thirty-pence purchase even better, inside was a ‘bookmark’, an old Methuen marketing ad for The Warlord of Mars by Edgar Rice Burroughs: ‘Only the man who created TARZAN, the ape-man, could have written these amazing stories.’ Book-hunting is big game.

My entire life and my career have been shaped by books and browsing. It was my delight in finding such oddities that led to me putting on a series of comedy shows where, with accordion accompaniment, I would read from gory pulp horrors, Mills & Boon classics of love with lighthouse-keepers, and lifestyle advice books such as What Would Jesus Eat? and How to Marry the Man of Your Choice.

This led on to a long-running podcast series about books and authors with my friend Josie Long, Josie and Robin’s Book Shambles, and then to the science-book-based shows that in turn led to me making the long-running podcast series The Infinite Monkey Cage with Professor Brian Cox.

Books define me. They are even the reason I stopped drinking heavily. I realized that if I drank too much after a gig, the reading on the late train home was blurry and so became wasted time. In my finite existence I was missing out on comprehension due to intoxication, so I pretty much gave up.

Books are the reason that Brian Cox did not kill me when he first took me onto the moors for a harsh exercise regime together. He had already been training for three years; I hadn’t swung a kettlebell in my life. On our first exercise session we took some heavy ropes and other weights. Brian looked as surprised as a physicist can, when I was still standing an hour later. I was even able to walk a little. It was as if I had compounded the physical laws of the universe and walked through two doors at once.

On the walk back I explained that, although I take no formal exercise, I walk miles on every tour I do and, as I stop in every bookshop I see, the weight that I carry increases on an hourly basis. Sometimes I have to buy books just to make sure the weight is equal on both sides. The Fyodor Dostoyevsky fitness regime.

My life is summed up by the Japanese word Tsundoku – allowing your home to become overrun by unread books (and still continuing to buy more).

Shelf space ran out long ago. However high and teetering the piles become, my bibliomania is unstoppable. I cannot buy only one book. It is no books or many books, though it is never no books. I can walk by a bookshop and my mind will tell me, ‘Just keep on walking.’ Then another corner of my mind says, ‘Hang on, do you remember there is that one book you need for that project you are working on. Why not pop in and see if they have that one book and then pop straight out?’ And I’m gone, like the addict I am.

Are these books useful? Perhaps most painfully, I have at least ten books about decluttering your life for a happier future, strewn around my house.

I want to know about everything, so I know about nothing.

At one stage my house became so swamped with books that I donated more than 1,000 of them to Leicester Prison* and got rid of a further 5,000 more to charities. And yet I know that my house is still overrun, always on the cusp of being justifiable grounds for a divorce.

I am sometimes asked how I read so much. I commit the cardinal sin among some bookish people: I leave books unfinished. I hop in and out of them, grabbing an anecdote, an idea or a philosophy and then putting them on the teetering ‘to be continued’ pile.

Whether they are useful or not, I am in love with books. I sleep with many piled on my bed and sometimes one that has gently fallen on my face, as exhaustion overcomes my ability to travel any further. In my dreams I run riot in a chaotic Borgesian library. Someone once told me that my lust for books meant I had jumped from bibliophile to bibliosexual, but I think I prefer bibliomaniac.

I was lucky to grow up in a house filled with books. Books never meant boredom. If you think books are boring (and I presume you do not, or you wouldn’t be reading this book about books, or be in a bookshop weighing up whether you want it or not), then it’s my view that you simply haven’t met the right book yet.

From an early age I would go with my dad to book fairs, where he would search for works by Henry Williamson, best known for Tarka the Otter, and Evelyn Waugh, who enjoyed depriving his children of bananas during wartime (I’ll tell you more about that later). I remember seeing the Labour politician Michael Foot scouting for Byronic volumes, and once the Scottish eccentric and poet Ivor Cutler asking for rarities by Maurice Sendak, most famous for Where the Wild Things Are and In the Night Kitchen. On trips to central London with my dad I was usually the youngest child in the bookshops of Charing Cross Road and Cecil Court, looking intense in my NHS specs.

In the middle of 2021 I found myself at a loose end. I was meant to be going on tour with Professor Brian Cox, but the worries of playing arenas in a time of uncertain Covid variants meant that we decided to postpone it.

I had an idea. I had a new book coming out, The Importance of Being Interested, and it was a celebration of curiosity. It was a book that grew from my childhood immersion in The How and Why Wonder Book of Time, The Big Activity Book of Prehistoric Mammals and Usborne World of the Future: Star Travel, all of which eventually led to being able to read science books with hardly any pictures at all. I decided that I should go to where so many of my fascinations begin: the bookshop.

To fill the gap where the tour should have been, I would visit at least 100 bookshops across the United Kingdom. I swapped playing to 12,000 people in Manchester Arena for playing to twelve people in the Margate Bookshop.

Visiting all these independent shops highlighted to me exactly why the independent bookshop is such a vital part of the high street. These shops and the people who run them are the gatekeepers to stories we never knew we wanted to read; to ideas that might increase our happiness or help us deal with our sadness; to places that our mind never knew it might go. You can always have a proper conversation in a bookshop. You can skip ‘Looks like the weather’s on the turn’ or ‘Parking around here gets worse and worse’ and skip straight to ‘Have you read Klara and the Sun yet?’ or ‘There is a fascinating theory about self-driving cars and artificial intelligence – can you remember who’s just written a book about it?’

The bookshops have found out something rather useful about me too, and that is that I am a very profitable person to have along for an event. Sure, it might mean that they sell a few more copies of my book, but even if they don’t, they know their profits will go up because I’ll go away with a caseload of other people’s books. A simple afternoon-signing in Letchworth, England’s first Garden City, led to me buying The Last Cannibals – ‘she’s a charmer, but she’s a Cannibal’; The Dharma Bums – ‘fighting, drinking, scorning convention, making wild love – zany antics of America’s young Beats in their mad search for kicks’; and The Furies – ‘now comes cosmic retribution – giant wasps’; as well as Only Lovers Left Alive, I Can See You But You Can’t See Me, Lady Cynthia Asquith’s The Second Ghost Book and Devil’s Peak by Brian Ball – ‘Stranded in a High Peak transport café during a freak snowstorm, Jerry Howard finds himself in a vortex of Satanism.’

I think I love books even more than I love reading. Their company means there is always the possibility of something to be discovered, waiting for me between the covers, which hasn’t even entered my imagination yet. A small but pleasing change in my reality is waiting on every shelf.

I know that I have a predilection towards melancholy, social anxiety and self-loathing, and books form a great part of my prescription medication. When I say that books are my drugs, I don’t mean that in a throwaway manner; they really do calm me, they really do shut off some of the voices for a while.

They really do take me out of time.

Books are not merely my escape, but an opportunity to explore the world – my chance to get the voices from the page to drown the voices in my head; the place to live in other people’s dreamscapes. I am too anxious for some of the hallucinogens that my confident friends experiment with, so my trips are fuelled by turning pages.

Like most of my few friends, I am gregarious, but also antisocial, living in perpetual fear of judgement. I can spend time listening to the voices in books without worrying what those voices think of me.

This book is the story of an addiction and a romance – and of an occasional points failure, just outside Oxenholme Lake District station.

Footnote to explain any later narrative confusion

Shortly before this adventure began I had a lengthy conversation with an expert in neurodivergence who had followed my career and social-media accounts. After a three-hour conversation he told me, ‘Basically, every answer you have given points very much to you being ADHD.’

This is something that audiences have been telling me for years. Regularly in the theatre bars after a show I am approached by a puzzled-looking person who says, ‘My husband and I have made notes of the seventeen stories that you started but never finished, and we would like you to tell us the ending of at least five of them, to get some sense of closure before we leave.’ Some of these stories I have no recall of at all.

I wondered what my wife would make of this diagnosis. Would it worry her? I once asked her and she said, ‘That would be wonderful, because I’ve always thought you were bipolar.’

Anyway, the reason I tell you this is because this may be a more tangential book than you are used to. It is a story of many of the thoughts of books that crossed my mind as I crossed the UK on this rather hectic book tour. It may be chaotic, but it might make sense between the sentences.

* Actually, I only have one book about Princess Margaret, but it is very good.

* To any judge reading this: please show mercy on me and send me to the prison where I sent my books ahead of me.

CHAPTER 1

Out of Lockdown and into the Wicker Man

Wigtown to Laugharne

I am unable to do things in moderation.

I thought it would be enjoyable to visit some independent bookshops when my book came out. ‘Some’ started out as half a dozen or so, then rose to twenty, was briefly fifty and then a gimlet-eyed lunatic swept his hand across the map and said with piratical glee, ‘If it’s gonna be fifty, it might as well be one hundred!’

After eighteen months of being rendered stationary by a virus, eighteen months in my attic, eighteen months in my head, I was now going to go everywhere.

I put the call out on social media: ‘Are you, or do you know of, an independent bookshop that I should visit in the UK?’

I made a spreadsheet. By ‘spreadsheet’ I mean I grabbed a stack of Post-it notes any time I saw a reply and scribbled details haphazardly and illegibly. A lavish map of scraps and scrawls was soon a tour, and my spreadsheets were a Dadaist triumph – somehow both pointless and informative.

At 111 events, I ran out of days. I reached the point where I would have needed to manipulate spacetime to squeeze in any more destinations, and I’ve been warned to avoid doing that as it can have ramifications, in terms of changing the outcome of world wars and plagues.

I knew my wife would be happy to see the back of me. I have been a perpetually travelling performer, so it was perplexing for her to see me every morning during the pandemic. Eventually I grew a beard, so that at least she could think I was someone else.

If you travel, you probably know that the further you are from home, the more you are loved by those you’ve left behind. The distance erases your imperfections. I made a graph (in my head).

When I was in Wellington, New Zealand, I was longed for.

When I was in Boston, USA, I was missed.

When I was in Aberdeen, Scotland, I was asked how much longer I would be away.

When I was in Croydon, south London, I could hear the horror at my physical self returning. ‘Oh my God, he’ll be back in two hours, treading things into the carpet and moving the magazines!’

No one has been more loved than Neil Armstrong on 20 July 1969. ‘Oh, Neil, you’re so far away, I love you even further than to the Moon and back.’ Two weeks later… ‘I see that someone has left moondust all over the sofa.’

Before the bookshop tour, I had two festivals to warm up at.

First I would walk in the footsteps of Sergeant Howie, the doomed, virginal policeman sacrificed on a pagan island in hope of fruitfulness. I was off to Wigtown, Scotland’s book town, situated in the countryside where the original 1973 The Wicker Man was filmed.

I became fascinated by this film when I was eight years old because of Alan Frank’s Horror Movies. This was my first truly favourite book – a book of almost biblical importance to me. If there had been any ‘favourite’ book before then, it would have been Hamlyn’s Children’s Bible in Colour. I still fondly remember the violent illustrations of Abimelech being killed by a millstone dropped on his head and Absalom hanging in a tree branch.

The gore of horror-film books were only a small step forward from what The Bible had prepared me for. I used my birthday money to purchase Horror Movies and I would pore over the photographs and create feature films in my head from single shots of ravenous vampires – ‘Christopher Lee begins to feed’ – or cryogenically frozen Nazis – ‘Nazis on ice!’ The Wicker Man was represented by a single colour photograph of Edward Woodward horizontally viewing a hand of glory, the fingers fashioned into lit candles: ‘Left: Edward Woodward surveys his “bedside lamp” with horror in The Wicker Man (British Lion 1973).’

This book was educational in many ways, as it was how I learnt my left from my right. I knew my monsters before I knew which hand was which, so when the pages said, ‘Right: Karloff meets his mate in Bride of Frankenstein’, and ‘Left: Michael Hordern stakes a burning cross through Baron Zorn’s heart’, I began to get the hang of directional instructions.

Wigtown

Wigtown is Scotland’s answer to Hay-on-Wye. Like Hay-on-Wye, it has many bookshops; also like Hay-on-Wye, it is some distance from a railway station. This means that you never know which author you might be sharing a lengthy car journey with. Last time I went it was with the former Conservative politician Kenneth Baker, one of Maggie Thatcher’s Cabinet, and famously represented on Spitting Image by a rubbery puppet of a slimy slug. The journey was perfectly fine, but my head kept reminding me that this pleasant old man was someone I had once marched against on the streets of London. I recalled the despicable Clause 28 brought in by Baker’s sneeringly homophobic government – a piece of legislation aimed at preventing the ‘promotion of homosexuality in schools’, which really meant the mentioning of homosexuality in schools. The propaganda would have been hilarious, had it not been so dehumanizing.

One of my most-prized second-hand book finds over the years is Jenny Lives with Eric and Martin. Kenneth Baker condemned it, perhaps as part of what he declared was ‘grossly offensive homosexual propaganda’ that was placed in libraries by ‘left-wing authorities’.1Jenny Lives with Eric and Martin was centre-stage in the media’s stirring-up in the 1980s of a homosexual panic that had been elevated by the AIDS crisis. It was ugly, brutal and degrading. It was also preposterous and infantile. The Sun bellowed, ‘VILE BOOK IN SCHOOLS’ of Jenny Lives with Eric and Martin. First, it wasn’t available in schools – there was one copy in the Inner London Education Authority’s library; and second, this was no Marquis de Sade. The book is about Jenny’s dad, and his male partner, looking after her. Sordid pictures include a man with clothes pegs in his mouth hanging out the washing; the three of them licking ice-lollies; and Jenny sitting in a go-kart. At the back of the book is a charmingly simple cartoon with three stick-people.

In the book Fred tells Bill that he loves him. A woman with a handbag and hat overhears them talking about moving in together. She is all exclamation marks: ‘Oh no! What is this! Two men cannot live together! It is very wrong!’ She explains that her husband would never kiss another man. Fortuitously, at that moment her pipe-smoking partner appears.

‘Now that is not quite right, dear. When I was young I was in love with a man and we lived together. But then I met you and it was you I loved most. And you loved me most. So we moved in together and got married.’ He explains that it can never be wrong to live with someone you are fond of, and she agrees and they all happily wave bye-bye to each other.

If only it was always that easy.

To get to Wigtown, I first had to get from London to Dumfries. After months of solitude, a return to the rails was daunting. I decided I would spend most of the journeysto-come in the vestibule, away from any mask-less hacking coughers. Even in plague-free days, I am a vestibule kind of guy.

The vestibule smelt far less of salt-and-vinegar crisps and broken wind than the main carriage. Standing for the three hours to Carlisle, I consoled myself by finding a very relevant article by an evolutionary biologist about how the invention of the chair was detrimental to our spines.* Somewhere north of Preston, the train cleaner came to empty the overflowing bin. He was a little older than me and looked like the kind of person who’d been in a post-punk band for a while, which it turns out he was, although they never got signed. As he grappled with the overstuffed bin, bruised grapes rolled out like a scabby victory from a fruit machine. He swore at each slippery juice-bauble and turned to me: ‘Come the revolution…’

By this point I was reading Getting the Joke by Oliver Double and, by coincidence or synchronicity, I had reached a passage about Bertolt Brecht’s ‘Red Grape’ theatre group. Here were grapes and revolutions on the page and in the air, and on the floor of the vestibule. I mentioned this to the cleaner and at first he looked understandably puzzled. This is a familiar reaction. I’ve come to realize, over many years, that my opening conversational gambits have a habit of being peculiar.

Then, however, rather than him running away screaming, the conversation broke into talk about bands like the Lotus Eaters, The Redskins and Billy Bragg as well as the joy of going to a record shop on Saturdays and hoping you had enough money to buy an album. The cleaner looked as if he was having a pretty shitty day, but after our five minutes of early 1980s nostalgia, taking himself back to his own post-punk band days, he went away whistling ‘The First Picture of You’ (the Lotus Eaters’ number-fifteen hit of 1983). I was happier too. You get a better class of conversation in the vestibule. Thanks to my nose being in a book, we could talk.

There were no former Education Secretaries on the way to Wigtown this time. The journey would be with the chemist and author Kathryn Harkup. Fortunately I had recently given her publisher a positive quote for her book about the elements: ‘Brimful of captivating stories and revelations’. I find giving quotes for books tricky. You need to be brief, but not trite. Sometimes you will smugly compose a twoline triumph of concise and informative wit, but when the book comes out, you’ll see that you have been reduced to ‘a triumph’ or ‘great read’ or ‘eloquent crab murders’.

I have attempted to dissuade people from asking for quotes, by explaining that if my name on a book sold lots of books, then the books written by me would sell a lot more, but then I realize they have already had dozens of knock-backs from reputable people and I am merely the last resort. (Who did I manage to persuade to blurb me on the back of this? Did it persuade you?)

Wigtown is quiet when we arrive, the day’s bibliophiles having departed for the day. My evening reading is Wicker Man-related. When I can, I try to attach a local flavour to my reading events. Ritual was a novel written by David Pinner, published in 1967, and was supposedly the inspiration for the film, although there is some debate on how much of an influence Ritual truly was.

I open the book to a page where the policeman is being tempted by a naked woman in the room next door – a bit like the scene from the film where Britt Ekland (and her body-double for all the shots of her bottom) attempts to tempt Sergeant Howie. ‘The left breast was fractionally larger than its sister. It was Anna’s favourite. She flexed it towards the wall.’

There are definitely differences; for instance, Edward Woodward doesn’t end up licking the wallpaper. ‘With disgust, David realized he was licking faded dancer off the wallpaper. The dancer was painted yellow and purple. That is, before the licking began.’

Fortunately, there is only silence from the occupant of the room next door to me, and my flock wallpaper remains unlicked.

I am up early to browse. I don’t want anyone getting first to a treat that I deserve.

In bookshops I suspiciously eye other customers, profiling them in case I think they may be after the same goodies as me, wondering if they have deliberately put the best books back in the shelves the wrong way round, so that I’ll miss them. There are some shrewd movers among the browsers.

In every town I visit, I have the pointless mental talent of being able to remember all the books I have bought there before – a very niche mystery memory act.

Today I recall from Wigtown the annoyingly oversized book I once bought that didn’t fit into any form of carrier bag, so I had to drag it around, like a book-lover with a Sisyphus curse. It was called The Home Planet and was full of beautiful images of Earth taken from space, with comments from astronauts. I had never seen it before, yet now I notice it in bookshops almost daily.

I also bought the considerably lighter Reed All About Me, the autobiography of the famously boozy, pugilistic actor Oliver Reed. On the front cover he simmers in a promotional shot from The Three Musketeers. On the back cover he stands in denim with his hand thrust down his trousers. I am not sure if the front and back are meant to be some kind of visual pun on him being a swordsman of two kinds, but I imagine I am putting more thought into it than the fast-buck publisher Hodder & Stoughton did in 1981. ‘I was covered in custard and bleeding badly from a rather large cut in my mouth’ gives you the broad gist of the style of his anecdotes, as does ‘Some of the nuns got carried away.’

I start my morning on this trip in The Bookshop, Scotland’s largest bookshop. It is a whole house turned into one. It reminds me of the sadly-no-more Cottage Bookshop in Penn, an inspiration for Terry Pratchett’s ‘L-space’ in the Discworld series. The Cottage Bookshop was one of the bookshops that shaped my youth, with its tightly packed shelves placed closely together – a cricked neck guaranteed – and some irresistible prices. It was here that I bought vintage James Bond annuals (not so vintage then), books on the mysteries of the world by Colin Wilson, and many Perry Rhodan science-fiction books, all of which remained unread, but looked lovely on my prepubescent sciencefiction shelf.

The owner used to have an attic room where he kept his priciest books (not his mad first wife): £5 and over. I would sometimes accompany my dad into this fabled world and the door would be locked behind you. Eventually the owner stopped opening up the attic of his precious things, as apparently some browsers had been urinating in his vases when their cries for release were unheard.

The Bookshop of Wigtown is an even more dangerous place during the festival as it also doubles as the green room, where performers and their entourage hang out before and after events. You get drunk and then you are allowed to browse. The first time I visited the Wigtown Book Festival I woke up the next morning with far too many books by David Icke about the reptilian takeover of humanity.

Opening Children of the Matrix, I was fascinated to see the name Schopenhauer spelt incorrectly in three ways on the first page. A bad start; or a good one for readers who believe the Illuminati have controlled the spelling of philosophers’ names for too long.

I also found a far more intriguing book on that drunken browse: Lewd; The Inquisition of Seth and Carolyn – ‘Being a real and true account of the assertion of the people’s ancient and just liberties in the trial of Seth Many and Carolyn Peck against the most arbitrary procedure of the court and its minions’. It is the story of a small commune in 1970 that was committed to the ‘usness’ of being. This ‘usness’ included naked events, and it was at this point that the authoritarians of America got involved. The book is a lengthy transcription of the court proceedings.

Q: What did you see about me? Would you describe the ‘me’ that you saw?’

A: You with no clothes on.

Q: Well, what parts of me did you see that made you feel that you should arrest me?

A: You with no clothes on.

Most of the proceedings move on in this way, describing the horror at witnessing the naked bodies of skinny hippies. This is typical of a certain kind of book that I buy, and of the alibis that I then make up for the necessity of having that book. First, I should make it clear that it is not the descriptions of nudity that draw me to such books, but rather that they describe something or someone so bizarre, unusual or unheard of that I imagine that one day it might be a lossleader for a show I will put on, perhaps about odd trials, or the counter-culture, or men with beards in bad Y-fronts. My shelves are packed with books that could form the basis for a show, or at least part of one. Every arcane title is an event waiting to happen.

When I get to the cashier and I see the mounting sums I am about to pay, I tot up in my head how many minutes onstage the book will need to appear in order to make its money back. Say I am doing a gig for £500 for forty minutes. That’s £12.50 a minute and so, technically, a book like Lewd (£6.50) has paid for itself if I read from it for thirty-two seconds. I would be rolling in it if I used it onstage for more than three minutes. Five years after buying it, it is still at zero minutes, but we’ll see.

Another example of such a book might be Dreams About HM The Queen (and Other Members of the Royal Family) by Brian Masters. This was £18, but it turned a profit after just one gig in Trowbridge. Brian collected other people’s dreams of the royal family, such as drinking sherry with the Queen when a man in a straw boater comes in with a bunch of bright new yellow pencils and declares himself the Keeper of the Queen’s Pencils; Princess Margaret removing biscuits from a digestive-delivering bicycle; a member of the Royal Ballet deciding to go to Mars for the Queen, because the Americans and Russians are hogging all the limelight. My favourite is probably the Queen Mother showing off about all the jam she has made, but continually dropping the jars, much to her consternation.

No nudity, reptilian or human, at The Bookshop today. My favourite purchase is a collection of photographs of the actor, dancer and choreographer Robert Helpmann (including one of him posing as Margaret Rutherford). I am a great admirer of Helpmann. For my generation he is probably best known as the Child Catcher in Chitty Chitty Bang Bang, but he was the most dynamic human, laden with chutzpah. He toured solo ballet shows across the mining towns of Australia, starred in Powell and Pressburger’s The Red Shoes, and was a fabulous wit. Famously, he played Oberon in a touring production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream that performed at a sports arena one night. His dressing room was a cricket umpire’s room. When Helpmann was given his half-hour call the stage manager heard no reply, so he entered the umpire’s room to see Helpmann standing on a chair that was stood on a table, with him balancing atop, holding a mirror by the one naked light bulb in the room and applying his intricate black-and-gold eye make-up. The stage manager asked if he was all right. ‘Yes, I’m fine,’ Helpmann replied, ‘but God knows how these umpires manage.’

I also bought Parker Tyler’s The Three Faces of the Film because of its chapters on ‘The Dream Amerika of Kafka and Chaplin’ and ‘Reality Into Dream Into Myth Into Charade Into Dollars’, which contains the phrase ‘a quasi-Pirandellian brand of illusionist realism’, which I aim to prise into conversations on a twice-weekly basis.

To keep my browsing eyes sharp, I gave them a rest and took a walk under the sky in between rain showers, and found the graves of the Wigtown Martyrs – two women, Margaret Maclauchlan and Margaret Wilson, who were murdered by dragoons during a period known as ‘the Killing Time’, a conflict between Presbyterian Covenanters and King Charles II and James II. A bookshop with a proximity to an interesting graveyard is a fine combination.

Eyes restored, I bought A Dictionary of Symptoms from The Book Corner. This will be invaluable for identifying the differences between fistula and papillomata, water brash and dyspepsia. There is something for all my hypochondria needs, and the yellowing pages of a 1970s manual, with a vague aroma of roll-ups, seems so much more trustworthy than the internet. Every vague rash can now be my imminent Armageddon.

Having been almost parsimonious in my book purchases, it all collapsed at the last minute when I visited Well-Read Books of Wigtown. This was my downfall, my predestined sciatica. It is a beautifully curated shop, and the first hints of books on witchcraft created the sulphurous smell of trouble. The book of spell-casting cast its spell.

Before I knew it, I had found Stanislav Grof’s Books of the Dead: Manuals for Living and Dying, and next to that was a book about The Tree of Life. The shop is run by a former QC. Unfortunately, when I got to the till I said, ‘I don’t suppose you have any more in this series?’ and a vast pile thudded onto the counter.

I bought one on Robert Fludd and Earth Magic by John Michell (author of The View Over Atlantis). I decided I didn’t need any more and had a cup of tea and a cake. But that gave me time to think and made me realize that I did need some more, goddammit! What do they put in those cakes? Or was it the tea?

For my book event that evening I was interviewed by Lee Randall, an expert inquisitor. The last time she interviewed me in Wigtown something peculiar happened. In my book I’m a Joke and So Are You I had written about a car crash that I was in shortly before my third birthday. My mother was severely injured. Being nearly three, I thought I must have caused it. Lee asked me about the accident, and some long-hidden emotion – muffled and kept under wraps for decades by an intense Englishness – suddenly made itself known and I burst into tears live onstage. I don’t think Lee had ever experienced such a spectacle before. I regained my composure quite quickly, but my mind, with a maturity that was rare for it, said to me, ‘Don’t get out of this with a joke. Don’t make fun of this. It was real, and turning it into shtick belittles what just happened.’ Then we moved on.

This time, though, we talked about spaceflight and the block universe, and there were no deeply hidden emotions to take me, or Lee, by surprise. At the signing table I sat behind Perspex while people in masks told me their names and I said, ‘Sorry, Corinna?… Colin?… Coriolanus?… Ah, Kenny… NO! Kerry.’ The dedications with the most crossing-outs are worth the most: honest.

Laugharne

I sneak my Wigtown book bags back into the house while my wife is at work – nothing to see here. In the past I have nipped home with some bags of books, only to find that she’d come back early and so I had to secrete them under the shed. I’d come in empty-handed and whistling, a jaunty tune being the clear signifier of a terrible ‘five hardbacks, a large-format art book and seven Penguin Modern Classics’ guilt.

I am out of the door again for the journey to Laugharne before my presence is noted. She’ll simply think the books have been breeding again.

Laugharne is one of my favourite festival destinations. If you have read Under Milk Wood you’ll know that this is where Dylan Thomas built Llareggub. It is a festival of fascinating people, just far enough away from London that the more pompous elements of media society cannot be bothered or don’t know it exists. Its isolation serves to weed out the incurious who, at the first mention of changing trains at Swansea, remember they are doing something terribly exciting in the Cotswolds that weekend.

It’s the Brigadoon of arts festivals. Guests have included Patti Smith, Ray Davies, Peggy Seeger, Linton Kwesi Johnson and Jackie Morris. On one visit I spent the night having a fireside chat with the artist Peter Blake about our shared love of masked wrestlers. The air smelt of toasted marshmallows as he told me stories about Kendo Nagasaki. Memories like these can jolt me out any melancholia.

When I contemplate the mercurial rise of some with whom I have shared stages, and who now spend their days wondering which helicopter will go best with their loafers, I remind myself that my strange career has led to moments when I’ve talked to world-famous artists about piledrivers.*

Laugharne is also temporary home to one of my favourite bookshops, Dylans, a mobile library turned into a mobile bookshop by Jeff Towns, passionate bookseller and collector for more than fifty years. He is a man full of tales and knowledge, and what he doesn’t know about Kendo Nagasaki, he makes up for with stories about Ted Hughes and Oliver Sacks.

The day before the festival some of us gather together for a meal. I am seated opposite the poet and hugely successful TV producer, Henry Normal. I have recently taken to performing poetry, and Henry has recently returned to being a full-time poet. It seems that we were both struck by the same poet in our youth: not Keats or Yeats or Rossetti, but Spike Milligan, particularly his Small Dreams of a Scorpion, a thin volume of his more serious thoughts on human folly.

The forecast for the weekend is perpetual rain. This is a perfect location for couples in lovingly maintained Citroën 2CVs to pull over in the hope of a walk, but then get no further than looking at the view through the windscreen wipers. They will sip from a Thermos of oxtail soup, brushing fallen pickle off their sou’westers. This morning, though, it is sunny and I take the opportunity to go on the Dylan Thomas birthday walk. As I walk up the hill, I meet Henry coming down. We are both walking with pencils in hand. Further up, I divert from the birthday walk and take an overgrown path where the blackberry-pickers don’t go. The berries are many and are either dried up or mushy and mouldy, so I think of Seamus Heaney and his blackberry-picking.

But when the bath was filled we found a fur,

A rat-grey fungus, glutting on our cache.

The juice was stinking too. Once off the bush

The fruit fermented, the sweet flesh would turn sour.

By the time I had finished mourning the blackberries, Jeff had set up his bookstall. Sadly, Dylans book bus is no more. It had been barely clinging on to its MOT for some years, and 2020 saw it fail for the final time. It should be buried like an elephant, and all of the book buses should make pilgrimages to see the final lending graveyard.

I walk away from his shelves with a handful of good, hard science – Flying Saucers and Commonsense and a 1936 volume from the Occult Book Society on Practical Time Travel. Hopefully I will tell you more about practical time travel last week. My Ufologist friend Dallas Campbell is particularly envious of my copy of Flying Saucers and Commonsense, as all subsequent reprints became Flying Saucers and Common Sense (you see, you thought it was my